9 The Uveal Tract

NORMAL ANATOMY

THE CILIARY BODY

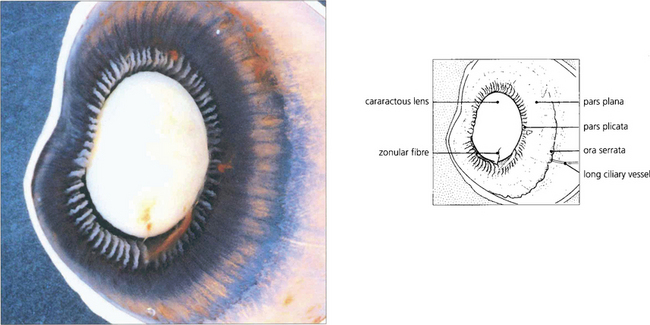

A precise knowledge of the position of the ciliary body is important in the positioning of surgical incisions for vitreous surgery. The surface markings of the ciliary body from the corneal limbus are 1.5–8 mm on the temporal side and 1.5–7 mm on the nasal side. The anterior third (2 mm) contains the ciliary muscle and ciliary processes, and is known as the pars plicata. The posterior two-thirds—the pars plana—extends posteriorly to the ora serrata where it merges with the retina. There is a dense attachment of the vitreous base over this area and on to the anterior equatorial retina (see Ch. 12).

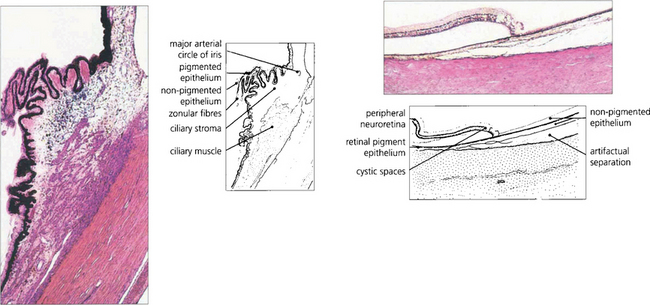

Overlying the ciliary muscle the epithelium and stroma are thrown up into about 80 ciliary processes. These have a vascular stroma and are covered by two layers of epithelium which are continuous with the iris pigment epithelium anteriorly and with the retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina posteriorly. The inner or superficial epithelial layer is nonpigmented and has tight intercellular junctions. Aqueous is secreted through these cells (see Ch. 7). As in the choroid, the capillaries in the ciliary processes are fenestrated.

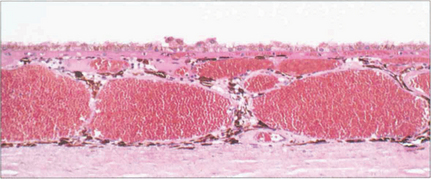

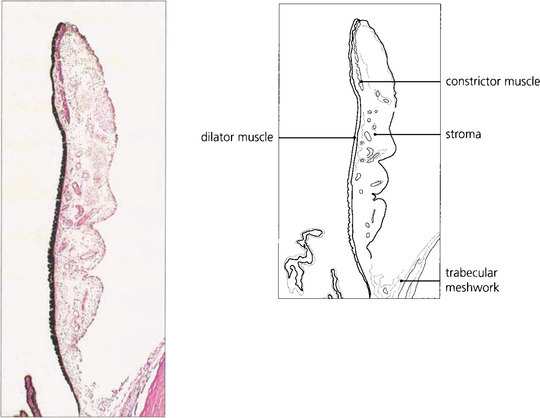

Fig. 9.1 The iris consists of loose, pigmented vascularized tissue anteriorly and a double layer of pigment epithelium posteriorly. The sphincter muscle lies towards the pupillary margin and the dilator muscle in close relation to the pigment epithelium. About 1–2 mm from the pupillary margin on the anterior surface there is a frill known as the collarette. This is the site of the embryological pupillary membrane which atrophies in the eighth month of gestation, and of the minor arterial circle of the iris.

Fig. 9.2 A posterior view of the lens and anterior segment shows the insertion of the retina into the pars plana at the ora serrata and the ciliary processes of the pars plicata. A few remaining zonular fibres can be seen supporting the cataractous lens.

Fig. 9.3 The ciliary body extends from the scleral spur to the ora serrata. Under higher magnification the details of the pars plicata are seen more clearly. Note the two layers of ciliary epithelium, the zonular fibres and the major arterial circle of the iris. At the ora serrata, the neurosensory retina becomes attenuated and cystic, and terminates as the inner non-pigmented epithelium of the ciliary body. The retinal pigment epithelium is continued as the outer pigmented epithelial layer of the pars plana.

BLOOD SUPPLY OF THE UVEAL TRACT

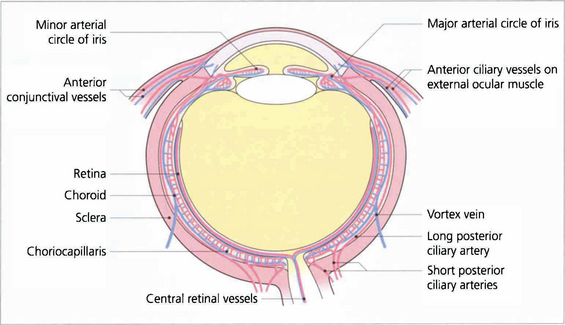

The vascular supply of the uveal tract comes from the posterior ciliary circulation anastomosing anteriorly with the anterior ciliary arteries. The short posterior ciliary arteries leave the ophthalmic artery posteriorly in the orbit (see Ch. 20) and run forwards to penetrate the sclera circumferentially around the optic disc, usually in two major horizontal trunks that divide to supply the optic disc, retrobulbar optic nerve (see Ch. 17) and the choroid. At the disc, two long posterior ciliary branches from these run forward medially and laterally in the lamina suprachoroidia to anastomose with the anterior ciliary arteries adjacent to the major circle of the iris. These long posterior ciliary arteries can frequently be seen in the horizontal meridians of a normal eye if the retinal pigmentation is not too dense. The anterior ciliary arteries are also derived from the ophthalmic artery. They lie on the external ocular muscles (two arteries on the medial, inferior and superior recti, and one on the lateral) and penetrate the sclera at the muscle insertions, and may contribute to the supply of the iris, ciliary body and anterior choroid (although under normal circumstances in a healthy eye the flow is retrograde). The choroidal venous return drains into the orbital veins by the vortex veins, of which there is usually one, but sometimes two, lying in each quadrant of the sclera at the equator.

Fig. 9.5 Diagram showing the vascular supply of the choroid by the anterior and posterior ciliary circulations. (Further details of the anterior ciliary and conjunctival circulations are described in Chapter 5 and the optioc disc in Chapter 17.)

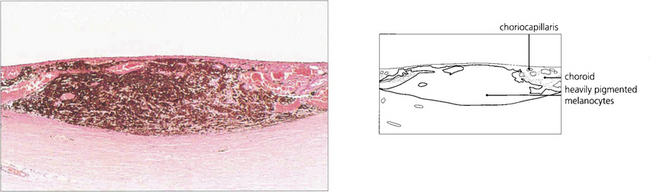

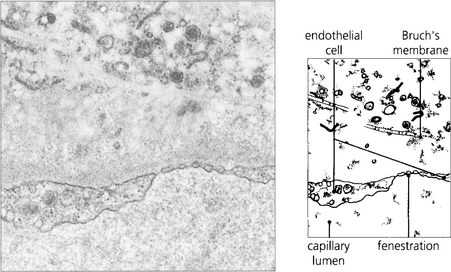

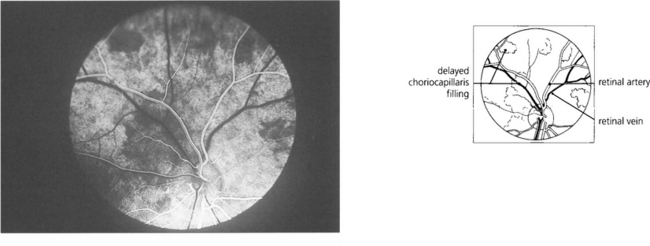

Fig. 9.6 The choroidal arteries divide rapidly to form the choriocapillaris lying beneath Bruch’s membrane. These capillaries have fenestrations between the endothelial cells allowing plasma to leak into the extracellular space. Although there are anatomical anastomoses between the choroidal vessels, physiologically the choriocapillaris functions on a lobular basis.

Fig. 9.7 Clinically this is demonstrated in the earliest phases of a fluorescein angiogram as patchy delayed filling of the choroidal bed, and is seen as choroidal infarcts such as Elschnig’s spots or Siegrist streaks (see Ch. 14).

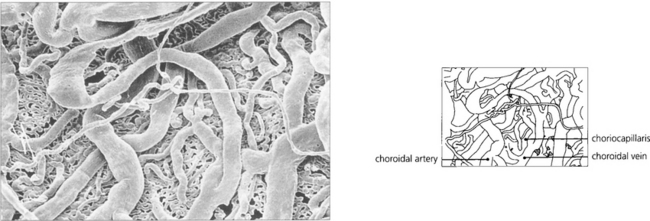

Fig. 9.8 A digest preparation of a cast viewed from the choroidal side in the vicinity of the optic disc shows choroidal arteries supplying the choriocapillaris and drained by the choroidal veins.

By courtesy of Miss J Olver.

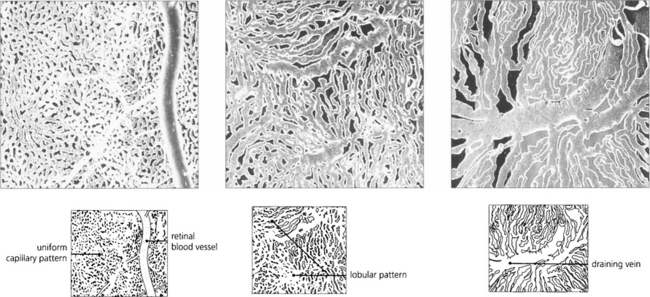

Fig. 9.9 These digest casts of the human choroid show the choriocapillaris from the retinal aspect. At the posterior pole the pattern is uniform (left), in the equatorial fundus a lobular pattern is more apparent (middle), and in the periphery large fan-shaped lobules can be seen (right).

By courtesy of Miss J Olver.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE UVEAL TRACT

COLOBOMAS

Colobomas result from defects of closure of the optic cup that occur at 7–8 weeks of fetal life. They can present as a sectorial deficiency varying from the trivial to the gross. They are typically found inferonasally and may involve the iris, choroid and retina, or optic disc (see Ch. 17).

Fig. 9.10 Iris colobomas are sometimes associated with segmental absence of the lens zonules causing a localized indentation of the lens and usually with defects in the choroid and retina. This child with bilateral iris colobomata also has a poorly sighted divergent left eye due to a large chorioretinal coloboma involving the macula.

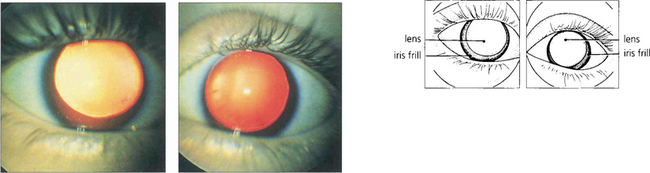

ANIRIDIA

Aniridia occurs either as a familial autosomal dominant disease or sporadically. The autosomal dominant condition is associated with glaucoma, nystagmus, corneal opacities and photophobia, whereas sporadic cases usually have a high incidence of nephroblastoma (Wilm’s tumour). This is associated with deletion of a tumour suppressor gene, which has been identified on chromosome 11, analogous to the retinoblastoma gene on chromosome 13. All such children require regular screening by renal ultrasonography. A vestigial iris remnant can usually be seen as a frill on gonioscopy (see Ch. 7).

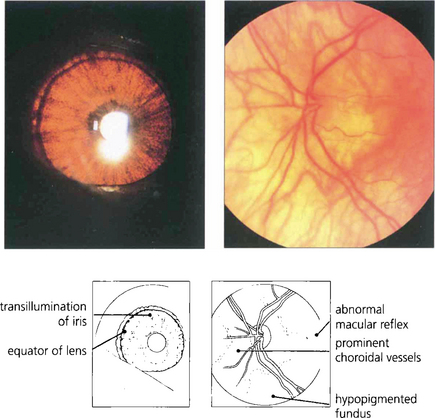

ALBINISM

Apart from increased iris transillumination and hypopigmented fundi, albinos with ocular involvement have congenital nystagmus, macular hypoplasia, a high incidence of squint and amblyopia, and an anomaly of the chiasm in which the majority of optic nerve fibres from each eye decussate. This is thought to be caused by the absence of pigmented cells in the chiasm during embryogenesis; these cells ‘direct’ the ingrowing axons. Ocular albinism is a common cause of congenital nystagmus and it is important to examine all such patients for increased iris translucency by iris retroillumination. Excessive pigmentation (melanosis oculi) is discussed in Chapter 3.

IRIS TUMOURS

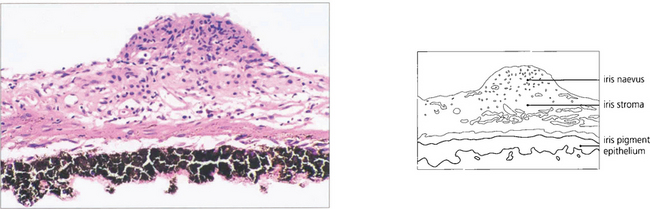

Fig. 9.14 Iris naevi may be pigmented or amelanotic, vascular or avascular and bulky or flat. They may be associated with adjacent ectropion uveae (which is not a sign of malignancy) and can extend into the angle. Iris freckles do not distort normal iris anatomy. Naevi may enlarge or become more deeply pigmented after puberty. Iris naevi can be confused with the so-called iris–naevus (Cogan–Reese) syndrome, a variant of the iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome (see Chs 6 and 8).

Fig. 9.15 The naevus is formed by proliferation of iris melanocytes which form a nodular layer on the anterior surface of the stroma.

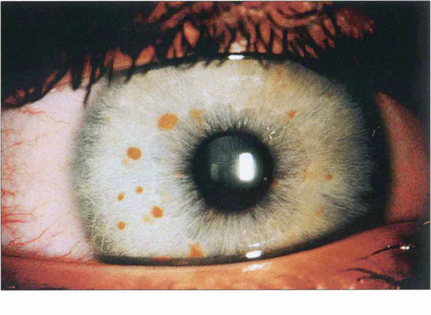

Fig. 9.16 About 90 per cent of patients with neurofibromatosis develop multiple hamartomatous naevi (Lisch nodules) on the stromal surface by their teens. These can occur in both neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2, although they are more common in type 1 (see Chs 2 and 20).

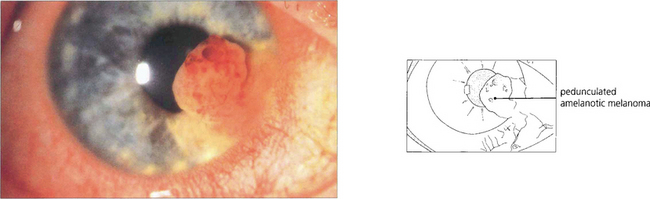

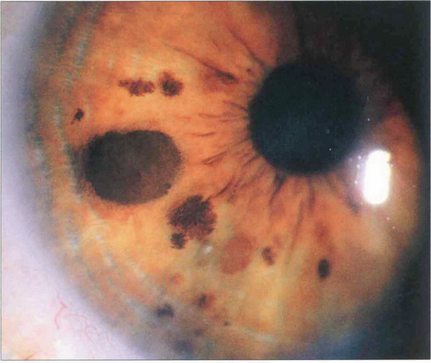

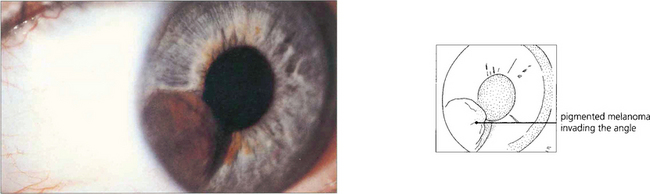

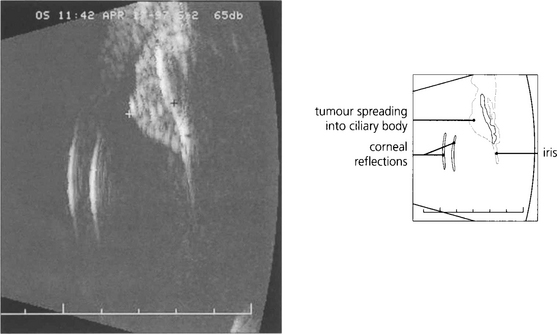

Fig. 9.17 Melanomas of the iris may be clinically indistinguishable from naevi until growth can be demonstrated. Almost all are located in the inferior iris. Colour photography is helpful to document the lesion. Fluorescein angiography is unhelpful in determining whether the tumour is benign or malignant. Some melanomas are highly vascular and may mimic haemangiomas. If the tumour extends to the angle, transpupillary transillumination may reveal ciliary body involvement although high-frequency ultrasound scanning is more accurate. In some centres, local resection has been replaced by radiotherapy delivered with either an iodine plaque or proton beam. Although iris melanomas have a relatively good prognosis compared with more posterior melanomas they should not be considered benign.

Fig. 9.19 High-frequency ultrasound imaging is extremely useful in delineating the extent of the lesion and documenting its size.

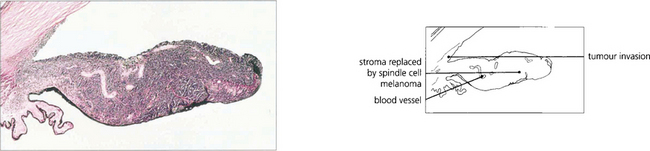

Fig. 9.20 This iris is diffusely infiltrated by a low-grade spindle cell melanoma with extension on to the inner surface of the trabecular meshwork.

By courtesy of Professor W R Lee.

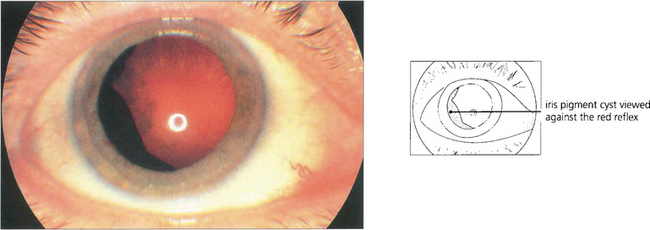

Fig. 9.21 Cysts can arise from the posterior surface of the iris or ciliary body and may mimic a melanoma. If the edge of the cyst is not visible at the pupil margin it can often be seen with a three-mirror lens after maximal mydriasis. High-frequency ultrasound scanning is very useful to demonstrate the cystic nature of the lesion, its site and extent. Clear cysts arise from the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium, whereas pigmented cysts originate from the iris pigment epithelium; these cysts may wobble on eye movement and are often multiple and bilateral. They tend to cause cataract and may result in glaucoma. Rarely, implantation cysts lined by stratified squamous epithelium occur within the iris stoma.

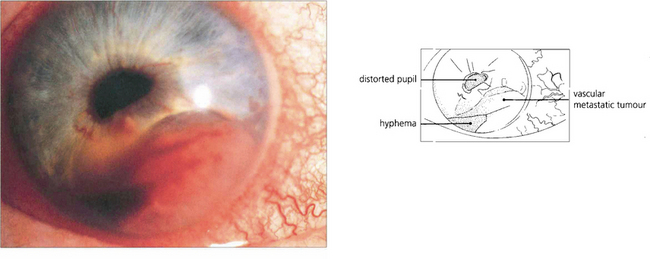

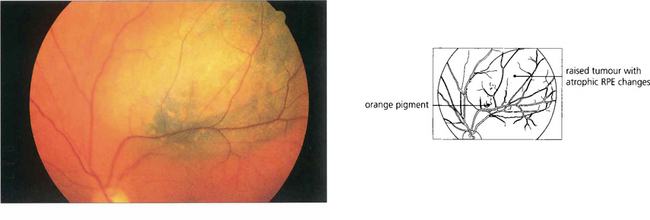

Fig. 9.22 Metastases to the iris are rare. They present as white or pink tumours that grow rapidly, becoming irregular and haemorrhagic. Most arise from primary neoplasms in lung or breast.

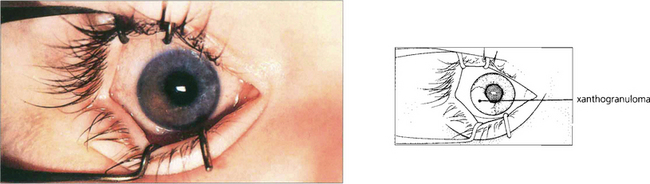

Fig. 9.23 Juvenile xanthogranuloma has similarities to but is separate from the spectrum of Langerhan’s histiocytic cell proliferative disease. Iris lesions are rare, affecting children under 3 years of age who also develop typical orange skin lesions. Infants present with a unilateral, raised, yellowish lesion on the iris with spontaneous hyphema. Vision may be lost from secondary glaucoma. Histological examination shows a histiocytic infiltration of the iris that responds to steroids or radiotherapy.

By courtesy of Mr J J Kanski.

CHOROIDAL AND CILIARY MELANOTIC TUMOURS

CHOROIDAL NAEVI

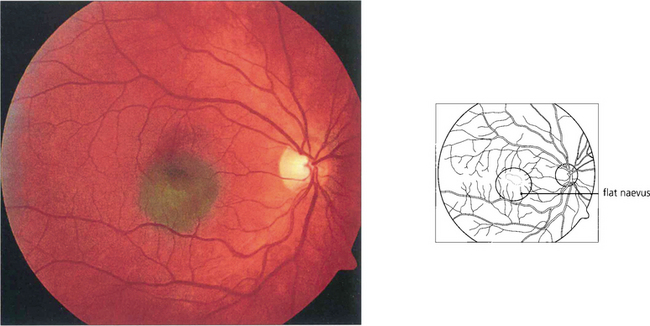

Fig. 9.24 Choroidal naevi occur in about 10–30 per cent of the Caucasian population and are usually detected after puberty. Most naevi are small and flat with a slate-grey colour and the overlying retinal pigment epithelium shows minimal secondary change.

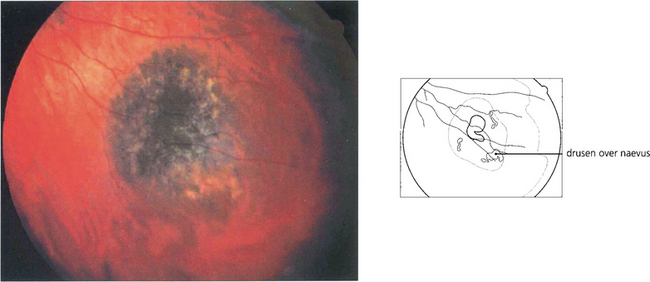

Fig. 9.25 A small proportion of choroidal naevi are relatively bulky and therefore induce degenerative changes in the overlying retinal pigment epithelium, similar to those caused by melanomas. Clinical features indicative of a benign nature are a tumour thickness of less than 2 mm, the presence of hard drusen on the surface, the absence of clumps of ‘orange pigment’, and the absence of a serous retinal detachment over the tumour. Such signs are not reliable indicators, however, and suspicious naevi should be monitored for growth comparing the ophthalmoscopic appearances with a baseline colour photograph. The patient should be seen after 3–4 months and then 6 monthly and eventually once a year. Such monitoring should be lifelong because malignant growth can occur after many years of apparent inactivity.

CHOROIDAL MALIGNANT MELANOMA

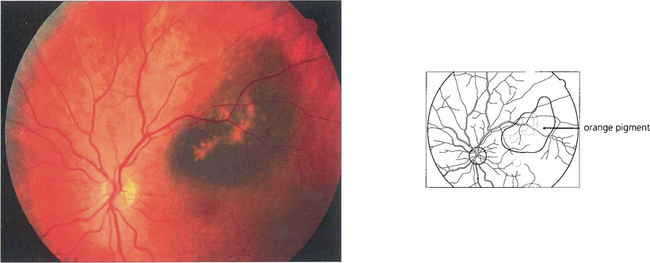

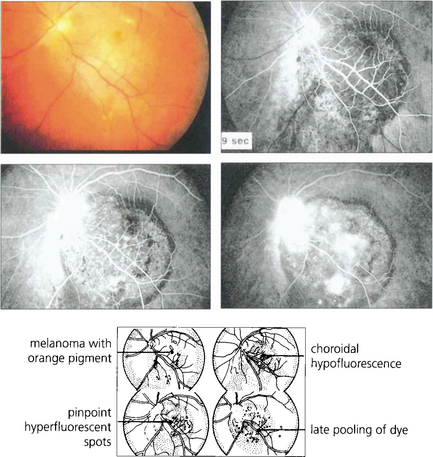

Fig. 9.27 Ophthalmoscopically, abnormal deposits of lipofuscin accumulate over the surface of the tumour (‘orange pigment’).

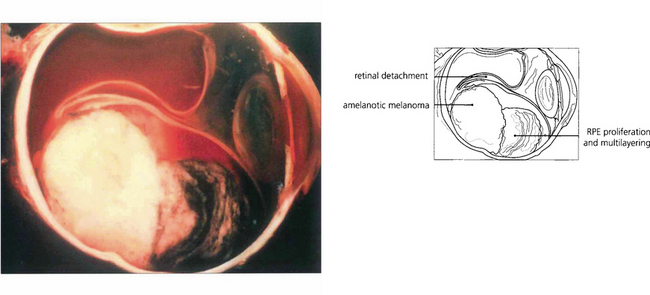

Fig. 9.28 This patient has a large malignant choroidal melanoma that has not broken through Bruch’s membrane.

Fig. 9.29 The degree of pigmentation in uveal melanomas varies greatly even within the same tumour, but this cannot always be properly appreciated clinically unless the overlying retinal pigment epithelium is atrophic or absent. Melanomas may have tapering margins where the overlying retinal pigment epithelium is still relatively healthy; therefore, unless the tumour is deeply pigmented, such lateral extentions may be clinically invisible.

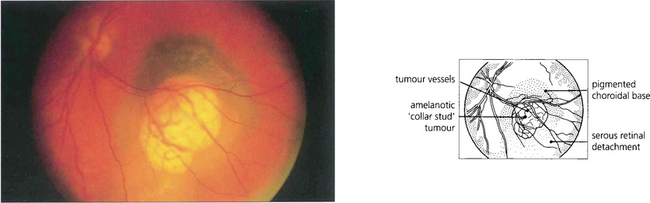

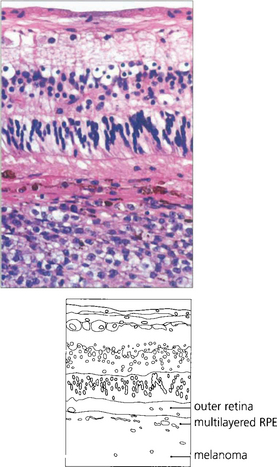

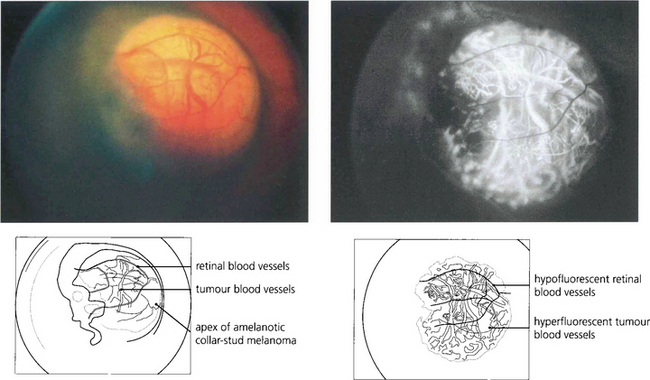

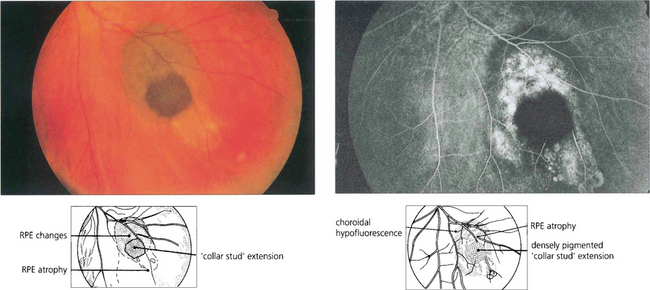

Fig. 9.30 This is an amelanotic collar-stud melanoma with engorged tumour blood vessels. These are usually visible ophthalmoscopically only if the tumour has ruptured the retinal pigment epithelium and is nonpigmented. The pigmented base of this collar stud tumour is due to multilayering of the retinal pigment epithelium and not to melanin in the tumour.

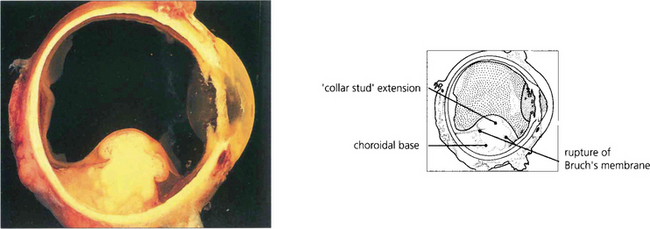

Fig. 9.31 Choroidal melanomas are moulded into a smooth dome by the overlying Bruch’s membrane and retinal pigment epithelium. When the tumour ruptures these layers it herniates into the subretinal space. The edge of the break in Bruch’s membrane strangulates the blood vessels in the prolapsed part of the tumour so that they become engorged, also leaking fluid. The herniated part of the tumour becomes globular so that the melanoma develops a mushroom shape (also described as ‘collar-stud’ or ‘dumb-bell’).

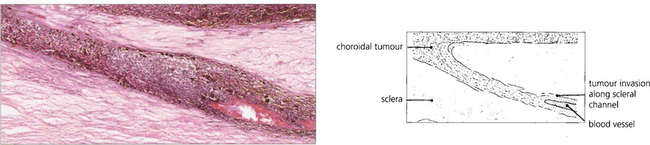

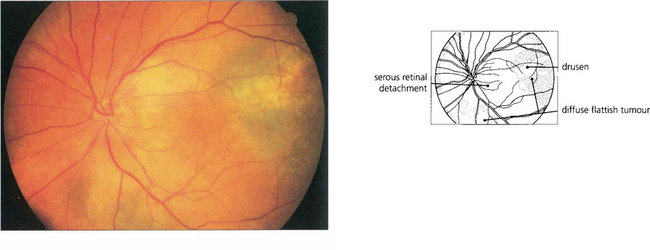

Fig. 9.32 A small proportion of choroidal melanomas infiltrate the uvea without forming a bulky tumour. Such ‘diffuse’ melanomas tend to be highly aggressive and have often extended extraocularly by the time they are diagnosed.

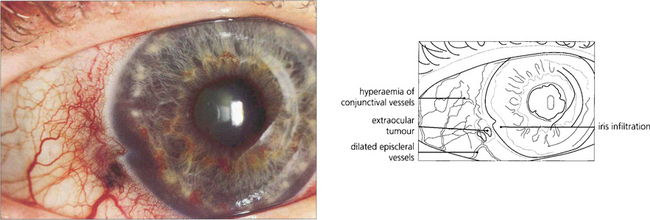

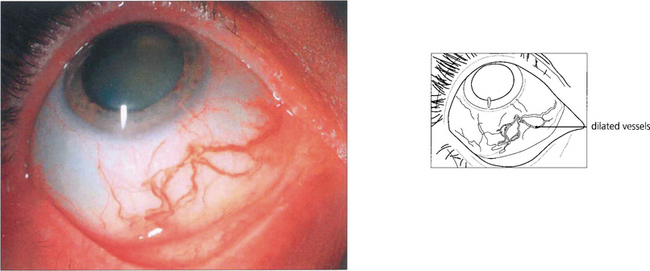

Fig. 9.33 The episcleral blood vessels overlying a large ciliary body tumour tend to become dilated and tortuous and may be mistaken for episcleritis. Such ‘sentinel vessels’ can occur with benign tumours and are not necessarily a sign of malignancy.

Fig. 9.34 Choroidal melanomas, and indeed other tumours, tend to cause secondary degenerative changes in the overlying tissues that influence their ophthalmoscopic features. The choriocapillaris is eventually totally destroyed. The retinal pigment epithelium becomes multilayered in some areas and atrophic in others, and multiple small pigment epithelial detachments may develop over the tumour.

Fig. 9.35 If the retinal pigment epithelium is still present over a melanoma, drusen and small pigment epithelial detachments will appear as hyperfluorescent spots. When fluorescein diffuses from the residual choriocapillaris and tumour vessels through defects in the retinal pigment epithelium, there is diffuse late hyper-fluorescence as the dye accumulates in the subretinal space. In comparison to fluorescein angiography, indocyanine green angiography provides more information about tumour extent and vascularity deep to the retinal pigment epithelium.

Fig. 9.36 If the melanoma is exposed to view because Bruch’s membrane is ruptured or the retinal pigment epithelium is absent or atrophic, the angiographic appearances depend on the degree of pigmentation. An amelanotic collar-stud tumour is hyperfluorescent and large choroidal vessels are visible near its surface.

Fig. 9.37 This deeply pigmented collar-stud melanoma has broken through retina as well as Bruch’s membrane and retinal pigment epithelium. The angiogram shows how the tumour itself is totally nonfluorescent. The surrounding hyperfluorescence arises from drusen and subretinal fluid over abnormal retinal pigment epithelium anterior to the tumour and from the sclera where the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid are atrophic.

Reproduced with permission of Eye.

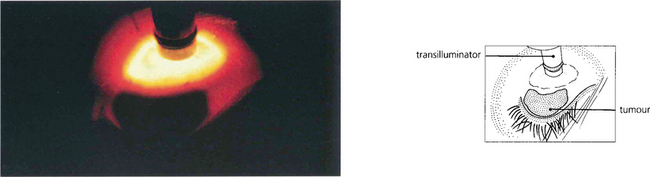

Fig. 9.38 Transpupillary transillumination will help to distinguish pigmented from nonpigmented tumours. Not all pigmented tumours are melanomas, however, and conversely not all melanomas are pigmented. Transpupillary transillumination gives an approximate indication of the extent of a pigmented tumour. Care must be taken not to be misled by oblique illumination of the tumour or by an adjacent subretinal haematoma.

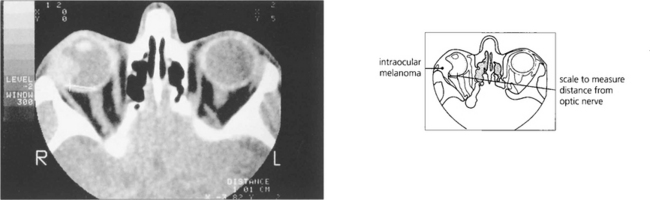

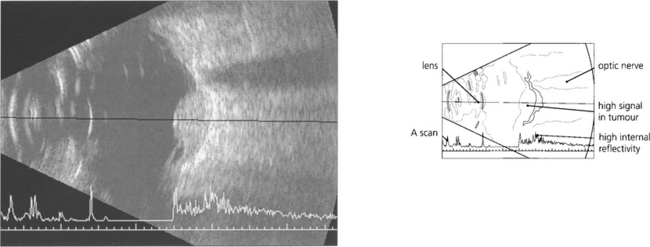

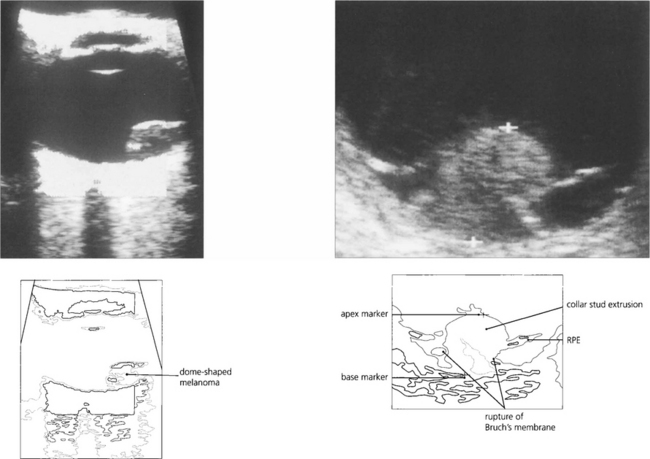

Fig. 9.39 When making a diagnosis or planning therapy, A and B scan ultrasonography (see Ch. 1) are essential for measuring the dimensions and defining the extent of the tumour. Ultrasonography can help to identify extraocular extension before surgery and to confirm or exclude the presence of a tumour when the ocular media are opaque. Melanomas tend to have a highly reflective surface with a low internal acoustic reflectivity; this helps to distinguish them from haemangiomas and secondary neoplasms which have high reflectivity. Rare nonmelanomatous uveal tumours such as leiomyoma can be indistinguishable from melanoma. A collar-stud configuration is almost pathognomonic of melanoma.

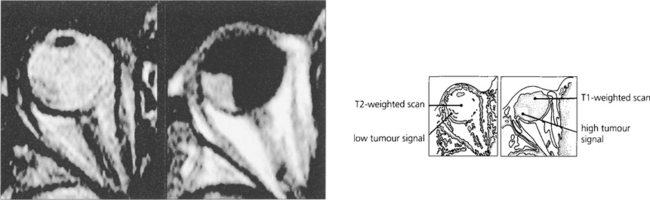

Fig. 9.40 Melanin has short T1 and T2 relaxation times so that T1-weighted images are relatively hyperintense and T2-weighted images are hypointense compared with vitreous on MRI. These characteristic paramagnetic features may be helpful in distinguishing melanoma from other conditions (e.g. metastasis, haemangioma and haematoma). It must be remembered, however, that other tumours (e.g. melanocytomas, adenocarcinomas and leiomyomas) can contain melanin which may confuse the result.

By courtesy of Dr Nigel McMillan.

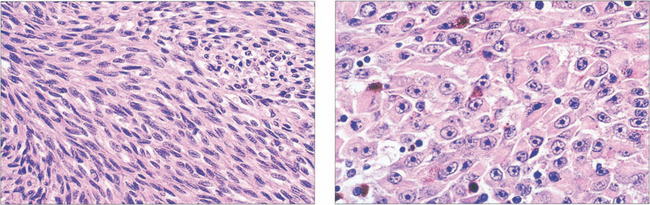

PATHOLOGY OF CHOROIDAL MALIGNANT MELANOMAS

Fig. 9.42 Spindle cells (left) are fusiform with indistinct cell membranes and are arranged in tight bundles. The nuclei vary from slender to plump; nucleoli may or may not be distinct. Epithelioid cells (right) are larger, polyhedral and more pleomorphic with abundant cytoplasm. The cell membranes are distinct and extracellular space often separates cells. Nuclei are large with prominent nucleoli. Mitotic figures are seen more frequently than in spindle cells.

Fig. 9.43 In some tumours spindle cells have a fascicular arrangement. This has no pathological significance.

TREATMENT OF UVEAL MELANOMAS

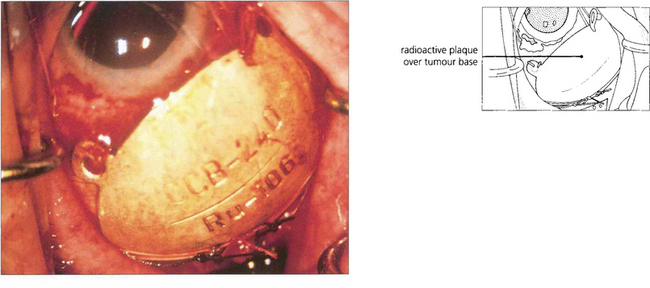

Fig. 9.46 In most specialist centres, brachytherapy using a 106Ru or 125I plaque is the first choice of treatment. Another method of directing radiation at the tumour is by means of a highly collimated beam of heavily charged particles, such as protons, delivered with a cyclotron. The scope of stereotactic radiotherapy is being investigated. Transpupillary thermotherapy, which has superseded photocoagulation, gently raises the tumour temperature to between 45°C and 60°C for about 1 min, by means of a 3-mm diode laser beam. It is usually used in conjunction with radiotherapy (sandwich technique), but in some centres it is administered alone to small tumours located close to the disc or fovea.

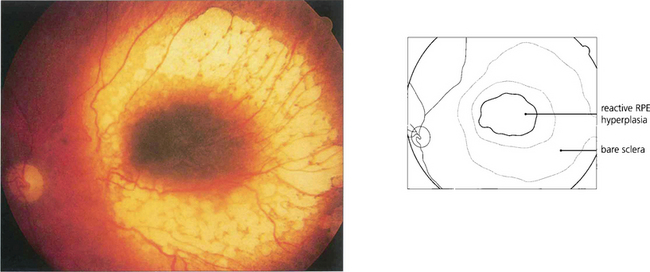

Fig. 9.47 After plaque radiotherapy the tumour gradually flattens over 2–3 years, usually leaving a residual pigmented mass surrounded by choroidal atrophy. As long as there is no tumour regrowth, further treatment is not needed.

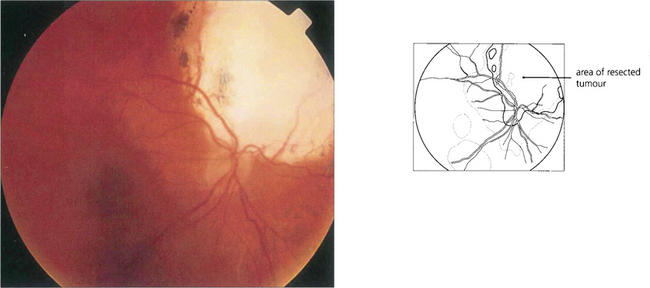

Fig. 9.48 In a few centres tumours considered to be unsuitable for radiotherapy because of their large size or juxtapapillary location can be treated by local resection, performed either trans-sclerally or trans-retinally (i.e. endoresection). With pseudophakic correction, this dressmaker retained visual acuity of 20/15 and her occupation 7 years after endoresection of a juxtapapillary choroidal melanoma in the right eye.

OTHER CHOROIDAL LESIONS

CHOROIDAL METASTASES

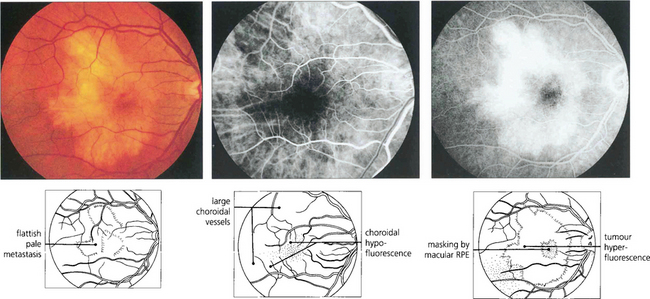

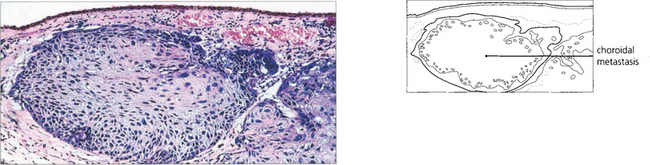

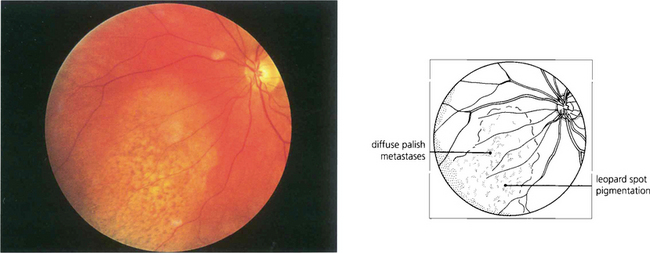

Fig. 9.49 Choroidal metastases are amelanotic and tend to grow rapidly so that the retinal pigment epithelium has little time to develop marked proliferative changes. Such tumours are therefore white or yellow with scattered clumps of residual retinal pigment epithelial cells giving rise to a leopard-spot pattern. They may be bilateral and in a minority of patients multiple lesions occur in one or both eyes.

Fig. 9.50 This patient with an intraocular metastasis had widespread secondaries. Biopsy showed the tumour to be an adenocarcinoma, probably arising from the bronchus.

UVEAL EFFUSION SYNDROME

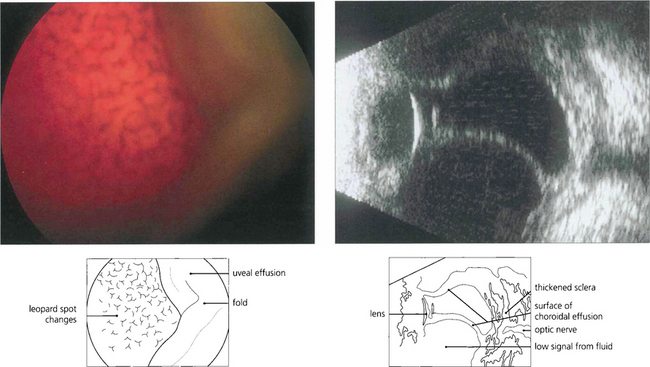

Fig. 9.53 Uveal effusions (see also Ch. 8) may resemble melanoma but are lobulated because of tethering of the choroid to the sclera by vortex veins (left). They tend to occur in the horizontal meridian. Acute effusions can be associated with ocular hypotony. Effusions occur spontaneously as the uveal effusion syndrome in nanophthalmic eyes (axial length <20 mm), in normal-sized eyes with thickened sclera, with posterior scleritis and most commonly as a response to hypotony after intraocular surgery. In the absence of hypotony after recent intraocular surgery the aetiology is thought to be disruption of trans-scleral fluid outflow; if the effusion does not resolve spontaneously these patients respond to a surgical scleral decompression procedure. Leopard-spot pigmentation can be seen over chronic effusions and there may be associated serous retinal detachment. Ultrasonography confirms the absence of solid tumour as shown in this patient with posterior scleritis (right).

Reproduced from Ocular Tumours: Diagnosis and Treatment. Damato: Butterworth Heinemann, 2000.

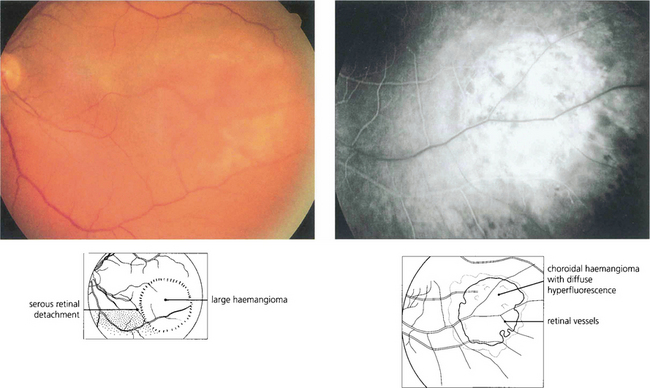

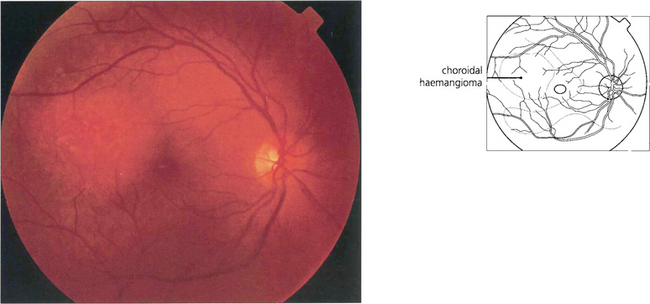

CHOROIDAL HAEMANGIOMA

Choroidal haemangiomas may occur as isolated lesions or as part of the Sturge–Weber syndrome when they may be associated with facial and meningeal angiomas, epilepsy, intellectual impairment and glaucoma from raised episcleral venous pressure (see Ch. 8). In patients with Sturge–Weber syndrome the haemangioma is often flat and diffuse involving the whole fundus, giving it a red ‘tomato ketchup’ appearance. Serous retinal detachment tends to develop over the tumour, extending inferiorly and to the fovea to cause the presenting symptoms. These can become extensive and result in rubeotic glaucoma. Choroidal haemangiomas may bleed during intraocular surgery causing an expulsive choroidal haemorrhage.

Fig. 9.54 This child has the typical facial naevus of the Sturge–Weber syndrome. Ocular involvement is said to be more common when the upper lid is involved by the naevus. Facial hemihypertrophy is a common feature, as in this patient.

With permission from the patient and his family.

Fig. 9.55 These rare tumours usually arise near the posterior pole of the eye as a slightly elevated lesion. They may be discrete and up to several disc diameters in size or diffuse. Both types of haemangioma have indistinct margins and can cause cystic degeneration and serous detachment of the overlying retina. Characteristically, they have the same colour as the adjacent choroid. Haemangiomas usually regress after external-beam or plaque radiotherapy but this approach is being replaced by photodynamic therapy.

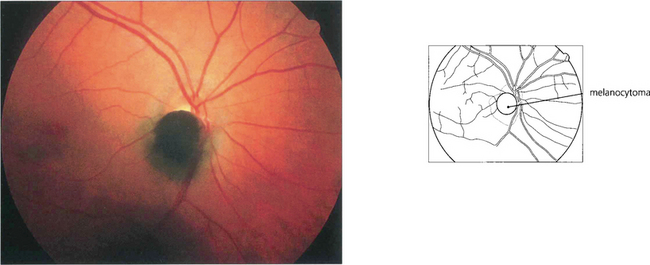

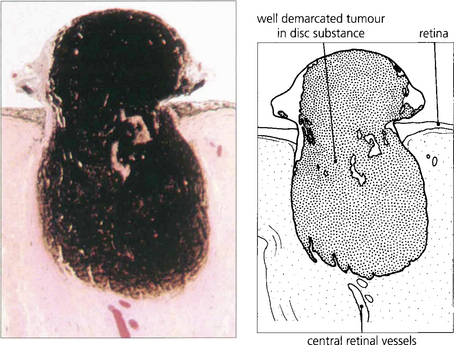

MELANOCYTOMA

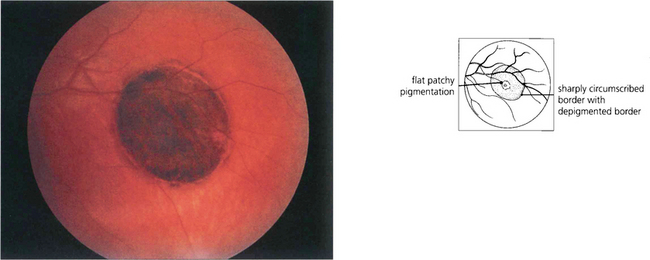

CONGENITAL HYPERPLASIA OF THE RETINAL PIGMENT EPITHELIUM

Congenital hyperplasia of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) is literally a ‘spot diagnosis’. These lesions are flat with a smooth surface that is dark brown or black in colour, and they often have one or more atrophic spots (lacunae), which can predominate. The margins are discrete and may have a hypopigmented border. The lesions may grow gradually over several years and with exceptional rarity may give rise to a nodule, believed to be an adenoma or low-grade adenocarcinoma, which is locally invasive. Multiple small, lightly pigmented and spindle-shaped CHRPE-type lesions may occur in association with familial adenomatous polyposis or Gardner’s syndrome (dominantly inherited polyposis of the colon) (see Ch. 13).

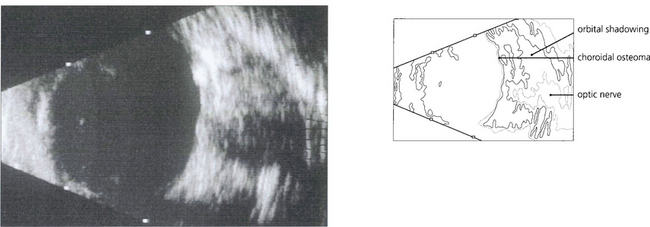

OSSEOUS CHORISTOMA (CHOROIDAL OSTEOMA)

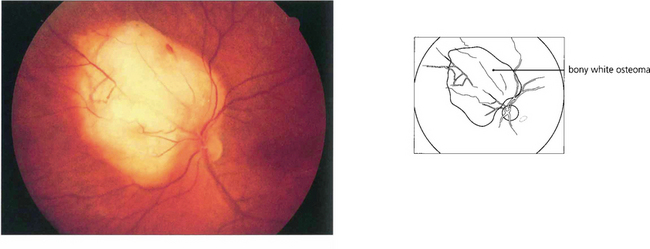

Fig. 9.61 This eye shows a juxtapapillary osseous choristoma adjacent with overlying retinal vascular abnormalities.

COMBINED HAMARTOMA OF THE RETINA AND RETINAL PIGMENT EPITHELIUM

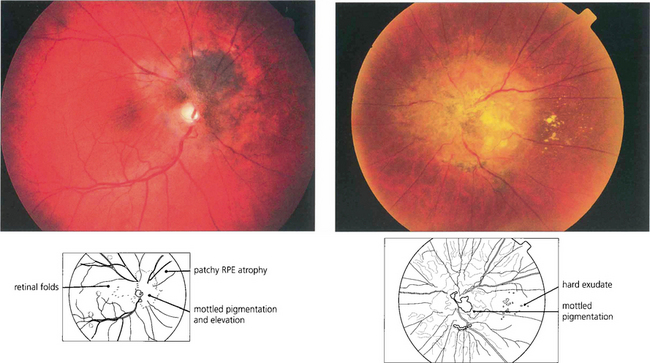

Fig. 9.64 These eyes show a combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium centred on the optic disc with macular traction and retinal vascular abnormalities.

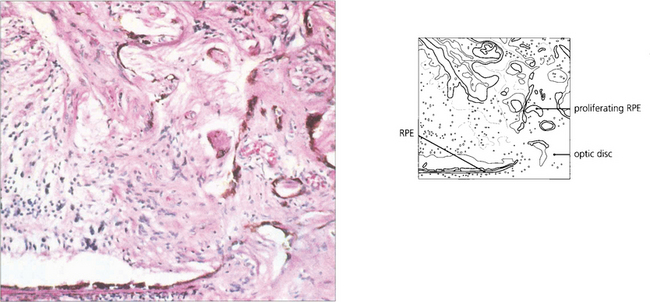

Fig. 9.65 Histological appearance from another patient shows proliferation of the retinal pigment epithelium through the optic disc margin into the retina, with proliferating cells and abnormal vessels.

Reproduced with permission from Yanoff and Fine. Ocular Pathology. Gower Medical Publishing, 1988.

MEDULLOEPITHELIOMA

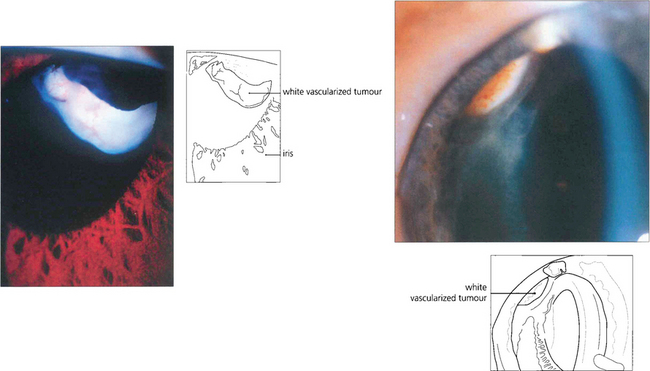

Fig. 9.66 A vascular, pinkish white, ciliary body tumour can be visualized in these children.

Reproduced from Damato B. Ocular Tumours: Diagnosis and Treatment. Butterworth Heinemann, 2000.

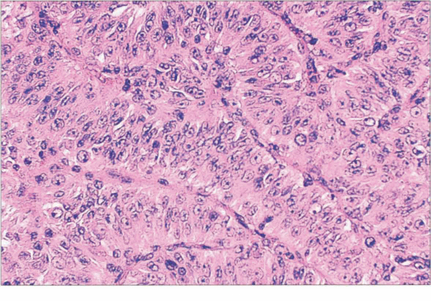

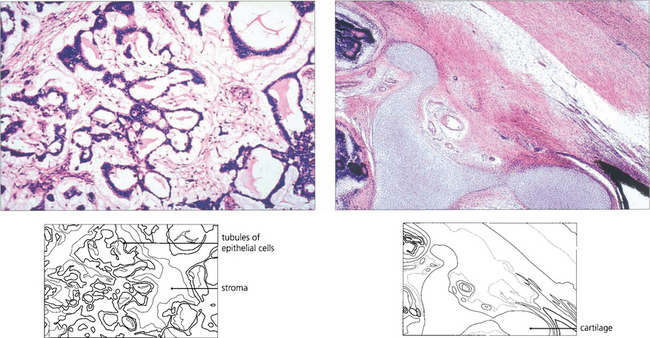

Fig. 9.67 Histologically medulloepitheliomas are of two types: nonteratoid and teratoid. The nonteratoid tumour (left) has a myxoid or fibrous stroma in which proliferating epithelial cells form tubules and acini. In the teratoid type (right) the presence of heterologous elements such as cartilage (as in this case), skeletal muscle or neural tissue can also be found, reflecting the pluripotential nature of the optic cup. Malignancy depends on the degree of differentiation but metastic deaths are rare.

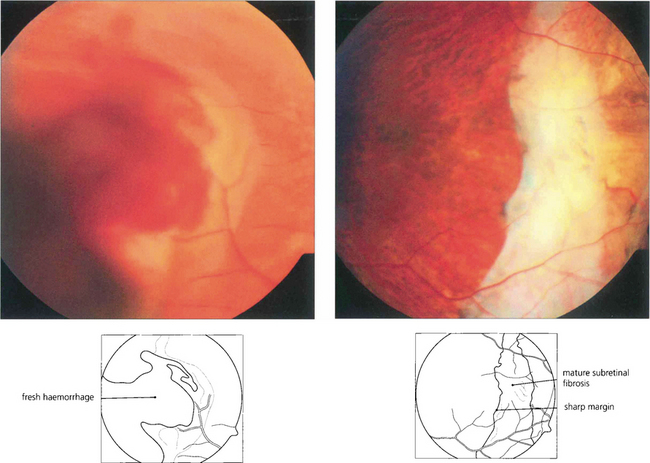

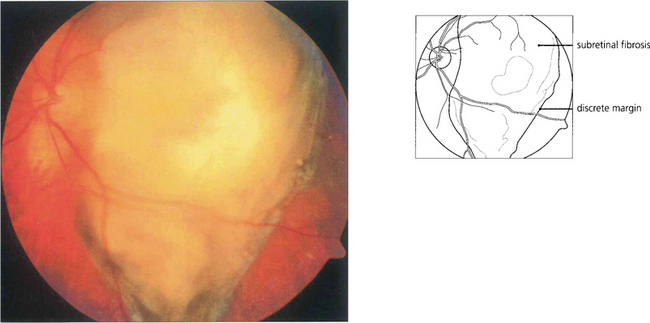

DISCIFORM MACULAR LESIONS IN THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF TUMOURS

Fig. 9.68 Macular disciform lesions can resemble melanoma if they are bulky. Active lesions tend to have subretinal haemorrhage and exudation, signs that are rare with melanoma. Mature disciform lesions have discrete irregular margins, unlike the smooth diffuse margins of melanoma and white subretinal fibrosis. In an elderly patient a macular mass with vitreous hemorrhage is more likely to be a disciform lesion than melanoma. The diagnosis should be established by waiting for the haemorrhage to clear spontaneously or by vitrectomy and observing shrinkage of the lesion. Sequential ultrasonographic scans are likely to show shrinkage with a disciform lesion and growth with a melanoma.