16 The Thalamus and Internal Capsule: Getting to and from the Cerebral Cortex

The diencephalon is a relatively small, centrally located part of the cerebrum that, like the spinal cord and brainstem, is functionally important way out of proportion to its size. It is subdivided into four general regions, each with the term “thalamus” as all or part of its name.

The Diencephalon Includes the Epithalamus, Subthalamus, Hypothalamus, and Thalamus

The major components of the diencephalon, the thalamus and hypothalamus, are active in practically everything we do. The thalamus is the gateway to the cerebral cortex and the principal subject of this chapter. The hypothalamus regulates autonomic functions and drive-related behavior and is discussed further in Chapter 23.

The epithalamus and subthalamus are located where their names imply—above and below the thalamus, respectively. The major constituent of the epithalamus is the pineal gland, an endocrine gland near the posterior commissure and the midbrain-diencephalon junction. It secretes melatonin, a hormone involved in the regulation of circadian rhythms and seasonal cycles. The major constituent of the subthalamus is the subthalamic nucleus, an important part of the basal ganglia (Chapter 19).

The Thalamus Is the Gateway to the Cerebral Cortex

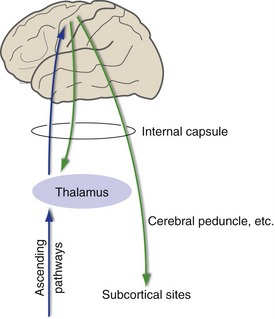

Some collections of chemically coded fibers, such as serotonergic fibers from the raphe nuclei and noradrenergic fibers from the locus ceruleus, reach the cerebral cortex directly. However, the vast majority of the afferents to the cerebral cortex arise either in the cortex itself or in the thalamus. Thalamocortical afferents include fibers representing all the specific sensory, motor, and limbic pathways. In contrast, efferents from the cerebral cortex to sites like the spinal cord, brainstem, and basal ganglia reach their targets directly. (Although there are also many cortical projections back to the thalamus, these do not form a link in any descending pathway.) This large collection of thalamocortical afferents and cortical efferents travels through the internal capsule (Fig. 16-1).

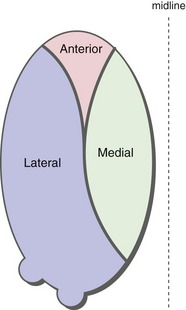

The Thalamus Has Anterior, Medial, and Lateral Divisions, Defined by the Internal Medullary Lamina

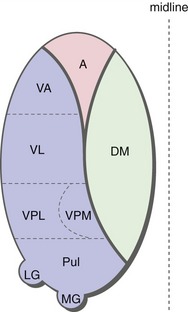

A thin sheet of myelinated fibers, the internal medullary lamina, subdivides the thalamus into nuclear groups. The internal medullary lamina bifurcates anteriorly and so defines anterior, medial, and lateral nuclear groups (Fig. 16-2).

The anterior and medial subdivisions have only one major nucleus each (the anterior and dorsomedial nuclei, respectively). The lateral division, in contrast, contains an array of four major nuclei or nuclear groups. From anterior to posterior these are the ventral anterior nucleus (VA), the ventral lateral nucleus (VL), the ventral posterolateral and ventral posteromedial nuclei (VPL and VPM), and the pulvinar (Fig. 16-3). In addition, the lateral and medial geniculate nuclei (LGN and MGN) form two bumps posteriorly and inferiorly on the main bulk of the thalamus.

Patterns of Input and Output Connections Define Functional Categories of Thalamic Nuclei

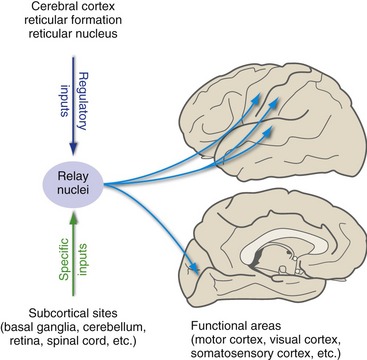

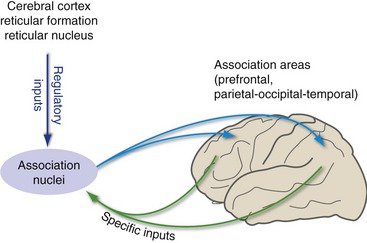

Thalamic nuclei that receive most of their specific inputs from subcortical structures are relay nuclei (Fig. 16-4); the medial geniculate nucleus, for example, receives most of its specific inputs from the inferior colliculus and relays this information to auditory cortex. (The intralaminar and midline nuclei also receive specific inputs from subcortical sites, in this case parts of the basal ganglia and limbic system, but send more outputs to the basal ganglia and limbic system than to cerebral cortex; their functional role is not well understood.) Thalamic nuclei that receive most of their specific inputs from the cerebral cortex are association nuclei, which are important for distributing information between different cortical areas (Fig. 16-5).

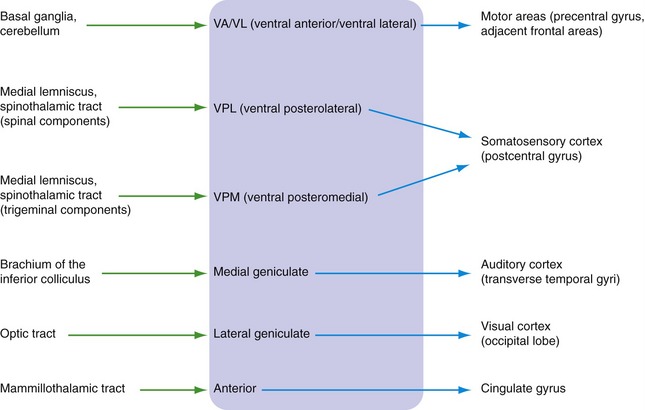

There Are Relay Nuclei for Sensory, Motor, and Limbic Systems

Thalamic relay nuclei are part of specific functional systems, receiving particular bundles of afferents and projecting heavily to particular cortical areas with more or less well-defined functions. The major examples of specific relay nuclei, with their inputs and outputs, are indicated in Fig. 16-6.

The Dorsomedial Nucleus and Pulvinar Are the Principal Association Nuclei

Most of the cortical areas not accounted for in the projections of the thalamic relay nuclei form two large expanses of association cortex (see Chapter 22). The first, prefrontal association cortex, is located anterior to the motor areas of the frontal lobe. The second is the parietal-occipital-temporal association cortex. Each of these fields of association cortex receives major inputs from its own thalamic association nucleus, prefrontal areas from the dorsomedial nucleus and more posterior areas from the pulvinar.

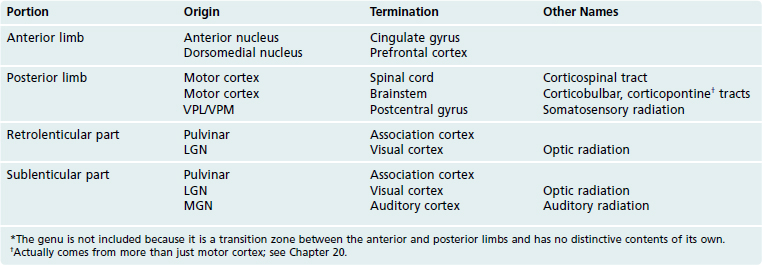

Interconnections between the Cerebral Cortex and Subcortical Structures Travel through the Internal Capsule

Most cortical afferents and efferents travel through the internal capsule, a bundle of fibers compacted between the lenticular nucleus (lateral to it) and the thalamus and head of the caudate (medial to it). (Its three-dimensional shape can be seen in THB6 Figure 16-23, p. 410.)

The major contents of the various parts of the internal capsule can be inferred, for the most part, from their positions relative to various thalamic nuclei and cortical areas (Table 16-1; see THB6 Figures 16-24 and 16-25, pp. 411 and 412).