CHAPTER 21 THE USE OF COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY IN INITIAL TRAUMA EVALUATION

In the 1970s, computed axial tomography (CT) revolutionized the evaluation and management of brain injury. Since then, advances in technology leading to increased speed and resolution have similarly changed the assessment of other injuries. Following the primary and secondary survey and initial plain radiographic evaluation, CT is often essential in the work-up of hemodynamically stable victims of blunt trauma. With the introduction of multidetector arrays, CT now may replace invasive catheter angiography and/or magnetic resonance imaging in certain circumstances.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF HEAD/BRAIN (CRANIUM)

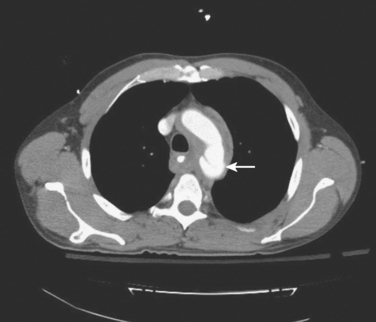

The study is performed without contrast. Acute hemorrhage appears white on the scan (Figure 1) except in very anemic patients, where it may appear isodense with brain. Active intracranial bleeding may also appear as gray swirls within the white clot, indicating hyperacute hemorrhage.

Figure 1 Computed tomography scan demonstrating a classic lenticular-shaped, acute epidural hematoma.

Computed tomography is very sensitive for intracranial hemorrhage, edema, and mass effect. As CT technology has advanced, detection of smaller lesions has become possible, leading to controversy regarding the significance of these lesions, and the indications for CT in mild head injury.1 CT of the brain may be normal and not correlate well with the clinical picture in patients with diffuse axonal injury.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF FACE AND ORBITS

Axial images are obtained using 3-mm slices from below the mandible to just above the frontal sinuses. The mandible may be excluded if no suspicion of injury is present. In a spiral CT scanner, coronal views can be reconstructed from the initial data. With multidetector CT scanners, 3D reconstructions (Figure 2) can be generated that are of value to the maxillofacial surgeon in planning reconstruction, and particularly in complex fractures.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF SPINE

The cervical spine needs to be evaluated radiographically in victims of blunt trauma who present with cervical spine tenderness, acute neurologic deficit, or significant brain injury; or who cannot be adequately evaluated due to distracting injury, intoxication, or therapy (particularly those who are intubated and sedated). Debate continues regarding some of the “softer” indications for such imaging.2 The mainstay of cervical spine imaging has been plain radiography for decades, with CT if the plain films are incomplete or inadequate, or the anatomy of injury requires delineation. Improvements in technology and technique have led some to advocate CT as the primary imaging modality for the cervical spine.3 The scan is done with 2.5–3-mm cuts from the skull base through the first thoracic vertebrae. In addition to the axial views, sagittal and coronal reconstructions are performed.

Computed tomography of the cervical spine has a sensitivity of 95%–100% and a specificity of 98%–100% for detecting cervical spine injury.4 Indications for imaging the thoracic and lumbar spine are similar to those for the cervical spine. Patients with spine tenderness, deformity, distracting injuries, neurologic deficit, or spine fractures at other levels, or who cannot be properly evaluated due to depressed mental status (with appropriate mechanism of injury) should have anteroposterior and lateral x-ray views of their thoracic and lumbar spine. If the plain films are inadequate or if the patient has an impressive clinical exam with normal plain radiographs, the area of concern should be further evaluated with CT. If the chest and abdomen have been scanned, detailed images of the spine can be reconstructed from that data. Images with a 2.5-mm slice thickness, including two normal vertebral bodies above and below the injury, should be obtained with sagittal and coronal reconstruction.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF NECK AND GREAT VESSELS

Patients with clinical signs of blunt neck injury, including laryngeal tenderness, subcutaneous emphysema, hemoptysis, hoarseness, hematomas, or significant contusions of the neck related to seat restraints should undergo CT of the soft tissues to evaluate the aerodigestive tract. CT is the study of choice to detect and define injuries or the larynx. Patients with cervical spine fractures (especially with transverse foramen involvement), severe facial fractures, basal skull fracture involving the carotid foramen, expanding hematoma in the neck, or with neurologic status not explained by traumatic brain injury, are at risk for cervical vascular injury. Although four-vessel cerebral angiography is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of blunt cerebrovascular injury, CT angiography has shown promising results in some series, and is a rapid approach to identification of carotid or vertebral artery injuries in this setting.5 For stable patients who have suffered penetrating neck trauma, CT-angiogram may be used to identify vascular, aerodigestive, and bony injuries, and may be useful to guide invasive studies and surgery.6

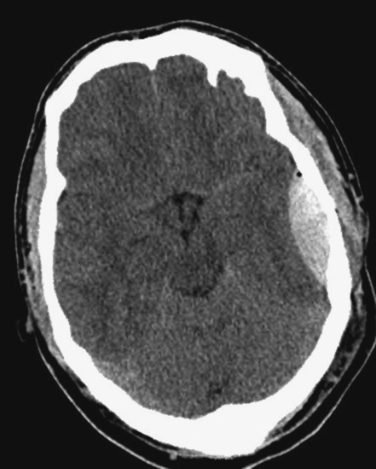

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF CHEST

Computed tomography of the chest is performed routinely following blunt trauma in many institutions, whenever an abdominal scan is obtained. Chest CT is specifically indicated when the initial chest radiography or mechanism of injury suggests likelihood of blunt thoracovascular injury. CT angiography has replaced traditional angiography as the initial study of choice for blunt aortic injury (Figure 3), and may completely eliminate the need for arteriogram for both operative and “nonoperative” management.7 Chest CT is also more sensitive for pneumothorax, hemothorax, pneumomediastinum, parenchymal lung injury, and bony thoracic injury, than plain chest radiography.

In hemodynamically stable transmediastinal gunshot wounds, a CT scan of the chest may be useful for initial screening to determine if further work-up or interventions are required.8

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF ABDOMEN AND PELVIS

The scan is performed in 5-mm slices from the lower chest through the perineum. In the trauma setting, there is no place for CT of the abdomen without concomitant pelvic CT. Intravenous contrast is used to enhance the solid organs and to detect active bleeding. A “blush” suggests active arterial bleed when seen in the area of a pelvic fracture, or in a solid organ injury, even in a stable patient (Figure 4). This finding should prompt an invasive approach to care, including interventional angiography and embolization and/or surgery.

Oral contrast is also frequently used, although many studies have demonstrated that it is not necessary in evaluating the gastrointestinal tract for injury. Radiologist preference and patient compliance should determine its use.9

In penetrating trauma, CT of the abdomen and pelvis may be useful in evaluating asymptomatic patients with stab wounds of the back or flank. In these situations, the triple-contrast technique yields sensitivity of 97%–100% and specificity of 96%–98% for retroperitoneal or abdominal visceral injury and peritoneal penetration. It may also be of value in identifying tangential gunshot wounds, at low risk for intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal injury. In institutions where nonoperative management of gunshot wounds of the liver is an option, CT of the abdomen of stable patients with suspicion of such injuries is a requirement.10,11

A CT cystogram can be performed in patients at risk for bladder injury. This has a diagnostic accuracy approaching 100%. Bladder distention is achieved by instilling at least 350 ml of diluted contrast solution via a Foley catheter under gravity. Postdrainage images are unnecessary.12

1 Stiell IG, Clement CM, et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in the patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005;294:1551-1553.

2 Griffen MM, Frykberg ER, et al. Radiographic clearance of blunt cervical spine injury: plain radiograph or computed tomography scan. J Trauma. 2003;55:222-226.

3 Sanchez B, Waxman K, et al. Cervical spine clearance in blunt trauma evaluation of a computed tomography-based protocol. J Trauma. 2005;59(1):179-183.

4 Hoffman JR, Mower WR, et al. Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in the patients with blunt trauma. National Emergency X-Radiology Utilization Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;343(2):94-99.

5 Miller PR, Fabian TC, et al. Prospective screening for blunt cerebrovascular injuries: analysis of diagnostic modalities and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):386-393.

6 Munera F, Soto JA, et al. Penetrating neck injuries: helical CT angiography for initial evaluation. Radiology. 2002;224(2):366-372.

7 Fabian TC, Davis KA, et al. Prospective study of blunt aortic injury: helical scan is diagnostic and antihypertensive therapy reduces rupture. Ann Surg. 1998;227(5):666-676.

8 Stassen NA, Lukan JK, et al. Reevaluation of diagnostic procedures for transmediastinal gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 2002;53(4):635-638.

9 Stuhlfant JN, Soto JA, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: performance of CT without oral contrast material. Radiology. 2004;233(3):689-694.

10 Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, et al. Penetrating torso trauma: triple contrast helical CT in peritoneal violation and organ injury—a prospective in 200 patients. Radiology. 2004;231(2):775-784.

11 Demetriades D, Gomez H, et al. Gunshot injuries to the liver: the role of selective nonoperative management. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188(4):343-348.

12 Deck AJ, Shaves S, et al. Current experience with computed tomographic cystography and blunt trauma. World J Surg. 2001;25(12):1592-1596.