The Unconscious or Confused Patient

BACKGROUND

Level of consciousness: assessment of the unconscious and confused patient

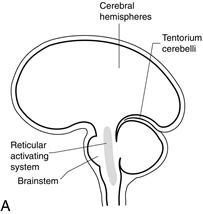

The reticular activating system in the brainstem maintains normal consciousness. Processes that disturb its function will lead to altered consciousness.

This can happen as a result of (Fig. 27.1):

Assessment of patients with altered consciousness will be divided into:

Examination of unconscious patients must:

• distinguish the three syndromes listed above

• attempt to define a cause—frequently requires further investiga- tions.

The terms used to describe levels of unconsciousness—drowsiness, confusion, stuporous, comatose—are part of everyday language and are used in different senses by different observers. It is therefore better to describe the level of consciousness individually in the terms described below. Some issues relating to confusion and delirium are discussed towards the end of the chapter.

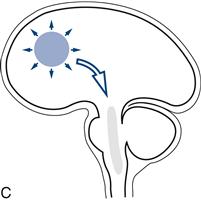

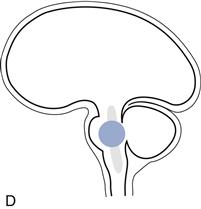

Figure 27.1 Sites of lesions that produce unconsciousness:

A. Key; B. Diffuse encephalopathy; C. Supratentorial lesions; D. Infratentorial lesions

Changes in level of consciousness and associated physical signs are very important and need to be monitored. Always record findings.

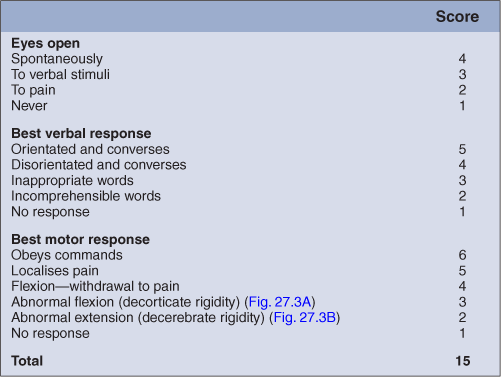

The Glasgow Coma Scale is a quick, simple, reliable method for monitoring level of consciousness. It includes three measures: eye opening, best motor response and best verbal response.

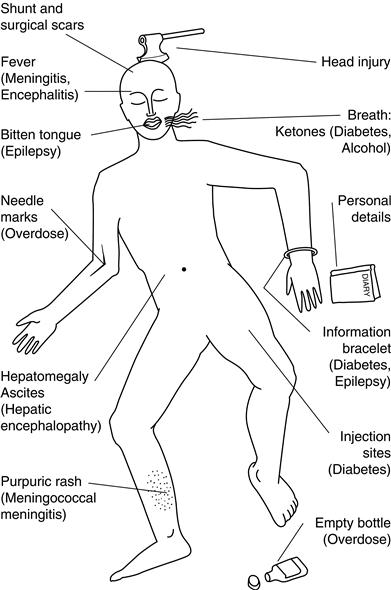

History can be obtained in patients with altered consciousness, from either friends, relatives, bystanders, or nursing or ambulance staff. The clothing (incontinent?), jewellery (alert bracelets/necklaces), wallet and belongings are silent witnesses that may help (Fig. 27.2).

Figure 27.2 Clues to diagnosis in the unconscious patient

Herniation or coning

Coning is what occurs when part of the brain is forced through a rigid hole, either:

There is a characteristic progression of signs in both types of herniation.

1 Uncal herniation

What happens

A unilateral mass forces the ipsilateral temporal lobe through the tentorium, compressing the ipsilateral third nerve and later the contralateral upper brainstem, and eventually the whole brainstem. Once cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow is interrupted, the process is accelerated by an increase in intracranial pressure.

Physical signs

Early:

Later:

Later still:

Progression is usually rapid.

2 Central herniation

What happens

A supratentorial lesion forces the diencephalon (the thalamus and related structures that lie between the upper brainstem and cerebral hemispheres) centrally through the tentorium. This compresses first the upper midbrain, and later the pons and medulla.

Physical signs

Early:

Later:

Later still:

Progression is usually slower.

WHAT TO DO

Resuscitation

Use the Neurological ABC:

N: Neck Always remember there may be a neck injury. If this is possible, do not manipulate the neck.

C: Circulation Check there is adequate circulation; check pulse and blood pressure.

D: Drugs Consider opiate overdose; give naloxone if indicated.

E: Epilepsy Observe for seizures or stigmata, bitten tongue; control seizures.

F: Fever Check for fever, stiff neck, purpuric rash of meningococcal meningitis.

G: Glasgow Coma Scale Assess score out of 15 (Table 27.1). Record subscores (eyes/verbal/motor) as well as total.

H: Herniation Is there evidence of coning? See above, rapid neurosurgical assessment.

N.B. Pulse, BP, respiration rate and pattern, temperature. Monitor Glasgow Coma Scale.

EXAMINATION

This is aimed at:

• finding or excluding focal neurological abnormalities

• looking for evidence of meningism

• determining the level of consciousness and neurological function.

Position and movement

What to do

Look at the patient: often best done from the end of the bed.

If there is movement:

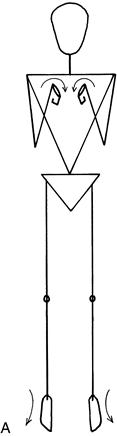

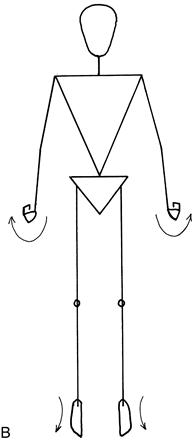

What you find

• Arms flexed at elbow and wrist, and legs extended at knee and ankle: decorticate posturing (Fig. 27.3A).

• Arms extended at elbow, pronated and flexed at wrist, and legs extended at knee and ankle: decerebrate posturing (Fig. 27.3B).

• Head falls to one side, with flexion of the arm: indicates hemiparesis.

• There are brief spasms, lasting less than a second, of arms or legs: myoclonus.

Best verbal responses

What to do

Try to rouse the patient.

Ask a simple question: ‘What is your name?’

If you get a reply:

• In person: What is your name? What job does that person do (pointing to a nurse)? What job do I do?

If you get no reply:

What you find

Note best level of response:

Head and neck

What to do and what you find

If there is evidence of trauma, do not test until cervical injury is excluded.

Eyelids

What to do and what you find

Look at the eyelids.

• Do they open and close spontaneously?

• Tell the patient to open/close his eyes.

Is the eyelid movement symmetrical?

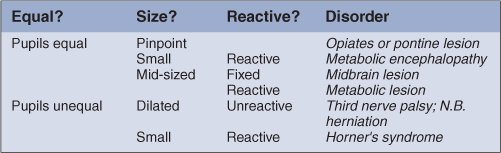

Pupils

What to do

Look at the pupils.

Fundi

Examine the fundi (Chapter 8).

Eye movements

What to do

Watch the eye movements.

• Do they follow a moving object, such as a torch?

• Do they move together (conjugately) or independently (disconju- gately)?

Test doll’s eye manœuvre (see below).

What you find

If the patient can follow objects:

• Test eye movements as in Chapter 9.

• Evidence of III, IV or VI nerve palsies, lateral gaze palsy (see Chapter 9 and consider uncal herniation).

Caloric test: see Chapter 12.

Corneal reflex: see Chapter 11.

Gag reflex: see Chapter 13.

Motor system

What to do

Assess the tone in all four limbs (see Chapter 16).

Assess the movement in each limb.

Ask the patient to move the limb.

Press the knuckle of your thumb into the sternum.

– Is there a purposeful movement to the site of pain?

– Do arms flex with this pain?

– Do arms and legs extend with pain?

Apply pressure to inner end of eyebrow. Note response.

Squeeze the nail bed of a digit in each limb: does limb withdraw?

WHAT YOU FIND AND WHAT IT MEANS

Patients with coma can be classified into one of the following groups:

1. Patients without focal signs

3. Patients with brainstem signs not indicative of coning (infra-tentorial lesions).

In most patients, accurate diagnosis depends on appropriate further investigations. These investigations are given in parentheses for the Common Causes of Coma.

COMMON CAUSES OF COMA

The most common are marked with an asterisk.

1 Diffuse and multifocal processes

a Without meningism

Metabolic

Toxin-induced

THE CONFUSED PATIENT—DELIRIUM

Some additional comments on patients with confusion or delirium.

Background

The cardinal features of delirium (or acute confusional state) are:

Patients may be apathetic or agitated and have delusions or hallucinations (often visual).

Delirium occurs with a diffuse encephalopathy (see Fig. 27.1B)—a process that leads to unconsciousness—coma—if more severe. This can arise from a wide range of causes (see later).

Delirium occurs more often in patients with a pre-existing cognitive deficit—and in those patients can arise with less severe provocation.

Patients with confusion are often difficult to assess; an approach is outlined here.

History will be limited. Obtain what information you can from witnesses, family members or members of staff—particularly about usual level of function and of anything to suggest a pre-existing cognitive deficit.

What to do

A complete general and neurological examination may be impossible if the patient will not co-operate—in which case, it is worth focusing on the most important elements.

Check pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate and glucose.

Check for neck stiffness.

Observe behaviour (see Chapter 3).

Check attention and concentration—using digit span and serial sevens.

If possible, check visual fields, eye movement, fundoscopy, facial symmetry, power in all four limbs, reflexes and plantar response. Sensory testing is likely to be limited.

What you find

• Patients may be agitated or apathetic with impaired attention and short-term memory.

• They may have signs of infection (especially important if prior neurological disorder):

– Non-specific—fever, tachycardia

– Non-neurological infection—for example, signs of chest infection or

– Neurological infection—purpuric rash, neck stiffness.

• They may have stigmata of other general medical disorder (see Fig 27.2).

What it means

All the diffuse and metabolic processes and supratentorial causes of coma (pages 204–5) can cause delirium. Some conditions such as alcohol withdrawal will cause confusion but not coma.

In addition, in patients with pre-existing cognitive deficits, a modest second pathology, particularly systemic infection—urinary tract infections or pneumonia—can present with delirium. Conversely, a systemic infection is much less likely to explain confusion in a patient who was previously normal.

The diagnosis of the cause of delirium depends on prompt further investigation.

A useful mnemonic to remind you of common reversible causes of delirium is WHIP TIME:

TIP

TIP

TIP

TIP TIP

TIP