Chapter 39 The urinary tract and its relationship to gynaecology

The close connection of the bladder to the vagina and the short urethra give rise to more problems in a woman’s urinary tract than in a man’s. The anatomy of the urinary tract is described on page 343. The function of the urinary tract is to permit waste products of metabolism to be removed from the body in the urinary flow. For this reason the mechanics of micturition will be discussed first.

MECHANICS OF VOLUNTARY MICTURITION

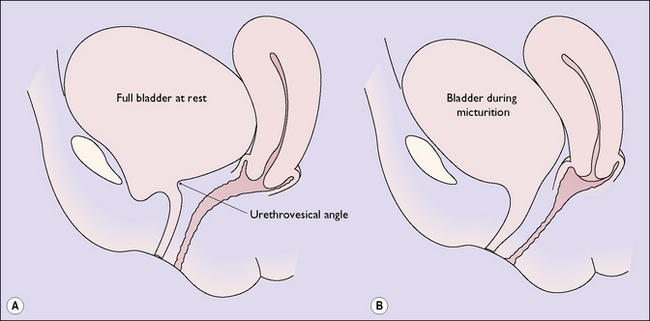

The bladder fills as urine trickles down the ureters. To accommodate the urine the bladder distends, and it can accommodate 300–400 mL of urine without any increase in the resting intravesical pressure, which remains below 10 cmH2O. In the resting state the urethrovesical junction is flat and there is an angle of about 90° between the bladder and the urethra (the urethrovesical angle) (Fig. 39.1A).

When the person is ready to pass urine the detrusor muscle is permitted to contract strongly, which raises the intravesical pressure above the intraurethral pressure. The detrusor contractions also cause funnelling of the bladder base and obliterate the urethrovesical angle (Fig. 39.1B).

URINARY INCONTINENCE (INVOLUNTARY MICTURITION)

In women two main and two subsidiary forms of urinary incontinence occur. The two main forms are:

The proportion of women complaining of the two main forms of incontinence is not known. The best estimates are shown in Table 39.1.

Table 39.1 Percentage prevalence of the types of urinary incontinence

| Type of Incontinence | Age (Years) | |

|---|---|---|

| <70 | >70 | |

| Urethral sphincter | 50 | 26 |

| Urge incontinence | 20 | 33 |

| Mixed | 30 | 41 |

Diagnostic measures to determine the cause of the incontinence

To try to identify the main (or the only cause) of the incontinence, tests should be arranged.

Treatment

Urethral sphincter incontinence

Unless the incontinence is severe, the choice of medical or surgical treatment should be offered to the patient. Obese women should try to reduce their weight, as this has been found to relieve incontinence in some cases. A chronic cough should also be treated. Postmenopausal women need additional treatment, especially if they have recurrent urinary tract symptoms. These symptoms occur because of atrophy of the urethral mucosa. The women should be treated for 2–3 months with an oestrogen vaginal pessary, ovoid or cream, as well as antibiotics if indicated. Pelvic floor exercises should be initiated (Box 39.1). The exercises must be continued for several months. An alternative, which many women may find more convenient, is the use of vaginal cones. Weighted vaginal cones (in sets of five weighing 20–90 g) are purchased. The woman inserts the lightest cone into her vagina. It is kept in by contraction of the levator ani muscle. She progresses from the lightest cone to the heaviest.

Box 39.1 Pelvic floor exercises

The exercises have three components:

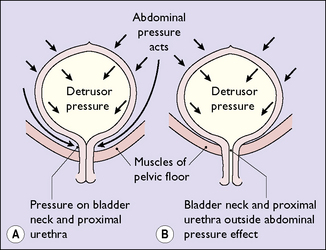

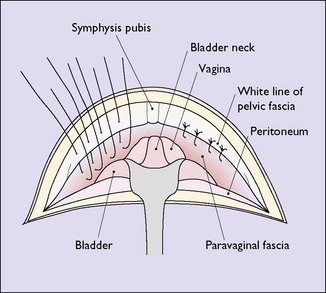

These measures effectively relieve urinary sphincter incontinence in up to 60% of affected women. If they fail, or the woman chooses surgery, several surgical approaches are possible. Most gynaecologists prefer an operation that elevates the bladder neck so that it lies within the abdominal pressure zone (Fig. 39.2) and provides support under the urethrovesical junction. One example is shown in Figure 39.3. Another option is tension-free vaginal tape (TVT), which can be inserted under regional or local anaesthesia as a same-day procedure. The operations have similar success rates of over 90% in the immediate postoperative years, but long-term studies show that 6 years after the operation only 75% of women are continent and 15–20% have detrusor instability. Uterovaginal prolapse is increased in some treated women. Whether this is due to the operation or to a general weakness of the uterovaginal supports, which also caused the incontinence, is not known.

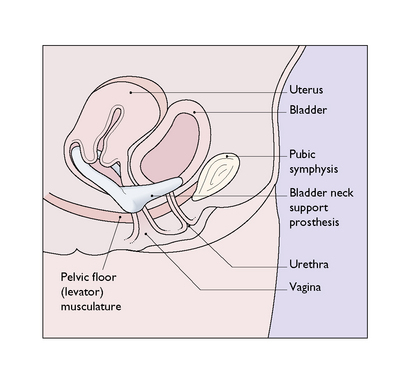

Women who are frail or who do not want surgery may be helped by using a bladder-neck support prosthesis. The device has two prongs, which elevate the urethrovaginal junction to its normal anatomic position (Fig. 39.4) without compressing the urethra. The device is removed at intervals for cleaning or if the woman has sexual intercourse. The appropriate size of prosthesis must be fitted by a doctor. A success rate of more than 80% is claimed.

URETHRAL PROBLEMS

Urethral prolapse

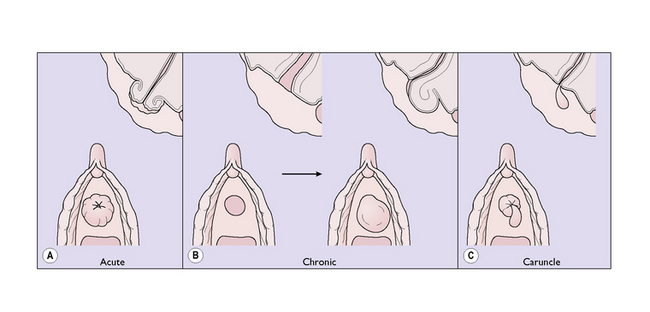

In the acute form, the entire circumference of the urethra suddenly everts and becomes engorged, as the venous return is impeded (Fig. 39.5A). The woman, who is usually elderly, complains of pain, dysuria and frequency. The immediate treatment is to reduce the prolapse and insert a catheter. Surgery may be offered later.

In the chronic form, atrophy of the urethral tissues may permit the external urinary meatus to gape and allow the posterior urethral wall to prolapse (Fig. 39.5B). The prolapse appears as a small red swelling and is painless. If it becomes infected, it becomes larger and painful. Treatment consists of applying an antiseptic ointment and an oestrogen cream. If the symptoms persist, surgery should be suggested.