The spleen

Introduction

The history of the spleen, including surgery, anatomy and physiology, has been nicely detailed by McClusky et al. and will not be reviewed here.1,2 The spleen lies in the posterior left upper quadrant superior to the level of the costal margin. It is attached to adjacent structures via a series of ligaments including the splenophrenic, splenorenal, splenocolic and gastrosplenic ligaments.

Postsplenectomy sepsis

Asplenic patients are at increased risk of developing overwhelming sepsis throughout their lives. This lifetime risk of postsplenectomy sepsis is approximately 0.02% for adults.3 In a recent large population-based study from Scotland, Kyaw et al.4 showed severe infection, defined as need for hospitalisation, occurred with an incidence of 7 per 100 person-years. The risk of overwhelming infection, defined as septicaemia or meningitis, was 0.89 per 100 person-years.

Trauma

The most common cause of splenic injury is blunt trauma.10 Rupture may also occur from penetrating trauma, iatrogenic injury or, rarely, diseases such as mononucleosis or typhoid. Management of splenic trauma has evolved significantly over the last several years. Non-operative management is used in 60–80% of blunt injury cases, with success rates of 95%.11 Initial management of all traumas should begin with primary and secondary surveys completed according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines.12 Diagnostic evaluation for splenic injury follows and is based on the haemodynamic status of the patient. Haemodynamically unstable patients should undergo rapid focused assessment by sonography for trauma (FAST).11,13 If FAST is not available or inconclusive, diagnostic peritoneal lavage may be used. Scant fluid on the FAST exam should prompt a search for other causes of shock. A large amount of intraperitoneal blood on FAST is an indication for emergent laparotomy. Currently, exploration for traumatic splenic injury is performed in an open fashion.

Haemodynamically stable patients with physical findings of abdominal trauma should undergo abdominal computed tomography (CT) to assess all potential injuries. A grading system for splenic injury based on CT findings has been developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST)14 and is presented in Table 9.1. The decision to proceed to operative exploration, however, is not based solely upon these grades. All grades of injury have undergone successful non-operative management. Patients with higher grade injuries or age > 55 years, however, are at increased risk for failure of non-operative management and warrant a low threshold to proceed with operative intervention.15–17

Table 9.1

American Association for the Study of Trauma (AAST) splenic injury scale based on CT criteria

| Grade | Injury description | |

| I | Haematoma | Subcapsular, < 10% surface area |

| Laceration | Capsular tear, < 1 cm parenchymal depth | |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50% surface area. Intraparenchymal, < 5 cm in diameter |

| Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth, which does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular, > 50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal haematoma; intraparenchymal haematoma ≥ 5 cm or expanding |

| Laceration | > 3 cm parenchymal depth, or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularisation (> 25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury that devascularises spleen |

Indications for operative intervention in splenic trauma from the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) Patient Care Guidelines18 are shown in Box 9.2. The group also suggests an aggressive non-operative approach for children < 14 years of age.

The use of selective arterial embolisation in the management of splenic trauma was initially described by Sclafani et al.19 but remains somewhat controversial. Protocol-driven strategies utilising both conservative and aggressive indications for implementing embolisation have yielded excellent results.20,21 Other groups, however, have highlighted difficulties in using CT grading systems and selective arterial embolisation, hence the conflict preventing widespread use.22,23

As many as 40% of splenectomies are performed as a result of iatrogenic splenic injury.24,25 Such injuries usually result from excess traction against either the splenic ligaments or adhesions to the spleen. The standard use of laparoscopic procedures may lower the risk of splenic injury by providing better visualisation, application of less traction, improved instrumentation for perisplenic dissection, and better control of capsular haemorrhage by the pressure of the pneumoperitoneum.26

Haemostatic control of splenic injuries begins with direct pressure. Haemostatic agents such as microfibrillar collagen, microporous polysaccharide hemispheres or injectable haemostatic matrices may be applied to aid haemostasis.27 Haemostatic instruments such as argon-beam coagulators may also be helpful. Ligation of selected arteries in the hilum may help control bleeding but potentially lead to a need for partial splenectomy. Splenorrhaphy and partial splenectomy have been described for splenic trauma; however, Holubar et al.28 showed the most important factor in preventing adverse outcome after iatrogenic splenic injury is prompt cessation of bleeding by whatever means. Splenectomy, while not desirable, is preferable to significant blood loss and should be performed when bleeding is excessive, if the patient cannot tolerate prolonged procedures, or if there are other factors that would make re-bleeding a greater risk than splenectomy.

Elective indications for splenectomy

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura

Approximately 80% of patients respond to splenectomy and 65–85% of patients sustain response long term.31 There is no widely accepted factor to predict response to splenectomy. If platelet counts drop after splenectomy, peripheral blood smears may show absence of nuclear inclusions (e.g. Howell–Jolley bodies) indicating residual splenic tissue. Nuclear medicine scans, magnetic resonance imaging or CT may help localise such remnants for re-exploration or embolisation. Mild to moderate degrees of thrombocytopenia without symptoms of purpura or bleeding postsplenectomy may be observed without resuming medical therapy.31

Evans syndrome

Evans syndrome is characterised by autoimmune haemolytic anaemia and autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Splenectomy may be curative in up to 40% of patients and improve the situation in up to 60%; however, failures are common.32

Hereditary spherocytosis

Hereditary spherocytosis results from abnormalities of membrane proteins, particularly spectrin. The degree of spectrin deficiency varies, as does the pattern of inheritance. Approximately 75% of cases demonstrate an autosomal dominant pattern. Autosomal recessive patients have a greater degree of spectrin deficiency and unlike the autosomal dominant patients do not respond to splenectomy. The disease is characterised by extravascular destruction of red cells, particularly in the spleen.33

Several groups have reported the use of subtotal splenectomy for the treatment of hereditary spherocytosis and demonstrated amelioration of anaemia and maintenance of immune function. Mild to moderate haemolysis, however, may persist and gallstone formation and aplastic crises still developed in some patients.35–37

Thallassaemias

Genetic abnormalities resulting in abnormal haemoglobin structure, such as thalassaemias, may require splenectomy. Defective alpha chains and beta chains in the haemoglobin tetramer lead to alpha thalassaemia and beta thalassaemia, respectively. The alpha chains precipitate in the absence of the beta chains and create the more severe beta thalassaemia. Blood transfusions and chelation therapy are the mainstays of treatment; however, stem cell transplantation is playing a greater role in the management of this disease.38 Splenectomy is rarely required. Thalassaemia patients are at increased risk of infective complications postoperatively.

Sickle cell anaemia

Sickle cell anaemia is characterised by high HgF levels. Major indications for splenectomy are recurrent acute splenic sequestration crisis, hypersplenism, splenic abscess and massive splenic infarction.39 Cholecystectomy is recommended if gallstones are present, also simplifying the diagnosis if abdominal crisis occurs in the future.

Volvulus

Some spleens have elongated or absent ligamentous attachments, leading to a ‘wandering’ spleen. These spleens may undergo torsion on their vascular pedicle. Patients present with severe abdominal pain and a right lower quadrant mass, occasionally occurring intermittently. A viable spleen should be returned to the left upper quadrant and fixed in place using a mesh sac tacked to the diaphragm.40 A necrotic spleen requires splenectomy.

Haemangiomas

Haemangiomas are the most common benign neoplasm in the spleen. Small lesions (less than 4 cm) may be safely watched.41 Risks presented by larger haemangiomas are unclear. Therefore, splenectomy versus observation must be individually determined.

Cysts

Cystic lesions of the spleen are often classified as parasitic or non-parasitic. Cyst size and symptoms determine surgical intervention. Asymptomatic cysts with reassuring radiographic features may be observed. Cysts greater than 5 cm in diameter are at potentially higher risk of rupture, so intervention may be indicated either by laparoscopic deroofing or resection. Percutaneous drainage and alcohol ablation have also been used with unreliable results. Bacterial abscesses may be drained either by percutaneous or surgical means. Occasionally, splenectomy is required.42

Parasitic cysts are usually echinococcal in origin and the diagnosis is often confirmed by serological studies. Splenic conserving techniques may be appropriate for early disease or disease located at the perimeter of the spleen.43 Spillage of hydatid cyst contents must be meticulously avoided as anaphylactic shock may occur.

Technique

Laparoscopic splenectomy

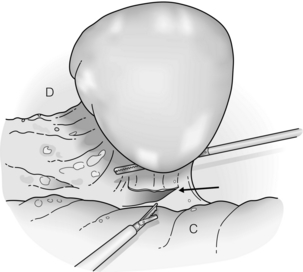

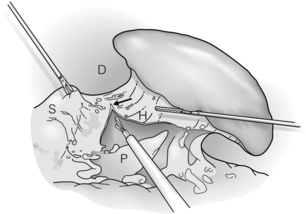

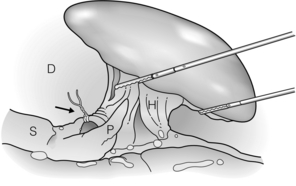

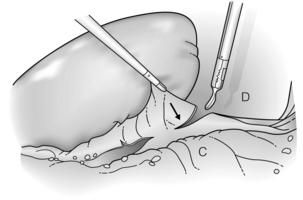

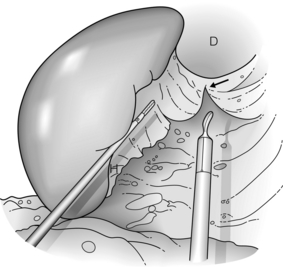

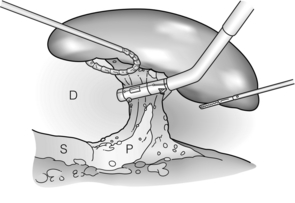

The operative goal of laparoscopic splenectomy is circumferential mobilisation of the splenic hilum for transection. Reported techniques vary in the sequence in which the ligaments are divided, but all procedures involve the same steps.46,47 The patient is placed in the right lateral semidecubitus position and is rolled back slightly from full lateral decubitus so that the midline is exposed should urgent conversion to open surgery be required. The surgeon and camera operator stand in front of the patient and one assistant stands behind the patient. We prefer a five-port technique but others report a four-port technique.47 The omentum and transverse mesocolon are examined for accessory spleens. A wary eye is kept to identify accessory spleens throughout the procedure. Steps of dissection are illustrated in Figs 9.1–9.6.46 Dissection begins by dividing the splenocolic ligament and then proceeds anteriorly. The lesser sac is opened and the gastrosplenic ligament, including the short gastric vessels, is divided. The main splenic artery is isolated and ligated, if feasible, to facilitate later hilar transaction and decrease bleeding at the staple line. The lateral attachments are divided. Some surgeons will leave the highest end of the splenophrenic ligament attached until after hilar transection to prevent rotation; this is known as the ‘hanged spleen’ technique.48

Figure 9.1 After exploration, dissection of the splenic attachments is begun with the splenocolic ligament (arrow). Traction is always placed toward the spleen with countertraction, if necessary. C, colon; D, diaphragm. Reprinted with permission from Schlinkert RT, Teotia SS. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:100–1. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Figure 9.2 The gastrosplenic ligament is divided (arrow). Dissection is begun at the inferior aspect and continued until all short gastric vessels are divided. The superior medial aspect of the splenophrenic ligament is also divided. D, diaphragm; H, hilum; P, pancreas; S, stomach. Reprinted with permission from Schlinkert RT, Teotia SS. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:100–1. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Figure 9.3 If the splenic artery can be identified superior to the tail of the pancreas, it is ligated (arrow). D, diaphragm; H, hilum; P, pancreas; S, stomach. Reprinted with permission from Schlinkert RT, Teotia SS. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:100–1. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Figure 9.4 The splenorenal ligament (arrow) is divided, retracting the spleen anteriorly. Areolar connective tissue between this ligament and the splenic hilum is gently divided. C, colon; D, diaphragm. Reprinted with permission from Schlinkert RT, Teotia SS. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:100–1. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Figure 9.5 The gastrophrenic ligament is divided (arrow) and areolar connective tissue again is dissected. At the completion of this step, the splenic hilum has been mobilised circumferentially. D, diaphragm; H, hilum. Reprinted with permission from Schlinkert RT, Teotia SS. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:100–1. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Figure 9.6 The splenic hilum is now divided with the spleen retracted far into the left upper quadrant. After transection, the spleen is placed in a bag, morcellated and removed. D, diaphragm; P, pancreas; S, stomach. Reprinted with permission from Schlinkert RT, Teotia SS. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:100–1. American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

References

1. McClusky, D.A., 3rd., Skandalakis, L.J., Colborn, G.L., et al, Tribute to a triad: history of splenic anatomy, physiology, and surgery – part 1. World J Surg 1999; 23:311–325. 9933705

2. McClusky, D.A., 3rd., Skandalakis, L.J., Colborn, G.L., et al, Tribute to a triad: history of splenic anatomy, physiology, and surgery – part 2. World J Surg 1999; 23:514–526. 10085403

3. Galvan, D.A., Peitzman, A.B., Failure of nonoperative management of abdominal solid organ injuries. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006; 12:590–594. 17077692

4. Kyaw, M.H., Holmes, E.M., Toolis, F., et al, Evaluation of severe infection and survival after splenectomy. Am J Med 2006; 119:276.e1–276.e7. 16490477

5. Davies, J.M., Barnes, R., Milligan, D., Update of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen. Clin Med 2002; 2:440–443. 12448592

6. Working Party of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology Clinical Haematology Task Force, Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen. Br Med J 1996; 312:430–434. 8601117 Evidence-based guidelines outlining prevention of sepsis in splenectomised patients.

7. Mourtzoukou, E.G., Pappas, G., Peppas, G., et al, Vaccination of asplenic or hyposplenic adults. Br J Surg 2008; 95:273–280. 18278784 Evidence-based guidelines outlining prevention of sepsis in splenectomised patients.

8. Shatz, D.V., Schinsky, M.F., Pais, L.B., et al, Immune responses of splenectomized trauma patients to the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at 1 versus 7 versus 14 days after splenectomy. J Trauma 1998; 44:760–766. 9603075

9. Kyaw, M.H., Holmes, E.M., Chalmers, J., et al, A survey of vaccine coverage and antibiotic prophylaxis in splenectomised patients in Scotland. J Clin Pathol 2002; 55:472–474. 12037033

10. Savage, S.A., Zarzaur, B.L., Magnotti, L.J., et al, The evolution of blunt splenic injury: resolution and progression. J Trauma 2008; 64:1085–1091. 18404079

11. Schroeppel, T.J., Croce, M.A., Diagnosis and management of blunt abdominal solid organ injury. Curr Opin Crit Care 2007; 13:399–404. 17599009

12. American College of Surgeons. Advanced trauma life support for doctors, 8th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

13. Rozycki, G.S., Surgeon-performed ultrasound: its use in clinical practice. Ann Surg 1998; 228:16–28. 9671062

14. Tinkoff, G., Esposito, T.J., Reed, J., et al, American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale I: spleen, liver, and kidney, validation based on National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg 2008; 207:646–655. 18954775

15. Harbrecht, B.G., Peitzman, A.B., Rivera, L., et al, Contribution of age and gender to outcome of blunt splenic injury in adults: multicenter study of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma 2001; 51:887–895. 11706335

16. McIntyre, L.K., Schiff, M., Jurkovich, G.J., Failure of nonoperative management of splenic injuries: causes and consequences. Arch Surg 2005; 140:563–569. 15967903

17. Smith, J.S., Jr., Wengrovitz, M.A., DeLong, B.S., Prospective validation of criteria, including age, for safe, nonsurgical management of the ruptured spleen. J Trauma 1992; 33:363–369. 1404503

18. Patient Care Committee of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT), Surgical treatment of injuries and diseases of the spleen. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9:453–454. 15906472

19. Sclafani, S.J., Shaftan, G.W., Scalea, T.M., et al, Nonoperative salvage of computed tomography-diagnosed splenic injuries: utilization of angiography for triage and embolization for hemostasis. J Trauma 1995; 39:818–827. 7473996

20. Cooney, R., Ku, J., Cherry, R., et al, Limitations of splenic angioembolization in treating blunt splenic injury. J Trauma 2005; 59:926–932. 16374283

21. Haan, J., Ilahi, O.N., Kramer, M., et al, Protocol-driven nonoperative management in patients with blunt splenic trauma and minimal associated injury decreases length of stay. J Trauma 2003; 55:317–322. 12913643

22. Barquist, E.S., Pizano, L.R., Feuer, W., et al, Inter- and intrarater reliability in computed axial tomographic grading of splenic injury: why so many grading scales? J Trauma 2004; 56:334–338. 14960976

23. Harbrecht, B.G., Ko, S.H., Watson, G.A., et al, Angiography for blunt splenic trauma does not improve the success rate of nonoperative management. J Trauma 2007; 63:44–49. 17622867

24. Cassar, K., Munro, A., Iatrogenic splenic injury. J R Coll Edinb 2002; 47:731–741. 12510965

25. Merchea, A., Dozois, E.J., Wang, J.K., et al, Anatomic mechanisms for splenic injury during colorectal surgery. Clin Anat. 2012;25(2):212–217. 21800366

26. Malek, M.M., Greenstein, A.J., Chin, E.H., et al, Comparison of iatrogenic splenectomy during open and laparoscopic colon resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2007; 17:385–387. 18049397

27. Chung, B.I., Desai, M.M., Gill, I.S., Management of intraoperative splenic injury during laparoscopic urological surgery. BJU Int 2011; 108:572–576. 21062394

28. Holubar, S.D., Wang, J.K., Wolff, B.G., et al, Splenic salvage after intraoperative splenic injury during colectomy. Arch Surg 2009; 144:1040–1045. 19917941

29. Ruggeri, M., Rodeghiero, F., Tosetto, A. Steroids and intravenous immune globulines for the treatment of acute idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2007. Evidence base for medical therapy of ITP.

30. Portielje, J.E., Westendorp, R.G., Kluin-Nelemans, H.C., et al, Morbidity and mortality in adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2001; 97:2549–2554. 11313240

31. Provan, D., Stasi, R., Newland, A.C., et al, International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2010; 115:168–186. 19846889 Evidence base for medical therapy of ITP.

32. Duperier, T., Felsher, J., Brody, F., Laparoscopic splenectomy for Evans syndrome. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2003; 13:45–47. 12598759

33. Smedley, J.C., Bellingham, A.J., Current problems in haematology. 2: Hereditary spherocytosis. J Clin Pathol 1991; 44:441–444. 2066420

34. Bolton-Maggs, P.H., Langer, J.C., Iolascon, A., et al, Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary spherocytosis – 2011 update. Br J Haematol 2011; 156:37–49. 22055020 Evidence base for medical therapy of hereditary spherocytosis.

35. Stoehr, G.A., Stauffer, U.G., Eber, S.W., Near-total splenectomy: a new technique for the management of hereditary spherocytosis. Ann Surg 2005; 241:40–47. 15621989

36. Bader-Meunier, B., Gauthier, F., Archambaud, F., et al, Long-term evaluation of the beneficial effect of subtotal splenectomy for management of hereditary spherocytosis. Blood 2001; 97:399–403. 11154215

37. Buesing, K.L., Tracy, E.T., Kiernan, C., et al, Partial splenectomy for hereditary spherocytosis: a multi-institutional review. J Pediatr Surg 2011; 46:178–183. 21238662

38. Locatelli, F., De Stefano, P., Innovative approaches to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with thalassaemia. Haematologica 2005; 90:1592–1594. 16330431

39. Al-Salem, A.H., Indications and complications of splenectomy for children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Surg 2006; 41:1909–1915. 17101369

40. Rescorla, F.J., West, K.W., Engum, S.A., et al, Laparoscopic splenic procedures in children: experience in 231 children. Ann Surg 2007; 246:683–688. 17893505

41. Willcox, T.M., Speer, R.W., Schlinkert, R.T., et al, Hemangioma of the spleen: presentation, diagnosis, and management. J Gastrointest Surg 2000; 4:611–613. 11307096

42. Hansen, M.B., Moller, A.C., Splenic cysts. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2004; 14:316–322. 15599294

43. Kalinova, K., Stefanova, P., Bosheva, M., Surgery in children with hydatid disease of the spleen. J Pediatr Surg 2006; 41:1264–1266. 16818060

44. Habermalz, B., Sauerland, S., Decker, G., et al, Laparoscopic splenectomy: the clinical practice guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc 2008; 22:821–848. 18293036

45. Park, A.E., Birgisson, G., Mastrangelo, M.J., et al, Laparoscopic splenectomy: outcomes and lessons learned from over 200 cases. Surgery 2000; 128:660–667. 11015100

46. Schlinkert, R.T., Teotia, S.S., Laparoscopic splenectomy. Arch Surg 1999; 134:99–103. 9927141

47. Katkhouda, N., Hurwitz, M.B., Rivera, R.T., et al, Laparoscopic splenectomy: outcome and efficacy in 103 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 1998; 228:568–578. 9790346

48. Delaitre, B., Laparoscopic splenectomy. The “hanged spleen” technique. Surg Endosc 1995; 9:528–529. 7676379