The Tear Film

Anatomy, Structure and Function

Tear Film Anatomy and Physiology

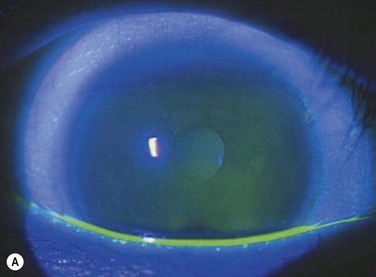

One of the primary functions of the tear film includes providing ocular surface comfort through continuous lubrication. Tears are continually replenished from the inferior tear meniscus by blinking.1 This counters the forces of gravity and evaporation on the volume of the precorneal tear film and protects corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells from the shear forces exerted by the eyelids during blinking. Tear production is approximately 1.2 microliters per minute, with a total volume of 6 microliters and a turnover rate of 16% per minute.2 Tear film thickness, as measured by interferometry, is 6.0 µm ± 2.4 µm in normal subjects and is significantly thinner in dry eye patients with measured values as low as 2.0 µm ± 1.5 µm (Fig. 3.1).3

The ocular surface is the most environmentally exposed mucosal surface, and the tear film serves to protect against irritants, allergens, environmental extremes of dryness and temperature, potential pathogens and pollutants. Reflex tearing can help flush pathogens and irritants from the ocular surface. Antimicrobial components of the tear film include peroxidase, lactoferrin, lysozyme, and immunoglobulin A, among others. The superficial lipid component of the tear film helps prevent evaporation.4

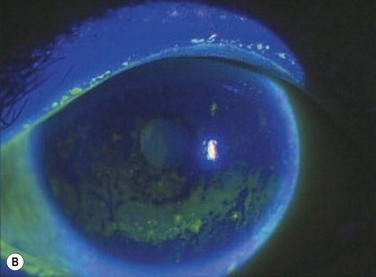

Because the cornea is an avascular structure, the epithelium relies on the tear film to supply glucose, electrolytes, and growth factors, as well as the elimination of waste and free radicals. The tear film is a dilute protein solution that shares similar components to serum, although in different concentrations. Glucose concentration is much lower than in plasma (25 mg/L compared to 85 mg/L), and chlorine and potassium are higher. Other electrolyte components include calcium, magnesium, bicarbonate, nitrate, phosphate, and sulfate. Antioxidants, such as Vitamin C, tyrosine, and glutathione scavenge free radicals to help minimize cellular oxidative damage. The tear film also provides a large number of growth factors, neuropeptides, and protease inhibitors, important in maintaining corneal health and stimulating wound healing (Fig. 3.2, Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

Growth factors, neuropeptides, and protease inhibitors in the tear film.

| Transforming growth factor (TGF-α,β1,β2) | Mitogenic, inhibits corneal epithelial cell proliferation, pro-fibrotic |

| Tear hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), keratocyte growth factor | Stimulates corneal epithelial cells, promotes wound healing |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGFβ, FGF2), Epidermal growth factor | Mitogenic |

| Substance P | Neuropeptide; stimulates epithelial growth, wound healing |

| Plasminogen, plasmic, plasminogen activator | Proteases, matrix degradation/wound healing |

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2,3,8,9) | Matrix degradation/wound healing |

| Tryptase, α1-antichymotrypsin, α1-protease inhibitor, α2-macroglobulin | Protease inhibitors |

(Adapted with permission from Beuerman R. Tear Film. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editor. Cornea. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. p. 45–52.)

The tear film provides a smooth refracting surface over the microvilli of the corneal epithelium. The air–fluid interface of the tear film is a powerful lens that supplies two-thirds of the refracting power of the eye. It is also evident that desiccation and tear film instability can lead to visual degradation and symptoms of fluctuating vision, loss of contrast, and/or discomfort.5

Structure and Stability

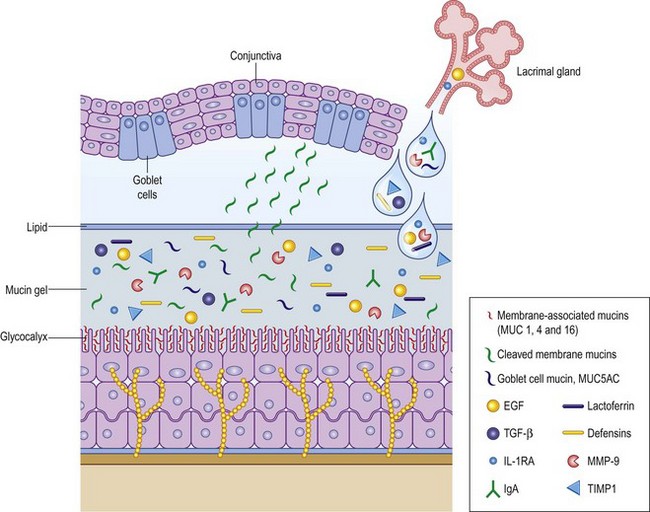

The ocular surface requires a dynamic yet stable tear film to meet the environmental, immunologic, and optical challenges presented to it. For decades, a discrete three-layer model was accepted, consisting of an anterior lipid layer to provide protection from evaporation; an aqueous component that provided the largest part of tear film volume; and a mucin layer that provided protection and lubrication of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium. A more recently proposed model consists of a mucin/aqueous glycocalyx gel that comprises most of the tear film volume with an external protective lipid layer to resist evaporative forces (Fig. 3.3).3

Lipids

A heterogeneous mixture of lipids is secreted by the meibomian glands, located posterior to the lash line in the upper and lower eyelids. The low surface tension of the lipid layer enables uniform spread of the tear film and provides an optically smooth refracting surface. The posterior aqueous interface of the lipid layer consists primarily of polar lipids including ceramides, cerebrosides and phospholipids. Nonpolar lipids form the lipid–air interface, including cholesterol esters, triglycerides, and free fatty acids.6

Aqueous Component

The aqueous portion of the mucin/aqueous gel contains proteins, electrolytes, oxygen, and glucose (Table 3.1). Electrolyte concentration of this layer is similar to that of serum, resulting in an average osmolarity of 300 mOsm/L. Tear osmolarity correlates highly with dry eye syndrome and will likely be increasingly utilized as a metric for diagnosis and classification of the disorder.7 Normal osmolarity is essential to maintain cellular volume, enzymatic activity, and cellular homeostasis. Matrix metalloproteinases, particularly MMP-9, serve an important role in wound healing and inflammation, and are substantially up-regulated in dry eye syndrome. Aqueous volume is constantly replenished by the main and accessory lacrimal glands. Most non-reflex tear production is from the glands of Krause and Wolfring, accessory lacrimal glands located in the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper eye lid and the superior conjunctival fornix. The lacrimal glands can provide a substantial volume of aqueous tears when the ocular surface is presented with a noxious stimulus, such as a foreign body, chemical irritant, or epithelial injury. It is unclear what role the lacrimal gland plays in non-reflex tearing, but it appears to be important, as evidenced by the frequency of dry eye syndrome in patients with infiltrative lacrimal gland disease or after surgical removal.

Tear production is neurally driven by a reflex loop that links the ocular surface, central nervous system stimulation, and the glands of the ocular surface. The lacrimal functional unit (LFU) comprises the cornea, conjunctiva, and meibomian glands of the ocular surface, the main and accessory lacrimal glands, and the neural pathways that connect them.8 Afferent sensory nerves of the cornea and conjunctiva synapse with higher-order sensory neurons, autonomic, and motor efferent nerves in the brainstem. When that stimulus is interrupted by local or general anesthesia, corneal nerve transection after LASIK, or neurotrophic infection, tear production decreases and dryness ensues. Lacrimal and accessory glands, meibomian glands, and conjunctival goblet cells are innervated by autonomic nerve fibers. Motor fibers from the facial nerve innervate the orbicularis oculi muscle and stimulate the blink reflex which distributes tears evenly over the ocular surface.4

Mucins

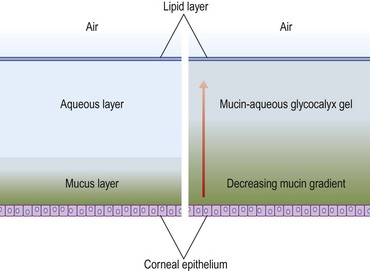

The mucin component of the glycocalyx gel consists of an organized and heterogeneous group of glycoproteins that promote a firm attachment of the matrix to the corneal epithelium, provide viscosity, and a low surface tension that aids uniform re-wetting of the hydrophobic ocular surface. Corneal and conjunctival epithelium express transmembrane mucins (MUC 1,2,4), which anchor the aqueous/mucin glycocalyx to the cell surface. The lacrimal gland and conjunctival goblet cells secrete mucin into the tear film and these glycoproteins likely play a role in preventing adherence and interaction of microbes, debris, and inflammatory cells with the epithelium.9 Mucins also provide viscosity that protects the fragile corneal epithelium from the repetitive forces of blinking, and they lower surface tension, which produces the smooth, uniform, optically advantageous properties of the tear film.

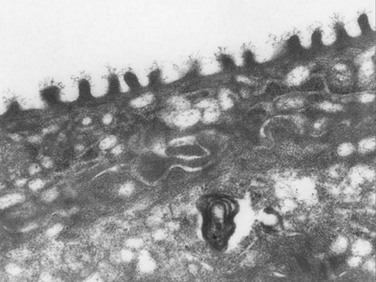

The corneal surface is squamous epithelium approximately five cell layers thick. Microvilli on the apical surface have filaments that interact with mucins that expand into the tear film, supporting it and forming a glycocalyx gel (Fig. 3.4). Increased surface area of the microvilli provides a strong anchor that stabilizes the tear film and protects the cornea. The mucin matrix decreases surface tension and facilitates uniform re-wetting of the epithelium and close interaction between the hydrophilic aqueous component and the hydrophobic epithelial cell membranes. Cellular tight junctions on the corneal epithelium form a barrier that provides protection from inflammatory and microbial insults. Corneal epithelial cells live approximately 7 to 10 days and undergo an organized apoptosis and desquamation that is highly regulated by matrix metalloproteinases and other signaling molecules. Complete turnover occurs weekly as deeper basal epithelium moves toward the apex of the cornea.10

Tear Dysfunction

Tear dysfunction is a common and potentially debilitating condition that results in a broad spectrum of symptoms with varying degrees of severity. The most common result of tear dysfunction is epithelial disease, which can cause dryness, foreign body sensation, fluctuation in visual quality, decreased contrast, and photophobia. Dysfunction of any component of the lacrimal functional unit can cause tear dysfunction and a resulting epitheliopathy, including conjunctivochalasis, eyelid malposition, and lacrimal or meibomian gland disease. There is general consensus of two main subtypes of dry eye syndrome; evaporative and aqueous dry eye. These are a result of a dysfunction of the meibomian and lacrimal glands. The tests most commonly utilized to assess dry eye severity are the Schirmer test, tear film breakup time (TBUT), fluorescein, rose bengal, lissamine green staining of the ocular surface, and symptom scoring with patient questionnaires, such as the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI).11

Osmolarity

One of the principal indicators of tear dysfunction is elevated tear film osmolarity, predominantly due to elevated sodium ion concentration. Elevated osmolarity is considered the central mechanism of ocular surface damage and may be the single best marker for dry eye disease, as reported in the Dry Eye Workshop Report.12 In rabbit studies, tear osmolarity is directly correlated with tear evaporation and flow rate. Increased osmolarity also correlates with decreased goblet cell density, granulocyte survival, and causes significant morphological changes in tissue culture. In a meta-analysis, Tomlinson et al. report an average tear osmolarity of 302 ± 9.7 in normal subjects (815) and 326.9 ± 22.1 in subjects with keratoconjunctivitis sicca (621). A cut-off value of 316 mOsmol/L appears to provide acceptable sensitivity (69%) and specificity (92%) for the diagnosis of keratoconjunctivitis sicca.13

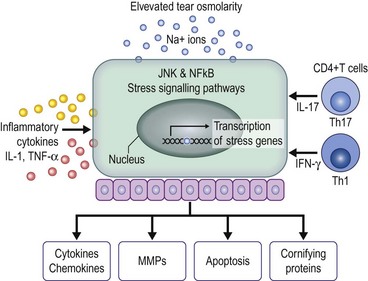

Hyperosmolarity causes significant corneal epithelial stress that may result in increased levels of inflammatory mediators including proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 3.5). These mediators initiate stress-signaling pathways that result in expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear-factor B (NFB) in corneal epithelial cells and immune activation and adhesion molecules (HLA-DR and ICAM-1) in conjunctival epithelium. These molecules attract conjunctival inflammatory cells and are found in increased frequency in the conjunctiva of dry eye patients, as measured by flow cytometry.14

Dry eye patients exhibit increased activity and concentration of matrix metalloproteinases in the tear film, particularly MMP-9. These enzymes play an important role in regulation of epithelial cell desquamation and cleave a variety of substrates in the corneal epithelial basement membrane and tight junction proteins (occludins), that help maintain epithelial barrier function. The sequelae of these activities include corneal surface irregularities, punctate epithelial erosions due to increased epithelial desquamation, apoptosis, and increased fluorescein permeability.14

The tear film must respond to a constant barrage of mechanical and chemical irritants, pathogenic invaders, environmental extremes, and be able to mount a healing response quickly. The defensins are a group of naturally occurring peptides present in the tear film that have wound healing and innate antimicrobial properties. Their antimicrobial activity is broad and encompasses viruses (HIV, HSV), fungi, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The peptides form a rigid three-dimensional structure that forms voltage-sensitive channels in the plasma membrane of the target organism. Defensins also accelerate wound healing due to their mitogenic effect on fibroblasts and epithelial cells. In addition, these may facilitate a rapid immune response through stimulating monocyte chemotaxis.15

References

1. Palakuru, JR, Wang, J, Aquavella, JV. Effect of blinking on tear dynamics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3032–3037.

2. Mishima, S, Gasset, A, Klyce, SD, et al. Determination of tear volume and tear flow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1966;5:264–269.

3. Hosaka, E, Kawamorita, T, Ogasawara, Y, et al. Interferometry in the evaluation of precorneal tear film thickness in dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:18–23.

4. Stern, ME, Beuerman, RW, Pflugfelder, SC. The normal tear film and ocular surface. In: Pflugfelder SC, Stern ME, Beuerman RW, eds. Dry eye and the ocular surface. New York: Marcel-Dekkar; 2004:11–40.

5. Rolando, M, Zierhut, M. The ocular surface and tear film and their dysfunction in dry eye disease. Surv Ophthalmology. 2001;45(2):S203–S210.

6. McCulley, JP, Shine, W. A compositional based model for the tear film lipid layer. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;95:79–88.

7. Lemp, MA, Bron, AJ, Baudouin, C, et al. Tear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:792–798. [e1. Epub 2011 Feb 18. PubMed PMID: 21310379].

8. Stern, ME, Beuerman, RW, Fox, RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: the interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea. 1998;17:584–589.

9. Gipson, IK, Inatomi, T. Cellular origin of mucins of the ocular surface tear film. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:221–227.

10. DelMonte, DW, Kim, T. Anatomy and physiology of the cornea. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:588–598. [Review].

11. Korb, DR. Survey of preferred tests for diagnosis of the tear film and dry eye. Cornea. 2000;19:483–486.

12. International Dry Eye Workshop. The definition and classification of dry eye disease. In: 2007 Report of the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:75–92.

13. Tomlinson, A, Khanal, S, Ramaesh, K, et al. Tear film osmolarity: determination of a referent for dry eye diagnosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4309–4315.

14. Luo, L, Li, DQ, Doshi, A, et al. Experimental dry eye stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines and MMP-9 and activates MAPK signaling pathways on the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4293–4301.

15. Haynes, RJ, Tighe, PJ, Dua, HS. Antimicrobial defensin peptides of the human ocular surface. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:737–741.