Chapter 21 The special senses

Disorders of the ear, nose and throat

The Ear

Anatomy and physiology

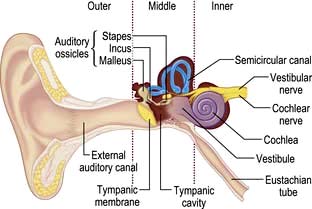

The ear can be divided into three parts: outer, middle and inner (Fig. 21.1).

The inner ear contains the cochlea for hearing and the vestibule and semicircular canals for balance. There is a semicircular canal arranged in each body plane and these are stimulated by rotatory movement. The facial, cochlear and vestibular nerves emerge from the inner ear and run through the internal acoustic meatus to the brainstem (see Fig. 22.7, p. 1076).

Common disorders

The discharging ear (otorrhoea)

Discharge from the ear is usually due to infection of the outer or middle ear.

Hearing loss

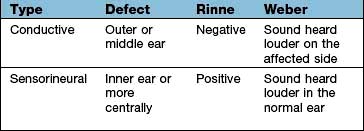

Deafness can be conductive or sensorineural and these can be differentiated at the bedside by the Rinne and the Weber tests (Box 21.1) or with pure-tone audiometry. Conductive hearing loss has many causes (Table 21.1) but wax is the commonest.

| Conductive | Sensorineural |

|---|---|

|

External meatus |

Congenital |

|

WaxForeign bodyOtitis externaChronic suppurationDrum |

Pendred’s syndrome (see p. 962) |

|

Long QT syndrome |

|

|

Björnstad’s syndrome (pili torti) |

|

|

End organ |

|

|

Advancing ageOccupational acoustic traumaMénière’s diseaseDrugs (e.g. gentamicin, furosemide) |

|

|

Perforation/trauma |

|

|

Middle ear |

|

|

Otosclerosis |

|

|

Eighth nerve lesions |

|

|

Acoustic neuroma |

|

|

|

Cranial trauma |

|

|

Inflammatory lesions: |

|

|

Tuberculous meningitis |

|

|

Sarcoidosis |

|

|

Neurosyphilis |

|

|

Carcinomatous meningitis |

|

|

Brainstem lesions (rare) |

|

|

Multiple sclerosis |

|

|

Infarction |

Normally a tuning fork, 512 Hz, will be heard as louder if held next to the ear (i.e. air conduction) than it will if placed on the mastoid bone (Rinne positive).

Normally a tuning fork, 512 Hz, will be heard as louder if held next to the ear (i.e. air conduction) than it will if placed on the mastoid bone (Rinne positive).

If the tuning fork is perceived louder when placed on the mastoid (i.e. via bone conduction), then a defect in the conducting mechanism of the external or middle ear is present (true Rinne negative).

If the tuning fork is perceived louder when placed on the mastoid (i.e. via bone conduction), then a defect in the conducting mechanism of the external or middle ear is present (true Rinne negative).

Presbycusis

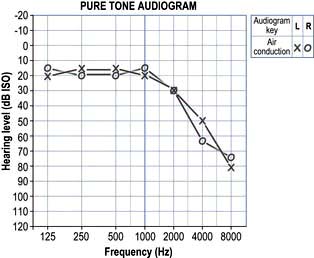

This is the commonest cause of deafness. It is a degenerative disorder of the cochlea and is typically seen in old age. It can be due to the loss of outer hair cells (sensory), loss of the ganglion cells (neural), strial atrophy (metabolic) or it can be a mixed picture. Ageing itself does not cause outer hair cell loss but environmental noise toxicity over the years is a major factor. The onset is gradual and the higher frequencies are affected most (Fig. 21.2). Speech has two components: low frequencies (vowels) and high frequencies (consonants). When the consonants are lost, speech loses its intelligibility. Increasing the volume merely increases the low frequencies and the characteristic response of ‘Don’t shout. I’m not deaf!’

Noise trauma

Cochlear damage can occur, e.g. when shooting without ear protectors or from industrial noise (see p. 935), and characteristically has a loss at 4 kHz.

Acoustic neuroma

This is a slow-growing benign schwannoma of the vestibular nerve (see p. 1076) which can present with progressive sensorineural hearing loss. Any patient with an asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss or sudden sensorineural hearing loss should be investigated, e.g. with an MRI scan.

Vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

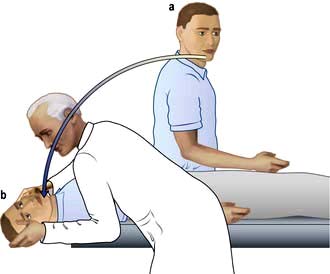

BPPV is thought to be due to loose otoliths in the semicircular canals, commonly the posterior canal. Positional vertigo is precipitated by head movements, usually to a particular position, and often occurs when turning in bed or on sitting up. The onset is typically sudden and distressing. The vertigo lasts seconds or minutes and the phenomenon becomes less severe on repeated movements (fatigue). There is no serious underlying cause but it sometimes follows vestibular neuronitis (see p. 1079), head injury or ear infection.

Diagnosis is made on the basis of the history and by the Hallpike manoeuvre (Fig 21.3). A positive Hallpike test confirms BPPV, which can be cured in over 90% of cases by the Epley manoeuvre. This involves gentle but specific manipulation and rotation of the patient’s head to shift the loose otoliths from the semicircular canals.

The nose

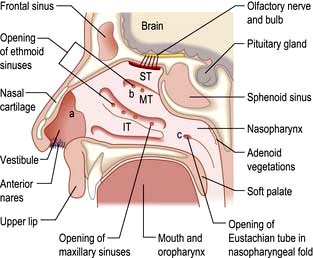

Anatomy and physiology (Fig. 21.4)

The function of the nose is to facilitate smell and respiration:

Smell is a sensation conveyed by the olfactory epithelium in the roof of the nose. The olfactory epithelium is supplied by the first cranial nerve (see p. 1071).

Smell is a sensation conveyed by the olfactory epithelium in the roof of the nose. The olfactory epithelium is supplied by the first cranial nerve (see p. 1071).

The nose also filters, moistens and warms inspired air and in doing so assists the normal process of respiration.

The nose also filters, moistens and warms inspired air and in doing so assists the normal process of respiration.

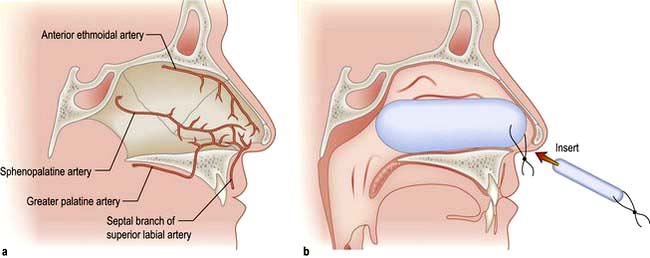

The blood supply of the nose is derived from branches of both the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal carotid artery supplies the upper nose via the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries. The external carotid artery supplies the posterior and inferior portion of the nose via the superior labial artery, greater palatine artery and sphenopalatine artery. On the anterior nasal septum is an area of confluence of these vessels (Little’s area) (Fig. 21.5a).

Common disorders

Epistaxis

Nose bleeds vary in severity from minor to life-threatening. Little’s area (Fig. 21.5a) is a frequent site of nasal haemorrhage. First aid measures should be administered immediately, including external digital compression of the anterior lower portion of the external nose, ice packs and leaning forward. The patient should be asked to avoid swallowing any blood running posteriorly as this causes gastric irritation and then nausea and vomiting.

Not infrequently, small recurrent epistaxes occur and these may require a visit to the emergency clinic for an examination and simple local anaesthetic cautery with a silver nitrate stick. If the bleeding continues profusely then resuscitation in the form of intravenous access, fluid replacement or blood, and oxygen can be administered. If further intervention is necessary, consideration should be given to intranasal cautery of the bleeding vessel, or intranasal packing using a variety of commercially available nasal packs (Fig. 21.5b). In addition to direct treatment of the epistaxis, a cause and appropriate treatment of a cause should be sought (Table 21.2).

|

Local |

Idiopathic |

|

Trauma – foreign bodies, nose-picking and nasal fractures |

|

|

Iatrogenic – surgery, intranasal steroids |

|

|

Neoplasm – nasal, paranasal sinus and nasopharyngeal tumours |

|

|

General |

Anticoagulants |

|

Coagulation disorders |

|

|

Hypertension |

|

|

Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome (familial haemorrhagic telangiectasia) |

Nasal obstruction

Rhinitis (see p. 808). If an allergen is identified, then allergen avoidance is the mainstay of treatment. Topical steroids and/or antihistamines can be tried. If severe, then oral antihistamines or referral to an allergy clinic for immunotherapy is warranted.

Rhinitis (see p. 808). If an allergen is identified, then allergen avoidance is the mainstay of treatment. Topical steroids and/or antihistamines can be tried. If severe, then oral antihistamines or referral to an allergy clinic for immunotherapy is warranted.

Septal deviation. Correction of this deviation can be undertaken surgically.

Septal deviation. Correction of this deviation can be undertaken surgically.

Nasal polyps. This condition occurs with inflammation and oedema of the sinus nasal mucosa. This oedematous mucosa prolapses into the nasal cavity and can cause significant nasal obstruction. In allergic rhinitis (see p. 798) the mucosa lining the nasal septum and inferior turbinates are swollen and a dark red or plum colour. Nasal polyps can be identified as glistening swellings which are not tender. Treatment with intranasal steroids helps but if polyps are large or unresponsive to medical treatment then surgery is necessary.

Nasal polyps. This condition occurs with inflammation and oedema of the sinus nasal mucosa. This oedematous mucosa prolapses into the nasal cavity and can cause significant nasal obstruction. In allergic rhinitis (see p. 798) the mucosa lining the nasal septum and inferior turbinates are swollen and a dark red or plum colour. Nasal polyps can be identified as glistening swellings which are not tender. Treatment with intranasal steroids helps but if polyps are large or unresponsive to medical treatment then surgery is necessary.

Foreign bodies. These are usually seen in children who present with unilateral nasal discharge. Clinical examination of the nose with a light source often reveals the foreign body, which requires removal either in clinic or in theatre with a general anaesthetic.

Foreign bodies. These are usually seen in children who present with unilateral nasal discharge. Clinical examination of the nose with a light source often reveals the foreign body, which requires removal either in clinic or in theatre with a general anaesthetic.

Sinonasal malignancy. This is extremely rare. The diagnosis must be considered if unusual unilateral symptoms are seen, including nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain, epiphora, cheek swelling, paraesthesia of the cheek and proptosis of the orbit.

Sinonasal malignancy. This is extremely rare. The diagnosis must be considered if unusual unilateral symptoms are seen, including nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain, epiphora, cheek swelling, paraesthesia of the cheek and proptosis of the orbit.

Sinusitis

If the symptoms of sinusitis are recurrent (Box 21.2) or complications such as orbital cellulitis arise, then an ENT opinion is appropriate and a CT scan of the paranasal sinuses is undertaken. Plain sinus X-rays are now rarely used to image the sinuses.

![]() Box 21.2

Box 21.2

Types of sinusitis

|

Acute |

Symptoms lasting 1 week to 1 month |

|

Recurrent acute |

>4 episodes of acute sinusitis per year |

|

Subacute |

Symptoms for 1–3 months |

|

Chronic |

Symptoms for >3 months |

CT scan of the sinuses or an MRI scan can demonstrate bony landmarks and soft tissue planes.

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is used for ventilation and drainage of the sinuses.

Anosmia

The throat

Anatomy and physiology

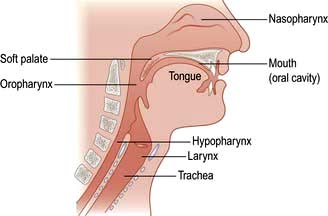

The throat can be considered as the oral cavity, the pharynx and the larynx (Fig. 21.6). The oral cavity extends from the lips to the tonsils. The pharynx can be divided into three areas:

The nasopharynx: extending from the posterior nasal openings to the soft palate

The nasopharynx: extending from the posterior nasal openings to the soft palate

The oropharynx: extending from the soft palate to the tip of the epiglottis

The oropharynx: extending from the soft palate to the tip of the epiglottis

The hypopharynx: extending from the tip of the epiglottis to just below the level of the cricoid cartilage where it is continuous with the oesophagus.

The hypopharynx: extending from the tip of the epiglottis to just below the level of the cricoid cartilage where it is continuous with the oesophagus.

Examination

Good illumination is essential. Look at teeth, gums, tongue, floor of mouth and oral cavity. Tonsils, soft palate and uvula are easily seen, and a gag reflex (see p. 1080) is present. The remainder of the pharynx and larynx can be inspected with a laryngeal mirror or flexible nasendoscope.

Examination of the neck for lymph nodes and other masses is also performed.

Common disorders

Hoarseness (dysphonia)

Acute-onset hoarseness

Hoarseness, in a smoker, is a danger sign. Any patient with a hoarse voice for over 6 weeks should be seen by an ENT surgeon. Other red flag symptoms are also to be enquired about and will require urgent laryngoscopy (Emergency Box 21.1). The voice may be deep, harsh and breathy indicating a mass on the vocal cord or it can be weak suggesting a paralysed left vocal cord secondary to mediastinal disease, e.g. bronchial carcinoma.

Stridor

Stridor or noisy breathing can be divided into:

Inspiratory: obstruction is at the level of the vocal cords or above

Inspiratory: obstruction is at the level of the vocal cords or above

Mixed (both inspiratory and expiratory): obstruction is in the subglottis or extrathoracic trachea

Mixed (both inspiratory and expiratory): obstruction is in the subglottis or extrathoracic trachea

Expiratory: obstruction is in the intrathoracic trachea or distal airways.

Expiratory: obstruction is in the intrathoracic trachea or distal airways.

All people with stridor, both paediatric and adult, are potentially at risk of asphyxiation and should be investigated fully. Severe stridor may be an indication for either intubation or a tracheostomy (Table 21.3).

Cuffed or uncuffed. A high-volume, low-pressure cuff is used to prevent aspiration and to allow positive-pressure ventilation.

Cuffed or uncuffed. A high-volume, low-pressure cuff is used to prevent aspiration and to allow positive-pressure ventilation.

Fenestrated or unfenestrated. A fenestrated cuff has a small hole on the greater curvature of the tube (both outer and inner) allowing air to escape upwards to the vocal cords and therefore the patient can speak. This tube often has a valve which allows air to enter from the stoma but closes on expiration, directing the air through the fenestration.

Fenestrated or unfenestrated. A fenestrated cuff has a small hole on the greater curvature of the tube (both outer and inner) allowing air to escape upwards to the vocal cords and therefore the patient can speak. This tube often has a valve which allows air to enter from the stoma but closes on expiration, directing the air through the fenestration.

Tonsillitis and pharyngitis

Quinsy

Indications for a tonsillectomy are shown in Table 21.4. This is carried out under a general anaesthetic and current surgical techniques include diathermy dissection, laser excision and coblation (using an ultrasonic dissecting probe). There are strong advocates for each technique and much will depend on the individual surgeon’s preference. Some departments now carry out tonsillectomy as a day case procedure as most reactionary bleeding will occur within the first 8 hours postoperatively.

Snoring

Snoring is due to vibration of soft tissue above the level of the larynx. It is a common condition (50% of 50-year-old males will snore to some extent) and can be considered to be related to obstruction of three potential areas: the nose, the palate or/and the hypopharynx (see Fig. 15.26).

The Epworth questionnaire (see Table 15.11) can assist in the discrimination of sleep apnoea from simple snoring. People with a history of habitual, non-positional, heroic (can be heard through a wall) snoring require a full ENT examination and can be investigated by sleep nasendoscopy in which a sedated, snoring patient has a flexible nasendoscope inserted to identify the source of vibration.

Nasal pathology such as polyps can be removed surgically with good results and most patients will benefit from lifestyle changes such as weight loss. Stiffening or shortening the soft palate via surgery, often using a laser, can help for palatal snorers but hypopharyngeal snorers require either a dental prosthesis at night to hold the mandible forward or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) via a mask (see p. 818).

FURTHER READING

Dhillon RS, East CA. Ear, Nose and Throat and Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

Roland NJ, McRae RD, McCombe AW. Key Topics in Otolaryngology, 2nd edn. London: Bios Scientific Publishers; 2001.

Warner G, Burgess A, Patel S et al. Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Dysphagia

Difficulty in swallowing is a common symptom but can be the presenting feature of carcinoma of the pharynx and therefore requires investigation. Dysphagia (see p. 237) occurs because of any lesion between the throat and stomach. The two conditions described here are the ones usually dealt with by ENT departments. Gastroenterology departments see causes further down the gullet.

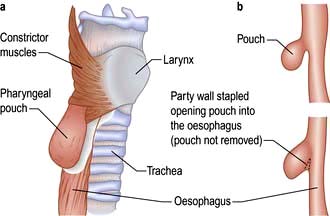

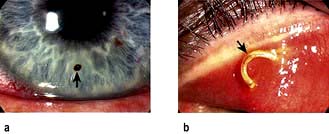

A pharyngeal pouch is a herniation of mucosa through the fibres of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle (cricopharyngeus) (Fig. 21.7a). An area of weakness known as Killian’s dehiscence allows a pulsion diverticulum to form. This will collect food, which may regurgitate into the mouth or even down to the lungs at night with secondary pneumonia. Diagnosis is made with a barium swallow and treatment is surgical, either via an external approach through the neck where the pouch is excised or more commonly endoscopically with stapling of the party wall (Fig. 21.7b).

Disorders of the eye

Applied anatomy and physiology

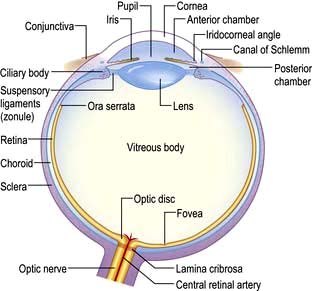

The average length of the human eye is 24 mm. It is essentially made up of two segments:

The anterior, smaller segment is transparent and coated by the cornea; its radius is approximately 8 mm

The anterior, smaller segment is transparent and coated by the cornea; its radius is approximately 8 mm

The larger posterior segment is coated by the opaque sclera and is approximately 12 mm in radius.

The larger posterior segment is coated by the opaque sclera and is approximately 12 mm in radius.

Anatomically the cornea is made up of five layers:

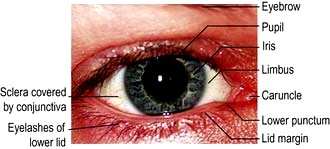

The anterior chamber is the space between the cornea and the iris, and is filled with aqueous humour (Fig. 21.8). This fluid is produced by the ciliary body (2 µL/min) and provides nutrients and oxygen to the avascular cornea. The outflow of aqueous humour is through the trabecular meshwork and canal of Schlemm adjacent to the limbus. Any factor which impedes its outflow will increase the intraocular pressure. The upper range of normal for intraocular pressure is 21 mmHg.

The uveal tract is made up of the iris anteriorly, the ciliary body and the choroid.

The vitreous humour fills the cavity between the retina and the lens.

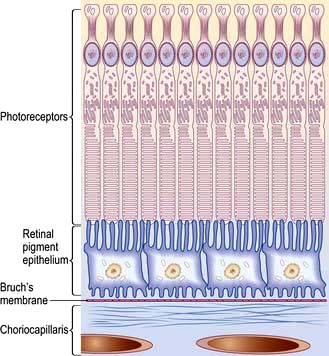

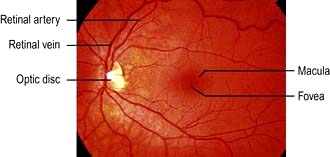

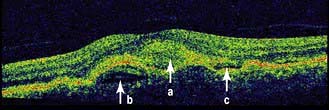

The retina is a multi-layered structure. The metabolically active region of the retina is represented in Figure 21.9. There are two types of photoreceptors in the retina, rods and cones. There are approximately 6 million cones mainly confined to the macula and these are responsible for detailed central vision and colour vision. The peripheral retina has around 125 million rods that are responsible for peripheral vision. The axons of the ganglion cells form the optic nerve (or disc) of the eye (Fig. 21.10).

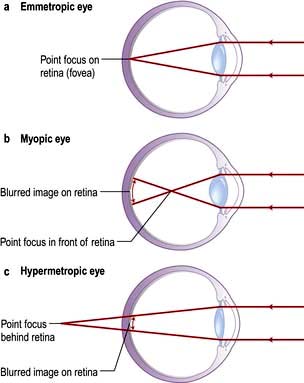

Refractive errors

The refraction of light in emmetropic (normal), myopic (short-sighted, negative lenses will correct) and hypermetropic (long-sighted, positive lenses will correct) eyes is shown in Figure 21.11.

Figure 21.11 Refraction. (a) Emmetropic (normal). (b) Myopic (short-sighted). (c) Hypermetropic (long-sighted).

Disorders of the lids

The lids afford protection to the eyes and help to distribute the tear film over the front surface of the globe. Excess tears are drained via the punctae and lacrimal system to the nose (Fig. 21.12). Malposition of the lids, factors which affect blinking or lacrimal drainage, can all cause problems.

Entropion. The lid margin rolls inwards so that the lashes are against the globe (Fig. 21.13a). The lashes act as a foreign body and cause irritation, leading to a red eye which can mimic conjunctivitis. Occasionally the constant rubbing of lashes against the cornea causes an abrasion. The commonest cause is ageing and surgery is usually required.

Dacryocystitis. Patients who have inflammation of the lacrimal sac usually present with a painful lump at the side of the nose adjacent to the lower lid (Fig. 21.13b). This should be treated with oral broad-spectrum antibiotics such as cefalexin, and patients should be watched carefully for signs of cellulitis. All patients should be referred to the ophthalmologist as some have an underlying mucocele or dilated sac, and will require surgery.

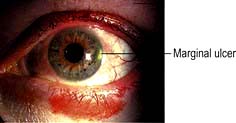

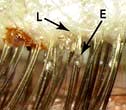

Blepharitis. This is an extremely common condition where inflammation of the lid margins may involve the lashes and lash follicles (Fig. 21.14a) resulting in styes, or inflammation and blockage of meibomian glands (Fig. 21.14b) leading to chalazion (Fig. 21.14c). Common underlying causes of blepharitis include meibomian gland dysfunction, seborrhoea and Staphylococcus aureus infection. Patients can be asymptomatic or complain of itchy, burning eyes because of tear film instability resulting from meibomian gland dysfunction. Staphylococcus aureus is frequently responsible for chronic blepharo-conjunctivitis and some patients may develop keratitis in the cornea (Fig. 21.15).

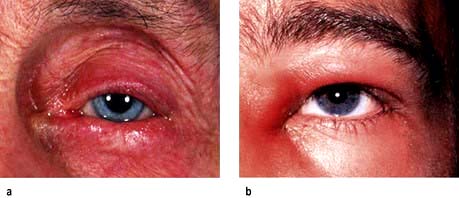

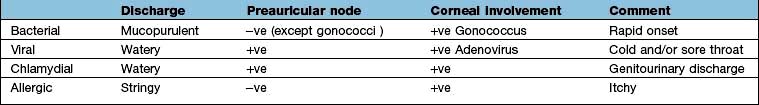

Conjunctivitis

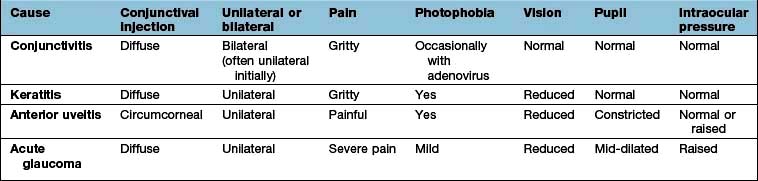

The commonest cause of a red eye, inflammation of the conjunctiva can arise from a number of causes, with viral, bacterial and allergic being the commonest. Common features in all types include soreness, redness and discharge, and in general the visual acuity is good. History should include the speed of onset of the inflammation, the colour and consistency of the discharge, whether the eye is itchy, and if there has been a recent history of a cold or sore throat. In the neonate it is vital to exclude gonococcal or chlamydial conjunctivitis associated with maternal sexually transmitted infection. The differential diagnosis of conjunctivitis is shown in Table 21.5.

Chlamydial conjunctivitis

Chlamydia trachomatis (see p. 164) is seen in developed countries as a sexually transmitted infection that is most prevalent in sexually active adolescents and young adults. Direct or indirect contact with genital secretions is the usual route of infections but shared eye cosmetics can also be involved. Neonatal chlamydial conjunctivitis is a notifiable disease in the UK and should be suspected in newborns with a red eye. Mothers should be asked about sexually transmitted infections.

Trachoma caused by the same organism, but not usually sexually transmitted, is found mainly in the tropics and the Middle East and is a very common cause of blindness in the world (see p. 133). Chronic conjunctival inflammation causes progressive scarring, trichiasis, entropion and subsequent corneal scarring which leads to severe visual impairment or blindness from corneal opacification or ulceration.

Clinical features

The onset of symptoms is slow, and patients may complain of mild discomfort for weeks. In these cases the red eye is associated with a scanty mucopurulent discharge and a palpable preauricular lymph node. In chronic cases it is not unusual to see superior corneal vascularization. In neonates the onset of the red eye is typically around 2 weeks after birth, whereas gonococcal conjunctivitis occurs within days of birth. Conjunctival swabs should be taken and a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) performed (p. 163) prior to commencement of treatment.

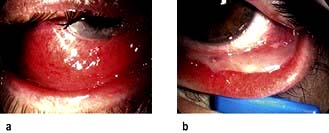

Viral conjunctivitis

Adenoviral conjunctivitis

This is highly contagious and can cause epidemics in communities. Transmission is through direct or indirect contact with infected individuals. The onset of symptoms may be preceded by a cold or flu-like symptoms. Inflammation is commonly associated with chemosis, lid oedema and a palpable preauricular lymph node. Some patients develop a membrane on the tarsal conjunctiva (Fig. 21.16) and haemorrhage on the bulbar conjunctiva. Viral conjunctivitis can cause deterioration in visual acuity owing to corneal involvement (focal areas of inflammation). In 50% of the patients the conjunctivitis is unilateral.

Herpes simplex conjunctivitis

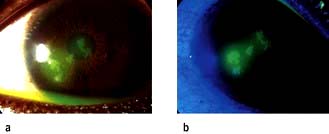

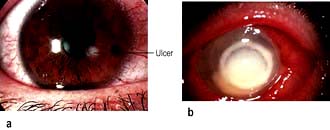

Primary ocular herpes simplex conjunctivitis is typically unilateral. It usually causes a palpable preauricular lymph node and cutaneous vesicles develop on the eyelids and the skin around the eyes in the majority of patients. Over 50% of these patients develop a dendritic corneal ulcer (Fig. 21.17). The organism responsible for this condition is the herpes simplex virus (HSV), which is usually HSV-1 but HSV-2 can give rise to ocular infection.

Allergic conjunctivitis

Seasonal/perennial conjunctivitis

Treatment

Reducing the allergen load (reducing dust, p. 825) is helpful. Medical treatment includes the use of antihistamine drops such as azelastine and emedastine together with topical mast cell-stabilizing agents such as sodium cromoglicate and nedocromil. Olopatadine (twice daily) has dual action and is very effective. Corticosteroid drops should be avoided. Oral antihistamines help the itching.

Corneal disorders

Trauma

Corneal abrasions

Clinical features

Symptoms include severe pain, due to exposure of the corneal nerve endings, lacrimation and inability to open the eye (blepharospasm). Blinking and eye movement can aggravate the pain and foreign body sensation. The visual acuity is usually reduced. Most cases will need topical anaesthetic drops such as oxybuprocaine or tetracaine to be administered before it is possible to examine the eye. The cornea should be inspected with a blue light after instillation of fluorescein drops. The orange dye will stain the area of the abrasion. Under blue light the abrasion lights up as green. Occasionally FBs can lodge on the undersurface of the upper lid and give rise to linear vertical abrasions. Eversion of the upper lid is necessary in all cases of abrasions (Fig. 21.18).

Corneal foreign body

Occasionally when something flies into the eye it gets stuck on the cornea (Fig. 21.19a). It may be associated with lacrimation and photophobia. Examination is best attempted following instillation of a topical anaesthetic and should include everting the upper lid (Fig. 21.19b). Corneal foreign bodies can usually be seen directly with a white light.

High-velocity trauma

Blunt trauma usually results in periorbital bruising and gross lid oedema, which can make examination to exclude perforating injury difficult. These patients should be referred to the ophthalmologist for a detailed ocular examination to exclude a perforation, retinal detachment or a traumatic hyphaema (Fig. 21.20).

Keratitis

Herpes simplex keratitis

Corneal epithelial cells infected with the virus eventually undergo lysis and form an ulcer which is typically dendritic in shape (Fig. 21.17). The ulcer stains with fluorescein and can be observed easily with a blue light. Topical immunosuppression, e.g. steroid drops, or systemic immunosuppression, e.g. AIDS, can lead to the centrifugal spread of the virus such that the ulcer increases in area and is referred to as a geographic ulcer. Recurrent attacks of HSV keratitis can be triggered by ultraviolet light, stress and menstruation. All these factors are responsible for activating the virus, which normally lies dormant in the ganglion of the Vth nerve.

Contact lens-related keratitis

A small number of contact lens wearers develop infective corneal ulcers which are potentially sight-threatening (Fig. 21.21). The organisms usually responsible include Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Patients should be referred to an ophthalmologist for scraping of the ulcer and commencement of antibiotic treatment.

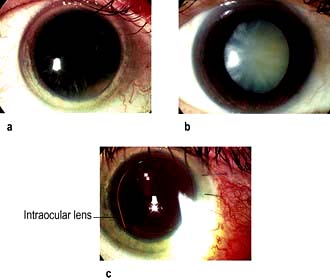

Cataracts

Cataract (Fig. 21.22a,b) is by far the commonest cause of preventable blindness in the world with an effective surgical treatment. In the UK, approximately 250 000 cataract operations are performed each year, making it the commonest surgical procedure.

Aetiology

Age-related opacification of the lens (cataract) is the commonest cause of visual impairment with 30% of people over 65 years having visual acuities below that required for driving (Snellen acuity less than 6/12). The common causes of cataracts are summarized in Table 21.6.

|

Congenital |

Maternal infection |

|

Familial |

|

|

Age |

Elderly |

|

Metabolic |

Diabetes, galactosaemia, hypocalcaemia, Wilson’s disease |

|

Drug-induced |

Corticosteroids, phenothiazines, miotics, amiodarone |

|

Traumatic |

Post-intraocular surgery |

|

Inflammatory |

Uveitis |

|

Disease associated |

Down’s syndrome |

|

Dystrophia myotonica |

|

|

Lowe’s syndrome |

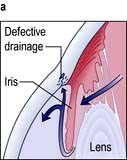

Glaucoma

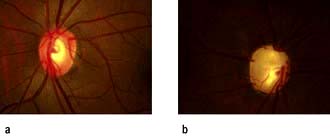

This is a group of diseases in which the pressure inside the eye is sufficiently elevated to cause optic nerve damage and result in visual field defects (Fig. 21.23). Normal intraocular pressure (IOP) is 10–21 mmHg. Some types of glaucoma can result in an IOP exceeding 70 mmHg. Glaucoma is the second commonest cause of blindness worldwide and the third commonest cause of blind registration in the UK.

Figure 21.23 (a) Normal optic disc and (b) glaucomatous optic disc. The central cup is enlarged and deepened.

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG)

Treatment

Beta-blockers such as timolol, carteolol and levobunolol reduce aqueous production and are the commonest prescribed topical agents. These drugs are contraindicated in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma or heart block.

Beta-blockers such as timolol, carteolol and levobunolol reduce aqueous production and are the commonest prescribed topical agents. These drugs are contraindicated in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma or heart block.

Prostaglandin analogues such as latanoprost and travoprost, increase aqueous outflow and are also used (alone or in combination with beta-blockers) for POAG as they can reduce IOP by 30%.

Prostaglandin analogues such as latanoprost and travoprost, increase aqueous outflow and are also used (alone or in combination with beta-blockers) for POAG as they can reduce IOP by 30%.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide reduce aqueous production and are available in both topical and oral form. In its oral form acetazolamide is the most potent drug for reducing ocular pressure. It should not be used in patients who have a sulphonamide allergy.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide reduce aqueous production and are available in both topical and oral form. In its oral form acetazolamide is the most potent drug for reducing ocular pressure. It should not be used in patients who have a sulphonamide allergy.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG)

Red eye and other signs and symptoms

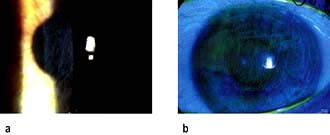

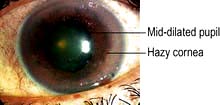

AACG causes sudden onset of a red painful eye and blurred vision. Patients become unwell with nausea and vomiting and complain of headache and severe ocular pain. The eye is injected, tender and feels hard. The cornea is hazy and the pupil is semi-dilated (Fig. 21.24). Table 21.7 shows the differential diagnosis of the acute red eye. Emergency Box 21.2 shows features that require urgent referral to an ophthalmologist.

Treatment

Prompt treatment is required to preserve sight and includes:

Uveitis

Uveitis is commonly encountered with ankylosing spondylitis and positive HLA-B27 (see p. 527), arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoid, tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, Behçet’s syndrome, lymphoma and viruses such as herpes, cytomegalovirus and HIV infection. In a number of patients no cause is found (idiopathic uveitis).

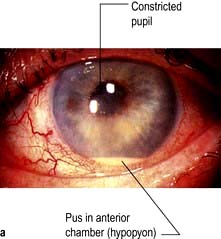

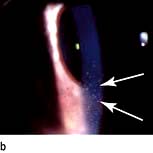

Anterior uveitis (iritis)

The classic presentation entails a triad of eye symptoms: redness, pain and photophobia. Vision can be normal or blurred depending on the degree of inflammation. The eye can be generally red or the injection can be localized to the limbus. The anterior chamber shows features consistent with inflammation including cells, keratic precipitates (KP) on the corneal endothelium, fibrin or hypopyon (pus), and the pupil may have adhered to the lens (posterior synechiae) (Fig. 21.25). The IOP may be normal or raised either due to cells clogging up the trabecular meshwork or posterior synechiae causing aqueous to build up behind the iris and force the iris against the trabecular meshwork and so reduce aqueous drainage.

Figure 21.25 Anterior uveitis. (a) Acute with hypopyon. (b) Showing keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelium.

Disorders of the retina

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO)

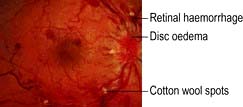

This usually leads to profound sudden painless loss of vision with thrombosis of the central retinal vein at or posterior to the lamina cribrosa where the optic nerve exits the globe. The thrombus causes obstruction to the outflow of blood leading to a rise in intravascular pressure. This results in dilated veins, retinal haemorrhage, cotton wool spots, and abnormal leakage of fluid from vessels resulting in retinal oedema (Fig. 21.26). In severe cases, an afferent papillary defect is present and this suggests the ischaemic variant.

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO)

This results in sudden painless severe loss of vision. Retinal arterial occlusion results in infarction of the inner two-thirds of the retina. The arteries become narrow and the retina becomes opaque and oedematous. A cherry red spot is seen at the fovea because the choroidal vasculature shows up through the thinnest part of the retina (Fig. 21.27). An afferent papillary defect is usually present.

Arteriosclerosis-related thrombosis is the most common cause of CRAO. Emboli from atheromas and diseased heart valves are other causes. Giant cell arteritis (see p. 543) must be excluded.

Treatment

People with CRAO should have a thorough medical evaluation to determine the aetiology of the emboli or thrombus. Some patients may present with transient loss of vision or amaurosis fugax (see p. 1098). All people with CRAO and amaurosis fugax should be started on oral aspirin if it is not medically contraindicated.

Retinal detachment

This causes a painless progressive visual field loss. The shadow corresponds to the area of detached retina. If the detachment affects the macula, central vision will be lost. Following a tear in the retina, fluid collects in the potential space between the sensory retina and the pigment epithelium (Fig. 21.28). Patients usually report a sudden onset of floaters often associated with flashes of light (photopsia) prior to the detachment. These patients should be referred to an ophthalmologist for a detailed fundal examination.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

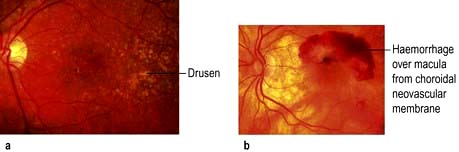

Non-exudative (dry) macular degeneration describes a painless and progressive loss of central vision. With age, lipofuscin deposits (drusen) are found between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch’s membrane (see Fig. 21.9 and Fig. 21.29a). Drusen may be hard or soft and there may be focal RPE detachment. Not all people with these changes will be affected visually but some develop distortion and blurring of their central vision. Extensive atrophy of RPE can occur (geographic atrophy).

Non-exudative (dry) macular degeneration describes a painless and progressive loss of central vision. With age, lipofuscin deposits (drusen) are found between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch’s membrane (see Fig. 21.9 and Fig. 21.29a). Drusen may be hard or soft and there may be focal RPE detachment. Not all people with these changes will be affected visually but some develop distortion and blurring of their central vision. Extensive atrophy of RPE can occur (geographic atrophy).

Exudative (wet) AMD (10% of cases) occurs with the development of abnormal subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in the region of the macula and causes severe central visual loss (Fig. 21.29b).

Exudative (wet) AMD (10% of cases) occurs with the development of abnormal subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in the region of the macula and causes severe central visual loss (Fig. 21.29b).

Treatment

Antivascular endothelial growth factors (anti-VEGF), such as ranibizumab and bevacizumab, are given by intravitreal injections with great success, although the latter is more expensive. The treatment course should be commenced as a matter of urgency as vision is maintained in up to 95% of patients and improves in approximately a third. Monthly monitoring with optical coherence tomography (OCT) is recommended (Fig. 21.30). Laser treatment and photodynamic therapy with verteporfin were the treatment of choice in the past for the treatment of wet AMD, but now have limited roles.

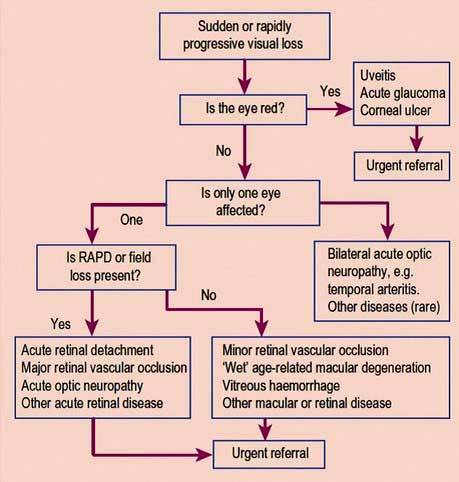

Visual loss

Every patient with unexplained sudden visual loss requires ophthalmic referral. The initial history and examination are summarized in Emergency Box 21.3.

![]() Emergency Box 21.3

Emergency Box 21.3

The initial history and examination in the patient presenting with sudden loss of vision

RAPD, relative afferent papillary defect.

(After: Pane A, Simcock P. Practical Ophthalmology. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005.)

The common causes of blindness are similar across the world (Box 21.3). In developing countries, trachoma due to Chlamydia trachomatis (see p. 164) is also a major cause, accounting for 10% of global blindness, as is onchocerciasis (river blindness, due to Onchocerca volvulus – see p. 154), which accounts for blindness in about 1 million people, although this is decreasing with treatment. In leprosy, 70% of patients have ocular involvement, and blindness occurs in 5–10% of these. Ocular involvement is common in cerebral malaria (see p. 144), although loss of vision is rare.

![]() Box 21.3 Loss of vision

Box 21.3 Loss of vision

summary

| Painless loss of vision | Painful loss of vision |

|---|---|

|

Cataract |

Acute angle-closure glaucoma |

|

Open-angle glaucoma |

Giant cell arteritis |

|

Retinal detachment |

Optic neuritis |

|

Central retinal vein occlusion |

Uveitis |

|

Central retinal artery occlusion |

|

|

Diabetic retinopathy |

|

|

Vitreous haemorrhage |

|

|

Posterior uveitis |

|

|

Age-related macular degeneration |

|

|

Optic nerve compression |

|

|

Cerebral vascular disease |

|

HIV infection can produce uveitis but the major problem is severe opportunistic infection of the eye when the CD4 count falls (see p. 178) and HAART is not available.

Vitamin A deficiency and xerophthalmia affects millions each year; the WHO classification of xerophthalmia by ocular signs is shown in Table 5.10 (see p. 206).