The spleen

Structure

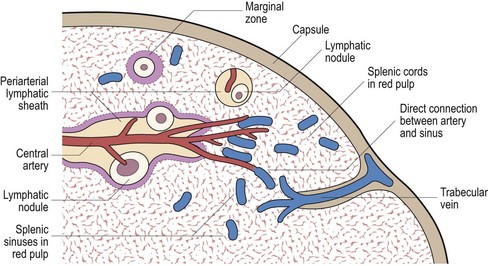

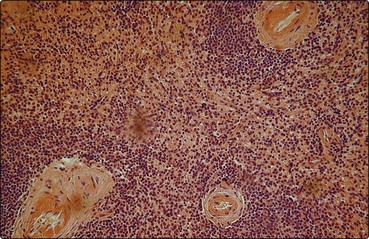

The splenic artery penetrates the thick capsule which invests the organ (Fig 5.1). Branches of the splenic artery are surrounded by a highly organised aggregate of lymphoid tissue which is termed the ‘white pulp’ (Fig 5.2). Intimate to the central arteriole is the ‘periarteriolar lymphatic sheath’ – an area mainly populated by T-lymphocytes. Among these T-lymphocytes are non-phagocytic, antigen-presenting cells known as ‘interdigitating cells’. Spaced at intervals in the periarteriolar lymphatic sheath are lymphoid follicles (‘Malpighian bodies’). In an inactive state these follicles are composed of recirculating B-lymphocytes intertwined with cytoplasmic processes of follicular dendritic cells. The latter cells may play a role in long-term antibody production. When contact with antigen stimulates B-cell activation, a germinal centre of rapidly dividing cells forms in the follicle. This is a key area in the normal B-lymphocyte proliferative response and development of B-cell memory (see p. 8 for discussion of lymphocytes).

Abnormal splenic states

Surgical removal of the spleen (splenectomy) may be indicated in a variety of haematological disorders and following trauma. The spleen may also be absent as a congenital anomaly, often associated with transpositions or malformations of the great vessels and viscera (‘asplenia syndrome’). Reduced splenic function can result from splenic atrophy in disorders such as sickle cell anaemia, adult coeliac disease and essential thrombocythaemia (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

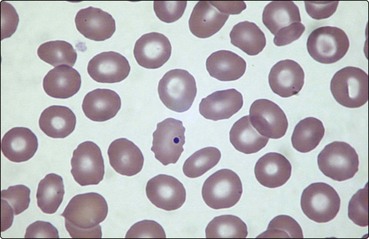

Hyposplenism leads to characteristic changes in the blood film (Fig 5.3). Changes in red cell appearance include the presence of Howell–Jolly bodies, Pappenheimer (siderotic) granules and target cells. Other less regular red cell features are lipid-rich acanthocytes and circulating nucleated cells. There is often a moderate rise in the lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet count. Approximately one-third of circulating platelets are pooled in the normal spleen. The increase in platelets post-splenectomy is frequently impressive (greater than 1000 × 109/L) but the count usually falls to a lower level in the longer term. Quantitation of splenic function is not straightforward. Methods include the measurement of the percentage of pitted erythrocytes using interference phase microscopy, various immunological parameters and scintigraphy.

Fig 5.3 The blood film in hyposplenism.

A Howell–Jolly body is seen within a red cell. There are target cells and acanthocytes.

The clinical significance of an absent spleen is the associated increased risk of life-threatening infection. The risk is greatest in children under 5 years of age and where there is a serious underlying medical disorder such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma or thalassaemia. Most infections occur within 2 years of splenectomy but fulminating infection can strike at any stage. In most cases infection is with encapsulated bacteria, notably Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis. In temperate regions more than half of serious infections are caused by the pneumococcus, with high mortality. Splenectomised patients have an increased susceptibility to severe malaria. Prophylaxis against such infections is the best approach and recommendations for the management of asplenic patients are shown in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2

Management recommendations in the asplenic patient

| Immunisation1 | Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae type B, group C meningococcus, influenza |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis2 | Oral phenoxymethylpenicillin or erythromycin |

| Prompt treatment of infection | Patients need systemic antibiotics and urgent admission to hospital |

| Medicalert disc or card | Detailing asplenic state and medical contacts |

| Avoid travel to high-risk malarial areas |

1Where possible at least 2 weeks prior to splenectomy. Reimmunisation is usually required, the timing determined by measurement of specific antibody levels.

2The duration of antibiotic prophylaxis is controversial but should generally be ‘lifelong’.

Hypersplenism

The pancytopenia of hypersplenism is probably induced by three contributory mechanisms:

Hypervolaemia consequent upon a disproportionately expanded plasma volume filling the vascular space of the enlarged spleen and the splanchnic bed.

Hypervolaemia consequent upon a disproportionately expanded plasma volume filling the vascular space of the enlarged spleen and the splanchnic bed.

Intrasplenic pooling of red cells which is increased from the normal 5–15% to 40% in moderate splenomegaly. This is accompanied by pooling of neutrophils and platelets.

Intrasplenic pooling of red cells which is increased from the normal 5–15% to 40% in moderate splenomegaly. This is accompanied by pooling of neutrophils and platelets.