6 The Team

In this chapter we focus on the development and structure of teams, a major feature of the care that is provided to children with life-threatening illnesses and their families. We do so with the caveat that the literature on teamwork in pediatric palliative care is rather limited.2,3 Conspicuously absent are systematic empirical studies of how teams develop and operate and their effects on team members, patients, families, institutions, and communities.4,5 The literature that does exist is descriptive and of varying depth and breadth.4 Articles that deal with teams focus on the educational background of professionals who make up the team, their roles, and responsibilities.6 With few exceptions little attention is given to team development, team functioning, and team support in the face of serious illness and death.7–10 The purpose of this chapter is to draw attention to these issues in order to enhance our understanding of the team’s role in the care of children with life-threatening illnesses and determine what is needed to ensure the highest quality of care. Also, we hope to point the way toward further research and training.

Our discussion and recommendations are rooted in a relationship-centered approach that focuses on relationships among children, adolescents, and families who receive care services, and professionals who offer them. Such an approach recognizes the reciprocal influence between children and families on the one hand, and professionals, teams, and organizations on the other. These professionals, affected by their interactions, seek creative ways to contain, reduce, or transform suffering, and in so doing enhance the quality of care for a child who may never grow into adulthood.9,11,12 In other words, the relationship-centered approach is concerned with the establishment of relations that are potentially enriching, and are rewarding for all involved. Achievement of this goal requires understanding not only the patient’s and family’s subjective views and experiences so as to provide them with appropriate care, but also the professionals’ and team’s subjectivity, which shapes interactions with children and parents, and affects the quality of services.

Team Development

A dynamic, non-linear process

For a group of people to become a team they must share a common purpose, be strongly committed to the achievement of specific tasks, and value teamwork through which they expect to accomplish more by cooperating. Setting a clear task that is owned by each member and sharing outcomes are central to the transition from a group to a team.13

Another characteristic that distinguishes groups from teams is their size and leadership.13 While groups vary in size, teams contain no more than a few members who share leadership in clinical practice, although at an administrative level they are led by a senior member. Depending on a child’s condition and family’s situation, for example, different professionals may take the lead at any time and make a special contribution in order to achieve the team’s goal and tasks. Regardless of whether the team uses a manager to facilitate the coordination of actions or it chooses to be self-managed, the importance is that responsibility for outcomes be shared. By contrast, in a group, leadership is assigned to one person who imposes his or her leadership style that usually remains unchanged despite the changing focus or work activity.14

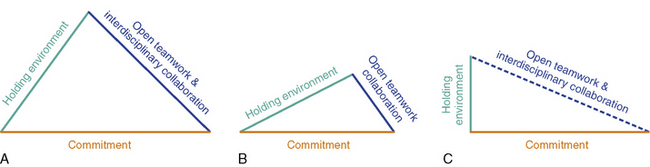

Among the available models for understanding team development, and especially applicable to palliative care, are those proposed by Papadatou and Morasz.9,15 They take the position that over the course of development, team members experience periods of co-existence, mutual acknowledgment and parallel collaboration, and of collaborative alliance with concomitant changes in disciplinary boundaries7,9,15,16 (Fig. 6-1).

Fig. 6-1 Dynamics of Team Development.

Redrawn from Papadatou, D. In the Face of Death: Professionals Who Care for the Dying and the Bereaved, New York, Springer Publishing; 2009.)

For a collaborative alliance to develop, care providers must spend time working together, sharing experiences, exploring different points of views, and developing a common language that does not exclude any member. Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teamwork require interdependent collaboration and are possible only if the team functions as an open system that makes use of relevant information. Relevant information is any information that helps members to understand how they operate as a system, how they manage suffering and adversities, and how they make use of their resources.9,17 Such information helps team members learn from experience, consider alternative ideas and coping patterns, embrace new initiatives, take risks, implement changes, and grow as a team. Unless there is opportunity to share information about what is happening in the day-to-day work, how things are accomplished, and how professionals think, feel and behave, team members cannot be in control of the quality of services they provide, and the system cannot be self-correcting.18 Such openness is not simply limited to the disclosure and airing of feelings and thoughts, but demands a reflective openness that enables team members to challenge their own and others’ thinking, suspend a sense of certainty, and share experiences with a receptiveness to having them challenged or changed.16,19

Organizational culture and context

A team’s development is not solely determined by its members.9,20 The social and organizational context in which it provides services has a major impact on how it develops and functions. For example, in some places pediatric palliative care services are delivered by teams in the community through home, respite, or hospice programs.21–24 In others, they are introduced in the hospital and offer consultation services to professionals, families, and other teams.4,25 In many countries that lack resources or are reluctant to acknowledge the needs of dying children and grieving families, palliative care teams are either non-existent or encounter major social, institutional, and legal obstacles in the provision of interdisciplinary services. Even in resource-rich countries that acknowledge the needs of dying children and grieving families, provision of interdisciplinary and palliative care services may be hampered by the country’s healthcare system.

Teams at Work

Indicators of team development, functionality, and effectiveness

We take the position that teams are active and dynamic systems with potential to change, develop, and grow. Teams, like the individuals who compose them, are not passive agents. Teams, like their members, are active agents who both shape and are shaped by their individual and collective responses to life-threatening illnesses, loss, suffering, and those whom they encounter in their work. Teams, like their members, are both subject to and react to internal and external stressors associated with the care of seriously ill patients and their families. Affected by the wider social and organizational context of work, team members, consciously or unconsciously, decide how to operate and collaborate with each other in order to meet the challenges of life-and-death situations. The team’s development, functionality and effectiveness are reflected in the patterns by which its members manage team boundaries and team operations as well as suffering and time.9

Experience and Management of Time

When a child’s life is threatened by a serious condition, time is perceived and experienced in unique ways by families and by care providers.26 A team that paces its work encourages children and their families not only to reflect on and work through their grief, but also to live a life that is meaningful to them. Such a team also takes the time to process work-related experiences that evoke anxiety in team members. The team learns from the past, integrates knowledge into the present practice, and strives toward future goals that aim at increasing the quality of the services it provides. In contrast, teams that avoid difficult subjects and experiences stagnate. Those teams become unable to take action, make decisions, and effect interventions. They delve into apathy and inertia. They become frozen in time. Some teams act as if time could be eliminated. They do too much; perhaps to avoid difficult issues such as case overload, loss, or death. Time is experienced as event-full. Work is driven by events or crises. An ongoing over-agitation prevents the team from slowing down in order to process its experiences and use relevant information for learning, changing, and growing.9,17

Teams and Families

A partnership in care

Most parents want to assume a central and active role in the care of their ill child. They acquire in-depth knowledge of the child’s condition and treatments, and develop appropriate skills in order to meet their complex needs.27,28 Parents of seriously ill children are faced with challenges and crises that are different from anything they have ever encountered in their lives.27 In their desire to be effective in this new parenting role, they have to interact with the professionals who can help them develop strategies and skills in order to manage present situations and anticipate future needs in both their sick and healthy children.27,28 This close involvement often leads to the erroneous assumption that parents are members of the team. Contrary to some clinicians who have written about teams and palliative care, we take the position that parents and patients are not members of the team.8,29

In this partnership, children’s views, concerns, and desires must be considered and approached with sensitivity and skill. This requires awareness of the differences in the ways children express both directly and symbolically, their physical, psychosocial and spiritual needs, preferences, and concerns; children and parents’ positions in the family; the rights, duties, and obligations each has to the other; and the impact of team’s actions on the patient’s and parents’ futures.30

Teams that experience difficulties with various aspects of boundary maintenance, goal setting, or time management are more likely to establish enmeshed or avoidant relationships with the patient and family.9 An enmeshed relationship develops when both the team and the family are unable to contain suffering, as well as the threat or reality of death. They become one, and remain undifferentiated, sometimes even after the child’s cure or death. For example, a team may need families that adore and glorify it, while at the same time some families need the team to maintain the memory of their deceased child to avoid moving on with life. An avoidant relationship between a team and a family, on the other hand, transforms their partnership into a strictly bureaucratic affair, a consumer-provider business that aims to manage practical issues without addressing the emotional and spiritual aspects of living with a life-threatening illness. Avoidant or enmeshed relationships are often reflective of the team’s and family’s inability to effectively manage the challenges of living with or dying from a life-threatening illness.

Teams Working Together

Principles, practices and particular challenges

It is common for pediatric palliative care teams to collaborate with a range of other professionals and teams. These include teams who specialize in specific disease-directed intervention (such as cystic fibrosis team, oncology team, neuro-muscular team), those that perform organ transplantations, or critical care interventions, and also those involved in day-to-day care such as home care teams, community care teams, hospice and educational teams. Palliative care teams also work closely with mental health and bereavement specialists who provide counseling services to family members. These parallel collaborations with other professionals, teams, organizations and services are vital to pediatric palliative care, however they require good communication, planning, mutual respect, and an approach that has been described by Payne as “open teamwork,” discussed below.31

Although all of these teams may recognize that other teams are also necessary for meeting the complex needs of children with life-threatening illnesses and their families, the particular problems that each addresses and the roles that each assumes may overlap. Exactly who delivers which aspects of care may also vary over the course of the child’s illness. For example, the oncology team may include in their domain issues of pain and symptom control as well as the child’s and family’s social and emotional needs during treatment with curative intent. However, as the disease progresses and the possibility of death emerges, the oncology team may see the responsibility for pain and symptom control as well as meeting the social and emotional needs of the child and family as falling more within the purview of the palliative care team. The child and parents may not perceive or desire this dichotomy at all, and want the services that each team offers to continue simultaneously.28,32 Hence, it is essential that all teams involved in the care of these children and families be committed to an agreed-philosophy, which also acknowledges the families’ choices. Often families’ preferences are for an approach that integrates disease-directed care along with treatment of symptom-directed and supportive care.28,33,34

Like families, all teams caring for children with life-threatening illnesses are confronted with the possibility of the children dying. While disease-directed teams may spend more of their energy against death, it would be wrong for these teams to proceed as if the possibility were not an eventuality for many of the patients they treat. Similarly, while palliative care teams accept childhood mortality as inevitable in some cases, and acknowledge their limitations in reversing a terminal disease, they cannot proceed as if battling the disease is not present in the minds of some team members, other teams they work with, or the patients and families. All must resist declarations such as “Things may get better tomorrow,” or “There is nothing we can do.” Instead, teams need to work with families to contain a suffering that is inevitable when life is seriously threatened and death becomes imminent, to address their needs and concerns during the most stressful period of their lives and to accept the reality before them.9

While the alleviation of suffering remains a priority, it can never be eradicated. At diagnosis, at each relapse of the disease, with each sign of physical deterioration, and particularly during the terminal phase, the family experiences a grieving process that is intense and often chronic.35 All teams who work with these families must acknowledge that suffering cannot be fixed with quick solutions and pre-determined interventions. Patients and families must be assisted in coping with their losses and grief, and in building resources and resilience that will enable them to live through the disease as well as after the child’s death.

The Team’s Ability to Function with Competence

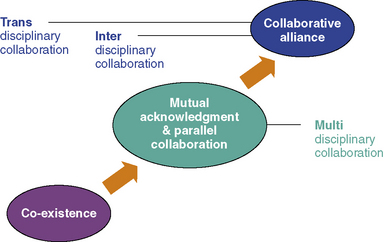

All teams confront a number of challenges in the uncertainty and grief that mark the experiences of the children and families. Teams mobilize various patterns to cope with the anxiety and suffering these realities evoke. Functional patterns are most likely to occur when three basic conditions are present. These are a commitment to clearly define goals and tasks and to a team member’s co-workers, a holding environment for children, adolescents, families, and care providers, and open teamwork through interdisciplinary collaborations.9

Commitment

One of the challenges in caring for children with life-threatening illnesses is that teams strive to achieve ideal or unrealistic goals of excellence.36 Realistic goals acknowledge the limitations of what care providers and teams can offer. For example, sometimes death cannot be avoided, nor life prolonged. At times, despite the best efforts of all involved, the dying trajectory is painful. There are also times when death occurs under traumatic conditions or the impending reality of death is not being dealt with by the family. Even though it is crucial for a team to work toward ensuring a dignified life for the entire family, and a dignified death for the patient, in reality there is only one thing that care providers can promise: the availability of a relationship. In that relationship, they will remain present, available, and able to introduce continuity in the midst of loss, separation, and suffering.

A commitment to co-workers and to the team is necessary to achieve the desired goals and to form an ethos of collaboration and of mutual support among team members. Professionals often experience grief and suffering while working with children with life-threatening illnesses. Acknowledging the professionals’ pain, and doing something about it, implies the sharing of personal experiences among team members who assume the responsibility to care for themselves as well as for each other. When committed to co-workers, they display care and concern through holding behaviors and mutual support.9,36–39

Holding behaviors involve acts of care, kindness, and support. Examples include listening to a colleague’s experiences and pain, offering feedback instead of advice and therapy, or standing by a co-worker during distressing times. Such behaviors are essential in establishing a culture of mutual support. Mutual support is marked by:9,37

It is important to note that while all types of mutual support are essential, the form that the support takes must be responsive to the needs and preferences of care providers, which vary at different times. Mutual support has been found to be a factor that determines professionals’ degree of job satisfaction.40–42 Studies indicate that one of the primary factors that contributes to professional burnout and turnover is not the team’s confrontation with multiple child deaths, however distressing, but rather the team’s inability to support its members.40–42 Committed care providers are devoted to meaningful goals and tasks, and rely upon one another to achieve the goals while providing mutual support through the process of care giving.

Holding environment

The concept of holding environment was first proposed by Donald Winnicott, an English pediatrician and psychoanalyst who described the significant role played by parents in providing their infant with effective care, which contributes to the child’s psychosocial development.43 Parents create an environment with safe boundaries that provides the infant with a sense of protection from the external world. In this environment parents cultivate a sense of order, continuity, and predictability that eventually helps the child to move from the safety of the parental relationship to the external world, which is gradually assimilated and to which the child adjusts.

In a parallel way, the team cultivates in families a sense of safety, order, predictability, and continuity, all of which are critical in times of crisis, ambiguity, uncertainty, and loss. However, such a team must also provide its members with a similar environment by creating a safe organizational space in which stresses, conflicts, suffering, and hopes associated with the challenges of caring for children with life-threatening illnesses can be worked out. This is important, because professionals can more effectively hold children and families through a serious illness when they are themselves held by their team and organization.44

Repeated encounters with death can deplete a team’s resources and leave professionals alone to manage their pain and suffering.39,42 When a holding environment is in place, care providers can feel safely overwhelmed by experiences, acknowledge, and accept their suffering as natural, and lean temporarily upon others who understand, validate their feelings, and have faith in their abilities to manage work challenges. In a paradoxical way, being securely attached and held by others enables team members to be self-reliant.38 Intra-team relationships are characterized by mature dependence, and are marked by a collective healthy respect for autonomy and for relatedness.39

A holding environment fulfils five important functions for team members:9

Assessing the Team’s Ability to Function with Competence

Teams are systems that are constantly changing and evolving. Acknowledging that their competence is enhanced by working conditions that promote commitment, a holding environment and open teamwork, can help professionals determine which among these conditions are well-developed and which require the team’s attention and further enhancement. Ideally, the development of all three conditions form an equilateral triangle with a base representing commitment to a philosophy of care, to clearly defined goals and tasks, and to each other. According to Ketchum and Trist, “commitment to work is central to people’s lives.”45

It becomes obvious that the described conditions are closely interrelated, and that the development of one enhances the development of the others (Fig. 6-2, A).

The following figures represent difficulties experienced by two teams in developing work conditions that ensure competence. In one pediatric palliative care team (Fig. 6-2, B), the professionals are committed to well-defined goals and tasks, and are supported in a holding environment in which they feel relatively secure to share cases and talk openly about their emotional responses, misgivings, or mistakes. Rather than going through suffering alone, team members draw on the experience and feedback of their colleagues. However, in the team described here, there is a gap between the need for nurturing and mutual support and the existing holding environment which, although in place, is not fully developed. As a result, team members engage in limited risk-taking because they feel uncertain that their team will hold them in times of high distress or crisis. The shorter line of open teamwork reflects the team’s tendency to avoid or restrict collaborations with other professionals in the larger organization and community. This affects families, who are deprived of valuable services, and care providers, who rely solely on their resources, with both becoming secluded into a cocoon-like environment. While this environment provides them with a relative sense of safety and protection, it concurrently marginalizes them from the rest of society.

Fig. 6-2, C, illustrates the working conditions of another pediatric care team, which remains too open and too permeable to collaborations with other professionals and teams without securing the boundaries of a holding environment, as indicated by the dotted line. This hampers the team’s ability to process experiences, frustrations, conflicts, and emotions resulting from its members’ interactions with others. Information that goes out from the team and information that is introduced into it is not used effectively to benefit families and team members. If team goals, tasks, and practices are not reviewed, enhanced, or changed, commitment to them, although strong, remains rigid. Concurrently, commitment to colleagues and co-workers is circumstantial and depends from the nature of collaborations that develop within or outside the team, at a given time.

The internal space of the triangles in Figs. 6-2, B, and 6-2, C, is limited by comparison to the space in Fig. 6-2, A, and graphically represents the limited opportunities of these teams to develop and use their resources in order to develop their competence.

Directions for Research, Education, and Practice

Useful resources for the development of materials and programs include: Children’s Project on Palliative/Hospice Services (The ChiPPS Project) sponsored by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Association; IPPC (The Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care) sponsored by the Education Development Center, Inc.; and End of Life Education for Nurses-Pediatric Palliative Care.4,46–48

Educational and training programs, like teams themselves, need to be evaluated. Tools for assessing palliative care curricula are starting to be developed, but work needs to expand to other disciplines and other types of programs.4 We would recommend instruction in methods for evaluating the team’s role in service delivery that could be used by teams in the course of their work with one another.

These methods also could be used to evaluate the short-term and long-term effects of new or current team practices, such as support groups, debriefing, and away days. They could also provide an evidence base of the sustainability or termination of such practices. The need for research on interventions that aim to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout has been underscored by a variety of researchers and clinicians.4

Summary

Caring for children whose lives are threatened and attending to the needs of grieving family members is important, strenuous, enriching, and rewarding work.4,42,49–52 Attending to how we care for families and for each other, can only enhance our practice, our lives, and the lives for whom we care.

1 Hron M. Oran a-azu nwa: the figure of the child in third-generation Nigerian novels. Res African Lit. 2008;39:27-48.

2 McCulloch R.E., Comac M., Craig F. Paediatric palliative care: Coming of age in oncology? Med. 2008;44:1139-1145.

3 Morgan D. Caring for dying children: assessing the needs of the pediatric palliative care nurse. Pediatr Nurs. 2009;35:86-90.

4 Liben S., Papadatou D., Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas [see comment]. Lancet. 2008;371:852-864.

5 Holleman G., Poot E., Mintjes-de Grot J., van Achterberg T. The relevance of team characteristics and team directed strategies in the implementation of nursing innovations: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009. 10.101/j.ijnurstu.01:005

6 Hubble R.A., Ward-Smith P., Christenson K., et al. Implementation of a palliative care team in a pediatric hospital. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23:126-131.

7 Connor S. Hospice and palliative care: the essential guide. New York: Routledge, 2009.

8 Jassal S.S., Sims J. Working as a team. In: Goldman A., Haines R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative care for children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

9 Papadatou D. In the face of death: professionals who care for the dying and the bereaved. New York: Springer, 2009.

10 Rushton C.H. A framework for integrated pediatric palliative care: being with dying. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:311-325.

11 Beach M.C., Inui T., the Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. relationship-centered care: a constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:53-58.

12 Report of the Pew-Fetzer Task Force on Advancing Psychosocial Health Education. Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care. San Francisco, Calif: Pew Health Professions Commissions, 2000.

13 Speck P. Team or group—spot the difference. In: Speck P., editor. Teamwork in palliative care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006:7-23.

14 Belbin R.M. Beyond the team. Buttersworth-Heinemann, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

15 Morasz L. Le Soignant Face a la Souffrance. Paris: Dunod, 1999.

16 Larsen D. The helper’s journey: working with people facing grief, loss, and life-threatening illnesses. Champaign, Ill: Research Press, 1993.

17 Ausloos G. La Compétence des Familles: Temps, Chaos, Processus. Ramonville, Saint-Agne: Erès, 2003.

18 Steele F. The open organization: the impact of secrecy and disclosure on people and organizations. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley, 1975.

19 Senge P. The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

20 Kaës R. Réalité psychique et souffrance dans les insitutions. In: Kaës R., Bleger J., Enriquez E., Fornari F., Fustier P., Roussillon R., Vidal J.-P, editors. L’Instituiton et Les Institutions: Études Psychanalytiques. Paris: Dunod, 2003.

21 Burne S., Dominica F., Baum J.D. Helen House: a hospice for children: analysis of the first year. BMJ Clin Res Ed. 1984;289:1665-1668.

22 Davies B., Collins J.B., Steele R., Cook K., Brenner A., Smith S. Children’s perspectives of a pediatric hospice program. J Palliat Care. 2005;21:252-261.

23 Steele R., Davies B., Collins J.B., Cook K. End-of-life care in a children’s hospice program. J Palliat Care. 2005;21:5-11.

24 Davies B., Steele R., Collins J.B., Cook K., Smith S. The impact on families of respite care in a children’s hospice program. J Palliat Care. 2004;20:277-286.

25 Rushton C.H., Reder E., Hall B., et al. Interdisciplinary interventions to improve pediatric palliative care and reduce health care professional suffering. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):922-933.

26 Sourkes B. Armfuls of Time: The psychological experience of the child with a life-threatening illness. Taylor & Francis: New York, 1996.

27 Bluebond-Langner M. In the shadow of illness: parents and siblings of the chronically ill child. NJ: Princeton, 1996. University Pres

28 Bluebond-Langner M., Belasco J.B., Goldman A., Belasco C. Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2414-2419.

29 Egan K. Patient-family value based end-of-life care model. Lergo: Hospice Institute of the Florida Suncoast, 1998.

30 Bluebond-Langner M., DeCicco A., Belasco J.B. Involving children with life-shortening illnesses in decisions about participation in clinical research: a proposal for shuttle diplomacy and negotiation. In: Kodish E., editor. Ethics and research with children: a case based approach. New York & London: Oxford University Press, 2005.

31 Payne M. Teamwork in multiprofessional care. New York: Palgrave, 2000.

32 Wolfe J., Wolfe J., Klar N., Grier H.E., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284:2469-2475.

33 Foster T.L. Pediatric palliative care revisited. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2007;9:212-219.

34 Field M.J., Behrman R.E. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: National Academic Press, 2003.

35 Monterosso L., Kristjanson L.J. Supportive and palliative care needs of families of children who die from cancer: an Australian study. Palliat Med. 2008;22:59-69.

36 Marquis S. Death of the nursed: burnout of the provider. Omega, Special Issue on Death, Distress, and Solidarity. 1993:17-34.

37 Papadatou D., Papazoglou I., Petraki D., Bellali T. Mutual support among nurses who provide care to dying children. Illness, Crisis & Loss. 1999;71(1):37-48.

38 Kahn W. Holding environments at work. J Appl Behav Sci. 2001;37:260-279.

39 Kahn W.A. Holding Fast: The struggle to create resilient caregiving organizations. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2005.

40 Vachon M. Occupational stress in the care of the critically ill, the dying and the bereaved. New York: Hemisphere Publishing, 1987.

41 Vachon M. Recent research into staff stress in palliative care. Euro J Palliat Care. 1997;4:99-103.

42 Papadatou D., Martinson I.M., Chung P.M. Caring for dying children: a comparative study of nurses’ experiences in Greece and Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:402-412.

43 Winnicott D.W. The maturational process and the facilitating environment: studies in the theory of emotional development. London: Karnac Book, 1990. (Originally published 1960.)

44 Papadatou D. Care providers’ response to the death of a child. In: Goldman A., Hain R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative care for children. Oxford Press: Oxford University, 2006.

45 Ketchum L.T., Trist E. All teams are not equal. London: Sage, 1992.

46 The ChiPPS Project (Children’s Project on Palliative/Hospice Services) sponsored by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Association. www.nhpco.

47 IPPC (The Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care) sponsored by the Education Development Center, Inc. www.IPPCweb.org..

48 End of Life Education for Nurses—Pediatric Palliative Care. www.aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC/Pediatric.htm. Accessed July 9, 2010.

49 Clarke-Steffen L. The meaning of peak and nadir experiences of pediatric oncology nurses: secondary analysis. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1998;15:25-33.

50 Davies B., Clarke D., Connaughty S., et al. Caring for dying children: nurses’ experiences. Pediatr Nurs. 1996;22(6):500-507.

51 Olson M.S., Hinds P.S., Euell K., et al. Peak and nadir experiences and their consequences described by pediatric oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1998;15:13-24.

52 Wooley H., Stein A., Forrest G.C., Baum J.D. Staff stress and job related satisfaction at a children’s hospice. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:114-118.