The Use of Skin Grafts with Local Flaps

Pivotal Flaps with Skin Grafts

There are four types of pivotal flaps: rotation, transposition, interpolated, and island.1–3 All pivotal flaps are moved toward the defect by pivoting the flap around a fixed point at the base of the pedicle. Except for island flaps skeletonized to the level of their nutrient vessels, the greater the arc of pivot, the shorter is the effective length of the flap (see discussion in Chapter 6). Thus, pivotal flaps must be carefully designed to accommodate this reduction in length. As the flap turns in an arc around its relatively fixed pivotal point, redundant tissue, known as a standing cutaneous deformity (dog-ear), develops at the base. Similar to the effective length of the flap, there is a positive correlation between the degree of pivoting of the flap and the size of the standing cutaneous deformity that forms. The greater the pivot, the larger the deformity. Thus, increasing the flap’s pivot will change the flap’s shape, shorten its effective length, and deform the flap’s base from development of a standing cutaneous deformity. To limit these restricting factors, a flap’s arc of pivot should not exceed 90° whenever possible. In addition to the development of larger standing cutaneous deformities as a pivotal flap turns on its base, the larger the size of the flap, the larger in surface area is the deformity for a given pivotal arc. For large pivotal flaps, this deformity can be of sufficient size to allow its excision and use as a full-thickness skin graft to assist the resurfacing of a portion of a cutaneous defect.

Pivotal flaps are highly versatile and can be used to repair many types of facial cutaneous defects. Whereas a pure pivotal flap turns in an arc at its base and is not stretched, most pivotal flaps have some component of advancement. Provided the flap is the same size as the defect, it is the advancement that can cause an increase in wound closure tension and distortion of surrounding facial structures. It is in these situations that the addition of a skin graft can be beneficial. The combined use of pivotal flaps and full-thickness skin grafts is usually reserved for repair of very large defects in instances in which the use of a skin graft is necessary to prevent excessive wound closure tension. The other instance in which this combination is used is when there is insufficient skin at the flap donor site to close the secondary defect.

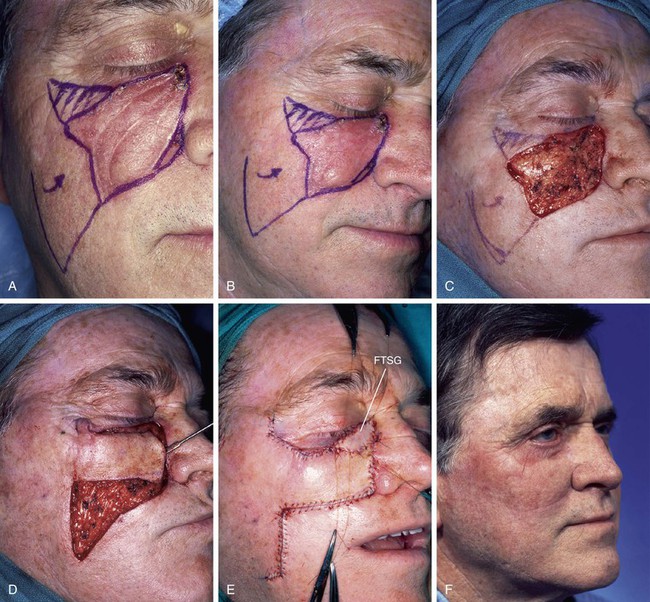

Case 1

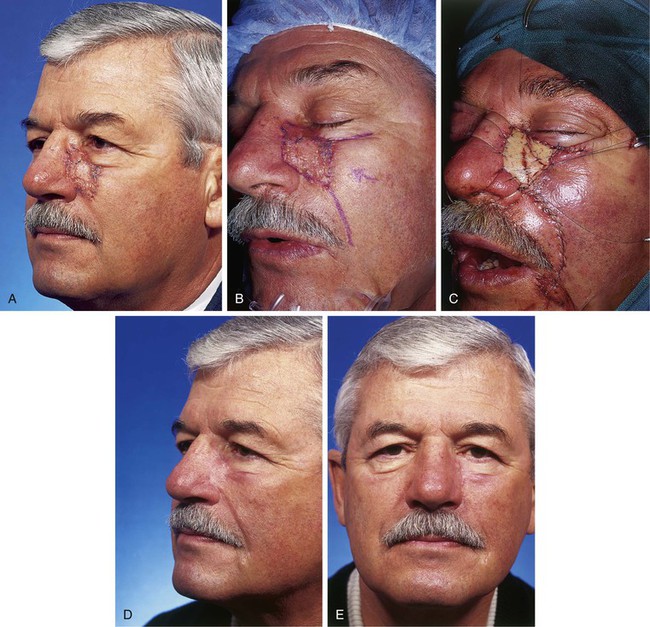

A 52-year-old man presented for excision of atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of the cheek and lower eyelid. This skin abnormality is considered to be at high risk for transitioning to an invasive melanoma. Margins free of disease around the lesion were obtained by the square technique. (See discussion of the square technique in Chapter 8, Case 3.) This resulted in an area requiring resection that measured 4 × 4-cm (Fig. 16-1). The patient’s facial skin was taut and the area of skin excision large relative to the total surface area of the cheek. A rhombic flap was designed for repair of the cheek defect after resection of the lesion. Although the rhombic flap was designed correctly, when the flap was transposed to the recipient site after excision of the skin lesion, excessive wound closure tension was noted. The tension caused a downward pull on the lower eyelid skin, raising concern for retraction or even ectropion of the eyelid. For this reason, a full-thickness skin graft was used to assist with repair. The graft was harvested from the standing cutaneous deformity resulting from pivoting of the flap. The skin graft was positioned between the distal border of the flap and the lower eyelid. This completely relieved wound closure tension, and the wound healed without distorting the eyelid. The proximity of the donor site and the recipient site of the skin graft ensured the best possible skin color and textural match with adjacent facial skin.

FIGURE 16-1 Rhombic flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, Atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia measuring 4 × 4-cm. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. B, Inferiorly based rhombic flap designed for repair after excision of lesion. C, Transposed flap combined with 3.5 × 2-cm full-thickness skin graft. Graft used to prevent downward traction on lower eyelid. Skin graft obtained from standing cutaneous deformity excised at base of flap. D, Postoperative view at 13 months. No revision surgery performed.

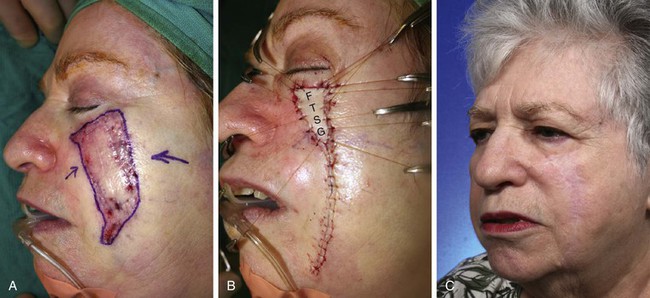

A patient with the same disease as in Case 1 is shown in Figure 16-2. It was necessary to resect a large area of cheek skin in addition to skin of the lower eyelid. In this case, a superiorly based transposition flap was selected for repair to facilitate recruitment of skin for construction of the flap from the jowl area. The jowl region has the greatest skin redundancy of the face. The defect was too large to completely cover with a transposition flap without causing excessive wound closure tension. In this case, such tension was likely to cause lower eyelid retraction or ectropion. To prevent distortion of the lower eyelid, a full-thickness skin graft was used to cover the eyelid component of the defect after resection of the skin lesion. The skin from the standing cutaneous deformity resulting from transfer of the flap (vertical lines of flap marked in Fig. 16-2A) was excised and used as the source for the skin graft. The skin graft served the purpose of reducing overall wound closure tension. It also enabled the use of separate and different skin to reconstruct a defect involving two aesthetic regions of the face, the cheek and eyelid. This in turn facilitated a more distinct topographic separation of the eyelid from the cheek. The skin of the standing cutaneous deformity was non–hair-bearing skin. This skin was also thinner than the skin of the lower face. Both of these qualities made the standing cutaneous deformity of the transposition flap the ideal donor site for the full-thickness skin graft. In this case, the skin graft did not survive completely. As a result, the patient developed a minor ectropion of the lower eyelid. The possible partial or complete failure of the skin graft is one of the disadvantages of combining skin grafts with local flaps to repair facial defects. The other major disadvantage of the combined approach is the possible discrepancy of skin color and texture between flap and graft. However, this is uncommon when the source of the graft is the standing cutaneous deformity formed by the local flap. When skin grafts are harvested from a more distant site, skin color and texture discrepancies are more likely to be observed.

FIGURE 16-2 Transposition flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, B, A 4 × 5-cm lentigo maligna melanoma of cheek and lower eyelid. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. Transposition flap designed for repair of cheek defect after resection of melanoma. Vertical marks indicate anticipated standing cutaneous deformity. C, D, Lesion excised and flap transposed. E, Full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) used to repair lower eyelid component of defect. F, Postoperative view at 3 months. Mild retraction of lower eyelid developed from partial necrosis of skin graft.

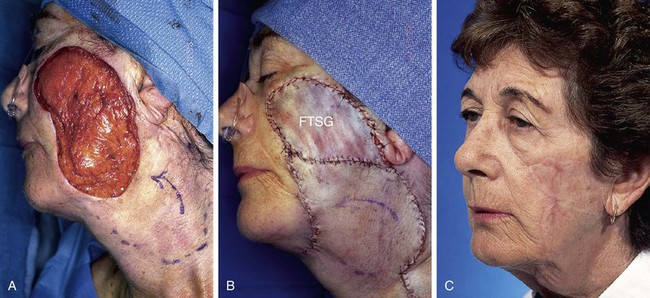

Case 2

The note flap, a transposition flap originally described by Walike and Larrabee,4 allows the closure of a circular defect with a triangular flap. The design of this flap consists of drawing a line tangent to a border of a circular cutaneous defect and parallel to RSTLs for a distance of 1.5 times the defect diameter. A second line the same length as the diameter of the defect is drawn at 50° to 60° to the first line to create a triangle-shaped flap. The final flap design resembles a musical eighth note when it is drawn. The surface area of the flap is typically 75% of the surface area of the defect. Although ideally the flap is used to repair skin defects smaller than 2 cm, larger defects can be closed with this design. The major disadvantage with larger note flaps, as with most large transposition flaps, is that the standing cutaneous deformity is also larger and requires removal. In addition, the major tension vector is perpendicular to the tangential border of the triangular flap, and it is this force that is magnified with larger flaps. (See discussion of note flaps in Chapter 8.)

A 74-year-old woman with a basal cell carcinoma of the right cheek underwent micrographic surgical excision. The resulting skin defect measured 4 × 2.5-cm. A 5 × 1.8-cm laterally based note flap was designed for repair (Fig. 16-3). In retrospect, the flap was not designed sufficiently large enough to close the wound without excessive wound closure tension. This was a particular problem because of the proximity of the defect to the lower eyelid in an elderly patient with lower eyelid laxity. When the flap was transposed, tension caused the lower eyelid to retract from secondary tissue movement. Thus, in addition to the flap, it was elected to use a 2.5 × 1-cm full-thickness skin graft that was placed between the flap and the inferior border of the eyelid. The skin graft was obtained from the standing cutaneous deformity marked in Figure 16-3A. Figure 16-3B shows the patient 5 days after reconstruction and immediately after the removal of a skin graft bolster dressing and sutures. The skin graft healed completely and perfectly matched the skin color and texture of the flap and adjacent facial skin. Most important, however, was the maintenance of a normal lower eyelid position and contour. This case represents an example of selecting an inappropriate local flap to repair a cutaneous defect. It was fortunate that a major complication (ectropion or eyelid retraction) was avoided. Avoidance of the likely complication of eyelid retraction was made possible by use of a full-thickness skin graft to assist the local flap in reconstruction of the defect.

FIGURE 16-3 Transposition flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, A 5 × 1.8-cm laterally based transposition flap designed to close 4 × 2.5-cm skin defect of cheek. Vertical marks indicate anticipated standing cutaneous deformity. B, Five days after transfer of flap combined with 2.5 × 1-cm full-thickness skin graft (FTSG). Graft was used to prevent lower eyelid retraction. C, Postoperative view at 5 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 3

Rotation flaps are pivotal flaps with a curvilinear configuration. They are designed immediately adjacent to the defect and are best used to close triangular defects. In such instances, the triangular defect is covered by a portion of the standing cutaneous deformity, thus facilitating the pivotal movement of the flap and lessening the need to excise the deformity. The greatest wound closure tension of rotation flaps is at the advancing border of the flap. A back cut at the base of the flap shifts the position of the pivotal point and thus changes the wound closure tension vector as well as the location of the standing cutaneous deformity. There are several advantages of rotation flaps. The flap has only two sides; thus it lends itself to placement of one side in a border between aesthetic regions of the face. The flap is broad based, and therefore its vascularity tends to be reliable. There is great flexibility in the design and positioning of the flap. When possible, the flap should be designed so that it is inferiorly based, which promotes lymphatic drainage and minimizes flap edema. Rotation flaps are discussed in detail in Chapter 7.

The patient shown in Figure 16-4 developed a melanoma in situ of the right cheek. Tumor-free margins were obtained around the skin lesion by the square technique. The resulting area requiring excision measured 5 × 3.5-cm. A 7 × 3.5-cm V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flap was designed to reconstruct the cheek after resection of the skin lesion (Fig. 16-4A). The advancement flap proved to be of insufficient size to cover the defect because of the limited superior mobility of the flap. A 3 × 2.5-cm full-thickness skin graft was obtained from the supraclavicular fossa and used to cover the most superior portion of the defect (Fig. 16-4C). Figure 16-4D shows the results of the reconstruction 6 months postoperatively. The skin graft was moderately unsightly, and there was a depressed scar along the lateral border of the transferred flap. For these reasons, a second operation was performed in which incisions were made along the superior and lateral borders of the healed flap. The skin of the flap was widely undermined to develop a cutaneous pedicled advancement flap. The mobilized skin was advanced superomedially. Advancement was such that most of the full-thickness skin graft was removed and the resulting skin defect covered with the advancement flap (Fig. 16-4E). Figure 16-4F-I shows the patient before resection of her melanoma and 7 months after the second-stage surgical procedure.

FIGURE 16-4 V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap and skin graft. A, A 5 × 3.5-cm melanoma in situ marked for excision. B, Melanoma excised. A 7 × 3.5-cm V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flap designed for repair of cutaneous defect. C, V-Y flap in place. A 3 × 2.5-cm full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) used to cover remaining portion of defect. D, Postoperative view at 6 months. Healed FTSG outlined in blue. Horizontal markings represent the superior portion of the V-Y advancement flap. Arrow represents direction of movement of planned cutaneous pedicled advancement flap. E, Advancement flap in place. Majority of FTSG resected and resulting defect covered by advancement flap. F-I, Before excision of melanoma and 7 months after second surgical stage. No revision surgery performed.

Similar to the last case, this case represents an example of poor clinical judgment in designing a local flap. The defect was large, the facial skin was taut, and the flap did not provide sufficient skin to reach the most superior aspect of the defect. A better method for reconstruction of the patient would have been to use a large cervical facial rotation advancement flap. Such a flap may have prevented the need for use of a full-thickness skin graft. However, in repairing very large cutaneous cheek defects with a cervical facial rotation advancement flap, it is not uncommon that the flap must be combined with a skin graft to achieve wound closure.

Cervical Facial Flaps with Skin Grafts

Cervical facial flaps are usually designed as rotation advancement flaps. The cervical facial rotation advancement flap is primarily a rotation (pivotal) flap with a curvilinear configuration. The flap pivots at its base and has one border adjacent to the defect. What distinguishes this flap from a pure rotation flap is that depending on the size and location of the defect, there may be a significant component of flap advancement that increases wound closure tension. Cervical facial rotation advancement flaps are particularly useful for repair of large facial defects when a rotation flap without advancement would cause excessive wound closure tension or distortion of facial features. For very large cutaneous defects, even large cervical facial flaps may not entirely resurface the defect without causing significant distortion of surrounding structures. For these unique cases, a full-thickness skin graft can provide an excellent adjunct to local flap repair.

Case 4

A 71-year-old woman with lentigo maligna melanoma of the left cheek required an extensive resection for complete tumor clearance, resulting in a defect that measured 10 × 7-cm. The defect extended inferiorly from beneath the left lower eyelid to below the angle of the mandible (Fig. 16-5A). Although there was considerable skin redundancy of the patient’s neck, there was insufficient skin to construct a flap that would completely cover the defect. Wide undermining of the cervical skin in the subcutaneous plane was performed to create a large cervical facial advancement flap to assist with repair of the defect. A full-thickness skin graft measuring 9 × 5-cm was harvested from the supraclavicular fossa and used to resurface the superior portion of the defect in the region of greatest wound closure tension (Fig. 16-5B). Figure 16-5C demonstrates the 8-month postoperative result of the reconstruction. The skin graft played an important role in reconstruction of this large facial cutaneous defect that could not be repaired solely with a local flap. Regional and microsurgical flaps are the only alternatives to the method used in this case. These flaps are more complex and would not have provided as good an aesthetic result as the method selected.

FIGURE 16-5 Cervical facial rotation advancement flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, A 10 × 7-cm skin defect of left cheek resulting from removal of lentigo maligna melanoma. An 8 × 7-cm cervical facial rotation advancement flap designed to close inferior portion of defect. B, Transferred flap combined with full-thickness skin graft used to cover superior portion of defect. C, Postoperative view at 8 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 5

A 72-year-old man developed atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of the right cheek. This is considered a pre-melanoma skin condition, and the patient underwent a square technique to identify margins around the lesion that were free of disease. An area of skin involving the cheek and temple measuring 8 × 8-cm required surgical excision (Fig. 16-6). A large cervical facial rotation advancement flap was designed to reconstruct the cheek after resection of the skin lesion. The flap was insufficient to cover the entire defect. A full-thickness skin graft was used to assist the flap in repair of the wound. The graft was harvested from the standing cutaneous deformity created by transfer of the cervical facial flap. The flap and graft survived completely and revision surgery was not necessary. Figure 16-6D shows the results of reconstruction 6 years later.

FIGURE 16-6 Cervical facial rotation advancement flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, B, An 8 × 8-cm area of atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of cheek. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. A 15 × 12-cm cervical facial rotation advancement flap with Z-plasty at base designed to repair cheek after resection. Horizontal lines indicate anticipated standing cutaneous deformity. C, Flap transferred. Bolster dressing is covering full-thickness skin graft harvested from standing cutaneous deformity formed by transfer of flap. D, Postoperative view at 6 years. No revision surgery performed.

Case 6

A 52-year-old woman with basal cell carcinomas of the left temple and left upper lip was referred for wound closure after micrographic surgical excision of the tumors. The lip defect measured 2 × 1.5-cm and was closed with a V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flap. The left temple defect measured 5 × 5-cm (Fig. 16-7A). A large cervical facial rotation advancement flap measuring 15 × 20-cm was designed by marking an incision extending from the temple along a preauricular crease and then posteriorly to the border of the trapezius muscle, where it continued to the inferior neck. The flap was elevated in the subcutaneous tissue plane, pivoted, and advanced to cover approximately 80% of the surface area of the temple defect. A full-thickness skin graft measuring 5 × 2-cm was used to cover the distal portion of the defect (Fig. 16-7B). The graft was obtained by using the redundant skin of the flap that overlapped the earlobe after advancement of the flap. The 4-month postoperative result is demonstrated in Figure 16-7C. The majority of the scars were effectively camouflaged by positioning incisions for the flap along aesthetic boundary lines. Likewise, the skin graft placed adjacent to the temporal hairline was camouflaged by the temporal tuft of hair.

FIGURE 16-7 Cervical facial rotation advancement flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, A 5 × 5-cm left temple skin defect after excision of basal cell carcinoma. A 15 × 20-cm cervical facial rotation advancement flap designed to close defect. B, Flap transferred. A 5 × 2-cm full-thickness skin graft used to cover superior portion of defect. C, Postoperative view at 4 months. No revision surgery performed.

Advancement Flaps with Skin Grafts

Unipedicle cheek advancement flaps typically depend on the relative mobility and elasticity of the skin and soft tissue of the lower face for movement of the flap. Unlike pivotal flaps that generate only one standing cutaneous deformity, unipedicle advancement flaps form two deformities, one on either side of the advancing flap. For large defects of the cheek repaired with an advancement flap that is insufficient to cover the entire defect, the two standing cutaneous deformities formed by skin advancement can be excised and used as full-thickness skin grafts to assist the flap with closure of the defect. This combined approach may prevent distortion of the eyelid or vermilion and in some instances be instrumental in preservation of facial aesthetic borders.

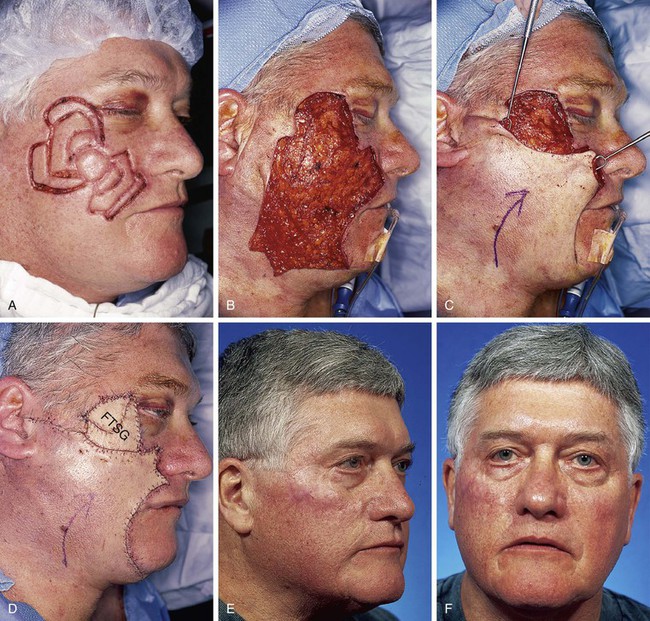

Case 7

A 62-year-old man was diagnosed with atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of the right cheek. A margin free of hyperplasia was established by the square technique (Fig. 16-8A). The patient was referred for resection of the lesion and reconstruction. The skin defect created after the resection measured 8 × 7-cm and extended from above the right lateral canthus to below the level of the right oral commissure (Fig. 16-8B). A 10 × 15-cm unipedicle advancement flap was designed for repair of the defect. The advancement flap was of insufficient size to completely cover the defect (Fig. 16-8C). The two standing cutaneous deformities created by advancement of the flap were excised and used as full-thickness skin grafts to resurface a 5 × 5-cm area of the superior portion of the defect (Fig. 16-8D). The full-thickness skin grafts served the purpose of reducing wound closure tension and preventing distortion of the right ala and lower eyelid. The flap and skin grafts healed without necrosis. However, scar contracture caused mild retraction of the lower eyelid. Scar revision surgery including Z-plasty was necessary to correct the eyelid retraction. This minor revision procedure produced a satisfactory aesthetic result (Fig. 16-8E, F).

FIGURE 16-8 Cheek advancement flap and full-thickness skin grafts. A, Atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of cheek measuring 8 × 7-cm. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. B, Cutaneous defect after excision of lesion. Cheek flap reflected inferiorly. C, A 10 × 15-cm advancement flap mobilized to resurface lower portion of defect. D, Superior portion of defect (5 × 5-cm) covered with two full-thickness skin grafts (FTSG) obtained from excised standing cutaneous deformities resulting from flap advancement. E, F, Postoperative views at 3 years. Scar revisions in form of Z-plasties performed after initial procedure.

Case 8

A 67-year-old man was diagnosed with atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of the left cheek and nasal sidewall. The square technique was used to ensure a tumor-free margin (Fig. 16-9A). The resection necessary to remove the entire lesion extended from the medial cheek onto the nasal sidewall and medial aspect of the lower eyelid. A 5 × 5-cm unipedicle advancement flap was designed to close the cheek component of the defect. The flap design was modified so that the two incisions typically required to create an advancement flap were positioned in facial aesthetic boundaries rather than parallel to each other. In this case, the incisions to create the flap were placed in the melolabial crease and along the infraorbital bony rim (Fig. 16-9B). This flap design enabled the inferior standing cutaneous deformity formed by advancement of the flap to be excised in the melolabial crease to camouflage the scar. To segregate the healing process and to preserve the nasofacial sulcus, the nasal sidewall defect was closed with a 3 × 1.5-cm full-thickness skin graft. The component of the defect involving the lower eyelid was also repaired with a separate full-thickness skin graft. The grafts were obtained from the excised standing cutaneous deformities that formed along the infraorbital bony rim and in the melolabial crease (Fig. 16-9C). The skin grafts served the purpose of relieving wound closure tension and maintaining aesthetic boundaries between facial aesthetic regions.

FIGURE 16-9 Cheek advancement flap and full-thickness skin grafts. A, A 3 × 3-cm lentigo maligna melanoma of nose, cheek, and lower eyelid. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. B, A 5 × 5-cm advancement flap designed to close cheek component of defect after resection of lesion. C, Flap transferred. Nasal sidewall and lower eyelid components of defect repaired with full-thickness skin grafts. D, E, Postoperative views at 7 months. No revision surgery performed.

For defects of the medial cheek that cross the nasofacial sulcus, it is critical to preserve the sulcus by not advancing cheek flaps onto the lateral nasal sidewall to prevent blunting of this important aesthetic boundary line.5 To achieve this goal, a cheek advancement flap can be combined with a full-thickness skin graft. The cheek skin is advanced to the nasofacial sulcus and the standing cutaneous deformities are removed and used to graft the nasal sidewall. This divides the healing process into two distinct regions while maintaining a scar line in the sulcus. In the case presented, the advancement flap caused intraoperative inferior displacement of the lower eyelid margin. To eliminate the retraction, a second full-thickness skin graft was used to resurface the eyelid component of the defect and to relieve the tension on the eyelid caused by the flap.

The V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap is a unipedicle advancement flap without surrounding cutaneous attachments. The flap is designed as an inverted triangle. The base of the triangle becomes the advancing border of the flap. The flap is advanced into the defect on a mobile subcutaneous fat pedicle. The triangular secondary defect is closed by advancing skin adjacent to the donor site, creating a Y configuration of the wound closure. The island advancement flap is ideally suited for repair of defects of the superior melolabial fold (see discussion of this flap in Chapter 9). This is because the flap is dependent on ample subcutaneous fat for mobility and the medial cheek contains the greatest amount of facial fat.6 The flap is less effective in repairing medial cheek defects that are superior to the level of the alae. However, in these instances, a full-thickness skin graft combined with a V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap may offer an aesthetically acceptable alternative. Use of a skin graft in combination with the flap limits the required length of the flap and the necessary distance of advancement. Unlike rotation or bilobe transposition flaps, the island flap can be designed with most incisions in RSTLs. Ideally, the vertical limb of the Y is aligned in an aesthetic border, rhytid, or RSTL. Unlike with most other local cutaneous flaps, no standing cutaneous deformity is created with V-Y island advancement flaps, and thus there is no need to resect skin as when standing cutaneous deformities are removed.

Case 9

A 71-year-old woman developed a large area of atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia of the left cheek. Skin margins around the lesion were established by the square technique. The area requiring resection measured 4.5 × 4-cm. The resection margin encroached on the left lower eyelid and lateral canthus (Fig. 16-10A). A V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap was designed to cover a portion of the defect resulting from resection of the hyperplasia (Fig. 16-10B). It was not possible to completely close the defect with the flap because of the size and superior extent of the defect. Attempts to advance the flap to the superior margin of the defect would have caused downward traction on the eyelid. This in turn would almost certainly have caused lower eyelid retraction or ectropion. To avoid these problems, the 8 × 6-cm advancement flap was combined with a 3.5 × 2.5-cm full-thickness skin graft. The graft was used to close the superior portion of the defect near the lower eyelid (Fig. 16-10C). Because V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flaps do not generate a standing cutaneous deformity, the skin graft was harvested from the supraclavicular fossa. Figure 16-10D depicts the 11-month postoperative result.

FIGURE 16-10 V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, Atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia measuring 4.5 × 4-cm. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. B, An 8 × 6-cm V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap designed to close inferior portion of defect after resection of lesion. C, Lesion excised, flap advanced. A 3.5 × 2.5-cm full-thickness skin graft used to resurface superior portion of defect covered by bolster dressing. D, Postoperative view at 11 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 10

An 81-year-old woman developed lentigo maligna melanoma of the left cheek. Tumor-free margins around the skin lesion were obtained by the square technique (Fig. 16-11). She was referred for excision of the malignant neoplasm and reconstruction of the face. The area requiring resection measured 5 × 5-cm. As in Case 9, it was not possible to completely repair the skin defect resulting from tumor excision with a single local flap because of the size and superior extent of the defect. A 12 × 5-cm subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap was designed for repair of the inferior portion of the cheek defect once the malignant neoplasm was resected. A 5 × 2.5-cm full-thickness skin graft was harvested from the supraclavicular fossa and used to cover the superior portion of the cheek defect. Both flap and skin graft healed without necrosis or excessive scarring, with an acceptable aesthetic result. In spite of the distant donor site of the skin graft, color and textural match between the skin of the flap and the skin graft was nearly ideal.

FIGURE 16-11 V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap and full-thickness skin graft. A, Lentigo maligna melanoma measuring 5 × 5-cm. Tumor-free margins around lesion determined by square technique. A 12 × 5-cm V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap designed to close inferior portion of defect after resection of lesion. B, Tumor excised. Island flap mobilized on subcutaneous tissue. C, Flap in place. Superior portion of defect covered with full-thickness skin graft. D, E, Postoperative views at 6 months. No revision surgery performed.

Primary Wound Closure with Skin Graft

On occasion, cutaneous defects that are large in one dimension and small in the other dimension present a situation in which partial primary wound closure is possible without making incisions other than to excise the standing cutaneous deformities that form as a result of primary wound repair.

Case 11

A 69-year-old woman developed melanoma in situ of the left cheek. Tumor-free margins around the skin lesion were obtained by the square technique (Fig. 16-12). The area requiring excision measured 5 × 2.8-cm. The linear and relatively narrow configuration of the planned excision created a situation in which partial primary wound repair after excision was a reasonable approach. The standing cutaneous deformity resulting from advancement of the borders of the wound after resection of the melanoma was excised and used as a full-thickness skin graft to repair the small (1 × 1.2-cm) persistent skin defect of the lower eyelid. A cutaneous advancement flap would have been the best alternative method of wound repair. Partial primary wound closure avoided the need for incisions perpendicular to RSTLs, which would have been necessary to create an advancement flap. It also reduced the area of dead space created during wound repair compared with that necessary with use of an advancement flap. This reduced the risk for development of a postoperative hematoma or seroma.

FIGURE 16-12 Partial primary wound closure and full-thickness skin graft. A, A 5 × 2.8-cm melanoma in situ marked for excision. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) marked at inferior border of skin lesion. B, Melanoma excised. C, SCD excised. Partial primary wound repair completed. Excised SCD used as full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) to repair persistent 1 × 1.2-cm skin defect of lower eyelid. D, Gauze bolster in place over FTSG. E, F, Postoperative views at 4 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 12

A 72-year-old woman presented with melanoma in situ of the left cheek. Tumor-free margins around the skin lesion were obtained by the square technique. The area requiring excision measured 6 × 2.75-cm (Fig. 16-13). Similar to Case 11, the area requiring resection had a relatively linear narrow configuration. For this reason, partial primary wound repair was planned with skin grafting of the remainder of the wound after removal of the melanoma. The advantages of selecting this surgical approach for wound repair were the same as those listed in Case 11.

FIGURE 16-13 Partial primary wound closure and full-thickness skin graft. A, A 6 × 2.75-cm melanoma in situ marked for excision. B, After excision of melanoma, wound repaired by partial primary closure. Standing cutaneous deformity excised at inferior aspect of wound used as full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) to repair superior portion of wound. C, Postoperative view at 3 years. No revision surgery performed.

References

1. Baker, SR. Reconstruction of facial defects. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, et al, eds. Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 1998:527.

2. Baker, SR. Local cutaneous flaps in soft tissue augmentation and reconstruction in the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1994; 27:139.

3. Baker, SR. Options for reconstruction in head and neck surgery. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, eds. Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery, Update 1. St. Louis: Mosby; 1989:192.

4. Walike, JW, Larrabee, WF, Jr. The note flap. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985; 111:430.

5. Baker, SR. Nasal cutaneous flaps. In: Baker SR, ed. Principles of nasal reconstruction. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:103.

6. Clevens, RA, Baker, SR. Defect analysis and options for reconstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1997; 30:495.