CHAPTER 8 The SMAS facelift – restoring facial shape in facelifting

Introduction

The works of Skoog, Mitz and Peyronie enlightened plastic surgeons to the possibility of repositioning descended facial fat to the anatomic position of youth, providing an alternative to skin envelope tightening to enhance contour in the aging face. The recognition that sub-SMAS dissection offered a technical solution for facial rejuvenation spawned multiple anatomic studies to delineate an accurate understanding of facial soft tissue anatomy. This led to further investigations which more clearly defined both the anatomic and morphologic changes which occur in the aging face, leading to a plethora of technical approaches for facial rejuvenation. In reviewing the literature, good results can be seen utilizing what appears to be very different technical approaches. In reality, most of these seemingly different technical procedures share a common theme that contour restoration is predominantly through the re-elevation of facial fat as opposed to skin envelope tightening. While good results are possible through a variety of techniques, in my opinion, all methods have advantages, disadvantages and limitations, with the ultimate result often dependent upon underlying skeletal support and the quality of facial soft tissues for a particular patient. From my perspective, the key to consistent results in facelifting is not the particular technique utilized, but rather the preoperative aesthetic analysis and how the operative plan is individualized according to the aesthetic needs of the patient.

Physical evaluation – patient planning

• Skin quality and elasticity.

• Subcutaneous fat accumulation.

• Contour change developing from attenuation of deep layer support, i.e. jowling, deep nasolabial fold; and platysma banding with cervical obliquity.

• Degree of skeletal support – malar prominence, mandibular ramus height and length of mandibular body.

• The relationship between malar convexity and submalar concavity.

Anatomic considerations

1. Although there is variation in the thickness of the various layers from patient to patient, structures within each layer are anatomically constant. On a two-dimensional basis, the facial nerve exhibits a variety of branching patterns, but on a three-dimensional basis, the facial nerve always lies within a specific anatomic plane. This anatomic arrangement allows the surgeon to perform extensive sub-SMAS dissection safely, as long as the dissection proceeds at a level superficial to the plane of the facial nerve.

2. There is significant variability in terms of the thickness of the superficial fascial layer (SMAS). This variability of SMAS thickness is obvious from patient to patient. Also, the thickness of the SMAS will vary from one region of the face to another. Overlying the parotid gland, within the temporal region (temporoparietal fascia) and within the scalp (galea), the superficial fascia (SMAS) represents a substantial, discrete layer. As the superficial fascia is traced anteriorly in the face, overlying the masseter, buccal fat pad, and into the malar region, the SMAS tends to become thinner and less substantial. To elevate the superficial fascia in these areas requires precise dissection, so that the flap is thick enough to be useful in facial contouring.

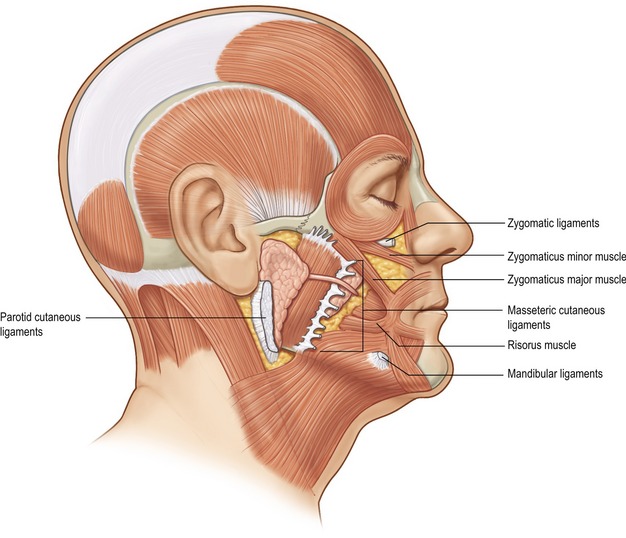

3. The muscles of facial expression are arranged in four anatomic layers which overlap one another. The muscles that are encountered in facelifting, including the platysma, orbicularis oculi, zygomaticus major and minor, and risorius muscle, are all superficially situated mimetic muscles. This is in contrast to deeply situated mimetic muscles such as the buccinator and mentalis muscle. Most of the muscles of facial expression lie superficial to the plane of the facial nerve. Because these muscles are superficial to the plane of the facial nerve, they receive their innervation along their deep surfaces. The only muscles within the facial soft tissue architecture that lie deep to the plane of the facial nerve are the mentalis, buccinator, and levator anguli oris muscles. Because these muscles lie deep to the plane of facial nerve, they receive their innervation along their superficial surfaces.

4. The muscles of facial expression, which are situated superficially within the facial soft tissue architecture and are involved with the movement of facial skin, are invested by the superficial fascia, which lines both the superficial and deep surfaces of these muscles. Because these muscles are invested by superficial fascia, this SMAS-mimetic muscle complex forms a single anatomic and functional unit whose components work together to move facial skin during animation.

5. Deep to the SMAS-mimetic muscle complex lies the deep facial fascia. The deep facial fascia represents a continuation of the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia cephalad into the face. Where this fascial layer is identified, it is given specific nomenclature. Overlying the parotid gland, the deep fascia is termed “parotid fascia” or “parotid capsule”; overlying the masseter muscle, it is termed “masseteric fascia”; and in the temporal region, it has been termed “deep temporal fascia.” The significance of the deep facial fascia is that all the facial nerve branches within the cheek lie deep to the deep facial fascia. Typically, these nerve branches course deep to the deep fascia until they reach the muscles of facial expression that they innervate, at which point they penetrate the deep fascia to innervate these mimetic muscles along their deep surfaces (Fig. 8.1).

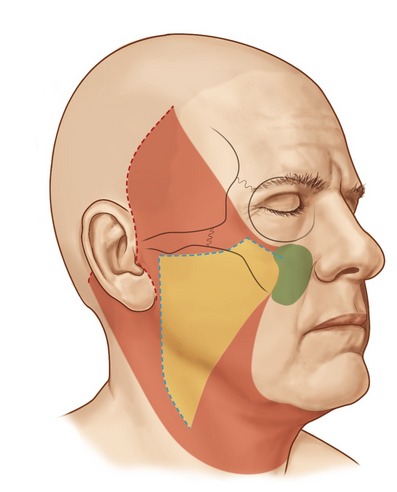

In an overview of the architectural arrangement of the facial soft tissue, the essential point to grasp is that there is a superficial component of the facial soft tissue that is defined by the superficial facial fascia and includes the SMAS and those anatomic components that move facial skin (including superficially situated mimetic muscle invested by SMAS, the subcutaneous fat, and skin). This is in contrast to the deeper component of the facial soft tissue, which is defined by the deep facial fascia and those structures related to the deep fascia (including the relatively fixed structures of the face, such as the parotid gland, masseter muscle, periosteum of the facial bones, and facial nerve branches) (Fig. 8.2). As the human face ages, many of the stigmata that are typically seen in aging relate to a change in the anatomic relationship that occurs between the superficial and deep facial fascia.

Extended SMAS technique

In skin flap dissection, it is important to develop uniform skin flaps during the subcutaneous undermining, with care to leave some fat intact along the superficial surface of the SMAS. If the skin flaps are dissected such that no fat is left along the superficial surface of the SMAS, then the SMAS becomes more difficult to raise, appearing thin, tenuous and prone to tearing. Much of the contouring that I obtain in my facelift has to do with elevation and fixation of the SMAS layer. The more substantial the SMAS flap, often the better long-term results that can be obtained in terms of facial contouring. Transillumination when performing subcutaneous dissection is a useful technique in allowing precise skin flap elevation.

SMAS elevation

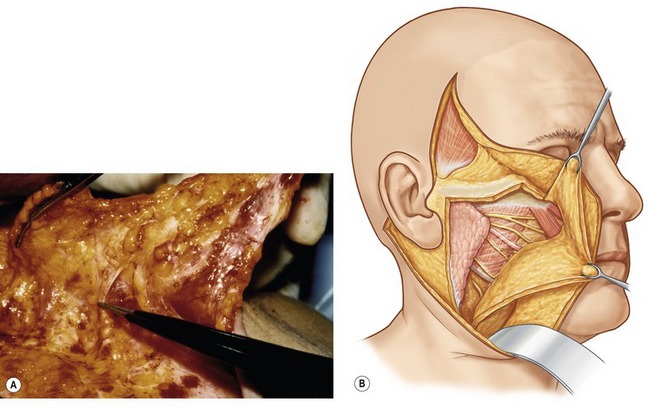

The dissection of the superficial fascia allows the surgeon to re-elevate jowl and descended malar fat back upward into the face toward their previous normal anatomic location. In patients with prominent nasolabial folds, and significant malar pad descent, it has been my feeling that the SMAS dissection should extend into the malar region in an effort to re-elevate the malar fat pad back upward overlying the zygomatic eminence. An added benefit of performing a more extensive anterior dissection of the SMAS is that it frees this layer from the restraint of both the zygomatic and masseteric ligaments, and this anterior release provides for a more complete elevation of the facial fat below the oral commissure and along the anterior portion of the jowl.

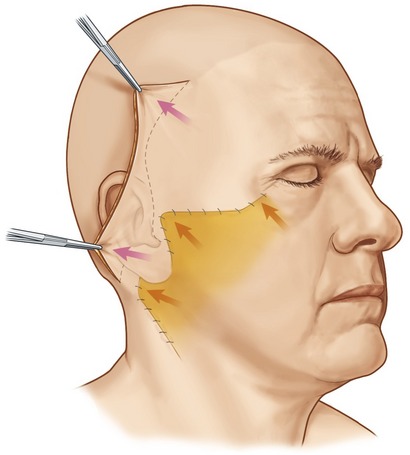

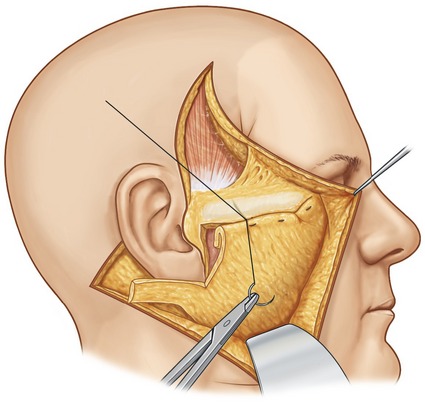

The incisions for extended SMAS dissection begin approximately 1 cm inferior to the zygomatic arch to ensure frontal branch preservation (Fig. 8.3). This horizontal incision is continued several centimeters forward to the region where the zygomatic arch joins the body of the zygoma. At this point, the malar extension of the SMAS dissection begins with the incision angling superiorly over the malar eminence toward the lateral canthus for a distance of 3 to 4 cm. On reaching the edge of the subcutaneous skin flap in the region of the lateral orbit, the incision is carried inferiorly at a 90 degree angle toward the superior aspect of the nasolabial fold. A vertical incision is designed along the preauricular region, extending along the posterior border of the platysma to a point 5 to 6 cm below the mandibular border. In essence, the malar extension of the SMAS dissection simply represents an extension of a standard SMAS dissection into the malar region in an attempt to obtain a more complete form of deep layer support.

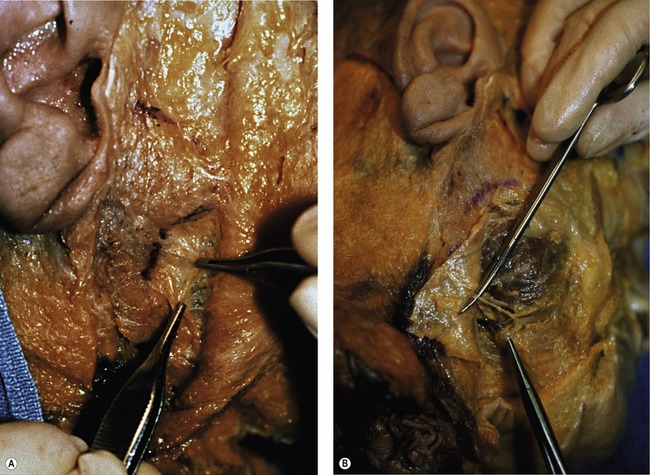

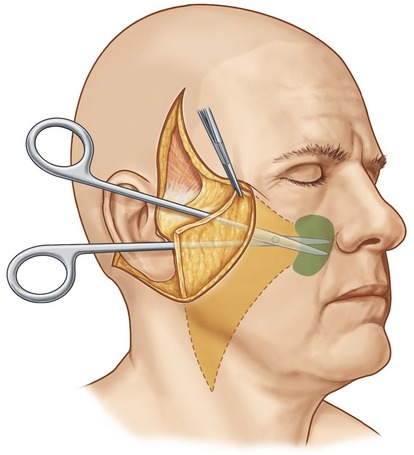

The SMAS in the malar region is then elevated in continuity with the SMAS of the cheek. When elevating this flap, the fibers of the orbicularis oculi, as well as the zygomaticus major and minor, are usually evident and the flap is elevated directly along the superficial surface of these muscles. It is important to carry the dissection directly external to these muscle fibers, where a natural plane exists, remembering that the facial nerve branches lie deep to these muscular bellies. The malar SMAS is then elevated until the flap is freed from the underlying zygomatic prominence. Freeing of the SMAS completely from the zygomatic attachments is an important technical point in obtaining the mobility necessary to reposition the malar soft tissue superiorly. To obtain this mobility usually also requires a division of the upper fibers of the masseteric cutaneous ligaments, which will expose the underlying body of the buccal fat pad. The cheek portion of the SMAS dissection is performed beginning directly overlying the parotid gland and then extending this dissection anterior to the parotid utilizing a combination of sharp and blunt dissection toward the anterior border of the masseter (Fig. 8.4).

In most patients, following extended SMAS dissection of the cheek and malar regions, mobility of the soft tissues lying lateral to the nasolabial fold remains restricted unless the dissection is carried more medially. This restriction in movement results from the undivided retaining ligaments which originate medial to the zygomaticus minor. To improve mobility, I commonly continue malar pad elevation medially in an area where we have not subcutaneously undermined the skin. This dissection is carried directly in the plane between the malar fat and the superficial surface of the elevators of the upper lip. It is usually quite easy to delineate this level of dissection after the malar SMAS elevation is complete, and the superficial surface of the elevators of the upper lip is visualized. The scissors are then inserted directly superficial to the elevators of the upper lip, and blunt dissection is quickly performed by pushing the scissors in a series of passes bluntly toward the nasolabial fold. We find that when we insert the scissors in the proper plane, the dissection quickly glides through the malar soft tissues and we usually will feel a “snap” as we dissect through the remaining retaining ligaments. Once these structures are divided, one notes greater mobility when traction is applied to the malar portion of the SMAS flap, translating into greater movement along the uppermost portion of the nasolabial fold (Fig. 8.5).

Fig. 8.5 It is commonly necessary to extend the malar SMAS dissection more peripherally than the subcutaneous dissection to obtain adequate flap mobility of the soft tissues lateral to the nasolabial fold. This portion of the dissection is easily performed by simply inserting the scissors in the plane between the superficial surface of the elevators of the upper lip and the overlying subcutaneous fat. Once the scissors are inserted in the proper plane, the surgeon bluntly dissects in a series of passes past the nasolabial fold (area marked in green). As long as the scissors remain superficial to the elevators of the upper lip, motor nerve injury will be prevented. Two or three passes are usually required to obtain adequate flap mobility.

From Baker TJ, Gordon HL, Stuzin JM. Surgical rejuvenation of the face, 2nd edn. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1996, p. 257.

Repositioning and closure of the SMAS is then performed. The malar SMAS flap is advanced superiolaterally over the zygomatic prominence in a direction perpendicular to the nasolabial fold, and usually paralleling the zygomaticus major muscle. After superior and lateral advancement, if a malar augmentation is not planned, the excess tissue can be excised and the flap securely fixated to the zygomatic periosteum with interrupted sutures. In many patients, I incorporate Vicryl mesh (an absorbable mesh) into the SMAS fixation to improve the tensile strength of SMAS closure (Figs 8.6, 8.7).

Fig. 8.7 Diagram illustrating how the excess SMAS, rather than being excised, is rolled onto itself (forming a double layer of SMAS thickness). Once the roll has been formed, it is fixated to the periosteum of the zygomatic buttress using permanent sutures. It is important to obtain a secure intraoperative fixation, and emphasize that fixation is as important as adequate SMAS mobilization. A small piece of Vicryl mesh is typically incorporated into the roll of the SMAS to improve its tensile strength.

From Baker TJ, Gordon HL, Stuzin JM. Surgical rejuvenation of the face, 2nd edn. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1996, p. 263.

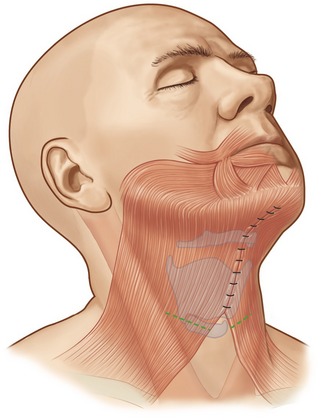

If significant platysma banding is present, a platysmaplasty is performed through a submental incision. I typically approximate the medial edges of the platysma extending from the mentum caudally toward the base of the neck, followed by a transverse platysma myotomy performed low in the neck to alleviate tension along the platysma closure (Figs 8.8–8.12).

Fig. 8.9 A, Preoperative appearance of a 59-year-old male following a 90 pound weight loss from a gastric bypass procedure. Notice the significant areas of facial deflation along the infraorbital rim, lateral orbital rim and malar region. Also notice the radial expansion of skin and fat lateral to the nasolabial fold, most marked on the right side. Not only does malar fat descend, but attenuation of the retinacular connections among skin, fat and deep facial fascia lateral to the nasolabial line allows prolapse of soft tissue, which accentuates nasolabial prominence. B, Postoperatively, the areas of deflation along the infraorbital rim, lateral orbital rim, and malar region are improved as facial fat has been repositioned into these regions. The nasolabial folds are somewhat improved after malar pad repositioning, but correction is incomplete, especially on the right. Malar pad elevation helps to flatten the prominent nasolabial fold, but does little to correct radial expansion, with the skin lateral to the nasolabial line remaining prolapsed from its attachments to the facial skeleton.

From Stuzin JM. Restoring facial shape in facelifting: The role of skeletal support in facial analysis and midface soft-tissue repositioning. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119:362–376.

Fig. 8.11 A, Preoperative appearance. Note that facial shape is oval, secondary to malar deflation, associated with an increase in submalar fullness. B, Postoperatively, following malar pad elevation, malar volume is enhanced in association with a restoration of submalar concavity, producing a more angular appearance to facial shape.

Postoperative care

The following postoperative recommendations have proven helpful for most patients:

• Pressure dressings are not used. A light facelift dressing is placed for the first 24 hours.

• The head of the bed is elevated at all times, but flexion of the patient’s neck is avoided because this may compromise circulation to the cervical flap.

• Appropriate pain and sleep medications are given; strong narcotics are rarely required.

• The patient may go to the bathroom with assistance on the first postoperative day and as desired thereafter.

• The first dressing is changed after 24 hours. At this time, the wounds are inspected and no further dressing is utilized.

• Preauricular sutures are removed on the fifth or sixth postoperative day.

• All sutures are removed by the tenth postoperative day.

• Antibiotics are routinely used preoperatively and for 5 days postoperatively. My current preference is Levaquin, 500 mg once daily, begun the night prior to surgery.

• If crusty or oozing, wounds are cleaned with hydrogen peroxide and coated with a topical antibiotic ointment.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Improving technical control through contouring the superficial facial fascia and platysma provides for a more consistent, aesthetically pleasing result which is natural in appearance.

• Patient selection is probably the most critical factor when determining the success of a proposed aesthetic procedure.

• Although aging represents a complex process, many of the stigmata developing in the aging face involve a change in the relationship between the superficial and deep facial fascia, with the superficial unit of the facial soft tissue descending inferiorly in relation to the fixed deeper structures of the face.

• The prime advantage of performing skin undermining separately from SMAS dissection is that it allows these two layers to be redraped along vectors which are independent of one another.

• The importance of incision quality cannot be overemphasized in diminishing the stigmata that the patient has undergone a surgical procedure.

Pitfalls

• Imprecise subcutaneous undermining of the skin flap can lead to a paucity of fat being left along the superficial surface of the SMAS, making it difficult or impossible to raise the SMAS as a discrete anatomic layer, limiting its usefulness in facial contouring.

• Not extending the release of the SMAS anterior to the adherence of the retaining ligaments limits the movement of this layer, thereby limiting surgical control in terms of restoring facial shape.

• Vertical skin tension to tighten the face often produces an unnatural surgical appearance to the postoperative result and can be avoided by utilizing the superficial fascia to vertically reposition facial fat.

• Imprecise incision design and skin flap inset can lead to noticeable scars, hairline shifts, tragal and earlobe distortion. Limiting skin tension by utilizing the SMAS to restore facial shape provides the surgeon with greater control in terms of scar perceptibility.

• Attempting to improve cervical contour through lateral platysma tension and closed suction lipoplasty of the neck provides less consistent results than approaching platysmaplasty anteriorly through a submental incision.

Summary of steps for extended SMAS procedure

1. Tragal margin incision design which respects the aesthetic units of the tragus and preserves the tragal insisura.

2. The use of transillumination to allow precise skin flap undermining which preserves the fat along the superficial surface of the SMAS provides greater consistency in SMAS flap elevation.

3. Limiting subcutaneous undermining over the buccal recess and buccinator allows this region of the cheek to be repositioned through SMAS rotation producing greater control in terms of submalar contour and jowl correction.

4. The incision of the extended SMAS dissection parallels the zygomatic arch and then extends superiorly over the malar eminence in the area where the arch joins the body of the zygoma.

5. Releasing the SMAS from the restraints of the retaining ligaments until the SMAS moves freely requires the surgeon to carry the dissection into the mobile region of the SMAS which lies anterior to the retaining ligaments over the malar eminence and parotid.

6. Vectoring the SMAS should be patient-specific and should be determined preoperatively with the patient in an upright position. Variation in vectors between the right and left side of the face are common.

7. Secure fixation of the SMAS, often incorporating Vicryl mesh into the closure improves consistency in shaping and postoperative results.

8. Approaching platysmaplasty through a submental incision and suturing the platysma from the mentum to the base of the neck provides greater control in cervical contouring.

9. Meticulous hemostasis leads to a low hematoma rate and more rapid postoperative recovery.

10. Placement of drains along the base of the neck prior to closure promotes rapid postoperative recovery.

11. Precise skin flap inset and closure with minimal tension, especially along the tragus and earlobe leads to control of scar perceptibility.

Baker TJ, Gordon HL, Stuzin JM. Surgical rejuvenation of the face, 2nd edn. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996.

Bames H. Truth and fallacies of face peeling and facelifting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1927;126:86.

Barton FE, Jr. Rhytidectomy and the nasolabial fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:601.

Connell BF. Neck contour deformities: The art, engineering, anatomic diagnosis, architectural planning, and aesthetics of surgical correction. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:683.

Feldman JJ. Corset platysmaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:333.

Furnas D. The retaining ligaments of the cheek. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:11.

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:80.

Owsley JQ, Jr. Lifting the malar fat pad for correction of prominent nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:463.

Skoog T. Plastic surgery – New methods and refinements. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1974.

Stuzin JM. Restoring facial shape in facelifting: The role of skeletal support in facial analysis and midface soft-tissue repositioning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:362.

Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Baker TM. Refinements in facelifting: Enhanced facial contour using Vicryl mesh incorporated into SMAS fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:290.

Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL, Baker TM. Extended SMAS dissection as an approach to midface rejuvenation. Clin Plast Surg. 1995;22:295–311. –

Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL. The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: Relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:441.