Chapter 11 The theoretical basis for evidence-based neurological physiotherapy

Introduction

This chapter aims to explain the theoretical framework underlying current practice in neurological physiotherapy for adults with damage to the nervous system. The text below will explain why theory and evidence-based practice are important, clarify the role of the neurological physiotherapist and discuss the key neurophysiological, motor learning and behavioural principles that guide practice. These guiding principles are derived from the theoretical framework proposed by Lennon and Bassile (2009).

Why are theory and evidence-based practice important?

Therapists need to subscribe to a theoretical framework for intervention, as theory provides the explanation not only for the behaviour of people following neurological damage, but also for the actions and decisions of therapists in clinical practice (Shephard, 1991). There are several neurological treatment approaches that influence the content, structure and aims of therapy. In the past therapists may have implemented care based on their preferred treatment approaches. However, to date there is no evidence to suggest that one therapy approach is superior to another (Kollen et al., 2009; Pollock et al., 2007). Therapy delivered in practice is always composed of multiple components tailored to suit each individual patient; therefore, research trials should aim to evaluate the active ingredients or components within physiotherapy, as similarities between approaches may actually outweigh their differences. In order to implement evidence-based practice, therapists are expected to incorporate a wide range of strategies that are supported by the current evidence base into their treatment programmes (Pollock et al., 2007).

There are many examples of specific training strategies such as strength training or task-specific practice, which are effective at improving movement and function (Van Peppen et al., 2007 see www.cochrane.org for relevant systematic reviews). There are also many clinical guidelines that provide a comprehensive review of all the available evidence to date for multidisciplinary management of people post-stroke (NCGS, 2008), with Parkinson’s disease (Keus et al., 2006) and with multiple sclerosis (MS Society, 2008). These guidelines, developed by multidisciplinary panels and subjected to peer review, and are based on the best available evidence.

Components selected within therapy sessions should be evidence-based rather than based on therapist preference for a specific treatment approach. However, it is also important to realize that there are still many key areas of clinical practice with no evidence or conflicting evidence; therefore, therapists continue to rely on their clinical reasoning skills to select treatment techniques appropriate to the needs, wishes and goals of patients and their carers. This is why evidence-based practice is defined as the integration of best evidence with clinical expertise and patient values (Bernhardt & Legg, 2009).

Evidence-based guidelines rather than therapist preference for any named therapy approach should serve as a framework from which therapists should derive the most effective treatment (Kollen et al., 2009). However, there are many methodological shortcomings in the current evidence base and further high-quality trials need to be conducted (Kollen et al., 2009).

Role of the physiotherapist

Physiotherapists help patients, their carers and the multidisciplinary team to identify potential for change following damage to the nervous system. Physiotherapists provide stimulus via movement to engage patient response; physiotherapists make movement and activity possible by using a variety of strategies such as therapeutic handling, or elimination of gravity and activity in mid range to elicit motor activity even when patients are unable to demonstrate movement to command (Kilbride & Cassidy, 2009).

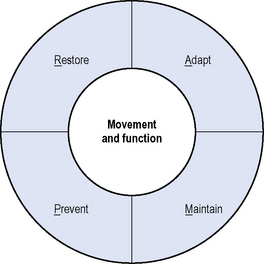

The aims of neurological physiotherapy can be summed up using the acronym RAMP for Recovery, Adaptation, Maintenance and Prevention (see Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 RAMP – aims of neurological physiotherapy.

(Reproduced from Lennon S, Bassile C. Guiding Principles for neurological physiotherapy. In Lennon S, Stokes M (eds). Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. Elsevier Ltd, London, 2009, pp. 97-111, with permission from Elsevier Ltd.)

Physiotherapy ideally aims to restore movement and function in people with neurological pathology, but this may not always be possible. Adaptation (compensation) refers to the use of alternative movement strategies to complete a task (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott, 2007, pp. 152–153). Therapists focus on promoting compensatory strategies that are necessary for function and discouraging those that may be detrimental to the patient, e.g. promoting musculoskeletal damage, such as knee hyperextension (Edwards, 2002, p. 2). Interventions aimed at recovery of function need to be emphasized over compensation if the patient has the potential to change. Maintenance of function is just as important as recovery, and should be viewed as a positive achievement; several reviews have now confirmed that functional ability can be maintained despite deteriorating impairments in progressive neurological disease (Keus et al., 2006). Physiotherapy also aims to prevent the development of complications such as contracture, swelling and disuse atrophy. There are different stages in patient management, where these aims may have differential priorities. Understanding the nature of the pathology, and the prognosis for recovery in collaboration with patients and care givers to establish desired goals will help determine which of these aims should be emphasized in physiotherapy.

Guiding principles

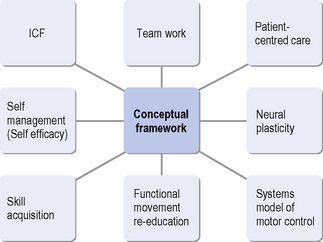

Lennon and Bassile (2009) have identified eight principles to guide physiotherapy practice (see Figure 11.2): (1) the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); (2) team work; (3) patient-centred care; (4) neural plasticity; (5) a systems model of motor control; (6) functional movement re-education; (7) skill acquisition; and (8) self-management (self-efficacy). Each of these principles will be discussed in this chapter.

Figure 11.2 Guiding principles for neurological physiotherapy.

(Reproduced from Lennon S, Bassile C. Guiding Principles for neurological physiotherapy. In: Lennon S, Stokes M, eds. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. Elsevier Ltd, London, 2009, pp. 97-111, with permission from Elsevier Ltd.)

Principle 1: The ICF

The WHO has developed the ICF (2001; www.who.int/classifications/icf), which provides a systematic way of understanding the problems faced by patients, illustrating the multiple levels at which therapy may act. The activities dimension covers the range of activities performed by an individual. The participation dimension classifies the areas of life in which there are societal opportunities or barriers for each individual.

Within the ICF framework, neurological physiotherapy may directly target both impairment (a loss or abnormality of body structure) and activity (performance in functional activities) with the overall aim of improving quality of life and enabling participation in desired life roles. Most large randomized controlled trials agree that patients need to have a minimum level of residual movement to demonstrate functional improvement (Van Peppen et al., 2004). This means that therapists will need to use both impairment and function focused strategies depending on the patient.

Principle 2: Team work

Neurological physiotherapists use their clinical reasoning skills combined with current evidence to assess, develop and evaluate an appropriate plan of care in collaboration with the patients and their carers, and the multidisciplinary team (Ryerson, 2009).

Team work is required to coordinate rehabilitation, as a variety of health-care professionals are involved to exchange information with the patients and their families. Team meetings are held to agree a common plan of care in order to reduce the risk of conflicting information, and to work towards common goals (Sivaraman Nair & Wade, 2003). Interdisciplinary rehabilitation refers to the activities of the health-care team, where there is a high level of communication, mutual goal planning and evaluation (Long et al., 2003). The Stroke Unit Trialists Collaboration (SUTC, 2006) has identified that patients who receive organized stroke unit care provided in hospital by nurses, doctors and therapists who specialize in looking after stroke patients and work as a coordinated team are more likely to survive their stroke, return home and become independent in looking after themselves. Thus it would appear that team working is an essential factor in improving patient outcomes.

Goal setting

Developing an appropriate plan of care revolves around collaborative goal setting within the team. Setting goals by the interdisciplinary team is recognized as a core component of neurorehabilitation (Wade, 2009). Setting goals aims to:

Although there is limited evidence as to the best approach to use in goal setting, there is strong evidence that prescribed, specific and challenging goals lead to improved patient performance on simple cognitive and motor tasks (see Levack et al., 2006, for a review of goal planning in rehabilitation). Team goals need to be based on patient’s wishes, expectations, priorities and values in line with the SMART acronym, which recommends that goals should be specific, measurable, achievable/ambitious, relevant and timed (Playford et al., 2009). Also see Bovend’Eerdt et al. (2009) for some practical guidance on how to set SMART goals.

Principle 3: Patient-centred care

Patient and carer involvement is a key component of neurological rehabilitation (Cott et al., 2007; Laverty et al., 2009). There is little consensus regarding a definition. Lewin et al. (2009) has suggested that patient-centred care is based on shared control and shared decisions about interventions or the management of health problems with the focus on the whole patient in their psychosocial context.

Although patient-centred care is not a new concept, it is increasingly evidence-based, with studies showing improvements in self-care, quality of life, satisfaction with care, increased engagement and reduced anxiety (Laverty et al., 2009; Whalley Hammell 2009). The physiotherapist, working in collaboration with the interdisciplinary rehabilitation team, discusses and explains treatment options; patients and their care givers (as appropriate) use this information to make decisions about their goals and select treatment solutions. Thus the emphasis should be placed on the patient as the problem solver and the decision maker. The process of goal setting provides a mechanism for patient-centred care by enabling autonomy, and appropriate pacing of information and responsibility (Playford et al., 2009).

Principle 4: Neural plasticity

Although there is always a degree of spontaneous recovery following brain damage, advances in neuroimaging have confirmed that plasticity (enduring changes in structure and function) can occur following damage to the nervous system, and also as a result of experience and therapy. The brain responds to injury by adaptation aimed at restoring function. Thus cortical maps can be modified by a variety of inputs such as sensory inputs, experience, learning and therapy, as well as in response to injury (Nudo, 2007). This ability for neuroplastic change implies that recovery of movement and function should be the main aim of therapy rather than the promotion of independence using the unaffected side, e.g. compensation.

Therapists use different techniques to promote neuroplasticity. There is sound neurophysiological evidence to support the use of afferent information, in particular from the proximal regions, such as the trunk and the hip, as well as the foot, to trigger both postural adjustments and planned sequences of muscle activation during goal-directed movements (Allum et al., 1995; Bloem et al., 2002; Park et al., 1999). The evidence base for applying exercise therapy in functional activities within a meaningful environment and context is also strong (Kwakkel et al., 2004), for example a systematic review by French et al. (2007), has suggested that interventions based on task practice and repetition are more effective than conventional therapy in improving lower limb function after stroke.

Studies have shown that plasticity occurs in association with rehabilitation but further research is required to establish direct links between interventions, neuroplastic change and functional improvement in people following brain damage (see Kleim, 2009, for an overview of animal and human evidence in neurorehabilitation).

Principle 5: A systems model of motor control

Textbooks recommend that a systems model of motor control be adopted, integrating evidence from neurophysiology, biomechanics and motor learning (Carr & Shepherd, 2003). There are many different models of motor control. Shumway-Cook and Woollacott (2007, pp.16–17) recommend a systems model, which considers that solutions to the patient’s motor problems change according to the interaction between the individual, the task and the environment. Although it is important to understand the role of major circuits and pathways of the nervous system (see Kandel et al., 2000, for an overview) and the effects of lesions on these structures and circuits, it is important to understand that there are many subsystems and multiple connections within the nervous system that work in hierarchy and in parallel to generate movement. The actions of a person with damage to the motor control are a consequence of the impairments caused by the damage, the compensatory strategies that enable function to be achieved in the presence of impairments and the effects of the environment the person has been experiencing since the lesion (Bate, 2009).

The key points to remember when designing therapy programmes are that therapists can change the environment, or the task, in such a way that enables the patient to elicit or practice both actions and the tasks required to achieve their goals. See Bate (2009) for an overview of how the motor control system generates movements based on a systems model.

Principle 6: Functional movement re-education

Guidelines of critical features for training actions and functional tasks have been published in expert text books (Carr & Shepherd, 2003; Edwards, 2002). Normative data for everyday activities help therapists to understand motor performance and the impact of impairments on these everyday activities (Carr & Shepherd, 2006); therapists place an emphasis on training control of muscles, and promoting learning of relevant actions and tasks. Therapists aim to optimize movement and function. However, with the majority of neurological conditions, recovery of normal movement and function is not achievable for many patients; this depends to some extent on whether or not the patient has a progressive condition (Edwards, 2002, p. 256).

Physiotherapists use an array of techniques to make movement and function possible, and therapeutic handling is only one of many techniques (see Ch. 12). There is a role for hands-on practice or therapeutic handling, where the therapist manually guides the patient’s movements and activities; as well as a role for hands-off practice where the therapist acts more in the role of a coach to correct movement and functional task performance. It is always preferable to prioritize the practice of functional activities selected in collaboration with the patient. However, if the patient has impairments that make it difficult to practice these tasks directly, therapists may also need to address impairments or practice specific movements, either before or during a modified version of functional task practice (Lennon & Bassile, 2009). For example, a patient may not have any signs of motor activity in the lower limb in order to practice the task of walking. In this case the patient may require either hands on assistance from therapists or support from assistive technologies, e.g. a partial body weight system in order to practice the task of walking. A comprehensive physiotherapy programme may include a wide range of components, such as postural control training, movement re-education (trunk/pelvis/limbs), aerobic training, strengthening exercises, flexibility exercises, and functional task practice, e.g. reach and grasp, bed mobility, transfer and ambulation activities (Lennon & Bassile, 2009). The choice and emphasis of the components will vary depending on the results of each patient’s assessment.

Principle 7: Skill acquisition

There is mounting evidence that task-specific training is required in therapy in order to improve functional recovery (French et al., 2007; Hubbard et al., 2009). Evidence from motor learning and skill acquisition can provide some guiding principles about how to structure practice within therapy sessions (Marley et al., 2000). Motor learning literature differentiates between whole and part practice of a task; yet current evidence does not suggest that whole-task practice is more effective at regaining function than part practice activities (Majsak, 1996; Shumway-Cook & Woollacott, 2007, pp.538-539). Research has highlighted practice and feedback as two crucial issues for therapists. The type of practice used may depend on the task at hand; for example, part practice of fast, discrete tasks or tasks with interdependent parts is less effective than practising the whole task. It has also been suggested that patients need to rely on both intrinsic and extrinsic information to learn new skills (Schmidt et al., 2005).

Motor skill learning can be divided into three phases (Marley et al., 2000):

Certain types of feedback should be used at different points in skill acquisition. For example, manual guidance should mainly be used at the early cognitive stage of motor learning, whereas physical and verbal guidance may actually interfere with motor learning in the later associative and autonomous stages of skill acquisition (Schmidt et al., 2005). Different techniques may work better with different patients; sometimes it will be necessary to practise the components of normal movement that comprise an activity such as pelvic tilting. Sometimes it will work best to break tasks down into the different parts before getting the patient to practise the whole sequence of activity in a functional task. On other occasions it will work best to practise the functional task.

A critical issue for physiotherapy is how much practice is required to improve functional skills (Kwakkel, 2006). Carryover from therapy sessions into everyday activities can be problematic; generalization of treatment effects should be sought by giving the patient activities to practise outside therapy (Lennon, 2003; Marley et al., 2000). The majority of motor learning research is based on normal populations; much more research is required in patients with neurological impairments to determine the most effective ways in which to structure practice and provide feedback.

Principle 8: Self management (self-efficacy)

Whilst it is acknowledged that physiotherapists aim to target both impairments and functional limitations, they also have a role to play in enabling people to return towards meaningful roles in the wider community, with a focus on health and wellness, as well as on ill health and disability (Cott et al., 2007; Dean 2009). Ultimately this means that neurological physiotherapy within rehabilitation involves changing behaviour.

Self-management (the maintenance of health and wellbeing; see Ch. 19) is important as it involves developing skills required to cope with disability and change behaviours necessary to resume desired lifestyles (DoH, 2006). Self-efficacy is a cornerstone of self-management; it is defined as people ’s beliefs about their capabilities to influence key events that affect their lives (Bandura, 2007). People with a strong sense of self-efficacy set themselves challenging goals and maintain strong commitment to them; they continue to sustain their efforts in the face of failure or setbacks (Bandura, 2007). A review specific to physiotherapy by Barron et al. (2007) has shown that self-efficacy can be related to better health, higher achievement, more social integration and higher motivation to act.

Growing evidence provides support for the importance of self-efficacy as a correlate of adherance to therapy (Rhodes & Fiala, 2009). However, evidence is scarce regarding the most effective ways of supporting and enabling individuals with neurological problems to manage ways of living with their chronic disability (Jones, 2006). Physiotherapists need to consider how they can promote self-efficacy and enhance their patients’ self-management skills (see Jones, 2009, for an overview).

Conclusion

Physiotherapists have a key role to play in enabling patients to experience and relearn optimal movement, and function in everyday life within the constraints imposed by neurological disease and presenting impairments. Neurophysiological, motor learning and behavioural principles need to be taken into account in the theoretical framework underlying neurological physiotherapy. This chapter has discussed eight principles derived from Lennon and Bassile (2009) to guide current practice in neurological physiotherapy: the ICF, team work, patient-centred care, neural plasticity, a systems model of motor control, functional movement re-education, skill acquisition and self-management (self-efficacy).

Allum A., Honegger F., Acuna H. Differential control of leg and trunk muscle activity by vestibulo-spinal and proprioceptive signals during human balance corrections. Acta Otolaryngol. (Stockholm). 1995;115:124-129.

Bandura A. Self efficacy in health functioning. In: Ayers S., et al, editors. Cambridge handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. second ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007:191-193.

Barron C.J., Klaber Moffett J.A., Potter M. Patient expectations, of physiotherapy: definitions, concepts and theories. Physiother. Theory Pract.. 2007;23:37-46.

Bate P. Motor Control. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:31-40.

Bernhardt J., Legg L. Chapter 1. Evidence-based practice. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:3-15.

Bloem B.R., Allum J.H., Carpenter M.G., et al. Triggering of balance corrections in a patient with total leg proprioceptive loss. Exp. Brain Res.. 2002;142:91-107.

Bovend’Eerdt T.J.H., Botell R.E., Wade D.T. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin. Rehabil.. 2009;23:352-361.

Carr J.H., Shepherd R.B. Stroke rehabilitation: guidelines for exercise and training to optimise motor skills. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2003.

Carr J.H., Shepherd J.H. Neurological rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2006;28:811-812.

Cott C.A., Wiles R., Devitt R. Continuity, transition and participation: Preparing clients for life in the community post-stroke. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2007;29:1566-1574.

Dean E. Foreword from the Special Issue Editor of ‘Physical Therapy Practice in the 21st Century: A New Evidence-informed Paradigm and Implications. Physiother. Theory Pract.. 2009;25:328-329.

Department of Health (DoH). Supporting people with long term conditions to self-care: a guide to developing local strategies and good practice. 2006. March

Edwards S. Neurological Physiotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

French B., Thomas L.H., Leathley M.J., Sutton C.J., McAdam J., Forster A., et al. Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke (Review). The Cochrane Library. (4):2007.

Hubbard I.J., Parsons M.W., Neilson C., Carey L.M. Task-specific training: evidence for and translation to clinical practice. Occup. Ther. Int.. 2009;16:175-189.

Jones F. Strategies to enhance chronic disease self-management: how can we apply this to stroke? Disabil. Rehabil.. 2006;28:841-847.

Jones F. Continuity of care. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:203-210.

Kandel E.R., Schwartz J.A., Jessell T.M. Principles of Neural Science, fourth ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2000.

Keus S., Bloem B., Hendriks E., et al. Evidence-based analysis of physical therapy in Parkinson’s Disease with recommendations for practice and research. Mov. Disord.. 2006;22:451-460.

Kilbride C., Cassidy E. The acute patient before and during stabilisation; stroke, traumatic brain injury, Guillain Barre Syndrome. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:127-135.

Kleim J.A. Neural plasticity in motor learning and motor recovery. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:41-50.

Kollen B.J., Lennon S., Lyons B., Wheatley-Smith L., Scheper M., Buurke J., et al. The effectiveness of the Bobath Concept in stroke rehabilitation: what is the evidence. Stroke. 2009;40:e89. –1e87

Kwakkel G. Impact of intensity of practice after stroke: issues for consideration. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2006;28:823-830.

Kwakkel G., Kollen B., Lindeman E. Understanding the pattern of functional recovery after stroke. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci.. 2004;22:281-299.

Laverty A.M., Jones Z., Rodgers H. Ensuring patient and carer-centred care. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:17-24.

Lennon S. Physiotherapy practice in stroke rehabilitation: a survey. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2003;25:455-461.

Lennon S., Bassile C. Guiding Principles for neurological physiotherapy. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Ltd; 2009:97-111.

Levack W.M.M., Dean S.G., Siegert R.G., McPherson K.M. Purposes and mechanisms of goal planning in rehabilitation: the need for a critical distinction. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2006;28:741-749.

Lewin S., Skea Z., Entwistle V.A., Zwarenstein M., Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations (Review). The Cochrane Library. (3):2009.

Long A.F., Kneafsey R., Ryan J. Rehabilitation practice: challenges to effective team working. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.. 2003;40:663-673.

Majsak M.J. Application of motor learning principles to the stroke population. Top. Stroke Rehabil.. 1996;3:27-59.

Marley T.L., Ezekiel H.J., Lehto N.K., Wishart L.R., Lee T.D. Application of motor learning principles: the physiotherapy client as a problem solver. II. Scheduling practice. Physiother. Canada. 2000;52:315-320.

MS Society. Translating the NICE MS Guideline into practice: a physiotherapy guidance document, London, second ed. London: MS Society, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy and Association of Physiotherapists in Neurology, 2008.

NCGS. National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Available online at: http:/www.rcplondon.ac.uk/pubs/books/stroke

Nudo R. Post-infarct cortical plasticity and behavioural recovery. Stroke. 2007;38:840-845.

Park S., Toole T., Lee S. Functional roles of the proprioceptive system in the control of goal-directed movement. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1999;88:631-647.

Playford E.D., Siegert R., Levack W., freeman J. Areas of consensus and controversy about goal setting in rehabilitation: a conference report. Clin. Rehabil.. 2009;23:334-344.

Pollock A., Baer G., Pomeroy V., Langhorne P. Physiotherapy treatment approaches for the recovery of postural control and lower limb function following stroke. The Cochrane Library. (1):2007.

Rhodes R.E., Fiala B. Building motivation and sustainability into the prescription and recommendations for physical activity and exercise therapy: the evidence. Physiother. Theory Pract.. 2009;25:424-441.

Ryerson S. Neurological assessment: the basis of clinical decision making. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:113-126.

Schmidt R.A., Lee T. Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioural Emphasis, fourth ed. Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2005.

Shepard K. Theory: criteria, importance and impact. In: Proceedings of the 2nd STEP Conference on Contemporary Management of Motor Control Problems. Virginia: Foundation for Physical Therapy; 1991:5-10.

Shumway Cook A., Woollacott M.H. Motor Control translating research into clinical practice. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

Sivaraman Nair K.P., Wade D.T. Satisfaction of members of interdisciplinary rehabilitation teams with goal planning meetings. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 2003;84:1710-1713.

Stroke Unit Trialists Collaboration (SUTC). Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke(review). The Cochrane Library. (3):2006.

Van Peppen R.P.S., Kwakkel G., Wood-Dauphinee S., et al. The impact of physical therapy on functional outcomes after stroke: what’s the evidence? Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:833-862.

Van Peppen R.P.S., Hendriks H.J., van Meeteren N.L., Helders P.J., Kwakkel G. The development of a clinical practice stroke guideline for physiotherapists in The Netherlands: a systematic review of available evidence. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2007;29:767-783.

Wade D.T. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin. Rehabil.. 2009;23:291-295.

Whalley Hammell K. The wider context of neurorehabilitation. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Science; 2009:25-30.

World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. Available online at: http:/www.who.int/classification/icf