20 The teacher’s toolkit

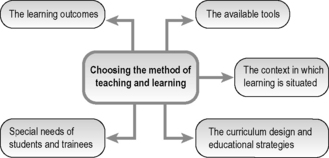

Choosing a teaching method

The FAIR educational principles (feedback, activity, individualisation and relevance) as described in Chapter 2, if applied in practice, result in effective learning. The creation of learning opportunities for students or trainees is the subject of this chapter.

It is useful to think about the choice of teaching method from different perspectives:

• The expected learning outcomes. Learning outcomes, as argued in Chapter 6, should be the starting point in any consideration of teaching.

• The tools to be used, for example simulated patients or PowerPoint presentations.

• The context or location where the learning is situated, for example the lecture theatre, the outpatient clinic or the rural community.

• The educational strategies adopted in the curriculum or course, for example problem-based learning.

• Special needs of the trainees or students, for example do they have different starting points in their abilities or mastery of the subject?

The teacher’s toolkit

• presentation tools such as PowerPoint to communicate ideas or principles particularly in a lecture context

• audience response systems (including simple coloured cards) to actively engage students in a lecture

• simulated patients and simulators to complement the use of real patients

• video clips to illustrate practical procedures

• podcasts or recordings of lectures

• games designed with an educational purpose

• online information sources and references

• computer-based learning opportunities such as virtual microscopy and interactive virtual patients

• networking tools such as Facebook to enhance collaborative learning

• peer-to-peer teaching where students support each other’s learning.

An account of the tools available to the teacher is provided in the chapters that follow.

Learning contexts

Classroom context

• The lecture theatre. Lectures have dominated many undergraduate courses. Their use and abuse are discussed later.

• Small group work. The value of small group teaching is now recognised along with the many advantages it offers. It is a key component of problem-based learning.

• Practical laboratory or anatomy dissection room. Traditional curricula provide learning opportunities in these locations. To some extent these have been replaced by alternatives including computer-based learning. (Methods used to teach anatomy are described in AMEE Guide No 41 by Louw and co-workers (2009).)

• Clinical skills centre. Centres or laboratories with learning opportunities using simulators and simulated patients are a feature in many institutions. The importance of access to such facilities across all phases of education is now recognised.

• Library, resource centre or computer suite. The library today is very different from the library as we knew it in the past. It now includes a range of multi-media resources in addition to books. There is access to a computer, and often areas are set aside for students to learn together.

Clinical context

• The hospital ward. Traditionally this has provided the context for much of a student’s clinical experience.

• Ambulatory care. With changes in hospital practice, ambulatory care and outpatient departments have provided an increasingly valuable component of a student’s clinical experience.

• Community. Today there is increasing emphasis on community-based education in order to provide a broader perspective on patient care. The value of teaching and learning in the context of rural health care has been recognised.

• Specialised settings. Experience in more specialised settings such as palliative care or stroke units can provide valuable learning opportunities.

Informal settings

Much of a student’s education takes place away from the lecture theatre, the tutorial room or the clinic. Students may learn at home and informally from each other. Today’s students are very different from those of previous generations. Networking and collaborative learning play an important part in their studies as described in Chapters 26 and 27.

Educational strategies

A range of educational strategies are described in Section 3. The strategy adopted has implications for the choice of learning method:

• In a problem-based curriculum, greater emphasis is usually (but not always) placed on small group work.

• In a community-based curriculum, learning takes place in a community, perhaps in a rural setting at a distance from the main education centre.

• In a vertically integrated curriculum, the use of simulations either in the form of simulated patients or simulators can introduce students effectively to clinical practice and practical procedures in the early years of their medical training.

• The use of a simulated ward may be valuable to support inter-professional learning.

The student or trainee

The learner should be kept sharply in focus when a learning method is selected. Think about:

• the number of students to be taught at any one time

• the background of the students and their individual needs

• the sophistication of the student in relation to new learning technologies

Each student is different with regard to how their learning needs can best be met – one size does not fit all. As far as possible, their individual needs should be taken into account when the learning method is selected (see also Chapters 2 and 13). Not all students will choose to attend a lecture, and many may prefer an alternative approach.

Keep in mind that students are not simply the recipients of the training or educational programme. They may be co-authors and contribute actively to its development and delivery. This is discussed further in the section on peer teaching (Chapter 27).

Reflect and react

Here are some thoughts to reflect upon in relation to your choice of teaching method:

1. There is no such thing as the single ‘best’ teaching method. Decide the best approaches for your students and trainees, taking into account the context and resources available.

2. Most teachers adopt teaching approaches with which they have gained experience and feel comfortable. Look again at your current approaches and consider whether you are using them to maximum effect. Are you sufficiently familiar with the range of methods available, including the new technologies such as simulation and e-learning, to allow you to make an informed decision about the best methods to be adopted in your situation? The descriptions in this book will assist you but it is particularly valuable if you can gain experience of the different approaches first hand at another centre or at an educational meeting. You should aim to harness in your teaching the best of new approaches alongside the best of existing proven methods.

3. Think about the different contexts in which the student or trainee can learn. Are you exploiting fully the range of contexts? In the undergraduate curriculum, for example, with the emphasis on more authentic learning, is sufficient emphasis being given in the early years to learning in the clinical setting and in the community? In the postgraduate curriculum, are sufficient opportunities provided for the trainee to work in a clinical skills centre or online?

4. Think about how you might offer a range of learning opportunities that match the needs of the individual student.

Louw G., Eizenberg N., Carmichael S.W. The Place of Anatomy in Medical Education. AMEE Guide No. 41. Dundee: AMEE, 2009.

A description of approaches to teaching anatomy.

McKeachie W.J. Teaching Tips. Strategies, Research and Theory for College and University Teachers, twelfth ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2010.