Chapter 2 The system of assessment and care of the primary survey positive patient

Introduction

Emergency situations cause stress, especially if they are unfamiliar or present new and different challenges. Specific life threatening medical emergencies may only be experienced by most practitioners a few times in their career1,2 and even experienced clinicians require training and practice to maintain confidence and skills. Using a system of care and assessment will improve consistency. This chapter aims to set out a system of assessment for the patient with emergency care needs. It can only offer a framework; proper application will require training, flexibility, common sense, and experience (Box 2.1).

Recognition of immediately life threatening problems

Most patients do not have an immediately life-threatening airway, breathing, circulation, or neurological problem. The patient who is talking normally, is fully orientated, is not pale or sweaty, has no dyspnoea, has a normal pulse, and is not breathless is unlikely to be in immediate danger. However the patient’s condition may change very quickly and some need careful monitoring and re-evaluation (for example, the patient with chest pain may have a sudden cardiac arrest). Making decisions about the presence or absence of an immediate threat to life can be difficult. There is evidence that important clinical signs of urgent airway, breathing, circulation, or neurological problems may be easily missed, misinterpreted, or mismanaged in the emergency setting in hospital practice;1,2 the risk of clinical errors in pre-hospital practice is likely to be greater.

Fortunately, there are common presentations for most acute medical emergencies that can be anticipated. These include shortness of breath, chest pain, abdominal pain, collapse, coma, and seizures (Box 2.2).

The primary survey positive patient

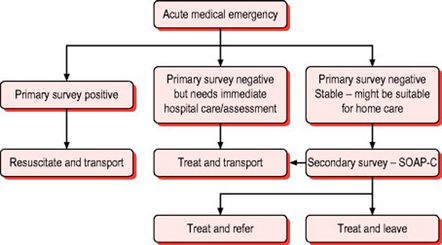

A number of excellent reference texts and resources exist describing the priorities and immediate actions for assessing acutely unwell patients in the hospital and general practice setting.3–10 The approach and techniques advocated are equally applicable in the resource limited community care environment and during transport to hospital. Similarly, the ABCDE approach taught on standard life support courses is as applicable to acute medical emergencies as it is to resuscitation from cardiac arrest and the management of major trauma. This structured approach is illustrated in Figure 2.1. This reflects the central doctrine of emergency care that immediate assessment and management of a life threatening condition does not require a precise diagnosis. It also illustrates the importance of considering early transport to definitive care with emergency treatment compared with resuscitation en route.

After ensuring the scene is safe, the practitioner should aim to undertake a rapid primary survey (Box 2.3). In many patients, the primary survey may be completed very quickly. The common pathways to cardiac arrest in acute medical emergencies are airway obstruction, respiratory failure, circulatory failure, and neurological failure. The aim of the primary survey is to seek out evidence of these in order to target specific resuscitative interventions.

Box 2.3 Rapid primary survey

Circulation Assessment

There is unlikely to be an immediately life threatening circulation problem if:

Detailed assessment of the circulation should identify the presence of shock and a systemic inflammatory response to infection. Shock is a failure of tissue oxygenation. The classic signs include prolonged capillary refill, tachycardia, tachypnoea, and sympathetic nervous system stimulation (pallor, sweating and peripheral vasoconstriction). ‘Sepsis’ refers to evidence of systemic infection (for example, pneumonia, meningococcal disease) accompanied by systemic inflammatory responses. These include a pulse rate greater than 90, a respiratory rate greater than 20, and a temperature above 38° C or below 36° C. Acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage may be missed if the clinical signs of bleeding are not assessed. Finally, assessment of the circulation in medical emergencies includes an assessment of heart rhythm and a search for evidence of heart failure and myocardial dysfunction (tachycardia, 3rd or 4th heart sounds, systolic murmur).

Patients with a serious illness requiring immediate transport to hospital

There are a number of common problems where the primary survey may confirm that the patient is ‘stable’ but they may still have a condition that needs immediate treatment, usually in hospital. Chest pain, vascular occlusions, severe shortness of breath, severe abdominal pain, and acute neurological deficit are examples. In such cases the focus of treatment is rapid transport to hospital with any necessary interventions being provided during the journey.

The secondary survey

The SOAPC system

The system that we have adopted (Box 2.4) is based heavily on problem oriented methodology:11

Objective information: examination findings, augmented when appropriate, by investigations and information from the patient record (for example, electronic record or patient held records)

Objective information: examination findings, augmented when appropriate, by investigations and information from the patient record (for example, electronic record or patient held records) Analysis: your opinion as to the probable cause of the problem and whether other serious problems need to be ruled out

Analysis: your opinion as to the probable cause of the problem and whether other serious problems need to be ruled out Plan: the further care of the patient including advice, treatment with drugs, whether the patient requires another healthcare facility or can stay at home with appropriate follow up and ‘safety net’ advice

Plan: the further care of the patient including advice, treatment with drugs, whether the patient requires another healthcare facility or can stay at home with appropriate follow up and ‘safety net’ adviceS – The subjective assessment

The history is the key to correct patient assessment.13 When errors are made, they are usually attributable to inadequate history taking. It is not possible or desirable to probe every part of the patient’s medical history. Instead it is important to have a system that obtains key information. A much more detailed history will be needed in the patient who is likely to be treated at home than the patient who is going to be transported to hospital. Box 2.5 sets out the main parts to history taking.

The history of previous episodes may give important pointers to the diagnosis and treatment.

O – The objective assessment (examination and tests)

Vital signs

Pulse, blood pressure, temperature, conscious level and oxygen saturation are all easy to measure and provide objective proof of the patient’s physiology at the time of the examination. Some might argue that a full set of vital signs is not required in cases of minor illness, but the situation can change and it is good practice to take baseline recordings, especially if the patient is unwell. Records of vital signs are also evidence of completion of an appropriate primary survey.

Respiratory system

Use the look-feel-listen system (Box 2.7).

Look – Measure the respiratory rate and assess if the patient has any difficulty in breathing. Look for tracheal tug, the use of accessory muscles (Fig. 2.2), or in-drawing of intercostal muscles. Assess if the patient is becoming exhausted and look for excess sputum production, inhaler or home nebuliser use.

Feel – Is the chest expansion the same on both sides (Fig. 2.3)?

Fig. 2.3 Demonstrating chest expansion. Note the thumbs are held above the chest wall. This makes movement more obvious.

Listen – Check the percussion note (Fig. 2.4) and listen to the breath sounds on both sides at the apex, in the axilla and posteriorly at the top, middle and base (McGill virtual stethoscope, http://sprojects.mmi.mcgill/mvs/mvsteth.htm). The aim of auscultation is to determine whether air entry is normal and equal on both sides. Normal sounds are described as vesicular. If the lung is solid, sound transmission is different and the noise is similar to the sounds heard when the stethoscope is placed over the trachea (bronchial breathing). The next step is to assess if there are added sounds, these can be wheeze (inspiratory, expiratory or both) or crackles.

Cardiovascular system

Look – Is the patient pale? Are they sweating? Is the skin clammy? Is skin turgor normal? Look in the mouth – are the mucous membranes dry? Check the neck veins – are they full or collapsed? Check the jugular venous pulse (Fig. 2.5).

Feel – Check capillary refill time. Note the pulse rate and rhythm and character. Feel for peripheral pulses (Fig. 2.6). Look for ankle oedema. Check the calves for tenderness and swelling.

Gastrointestinal system

All books of surgical examination emphasise the importance of exposing the whole abdomen, including the genitalia. In the community setting the same principle applies but it can be difficult to do this because of facilities and lack of a chaperone. If conditions do not permit a full examination then it is important to recognise that examination is incomplete. Rectal examination and vaginal examination are even more problematic. Without adequate patient consent, privacy and a chaperone these examinations should not be undertaken except in life threatening situations.

The abdomen is examined using the ‘look-feel-listen’ system.

Feel – gently at first to try to detect any rigidity in the abdominal muscles. If there is inflammation of the peritoneum then the overlying muscles will protect the area, this is known is guarding. Identify the areas of maximum tenderness. Another sign of peritoneal irritation is percussion tenderness. Place fingers over the area of tenderness and percuss these with fingers of the other hand (Fig. 2.7). Pain during this test is indicative of peritoneal irritation.

Central nervous system screening exam

If the patient is lucid and able to give a full history and walk normally, can hold their arms out steadily with their eyes closed (Fig. 2.8), can stand on each leg with eyes closed and has normal facial expressions and eye movements there is no severe neurological deficit. This screening test is not sufficient for anyone with a primary neurological complaint.

Record orientation in time, place and person and the Glasgow Coma Score. The Abbreviated Mental Test Score is more detailed (Box 2.8). It is especially useful in the older patient, particularly if there is access to previous records. Patients should be able to score 8/10.

The examination for the main neurological presentations can be tailored to suit the situation.

In the patient with sudden onset of headache (see ‘headache’ in Chapter 10) a full general examination is very important. Vital signs including pulse, blood pressure and temperature may give clues. There should be a full examination of the whole body looking for any signs of rash. Photophobia and neck stiffness should be sought (Fig. 2.9). Other signs such as muscle tenderness and Kernig’s signs may be checked.

Cranial nerve screening exam

CN 2 Assessment of vision should include acuity, visual fields by confrontation (Fig. 2.10), pupillary responses, and fundoscopy when required.

CN 2 Assessment of vision should include acuity, visual fields by confrontation (Fig. 2.10), pupillary responses, and fundoscopy when required. CN 5 Ask the patient to open the lower jaw against resistance of your hand. Check sensation over the forehead, cheeks and jaw.

CN 5 Ask the patient to open the lower jaw against resistance of your hand. Check sensation over the forehead, cheeks and jaw. CN 7 Look for symmetry when the patient screws up their eyes, frowns, raises eyebrows, shows their teeth, and puffs out their cheeks (Fig. 2.11).

CN 7 Look for symmetry when the patient screws up their eyes, frowns, raises eyebrows, shows their teeth, and puffs out their cheeks (Fig. 2.11). CN 8 Rub fingers together gently at each ear, asking the patient if they can hear and if there is a difference between ears.

CN 8 Rub fingers together gently at each ear, asking the patient if they can hear and if there is a difference between ears. CN 9/10 Ask the patient to open their mouth and to say ‘aah’. Assess the movement of the uvula. Check gag reflex. If there is no obvious deficit, assess swallowing by asking the patient to take a sip of water.

CN 9/10 Ask the patient to open their mouth and to say ‘aah’. Assess the movement of the uvula. Check gag reflex. If there is no obvious deficit, assess swallowing by asking the patient to take a sip of water.Peripheral nervous system exam

Muscle tone is assessed by flexing and extending the elbows, wrists and knees.

Muscle power – the initial screening test for muscle power of holding out both arms is described above (see Fig. 2.8). Then assess power in the major groups acting over major joints.

Sensation – use a blunt point to assess touch (special single patient use disposable points are available). Compare sensation in both limbs. Patients may be able still to feel something even if there is a sensory deficit. You are looking for a qualitative difference in sensation (Fig. 2.12).

Co-ordination can be assessed by the finger-nose test (Fig. 2.13).

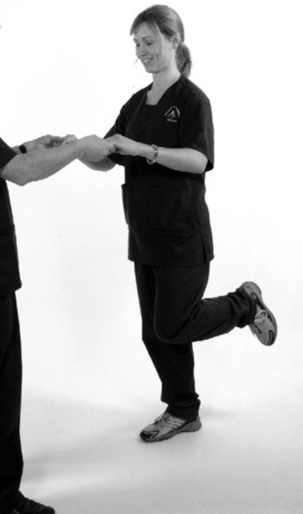

Balance is checked by asking the patient to stand on each leg with eyes closed. It is essential to hold the patient’s hands when doing this test and it may not be possible in many patients (Fig. 2.14).

Ear, nose and throat exam

ENT examination is an integral part of the examination of the unwell adult or pyrexia of unknown origin and especially the unwell child. Check the throat and tonsils, feel the neck for lymph nodes, and check the tympanic membranes. If the patient is complaining of difficulty in swallowing, observe them drinking some water. Full details are given in Chapter 11.

Musculoskeletal exam

The history will indicate if the problem is attributable to a recent injury or a non-traumatic problem. This is a very important distinction in a patient with musculoskeletal symptoms as the diagnostic range is very different. In the patient with no history of trauma you will need to consider if the pain is attributable to sepsis, ischaemic or vascular problems, or referred from the spine or heart/chest or abdomen.

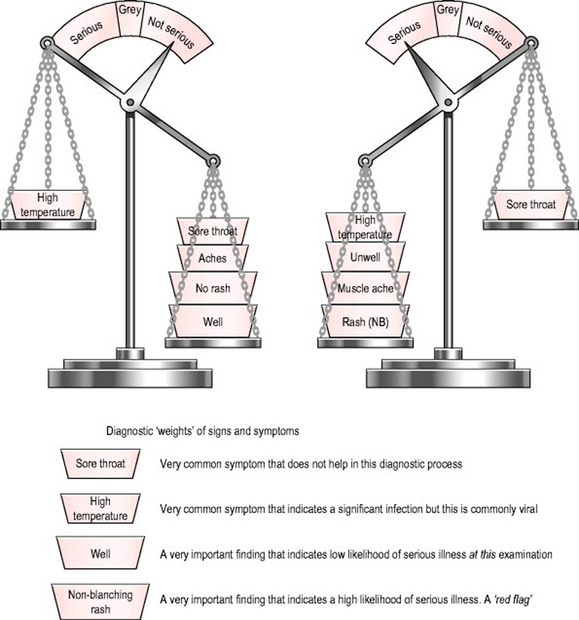

A – Analysis

Decision making and diagnosis are necessary evils. Necessary as it is not possible to decide on treatment without a working diagnosis, an evil because clinical decision making can be imprecise. A diagnosis is reached by a synthesis of the information you have. Each ‘bit’ of information will carry different weights. Some features, either in the history or examination, will carry so much weight that the diagnosis is easy (Fig. 2.15).

Group 2: some features or symptoms that might suggest a serious illness, needs further investigation, or a period of observation

Group 2: some features or symptoms that might suggest a serious illness, needs further investigation, or a period of observation Group 4: non-specific symptoms with no signs of serious illness at present; the patient may be treated at home, with advice to seek further help if symptoms get worse

Group 4: non-specific symptoms with no signs of serious illness at present; the patient may be treated at home, with advice to seek further help if symptoms get worse Group 5: no evidence of a new medical condition but concern about social support and ability to cope.

Group 5: no evidence of a new medical condition but concern about social support and ability to cope.If you are unsure about the diagnosis then a number of options will be available:

give initial treatment and advise the patient to seek advice if the condition does not follow the predicted course, if the symptoms get worse, or new symptoms develop.

give initial treatment and advise the patient to seek advice if the condition does not follow the predicted course, if the symptoms get worse, or new symptoms develop.P – Plan

Group 3 patients will be treated at home along local guidelines and patient group directions.

C – Communication

Communication with the patient and carers is vital. Check that they agree with your interpretation of the information provided. Ensure they understand your diagnosis and the treatment you are planning. Ask if they have questions. Make sure all understand what to do if the symptoms get worse or they do not improve as you predict. This process is called ‘safety netting’ (Box 2.9).

1 McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A, et al. Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ. 1998;316:1853-1858.

2 Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, et al. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324:387-390.

3 Avery A, Pringle M. Emergency care in general practice. BMJ. 1995;310:6.

4 Moulds AS, Martin PB, Bouchier-Hayes TAI. Emergencies in general practice, 4th edn. Reading: Librapharm, 1999.

5 Sprigings D, Chambers J. Acute medicine, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2001.

6 Advanced Life Support Group. Acute medical emergencies: the practical approach. London: BMJ Books, 2001.

7 Ramrakha P, Moore K. Oxford handbook of acute medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

8 Wyatt JP, Illingworth RN, Clancy MJ, et al. Oxford handbook of accident and emergency medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

9 Darwent M, Gregg R, Higginson I, et al. What to do in a general practice emergency. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 1997.

10 Greaves I, Porter K, editors. Pre-hospital medicine: the principles and practice of immediate care. Arnold, London, 1999.

11 Palmer KT. Notes for the MRCGP, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1998.

12 Hoffbrand BI. Away with the system review: a plea for parsimony. BMJ. 1989;298:817-819.

13 Fraser RC. The diagnostic process. Clinical method – a general practice approach, 3rd edn. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 1999.

14 Wardrope J, English B. Musculo-skeletal problems in emergency medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

15 McRae R. Clinical orthopaedic examination. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, 1997.

3rd edn. Fraser RC, editor. Clinical method – a general practice approach. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 1999.

Munro JF, Campbell IW. MacLeod’s clinical examination, 10th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Bouchier IAD, Ellis H, Fleming PR. French’s index of differential diagnosis, 13th edn. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1996.

Hopcroft K, Forte V. Symptom sorter. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1999.

Seller RH. Differential diagnosis of common complaints, 4th edn. Pennsylvania: WB Saunders, 2000.

Taylor RB. The ten minute diagnosis manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams, 2000.