Chapter 23 The Treatment of Adult Monteggia Fracture–Dislocations

Introduction

In 1814 Giovanni Battista Monteggia described two patients with a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna together with an anterior dislocation of the proximal epiphysis of the radius.1 However it was not until 1967 that Jose Luis Bado, Professor of Medicine at the University of Montevideo, Uruguay, proposed the term Monteggia fracture dislocation.2 He described ‘a group of traumatic lesions having in common a dislocation of the radio-humero-ulnar joint, associated with a fracture of the ulna at various levels or with lesions at the wrist’.

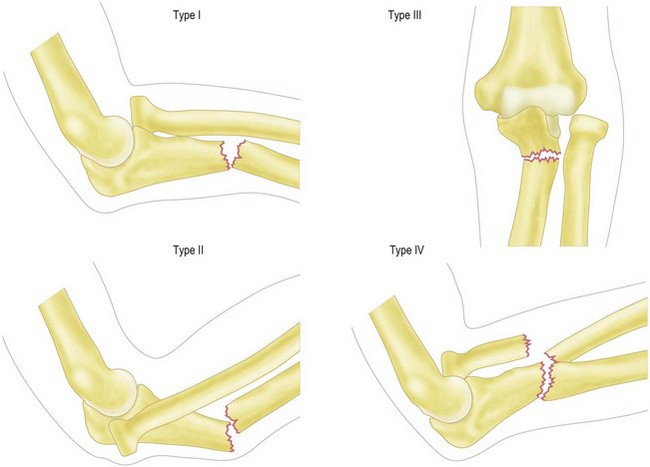

Bado classified these injuries into four types (Fig. 23.1):

Jupiter et al further subclassified type II Monteggia fracture dislocations into four groups depending on the position of the ulna fracture:3

More favourable clinical outcomes were noted with types IIB and IIC rather than types IIA and IID.

Background/aetiology

Adult forearm fractures are relatively uncommon, with an incidence of 0–4 per 10 000 population per annum.4 The observed odds ratio for 15- to 44-year-old males is 5.4.4 Within this group only 1–2% have a radial head dislocation allowing them to be termed a Monteggia fracture–dislocation.5

The most common mechanism of a type 1 fracture dislocation is thought to be a fall onto the outstretched hand with the elbow in extension and the forearm hyperpronated.2 In addition, a direct blow to the posterior aspect of the ulna will also produce this injury.

Evans, in a cadaveric study,6 removed all of the soft tissues from his specimens with the exception of the ligamentocapsular structures and interosseous membrane. As the forearm was taken into extreme pronation the ulna fractured, after which a gradual failure of the capsule and annular ligament resulted in an anterior dislocation of the radial head. By supination, regardless of the state of the ulna, Evans was able to reduce the radial head.

An alternative mechanism of injury proposed by Tompkins7 argues that the first phase of injury is an anterior dislocation of the radial head. This he states results from a fall onto the hyperextended elbow combined with a strong reflex biceps contracture. The axially loaded force applied to the shaft of the ulna combined with the pull of the brachialis and radius through the interosseous membrane then results in a proximal ulna fracture with the observed anterior angulation.

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Investigations

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the elbow, forearm and wrist are essential in order to avoid missing a Monteggia fracture–dislocation. Inadequate radiographs may fail to show the radial head dislocation, resulting in the patient being inappropriately treated for an isolated ulna fracture. The reported incidence of misdiagnosis varies from 16%8 to 52%.9

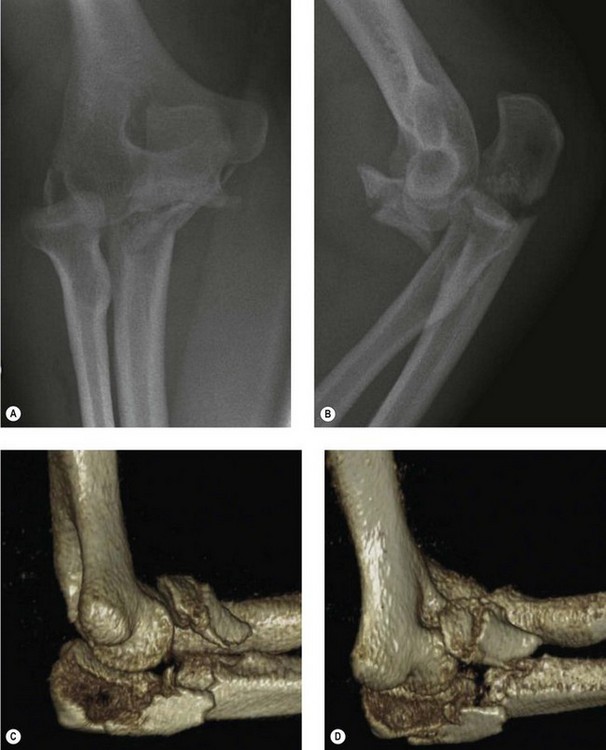

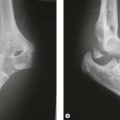

If doubt exists as to the extent of the patient’s injury, it is appropriate to obtain a CT scan of the elbow with three-dimensional reconstruction views in order to clearly define the anatomy of the radiocapitellar joint (Fig. 23.2).

Treatment options

In 1940 Speed and Boyd9 published their results of treating 30 acute and 32 chronic Monteggia type I fracture dislocations. They advocated open reduction and internal fixation of the ulna fracture and if needed reconstruction of the annular ligament with a ‘fascial loop’. In 1969 a further report from the same unit with 159 cases re-emphasized the importance of surgical management.10 This has also been recommended in other studies.11,12

Currently the accepted treatment option for adult Monteggia fracture dislocations is open reduction and rigid anatomical fixation of the ulnar fracture. Once this has been performed the radial head will either spontaneously reduce or will be reducible by closed manipulation.12 If, however, in addition to the radial head dislocation, there has been a radial head fracture then consideration must be given to reconstruction, excision or replacement of the radial head.

The treatment of paediatric Monteggia fracture dislocations is discussed in Chapter 12.

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

Surgical technique

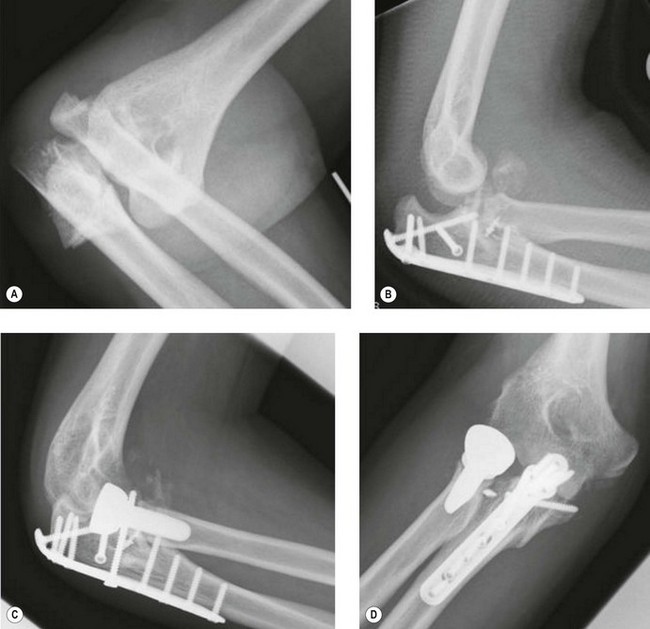

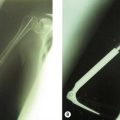

Preoperative planning is of paramount importance. The radiographs/CT scans must be carefully inspected for evidence of a radial head or coronoid fracture. If present, the surgical approach must enable access to these important structures since a failure to address these fractures can result in instability and poor outcome (Fig. 23.3).

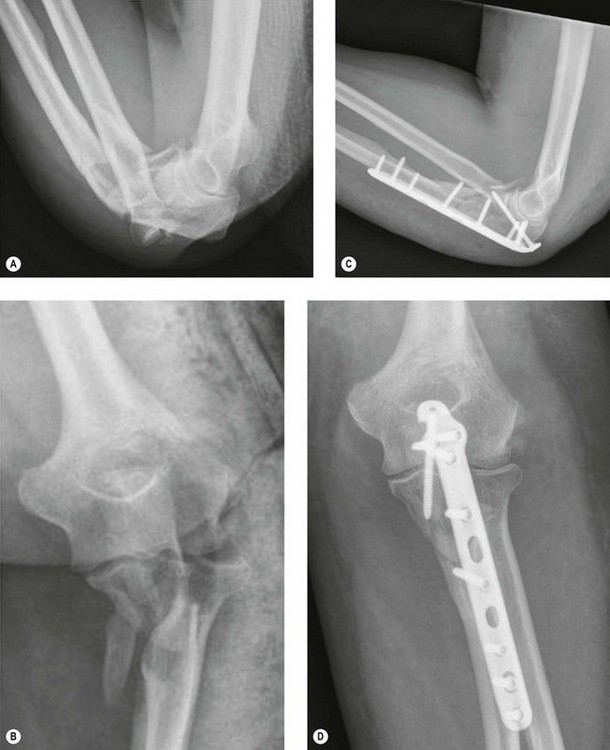

The ulnar fracture is identified. A two-part fracture can normally be reduced without great difficulty. Comminuted fractures, however, are more demanding, particularly if they involve the coronoid. In our experience the coronoid fragment is often displaced anteriorly and proximally. In this situation we have found it helpful to reflect the proximal ulnar fragment away from the surgical field as per an olecranon osteotomy. This facilitates identification of the coronoid fragment and allows reduction and temporary K-wire fixation of the fracture fragments from distal to proximal. The size of the coronoid fracture dictates the fixation method. If the fragment is large enough to accept one or two cortical screws, then these are inserted from the larger to the smaller fragments (Fig. 23.4). If the coronoid fragment is small, a fibre-wire suture is inserted in the anterior capsule and later tied around the ulna after the reconstruction has been completed. Once the coronoid fracture has been controlled the proximal ulnar fragment is anatomically repositioned and reduced to the reconstructed ulnar shaft.

Definitive fixation is then undertaken using a plate applied to the dorsal ridge of the ulna.13 This plate acts as a tension band device, neutralizing flexion moments at the fracture site during normal postoperative movement. Plates applied to the flatter medial or lateral surfaces of the ulna may result in failure of the metalwork and posterior angulation at the fracture site.5 The fixation should be robust enough to resist postoperative displacement forces until union has occurred. This can be achieved by contouring a low-profile compression plate14 or by using a pre-contoured anatomical proximal ulnar plate. The latter has the advantage that if the plate does not fit the ulna it is most likely that the bone is in the wrong position. Once the ulna has been anatomically reconstructed the radial head will spontaneously reduce in approximately 87% of cases15 or can be reduced by closed manipulation. This must be confirmed intraoperatively with a true lateral radiograph.

Occasionally the radial head becomes trapped and does not reduce. Structures that have been identified as preventing reduction include a tear of the capsule, the radial nerve16 and the biceps tendon wrapping around the radial neck.15 If closed reduction of the radial head cannot be achieved, open reduction must be undertaken, usually via a separate Kocher incision.

Radial head fractures occur commonly with Monteggia fracture dislocations and have a reported incidence in type II injuries of 70%.14 Provided they are recognized preoperatively the dorsal skin incision can be placed slightly more radially and extended more proximally. This will enable the radial skin flap to be elevated sufficiently such that a Kocher approach can be made to the radial head without the need for a separate skin incision.

If the fractured radial fragment is very small and unfixable, it is our practice to excise the fragment. However, excision of fragments involving more than 20% of the head can render the joint unstable.17 In this situation we excise the radial head and perform a radial head arthroplasty (Fig. 23.5).

Outcome including literature review

Until the mid 1980s adult Monteggia fracture–dislocations were reported to have a poor outcome.12,18 Out of 21 adult patients reported by Bruce et al,18 five had good outcomes, five fair and 11 poor. One synostosis and eight non-unions were also observed. The patients had a mixture of closed reduction, compression plating or intramedullary fixation of the ulna fracture with five open and 16 closed radial head reductions. In 1982 Reckling12 reported his experience of treating 30 patients with Monteggia fracture–dislocations. Nineteen were type I, five type II and six type IV. Six good results were observed in type I injuries, eight fair and five poor. In type II all five had a fair outcome and in type IV five had a fair and one a poor outcome. The reasons for the fair and poor outcomes are multiple and include a failure to address the coronoid and radial head fractures, inadequate internal fixation of the ulnar fracture and management of the ulnar shaft fracture by closed reduction.

Since the advent of contoured compression plating of the ulna with adequate management of coronoid and radial head fractures the results of treatment of adult Monteggia fracture–dislocations have improved, although they remain far from perfect. Ring et al14 showed satisfactory mid-term results in six out of seven patients with type I and 32 out of 38 patients with type II injuries. The average flexion extension arc was 110°. Ten patients (26%) with type II fracture dislocations had coronoid fractures and 26 (68%) had a radial head fracture. Only one of the patients with a type I injury (14%) had a radial head fracture and in this group no coronoid fractures were observed. Egol et al19 reported 11 satisfactory (good or excellent) results in a series of 20 adult patients. The overall SF-36 score of the patients was less than expected for the normal population and there was no correlation between Monteggia fracture–dislocation type and the final SF-36. Three cases progressed to non-union, of which two eventually united following revision of the fixation and bone grafting. The average flexion extension arc was just over 100° with 55° of supination. Interestingly, the six patients who required a radial head replacement had a worse outcome. Fourteen patients had radiographic features of arthrosis on follow-up, 11 of which were mild, one moderate and two severe. Korner et al20 reported the outcome of 49 adult Monteggia fracture–dislocations at an average of 83 months. Eighteen had type I and 22 type II injuries. Thirty-five had a satisfactory (excellent or good) outcome, with four cases of arthrosis being observed.

Complications

Radial nerve/posterior interosseous nerve palsy

The incidence of radial nerve palsy has been reported at between 3% and 30%.10,18 Expectant management is recommended, as the majority (94%) are neuropraxias and will normally show signs of recovery within 9 weeks of the fracture–dislocation. The most likely mechanism of injury is stretching of the nerve at the time of the radial head dislocation. The nerve is especially at risk in type II lesions. Stein et al, however, in a series of seven radial nerve palsies explored six which failed to recover.21 They noted a tight arcade of Frohse that they felt was responsible for compression of the nerve. When this was released, improvement in nerve function was noted. They argued that if the radial nerve is non-functioning then an expectant approach is acceptable. However, if only the posterior interosseous nerve is affected, the probability of a tight arcade of Frohse is high and warrants a more aggressive approach with surgical decompression if nerve recovery has not occurred by 3 months.

Non-union

If a stable construct is used and good fracture compression achieved at the time of primary surgery, the rate of non-union is low. However, in more comminuted fractures (IID and IV) with a greater severity of initial injury the chance of non-union increases. If this occurs, revision fixation with bone grafting is appropriate and will usually lead to fracture union. It is important, however, with non-unions to exclude an underlying infection since if present an aggressive debridement is required and the application of an external fixator may also be necessary.22

Stiffness

Contracture of the soft tissues around the elbow after trauma is well recognized. Anteriorly this involves the anterior capsule and brachialis, reducing elbow extension, while posteriorly the posterior capsule becomes thickened, reducing elbow flexion. In addition, failure to anatomically reduce the bony fragments at the time of reconstruction will result in bony impingement and a reduced range of elbow flexion and extension. The average flexion extension arc as reported in the literature is approximately 100° with supination of 55°. If the final range of movement achieved presents a functional problem for the patient an arthrolysis can be considered (Ch. 29).

Proximal radio-ulnar synostosis following a Monteggia fracture–dislocation occurs in less than 5% of cases.18 If encountered, surgical removal of bony bars may be appropriate. In our experience, however, there is often a soft tissue element to the restricted rotation such that even after removal of the heterotopic bone rotation remains limited. To reduce the risk of recurrence a prophylactic dose of radiotherapy immediately prior to surgery or the use of indomethacin postoperatively has been recommended,23 although more recent literature has questioned the safety of radiation as it could potentially increase the risk of non-union.24

1 Monteggia GB. Instituzioni Chirurgiche. Milan: Maspero; 1814. Vol 5

2 Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967;50:71.

3 Jupiter JB, Leibovic SJ, Ribbans W, Wilk RM. The posterior Monteggia lesion. J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5(4):395-402.

4 Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J. Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: the influence of age and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(2):243-248.

5 Eathiraju S, Mudgal CS, Jupiter JB. Monteggia fracture–dislocations. Hand Clin. 2007;23(2):165-177.

6 Evans EM. Pronation injuries of the forearm, with special reference to the anterior Monteggia fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31B(4):578-588.

7 Tompkins DG. The anterior Monteggia fracture: observations on etiology and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(6):1109-1114.

8 Reckling FW, Cordell LB. Unstable fracture dislocations of the forearm: the Monteggia and Galeazzi lesions. Arch Surg. 1968;96:999-1007.

9 Speed JS, Boyd HB. Treatment of fractures of ulna with dislocation of head of radius (Monteggia fracture). JAMA. 1940;115(20):1699-1705.

10 Boyd HB, Boals JC. The Monteggia lesion: a review of 159 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;66:94-100.

11 Bryan RS. Monteggia fracture of the forearm. J Trauma. 1971;11:992-998.

12 Reckling FW. Unstable fracture–dislocations of the forearm (Monteggia and Galeazzi lesions). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(6):857-863.

13 Simpson NS, Goodman LA, Jupiter JB. Contoured LCDC plating of the proximal ulna. Injury. 1996;27(6):411-417.

14 Ring D, Jupiter JB, Simpson NS. Monteggia fractures in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1733-1744.

15 Eglseder WA, Zadnik M. Monteggia fractures and variants: review of distribution and nine irreducible radial head dislocations. South Med J. 2006;99(7):723-727.

16 Watson JA, Singer GC. Irreducible Monteggia fracture: beware nerve entrapment. Injury. 1994;25(5):325-327.

17 Beingessner DM, Dunning CE, Beingessner CJ, et al. The effect of radial head fracture size on radiocapitellar joint stability. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2003;18(7):677-681.

18 Bruce HE, Harvey JP, Wilson JCJr. Monteggia fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(8):1563-1576.

19 Egol KA, Tejwani NC, Bazzi J, et al. Does a Monteggia variant lesion result in a poor functional outcome? A retrospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:233-238.

20 Korner J, Hoffmann A, Rudig L, et al. Montegia-Verletzungen im erwachsenenalter, eine kritische analyse von verletzungsmuster, management und ergebnissen. Unfallchirurg. 2004;107(11):1026-1040.

21 Stein F, Grabias SL, Deffer PA. Nerve injuries complicating Monteggia lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(7):1432-1436.

22 Regan AD, Morrey BF. Coronoid process and Monteggia fractures. In: Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J, editors. The elbow and its disorders. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:419-435.

23 Blokhuis TJ, Frölke JP. Is radiation superior to indomethacin to prevent heterotopic ossification in acetabular fractures? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(2):526-530.

24 Hamid N, Ashraf N, Bosse MJ, et al. Radiation therapy for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis acutely after elbow trauma: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(11):2032-2038.