CHAPTER 4 The Stiff Knee

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

Anatomy

Normal Knee Range of Motion

The knee has been described as having 6 degrees of freedom—internal-external rotation, compression-distraction, medial-lateral translation, abduction-adduction, anterior-posterior translation, and flexion-extension. Normal extension is 0 degrees, but some individuals may have slight hyperextension of up to 5 degrees. Normal knee flexion is 140 degrees in men and 143 degrees in women. Knee flexion up to 165 degrees is seen in certain groups.1 The functional range of motion for most activities of daily living is 10 to 120 degrees. Loss of knee flexion or extension can lead to significant disability and inability to perform simple every day activities. Studies looking at gait patterns have shown that 67 degrees of knee flexion is required in the swing phase of walking, 83 degrees to ascend stairs, 90 degrees to descend stairs, 93 degrees to rise from a standard chair, and 110 degrees to cycle upright.2

Potential Locations of Entrapment

Suprapatellar Pouch.

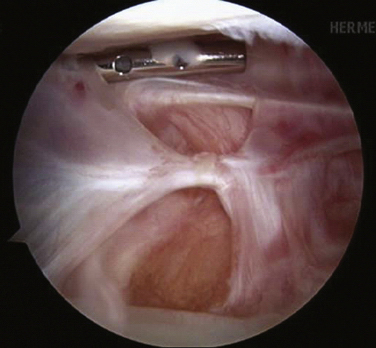

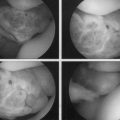

The suprapatellar pouch, also referred to as the suprapatellar bursa, is the superior continuation of the knee joint. This area is posterior to the quadriceps tendon and anterior to the femur. It continues on either side of the patella as the medial and lateral gutters. This area is covered by a synovial membrane. The suprapatellar pouch should extend 3 to 4 cm above the patella. It is the most common area of arthrofibrosis. With extensive scarring of the suprapatellar pouch, knee flexion is typically lost (Fig. 4-1). Terminal extension is usually not affected as much.

Medial and Lateral Compartments.

The medial and lateral compartments contain deep capsular ligaments and menisci. Loose bodies or bucket handle meniscal tears in these compartments may lead to restricted range of motion. It is important to evaluate these at the time of surgery and address any pathology found.

Anterior Interval.

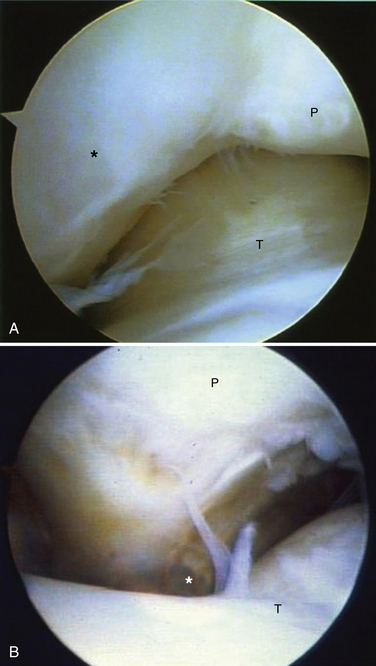

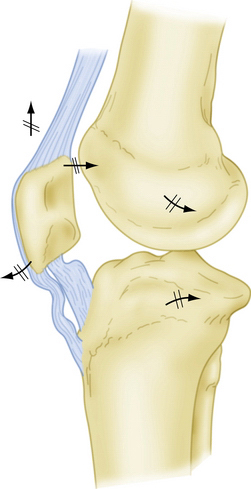

This potential site of entrapment includes the fat pad, patellar tendon, and retropatellar recess. The anterior interval is bordered anteriorly by the fat pad and patellar tendon, posteriorly by the intracondylar notch and anterior border of the tibial plateau, superiorly by the patella, and inferiorly by the tibial tubercle. The retropatellar recess is a space between the insertion of the patellar tendon and anterior border of the tibia. Extracapsular structures in this area include the medial and lateral patellotibial ligaments. These structures can become contracted, leading to progressive arthrofibrosis of the knee. When fibrosis and scarring occur in the anterior interval, the patella may be drawn inferiorly, creating patella baja. However, patella baja, or patella infera, may not always occur with arthrofibrosis unless a dense band of scar forms between the inferior pole of the patella and anterior aspect of the tibial plateau (Fig. 4-2). This pseudopatellar tendon can severely hinder knee motion and lead to patella tendon resorption. Loss of flexion and extension may be present in those patients with anterior interval involvement (Fig. 4-3).

Pathoanatomy

To treat arthrofibrosis successfully, the surgeon must identify the cause. Failure to indentify the cause and correct it will most likely lead to recurrence of the stiffness.

Potential Causes of Knee Stiffness

Immobility.

The effects of immobility, regardless of the cause, are always the same. Prolonged immobilization of the knee causes progressive contracture of the capsule and pericapsular structures. It also causes encroachment on the joint by fibrofatty connective tissue. The border between the cartilage and fibrous tissue may become indistinguishable. This can eventually lead to joint cavity obliteration. Pressure necrosis, erosion, and cysts occur where cartilage surfaces contact one another for prolonged periods. The subchondral plate is invaded by mesenchymal cells, destroying the deep cartilage layers.3

Ligament Reconstruction Technical Errors.

Every knee that has had surgery or injury demonstrates decreased knee motion and patella tightness as it progresses through the normal healing process. However, certain factors can increase the chances of arthrofibrosis. Malposition of tunnels for ligament reconstruction can lead to a stiff postoperative knee. With anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, if the tibial tunnel is too anterior, the graft will impinge on the roof of the notch, thus limiting extension.4 If the femoral tunnel is too anterior, the graft will become taught too early in flexion, limiting terminal flexion.5 Overtensioning of the graft during ligament reconstruction can overconstrain the knee as well.

Timing of Surgery.

Acute ligament reconstruction of the knee has been shown to have a higher incidence of arthrofibrosis than delayed reconstruction. Shelbourne and colleagues found a statistical difference in postoperative range of motion in patients who had ACL reconstruction performed within 1 week of the injury compared with those who had reconstruction 3 weeks after the injury.6 Harner and associates found the rate of arthrofibrosis to be 37% in the acutely reconstructed knee as compared with 5% of those who had delayed reconstruction.7 Others have found no difference in arthrofibrosis rates and surgical timing. Bach and coworkers found no difference in the range of motion between acute and chronic reconstruction.8 It is our opinion that the condition of the soft tissue dictates the timing of the surgery. If the patient has good active quadriceps control, near-normal preoperative range of motion, and no longer has a warm swollen knee, then surgical reconstruction may be undertaken safely, regardless of the time from injury.

Patient Factors.

Some patients are more prone to scar formation. Patients with genetic disorders such as scleroderma are predisposed to arthrofibrosis. Other patients may not have a specific genetic disorder but have a higher likelihood of forming fibrotic tissue. These fibrotic healers are at an increased risk for arthrofibrosis, regardless of other potential causes. They tend to produce keloid scars. Careful attention at the time of the history and physical examination may lead the surgeon to recognize patients who may be at a higher risk for the development of a stiff knee. Some research has focused on finding specific genetic alleles responsible for arthrofibrosis. Skutek and colleagues looked at 17 patients who developed arthrofibrosis after ACL reconstruction. They found that patients with arthrofibrosis were less likely to have allelic group HLACw*07 and more likely to have allelic group HLACw*08 on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci.9

Fat Pad Trauma.

Albert Hoffa, a German surgeon, first described a condition characterized by traumatic and inflammatory changes occurring in the infrapatellar fat pad in young athletes. These changes may lead to pain, swelling, and restricted motion of the knee. Hypertrophy of the fad pad may cause it to become entrapped between the tibia and femur. Catching of this hypertrophied fat pad may occur when the flexed knee is extended suddenly. If this condition persists for a significant period, fibrosis may develop.

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

One of the most important structures to examine in the stiff knee patient is the patella. The patella is the centerpiece of knee motion and is almost always involved in the stiff knee. Medial and lateral patella glide should be assessed. Medial and lateral patellar tilt should be measured and compared withthe contralateral side. Decreased medial or lateral tilt compared with the contralateral side is suggestive of medial or lateral gutter involvement. Anterior patellar tilt should also be assessed (Fig. 4-4). If the patient has infrapatellar entrapment, he or she will usually lose the anterior patellar tilt. With moderate to severe infrapatellar entrapment, the patient will usually develop a shelf sign, which denotes loss of the retropatellar tendon bursa and adherence of the patellar tendon to the tibia (Fig. 4-5).

Diagnostic Imaging

A standard series of radiographs should be taken on initial evaluation of the stiff knee. Weight- bearing anteroposterior and 45-degree anteroposterior flexion views should be obtained to assess for any degenerative changes. Bilateral 30-degree lateral views should be obtained to evaluate for any degenerative changes as well as any patella baja. A Merchant or sunrise view of the knee should be obtained to evaluate patella tracking as well as any patellofemoral degenerative changes. Long leg alignment or scanograms should be obtained if any significant varus or valgus malalignment is suspected. Computed tomography and ultrasound have little use in the evaluation of the stiff knee, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be of some benefit. A MRI scan can evaluate the structures within the knee, including the location and integrity of any previously reconstructed ligament. It can also help quantify the degree of any cartilage loss or injury. Loose bodies within the intracondylar notch will be evident by MRI. An MRI scan will give a detailed evaluation of the fat pad, which may have contracted, calcified, or formed a pseudotendon (Fig. 4-6).

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

It is important for the surgeon to understand the indications and contraindications for arthroscopic or open lysis of adhesions (Box 4-1). The most common mistake is to operate too soon on a stiff knee. Although short-term range of motion may improve, this second hit only worsens the arthrofibrosis in the long run. The knee must not be warm and swollen when proceeding with any treatment. It may take from 2 to 12 months before the knee has returned to a noninflamed state. Regardless of the cause, the quadriceps muscle must be contracting normally prior to proceeding with surgery. If the patient does not have adequate quadriceps strength to maintain extension after the surgery, the procedure will have a poor outcome.

Box 4-1 Indications, Contraindications, and Relative Contraindications for Treatment

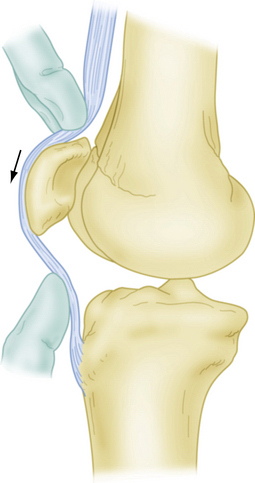

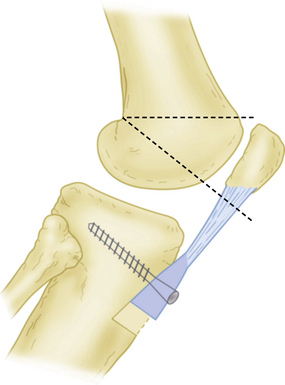

Infrapatellar entrapment is an extremely difficult condition to treat arthroscopically. Although a mild degree of infrapatellar entrapment may respond to arthroscopic release, moderate to severe cases usually require an open release, with or without a retropatellar interposition patch. To correct patella infera, elevate the patellar tendon away from the anterior tibia, and restore the alpha angle, it is sometimes necessary to move the tubercle both superiorly and anteriorly. The DeLee-Paulos osteotomy is designed to accomplish this. A large shingle of anterior tibia (including the tubercle) is created. A 5-mm deep cut is made above the tubercle. A second 15-mm deep cut approximately 3 cm distal to the tubercle is also made. These two cuts are connected medially to laterally and the bone fragment is then moved superiorly, enough to correct the patella baja. As the bone fragment moves superiorly, it automatically proceeds anteriorly. It is fixated with one to two screws. The defect created by the osteotomy is then bone-grafted (Fig. 4-7).

Conservative Management

Prevention is the best treatment for arthrofibrosis. Range-of-motion (ROM) exercises should be initiated as soon as possible after surgery. Other postoperative measures that can be taken to prevent stiffness include immediate quadriceps exercises, patellar mobility exercises, and obtaining early extension. Once arthrofibrosis has occurred, conservative treatment is based on the degree of involvement. Mild to moderate motion loss is treated initially with more active and passive ROM exercises, patellar glides, anti-inflammatories, analgesics for pain control, and extension bracing at night. If moderate to severe motion loss is present, it is critical to stop any painful treatments. Painful aggressive therapy at this point will only worsen the problem. A tapered dose of oral steroids may also be used for those who do not have contraindications. Muscle stimulation may be used and can be helpful. The most important part of this waiting period, during which the knee is still swollen and warm, is to avoid aggressive physical therapy and forceful manipulation. Swimming and cycling are activities that may be started during this time, with low risk of worsening the vicious cycle of pain, inflammation, and stiffness.

Arthroscopic Technique

Before considering surgery, the patient must have minimal swelling, no warmth, improving pain, and good quadriceps function. Common findings at the time of surgery usually include degeneration of the articular cartilage, abundant fibrous tissue, soft tissue transformation, and patella infera.10 The surgeon must be prepared to address these at the time of surgery if found.

Anesthesia

In the ideal situation, the patient is placed under general anesthesia with a regional nerve block and indwelling catheter. This allows for good pain control postoperatively, resulting in better patient compliance with immediate postoperative rehabilitation. An alternative strategy is to use epidural anesthesia with an epidural catheter for intraoperative and postoperative pain control.11

Capsular Distention

We use a similar technique as described by Millett and Steadman.12 We distend the capsule initially with 60 mL of normal saline through a superolateral injection. Fluid should follow easily into the suprapatellar pouch. If resistance is felt, the needle is redirected until the knee is easily distended. An additional 60 mL of normal saline is then injected slowly to allow for some additional distention of the contracted capsule.

Locations of Entrapment

Suprapatellar Pouch.

It is important to examine the suprapatellar pouch for adhesions (see Fig. 4-1). Use electrocautery to lyse any adhesions or plica seen. If the suprapatellar pouch appears to be small, then scar tissue has likely encroached on the superior part of the pouch. It may be necessary to débride the superior part of the pouch with an arthroscopic shaver. The pouch should extend at least 3 cm proximal to the patella. If significant débridement using the arthroscopic shaver is required, we recommend cauterizing the tissue afterward to achieve hemostasis.

Medial and Lateral Gutters.

As with the suprapatellar pouch, the medial and lateral gutters should be inspected. Lyse any adhesions visualized in this area with electrocautery. Typically, the adhesions will form between the capsule and femoral condyle. If the medial or lateral patellofemoral ligament is contracted, release of these ligaments is usually required. If limited medial glide and lateral patellar tilt are present on physical examination, we usually proceed with a lateral retinacular release. Starting at the inferior aspect of the vastus lateralis, the lateral release is performed using an electrocautery hook. The release is carried down to the level of the anterior lateral portal site. Once the release is complete, the patella should be able to be tilted 45 to 70 degrees. Additionally, the patellotibial ligament may require release distal to the lateral portal. If limited lateral glide and limited medial tilt are present, a medial release may be performed as well.

Infrapatellar Area.

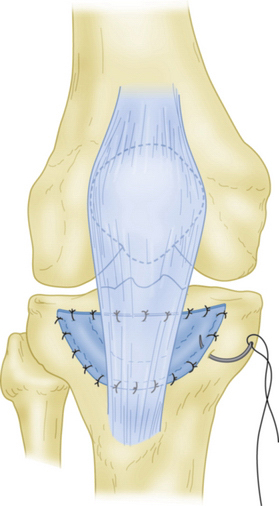

Inspection of the fat pad should be performed. In severe arthrofibrosis, a dense wall of scar may be present, making it difficult to visualize the fat (see Fig. 4-2). The fat pad should never be fully resected. The fat pad should be released using electrocautery on the medial and lateral sides. It is also important to release scar and the fat pad from the anterior tibia. In a normal knee, a retropatellar recess or bursa is usually present. An anterior recess release should be performed by use of electrocautery. The wall of scar should be released just proximal and anterior to the anterior horns of the medial and lateral meniscus. The release should be carried out distally 1 cm below the articular surface of the tibial plateau. Occasionally, a distinct pseudopatellar tendon will form between the inferior pole of the patella and anterior tibia. Resection of this dense band of tissue may be necessary. Care should be taken to avoid overzealous resection in this area. If the tendon is exposed to bone, then recurrence is likely. If retropatellar tendon fibrosis is present, but not patella infera, the use of a barrier to prevent adhesions of the patellar tendon to the anterior tibia may be needed. A nonreactive barrier such as the Bard hernia patch is an excellent choice. It can be cut to the approximate size and sutured to the anterior tibia directly posterior to the patellar tendon. The polyethylene surface faces the tendon. The patch may be left in place and does not require removal (Fig. 4-8). Care should also be taken to avoid abrading or severely cauterizing the bone, because this will increase the chances of recurrence.

Manipulation

Manipulation of the knee may be carried out at the time of arthroscopy or as a stand-alone procedure. After the selected anesthetic is administered, the knee is examined and gently manipulated. We recommend hand placement closed to the knee joint to obtain short lever arms and decrease the risk of fracture. We apply a slow steady pressure as the knee is manipulated. In most cases, you will feel and hear some tearing as the scar gives way. Manipulation for flexion only is generally successful. Closed manipulation for extension loss is rarely indicated and should be preceded by an arthroscopic release.

Open Release

We place the incision in the midline or slightly medially, depending on the previous surgical incision sites. A medial parapatellar arthrotomy is then used. Similar to arthroscopic débridement, a systematic approach should be used. The medial gutter and suprapatellar pouch are released from any adhesions. A lateral retinacular release is then performed. The intracondylar notch is evaluated and any pathology addressed. Osteophytes or cyclops lesions may be present. If the ACL has been reconstructed, position and isometry are evaluated. Débridement of the ACL is sometimes necessary in severe cases. Any heterotopic ossification or soft tissue calcifications encountered during this procedure are excised. The fat pad is then released from any adhesion. The fat pad must never be excised completely or recurrence is almost guaranteed. The retropatellar recess is then reestablished. If moderate to severe infrapatellar entrapment or bone to tendon contact in this area is present, we place an interposition polyethylene barrier in the retropatellar recess (see Fig. 4-7). This barrier will prevent recurrence of the adhesion between the anterior tibia and inferior patellar tendon. If significant patella infera is present (>1 cm), we perform a DeLee osteotomy, in which the tibial tubercle is moved anteriorly and superiorly. One or two screws are then placed to secure the tubercle back to the anterior tibia.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

CONCLUSIONS

Arthrofibrosis is a common but difficult condition to treat. The key to treating this problem successfully is to identify the cause. Knee ROM can be successfully restored with a directed approach. Surgical treatment for knee stiffness should not be initiated until the acute inflammatory process has resolved, with absence of warmth and swelling. Arthroscopic release with or without manipulation is successful in treating many areas of fibrosis within the knee. However, open release may be required for more severe cases with infrapatellar entrapment. Aggressive, painful postoperative therapy must be avoided. Using the principles described in this chapter, the reader should have a better understanding of how to manage the complicated stiff knee patient.

1. Freeman MA, Pinskerova V. The movement of the normal tibio-femoral joint. J Biomech. 2005;38:197-208.

2. Laubenthal KN, Smidt GL, Kettelkamp DB. A quantitative analysis of knee motion during activites of daily living. Phys Ther. 1972;52:34-43.

3. Enneking WF, Horowitz M. The intra-articular effects of immobilization on the human knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;54A:973-985.

4. Yaru NC, Daniel DM, Penner D. The effect of tibial attachment site on graft impingement in an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:217-220.

5. Markolf KL, Hame S, Hunter DM, et al. Effects of femoral tunnel placement on knee laxity and forces in an anterior cruciate ligament graft. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1016-1024.

6. Shelbourne KD, Wilckens JH, Mollabashy A, DeCarlo M. Arthrofibrosis in acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: the effect of timing of reconstruction and rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:332-336.

7. Harner CD, Irrgang JJ, Paul J, et al. Loss of motion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:499-506.

8. Bach BRJr, Jones GT, Sweet FA, Hager CA. Arthroscopy-assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon substitution: two- to four-year follow-up results. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:758-767.

9. Skutek M, Elsner HA, Slateva K, et al. Screening for arthrofibrosis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: analysis of association with human leukocyte antigen. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:469-473.

10. Cosgarea AJ, DeHaven KE, Lovelock JE. The surgical treatment of arthrofibrosis of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:184-191.

11. Kim DH, Gill TJ, Millett PJ. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthrofibrotic knee. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:187-194.

12. Millett PJ, Steadman JR. The role of capsular distention in the arthroscopic management of arthrofibrosis of the knee: A technical consideration. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:E31.