Chapter 9. The ‘social admission’

Delirium330

Dementia338

Nursing home admissions339

Ethical issues and the elderly sick341

The emergency admission of patients with a terminal disease343

Introduction

The label of ‘social admission’, while acknowledging the issue of the home circumstances, is a disservice to this group of patients, as it inevitably means that less effort is paid to establishing exact diagnoses. In fact a pure ‘social’ admission – one in which the patient is medically stable but in which the care input has failed – is a rare event and the term is generally unhelpful:

• it suggests a non-urgent or elective admission

• it denies a medical cause for admission

• it discourages a full medical assessment

• it implies a ‘social’ solution to the problems

• it suggests the patient can soon be shifted to hotel-type care

• the term falls into the same category as the unhelpful ‘bed blocker’ or even ‘off legs and unable to cope’, in which the emphasis suggests the unwelcome nature of the admission, rather than the challenge of returning an elderly person to their home with improved health

Common Errors and Omissions in the Admission of Elderly Patients

Failure to obtain an adequate history

• Simple communication failure – patient too ill or too deaf to communicate

• Acute confusion/delirium

• Long-standing confusion

• Inadequate referral details, particularly from the deputising service or from a nursing home

Failure to establish a correct drug history

It is important to establish:

• what the patient’s doctors have prescribed

• what the patient has actually been taking

• when any changes in medication occurred

Common problems with the drug history include:

• new treatments that do not appear on a repeat prescription list

• tablet bottles that contain a mixed assortment of drugs

• medications that the patient does not consider to be a drug

— Etidronic acid (Didronel PMO®; ‘fizzy drink’)

— monthly (e.g. B12) or weekly (e.g. methotrexate) treatments

— insulin

• non-compliance with multi-drug regimens (more than three different medications)

• failing to mention p.r.n. drugs, especially analgesics

• confusion concerning the doses of diuretics and the correct use of inhaled medication

Failure to make an adequate review of the patient’s previous hospital records

Re-admissions in this age group are common. Hospital notes are helpful, but they can be difficult to track down. Some of the patient’s problems may have been identified already: examples include septicaemia due to known kidney stones or gallstones, recurrent angina or dizzy episodes due to arrhythmias, and falls due to alcohol abuse.

Inadequate nursing and medical assessment

• Failure to assess the musculoskeletal system

• Missed crush fracture of the spine

• Missed fracture of the long bones

• Missed joint infection

• Missed shoulder injury following a fall

• Missed broken skin over pressure areas

• Failure to diagnose ‘silent’ myocardial infarction

• Silent pneumonia

• Silent septicaemia

• Faecal impaction as a cause of worsening confusion in a patient with dementia

• Failure to take an alcohol history (alcohol problems in the elderly present with depression, confusion and falls)

Taking the History

Taking a History From the Patient

Elderly unwell patients often have considerable difficulty in recalling the time course of the symptoms that brought them into hospital. For many, the point at which new symptoms took over from the chronic symptoms of generalised ill health and multiple pathology will be far from clear. For many elderly patients the process of giving a history, often more than once when they are already feeling unwell, can be a considerable ordeal. The tendency is for staff to rush them rather than sit and listen (→Case Study 9.1).

• Every patient has his or her own life story and, with patience, you will learn more from them than they will from you

• Piece together the history and try and find something of the person rather than simply the ‘admission problem’

• In the elderly, you are more likely to encounter atypical symptoms in commonplace conditions: dizziness as a presentation of myocardial infarction; ‘off legs’ as a result of a urinary tract infection; acute confusion as a side-effect of a change in drug treatment

• It is important that efforts are not duplicated and that the patients are not subjected to unnecessary repetition

• It is critical to obtain a history from a third party: a close relative, a professional carer or from the patient’s GP

Case Study 9.1

An 84-year-old man was admitted under the chest physician with immobility due to painful feet. He was frustratingly slow to give a rambling history, but after having successful dermatological treatment to his cracked and fissured soles he slowly mobilised. He was referred for rehabilitation and seen briefly at the end of very rushed ward rounds as ‘… and just the sore-foot man waiting to go to elderly care’. On a less hectic round he mentioned that he, too, had worked in a hospital and proceeded with a detailed account to a chastened chest consultant about the 20 years he had spent nursing in one of the country’s earliest cardiothoracic surgical units, how fierce the matron was and, in his day, how precise the bed alignment had to be prior to consultant ward rounds.

Pain

It can be difficult to separate symptoms from different systems. The problem of referred pain and the inability of some elderly patients to describe and localise their pain clearly can make it challenging for the listener. Examples include band-like abdominal pain attributable to collapsed thoracic vertebrae, upper abdominal pain due to acute myocardial ischaemia with cardiac failure, and diffuse abdominal pain due to a strangulated femoral hernia. To complicate the issue, many patients have pre-existing chronic pain from joint degeneration, from poorly controlled angina and from chronic arthritis of the spine.

Taking a History From a Third Party

The patient’s description of the home circumstances and his level of dependence must be supported by evidence from other sources. Without a detailed background, the assessment is seriously flawed:

• the patients may be unforthcoming because of confusion, anxiety or depression

• carers may have a different perspective on the situation

• late information cannot contribute to the critical initial diagnostic process and will probably delay the eventual discharge

Where to go for information

1. Relatives

2. The previous hospital medical and nursing notes

3. GP – early liaison with primary care will save a lot of time

4. Community nurse

5. Nursing home staff

6. Health visitors

7. Neighbours

8. Home care services

9. Social services

Dealing with relatives

• Many relatives fear that an elderly person may be written off at an early stage and may therefore be defensive about their normal level of dependence. Just because someone is 85 years old, it is wrong to assume that either the relatives or the patient will take a philosophical view about having had a ‘good innings’. Some of the most serious allegations of substandard care concern this area. Relatives often assume that, in the chaos of an acute unit, the elderly are given lower priority.

• Be sure who you are dealing with and what input they have in the care of the patient. It is not helpful to have an early detailed discussion with a niece who happens to be on the ward, before speaking to the daughter who has been sacrificing her sanity and her marriage to look after her confused elderly father for the past 5 years.

• Be sensitive to family dynamics, particularly in the issues of chronic dependence and dementia. The admission may have been the culmination of months of severe family stress in trying to cope with an increasingly difficult situation. The elderly spouses of patients with dementia often show evidence of significant stress-induced ill health. A straightforward and tactful information-gathering exercise is all that is needed in the early stages.

Liaising with the medical staff

Communication with the admitting doctors is of paramount importance in the management of the elderly. Apart from minimising the ordeal for the patient of repeating the same information to different staff members, there is critical information that must be shared at the outset:

• the patient’s baseline level of dependency

• the presence and time course of any confusion

• any suspicion of a head injury or a fracture

• the relatives’ main immediate concerns

• any particular risk of falling

1. Establish the depth of personal knowledge. Is the history from a third party due to personal familiarity with the patient, or is it hearsay?

2. When was the patient last well, and from that point how did the symptoms first develop, giving an approximate order?

3. What is the level of dependence and when did this change?

4. Establish the usual mental state and if there is a component of confusion/loss of short-term memory – when did it first develop, and how has it progressed or changed over time?

5. When you are doing your assessment, try to picture the patient in their own environment.

Falls

Falls are a common and important cause for acute medical admission. Almost 10% of patients aged 70 years and over will attend the Accident & Emergency Department at least once per year with injuries caused by a fall and a third of these will be admitted to hospital. Apart from a 10% risk of a fracture, falls have long-term consequences, particularly if they are recurrent:

• they lead to loss of confidence

• they are a threat to independence, particularly when they are recurrent

• hospital admission after a fall often triggers a slow general decline

In spite of their importance, patients are often not adequately assessed to establish the causes or the effects of their fall. Many will have attended on several previous occasions: a first-time faller has a greater than 50% chance of falling again within 12 months. In a significant proportion, the cause is reversible or the risk factors can be reduced.

The Cause of Falls

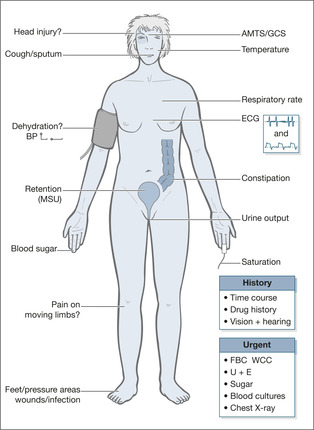

Fig. 9.1 and the following case studies illustrate the many factors that increase the risk of falls.

|

| Fig. 9.1 |

Most falls are caused by a combination of internal problems with balance, vision and posture, and external factors such as loose rugs, poor lighting and cluttered living space. The fall may be triggered by new medication leading to dizziness or confusion, or the effects of an intercurrent acute illness such as anaemia, heart failure or infection. Case Studies 9.2 illustrate such falls.

Case Studies 9.2

CASE 1

A 90-year-old-woman was started on the antidepressant, dothiepin: one tablet in the morning and two at night. She was also already taking atenolol 100mgHg a day, beta-blocker eyedrops and bendrofluazide. She had fallen and lain against the radiator, suffering a full-thickness burn to the right shoulder. On admission, her systolic blood pressure fell by 30 mmHg when she stood up from lying, associated with unsteadiness. She was otherwise well.

• Drug treatment is a common and treatable factor in falls

• Half of all elderly fallers cannot get back on their feet unaided

CASE 2

An 86-year-old woman was visiting her daughter at Christmas. She tripped in her bedroom and was in the line of a fan-heater. She was unable to move and suffered extensive burns to both lower legs.

• Falls are more common in unfamiliar surroundings, particularly those encountered when staying in cluttered or poorly lit spare rooms. People become used to their own frayed carpets and unsafe stairs, but these pose a threat to an elderly guest.

CASE 3

An 83-year-old man was admitted having been found on the floor with extensive occipital bruising. He had signs of a chest infection, but with treatment made a good recovery. Mobilisation, however, was very slow. He had generalised stiffness, a tremor and was very reluctant to move his feet due to fear of falling. A diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease was made and he was started on treatment.

Falls are common in Parkinson’s disease:

• patients tend to topple backwards

• they are slow to correct any imbalance

• there is often an associated postural hypotension

Patients will be admitted after a fall if:

• they fail to make a full recovery

• they have injured themselves

• they are in need of care that is not available at home

• a serious medical cause for the fall is suspected

Assessment After a Fall

Critical nursing tasks in assessment after a fall

Ensure the safety of the patient: ABCDE

Assess the vital signs and, if the patient is acutely ill, correct oxygen saturation, exclude hypoglycaemia, examine the pulse for bradycardia or tachycardia and measure the core temperature (hypothermia or fever). Always search for postural hypotension: a fall in the systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or more on standing upright (postural changes can be identified in the immobile from recordings taken when the patient sits up with the feet dependent over the side of the bed).

Look for injury

Pain is the main clue to injury, although acute confusion can mask pain completely. Note the sites of pain – they will need to be X-rayed if there is tenderness, deformity or swelling. Inspect the scalp for bruising, look behind the ears (Battle’s sign; →p. 106). Is there bruising around the hips? Look for pain on moving the wrists, shoulders, hips and elbows. Pleuritic pain may be due to fractured ribs. Deep pain in the lower back or groin is seen after pelvic fractures. If the patient has been lying in one position, there may be soft tissue pressure damage (bruising, discolouration and swelling) or burns.

If there is any pain around the neck or radiating round to the jaw – consider high cervical spine injuries (fractures can occur here in the elderly even with minor, low impact falls). CT of the cervical spine may be necessary.

Has this been a stroke?

Examine for one-sided weakness, facial droop or an obvious speech disorder. Confusion must not be confused with dysphasia. If a stroke is suspected, check the safety of the airway and of the swallow.

Arrange for an urgent ECG and cardiac monitor

This is to exclude a myocardial infarction or arrhythmia as the cause of the fall.

How to identify postural hypotension

The supine blood pressure is the value obtained after the patient has been lying quietly for 10 minutes. The standing blood pressure is the value obtained after the patient has been standing for 5 minutes. A drop in the systolic pressure of 20 or more or if the systolic pressure falls below 90 – particularly if accompanied by symptoms – indicates postural hypotension. The change in posture can also be accompanied by a marked increase in heart rate (by 30 or more bpm or to a rate > 120 bpm) which may also be associated with symptoms of dizziness and can be the culprit in some cases of syncope.

Important nursing tasks in assessment after a fall

Obtain an adequate history

• What were the circumstances? A fall, often forwards and causing facial injury, in which there is no warning and no loss of consciousness, suggests a drop attack. A ‘draining away’, particularly on standing with greying vision and fading voices, suggests syncope. It should be remembered that the elderly may not realise that they have lost consciousness and can have significant postural hypotension in the absence of symptoms. Dizziness with the room spinning, especially if triggered by sudden turning or neck extension, suggests vertigo. If the patient has acute vertigo and cannot stand without support, and particularly if there is also slurring of the speech and focal weakness, a posterior circulation stroke is the likely cause. Head injuries, particularly in males, are frequently associated with excessive alcohol intake.

• What is the drug history? The main culprits are nitrates, diuretics and antihypertensives – all causing postural hypotension – and psychotropics, notably long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g. nitrazepam), anticonvulsants and antidepressants, affecting balance and causing drowsiness.

Assess mobility

• Establish the patient’s existing mobility and cross-check their account with that of a relative: patients often overestimate their usual level of function.

• For a more objective assessment, there are three simple tests that can be tried once the patient has recovered from the immediate effects of the fall.

1. ‘Get up and go’ – the patient who can rise from a chair, stand steadily, walk across the ward, then turn and return to the chair without help does not have an immediate problem with mobility or balance.

2. Can the patient stand on one leg for 10 s? This will give a rapid global assessment of balance, power in the lower limbs and difficulty with weight bearing due to, say, problems with arthritic knees.

3. Does the patient stop walking when he talks? Patients who are beginning to find mobility an increasing problem, for whatever reason, have to marshal their resources when dealing with the challenge of walking. This is apparent if a conversation is started while the patient is on the move – they will stop walking in order to talk.

Assess cognitive function

This is an important part of any assessment in the elderly patient, but in the particular case of recurrent or unexplained falls, cognitive impairment will have a profound effect on the plans for discharge.

The AMTS (→Box 9.1) is simple to administer: a score of less than 7 out of 10, assuming this is not due to a simple communication problem, suggests cognitive impairment. The next step is to establish from the relatives’ history whether this is a recent or long-standing problem.

Box 9.1

1. How old are you now?

2. What time is it now (to the nearest hour)?

3. I will give you an address and ask you to repeat it later on: 42 West Street

4. What year is it now?

5. Can you tell me where you are now?

6. Can you tell me who (two persons) these people are?

7. Can you tell me the date of your birthday (day and month)?

8. What were the dates of the First World War?

9. Who is on the throne at present?

10. Can you count from 20 to 1 backwards?

Speak to the carers and close family

• Obtain an overall picture of the patient in his home, with an emphasis on mobility, vision and the immediate domestic environment. Confirm the drug (and alcohol) history. Check the input from family and professional carers.

• Has there been evidence of cognitive impairment: memory loss and difficulty with complex tasks?

Additional assessment on examination

• Look at the feet and lower limbs. Examine for generalised arthritis, particularly of the knees. Knees that are swollen, arthritic and stiff are often associated with thigh muscles that are weak and wasted through disuse. Is there generalised weakness of the legs? Are the feet well cared for or are they misshapen, with overlapping toes, bunions, painful fissures and huge uncut nails?

• Assess the hearing and vision. Sensory deprivation leads to loss of balance, a loss of the compensatory mechanisms needed to maintain equilibrium, and a reduction in the level of self-confidence. Ensure hearing aids and glasses are brought in soon after admission.

• Evaluate and localise any pain and ensure appropriate analgesics are prescribed and given.

Answering Relatives’ Questions in Patients Who Fall

Why do the falls keep occurring? The majority of elderly patients who fall will fall again. However, while some risk factors cannot be corrected some, such as drug side-effects and environmental factors, can be addressed.

What can we do to prevent it? Our assessment will identify any reversible medical cause for the falls, and part of the rehabilitation will involve an evaluation of the situation at home.

Shouldn’t he now be in a nursing home – we cannot possibly take him into our house? One of the outcomes of this admission will be an assessment of the domestic situation, to assess the patient’s personal needs and to look at what support is available. Any eventual discharge will take all these factors into account as well as your views and those of the patient.

Does he need all those tablets? We will take this opportunity to re-evaluate all his medication – what he is prescribed, what he actually takes and what he really needs.

Why did he fall in the ward? Patients who are unsteady on their feet are more likely to fall in unfamiliar surroundings, particularly if an acute illness has led to confusion. We will try to prevent further falls by treating the underlying problems and in the meantime it may be helpful to bring in glasses/supportive footwear/usual walking aids.

Can’t you use sedation or cot sides? Sedation or physical restraint are the absolute last resorts – and only then if the patient is a danger to himself. Their use causes increasing confusion and there is no evidence that they are effective in preventing falls: indeed, they may slow down mobilisation.

What are the chances of this happening again in hospital? Recurrent falls are quite common at this age, even if all possible precautions are taken. There is always a balance to be struck between safety and encouraging the patient to maintain his independence. There are effective ways of reducing the chances of falling again: a detailed risk assessment of all the factors which may be contributing to the falls, leading to a management plan to reduce these and special targeted exercise programmes to improve balance, gait, posture and muscle strength.

▪ Are the staffing levels appropriate for the dependence levels in your patients?

▪ Are your elderly patients assessed according to a protocol?

▪ How much unnecessary duplication is there?

▪ Are the relatives and carers interviewed on admission?

▪ Do you use an AMTS as routine in assessing the elderly?

▪ Can you identify the ‘high-risk faller’?

▪ Is there a protocol for the prevention of falls/use of cot sides?

▪ Have you audited falls on the acute ward?

▪ How safe is your ward for the elderly unsteady?

— bed to chair or commode

— chair to bathroom

— how cluttered is the space around the beds?

— how well do their pyjama bottoms fit!

▪ How soon after admission do you start planning for discharge?

Immobility

Increasing immobility can have many important causes, as the following case studies illustrate (→Case Study 9.3, Case Study 9.4, Case Studies 9.5 and Case Study 9.6).

Case Study 9.3

An 86-year-old woman presented with an 8-week history of increasing immobility, anorexia and reduced fluid intake. She had previous admissions to elderly care for respite care. She denied any particular complaints and said she was able to walk with a stick.

On initial assessment, she appeared frail and cachectic. Her AMTS was 4/10. She had a productive-sounding cough and evidence of left lower lobe pneumonia.

The initial diagnosis was ‘poor mobility and a chest infection’.

Immediate blood tests showed that she was anaemic and also had abnormal liver function tests. An ultrasound showed a large right-sided renal cancer, with secondary spread to the liver.

• When elderly patients become ill, their history cannot be relied on.

• Malignant disease rather than ‘frailty of old age’ is often the cause of progressive deterioration.

• Early investigations mean that an appropriate management plan can be instituted soon after admission.

Case Study 9.4

A 78-year-old widower took to his bed because he was too weak to walk. His only complaint was of burning on passing urine. He was unable to recall any of his medication, but his daughter later provided a list, which included prednisolone, oral nitrates and atenolol.

Coliform bacteria were cultured from his urine and blood.Within 4 days of starting antibiotics, he was feeling well and was fully mobile.

Infection, particularly urinary infection, can lead to generalised ill health. It is important to identify those regular medications that must not be stopped suddenly.These may include:

• steroids (acute steroid insufficiency)

• beta-blockers (rebound angina)

• anticonvulsants (recurrence of fits)

• benzodiazepines (withdrawal syndromes)

Case Studies 9.5

CASE 1

An 85-year-old woman with Alzheimer’s disease came to the AED and had her dislocated shoulder reduced under sedation with i.v. diazepam.Two days later, she was admitted with an impaired consciousness level, having taken to her bed with an aspiration pneumonia. She had a productive cough and GCS of 5. She responded to physiotherapy and i.v. antibiotics.

• Patients’ psychosocial circumstances must be assessed fully before discharge.

• There is a major risk in sending an elderly infirm woman with dementia home from hospital immediately after sedation.

CASE 2

A 73-year-old diabetic woman with a previous history of strokes was admitted with a gradual deterioration, lethargy and increasing immobility. She was a ‘dead weight’ and her husband was unable to cope. Nothing specific found. She was transferred to elderly care where she was noted to be on two sedatives, antidepressants and nitrazepam.These were gradually withdrawn. She made a spontaneous recovery and was rapidly (over 3–4 days) able to mobilise with a zimmer frame and support.

• In any immobile patient, the drug history is critical.

• A third of admissions in the elderly are related to drug toxicity.

• Polypharmacy increases the chances of interactions, drug duplications and non-compliance.

Case Study 9.6

An 80-year-old man with a known history of chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation was admitted with sudden generalised deterioration and confusion.

On assessment, his AMTS was unrecordable, he was unable to stand unsupported and was incontinent of urine. His speech was slurred and he was slumped in bed with a respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min. Blood pressure was 235/122 mmHg and his oxygen saturations were 85%. His initial blood tests showed dehydration.The diagnosis was ‘acute confusion’.

Two hours after admission he was found on the floor, having fallen from his bed and bruised his shoulder.The next morning on reassessment he appeared dysphasic rather than confused and was slumped to one side with definite evidence of unilateral weakness. Further blood tests showed high digoxin levels but nothing else of note.

By 24h, his GCS had fallen from 15 on admission to 6, and his respiration had become laboured and irregular (Cheyne–Stokes respiration). An urgent CT scan showed a large cerebral bleed related to his severe hypertension. A diagnosis of stroke complicated by aspiration pneumonia was made. He was started on i.v. ampicillin and metronidazole.The neurosurgeons advised that there was no indication for surgery.

By the eighth day of admission, he was sitting up cheerfully in bed with mild functional impairment and was starting to mobilise. His blood pressure was controlled with cautious use of antihypertensives.

• Stroke presents as confusion.

• Dysphasia may be mislabelled as confusion.

• Always look for evidence of weakness down one side (the family will often notice this first).

• Outcomes are difficult to predict in the elderly, who can have excellent powers of recovery (patients who reach 80 years old have a proven track record of survival!).

‘Off legs and unable to cope’ is the commonplace label for immobility, and should be ignored. Immobility is either part of a slow global deterioration in function or, more commonly on the admitting ward, it occurs suddenly over days or weeks and signifies an acute illness of some form.

The common causes of recent onset immobility are:

• stroke

• Parkinson’s disease

• heart failure

• acute exacerbation of COPD

• musculoskeletal disease (arthritis and osteoporosis)

These may be accompanied or triggered by:

• depression or grief

• anxiety, especially associated with a fear of falling

• pain

• underlying cognitive impairment

Critical nursing tasks in assessing immobility

Immediate safety of the patient: ABCDE

• Exclude hypothermia: a core or tympanic membrane temperature < 35°C

— hypothermia causes confusion and incoordination

— triggers include alcohol and psychotropic drugs

— it can result in dehydration and pneumonia

— active rewarming is indicated

Assessing the cause: establish the full history

• From the patient and a third party

• Establish the sequence of events: acute/chronic/acute on chronic

• Acomprehensive list of medications

• What is the patient’s normal level of mobility?

— how did the immobility develop: progressive/sudden onset/stuttering?

— is there musculoskeletal disability?

— how are hearing, sight and balance?

— are there recurrent falls?

— have you access to previous nursing or medical notes?

Important nursing tasks in assessing immobility

Assess the overall condition

• Does the patient look well for their age (grooming/foot care/state and cleanliness of the skin)?

• Is there evidence of neglect (underweight/poor hygiene/chronic changes to the skin and feet)?

Is the patient in pain?

Pain, particularly on movement, leads to immobility and commonly arises from the musculoskeletal system – either chronic arthritis or vertebral collapse. Severe osteoporosis is a major cause of increasing immobility, with loss of height, spinal deformity and severe pain from fractures of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. When bones are osteoporotic, even minor falls can lead to fractures of the hip, wrist, pelvis and ribs.

▪ Assess the overall condition

▪ Is the patient in pain?

▪ Look at the areas of risk

▪ Look for evidence of malnutrition and dehydration

▪ Examine the patient’s mobility

▪ Is there any evidence of urinary incontinence?

▪ Should the patient be catheterised?

Look at the areas at risk

• Examine skin creases and groin

• Record any changes over the pressure areas

• Remove any dressings and note the findings

• Examine and record any areas of bruising, redness or tenderness

Look for evidence of malnutrition and dehydration

The risk factors for malnutrition are:

• poverty

• depression

• social isolation

• dementia

• recent bereavement

• anorexia

• ill-fitting dentures and sore mouth

There may be signs of vitamin and protein deficiency – but the main clue remains the patient’s weight: a BMI (weight in kg/height in metres squared) of less than 19 indicates likely malnutrition (to estimate height in the bed-bound or those who have lost height, double the distance from finger tip to mid sternum). These patients should be referred immediately for nutritional assessment and dietetic support.

Examine the patient’s mobility

Note: Remember the risk of postural hypotension.

• What do you anticipate from the history you have already?

• Is the patient well enough to try to stand?

• Can the patient sit up unsupported with good balance?

• Is there any obvious one-sided weakness in the face, arms or legs?

• Can the patient lift each foot, in turn, 3 in (8 cm) or more off the bed?

• Can the patient sit on the edge of the bed unsupported?

• Can the patient ‘get up and go’?

If there is evidence of urinary incontinence, what is the time course?

Long-standing incontinence. Chronic incontinence is common in the elderly, particularly those with cognitive impairment: one in five nursing home residents are incontinent during the day. However, even in established incontinence, there may be reversible causative factors such as immobility or overuse of diuretics. The acute admission provides an opportunity to review possible underlying causes.

Recent onset urinary incontinence. There are four mechanisms that can interact to result in acute urinary incontinence:

• Impaired cognition – this is seen in delirium, stroke and over-sedation, all of which are potentially reversible

• Reduced mobility – an elderly patient with bladder irritability may have to urinate every hour or so. Any cause of sudden immobility can therefore result in incontinence

• Excessive fluid challenge – overuse of diuretics or the excessive osmotic diuresis from uncontrolled diabetes can both overwhelm an ageing bladder and lead to temporary incontinence

• Bladder instability – a common problem in the elderly, the additional effect of urinary infection or faecal impaction on the bladder will produce urgency and incontinence

Should the patient be catheterised?

Catheterisation is associated with short-term complications, impairment of early mobilisation and reduced chances of regaining continence. Situations in which it may be justified include:

• terminal illness when there is distress from bladder distension or incontinence

• to allow healing when incontinence has produced skin excoriation or ulceration

• in critical illness in which measurements of the hourly urine output are required

• patients in coma

Delirium

Cognitive impairment is a common and challenging problem on the Acute Medical Unit, with current estimates that, among those over 65 years admitted as an emergency, it will be a significant issue in 20%. In half of these the picture is of chronic confusion (dementia) and in the other half there will either be an acute confusional state (delirium) occurring de novo, or a combination of long-standing confusion with a sudden worsening, coinciding with the admission to hospital.

Delirium occurs in around one in five elderly patients after admission to hospital:

• it carries a significant mortality risk

• it can mask pain and acute illness

• it delays rehabilitation and discharge

• it can take weeks to resolve

There are six important risk factors:

1. existing cognitive impairment

2. sight and hearing impairment

3. immobility

4. acute physical illness

5. dehydration

6. sleep deprivation

There are five major causes on the Acute Medical Unit:

1. infection

2. hypoxia

3. metabolic upset (particularly dehydration)

4. major organ failure

5. drug therapy

Principles of management

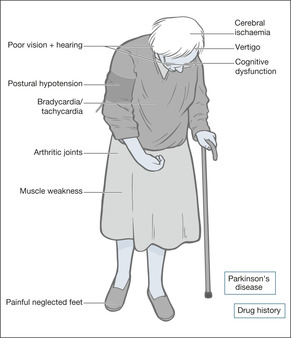

• Make an immediate comprehensive assessment (→Fig. 9.2)

• Establish exact baseline health and functional status

• Treat any acute medical condition

• Prevent deterioration in existing function through enforced immobility, lack of communication, unfamiliar surroundings

• Prevent infliction of harm through unnecessary drug therapy, neglect, falls or premature discharge from hospital

Case Studies 9.7 present some of the problems encountered with confused patients.

Case Studies 9.7

CASE 1

The patient was admitted to the Acute Medical Unit at midnight. She was not initially assessed, and at 01.00h she fell from the bed onto the floor, sustaining extensive superficial grazes above her eyes and an abrasion to her face. Subsequent examination showed an AMTS of 3/10 and evidence of recent urinary incontinence. She was restless and unable to give an account of herself, but was apyrexial. By the next day her respiratory rate had increased to 25 breaths/min, she had a wet, productive-sounding cough and remained incontinent of urine. She was sitting anxiously picking at the bedclothes and was clearly distressed but unable to say why.

With physiotherapy she produced green sputum.The head wounds healed uneventfully and she slowly returned over the subsequent few days to her previous state.

The diagnosis was of an initial urinary infection complicated by a fall.

Should cot sides have been used?

Probably not: there is little evidence that cot sides are helpful in acute confusion, indeed, they increase the potential height of any fall.The main value of cot sides is in combination with pillows to maintain a safe position, in patients with a depressed consciousness level.

History

It is important to obtain a history from a nursing home and relatives, although it is common for elderly women to have no close relatives available at the time of admission.

Should antibiotics be used blindly?

Antibiotics should not be given blindly in acute confusion and incontinence on the assumption that there may be a urinary tract infection.Treatment should be reserved for proven infection associated with any of the following:

• fever

• dysuria

• lower abdominal pain

• new incontinence

• frequency/urgency

Pneumonia can be difficult to recognise in the elderly, but an increased respiratory rate and a productive cough are sufficient evidence of infection to start antibiotics.

Alzheimer’s disease

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease have a low threshold for developing a super-added confusional state in response to even minor acute illnesses. Patients should not be sedated but they must be maintained in a safe environment to reduce the risk of self-injury through falling.

CASE 2

An 82-year-old woman with dementia was admitted to hospital ‘off legs and vomiting’. No history was available from the patient as her AMTS was 1/10. She was weak, incoherent and febrile.The day after admission, she became poorly responsive and more febrile.The patient then rallied and became brighter, but her speech was noted to be incomprehensible. She was, however, said to be ‘back to her normal self’.The patient was transferred to elderly care for rehabilitation.There she required full nursing care. On medical review, she was found to be dysphasic, with some receptive problems.The new diagnosis of a stroke was discussed with her son, who with great frustration said the family had been saying that all along but no one was listening.

Care must be taken with the label of dementia and particular attention must be paid to the preadmission functional level and to the family’s account of their relative’s normal state of health and of how the illness developed.

CASE 3

A 72-year-old woman was admitted with coffee-ground vomiting and hallucinations. She was also mildly dysphasic.The history was limited, but her hallucinations were addressed at the expense of her vomiting, and a referral was made to the psychogeriatricians, who felt her social circumstances needed sorting out. She was transferred to elderly care, where a subsequent endoscopy showed pyloric stenosis and significant ulceration.

The hallucinations had coincided with initiating opiate analgesia.This was stopped and at a later date fentanyl patches were effectively introduced for what turned out to be severe post-herpetic neuralgia. She mobilised well and after a successful home visit was discharged from hospital.

This patient did not undergo a comprehensive initial assessment. In her case there was a combination of physical conditions and cognitive impairment – these are impossible to sort out without full background information from a third party. In particular, there must always be a full drug history, which should include any sedation, anticonvulsants and analgesics, as these may accumulate, causing toxicity and contributing to confusion.

CASE 4

A 94-year-old woman who lives alone was found on the floor unable to get up. Apparently she had fallen before. On admission she was confused, with a productive cough, a temperature of 38.5°C and an AMTS of 2/10.The oxygen saturations were low, at 88%, and she had signs of a chest infection. She was treated with i.v. fluids and antibiotics, but remained confused.

Critical nursing tasks in assessing the confused elderly

The critical nursing tasks in the acutely confused elderly patient are similar to those in a seriously ill younger patient. Although there are differences in the way in which problems present, the essential priorities are the same: addressing basic resuscitation using the system ABCDE and maintaining the immediate safety of the patient.

Fig. 9.2 summarises the assessment of acute confusion.

Hypoxia

• The most common cause of hypoxic confusion in the elderly is pneumonia with sputum retention. The chest sounds wet on coughing, but the patient is often too weak to expectorate. Chest pain after a fall may be due to fractured ribs and can severely inhibit deep inspiration and coughing. The pain must be addressed before the patient can have effective chest physiotherapy. It is important to recognise that the pneumonia may be complicating another event: a fall with an unrecognised fracture or a stroke with aspiration. The only signs of pneumonia may be an increased respiratory rate and confusion; the temperature may be normal or only increase after admission.

• The other main cause of hypoxic confusion is acute LVF, which can be very difficult to distinguish from pneumonia or even COPD. Examination can be unhelpful in this age group, and chest films are difficult to interpret. Initial emergency management will often be a compromise by targeting both the heart and the lungs: combining nebulised bronchodilators and antibiotics with diuretics and nitrates.

Management of hypoxia

• Sit the patient up

• Encourage the patient to cough. If it sounds productive, arrange urgent physiotherapy. Ensure there is effective analgesia, without the risk of further sedation or confusion

• Administer oxygen to increase saturations to 90%

• Organise an ECG to exclude an acute myocardial infarction or arrhythmia (acute atrial fibrillation is very common in this age group)

• Patients should be catheterised if intensive diuretic therapy is planned, particularly as the confused patient is likely to be incontinent: it is kinder for the patient and the output can be accurately assessed during the critical first 24–48h

Hypoglycaemia

In this age group, hypoglycaemia is seen only in diabetic patients on insulin or (and) oral hypoglycaemics, and occasionally after a heavy drinking binge. Longer-acting oral hypoglycaemics such as glibenclamide and chlorpropamide are particularly dangerous in the elderly. If drug interaction with the oral hypoglycaemics is suspected (and it should be whenever a patient is taking four or more drugs), contact the ward pharmacist for advice.

Head injury

Head injuries are a very important cause of reversible confusion – a trivial injury can result in a subdural haemorrhage and the history will not be forthcoming in a delirious patient. If there is a fluctuating consciousness level or a progressive fall in the GCS, it is vital to consider a CT scan before the situation becomes irretrievable. Even the very elderly can benefit from neurosurgical intervention in the appropriate circumstances. Important clues, apart from the all important history, are facial bruising, scalp wounds, bruising behind the ears and ‘raccoon eyes’.

Hyponatraemia

Hyponatraemia (a low serum sodium) is a less pressing but nonetheless important and common cause of confusion in the elderly. It is often due to excessive urinary salt loss from diuretic therapy, particularly if the patient also loses excessive fluid, say from acute diarrhoea. The signs in these patients are of hypovolaemia (high pulse rate and postural hypotension) and treatment is with saline. This is not the only cause of hyponatraemia: in some patients it can be due to inappropriately high levels of ADH – a hormone that stimulates the kidneys to retain salt-free water and hence dilute the blood. ADH secretion is vital as the normal response to dehydration, but in this group of patients the trigger for ADH secretion is either an adverse drug reaction (especially psychotropics) or, occasionally, cancer of the lung. Treatment of inappropriate ADH secretion is with fluid restriction.

Important nursing tasks in assessing the confused elderly

Assess the degree of cognitive impairment

The AMTS is a tried and tested method to identify cognitive impairment. Provided the patient can hear and is not dysphasic, a score of 7 or less out of 10 signifies significant impairment. It does not distinguish between acute and chronic confusion; for this a full history is also required.

Exclude infection and dehydration

The main sources of infection are the chest, urine and soft tissues. Generalised infection, and even septicaemia, may have very non-specific findings in the elderly:

• increased respiratory rate of > 15 breaths/min

• tachycardia

• hypotension

• mild confusion

Patients with infected wounds may be confused because of the development of septicaemia or spreading soft tissue infection. Any wound should be fully exposed in a good light to determine and document its depth and extent, and to look for elements such as critical limb ischaemia or gas gangrene. In difficult cases it is preferable for the wounds to be exposed to a combined team of nursing staff and doctors. A management plan can then be produced on admission, rather than taking dressings down three or four times during the first 24h for a selection of doctors and nurses of varying expertise and experience.

• If there are skin breaks, wounds or ulcers that concern you, ensure that these are all accessible and highlighted on the consultant’s ward round.

Dehydration can be difficult to identify without blood tests showing increases in the urea and creatinine. The most reliable signs are:

• postural hypotension

• tachycardia

• decreased level of consciousness

• urine output of less than 50 ml/h

Assess constipation

In the elderly, faecal impaction causes acute confusion, worsens existing cognitive dysfunction and is a reversible factor in urinary incontinence. It can be suspected from a full history and stool chart, but can only be diagnosed by a combination of a rectal examination and an abdominal X-ray.

Make an assessment of the social circumstances and dependence

Gain information from both patient and carers – do not let the carers leave the ward until they have been seen, or telephone them at the end of the initial clerking for further information.

1. Does the patient live alone?

2. Does the patient care for someone else?

3. What is the degree of family and/or neighbour support?

4. Is the property secure?

5. Are there pets at home?

6. What are the levels of input?

— district nurse

— warden

— social services and meals on wheels

— home help

— voluntary help

— social worker

Dementia

Dementia commonly complicates acute medical conditions in the elderly: it obscures the immediate diagnosis, impairs recovery and has an obvious impact on planning for the patient’s discharge.

Sixteen percent of all women and 6% of all men who reach an average life expectancy will develop dementia – a rate equivalent to around one in five people over the age of 80 years. Of these, 80% will have Alzheimer’s disease, in which there is a progressive continuous deterioration; 10% will have multi-infarct dementia, in which the deterioration is stepwise punctuated by a series of mini-strokes; and 5% will have dementia against a background of Parkinson’s disease, in which the picture is complicated by immobility and drug-induced side-effects, often with hallucinations.

In some cases there will be another psychiatric disorder present: depression, acute anxiety or an alcohol-related problem. This will need to be recognised and addressed.

Complications of dementia that can occur in the Acute Medical Unit

Psychoses

These usually take the form of acute paranoia and can be triggered by any acute medical illness. Classically, they are seen after acute myocardial infarction. Patients become intensely suspicious of the staff and often accuse them of being plotters or poisoners. Mobile patients may actively try to flee from the ward to escape this ‘persecution’. Acute paranoid states need urgent psychiatric assessment and the warning signs require urgent action.

Aggression

This is also seen in dementia as a complication in acute illness, and may be a result of drug toxicity or dehydration. Treatment with sedation is usually unhelpful in the acute situation. Traditional management with haloperidol 2mg every 8h leads to drug accumulation, Parkinsonian side-effects and over-sedation. If there is no alternative for a severely disturbed patient, a short-acting benzodiazepine such as lorazepam is the drug of choice. Any prescription for sedation must be reviewed at least every 12h to ensure the patient is not over-sedated.

Nursing observations for a patient who has required sedation

• Hourly consciousness level: GCS

• Is the airway safe (use the recovery position)?

• Respiratory rate (< 8 breaths/min: over-sedation? > 20 breaths/min: developing pneumonia?)

• Pulse and blood pressure

• Oxygen saturations: maintain at > 90%

Any sudden change in behaviour is likely to have a cause – metabolic disturbance, pain, drug toxicity, or an acute event such as pneumonia or myocardial ischaemia.

Nursing Home Admissions

Dependence levels in patients who are admitted from a nursing home vary tremendously. One patient may have been bed-bound and totally dependent for all their needs for a number of years, whereas another from the same home may be mobile and dependent on nursing care only for specific areas of needs. The majority will be dependent for several basic functions, at least half will have cognitive impairment, and as many will have chronic urinary incontinence. The exact level of baseline dependence must be established from the home in every case. Particular care is needed in patients who have come to the nursing home within recent weeks – there may not have been time to identify any reversible causes of confusion or ill health. Their admission to the nursing home may have been triggered by an unrecognised but reversible physical illness.

Common problems in this group of patients are:

• falls

• dehydration during acute illness

• pressure sores and contractures

• delirium

• incontinence

• hearing problems

• sight problems

• depression

• dementia

During influenza outbreaks, many nursing home residents are admitted with cardiac failure, increasing breathlessness, wheeze and toxic confusion caused by pneumonia.

It cannot be assumed that every admission from a nursing home is for terminal care (→Case Studies 9.8). However, one of the current features of nursing home care is that frail patients are seen out of hours by on-call deputising medical services and admitted to hospital. There may be pressure from relatives that ‘something must be done’, equally there may be dismay that a seemingly natural progression towards death is punctuated by an unnecessary trip to an unfamiliar noisy ward in the middle of the night. It is critical to speak to the relatives immediately when the patient is admitted.

• What is the level of dependence?

• What is the time course of the deterioration?

• What are their expectations of the outcome?

• Have they any particular concerns or worries (this often involves uncontrolled pain/seeing their relative suffer)?

• Have they an opinion on what the patient may want?

• Has the patient been discharged from hospital recently?

Case Studies 9.8

CASE 1

An 85-year-old woman was admitted from a nursing home. She had been mobile with a walking frame, but had a 3-day history of increasing breathlessness. She remained very distressed and it was impossible to differentiate between bronchopneumonia and LVF. She was treated with oxygen, a combination of antibiotics, frusemide and low-dose opiates, on which she settled. She recovered fully.

CASE 2

An 81-year-old woman was admitted from a nursing home. She had been to the pain clinic within the previous 3 months because of unremitting backache and been started on fentanyl patches. She had become progressively dependent, and 1 month before admission had been transferred from a rest home into a nursing home, where she had continued to deteriorate and had taken to her bed.

On examination she had a GCS of 15, was lying rigidly in bed continually moaning, yet denying on direct questioning any discomfort or pain. Assessment was very difficult: there was no evidence of drug side-effects despite the fentanyl, and she appeared to have adequate levels of pain relief. She was screened for sepsis, the nursing home was contacted to make absolutely sure there were no other drugs that may have given a Parkinson’s disease-type of side-effect, and her fentanyl was reduced slightly in case this was an opiate-induced state.

None of this made any difference, but a rectal examination 24h after admission revealed severe faecal impaction. She was treated with Microlax® enemas and stool softeners with a good result and appeared less distressed. Nonetheless, she remained very dependent and was eventually transferred back to the nursing home.

It is far better to treat a patient aggressively in the early stages, particularly while the normal level of functioning or degree of reversibility is unclear.

Ethical Issues and the Elderly Sick

This is a very difficult area, in which even the most experienced medical and nursing staff can be left feeling very uncertain as to whether the correct decisions have been made. The fundamental issue for the individual patient is how far to pursue medical and supportive treatment or, having started them, whether they can be withdrawn:

• Cardiopulmonary resuscitation?

• Ventilatory or renal support?

• Surgery?

• Antibiotics?

• Artificial nutrition?

• Fluids?

Who should decide?

Most of these very difficult issues can be resolved with effective sharing of information between the health professionals and the family (→Box 9.2). This can be particularly important within the first 48h of admission, when the medical condition can change rapidly. It can be very helpful to contact the family, or to have them on the ward, at the times that key assessments are completed:

• soon after admission

• after the registrar’s ward round

• after the consultant’s round

Box 9.2

• What is the diagnosis and what is the prognosis?

• What are the goals of management?

— simple prolongation of life (e.g. nutritional support in irreversible coma)

— maintaining or improving function (e.g. successful defibrillation)

— providing comfort (e.g. subcutaneous morphine in advanced cancer pain)

• What are the prospects for reaching these goals with and without treatment?

• What is the burden associated with treatment?

— discomfort and side-effects (e.g. trauma of intubation and ventilation)

— survival with severe disability (e.g. post-arrest anoxic brain damage)

— what are the alternative treatments (e.g. oxygen and physiotherapy but not ventilation)?

Withholding versus withdrawing treatment?

Like many difficult issues on the ward, the key is to keep open the best possible lines of communication between the medical and nursing staff, the relatives and, most importantly, the patient.

The Emergency Admission of Patients With a Terminal Disease

Ninety percent of patients with advanced malignancy spend most of their last year at home and the majority would like to die there. In fact only 25% will die at home – many are admitted as emergencies prior to death because there is a change in their condition (often uncontrolled pain, increased confusion or a diminished level of consciousness) or because exhausted carers can no longer cope. The situation requires the utmost sensitivity and nursing skill:

• No-one is likely to know the patient’s case: the carers will be keenly aware of this.

• The patient will be on a complex regime, probably including a carefully tailored analgesic regime.

• The usual EAU approach: urgent tests, empirical antibiotics and IV fluids, may be entirely inappropriate in the setting of a patient at the (predicted) end of their life.

• The relatives and the patient may have unrealistic expectations of a same or next-day discharge back home. Given the usual circumstances of such admissions a finite time is usually required to maximise the drug regime, fine tune the care packages and marshal the appropriate resources in the community.

It is critically important to bring in the ‘home team’ who know the patient and their family and also to urgently involve the Hospital Palliative Care Service.

End of life nausea and vomiting: Levomepromazine (Nozinan®) is invaluable for symptom control in the terminally ill. It is a potent anti-emetic, one subcutaneous dose (6.25mg) can be effective for hours and it can be given as a subcutaneous infusion (12.5 to 25mg per 24 hours). Its sedative effect calms terminal agitation and restlessness.

Terminal breathlessness, restlessness and excessive airway secretions: Excessive airway secretions can be controlled with hyoscine hydrobromide, 400 mcg subcutaneously followed by a subcutaneous infusion of 1.2mg per 24 hours. Breathlessness responds to subcutaneous midazolam 2.5–5mg followed by 10–20mg per 24 hours as a subcutaneous infusion. Alternatives, with a less sedating effect, are hyoscine butylbromide (20mg subcutaneously stat and 60mg per 24 hour infusion) and haloperidol (2.5mg subcutaneous stat and 5mg per 24 hours).

These regimes need review adjustment to ensure patients remain symptom free yet at an appropriate level of sedation – relatives will often express concerns if the level of symptom control becomes inadequate (commonly this occurs during the night). This can become the major issue in the last hours of a patient’s life.

Further Reading

Falls

Downton, J.H., Falls in the elderly. (1993) Edward Arnold, London .

Oliver, D.; Britton, M.; Steel, P.; et al., Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool to predict which elderly patients will fall, British Medical Journal 315 (1997) 1049–1053.

Shaw, F.E.; Kenny, R.A., The overlap between syncope and falls in the elderly, Postgraduate Medical Journal 73 (1997) 635–639.

Tinetti, M.E., Preventing falls in elderly persons, New England Journal of Medicine 348 (2003) 42–49.

Delirium

Brown, T.M.; Boyle, M.F., Delirium: clinical review, British Medical Journal 325 (2002) 644–647.

Lacko, L.; Bryan, L.; Dellasega, C.; et al., Changing clinical practice through research: the case of delirium, Clinical Nursing Research 8 (3) (1999) 235–250.