The Throat

Anatomy and physiology

Oral cavity

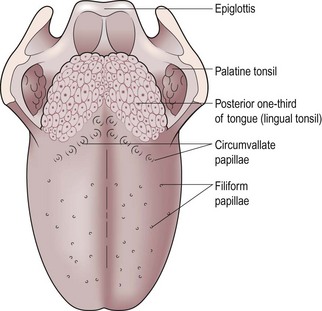

The tongue (Fig. 3.1) is a mass of interlacing muscle contained in a bag of cornified squamous epithelium. It contains numerous taste buds and is essential for efficient articulation, mastication and deglutition.

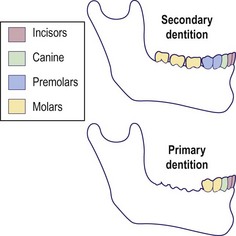

The teeth provide the mechanics for grinding food and are composed of enamel, dentine and cementum. The primary dentition of 20 teeth is completed by about 3 years. There are 32 teeth in the secondary (permanent) dentition commencing at about 6 years and complete by about 18 years (Fig. 3.2). The teeth-bearing alveoli of the maxilla are intimately related to the maxillary sinus. Occasionally the roots of the teeth may rest within the sinus cavity and lead to sinusitis secondary to dental disease.

Pharynx

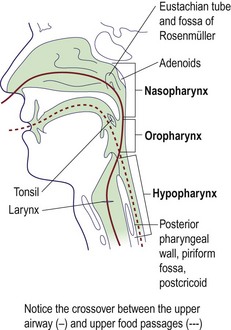

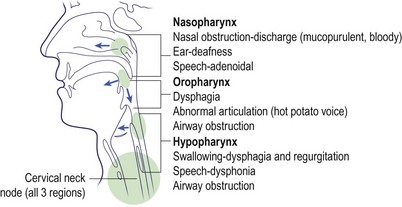

For clinical purposes the pharynx is divided into three regions:

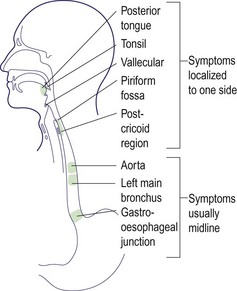

It stretches from the base of the skull above to the cricopharyngeal sphincter below. The oropharynx and hypopharynx, although primarily concerned with swallowing, are so closely related to the laryngeal inlet that pathology in these areas may cause symptoms and signs in adjacent regions. The important clinical structures in each part of the pharynx are shown in Figure 3.3.

Larynx

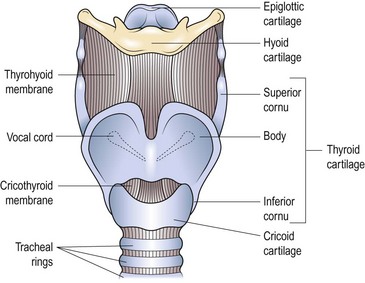

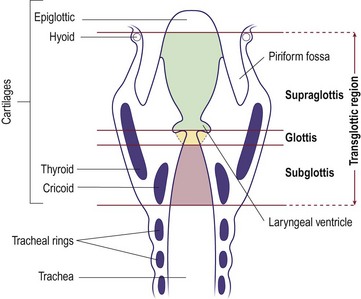

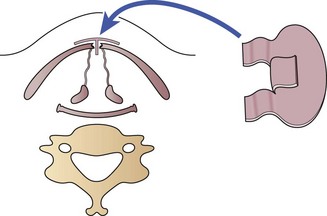

The primary function of the larynx is to protect the tracheobronchial tree. Through evolution it has developed the secondary function of voice production. It has a rigid skeleton consisting of several cartilaginous structures (Fig. 3.4). The most prominent of these is the thyroid cartilage, which inferiorly articulates with the cricoid cartilage. The flap-like epiglottis is attached to the thyroid cartilage and occludes the laryngeal inlet on contraction of the aryepiglottic muscles. The cricothyroid membrane provides a suitable site through which the airway can be maintained in an emergency (see p. 68).

For descriptive purposes the larynx is subdivided into three parts (Fig. 3.5):

Salivary glands

For clinical purposes there are three pairs of salivary glands:

The parotids produce a mainly serous saliva, and the submandibular glands secrete a seromucinous fluid. The parotid duct opens into the buccal sulcus opposite the second upper molar tooth. The submandibular duct opens into the floor of the mouth just lateral to the frenulum of the tongue. The sublingual glands open by multiple small ducts into the submandibular ducts and floor of the mouth. In addition, there are numerous minor salivary glands located throughout the oral cavity and pharynx. The functions of the salivary glands are related to the properties and volume of saliva (Table 3.1).

Nerve supply

Anatomy and physiology

Disease in the oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx may cause problems in adjacent structures.

Disease in the oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx may cause problems in adjacent structures.

The functions of the larynx are protection of the lower respiratory tract, phonation and Valsalva.

The functions of the larynx are protection of the lower respiratory tract, phonation and Valsalva.

Lymph nodes in the neck can become involved in primary and secondary pathologies.

Lymph nodes in the neck can become involved in primary and secondary pathologies.

An emergency airway can be maintained through the cricothyroid membrane.

An emergency airway can be maintained through the cricothyroid membrane.

Symptoms, signs and examination

Symptoms and signs

Oral cavity

The major signs and symptoms of oral disease include:

Pain

Dental disease is the most common cause of pain in the oral cavity. Carious teeth are tender if subjected to temperature changes and on chewing. Periodontal disease can cause pain on tooth brushing and is associated with halitosis due to accumulation of decaying food debris. Dentures may cause pain if improperly sized, or if they provide an abnormal bite. Atrophy of the teeth-bearing alveolar ridges may result in dentures causing pain, and is commonly seen in the elderly. Maxillary sinusitis may result in toothache if a tooth root is projecting into the sinus mucosa (Fig. 3.6). Pain due to malignant disease is severe and constant, and invariably leads to some degree of dysphagia.

Oral masses

Any complaint of a lump requires palpation of the site, even if a lesion is not visible. Virtually all lumps require biopsy to exclude cancer. Tongue masses are nearly always neoplastic. One exception is the rare, median rhomboid glossitis which presents as a red area on the dorsum of the tongue and is benign (p. 83).

Blockage of a duct of the sublingual salivary gland may give rise to a cystic lesion called a ranula in the floor of the mouth. An exostosis of the hard palate, ‘torus palatinus’, has a typical position in the midline and is hard to palpation (Fig. 3.7).

Pharynx

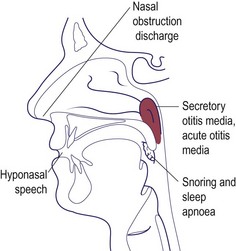

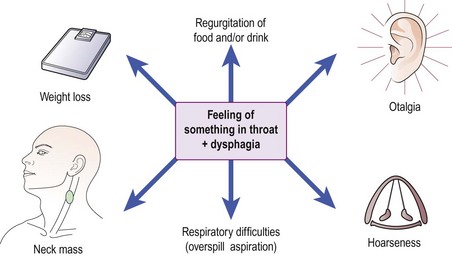

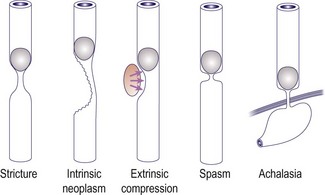

The precise symptoms are dependent on which region of the pharynx is primarily involved. The majority of pathologies in the oropharynx and hypopharynx, either inflammatory or neoplastic, will lead to some degree of dysphagia (p. 76) (Fig. 3.8). Deafness may occur due to obstruction of the Eustachian tube with nasopharyngeal pathologies. Progressive nasal obstruction and epistaxis with otological symptoms should alert the clinician to nasopharyngeal malignancy. Large oropharyngeal masses may cause a voice change (‘hot potato voice’) and respiratory obstruction.

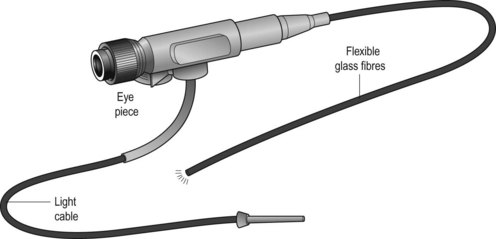

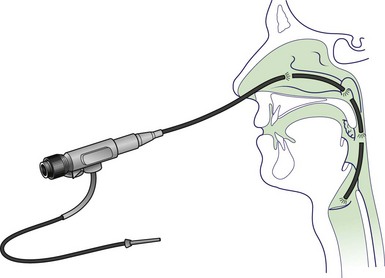

Examination

With experience it is possible to view the oral cavity and all parts of the pharynx and larynx using good illumination, tongue depressors and mirrors. These techniques are best learnt under supervision. Increasingly, laryngopharyngeal examination is carried out using a fibreoptic nasal endoscope (Fig. 3.9). Palpation plays a vital role in a full evaluation. Often, a lesion may be more easily felt than visualized, and its limits readily defined. Neck palpation is essential in all cases of head and neck neoplasia.

Imaging

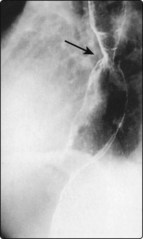

The value of plain radiology of the oral cavity is limited to viewing dental disease. Otherwise, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning is superior. However, lateral X-rays of the pharynx are useful, and may show evidence of abnormal shadowing. Contrast swallow studies may provide information on hypopharyngeal and oesophageal pathology (Fig. 3.10). A variety of radiological investigations of the salivary glands are available and are selected according to the suspected pathology (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2 Imaging techniques available in salivary gland pathology

| Suspected pathology | Imaging mode |

|---|---|

| Submandibular gland calculi | Plain X-ray/ultrasound scan |

| Sialectasis | Sialography |

| Parotid calculi | CT scan/ultrasound scan |

| Neoplasia | MRI/CT |

| Autoimmune disease | Radioisotopes |

Biopsy

Symptoms, signs and examination

Infective and neoplastic lesions of the upper air and food passages may present as enlarged neck glands.

Infective and neoplastic lesions of the upper air and food passages may present as enlarged neck glands.

All lumps should be palpated to assess their dimensions, consistency and fixity.

All lumps should be palpated to assess their dimensions, consistency and fixity.

All parts of the throat can be visualized on an outpatient basis.

All parts of the throat can be visualized on an outpatient basis.

Contrast studies are required in cases of hypopharyngeal or oesophageal pathology.

Contrast studies are required in cases of hypopharyngeal or oesophageal pathology.

Dysphonia I

Voice changes are often loosely described as hoarseness, but it is preferable to use the terms aphonia and dysphonia. Aphonia should be reserved for cases with no voice or a mere whisper. Dysphonia describes an alteration in the quality of the voice. Laryngeal disorders can present as dysphonia which may progress to stridor (p. 64). Organic causes of dysphonia may be broadly classified as in Table 3.3 and are discussed below. Other causes of dysphonia are considered on pages 62–63.

| Type | Cause |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory | Acute laryngitis (infective), chronic laryngitis |

| Neoplasia | Carcinoma larynx, respiratory papillomata |

| Neurological | Myasthenia gravis, carcinoma of lung/breast, post-thyroidectomy, spasmodic dysphonia |

| Systemic | Hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis |

Inflammatory laryngeal lesions

Polyps

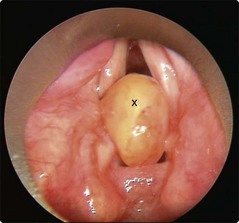

Unilateral inflammatory polyps are not uncommon (Fig. 3.11). The history is similar to acute laryngitis, but resolution of hoarseness cannot occur until the polyp is removed under microlaryngoscopic control. Inhalation of fumes, whether from tobacco, smoke or chemicals, may result in acute dysphonia. All inflammatory lesions, either infection or traumatic, may produce a sufficient degree of oedema to cause respiratory embarrassment.

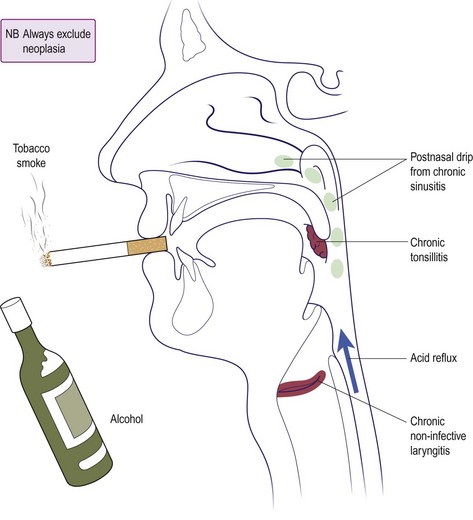

Chronic laryngitis

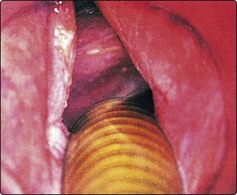

Chronic dysphonia is frequently due to chronic laryngitis. The risk factors are smoking, alcohol, laryngopharyngeal reflux and vocal abuse. The larynx may show hypertrophic epithelium and leukoplakia (Fig. 3.12). Such an appearance may herald neoplastic change, so biopsy is mandatory. If neoplasia has been excluded, management is directed to avoiding known aetiological factors.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is due to reflux of stomach contents above the lower oesophageal sphincter. Reflux above the lower oesophageal sphincter is called laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). The refluxate contains acid, enzymes (pepsin) and bile salts. All of these can be damaging to the larynx. Conventional 24 hour pH studies may not be diagnostic for LPR as they only screen for prolonged reflux episodes with a pH below 4. Transient reflux or less acidic refluxate may not produce heartburn (‘silent reflux’) but still lead to laryngeal symptoms such as dysphonia, cough and throat clearing. LPR is also a risk factor for laryngeal pathology such as chronic inflammation, vocal granulomas and even mucosal metaplasia (Fig. 3.12).

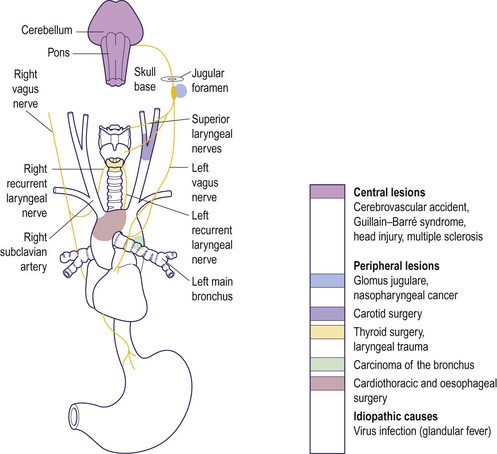

Neurological lesions

Once a vocal cord palsy has been diagnosed and any local laryngeal pathology excluded, a systematic approach is required to determine the aetiology. This is most easily done by considering the course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves. Because of its longer route, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is more frequently involved in pathology (Fig. 3.13). On the left this will be from the cranium via the skull base, neck and thorax back to the larynx; on the right it terminates in the neck. One of the most common causes of vocal cord palsy is malignant disease in the chest or neck, causing recurrent nerve deficits. Inspection of the neck may reveal the scar of previous surgery, e.g. carotid endarterectomy or thyroid surgery (Fig. 3.14). Unilateral vocal cord palsy, where history and examination do not reveal a cause, should therefore have CT imaging from brainstem to chest.

Systemic causes

A number of systemic conditions can produce dysphonia. These include the following:

Hypothyroidism can produce chronic oedema of the vocal cords. It is improved by appropriate medical therapy.

Hypothyroidism can produce chronic oedema of the vocal cords. It is improved by appropriate medical therapy.

Angioneurotic oedema, a manifestation of a type I allergic response, can cause laryngeal oedema which initially produces dysphonia, but may progress rapidly to respiratory obstruction.

Angioneurotic oedema, a manifestation of a type I allergic response, can cause laryngeal oedema which initially produces dysphonia, but may progress rapidly to respiratory obstruction.

Rheumatoid arthritis can result in fixation of the cricoarytenoid joint and vocal cord immobility. Such patients invariably have severe involvement of the small joints in the hands and feet.

Rheumatoid arthritis can result in fixation of the cricoarytenoid joint and vocal cord immobility. Such patients invariably have severe involvement of the small joints in the hands and feet.

Management

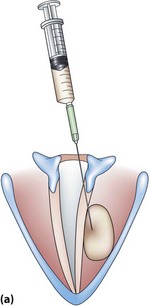

In many cases of unilateral cord palsy, no obvious aetiology is uncovered, despite extensive investigations. Such cases are eventually labelled idiopathic. Some recover spontaneously (which may take up to 6 months) or become asymptomatic as the contralateral mobile vocal cord compensates. If compensation in unilateral cord palsy is inadequate, then a medialization procedure may be beneficial. This involves techniques to medialize the palsied cord so that the mobile cord is more easily able to effect approximation (Fig. 3.15).

Dysphonia I

Should acute dysphonia not resolve within 3 weeks, ENT referral is mandatory to exclude neoplasia.

Should acute dysphonia not resolve within 3 weeks, ENT referral is mandatory to exclude neoplasia.

All cases of chronic dysphonia should be referred for laryngeal examination to exclude neoplasia.

All cases of chronic dysphonia should be referred for laryngeal examination to exclude neoplasia.

Avoidance of trauma (tobacco, voice abuse) will hasten resolution of acute dysphonia and improve chronic laryngitis.

Avoidance of trauma (tobacco, voice abuse) will hasten resolution of acute dysphonia and improve chronic laryngitis.

In children, acute-onset dysphonia, if due to inflammatory laryngeal lesions, can rapidly lead to total respiratory obstruction.

In children, acute-onset dysphonia, if due to inflammatory laryngeal lesions, can rapidly lead to total respiratory obstruction.

All vocal cord palsies, where history and examination are not diagnostic, should have a CT scan to image the course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves.

All vocal cord palsies, where history and examination are not diagnostic, should have a CT scan to image the course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves.

Dysphonia II

Dysphonia from non-organic causes may have a psychogenic or habitual aetiology. Specific laryngeal pathology may develop secondary to misuse or abuse of the voice. Table 3.4 classifies non-organic voice disorders. All age groups may be affected.

| Type | Cause |

|---|---|

| Habitual dysphonias | Vocal abuse |

| – acute laryngitis | |

| – vocal nodules | |

| – vocal oedema | |

| – chronic laryngitis | |

| – contact ulcer | |

| Psychogenic dysphonias | Musculoskeletal tension disorders |

| Conversion voice disorders | |

| – muteness | |

| – aphonia | |

| – dysphonia | |

| Mutational falsetto |

Habitual dysphonias

Vocal cord nodules

The nodule is located at the junction of the anterior and middle third of the vocal cord (Fig. 3.16). This is the area of maximum trauma at higher pitch levels seen in activities such as screaming and singing. The dysphonia is breathy and husky with a low pitch quality due to the mass loading of the vocal cords.

Vocal cord oedema and polyps

Mild oedema of the cords may resolve with improvement in the voice. More severe forms, such as Reinke’s, are best treated by microsurgical removal of oedematous tissue, preserving the overlying mucosa (Fig. 3.17). Tissue should always be sent for histological diagnosis.

Contact ulcers

Vocal abuse due to hyperadduction of the vocal folds may result in erosion of surface mucosa; particularly susceptible is the junction of the middle and posterior third of the vocal cord (Fig. 3.18). These are termed contact ulcers and can be sited at the vocal process of the arytenoids. The reaction can sometimes lead to considerable granulation tissue with the formation of a contact granuloma (Fig. 3.19). Gastro-oesophageal reflux may exacerbate or perpetuate this problem.

Psychogenic dysphonia

Musculoskeletal tension disorders

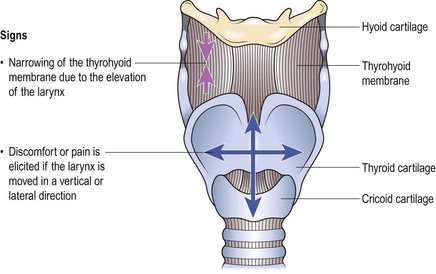

The cardinal features are a dysphonia and the presence of discomfort or pain around the larynx. The clinician can reproduce the pain by palpating the larynx (Fig. 3.21). Occasionally patients may complain of feeling a foreign body in the throat and difficulty in swallowing.

Mutational falsetto (puberphonia)

Dysphonia II

Any dysphonia not resolving within 4 weeks should have a mandatory ENT referral to exclude the presence of neoplasia.

Any dysphonia not resolving within 4 weeks should have a mandatory ENT referral to exclude the presence of neoplasia.

Acute-onset aphonia is invariably a conversion voice disorder.

Acute-onset aphonia is invariably a conversion voice disorder.

Most cases of puberphonia are psychogenic, not endocrine, in origin.

Most cases of puberphonia are psychogenic, not endocrine, in origin.

Vocal cord nodules are best treated by teaching correct vocal production. This may not be easy in young children.

Vocal cord nodules are best treated by teaching correct vocal production. This may not be easy in young children.

Chronic non-infective laryngitis with hyperplastic epithelial changes may be a precursor of cancer. It should be biopsied.

Chronic non-infective laryngitis with hyperplastic epithelial changes may be a precursor of cancer. It should be biopsied.

Stridor

Causes

Stridor results from a wide range of conditions which are summarized in Table 3.5 and discussed below.

| Age group | Cause |

|---|---|

| Neonatal* | Congenital tumours, cysts |

| Webs | |

| Laryngomalacia | |

| Subglottic stenosis | |

| Vocal cord paralysis | |

| Children* | Laryngotracheobronchitis |

| Supraglottitis (epiglottitis) | |

| Acute laryngitis | |

| Foreign body | |

| Retropharyngeal abscess | |

| Respiratory papillomata | |

| Adults | Laryngeal cancer |

| Laryngeal trauma | |

| Acute laryngitis | |

| Supraglottitis (epiglottitis) |

*Children are at greater risk than adults from upper airway obstruction because their airways are narrower and have softer cartilage, which collapses more easily.

General symptoms and signs of respiratory failure due to airway obstruction are given in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6 Signs of severe respiratory failure due to airway obstruction

Laryngotracheobronchitis

Supraglottitis

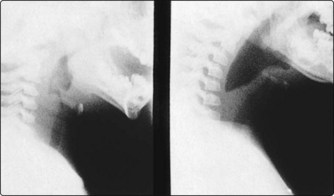

Supraglottitis (acute epiglottitis) is caused by group B Haemophilus influenzae and is characterized by gross swelling in the supraglottis (Fig. 3.22). It is seen primarily in 3–7-year-olds, although adults may also be affected. Clinical features include:

Subglottic stenosis

Subglottic stenosis may be congenital. Acquired cases are the result of the trauma of prolonged endotracheal intubation, particularly in premature births (Fig. 3.23). Clinical features include stridor on exertion, or with respiratory infection.

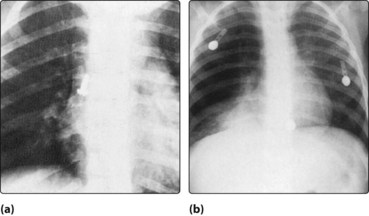

Foreign body obstruction

Inhalation of foreign bodies is most common in children. In adults, the problem is usually associated with psychiatric illness or alcohol intoxication. Objects can lodge anywhere in the laryngotracheobronchial tree (Fig. 3.24), and may remain symptomless for long periods. Common symptoms include:

sudden onset of coughing, wheezing or stridor in a previously healthy child

sudden onset of coughing, wheezing or stridor in a previously healthy child

chest infection resulting from a foreign body in a smaller airway.

chest infection resulting from a foreign body in a smaller airway.

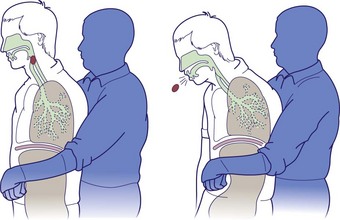

In a child, a foreign body may be dislodged by holding the patient up by the legs and giving a sharp slap on the back. The Heimlich manoeuvre can be used in both adults and children (Fig. 3.25). There should be a low threshold for tracheobronchoscopy in a child who has had a significant choking episode, even in the absence of clinical signs or radiological findings.

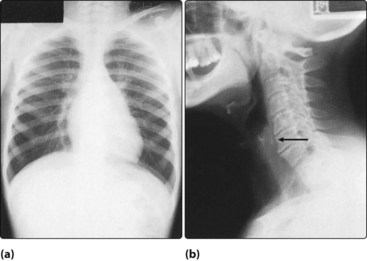

Retropharyngeal abscess

A now rare condition, retropharyngeal abscesses occur mostly in young infants and children. Inflammation and swelling in the retropharyngeal space, secondary to oropharyngeal infection, can cause respiratory embarrassment and severe dysphagia (Fig. 3.26). The child assists breathing by hyperextension of the neck, which is held rigid. Urgent parenteral antibiotics are administered and surgical drainage is performed to avoid spontaneous rupture with risk of inhalation of pus.

Respiratory papillomata

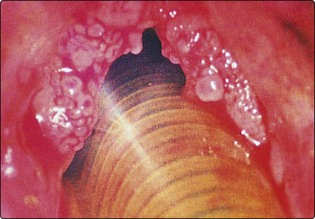

Respiratory papillomata are characterized by warty lesions appearing in the larynx caused by the human papilloma virus (Fig. 3.27). The trachea, bronchi and pharynx may be involved in florid cases. They are thought to be due to ascending uterine infection; however, acquired cases in adults may be due to genetic predisposition or be sexually acquired. Clinical features include stridor and hoarseness.

Acute laryngitis

Stridor

Intubation is preferable to tracheostomy in severe cases of laryngotracheobronchitis and supraglottitis.

Intubation is preferable to tracheostomy in severe cases of laryngotracheobronchitis and supraglottitis.

Suspect an inhaled foreign body in a previously well child who develops abrupt wheezing or stridor.

Suspect an inhaled foreign body in a previously well child who develops abrupt wheezing or stridor.

Inhaled foreign bodies may remain symptomless for long periods.

Inhaled foreign bodies may remain symptomless for long periods.

Radiolucent foreign bodies are not uncommon, so do not rely on radiology.

Radiolucent foreign bodies are not uncommon, so do not rely on radiology.

Laryngotracheal injury

The incidence of laryngotracheal trauma has decreased markedly with the compulsory wearing of car seat belts. Most injuries now occur as a result of sporting activities (karate, ice hockey, etc.), but also from knives and bullets. Inhalation of smoke and ingestion of corrosives may cause severe laryngeal oedema. Clumsy laryngeal intubation for anaesthesia, or if required for long-term ventilation, may lead to chronic laryngotracheal problems (Table 3.7).

| Type | Cause |

|---|---|

| Penetrating injuries | Knives, glass, etc. |

| Blunt injuries (minor & major) | Road traffic accidents |

| Sports (karate) | |

| Miscellaneous | Smoke inhalation |

| Corrosive ingestion | |

| Intubation |

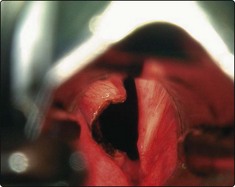

Injuries to the larynx are usually produced when the laryngeal framework is crushed against the bony cervical vertebrae (Fig. 3.28). Damage is usually more severe in the elderly where ossification reduces the resilience of the laryngeal cartilages.

Management

It is vital to consider the existence of laryngotracheal injury in trauma to the upper body. Flexible laryngoscopy is essential to provide an assessment of laryngeal damage and compromise. Maintenance and protection of the airway are major priorities in acute trauma, hence intubation or tracheostomy may be required urgently. Once the airway is secure, CT imaging should be considered to further assess the injury and early reconstruction should be planned (Table 3.8).

| Type of injury | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Penetrating injuries | Drain any laryngeal haematoma |

| Exploration to remove penetrating object, e.g. bullet | |

| Reconstruct cartilage fractures | |

| Minor blunt injuries | Observe. Intubate only if laryngeal oedema causes airway obstruction |

| Laryngeal exploration and reconstruction may be needed | |

| Major blunt injuries | Usually require intubation, laryngeal exploration and laryngeal reconstruction |

| IN ALL CASES ENSURE A SECURE AIRWAY AND CONTROL HAEMORRHAGE | |

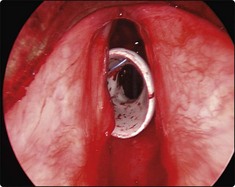

Indwelling soft stents may support the laryngeal framework and prevent stenosis if left in for 1–2 weeks (Fig. 3.30).

Chronic laryngotracheal stenosis

In adults, chronic compromise of the airway may be due to a number of causes:

Subglottic/tracheal stenosis

Adult subglottic or tracheal stenosis is increasingly common and often misdiagnosed as asthma (Fig. 3.31). Advances in medical care mean that more patients are surviving periods of ventilation on intensive care units. However, injury is often sustained to the airway and one or more of the following factors may play a role:

traumatic endotracheal intubation

traumatic endotracheal intubation

endotracheal tube too large or cuff pressures too high

endotracheal tube too large or cuff pressures too high

delay in changing to tracheostomy

delay in changing to tracheostomy

incorrectly sited tracheostomy

incorrectly sited tracheostomy

some patients having an intensive inflammatory response to foreign materials in the airway.

some patients having an intensive inflammatory response to foreign materials in the airway.

Management

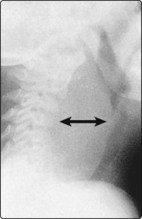

It is sometimes possible to visualize a subglottic stenosis using a flexible laryngoscope. The site, degree and length of the stenosis can be determined using lateral neck X-rays. A CT scan is often more helpful (Fig. 3.32). Respiratory function tests will help to gauge the degree of disability related to the stenosis. However, some patients have a tracheostomy and these tests are not always possible.

Tracheal or subglottic stenosis, if minor, may be treated with cruciate cuts using a knife or laser and dilatation. If the stenosis is more severe, it may require temporary stenting (Fig. 3.33).

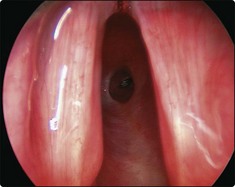

Bilateral vocal cord palsy

Bilateral vocal cord palsy may be congenital or acquired. The vocal cords come to lie in the median or paramedian position. Although voice or cry may be good, there is usually stridor and dyspnoea. Congenital bilateral cord palsy will often recover as the child grows and the only treatment necessary may be a temporary tracheostomy. Acquired bilateral cord palsy is most commonly iatrogenic, following surgery on the neck or thorax, and the patient is usually reintubated or an emergency tracheostomy carried out. It is possible to remove the tracheostomy tube following a procedure on the vocal cords. The vocal cords can be lateralized surgically or an airway is lasered out from the back of one vocal cord (Fig. 3.34). The patient may subsequently be decannulated but will have a weak and ‘breathy’ voice.

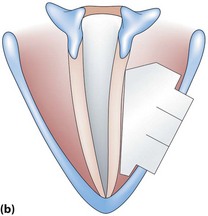

Glottic webs

Larger webs are also divided but, in addition, may require the insertion of a Silastic sheet into the anterior commissure or a laryngofissure approach and the insertion of a keel (Fig. 3.35).

Laryngotracheal injury

Severe laryngotracheal trauma may not be associated with significant external neck signs.

Severe laryngotracheal trauma may not be associated with significant external neck signs.

Laryngotracheal trauma may be missed if severe injury has occurred to other parts of the body.

Laryngotracheal trauma may be missed if severe injury has occurred to other parts of the body.

All laryngotracheal trauma patients should have a laryngoscopy to assess damage.

All laryngotracheal trauma patients should have a laryngoscopy to assess damage.

Priority in management is protection and maintenance of the airway and arrest of haemorrhage.

Priority in management is protection and maintenance of the airway and arrest of haemorrhage.

Early laryngotracheal surgery, if necessary, will largely prevent the difficult management problem of chronic laryngotracheal stenosis.

Early laryngotracheal surgery, if necessary, will largely prevent the difficult management problem of chronic laryngotracheal stenosis.

Maintenance and protection of the airway

Upper respiratory obstruction

Life-threatening respiratory obstruction

Life-threatening respiratory obstruction is usually due to inhalation of foreign bodies or infections of the laryngotrachea. Children are more likely to be involved than adults. Wide-bore needles may be inserted directly into the trachea to provide temporary relief (Fig. 3.36) until either intubation or tracheostomy can be performed.

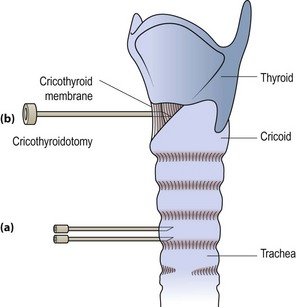

A similar approach is feasible with the airway entered through the cricothyroid membrane (cricothyroidotomy) (Fig. 3.36). The membrane is easily palpable between the cricoid ring and inferior border of the thyroid cartilage. Any sharp object, e.g. a knife or scalpel, is inserted into the region and rotated once the airway is entered. Any available tube, e.g. a catheter or the barrel of a pen, is inserted to maintain the airway until intubation or a formal tracheostomy is performed.

Gradual-onset obstruction

It is imperative not to allow the clinical situation to deteriorate to one of life-threatening obstruction. Increasing stridor, the use of accessory muscles of respiration, tachypnoea, tachycardia and intercostal recession are worrying signs (see Table 3.6, p. 64).

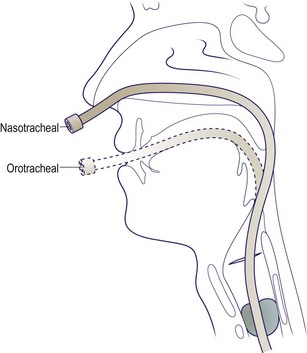

In all age groups endotracheal intubation should be attempted only by an experienced anaesthetist (Fig. 3.37). This may require additional techniques with a rigid bronchoscope or flexible laryngoscope as aids in difficult intubations. An ENT surgeon should be standing by to perform a tracheostomy if intubation fails. Tracheostomy in children should, for a variety of reasons, be avoided (see Table 3.10, p. 70), except in an emergency.

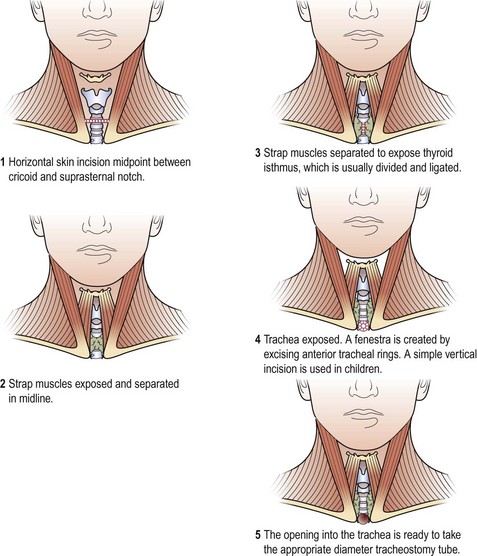

Elective tracheostomy

The technique of elective tracheostomy is illustrated in Figure 3.38. The skin incision is made midway between the cricoid ring and suprasternal notch. The strap muscles are identified, running in the vertical plane, and separated in the midline. The thyroid isthmus should be divided and transfixed to avoid thyroid tissue falling into the tracheal window. In adults, a small window is then cut in the trachea between the second and third, or third and fourth tracheal rings. In children, a vertical incision is made to avoid transecting the trachea. The cricoid cartilage and the first tracheal ring must not be compromised, otherwise there is a high risk of late subglottic stenosis.

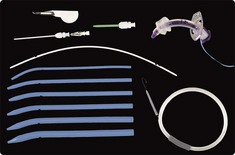

There are several percutaneous tracheostomy kits available. All are based around insertion of a needle into the cervical trachea, which allows a guidewire to be passed. An opening into the airway, large enough to insert a tracheostomy tube, is created using serial dilators (Fig. 3.39) or using dilation forceps or a single dilation.

The subsequent care of the tracheostomy should be meticulous in order to avoid severe complications. It is imperative to instruct the nursing staff appropriately (see Fig. 3.40, p. 70).

Protection of the tracheobronchial tree

Protection from bronchial secretions

The modern technique is to manage these patients by inserting a percutaneous tracheostomy (Fig. 3.39). This method avoids an open procedure and may be performed by either critical care clinicians or ENT surgeons.

Respiratory failure

Maintenance and protection of the airway

Life-threatening respiratory obstruction requires immediate relief. Insert needles into the trachea or perform a laryngotomy in adults.

Life-threatening respiratory obstruction requires immediate relief. Insert needles into the trachea or perform a laryngotomy in adults.

In children, intubate rather than perform tracheostomy.

In children, intubate rather than perform tracheostomy.

Sputum retention may be overcome with a ‘minitracheostomy’.

Sputum retention may be overcome with a ‘minitracheostomy’.

In general, it is better to intubate than to perform a tracheostomy.

In general, it is better to intubate than to perform a tracheostomy.

In performing a tracheostomy ensure that the cricoid cartilage and first tracheal ring are not compromised.

In performing a tracheostomy ensure that the cricoid cartilage and first tracheal ring are not compromised.

Postoperative care and complications of artificial airways

The old adage that ‘the time to do a tracheostomy is when you first think of it’ is still very apt. In acute or critical airway situations the endotracheal tube is the preferred means of securing the airway (Table 3.9). If it is anticipated that the patient will require ventilation for periods greater than 7–10 days, a surgical or percutaneous tracheostomy should be planned. The threshold for carrying out a tracheostomy in a child is higher than in an adult for the reasons indicated in Table 3.10.

Table 3.9 Advantages of endotracheal intubation over tracheostomy

Intubation is a quicker procedure than tracheostomy

Clinicians skilled in intubation are more numerous and readily available than those skilled in tracheostomy

Tracheostomy is more easily performed in an intubated anaesthetized patient

The early complications of intubation are rarer and less severe than those of tracheostomy

Table 3.10 Reasons for avoiding a tracheostomy in a child

Most causes of respiratory obstruction in children are infective in origin and will resolve sufficiently within 72 hours to allow extubation

A tracheostomy is more hazardous to perform, due to a short neck, the presence of the thymus and a high brachiocephalic artery

Removal of a tracheostomy tube is difficult in children due to development of subglottic oedema with granulations

Postoperative tracheostomy care

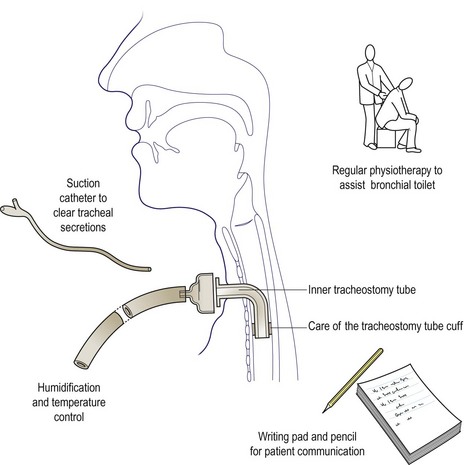

Postoperative care of a tracheostomy needs to be meticulous to avoid complications (Fig. 3.40). The nose assists in warming and humidifying inspired air, and this function is bypassed after tracheostomy. Copious tracheal secretions occur as a consequence and the situation is further compounded by the patient’s inability to cough satisfactorily. Regular humidification prevents the formation of dried crusts. Chest physiotherapy assists in this bronchial toilet.

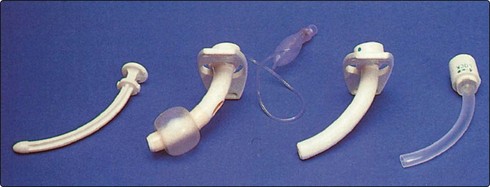

Crusting tends to occur at the tip and within the lumen of the tracheostomy tube. A single-lumen tube requires regular removal, cleaning and reinsertion. The modern double-lumen tubes have considerable advantages (Fig. 3.41). The inner tube can be removed without disturbing the outer tube. With modern low-pressure high-volume cuffs, regular deflation is not required.

For the immediate postoperative period a writing pad should be provided for communication as the patient will be unable to speak. With a fenestrated tracheostomy tube a speaking valve can be fitted to help the patient to talk (Fig. 3.42).

Complications of tracheostomy

The complications of tracheostomy are summarized in Table 3.11. Immediate complications include bleeding from the thyroid or anterior jugular veins. Air embolism is fortunately extremely rare.

| Stage | Complication |

|---|---|

| Operative | Haemorrhage |

| Air embolism | |

| Cricoid injury | |

| Surgical emphysema | |

| Pneumothorax | |

| Postoperative | |

| Early | Tracheitis and tracheal crusting |

| Atelectasis | |

| Tube blockage | |

| Dysphagia | |

| Tracheal erosion | |

| Late | Tracheomalacia |

| Laryngotracheal stenosis | |

| Decannulation problems | |

| Tracheocutaneous fistula/scar | |

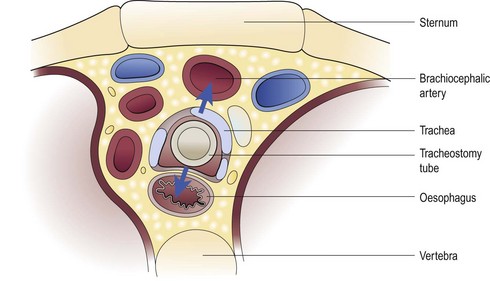

Tracheal necrosis may occur as a result of the tracheostomy tube sitting incorrectly within the tracheal lumen. This may lead to erosion of the brachiocephalic artery and a fatal haemorrhage. Necrosis, if sited posteriorly, can result in a tracheo-oesophageal fistula (Fig. 3.43).

Late complications such as decannulation difficulties and tracheal stenosis may be encountered. The former is frequently due to granulations narrowing the lumen at the stomal site. Decannulation can be effected, by weaning, if the tracheal patency is satisfactory. This involves the insertion of tracheostomy tubes of decreasing diameter until the patient can breathe with the tube occluded. Tracheal stenosis may be the end result of scarring caused by inflatable cuffs or incorrect tracheal incisions. Skin scarring in the form of web or keloid can be unsightly. Transverse incisions made in the head-neutral position result in fewer such problems (Fig. 3.44).

Postoperative care and complications of artificial airways

Proper nursing care is essential after tracheostomy.

Proper nursing care is essential after tracheostomy.

Adequate humidification, tracheal suction as required and physiotherapy will keep the chest free of secretions and prevent complications due to crusting.

Adequate humidification, tracheal suction as required and physiotherapy will keep the chest free of secretions and prevent complications due to crusting.

Most complications of tracheostomy are due to improper surgical technique, inflated cuffs or incorrectly shaped or sited tracheostomy tubes.

Most complications of tracheostomy are due to improper surgical technique, inflated cuffs or incorrectly shaped or sited tracheostomy tubes.

Sore throats

Sore throat is probably one of the most common symptoms encountered in medicine. Patients use the term to describe almost any feeling in the throat, ranging from dryness to actual pain. It is important therefore to ascertain the precise nature of the ‘sore throat’ early in the clinical history. The primary feature may be pain, but its severity may lead to dysphagia for solids, liquids and occasionally saliva. It is useful to consider separately sore throats in children and adults, although no clinical entity is exclusive to either group (Table 3.12).

| Age group | Aetiology |

|---|---|

| Children | Acute pharyngitis, acute tonsillitis, glandular fever, blood disorders, diphtheria |

| Adults | |

| Acute | Tonsillitis, pharyngitis, peritonsillar abscess, candidiasis (AIDS) |

| Chronic | Tonsillitis, pharyngitis (tobacco, alcohol), gastric reflux, vitamin deficiency, elongated styloid process |

Sore throats in adults

Acute sore throats

Infective conditions

If viral in origin, there is invariably a runny nose and a productive cough due to chest infection. The presence of mucopus on the pharyngeal wall implies bacterial infection. Although throat swabs are not always helpful, they may rule out bacterial infection. The treatment is symptomatic. Oral analgesics and adequate fluid intake with bed rest are required for 3–4 days to allow the disease to resolve spontaneously. Antibiotics are administered only if bacterial infection is suspected. Acute tonsillitis is uncommon in adults in comparison to its frequency in children. The clinical approach is similar in both age groups (p. 73).

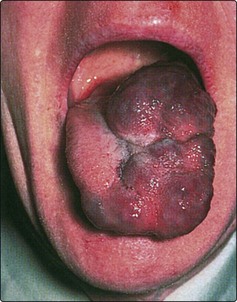

Candidal infection can give rise to a painful throat and is not uncommon in the immunocompromised, e.g. diabetics, and patients undergoing radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and those afflicted by lymphomata. The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) also increases the risk of such fungal infection. Diagnosis is made by noting the typical appearance and culture (Fig. 3.45). Treatment may be either local antifungal agents or parenteral administration if the patient also has systemic infection.

Peritonsillar abscess

A peritonsillar abscess is a condition in which pus forms between the tonsil capsule and the superior constrictor muscle. This will be preceded by a period of peritonsillar cellulitis. The patient has symptoms of severe unilateral sore throat causing dysphagia. This may lead to an inability to swallow even saliva, resulting in dribbling. The voice has a ‘hot potato voice’ quality. Trismus may be so prominent that visualization of the oropharynx is difficult. Ipsilateral otalgia and cervical adenopathy are other features. The most obvious clinical sign is a unilateral tonsillar inflammation causing deviation of the base of the uvula (Fig. 3.46).

Chronic sore throats

Any patient with a chronic sore throat should be suspected of harbouring a malignancy in the oral cavity or pharynx. Associated cardinal symptoms, such as weight loss, dysphagia, hoarseness, and a history of smoking and excessive alcohol intake, make such a diagnosis more likely (see Fig. 3.54, p. 76).

The most common cause of a chronic sore throat in adults is chronic pharyngitis. This inflammation is multifactorial and non-infective (Fig. 3.47). Tobacco smoke and alcohol are particularly irritant to the pharyngeal mucosa. Chronically infected tonsils, characterized by infected white debris in the tonsillar crypts, can produce a discomfort in the throat. A hiatus hernia with acid reflux can also result in a constant sore throat due to pharyngeal inflammation. Management involves conservative measures to reduce or abolish the effect of irritating agents and tonsillectomy in selected cases.

Sore throats in children

Acute sore throats

Tonsillitis

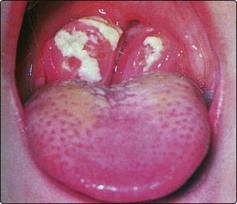

Acute tonsillitis presents a quite different clinical picture. The child is systemically unwell, there is dysphagia, halitosis, pyrexia, together with cervical lymphadenopathy. The diagnosis is apparent from the appearance of the tonsils (Fig. 3.48). Rare disorders that give a similar appearance may need to be excluded. Diphtheria (usually the tonsil is covered by a membrane) and haematological disorders should be included in the differential diagnosis. Throat swabs are generally unhelpful in management as the most common organism isolated is Streptococcus.

Treatment of acute tonsillitis is with bed rest and administration of antibiotics such as penicillin, with maybe the first dose parenterally. Maintenance of fluid intake is important, and paracetamol provides suitable analgesia and acts as an antipyretic in lowering the temperature. Symptoms usually resolve within a few days. Tonsillectomy may be recommended in patients with severe recurrent infections (p. 74). Complications of tonsillitis are infrequent, but spread of infection may lead to abscess formation in the peritonsillar, retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal spaces (Fig. 3.49).

Infectious mononucleosis

Sore throats

Most acute sore throats are viral in origin.

Most acute sore throats are viral in origin.

Bacterial tonsillitis is easily diagnosed by looking at the tonsils.

Bacterial tonsillitis is easily diagnosed by looking at the tonsils.

Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy) is rare in children.

Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy) is rare in children.

Antibiotics only shorten the course of a true bacterial tonsillitis.

Antibiotics only shorten the course of a true bacterial tonsillitis.

An ulcerative tonsillitis may be caused by an underlying blood disorder.

An ulcerative tonsillitis may be caused by an underlying blood disorder.

Exclude neoplasia in any adult with a chronic sore throat.

Exclude neoplasia in any adult with a chronic sore throat.

Think of infectious mononucleosis in teenagers, particularly if the tonsils are covered with a membranous exudate.

Think of infectious mononucleosis in teenagers, particularly if the tonsils are covered with a membranous exudate.

Tonsillectomy and adenoidal conditions

Tonsillectomy

Indications

The indications for tonsillectomy are controversial (Table 3.13). Recurrent tonsillitis is probably the least controversial indication, as any child having more than three or four attacks a year may be spending upwards of 1–2 months off school every year. Chronic tonsillitis is not a straightforward diagnosis, and some would dispute it as a cause of a chronic sore throat in adults. Tonsillectomy for peritonsillar abscess (quinsy) is only recommended if there is a past history of recurrent tonsillitis. The tonsils are usually symmetrical so that tonsillectomy for unilateral enlargement is necessary if a diagnosis of neoplasia is being entertained. More recently it has become apparent that the tonsils, usually in association with the adenoids in children and the uvulopalatal area in adults, may be a cause of snoring and the more sinister obstructive sleep apnoea. In such cases tonsillectomy may be advised, in combination with adenoidectomy and palatal surgery as appropriate (p. 80). Tonsillar biopsy is also used as a screening test for new-variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.

Table 3.13 Tonsillectomy: indications and contraindications

Contraindications

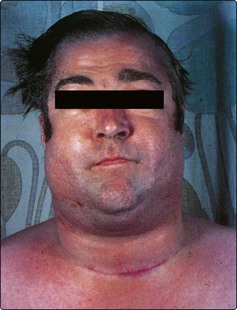

Contraindications to tonsillectomy are summarized in Table 3.13. The major operative risk is haemorrhagic so that any bleeding disorder should be corrected before surgery or permanent deferral may be necessary. Any recent inflammation will result in greater haemorrhage, so tonsillectomy should be avoided for 2–3 weeks after an acute infection. A child weighing less than 15 kg has a greater risk attached to the hazards of blood loss. In such cases the indications for surgery should be clear-cut and strong. Equally, a grossly overweight patient should be placed on a sensible weight-reduction diet before reconsidering tonsillectomy or any other elective surgical procedure.

The adenoids

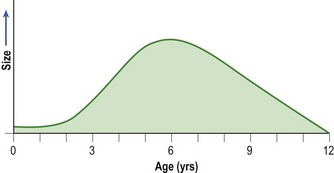

The adenoid is a collection of lymphoid tissue in the postnasal space (see Fig. 3.3, p. 56). Patients may attribute many symptoms to this structure, e.g. anosmia, malaise and nasal obstruction. Owing to their site, adenoids in children may obstruct the Eustachian tube and may be associated with otitis media with effusion (OME) (pp. 6 and 13). Adenoidal hypertrophy is a cause of childhood nasal obstruction and discharge. The adenoid also appears to play an important role, together with the tonsils, in producing nocturnal airway narrowing, which may result in obstructive sleep apnoea (p. 80).

The adenoid tends to hypertrophy up to the age of 6 years and then gradually regresses to an insignificant size by the age of about 12. Hence, pathology due to adenoidal disease is maximal by the age of 6 years (Fig. 3.50). Adults developing symptoms of adenoidal hypertrophy should have the nasopharynx examined to exclude malignancy.

Signs and investigations of adenoidal disease

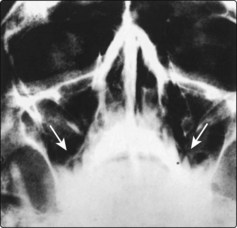

In children a paediatric flexible nasal endoscope is the most reliable way to assess the state of the adenoids. Where this is not available, a lateral X-ray of the nasopharynx may be helpful (Fig. 3.52). However, in most cases a clinical assessment of relevant symptoms is sufficient to consider adenoidectomy, and the size is assessed under general anaesthesia by finger palpation of the postnasal space or a postnasal space mirror.

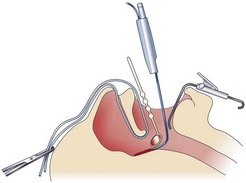

Adenoidectomy

The indications and contraindications to adenoidectomy are summarized in Table 3.14. Traditionally, adenoids are curetted under general anaesthesia, a blind technique which may leave residual adenoidal tissue. Increasingly, adenoidectomy is performed, under vision, using a postnasal space mirror and suction diathermy ablation (Fig. 3.53). The postoperative care is similar to a child undergoing tonsillectomy.

Table 3.14 Adenoidectomy: indications and contraindications

Tonsillectomy and adenoidal conditions

Asymmetry in size of tonsils may be an indication for tonsillectomy.

Asymmetry in size of tonsils may be an indication for tonsillectomy.

Tonsillectomy carries a risk of mortality, albeit very low.

Tonsillectomy carries a risk of mortality, albeit very low.

Postoperative nursing care should be by suitably trained staff.

Postoperative nursing care should be by suitably trained staff.

Reactionary haemorrhage in the first 24 hours carries the greatest risk of morbidity and mortality.

Reactionary haemorrhage in the first 24 hours carries the greatest risk of morbidity and mortality.

Tonsillectomy may fail if performed for the wrong indication, or if the tonsils are not removed in toto.

Tonsillectomy may fail if performed for the wrong indication, or if the tonsils are not removed in toto.

Symptoms due to adenoidal disease are maximal at about 6 years of age.

Symptoms due to adenoidal disease are maximal at about 6 years of age.

Secretory otitis media is frequently caused by Eustachian tube dysfunction secondary to adenoidal hypertrophy.

Secretory otitis media is frequently caused by Eustachian tube dysfunction secondary to adenoidal hypertrophy.

Obstructive sleep apnoea and snoring in children are commonly due to both tonsils and adenoids causing airway narrowing.

Obstructive sleep apnoea and snoring in children are commonly due to both tonsils and adenoids causing airway narrowing.

Hypernasality is a severe handicap and may result if adenoidectomy is performed in children with a short or cleft palate.

Hypernasality is a severe handicap and may result if adenoidectomy is performed in children with a short or cleft palate.

Adenoid symptoms in adults are likely to be due to a postnasal space tumour.

Adenoid symptoms in adults are likely to be due to a postnasal space tumour.

Dysphagia

Clinical features

Pharyngo-oesophageal lesions may give rise to a feeling of something in the throat, prior to the development of true dysphagia. Patients with persistence of such a sensation, particularly if associated with certain cardinal features, require full investigation (Fig. 3.54). Lesions in the mouth or oropharynx give a feeling of swallowing over an object, but oesophageal pathology leads to sticking of food. The duration of symptoms is important, with a progressive dysphagia being highly significant. Neurological disorders generally produce greater difficulty with swallowing liquids than solid food.

Examination

A full ENT examination is mandatory, but special attention is directed to the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx. The simple action of asking the patient to open the mouth may reveal an obvious lesion (Fig. 3.55). With a mirror or flexible rhinolaryngoscope it is possible to visualize down to the laryngopharynx, which may show pooling saliva or a vocal cord paralysis. Careful palpation of any local lesion and the neck is essential.

Investigations

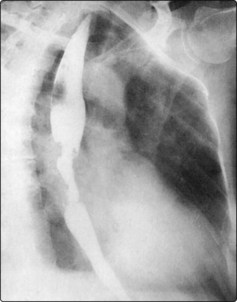

The principal investigation is a barium swallow, which outlines the hypopharynx, oesophagus and stomach (Fig. 3.56). A plain lateral X-ray of the neck may reveal shadowing due to neoplasia of the posterior pharyngeal wall. In persistent dysphagia, even with normal radiological tests, a pharyngo-oesophagoscopy is mandatory. Any abnormal lesion must be biopsied.

Acute dysphagia

Acute dysphagia is very common and can be due to inflammatory conditions such as tonsillitis (p. 72) or aphthous ulceration (p. 82). Other causes include swallowed foreign bodies or the ingestion of caustic liquids. A diagnosis of the aetiology is made relatively easily from the history.

Chronic dysphagia

Patients with chronic dysphagia require an in-depth history and examination as already discussed. The causes of chronic dysphagia are listed in Table 3.15.

| Type | Cause |

|---|---|

| Neuromuscular disorders | Motor neurone disease, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis |

| Intrinsic lesions | Neoplasia, pharyngeal pouch, strictures, achalasia |

| Extrinsic lesion | Thyroid enlargement, aortic aneurysm |

| Systemic causes | Scleroderma (rare) |

| Psychosomatic | Globus pharyngeus |

Intrinsic lesions of the digestive tract

Neoplasia

Neoplasia of the pharyngo-oesophagus is a frequent cause of dysphagia and is invariably associated with other cardinal features (Fig. 3.54; see also p. 106). The common sites affected are the piriform fossa, postcricoid region and the oesophagus. The majority of cases will require radiotherapy and salvage surgery. The resected portion of the pharyngo-oesophagus can be replaced by either a portion of jejunum or the stomach pulled into the defect and anastomosed to the superior resection margin. In some cases the larynx is also removed so that the patient breathes through the trachea, which is relocated to the anterior neck.

Pharyngeal pouch

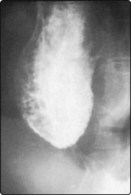

A pharyngeal pouch is a hernia of the pharyngeal mucosa through a potential weakness (Killian’s dehiscence) between the upper thyropharyngeus and lower cricopharyngeus fibres of the inferior constrictor muscle. Food debris collects in the pouch, which enlarges progressively. Regurgitation of undigested food particles is common and overspill may result in a chronic cough and pneumonitis. The pouch may increase in size to such an extent that it compresses the oesophagus to cause dysphagia. A barium swallow is usually diagnostic (Fig. 3.57). All but the smallest pouches will require either surgical excision and cricopharyngeal myotomy through the neck, or endoscopic stapling and division of the party wall between the pharynx and oesophagus.

Oesophageal stricture

Strictures of the oesophagus may be due to malignancy or secondary to fibrosis induced by chronic reflux oesophagitis associated with a hiatus hernia. It is important to fully investigate all strictures with biopsy, to exclude neoplasia. Inflammatory strictures producing dysphagia are invariably accompanied by a long history of heartburn and epigastric discomfort. The typical stricture due to oesophageal reflux is seen in the lower third of the oesophagus (Fig. 3.58). Treatment comprises aggressive medical therapy to counteract the acid reflux, and possible dilatation of the stricture. Failure of conservative measures in patients with severe symptoms will necessitate surgical correction.

Achalasia of the oesophagus

Achalasia of the oesophagus is caused by a failure of relaxation of the cardia and abnormal oesophageal muscular tone during swallowing. This results in a stricture at the defective site, with gross proximal dilatation of the oesophagus. Besides dysphagia, regurgitation is common. A barium swallow has a typical appearance (Fig. 3.59). The majority of patients will require a cardiomyotomy (Heller’s operation) to divide the cardiac sphincter, as dilatation with bougies frequently fails to produce satisfactory relief.

Extrinsic lesions

The thyroid gland may narrow the oesophagus, either by compression in benign pathology, or by direct invasion in cases of malignancy. Vascular compression of the oesophagus can be produced by an aortic aneurysm or an aberrant right subclavian artery (dysphagia lusoria) (Fig. 3.60).

Psychosomatic causes

Dysphagia

A persistent feeling of something in the throat requires full investigation.

A persistent feeling of something in the throat requires full investigation.

Insist on establishing beyond doubt that a patient has true dysphagia.

Insist on establishing beyond doubt that a patient has true dysphagia.

Always ask about the cardinal associated symptoms.

Always ask about the cardinal associated symptoms.

Acute dysphagia is usually inflammatory in origin, but exclude a foreign body, particularly in children.

Acute dysphagia is usually inflammatory in origin, but exclude a foreign body, particularly in children.

All cases of chronic dysphagia require endoscopy, even in the presence of a normal barium swallow.

All cases of chronic dysphagia require endoscopy, even in the presence of a normal barium swallow.

Neurological causes of dysphagia are notoriously difficult to manage.

Neurological causes of dysphagia are notoriously difficult to manage.

Ensure that benign oesophageal strictures are truly benign by biopsy.

Ensure that benign oesophageal strictures are truly benign by biopsy.

Many persistent cases of globus pharyngeus will require barium swallow and endoscopy.

Many persistent cases of globus pharyngeus will require barium swallow and endoscopy.

A trial of therapy to neutralize or decrease gastric secretions may benefit patients with a globus pharyngeus.

A trial of therapy to neutralize or decrease gastric secretions may benefit patients with a globus pharyngeus.

Salivary glands

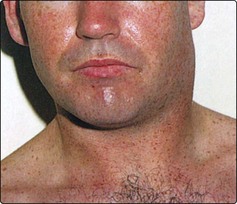

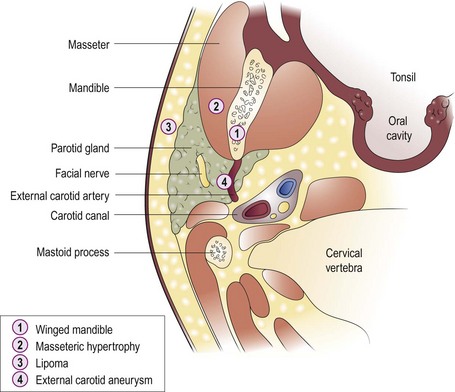

Pathology of the major salivary glands, the parotids and submandibular glands, will usually present as a swelling which may be associated with pain. It is important to establish the characteristics of any swelling, particularly to note whether it is intermittent, constant or progressive. Most causes of salivary disease producing pain are exacerbated by chewing. The major salivary glands are anatomically closely associated with lymph nodes, so non-salivary gland pathology may mimic salivary gland disease. It is important to appreciate that enlargement of the deep lobe of the parotid gland may cause swelling in the tonsil region which may not be visible or palpable in the neck (Fig. 3.61).

Minor salivary glands are located in the oral cavity and palate. In the mouth they frequently cause salivary retention cysts (p. 83).

Parotid gland

Swelling

The parotid gland territory is more extensive than most clinicians appreciate. Parotomegaly can affect the gland diffusely, or be localized to one area (Table 3.16). Extraparotid disease may present as parotid lumps (Fig. 3.61). A unilateral localized swelling is invariably neoplastic, of which 90% will be benign pleomorphic adenomas. Malignant parotid tumours are frequently accompanied by pain and facial nerve paresis, in addition to parotomegaly (see p. 113).

| Symptoms | Cause |

|---|---|

| Swelling | Extraparotid (Fig. 3.61) |

| Parotid | |

| – neoplasia | |

| – Sjögren’s | |

| – sarcoidosis | |

| – systemic diseases | |

| – drugs | |

| Swelling and pain | Mumps parotitis |

| Bacterial parotitis | |

| Sialectasis | |

| Neoplasia | |

| Calculus |

Swelling and pain

Mumps

This used to be the most common cause of bilateral parotid swelling until the introduction of vaccination programmes (Fig. 3.62). Mumps-related parotomegaly is tender to touch and there is usually trismus and pyrexia. Treatment is symptomatic unless a bacterial infection supervenes to produce suppuration. Rare complications of mumps infection include orchitis and sensorineural deafness.

Neoplasia

Neoplasia, particularly if malignant, presents with parotid pain and swelling (p. 112). Secondary bacterial infection may produce features of a parotitis. The facial nerve is commonly affected, and there may be skin tethering (Fig. 3.63).

Submandibular gland

Swelling

Painless diffuse enlargement of the submandibular gland is infrequent. In such cases, neoplasia should be excluded (Table 3.18).

Table 3.18 Causes of swelling and pain of the submandibular gland

| Symptoms | Cause |

|---|---|

| Swelling | Neoplasia |

| Swelling and pain | Intraoral disease causing lymph-node involvement (giving rise to these symptoms in the submandibular region) |

| Calculus | |

| Neoplasia |

Swelling and pain

Submandibular calculi

The most common primary disease of the submandibular gland causing pain and swelling is calculi. The symptoms are typically related to meal times. Usually the distal part of the duct is blocked so that many calculi are palpable in the floor of the mouth. Most stones are radio-opaque (Fig. 3.64). If located in the mouth they can be removed by an intraoral approach. More proximally sited calculi require excision of the gland.

Neoplasia

Salivary glands

One of the most common causes of bilateral parotid swelling is mumps parotitis.

One of the most common causes of bilateral parotid swelling is mumps parotitis.

An acute unilateral diffuse swelling of the parotid is nearly always a bacterial parotitis.

An acute unilateral diffuse swelling of the parotid is nearly always a bacterial parotitis.

Localized parotid swellings may be neoplastic.

Localized parotid swellings may be neoplastic.

The majority of neoplastic parotid swellings are benign.

The majority of neoplastic parotid swellings are benign.

Progressive pain, skin tethering and facial nerve involvement are indicative of a malignant parotid lesion.

Progressive pain, skin tethering and facial nerve involvement are indicative of a malignant parotid lesion.

The most common cause of swelling and pain in the region of the submandibular gland is intraoral disease.

The most common cause of swelling and pain in the region of the submandibular gland is intraoral disease.

Submandibular calculi are the most common cause of recurrent pain and swelling of the submandibular gland.

Submandibular calculi are the most common cause of recurrent pain and swelling of the submandibular gland.

Localized swellings of the submandibular gland, with or without pain, should be assumed to be malignant until proven to the contrary.

Localized swellings of the submandibular gland, with or without pain, should be assumed to be malignant until proven to the contrary.

Snoring and sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea may be secondary to three situations:

Central sleep apnoea, the most uncommon, is due to a defect in the respiratory drive centre in the brainstem.

Central sleep apnoea, the most uncommon, is due to a defect in the respiratory drive centre in the brainstem.

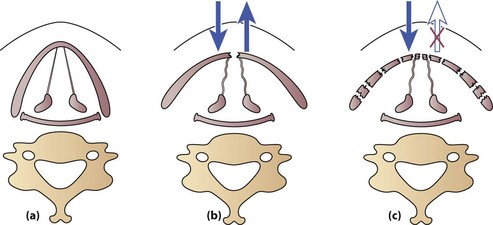

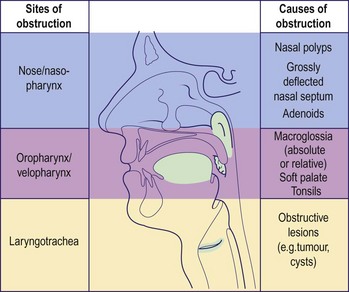

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) frequently presents to the ENT department, either labelled as snoring or sometimes snoring with apnoea. In OSA, unlike central sleep apnoea, there are chest movements and a struggle to shift air, but without success. The site of the airway obstruction in OSA may be nasal, pharyngeal or laryngotracheal (Fig. 3.65).

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) frequently presents to the ENT department, either labelled as snoring or sometimes snoring with apnoea. In OSA, unlike central sleep apnoea, there are chest movements and a struggle to shift air, but without success. The site of the airway obstruction in OSA may be nasal, pharyngeal or laryngotracheal (Fig. 3.65).

Mixed-type sleep apnoea has manifestations of both the central and obstructive types.

Mixed-type sleep apnoea has manifestations of both the central and obstructive types.

Fig. 3.65 Potential sites and causes of narrowing that may result in snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea.

Potential complications

Potential complications of OSA are summarized in Table 3.19. A partial airway obstruction, producing snoring or a full-blown apnoeic episode, causes oxygen desaturation. If this continues long term, it may result in a pulmonary hypertension, eventually leading to right ventricular failure and cor pulmonale.

Table 3.19 Potential complications of obstructive sleep apnoea

| Type | Complication |

|---|---|

| Cardiac | Raised pulmonary artery pressure |

| Pulmonary hypertension | |

| Cor pulmonale | |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | |

| CNS | Hypersomnolence |

| Lethargy | |

| Reduced concentration and memory | |

| General | Sudden infant death syndrome (cot death) |

| Failure to thrive (children) |

Investigations

Rhinolaryngoscopy

Passage of a flexible rhinolaryngoscope (Fig. 3.66) allows a full examination of the upper respiratory tract to identify any obstructive pathology. It can also be used to observe whether the velopharyngeal lumen is compromised as a patient recovers from a short anaesthetic which mimics sleep nasendoscopy. A forced negative Valsalva manoeuvre (Müller manoeuvre) with visualization of the velopharynx also provides a measure of potential narrowing in this region.

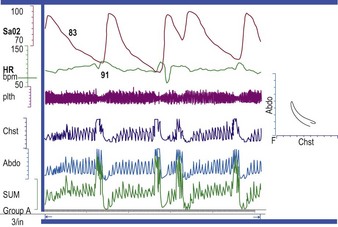

Sleep studies

The routine investigations may be inconclusive, and a satisfactory screening evaluation should include a sleep study. During the sleep study it is possible to measure the following parameters (Fig. 3.67):

cutaneous oxygen saturation levels to detect any hypoxic dips

cutaneous oxygen saturation levels to detect any hypoxic dips

electrocardiogram (ECG) monitors to assess the presence of arrhythmias and other cardiac abnormalities during periods of hypoxia

electrocardiogram (ECG) monitors to assess the presence of arrhythmias and other cardiac abnormalities during periods of hypoxia

air movement with nasal thermistors or by direct observation

air movement with nasal thermistors or by direct observation

chest wall and abdominal movements detected by strain gauges.

chest wall and abdominal movements detected by strain gauges.

Management of obstructive sleep apnoea

Surgery

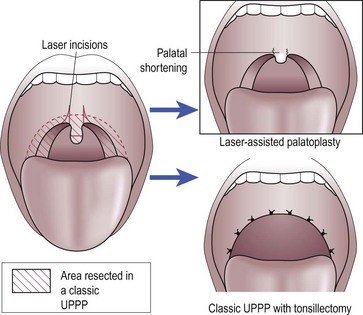

In adults, nasal surgery may be required for nasal polyposis or a deflected septum. The velopharyngeal isthmus is also often the site of narrowing, and this is corrected by either a laser-assisted palatoplasty (LAPP) or a uvulopharyngopalatoplasty (UPPP) with a tonsillectomy (Fig. 3.68). The results of these procedures on snoring and sleep apnoea are variable. Some patients may be candidates for hyoid and jaw surgery to correct obstruction at other levels. In extreme cases of OSA, a tracheostomy may be life saving, as it provides a bypass to any obstruction.

Fig. 3.68 Surgical options for shortening and stiffening the palate in snoring and upper airway obstruction.

Snoring and sleep apnoea

Snoring may not be a trivial noise.

Snoring may not be a trivial noise.

Sleep apnoea may be central, obstructive or mixed.

Sleep apnoea may be central, obstructive or mixed.

OSA is always associated with snoring.

OSA is always associated with snoring.

Patients with OSA manifest a struggle during episodes of apnoea.

Patients with OSA manifest a struggle during episodes of apnoea.

Persistent sleep apnoea may result in serious cardiac and central nervous system complications.

Persistent sleep apnoea may result in serious cardiac and central nervous system complications.

A sleep study is a useful screening procedure, both in snorers and in patients with suspected sleep apnoea.

A sleep study is a useful screening procedure, both in snorers and in patients with suspected sleep apnoea.

Adenotonsillectomy is all that is required to cure the majority of children with OSA.

Adenotonsillectomy is all that is required to cure the majority of children with OSA.

Oral cavity

The symptoms and signs of oral disease have already been covered (p. 58). Most lesions will either be visible to both patient and clinician, or be easily palpable. The most common intraoral pathologies are dental caries and periodontal disease.

Congenital and developmental anomalies

Congenital and developmental anomalies are not uncommon in the oral cavity. Abnormal development of the frenulum may result in tongue-tie (ankyloglossia). If it interferes with articulation, which is extremely rare, it can be freed surgically. Macroglossia is usually seen in association with Down’s syndrome. However, it is also a feature of acromegaly. Vascular and lymph-vessel abnormalities can result in macroglossia (Fig. 3.69).

Ulceration in the oral cavity

Recurrent oral ulceration

Recurrent ulceration is the most common cause of ulcers in the oral cavity. It may be due to aphthous ulceration which is of unknown aetiology, although nutritional and hormonal factors, as well as minor trauma, have been implicated. Herpes simplex eruptions have similar clinical features, although are more likely to involve the hard palate. Some patients with recurrent oral ulceration may have underlying vitamin B, folic acid or iron deficiencies. The lesions usually commence as a small vesicle which rapidly progresses to form ulcers. They may be of any size and number and occur anywhere in the mouth (Fig. 3.70). There is severe pain and the ulcers resolve spontaneously after 2–3 weeks. Various steroid preparations as pastes or pellets may be used orally to treat ulcers. Mouthwashes containing antibiotics or antiseptics give some pain relief, e.g. phenol gargles. Treatment with aciclovir may be employed in ulcers of herpetic origin.

White lesions in the oral cavity

The three most common white lesions in the mouth are:

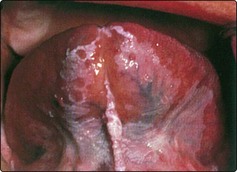

Lichen planus may be clinically and histologically difficult to distinguish from leukoplakia (Fig. 3.71). Both can occur anywhere in the oral cavity, although lichen planus may be associated with a variable degree of pain. Biopsy is essential to differentiate the two lesions and also to exclude the presence of malignancy in cases of leukoplakia. Between 3 and 5% of leukoplakic plaques are premalignant and this is more likely in females who smoke.

Cystic lesions in the oral cavity

Retention cysts

Retention cysts can occur owing to duct blockage of a minor salivary gland. They can reach considerable sizes, particularly if located in the floor of the mouth, when the term ‘ranula’ is applied (Fig. 3.72). A localized lymphangioma has an identical appearance.

Miscellaneous lesions in the oral cavity

Fissured tongue

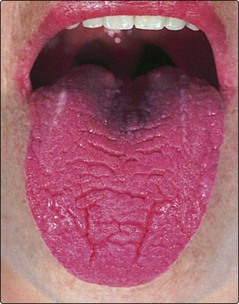

A fissured tongue is frequently a congenital condition (Fig. 3.73). On rare occasions it is associated with iron-deficiency anaemia. Most cases are asymptomatic, but if food debris collects in the grooves it may give rise to soreness and halitosis. This is easily managed by regular oral hygiene.

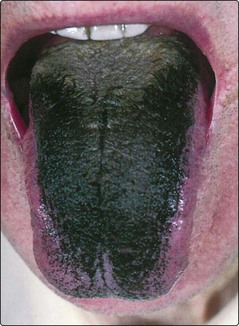

Black hairy tongue

A black hairy tongue is caused by an overgrowth of filiform papillae on the dorsum (Fig. 3.74). Most sufferers are tobacco smokers and some cases have followed local application of antibiotics. The papillae may reach 1 cm in length and are treated by scraping and daily application of a toothbrush to the tongue.

Intraoral lumps

Oral cavity

All lesions in the oral cavity, visible or not, should be palpated.

All lesions in the oral cavity, visible or not, should be palpated.

Lesions in the mouth may be due to local or systemic disease.

Lesions in the mouth may be due to local or systemic disease.

Lichen planus and leukoplakia may look identical.

Lichen planus and leukoplakia may look identical.

Leukoplakia may be premalignant and therefore should be biopsied.

Leukoplakia may be premalignant and therefore should be biopsied.

All persistent ulcers and any non-ulcerating masses should be biopsied to exclude neoplasia.

All persistent ulcers and any non-ulcerating masses should be biopsied to exclude neoplasia.

Foreign bodies

Inhaled foreign bodies

Over 75% of patients presenting with inhaled foreign bodies are children aged 4 years or under. The features of foreign body inhalation are dependent on its type and location in the laryngotracheobronchial tree. Vegetable material, e.g. peanuts, seeds and popcorn, produces a severe mucosal reaction in comparison to inorganic material, e.g. coins and buttons. Impaction in the larynx may be rapidly fatal owing to complete respiratory obstruction. The Heimlich manoeuvre may dislodge the object and should be attempted. In other circumstances an alternative airway should be secured (p. 66) and the foreign body removed endoscopically.

Swallowed foreign bodies

The variety of swallowed foreign bodies is legion (Fig. 3.76). However, the majority are coins, fish bones, meat bones and lumps of meat. Children often swallow a handful of coins at a time. In adults, ingestion of foreign bodies is more likely if the patient uses dentures. These prevent adequate chewing and with a full upper plate there is some sensory deprivation.

Sites of impaction

Fish bones tend to lodge in the oropharynx (posterior tongue, vallecula and tonsil). Most other foreign bodies will tend to impact at sites of narrowing of the pharyngo-oesophagus (Fig. 3.77). These are the piriform fossa and postcricoid region, particularly at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle. The aorta and left main bronchus constrict the mid-oesophagus and there is a relatively reduced diameter at the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Visualization of foreign bodies

Most foreign bodies in the mouth and pharynx can be identified with the use of a head mirror and routine instruments, e.g. tongue depressors and laryngeal mirrors. The specific sites outlined in Figure 3.77 should be inspected. Fish bones frequently lodge in the tonsil and only a tiny length may project above the surface lining.

An oesophageal foreign body will be out of sight to routine examination, but commonly is associated with pooling of saliva in the piriform fossae. X-rays may be unhelpful because only radio-opaque objects will be visualized (Fig. 3.78), but soft tissue changes can be indicative.

Management after pharyngo-oesophagoscopy

Oesophageal rupture

In all pharyngo-oesophageal endoscopies there is a risk of perforating the lumen. The cardinal features of an oesophageal rupture are shown in Table 3.20, and are due to food, bacteria and digestive juices contaminating the periluminal areas. The precise combination of clinical features is dependent on whether the perforation is in the cervical or thoracic oesophagus. Cardiorespiratory features predominate in the latter site.

Treatment of oesophageal rupture

Foreign bodies

Inhaled foreign bodies lodged in the larynx may be immediately fatal.

Inhaled foreign bodies lodged in the larynx may be immediately fatal.

Cough and wheezing developing in a previously well child should alert the clinician to the presence of an inhaled foreign body.

Cough and wheezing developing in a previously well child should alert the clinician to the presence of an inhaled foreign body.

A time lapse of days to months may occur between inhalation of foreign bodies and clinical symptoms: dependent on the nature of the object, i.e. vegetable or non-vegetable.

A time lapse of days to months may occur between inhalation of foreign bodies and clinical symptoms: dependent on the nature of the object, i.e. vegetable or non-vegetable.

Swallowed foreign bodies located in the mouth and pharynx generally produce ipsilateral symptoms.

Swallowed foreign bodies located in the mouth and pharynx generally produce ipsilateral symptoms.

Oesophageal foreign bodies are usually localized in the midline.

Oesophageal foreign bodies are usually localized in the midline.

A good headlight, simple instruments and angled forceps will enable most foreign bodies in the mouth and pharynx to be removed.

A good headlight, simple instruments and angled forceps will enable most foreign bodies in the mouth and pharynx to be removed.

Solid impacted oesophageal foreign bodies may pass spontaneously.

Solid impacted oesophageal foreign bodies may pass spontaneously.

Exclude underlying pathology in foreign bodies impacted in the oesophagus.

Exclude underlying pathology in foreign bodies impacted in the oesophagus.

Educate all medical and nursing staff in the features of a pharyngo-oesophageal perforation after endoscopic examination.

Educate all medical and nursing staff in the features of a pharyngo-oesophageal perforation after endoscopic examination.

ENT aspects of HIV infection

Clinical features

WHO stages 2 and 3 include a group of symptoms and infections previously included in a stage of the disease described as AIDS-related complex (ARC). Neoplasias are absent but symptoms include malaise, fevers and night sweats, weight loss and unexplained diarrhoea. Many of the clinical signs of ARC may present as ENT manifestations (Table 3.21).

Table 3.21 Clinical signs of AIDS-related complex (ARC)

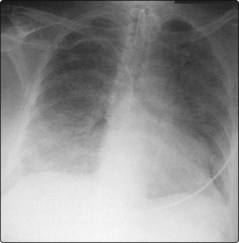

Full-blown AIDS (WHO stage 4)

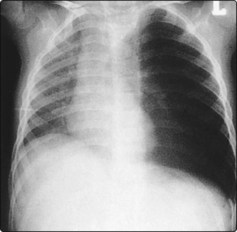

The diagnosis of AIDS is based on the presence of AIDS-defining illnesses, which include opportunistic infections and tumours indicative of cellular immune deficiency in individuals with no known cause for immune deficiency. The classic opportunistic infection is in the lungs and is caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci (Fig. 3.80). Candidal infection of the mouth and extending into the oesophagus is not infrequent, and results in severe dysphagia. Rhinosinusitis, causing postnasal discharge and sinofacial discomfort, is very common. PGL affecting lymphoid tissue in the nasopharynx can cause blockage of the Eustachian tube and subsequent secretory otitis media. Intraoral ulceration in AIDS may be due to herpes virus infection. It is similar in appearance to the usual benign variety, but does not resolve spontaneously. Of the neoplasias, the most common is Kaposi’s sarcoma. These appear as small, bluish, painless skin lesions, and the head, neck and oral cavity may be involved (Figs 3.81 and 3.82). Other tumours include non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B-cell type) and squamous cell carcinoma. Parotid enlargement can be an early presenting sign of HIV disease and is usually due to cystic change.