CHAPTER 7 The Stiff Elbow: Arthrofibrosis

The elbow is particularly prone to stiffness following trauma. This propensity has been attributed to several factors, including the congruous nature of the joint, the presence of three articulations within a synovium-lined cavity, and the close relationship of the joint capsule to the intracapsular ligaments and surrounding muscles.1 Because of these factors, post-traumatic loss of motion is the most common complication after injury to the elbow joint. Arthroscopic techniques can improve motion and function in selected cases that fail conservative measures.

ANATOMY

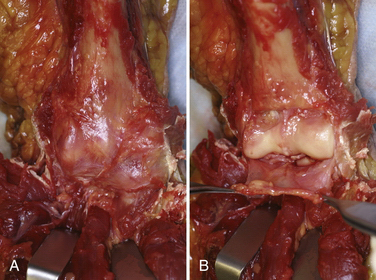

The capsule of the elbow is normally thin and transparent and has a high degree of elasticity (Fig. 7-1). However, after even relatively minor trauma, the capsule can undergo structural and biochemical alterations, leading to thickening, decreased compliance, and loss of motion.2 Prolonged immobilization after trauma may be a separate risk factor for the development of stiffness. In addition to capsular changes, the concavities of the humerus above the trochlea—the olecranon and coronoid fossae—can become filled with scar and fibrous tissue after injury. These fossae must be clear to accept the coronoid and olecranon processes at terminal elbow flexion and extension, respectively. In long-standing cases, secondary contracture of the brachialis and triceps muscles can limit motion.

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Patients with post-traumatic stiffness typically present with limitation of motion. Important aspects of the history include the mechanism of trauma, the initial treatment, and whether they have plateaued in their motion during rehabilitation. Loss of elbow extension is more common than loss of flexion. The examination must include observation of the upper extremity, looking specifically for deformity, swelling, atrophy, and other diagnostic characteristics.

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

Relative contraindications to arthroscopic elbow release include severe elbow contractures with minimal joint motion, prior ulnar nerve transposition surgery, and the presence of significant heterotopic bone. Surgical release of a contracted elbow is also contraindicated if a patient is deemed unable or unwilling to comply with the extensive program of postoperative therapy. Operative results depend on participation in a structured rehabilitation program. This is especially true for adolescents, who may not be dedicated to improving their elbow motion. If the ulnohumeral joint is incongruous, a simple release of the joint may not lead to improved motion and may worsen pain. Although pain at the extremes is common, patients who are candidates for elbow release surgery typically are pain free within their allowable arc of motion. If advanced post-traumatic arthritis exists in the ulnohumeral articulation, salvage-type procedures are required if surgery is undertaken.3

Conservative Management

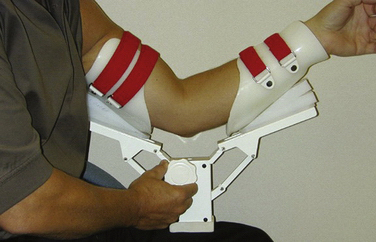

Patients who are candidates for elbow release surgery should undergo a course of structured rehabilitation. This ensures compliance and helps document that they have reached a plateau in their motion and function. In the past, dynamic splints that apply a constant tension to the soft tissues over long periods (e.g., 23 hours per day) were popular. However, patient-adjusted static braces are more effective for the elbow (Fig. 7-2). These braces use the principle of passive progressive stretch, allowing for stress relaxation of the soft tissues. They are applied for much shorter periods and are better tolerated by patients. Only when conservative measures fail and there remains a significant loss of mobility is surgical intervention considered.

Arthroscopic Technique

Specialized instruments can be helpful, such as cannulas that do not have any holes near the tip (Fig. 7-3). Because the elbow is smaller than, for example, the knee, and has less intra-articular space, standard cannulas can lead to fluid inadvertently entering the soft tissues while visualizing the joint.

In very experienced hands, the procedure appears equivalent to more traditional open methods. However, there is clearly a learning curve, and potential complications must be appreciated. They include nerve injury, excessive fluid extravasation, and iatrogenic chondral damage.4–9 If there is a question regarding visualization or safely, the surgeon must be prepared to convert the procedure to an open approach.10–13

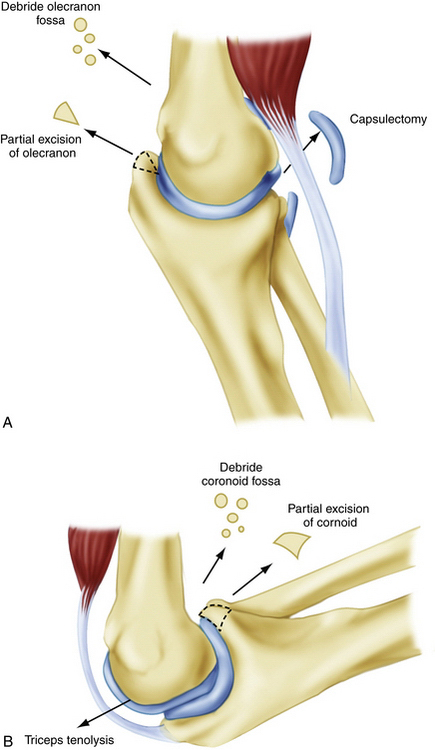

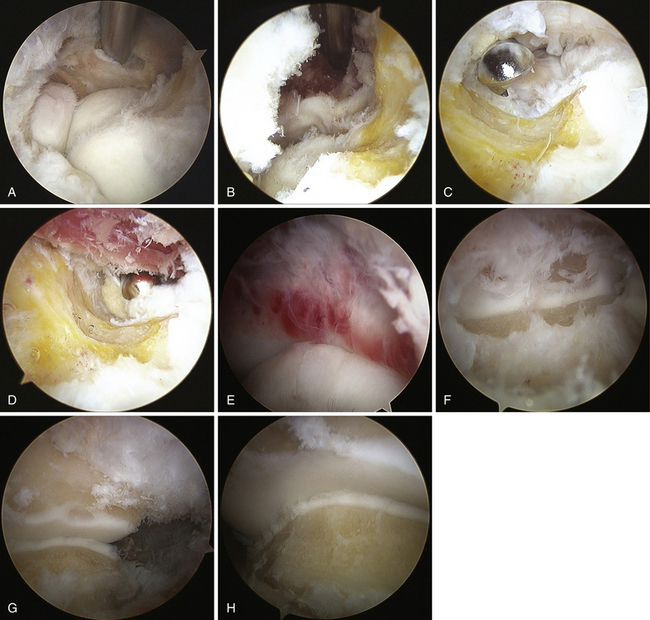

From a purely mechanical standpoint, to improve elbow extension, posterior impingement must be removed between the olecranon tip and the olecranon fossa. Anteriorly, tethering soft tissues, such as the anterior joint capsule and any adhesions between the brachialis and the humerus, must be released (Fig. 7-4). Similarly, to improve elbow flexion, the surgeon must release any soft tissue structures posteriorly that may be tethering the joint. They include the posterior joint capsule and the triceps muscle, which can become adherent to the humerus. The surgeon must remove any bony or soft tissue impingement anteriorly, including any soft tissue overgrowth in the coronoid and radial fossae (see Fig. 7-4). There must be a concavity above the humeral trochlea and capitellum to accept the coronoid centrally and the radial head laterally for full flexion to occur.

Elbow release surgery is typically performed under regional anesthesia with a long-acting block that allows postoperative muscular relaxation and pain control. An indwelling axillary catheter also can be effective. We prefer the prone position for elbow arthroscopy. The lateral decubitus position may also be used. It is facilitated by arthroscopic arm-holding devices (Fig. 7-5). The prone position is more complicated from an anesthesia perspective, but it does completely free the shoulder and makes conversion to an open approach easier if required.

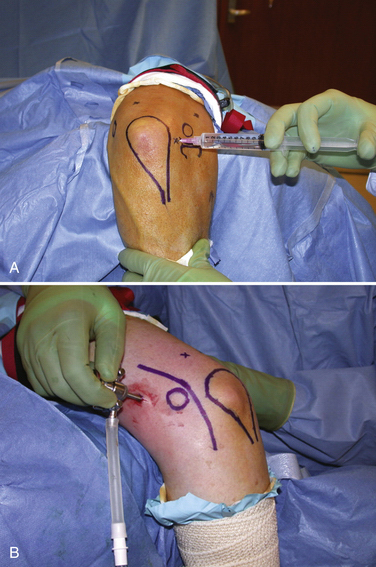

The elbow is insufflated with saline introduced through the soft spot (direct midlateral) portal (Fig. 7-6). The anteromedial portal is established by placing a blunt trocar or switching stick along the anterior humerus, aiming toward the radial head laterally. This is started several centimeters proximal and anterior to the medial epicondyle (see Fig. 7-6). In cases of post-traumatic stiffness with a contracted capsule, it can be difficult to enter the joint. Care must be taken to hug the anterior humeral cortex because the capsule can be quite adherent, pushing the instrument into an extra-articular plane. Beneath the capsule and in the joint, the trocar or switching stick can be used to lever anteriorly to help strip the capsule and develop a space in which to work. The anterolateral portal is established using an inside-out technique. It is most effectively placed just anterior to the radiocapitellar articulation (Fig. 7-7).

The anterior joint is cleared of any synovitis or adhesions that are present. Mechanical instruments are typically used, although thermal devices can be quite effective at removing soft tissue. Care is taken to temporarily increase the inflow while using a thermal device to decrease heat generation within the joint. The coronoid fossa is cleared and deepened, removing any fibrous tissue down to the bony floor. This is also true of the radial fossa just above the capitellum. The radial fossa must be free to accept the radial head during elbow flexion. The arthroscope and the working instruments must be switched rapidly and effectively from medial to lateral positions during this work (see Fig. 7-7).

After the fossae are cleared and any necessary bony work is completed, the anterior capsule is addressed. It is first well defined and then partially or completely resected. The radial (posterior interosseous) nerve lives just anterior to the joint capsule and near the midline of the radiocapitellar joint. Removing the capsule proximal to the trochlea is much safer than distal excision. Any capsule work done at the level of the joint line must be done with great care. Retractors can be helpful to aid visualization. They can obviate the need for increased fluid pressure to distend the joint for visualization and are helpful for fluid management. After part of the capsule is released, fluid distention is less effective, and fluid extravasation into the periarticular soft tissues more readily occurs. This must be limited, because it is much more difficult to work within the elbow after a significant amount of fluid has extravasated. The capsule must be released all the way out to the supracondylar ridges to achieve a complete release (see Fig. 7-7).

After the anterior joint work is completed, attention is focused posteriorly. We typically leave a cannula in the anterior joint while working in the back. This helps to maintain outflow during the procedure. With the elbow extended maximally to protect the posterior trochlea, a blunt elevator is used to blindly strip and clear the olecranon fossa and elevate the posterior joint capsule. Identification of the concavity of the fossa should be possible using tactile feedback. The arthroscope is introduced into the posterior or the posterolateral portal. The latter is started approximately 1 cm proximal to the midpoint between a line drawn from the olecranon tip to the lateral epicondyle. The posterior portal is established 3 to 4 cm above the olecranon tip in the midline. The camera is then turned to look in a distal direction. In cases of post-traumatic stiffness, soft tissue often must be débrided in the olecranon fossa to allow for full visualization of the articular surfaces (see Fig. 7-7). Proximal retractors are also very helpful in the posterior joint. The posterior capsule is freed from the humerus proximally, and it can be partially resected. Typically, this capsule is less hypertrophic than the anterior capsule. Establishing a soft spot portal (direct midlateral) may facilitate visualization and help to free the posterolateral gutter. Any soft tissue or bony overgrowth at the tip of the olecranon is removed, including the medial and lateral corners (see Fig. 7-7).

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Several rehabilitation programs may be effective after elbow release surgery. We typically use continuous passive motion that is begun immediately in the recovery room (Fig. 7-8). It is used the next morning to help maintain the motion gained at surgery. Formal therapy is commonly begun on postoperative day 1. The dressing is removed, and edema-control modalities (e.g., edema sleeve, Ace wrap) are used to limit swelling. Active and gentle passive elbow motion is combined with intermittent continuous passive motion. Static progressive elbow bracing is begun early in the postoperative period. Flexion and extension are alternated based on the preoperative deficit and the early progress of the elbow.

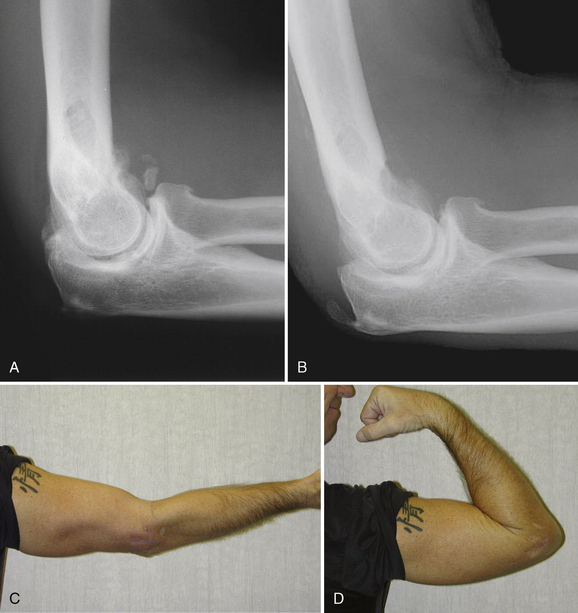

A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent (e.g., Indocin) is commonly prescribed as a prophylaxis against heterotopic ossification for several weeks postoperatively. This also helps to limit inflammation of the joint and soft tissues during rehabilitation. The physician must follow these patients closely. Although most ultimate elbow motion is gained during the first 6 to 8 weeks, patients can continue to make gains in terminal flexion and extension for several months postoperatively. With proper patient selection, results can be gratifying, with predictable recovery of a functional arc of elbow motion and pain relief (Fig. 7-9).14–18

FIGURE 7-9 Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) lateral radiographs were obtained for the patient depicted in Figure 7-7. He developed a post-traumatic elbow contracture, with preoperative motion measuring approximately 45 to 105 degrees. Notice the deepening of the anterior fossa above the trochlea and capitellum and removal of the posterior olecranon spur. Clinical photographs taken 1 week after arthroscopic elbow release show early improvement in elbow extension (C) and flexion (D).

CONCLUSIONS

Arthroscopic release of the stiff elbow requires a high degree of surgical skill and knowledge of the bony and soft tissue anatomy of the elbow. In properly selected patient, this procedure can have gratifying results that are similar to those of traditional open procedures. Care must be taken to ensure proper visualization, management of fluid extravasation, and protection of important neurovascular structures. If any doubt exists, the surgeon must be prepared to convert to an open procedure.

1. Modabber MR, Jupiter JB. Current concepts review: reconstruction for post-traumatic conditions of the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77A:1431-1446.

2. Cohen MS, Schimel DR, Masuda K, et al. Structural and biochemical evaluation of the elbow capsule following trauma. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:484-490.

3. Jupiter JB, O’Driscoll SW, Cohen MS. The assessment and management of the stiff elbow. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:93-112.

4. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:784-787.

5. Kelberine F, Landreau P, Cazal J. Arthroscopic management of the stiff elbow. Chir Main. 2006;25(suppl 1):S108-S113.

6. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83A:25-34.

7. Lynch GJ, Meyers JF, Whipple TL, Caspari RB. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: inherent risks. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:190-197.

8. Park JY, Cho CH, Choi JH, et al. Radial nerve palsy after arthroscopic anterior capsular release for degenerative elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1360.e1-1360.e3.

9. Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Anterior interosseus injury following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:756-758.

10. Cohen MS. Open capsular release for soft-tissue contracture of the elbow. In: Yamaguchi K, King GJW, McKee MD, O’Driscoll SW, eds. Advanced Reconstruction: Elbow. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2007:195-204.

11. Cohen MS, Hastings H. Capsular release for contracture of the elbow: operative technique and functional results. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:133-139.

12. Cohen MS, Hastings H. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: operative release using a lateral collateral sparing approach. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80B:805-812.

13. Mansat P, Morrey BF. The column procedure: a limited lateral approach for extrinsic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80A:1603-1615.

14. Ball CM, Meunier M, Galatz LM, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of post-traumatic elbow contracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:624-629.

15. Kelly EW, Bryce R, Coghlan J, Bell W. Arthroscopic debridement without radial head excision of the osteoarthritis elbow. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:151-156.

16. Nguyen D, Proper SI, MacDermid JC, et al. Functional outcomes of arthroscopic capsular release of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:842-849.

17. Salini V, Palmieri D, Colucci C, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of post-traumatic elbow stiffness. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2006;46:99-103.

18. Savoie FH, Nunley PD, Field LD, Savoie FH. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, technique, and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214-219.