CHAPTER 8 The Stiff Elbow: Degenerative Joint Disease

Degenerative arthritis of the elbow remains uncommon, but when symptomatic, it can cause substantial disability.1–4 Post-traumatic arthritis and osteoarthritis of the elbow have been treated with nonoperative means or open procedures. However, arthroscopic series have documented outcomes similar to those of open procedures and with acceptable complication rates.5–9

ANATOMY

Pathologic processes include the loss of cartilage and fragmentation with reactive bone formation in the form of osteophytes and loose bodies, which contribute to impingement and joint contracture as the capsule becomes abnormally thickened and fibrotic.3,11 Bony osteophytes commonly occur on the tip of the olecranon and coronoid process. Significant osteophytes also can occur along the medial aspect of the coronoid and may not be obvious on standard plain radiographs. Similarly, osteophytes may be found at the radial head fossa and the posterior aspect of the capitellum. The osteophytes in this area are difficult to visualize at time of surgery but can be seen while viewing from the posterolateral gutter when performing the posterior portion of the procedure, and they can be removed through a working portal at the soft spot. These bony spurs contribute to the loss of extension, and osteophytes at the radial head fossa contribute to a lack of flexion by impingement.

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is uncommon, but when it occurs, it tends to manifest in manual laborers, athletes, or crutch and wheelchair ambulators.1–4,10 Post-traumatic stiffness and arthrosis can be problematic after fractures or dislocations of the elbow.

Symptoms include loss of motion, mechanical catching and locking, and pain.4,10 Pain often is felt at the end arc of motion, and it is more likely to be improved by arthroscopic means than pain experienced throughout the arc of motion, which typically indicates severe joint changes.

Patients frequently have signs and symptoms of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow, and they should be examined for and queried about dysesthesias or paresthesias and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution.4,12 Electrical studies can document the severity of cubital tunnel compression, but they may not be necessary. Nerve compression occurs after progressive contracture of the elbow and scarring at the cubital tunnel. Postoperatively, if a large restoration of motion is achieved but the ulnar nerve is not addressed, symptomatic ulnar neuritis or neuropathy can occur as the nerve is stretched further.

Diagnostic Imaging

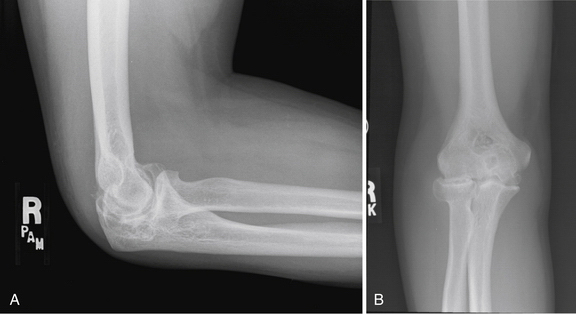

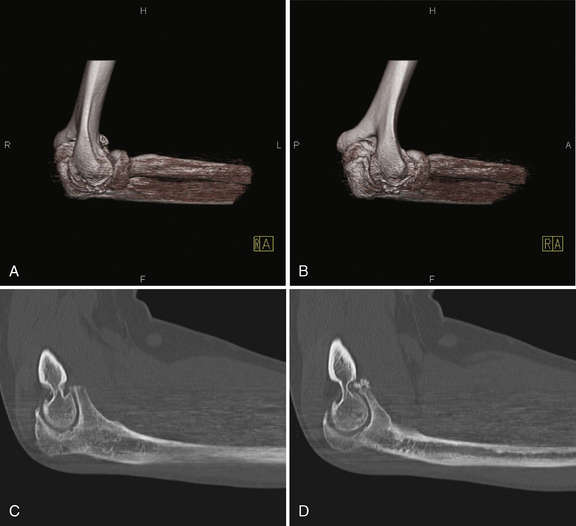

Plain radiographs should be obtained, and they typically demonstrate hypertrophic bony spurs and loose bodies (Fig. 8-1). The bone usually is sclerotic rather than osteopenic, as seen in rheumatoid arthritis. Computed tomography (CT) is useful, particularly with three-dimensional reconstructions, to map areas of interest that will require recontouring (Fig. 8-2). Using three-dimensional CT as a preoperative planning tool allows the surgeon to gain an increased appreciation of the osteophytic areas that require attention to improve range of motion. During the procedure, these areas may be overlooked without this three-dimensional map of normal and abnormal anatomy.

TREATMENT

Conservative Management and Alternatives to Arthroscopy

Nonoperative treatment options such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, corticosteroid injections, and activity modifications should be exhausted before considering surgery.13

Alternatives to arthroscopic procedures include open procedures such as resection arthroplasty of the ulnohumeral joint and open débridement such as the Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure. The medial “over-the-top” contracture release and the lateral column procedures allow access to the joint for excision of the thickened and abnormal capsule, with débridement of bony osteophytes.14,15 Total elbow arthroplasty reliably relieves pain and motion, but early aseptic loosening is an unsolved problem, especially in young and active patients. Joint fusion can relieve pain, but it has dramatic implications on function and is sometimes difficult to achieve.7

Arthroscopic Technique

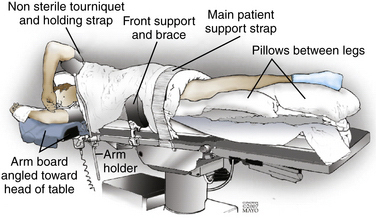

The arthroscopic technique and setup have been described previously.1,19,20 General endotracheal anesthesia is induced, and the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. Various positions have been described for elbow arthroscopy, but we prefer the lateral decubitus position as described here.

A conforming bean bag is useful to position and secure the patient. The operative arm is secured in a dedicated arm holder with the elbow higher than the shoulder and the forearm hanging freely. This allows unrestricted access to the elbow. A nonsterile tourniquet may be applied, or a sterile one is used after the arm is prepared and draped in the usual fashion (Fig. 8-3).

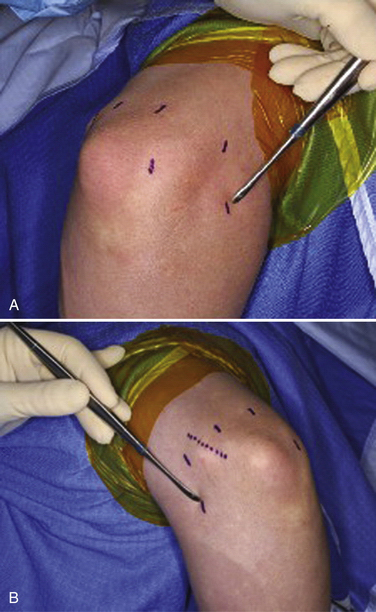

Before insufflation, portal sites and landmarks should be marked, because after the operation proceeds, bony landmarks may become difficult to palpate because of soft tissue fluid extravasation. The radial head, medial and lateral epicondyles, capitellum, and olecranon are marked, as is the location of the ulnar nerve (Fig. 8-4).

Anterior Portals

The proximal anterolateral and proximal anteromedial portals typically are used first and are considered safer than the distal anterolateral and anteromedial portals. The anterolateral (see Fig. 8-4A) portal is established first, with care taken to avoid and protect the radial nerve. This portal is established just anterior and distal to the radiocapitellar joint.

The anteromedial portal (see Fig. 8-4B) can be established using an inside-out technique with direct visualization from the anterolateral portal. The arthroscope is withdrawn from the anterolateral portal while the canula is kept in place. The blunt trocar is replaced in the canula and then pushed directly across the joint until it tents the skin overlying the medial side of the elbow. The skin is then incised over this region, and the trocar is pushed through the remaining soft tissue. A cannula may be placed over the trocar on the medial side, and the trocar is pulled back into the joint and out the lateral side.

Anterior Capsulectomy and Débridement

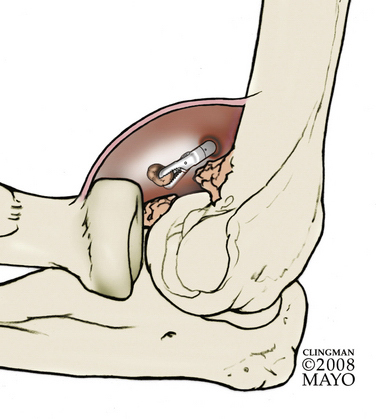

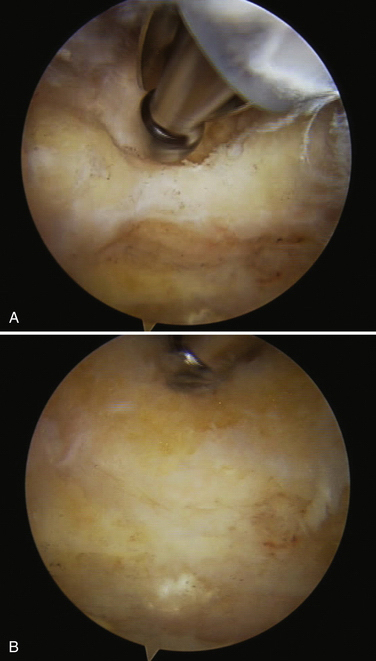

A 4.8-mm arthroscopic shaver is introduced through the anteromedial portal. Retraction through a proximal anterolateral portal is useful as arthroscopy proceeds. The shaver is used initially to débride soft tissue and to improve visualization. Loose bodies may be removed as they are visualized (Fig. 8-5) with arthroscopic graspers or a narrow jaw needle driver through an enlarged portal. Alternatively, large loose bodies may be burred down to a size small enough to be extracted.

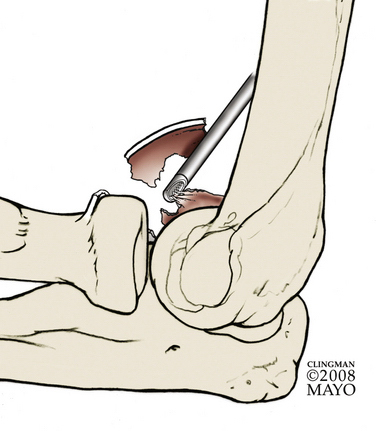

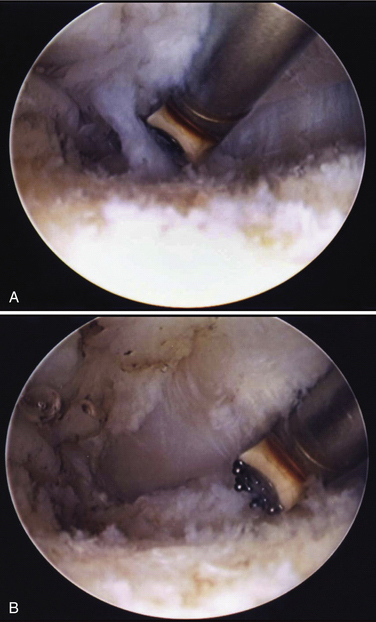

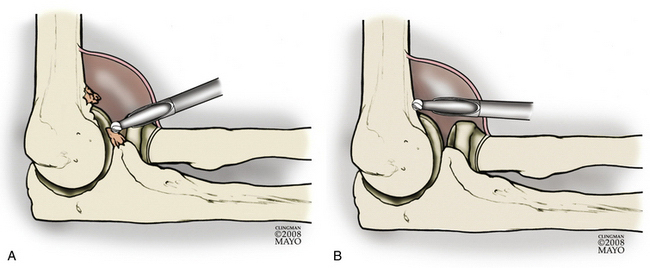

After visualization is adequate, bony work can proceed. A burr can be used to recontour the joint and remove osteophytes from the coronoid and radial head fossae (Fig. 8-6). Bony work should be near complete before addressing soft tissue contracture with capsular release, because after the capsulotomy is performed, fluid extravasation limits the duration of arthroscopy that may be safely performed.

FIGURE 8-6 Osteophytes are removed from the radial head and coronoid tip (A) and the anterior humerus (B).

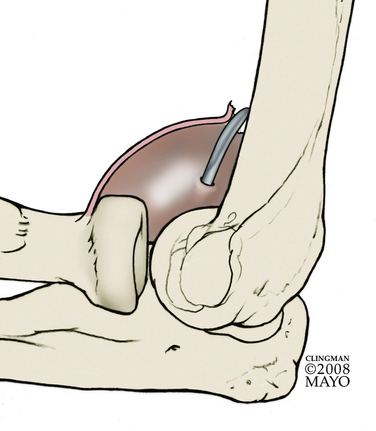

For capsular release, the anteromedial capsule is first stripped off the humerus with an elevator (Fig. 8-7). Large Steinmann pins or Howarth elevators may be used for retraction.

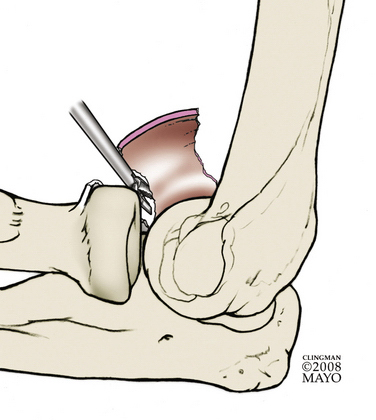

The arthroscope is placed in the lateral portal, and an arthroscopic biter is used on the anterior capsule, working from medial to lateral aspects (Fig. 8-8). The appearance of the fat stripe anterior to the radial head marks the safe limit of resection. The shaver is then introduced to completely resect the anterior capsule (Fig. 8-9). The arthroscope is then placed in the medial portal site, and working from the lateral side, the capsulectomy and bony débridement are completed.

Radial head excision is not needed in many patients with primary osteoarthritis of the elbow, because they often have preservation of much of the cartilage on the capitellum and radial head. In patients with complete loss of cartilage at the radiocapitellar articulation, significant crepitus, or loss of pronosupination, radial head excision may be beneficial. Many of these patients also have osteophytes on the posterior aspect of the capitellum and the radial head fossa, which should be resected. Occasionally, significant osteophytes limit pronosupination. They can be resected with a burr without excising the radial head itself. Radial head excision may be performed while viewing from the medial side. The anterolateral portal provides a good working portal for resection of the anterior aspect of the radial head with a burr and shaver. With progressive supination and pronation, resection of a large portion of the radial head can be achieved. Complete resection may be facilitated while viewing posterolaterally and bringing in the burr through the soft spot portal as a working portal. A detailed description of this procedure is provided in Chapter 11.

Posterior Capsular Débridement

After a posterolateral viewing portal and a direct posterior working portal are created, the shaver is placed in the direct posterior portal, and the view is improved by débridement of soft tissue. This is a potential space, and débridement is required to create a view. Subsequently, osteophytes are removed from the tip and sides of the olecranon and from the rim of the olecranon fossa (Fig. 8-10).

Patients who lack flexion preoperatively should also undergo posterolateral and posteromedial capsular releases. When addressing the posteromedial capsule, care should be exercised to identify and protect the ulnar nerve (Fig. 8-11).

Management of the Ulnar Nerve

If a large restoration of motion is anticipated after the procedure, if preoperative ulnar nerve symptoms exist, or if preoperative flexion measures less than 90 degrees, ulnar nerve decompression or transposition should be considered. This may be done with arthroscopic decompression (see Fig. 8-11) if the surgeon possesses the requisite skill or with an open subcutaneous transposition or in situ decompression.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation

After completion of the procedure, motion is assessed in the operating room to ensure adequate release. Portals are closed in the standard fashion with 3-0 nylon or Prolene sutures, and a sterile compressive dressing is applied. A posterior slab of plaster is used to splint the operative extremity in full extension, and the arm is elevated in the Statue of Liberty position overnight.

Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis, consisting of 75 mg of indomethacin three times daily for 6 weeks, is initiated. In selected patients who have had documented significant heterotopic ossification after an elbow procedure, radiation therapy is an option. A single dose of 700 cGy can be initiated within 72 hours of the procedure. We have found that this is rarely indicated for patients undergoing arthroscopic débridement of an arthritic elbow.

1. Stanley D. Prevalence and etiology of symptomatic elbow osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:386-389.

2. Redden JF, Stanley D. Arthroscopic fenestration of the olecranon fossa in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:14-16.

3. Tsuge K, Mizuseki T. Debridement arthroplasty for advanced primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Results of a new technique used for 29 elbows. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:641-646.

4. Antuna SA, Morrey BF, Adams RA, O’Driscoll SW. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: long-term outcome and complications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84A:2168-2173.

5. Adams JE, Wolff LH 3rd, Merten SM, Steinmann SP. Osteoarthritis of the elbow: results of arthroscopic osteophyte resection and capsulectomy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:126-131.

6. Ball CM, Meunier M, Galatz LM, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of post-traumatic elbow contracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:624-629.

7. Clasper JC, Carr AJ. Arthroscopy of the elbow for loose bodies. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:34-36.

8. Cohen AP, Redden JF, Stanley D. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow: a comparison of open and arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:701-706.

9. O’Driscoll SW. Arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26:691-706.

10. Morrey BF. Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Treatment by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:409-413.

11. Suvarna SK, Stanley D. The histologic changes of the olecranon fossa membrane in primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:555-557.

12. Oka Y, Ohta K, Saitoh I. Debridement arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;351:127-134.

13. Savoie FH 3rd, Nunley PD, Field LD. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, technique, and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214-219.

14. Tan V, Daluiski A, Simic P, Hotchkiss RN. Outcome of open release for post-traumatic elbow stiffness. J Trauma. 2006;61:673-678.

15. Mansat P, Morrey BF. The column procedure: a limited lateral approach for extrinsic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1603-1615.

16. Sarris I, Riano FA, Goebel F, et al. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty: results in primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;420:190-193.

17. Phillips NJ, Ali A, Stanley D. Treatment of primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:347-350.

18. Allen DM, Devries JP, Nunley JA. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty. Iowa Orthop J. 2004;24:49-52.

19. Vingerhoeds B, Degreef I, De Smet L. Debridement arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow (Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure). Acta Orthop Belg. 2004;70:306-310.

20. Kashigawi D, ed. Osteoarthritis of the Elbow Joint. Amersterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1986. 177-188

21. Wada T, Isogai S, Ishii S, Yamashita T. Debridement arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86A:233-241.

22. O’Driscoll SW. Operative treatment of elbow arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1995;7:103-106.

23. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Gordon R, MacKay M. Arthroscopic treatment for posterior impingement in degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:437-443.

24. Steinmann SP, King GJ, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2114-2121.

25. Gramstad GD, Galatz LM. Management of elbow osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:421-430.

26. Steinmann SP, King GJ, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:109-117.