The temporomandibular joint

Introduction

From the investigative point of view the knowledge required by clinicians includes:

Normal anatomy

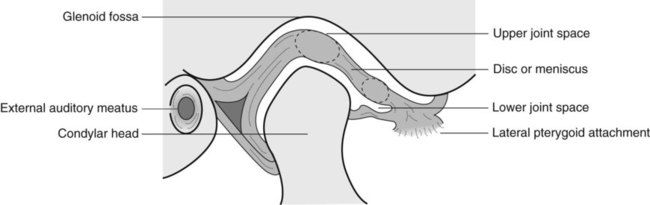

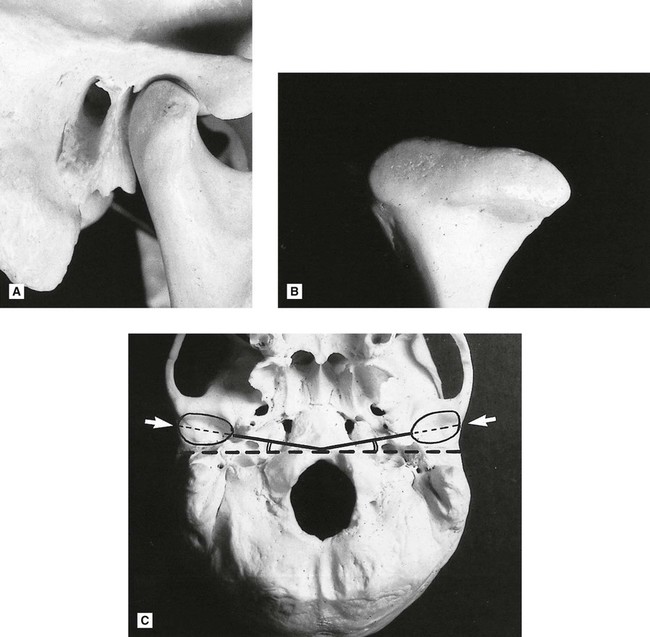

The basic components of the TMJ include:

• The mandibular component, i.e. the head of the condyle

• The temporal component, i.e. the glenoid fossa and articular eminence

• The capsule surrounding the joint (see Figs 30.1 and 30.2).

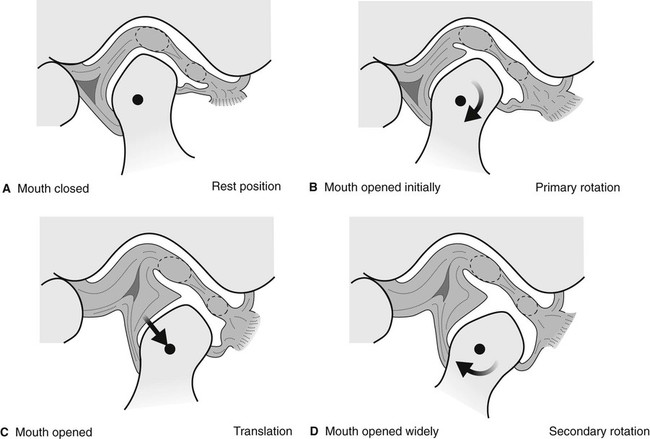

In addition to this knowledge of the static anatomy, clinicians need to be aware of the types and range of joint movements which result in the condyles moving downwards and forwards when patients open their mouths. These include:

Investigations

Modern imaging of the TMJ is dependent on the facilities available but could include:

• Conventional panoramic radiography

• Specific field limitation TMJ panoramic programmes

Previously described transorbital and transcranial views are now seldom used and are only of historical interest.

Panoramic radiography

Main indications

The main clinical indications include:

• TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome if bone anomalies are suspected clinically

• To investigate disease within the joint

• To investigate pathological conditions affecting the condylar heads

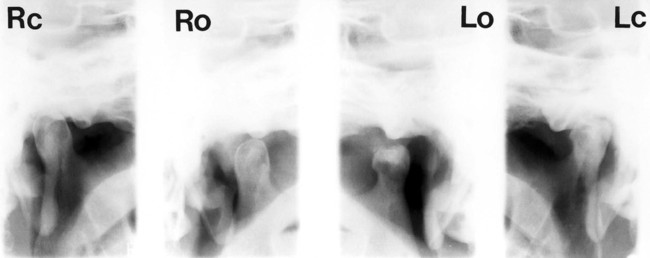

Panoramic TMJ programmes

Main indications

Technique summary

The technique can be summarized as follows:

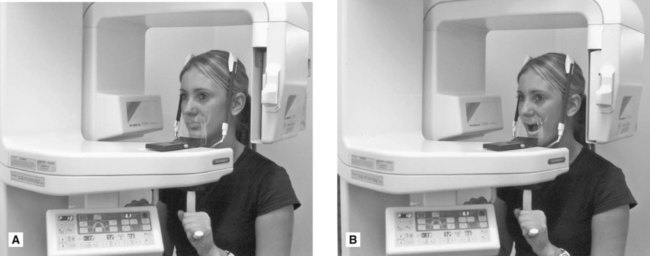

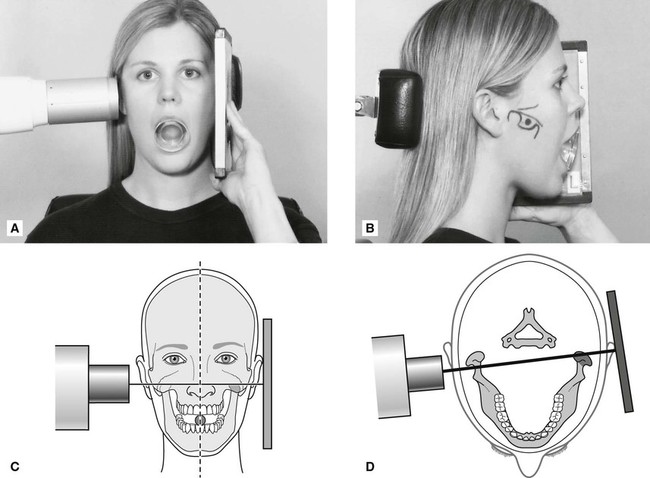

• The patient is positioned with their Frankfurt plane angled 5° downwards within a panoramic unit with their mouth closed but using a special nose/chin support as shown in Fig. 30.5A instead of the bite-peg

• The head is accurately positioned using the light beam markers and immobilized using the temple supports

• The distance from the external auditory meatus to the canine light is measured and the anteroposterior position of the chin support adjusted manually to ensure that the condyles appear in the middle of the image

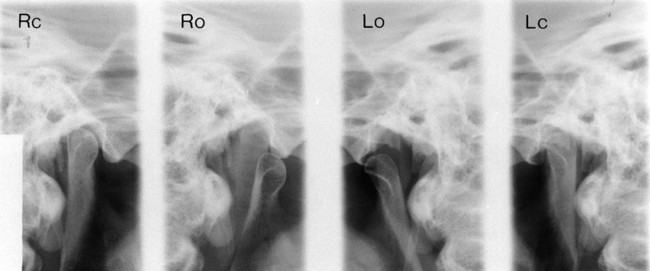

• During the exposure, first the left and then the right condyle is imaged in the closed position

• The equipment automatically returns to the start position

• The patient is instructed to open the mouth, as shown in Fig. 30.5B

• The left and right condyles are then exposed in the open position and the resultant image is shown in Fig. 30.6.

Transpharyngeal radiography

Main indications

The main clinical indications include:

• TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome

• To investigate the presence of joint disease, particularly osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis

• To investigate pathological conditions affecting the condylar head, including cysts or tumours

Technique and positioning

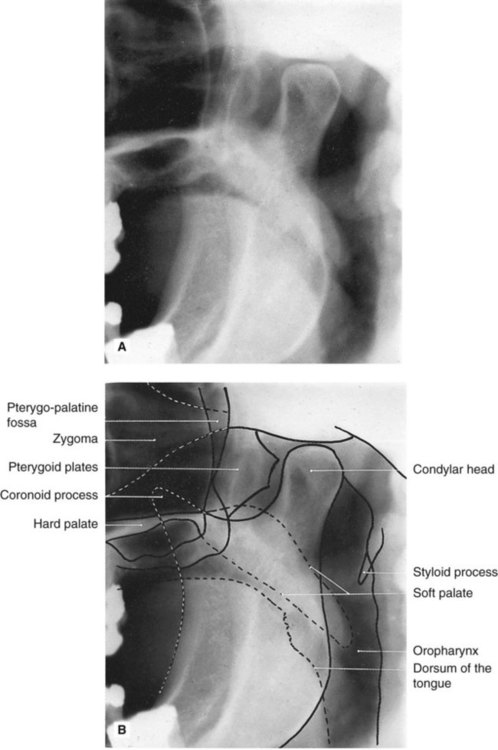

1. The patient holds the cassette against the side of the face over the TMJ of interest. The film and the mid-sagittal plane of the head are parallel. The patient’s mouth is open and a bite-block is inserted for stability.

2. The X-ray tubehead is positioned in front of the opposite condyle and beneath the zygomatic arch. It is aimed through the sigmoid notch, slightly posteriorly, across the pharynx at the condyle under investigation, as shown in Fig. 30.7. Usually this view is taken of both condyles to allow comparison.

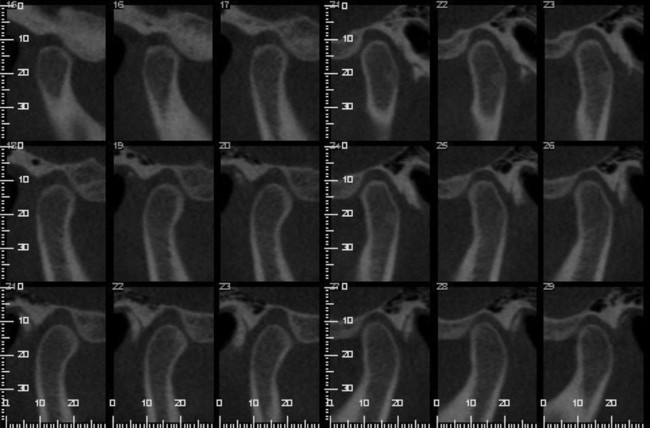

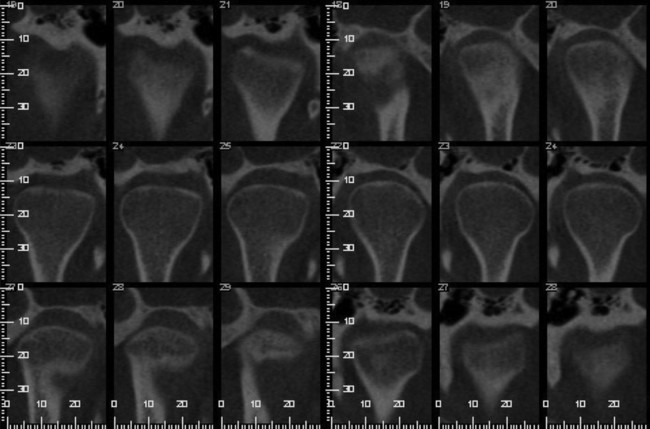

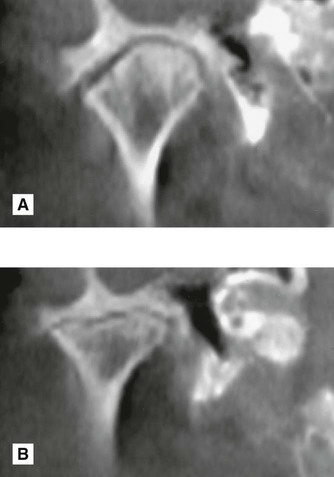

Cone beam CT

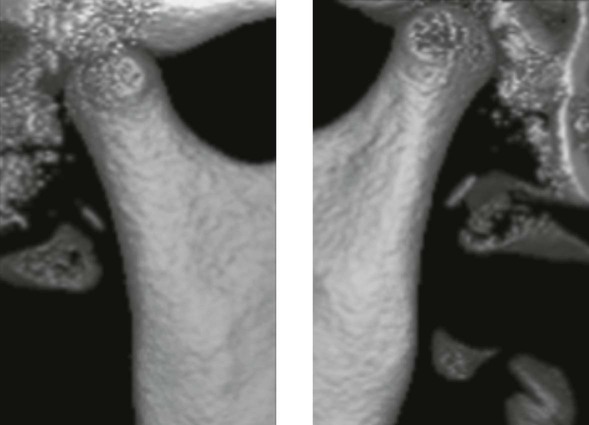

Cone beam CT (CBCT) described in Chapter 16 is increasingly being used as an alternative to CT to image the bony elements of the TMJ as shown in Figs 30.9 and 30.10. Sectional or slice images of all aspects of the joints are produced, but in addition, using appropriate software, 3-D images can be created, as shown in Fig. 30.11.

Main indications

The main clinical indications include:

• Full assessment of the whole of the joint to determine the presence and site of any bone disease or abnormality

• To investigate the condyle and articular fossa when the patient is unable to open the mouth

• Assessment of fractures of the condylar head and articular fossa and intracapsular fractures.

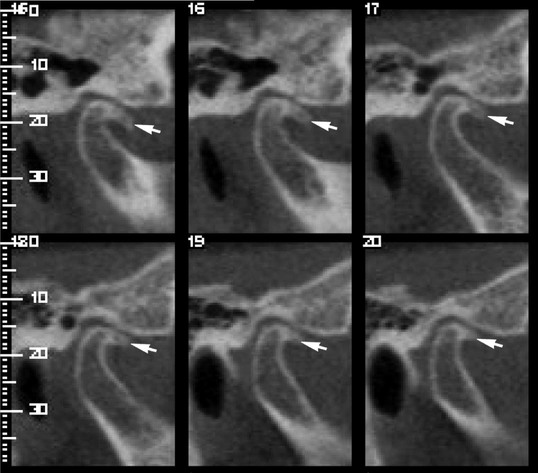

Magnetic resonance (MR)

Magnetic resonance imaging described in Chapter 18 is now established as one of the more useful investigations of the bony and soft tissue elements of the TMJ. It is particularly useful for determining the position and form of the disc when the mouth is both open and closed (see Fig. 30.12). As mentioned in Chapter 18, cineloop or pseudodynamic echo sequences are generally used for TMJ imaging:

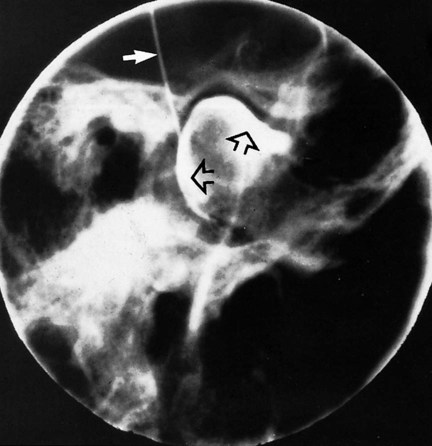

Arthrography

Main indications

• Longstanding TMJ pain dysfunction unresponsive to simple treatments

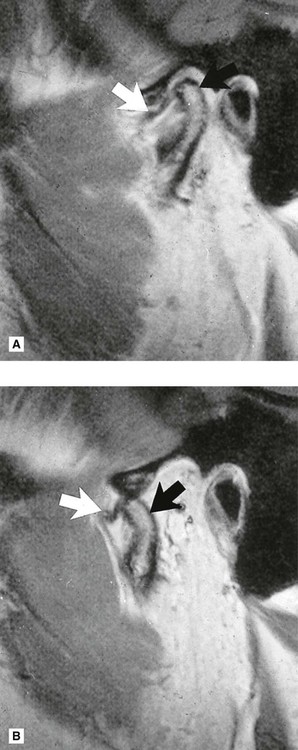

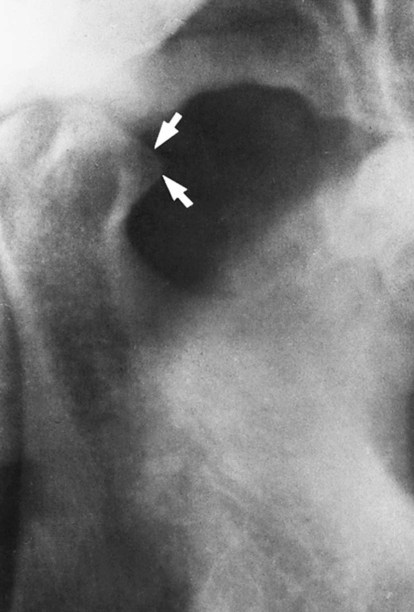

Technique (Fig. 30.13)

This can be summarized as follows:

1. Non-ionic aqueous contrast medium (e.g. iopamidol-Niopam® 370) is injected carefully into the lower joint space, using fluoroscopy to aid the accurate positioning of the needle.

2. The primary record is obtained ideally using video-recorded fluorography or cinefluorography which allows imaging of the joint components as they move. Only the lateral aspects of the joints are seen.

3. Thin-section tomography of the joint can also be performed if required, to provide information on the medial and lateral aspects of the joint. Typically, five or six slices, 2–3 mm apart, are used with the patient’s mouth open and closed.

4. If further information is required, the contrast medium can be introduced into the upper joint space and the investigation repeated.

Diagnostic information

The information provided includes:

• Dynamic information on the position of the joint components and disc as they move in relation to one another

• Static images of the joint components with the mouth closed and with the mouth open. Any anterior or anteromedial displacement of the disc can be observed

• The integrity of the disc, i.e. the presence of any perforations.

Note: Outlining the lower joint space usually provides the more useful information on the disc.

Main pathological conditions affecting the TMJ

The main pathological conditions that can affect the TMJ include:

• TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome (myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome)

• Osteoarthritis (osteoarthrosis)

TMJ (myofascial) pain dysfunction syndrome

Main radiographic features

• Normal condylar head shape and articular surface

• Possible increase or reduction in the overall size of the joint space – an increase in the size of the joint space is only indicative of inflammation

• Possible displacement of the condylar head anteriorly or posteriorly in the glenoid fossa when the mouth is closed and the teeth are in occlusion

Note In their 2011 publication iRefer: Making the Best Use of Clinical Radiology the Royal College of Radiologists in the UK state that in relation to TMJ dysfunction, radiographs ‘do not add information as the majority of temporomandibular joint problems are due to soft tissue dysfunction rather than bony changes (which appear late and are often absent in the acute phase)’.

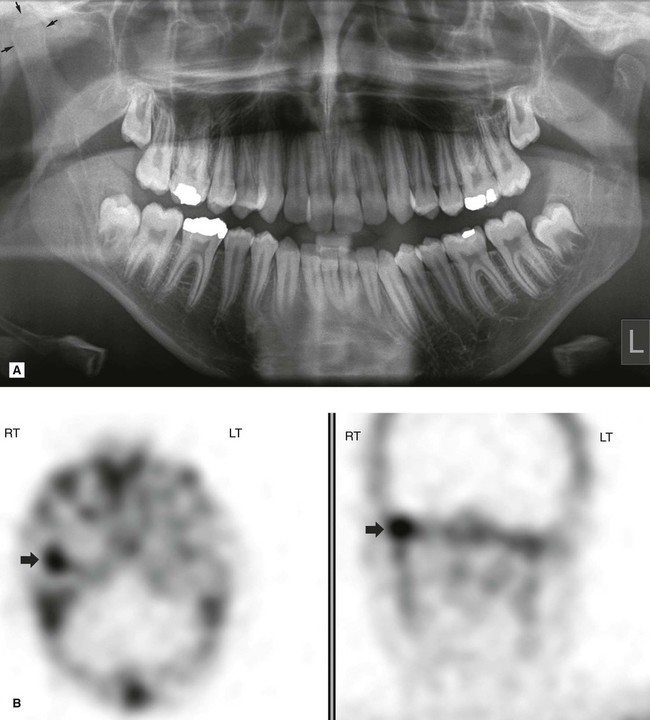

Osteoarthritis

Main radiographic features (see Figs 30.14–30.17)

• Osteophyte (bony spur) formation on the anterior aspect of the articular surface of the condylar head. The radiological appearance of small osteophyte formation is often referred to as lipping; extensive osteophyte formation is referred to as beaking

• Flattening of the head of the condyle on the anterosuperior margin

• Subchondral sclerosis of the condylar head which becomes dense and more radiopaque – a process sometimes referred to as eburnation

• A normal outline to the glenoid fossa though it may also become sclerotic

Rheumatoid arthritis

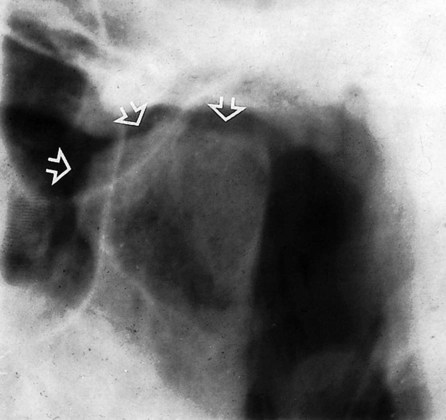

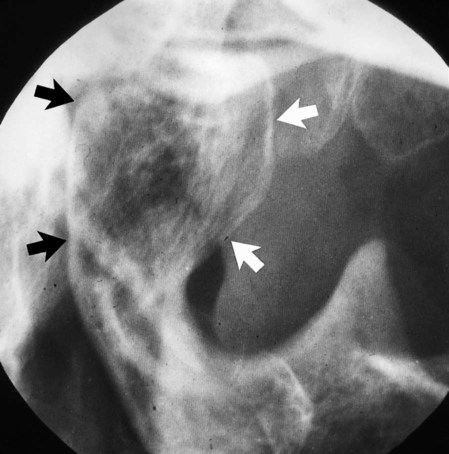

Main radiographic features (see Figs 30.18–30.20)

• Flattening of the head of the condyle

• Erosion and destruction of the articular surface of the head of the condyle which may be extensive causing the outline to become irregular

• Occasional osteophyte formation on the condylar head

• Hollowing of the glenoid fossa

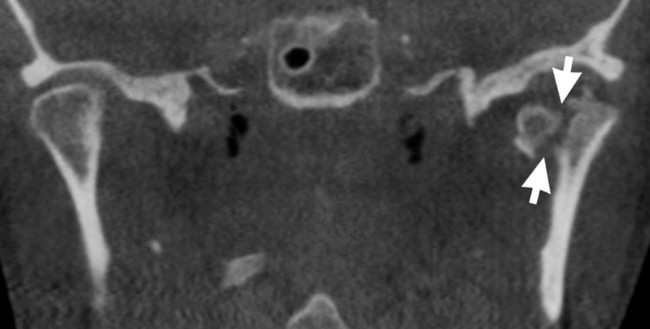

Ankylosis

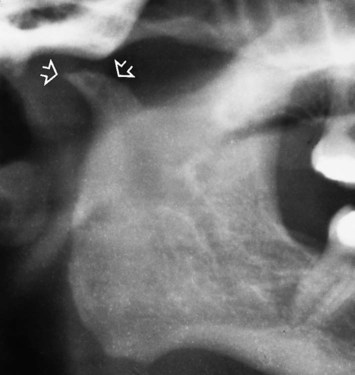

True ankylosis, i.e. fusion of the bony elements of the joint (see Fig. 30.21), is uncommon but is usually the result of:

Tomography, cone beam CT or CT are the investigations of choice because of the obvious problems of opening the mouth.

Main radiographic features

• Little or no evidence of a joint space

• Bony fusion between the head of the condyle and the glenoid fossa with total loss of the normal anatomical outlines

• Associated evidence of condylar neck hypoplasia and mandibular underdevelopment on the affected side producing asymmetry, if the ankylosis precedes completion of mandibular growth. A prominent antegonial notch on the affected side is often evident.

Tumours

Benign or malignant tumours develop occasionally in the head of the condyle. The radiographic features depend on the type and nature of the tumour involved, but there is usually an alteration in the shape of the condylar head. Typical examples include osteoma, chondroma (see Fig. 30.22) and chondrosarcoma.

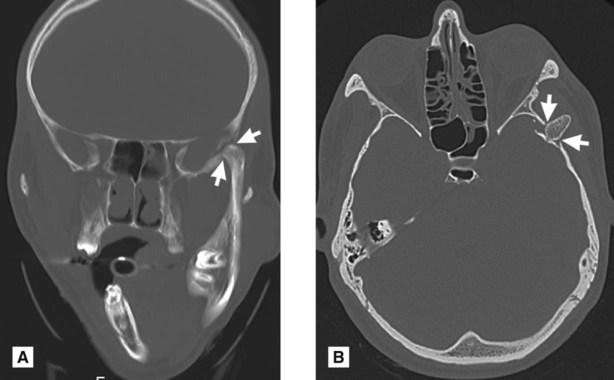

Fractures and trauma

Fractures of the condylar necks are common after a blow to the chin (see Ch. 29). Very occasionally with this type of injury the condylar neck does not fracture but the head of the condyle either fractures, a so-called intra-capsular fracture (see Fig. 30.23) or is forced upwards, through the glenoid fossa into the middle cranial fossa (see (Fig. 30.24). Tomography, cone beam CT or CT will demonstrate the extent of any injury. Trauma can also result in unilateral or bilateral dislocation (see Fig. 30.25).