16 The small and large intestine

Surgical anatomy and physiology

Anatomy and function of the small intestine

Summary Box 16.1 Clinical assessment of a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms

• Gastrointestinal symptoms are very common

• Most symptoms are due to self-resolving illness

• Patient age is an important factor when considering the differential diagnoses

• Duration of symptoms is an important arbiter of the need for investigation

• Careful assessment of the nature and severity of symptoms is important and may indicate peritonitis, obstruction or severe inflammation

• Symptoms of self-resolving intestinal disorders that are managed conservatively are often indistinguishable from major problems

• Investigation usually involves endoscopy and imaging, as well as stool culture.

strong submucosa and comprises a single layer of columnar cells in a villiform structure that dramatically increases the absorptive surface area. Columnar glandular epithelium is interspersed with mucus-secreting cells, Paneth cells and amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) cells derived from the neural crest. Between the inner layer of circular muscle and the outer longitudinal layer runs Auerbach’s myenteric plexus, which comprises vagal parasympathetic fibres and sympathetic fibres from the lesser and greater splanchnic nerves. This plexus controls orderly propulsive contractions of the muscular layers of the gut wall. The sympathetic nervous system mediates the sensation of visceral pain, and a submucosal plexus (Meissner’s plexus) of autonomic nerves innervates the glandular cells in the epithelium.

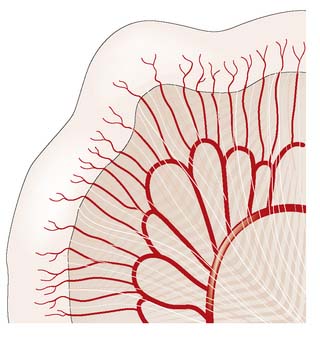

The small intestine is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery, which runs in the root of the small bowel mesentery, supplying the bowel by a series of arterial arcades (Fig. 16.1). These midgut vessels communicate with the coeliac axis through the pancreaticoduodenal arcade. The superior mesenteric supply also communicates with that of the inferior mesenteric artery by contributing to the colonic marginal artery through the left branch of the middle colic artery, which joins to the ascending branch of the left colic artery. Venous blood drains via the superior mesenteric vein to the portal vein. Lymphoid aggregates in the submucosa (Peyer’s patches) are more numerous in the ileum, and lymph drains to regional nodes in the root of the mesentery before passing to the cisterna chyli.

Anatomy and function of the large intestine and appendix

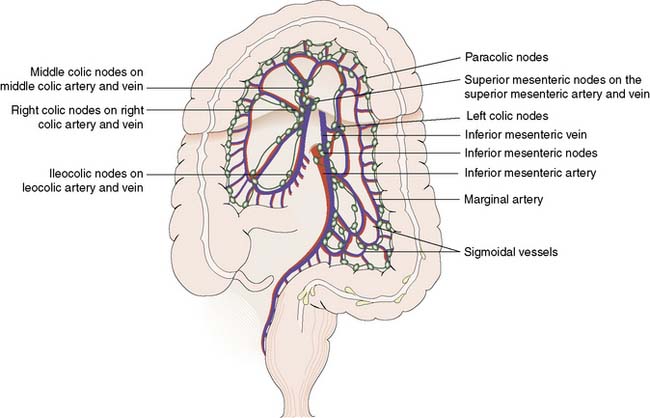

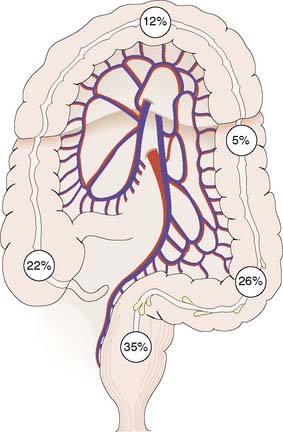

The inferior and superior mesenteric arteries supply the colon and anastomose via a marginal artery (Fig. 16.2) that allows collateral supply in the event of arterial occlusion, but at the splenic flexure this arterial communication may be tenuous. The superior rectal artery is the continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery, supplying the rectum and anastomosing with the middle and inferior rectal arteries (branches of the internal iliac arteries). The inferior mesenteric vein drains into the splenic vein. Lymph channels run along the course of the arterial supply, draining to epicolic and paracolic nodes close to the bowel wall, and to regional nodes at the origin of the superior and inferior mesenteric vessels (Fig. 16.2). Lymph from the rectum drains upwards to superior rectal and inferior mesenteric nodes, whereas anal canal lymph drains to inguinal nodes. Knowledge of the lymphatic drainage has considerable relevance to surgical lymphadenectomy performed as part of radical cancer clearance, as well as to radiotherapy for rectal and anal cancers.

Clinical assessment of the small and large intestine

Disorders of the appendix

Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis remains the most common acute abdominal emergency in childhood, adolescence and early adult life and is discussed in Chapter 12.

Appendiceal tumours

Adenocarcinoma of appendix

Summary Box 16.2 Tumours of the appendix

• Around 85% of all appendiceal tumours are carcinoids, the appendix being the most common site of carcinoid tumour in the gastrointestinal tract

• Carcinoid tumours are found in 0.5% of surgically removed appendices

• Size > 2 cm indicates increased risk of malignancy, but lymph node involvement is rare and metastases are extremely rare

• Appendix adenocarcinoma is rare and may be associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)

• Mucin-secreting cystadenoma, if ruptured, may lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei

• Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a rare, capricious condition that causes pressure symptoms on intestine and other intra-abdominal organs, and for which there is no curative therapy.

Inflammatory bowel disease

In view of the similarities in clinical presentation and in some aspects of management, it is useful to discuss Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis together (Table 16.1). Ulcerative colitis affects the colon and rectum exclusively, whereas Crohn’s disease may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammation is restricted to the mucosa in ulcerative colitis but transmural inflammation is a hallmark of Crohn’s disease. There are also important implications for prognosis, as surgery for ulcerative colitis is curative, whereas Crohn’s disease frequently follows a relapsing course, despite medical or surgical intervention.

Table 16.1 Clinical features of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 5–7 per 100 000 and rising | 10 per 100 000 and static |

| Extent | May involve entire gastrointestinal tract | Limited to large bowel |

| Rectal involvement | Variable | Almost invariable |

| Disease continuity | Discontinuous (skip lesions) | Continuous |

| Depth of inflammation | Transmural | Mucosal |

| Macroscopic appearance of mucosa | Cobblestone, discrete deep ulcers and fissures | Multiple small ulcers, pseudopolyps |

| Histological features | Transmural inflammation, granulomas (50%) | Crypt abscesses, submocosal chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt architectural distortion, goblet cell depletion, no granulomas |

| Presence of perianal disease | 75% of cases with large bowel disease; 25% of cases with small bowel disease | 25% of cases |

| Frequency of fistula | 10–20% of cases | Uncommon |

| Colorectal cancer risk | Elevated risk (relative risk = 2.5) in colonic disease | 25% risk over 30 years for pancolitis |

| Relationship with smoking | Increased risk, greater disease severity, increased risk of relapse and need for surgery | Protective, first attack may be preceded by smoking cessation within 6 months |

Crohn’s disease

Pathology

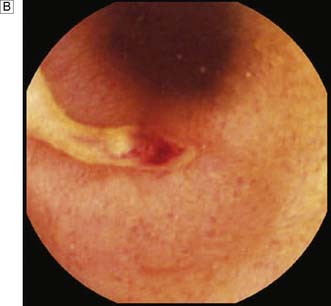

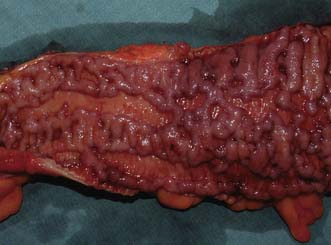

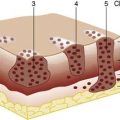

Macroscopically, Crohn’s disease produces a cobblestone appearance, in which oedematous islands of mucosa are separated by crevices or fissures; these can extend through all coats of the bowel wall. Serpiginous ulceration is common so that fibrosis may result in multiple strictures of varying length. Multiple areas of inflammation are common with intervening normal bowel (skip lesions, Fig. 16.3). Full-thickness involvement of the bowel wall leads to serosal inflammation, adhesion to neighbouring structures, and sinus or fistula formation. Microscopically, there are deep fissuring ulcers, oedema and inflammatory cell infiltrates with foci of lymphocytes and non-caseating granulomas in 50% of cases.

Clinical features

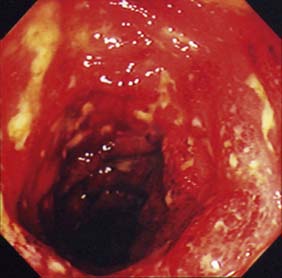

Examination may reveal malnutrition and there may be a palpable abdominal mass. There may be features of subacute intestinal obstruction, and this may be due to active disease, stricturing of ‘burnt-out’ disease, or adhesions from previous surgical intervention. Fistula formation occurs in 20% of patients with small and large bowel disease, but less in those with disease restricted to the large bowel. Fistulae may communicate with adjacent loops of bowel, other viscera (e.g. bladder, vagina) or the skin. External fistulae may result from surgical intervention and commonly involve the anterior abdominal wall or perineum (Fig. 16.4). Abscesses can result from chronic bowel perforation, but free perforation is relatively uncommon because the inflamed segment usually adheres to surrounding structures. Although less common than in ulcerative colitis, toxic dilatation can complicate colonic disease. Fulminant Crohn’s colitis is shown in Figure 16.5; deep ulcers and fibrosis with mucosal oedema and inflammation can be seen.

Investigations

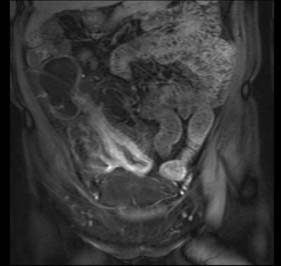

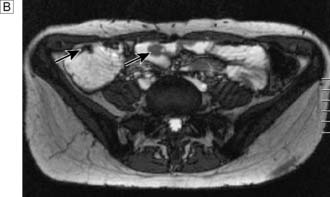

Assessment of nutritional status, including serial weight measurement, is essential. Anaemia may be due to: iron deficiency from chronic blood loss and rarely due to malabsorption; a normocytic anaemia of chronic disease; macrocytic anaemia from vitamin B12 or folate malabsorption. Elevated acute-phase proteins such as C-reactive protein are useful in monitoring disease, though not specific for diagnostic purposes. Until recently, the diagnosis was most frequently made on barium follow-through: typical features are shown in Figure 16.6 – rose-thorn ulcers, long irregular terminal ileal stricture at the site of previous ileocaecal resection. Active disease produces radiological evidence of thickening, luminal narrowing and separation of loops, and is often associated with mucosal ulceration, deep fissuring ulcers and cobblestone appearance. Skip lesions and fistula formation may be apparent. However, MRI enteroclysis (image enhanced by administering oral osmotically active agent – e.g. PEG) has progressively become the investigation of choice (Fig. 16.7), which also has the advantage of limiting radiation exposure. Rectal examination, proctoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy determine disease extent and biopsy of inflamed bowel is mandatory. Newer investigative techniques include video-capsule endoscopy (Fig. 16.8), enteroscopy, and CT colonography. Double-contrast barium enema still has a place for assessing disease extent and delineation of fistulae.

Management

Surgical management

1. Onset of complications of luminal disease: fulminant colitis, life-threatening haemorrhage, obstruction, abscess/sepsis, perforation, fistulation.

2. Acute or chronic failure of medical management to control symptoms/disease activity, failure to thrive, complications of medical therapy.

3. Treatment or prophylaxis of malignancy.

4. Perianal disease: abscess, fistula, anorectal stricture (EBM 16.1).

16.1 Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP; IBD Section, British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2004 Sep;53 Suppl 5:V1-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1867788.

Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, Lucassen A, Jenkins P, Fairclough PD, Woodhouse CR; British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland. Gut. 2010 May;59(5):666-89. http://gut.bmj.com/content/59/5/666.long

Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or adenomas. NICE Guideline. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13415/53641/53641.pdf

Summary Box 16.3 Indications for surgery in Crohn’s disease

• Chronic subacute obstruction due to fibrotic strictures, adhesions or refractory disease

• Symptomatic disease unresponsive to, or poorly controlled by medical management

• Chronic relapsing disease on discontinuation of medical management and steroid dependency

• Complications of medical management (e.g. osteoporosis)

• Concerns about long-term immunosuppression, risk of malignancy and viral/atypical infections

• Onset of malignancy, including colorectal adenocarcinoma and small bowel lymphoma

• Rarely, control of debilitating extra-colonic manifestations such as iritis and sacroiliitis.

Ulcerative colitis

The annual incidence of ulcerative colitis is ∼︀10/100 000 population in Westernized countries but rare in developing countries. The aetiology is incompletely understood, but genetic, immunological and dietary factors all play a part. The disorder may affect any age group but peak incidence is in early adulthood. In the majority of cases, the disease is contiguous, affecting the rectum and extending proximally (see Table 16.1). In 5% of cases, it is segmental and the rectum is occasionally spared. There is substantial risk of colorectal adenocarcinoma in cases with pancolitis. Although ulcerative colitis is primarily a disease of the large bowel, systemic manifestations (iritis, polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, hepatitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum) can occur. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) affects 2–5% of cases of ulcerative colitis; it tends to indicate severe disease and predicts complications. Patients with PSC may develop liver failure and require liver transplantation.

Pathology

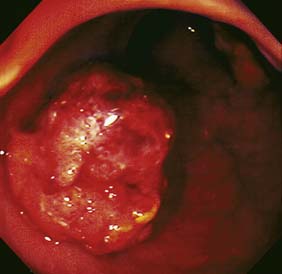

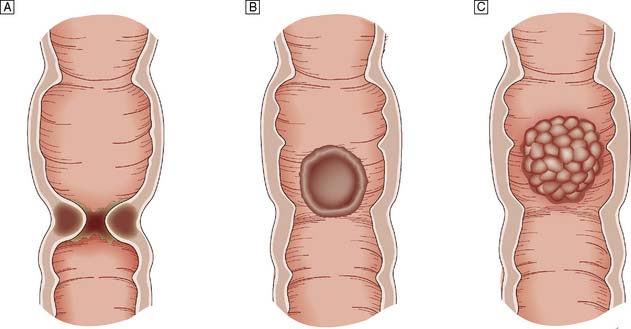

The characteristic feature of ulcerative colitis is inflammation restricted to the mucosa and submucosa of the large bowel. In severe episodes, there may be full-thickness involvement with inflammatory infiltrate. Abscesses develop at the base of the colonic crypts, which burst and coalesce to form crypt abscesses. These undermine the mucosa, resulting in ulceration (Fig. 16.9) and oedema of the intervening mucosa, which may form inflammatory pseudopolyps. Histologically, as well as ulceration and crypt abscesses, there is chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt architectural distortion and goblet cell depletion, but granulomas are absent. The colon loses its haustrations and becomes thick and rigid. Stricturing is uncommon and its presence should raise the possibility of Crohn’s disease. There can be difficulty in distinguishing ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s colitis both pathologically and clinically, when the term ‘indeterminate colitis’ is used to denote uncertainty. There may even be migration from one disease entity to the other. There are important implications for surgical treatment, since ileo-anal pouch should be avoided in cases of Crohn’s colitis.

Investigations

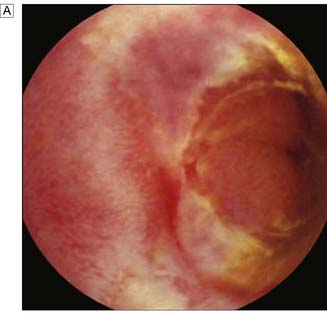

Expert colonoscopy is the mainstay of diagnosis and assessment of disease extent/severity. Endoscopic features of severe acute colitis are shown in Figure 16.10. Barium enema is infrequently used in modern inflammatory bowel disease practice and may risk perforation. Typical changes include loss of haustrations, fluffy granularity of the mucosa, and pseudopolyps. Undermining ulcers may create a double contour to the edge of the colon. Widening of the retrorectal space, due to perirectal inflammation and reduced distensibility of the rectum, is common. In longstanding colitis, the bowel may become short and featureless, resembling a smooth tube (lead-pipe colon). In an acute attack, plain films of the abdomen may reveal a dilated gas-filled colon in which pseudopolyps are evident. When toxic dilatation is suspected, daily plain X-rays are essential to monitor progress (Fig. 16.11). ‘Backwash ileitis’ may produce a dilated and featureless terminal ileum in which the mucosa appears granular. In the acute phase, it is essential to collect stool cultures to exclude supervening bacterial infection and especially C. difficile.

Management

Surgical management

Summary Box 16.4 Indications for surgery in ulcerative colitis

• Symptomatic disease unresponsive to, or poorly controlled by, medical management

• Chronic relapsing disease on discontinuation of medical management and steroid dependency

• Complications of medical management

• Concerns about long-term immunosuppression, risk of malignancy and viral/atypical infections

• Severe dysplasia on surveillance biopsies of colorectal epithelium

• Onset of colorectal adenocarcinoma

• Rarely, control of debilitating extra-colonic manifestations such as iritis and sacroiliitis.

Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis

Colorectal cancer risk in long-standing ulcerative colitis is a major factor contributing to surgical decision-making. Carcinoma is typically difficult to detect in colitis, is usually poorly differentiated and has a poor prognosis. Around 2% of all patients will develop cancer at 10 years, 8% at 20 years and 18% at 30 years. In pancolitis, the overall risk is around 25% after 30 years. Early age at first onset (< 15 years), pancolitis, a family history of colorectal cancer and associated PSC are strong cancer risk factors. Cancer surveillance is recommended in the long-term management of patients with chronic ulcerative colitis, and colonoscopy should be performed at 2-yearly intervals (see EBM 16.1). Random biopsies are taken at surveillance colonoscopy, since dysplasia indicates a high risk of cancer. Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) is a high-risk indicator of impending, or concurrent, cancer development. Cancer risk for patients with high-grade dysplasia or DALM is > 60% in the next 2 years and so restorative proctocolectomy is recommended. Patients with pancolitis may opt for prophylactic restorative proctocolectomy, especially when ulcerative colitis was diagnosed before the age of 15 years, rather than the uncertainty associated with life-long surveillance.

Disorders of the small intestine

Small bowel neoplasms

Small bowel tumours account for less than 5% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms.

Malignant tumours

Carcinoid tumour

The small bowel is the second most common site for carcinoid tumour (after appendix). Metastasis to lymph nodes is common at presentation, and obstruction and bleeding are the usual modes of presentation. Abdominal CT typically reveals a small bowel mass lesion with prominent calcification (Fig. 16.12). There may be features of the carcinoid syndrome in the presence of liver metastasis. Tests for urinary 5-HIAA (hydroxy-indole-acetic acid) and blood levels of chromogranin A should be undertaken. The primary tumour should be resected where possible. Lesions are frequently multifocal and may require multiple resections.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

Clinical features

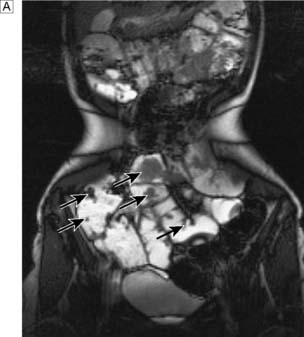

Most cases present in childhood or adolescence. There are usually dark brown or bluish spots on the lips and inside the mouth. The face, palms, soles, arms and perianal region can also be affected, but patients without pigmentation have been described. The usual presentation is with abdominal pain or obstruction due to intussusception of a polyp, but rectal bleeding and iron deficiency anaemia are also common. The diagnosis may be made in childhood or early adulthood on clinical grounds due to the association of abdominal colic and typical pigmentation. The small bowel investigation of choice in suspected Peutz–Jeghers Syndrome is MRI enteroclysis (Fig. 16.13). This avoids the radiation dose associated with repeated barium small bowel follow-through or CT examinations.

Jejunal diverticulosis

Jejunal diverticulae are acquired during adult life. Occasionally, only one or two diverticula are present but often diverticulosis is very extensive, with multiple wide-mouthed sacs caused by herniation of mucosa into the mesentery at the site of vessel penetration of the gut wall. Jejunal diverticulosis may be first diagnosed at laparotomy for complicated disease, or incidentally on imaging studies (Fig. 16.14). Diverticulae may cause bleeding, inflammation, malabsorption (due to bacterial over-colonization) and perforation. Occasionally, fish bones or NSAID tablets can become trapped in a diverticulum and cause local perforation. In symptomatic disease the extensive nature of the disorder often necessitates a conservative approach with antibiotics and intravenous fluids. However, a bowel segment with complicated diverticulosis may require limited resection, leaving other affected areas in situ.

Small and large bowel obstruction

Obstruction refers to a mechanical impedance to the normal propulsive action through the intestine. While the underlying mode of clinical presentation and underlying aetiology may differ between small and large intestine, a number of underlying principles can be considered together. The most common causes of small intestinal obstruction are adhesions (60%), obstructed hernia (20%) and malignancy (primary and secondary – 5–8%). In the large bowel, colorectal adenocarcinoma predominates (> 70%), followed by stricturing diverticular disease (10%) and sigmoid volvulus (5%). The aetiology of large and small bowel obstruction can be systematically classified as intraluminal, intramural and extramural (Table 16.2). Treatment should be focused on the underlying cause of obstruction and operation is frequently required.

| Small intestine | Large intestine | |

|---|---|---|

| Intramural (intrinsic) | Crohn’s disease Radiation stricture Tuberculosis Ischaemic stricture (caecal carcinoma) Primary tumour – lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumour Intussusception secondary to: hypertrophy of Peyer’s patches, Peutz–Jeghers polyp |

Colorectal adenocarcinoma Diverticular stricture Sigmoid volvulus Radiation stricture (rectum/sigmoid) Ischaemic stricture Caecal volvulus Crohn’s disease |

| Extrinsic | Postoperative adhesions Adhesions from previous inflammatory condition Congenital band Hernia Compression by tumour mass Volvulus |

Rare due to lumen diameter and retroperitoneal location Compression by tumour mass Massive inguinal hernia Incisional hernia |

| Intra-luminal | Foreign body Gallstone ileus Worm infestation Bezoar |

Faecal concretion (very rare) |

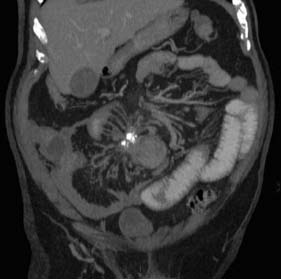

Full clinical history and examination is essential, along with immediate instigation of intravenous fluid and electrolyte therapy. Digital rectal examination may reveal rectal or extrinsic malignancy, empty rectum or constipation. Hernial orifices must be carefully inspected and any previous surgical abdominal scars noted. Abdominal X-ray will reveal distended small bowel or large bowel loops (Fig. 16.15) and may give an indication of the level of obstruction. Free gas under the diaphragm indicates perforation and mandates laparotomy and grossly distended bowel loops or evidence of a closed loop obstruction also merit early surgical intervention. Increasingly CT scan is used to assess bowel obstruction, because it allows interpretation of the likely need for surgery, as well as identifying the underlying aetiology (Fig. 16.16). Right iliac fossa tenderness along with radiological evidence of gross caecal distension in the presence of distal colonic obstruction is a critical sign as it indicates imminent caecal perforation, which is a frequent complication of distal colonic obstruction. The reason that the caecum perforates even with obstruction due to sigmoid cancer is because the caecum is anatomically the largest diameter segment in the gut. Thus tension is greatest in the caecal wall, despite equalized intra-luminal pressure along the colon (practical relevance of the Law of Laplace).

Fig. 16.16 CT of a large and small bowel obstruction proximal to a splenic flexure carcinoma (arrowed).

Pseudo-obstruction and nonmechanical gut functional disorder

Pseudo-obstruction

The causes of pseudo-obstruction are shown in Table 16.3. The underlying mechanism is not fully understood but the pathogenesis involves autonomic imbalance resulting from decreased parasympathetic tone or excessive sympathetic output. It is essential to consider pseudo-obstruction in patients who present with signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction.

Table 16.3 Causes of non-mechanical bowel dysfunction/pseudo-obstruction

| Systemic/metabolic |

Non-neoplastic disorders of the large intestine

Colonic diverticular disease

Colonic diverticulae may give rise to intermittent lower abdominal/left iliac fossa pain, altered bowel habit, urgency of defaecation and episodic rectal bleeding. The sigmoid colon may be tender on examination. Barium enema reveals muscle thickening and multiple diverticula (Fig. 16.17). Abdominal CT, either as CT colonography or plain abdominal CT, is used increasingly and provides an assessment of the degree of surrounding inflammation and/or abscess formation, in addition to extent of the diverticular changes (Fig. 16.18). Colonoscopy reveals the ostia of diverticulae and may show surrounding inflammation.

In the management of uncomplicated diverticular change, patients should be advised to take a high-fibre diet, supplemented by bran or a bulk laxative such as methylcellulose. Stimulant laxatives and purgatives are to be avoided. Antispasmodics, such as propantheline or mebeverine, may be useful if there is smooth muscle spasm and colicky pain. There is evidence that NSAIDs increase the risk of complications and advice should be given to avoid these agents wherever possible. Surgical resection of the affected segment may be indicated if there are persistent symptoms, or when carcinoma cannot be excluded by radiology or colonoscopy (EBM 16.2).

16.2 Diverticular disease

Fozard JBJ, Armitage NC, Schofield JB, Jones OM. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland Position Statement on Elective Resection for Diverticulitis. http://www.acpgbi.org.uk/assets/documents/Position_Statemen___Elective_Resection_for_Diverticulis.pdf

Jacobs DO. Clinical practice. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 15;357(20):2057-66. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp073228

Complicated diverticular disease

Although most diverticular disease is asymptomatic, serious complications are a frequent cause for emergency admission to surgical wards and are life-threatening and debilitating. Complications of diverticular disease are causally linked to inflammation (Table 16.4). Faeces inspissated in a diverticulum produce stasis and a local inflammatory response. Infection spreads locally and results in peridiverticulitis, producing a low-grade pyrexia and left iliac fossa pain. Persistent infection may cause necrosis and the formation of a peridiverticular abscess. Septic complications are classified by Hinchey grade (Table 16.5). Patients presenting with established diverticular abscess are toxic. Free perforation of the peridiverticular abscess may result. Diverticulitis is also the underlying cause of diverticular bleeding as the feeding arteries are at the apex of each appendix.

| Inflammation |

Table 16.5 Hinchey classification of septic complications of diverticular disease

| Hinchey grade I | Localised para-colonic abscess |

| Hinchey grade II | Distant abscess (e.g. pelvic, sub-phrenic) |

| Hinchey grade III | Purulent peritonitis |

| Hinchey grade IV | Faecal peritonitis |

Large intestinal ischaemia

The aetiology of ischaemia of the large bowel is similar to that of the small intestine. Atheroma at the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery results in relative insufficiency of the arterial supply from the marginal artery (see Fig. 16.2). In rare cases where the inferior mesenteric artery is patent and an abdominal aortic aneurysm is present, colonic infarction may complicate aortic surgery if the inferior mesenteric artery is ligated. Untreated colonic ischaemia often progresses to gangrene and perforation. Some cases present with an acute bloody diarrhoeal illness known as ischaemic colitis, but others may declare symptoms from a chronic stricture.

Ischaemic colitis

In almost 50% of cases, ischaemia of the large intestine is transient and necrosis is confined to the mucosa and submucosa. The patient presents with lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and bloody diarrhoea. Cardiovascular comorbidity should raise suspicion of the diagnosis. Examination reveals tenderness and guarding, often maximal in the lower left abdomen. There is usually a leucocytosis and pyrexia. Plain abdominal radiography may reveal a thickened segment of colon and thumb printing due to submucosal oedema, which may be evident on barium enema or CT (Fig. 16.19). Contrast studies should be carried out with water-soluble contrast such as gastrografin, because of the risk of perforation. The splenic flexure and sigmoid colon are most often affected (Fig. 16.20). Ischaemic colitis is treated conservatively in the first instance unless abdominal signs reveal peritonitis, but symptoms should resolve after a few days of supportive therapy. Further assessment by colonoscopy is indicated once the acute episode has settled, to exclude diverticular disease and colorectal cancer.

Ischaemic stricture of the colon

Colicky abdominal pain, constipation and abdominal distension, following a history of an attack of bloody diarrhoea or a documented episode of ischaemic colitis, may suggest the diagnosis of ischaemic stricture. The patient may present with frank large bowel obstruction. Contrast CT or enema reveals a smooth narrowing of a segment of bowel, with a funnelled appearance at either end but lacking the shouldered appearance of a malignant stricture (Fig. 16.21). Colonoscopy reveals a smooth, narrowed stricture with unremarkable biopsies, or occasionally histology may reveal evidence of chronic fibrosis. Resection is usually required, but some cases never come to medical attention.

Volvulus

Volvulus of the colon most commonly affects the sigmoid colon, and rarely the caecum, and is an important differential diagnosis of any cause of large bowel obstruction, such as cancer and diverticular disease. Sigmoid volvulus is due to a twist around a narrow origin in the sigmoid mesentery. It is an acquired condition and is the most common cause of large bowel obstruction in countries with a high level of dietary fibre and those affected are frequently young adults. By contrast in the UK, patients are usually elderly and chronic constipation is associated. The clinical presentation is of a bowel obstruction with lower abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting and absolute constipation. Occasionally, the patient may present with sepsis owing to an established visceral perforation. Plain radiography reveals a characteristic Y-shaped shadow surrounded by a grossly distended colon arising out of the pelvis on a plain radiograph (‘coffee bean’ sign) (Fig. 16.22). Water-soluble contrast radiography or CT may show the characteristic ‘beaking’ at the site of the twist.

Sigmoid volvulus can be treated conservatively in the emergency situation by reduction and deflation, using rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy and the placement of a large-bore tube into the sigmoid. Elective sigmoid colectomy following full bowel preparation is curative in the fit patient. In frail and demented patients or those with significant cardiac or other comorbidity, a conservative approach may be taken, but a relapse of the twist is very likely and frequent readmission is the rule. Hence, surgery is the preferred option wherever possible (Fig. 16.23).

Intestinal stoma and fistula

Stoma

Intestinal stomas have an important place in the management of small and large intestinal disease. An ileostomy is formed by bringing out the ileum through the abdominal wall, usually through the rectus muscle in the right iliac fossa. Ileal bowel content is irritant to skin and a spout is fashioned to allow appliances to be fitted and so prevent skin contact with bowel content (Fig. 16.24). Ileostomy comprises either an ‘end’ stoma, or a ‘loop’ or ‘defunctioning’ stoma. It may be employed as an adjunct to resectional surgery when the disease process prevents re-anastomosis, or as a temporary stoma to allow a distal anastomosis to heal, such as for a low colorectal or ileoanal anastomosis. End-ileostomy is used when the colon has been removed, and occasionally when small intestine distal to the stoma has been removed, as in extensive Crohn’s disease.

Polyps and polyposis syndromes of the large intestine

The terms ‘polyp’ and ‘tumour’ are not synonymous. A polyp is a descriptive term referring to an excrescence of the mucosa and is not a pathological definition. The histological classification of colorectal polyps into four groups is shown in Table 16.6. Polyps may be identified by rigid sigmoidoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, CT colonography (increasingly) or barium enema (now used increasingly less). Colonoscopy affords the opportunity for polypectomy and so enables histological assessment.

| Type | Solitary | Multiple |

|---|---|---|

| Neoplastic Hamartomatous |

Adenoma (tubular, tubulovillous, villous) Juvenile polyp Peutz–Jeghers polyp |

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS) Cronkhite–Canada syndrome Cowden’s disease |

| Inflammatory | Benign lymphoid polyp | Benign lymphoid polyposis Pseudopolyposis in ulcerative colitis |

| Metaplastic | Metaplastic (hyperplastic)Serrated adenoma | MYH-associated polyposis (MAP) Multiple metaplastic polyps |

Colorectal adenoma

Clinical features

The vast majority of polyps are asymptomatic, but symptoms include rectal bleeding or large bowel colic (especially when a large polyp intussuscepts). Occasionally, a rectal polyp may prolapse through the anus. Patients with giant villous adenoma of the rectum may present with severe watery diarrhea due to excessive mucus loss. This may result in dehydration and electrolyte depletion (profound hyokalaemia is typical). Rectal adenomas may be palpable, but villous tumors are soft and may be missed by the inexperienced finger. Distal polyps are detected readily by sigmoidoscopy, but there is a need for full colonoscopy in view of the risk of synchronous lesions (Fig. 16.25).

Management

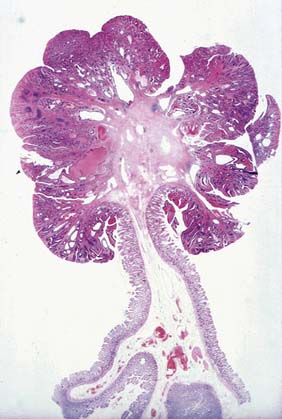

Colonoscopic polypectomy using an electrocautery snare prevents future risk of malignant conversion as well as enabling histological assessment. Small adenomas can be biopsied and a current applied to destroy the entire polyp (‘hot’ biopsy). In many cases, polypectomy is the only treatment required, even when there is a malignant focus, so long as there are none of the following features: poor differentiation, stalk invasion at the resection margin or invasion of submucosal lymphatics or microvasculature (Fig. 16.26). Surgical resection (Fig. 16.27) is indicated following polypectomy if these histological features are noted, since there is a greatly increased risk of bowel wall invasion or lymphatic spread. Polypectomy may be technically impossible or the risk of perforation too high (caecal lesions) and so bowel resection may be indicated for larger polyps. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) allows resection of large rectal villous adenomas and repair of the rectal defect using an operating microscope. Advanced colonoscopic techniques such as lasering or submucosal resection are now well established for larger lesions when surgery is to be avoided.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

FAP is one of the most common single-gene disorders predisposing to cancer and is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. The gene responsible is APC, which is located on the long arm of chromosome 5. In addition to germline changes resulting in FAP, almost every sporadic colorectal cancer has a somatic defect in the APC gene or in other components of the W nt signalling pathway. The annual incidence of FAP is 1 in 6670 live births and the population prevalence is 1 in 13 528. Around 25% of affected individuals have no family history of FAP, the disease arising in these sporadic cases as the result of a new germline mutation. Direct testing for the APC gene is now routine. Clinicopathological diagnosis requires the presence of > 100 adenomatous polyps of the large bowel (Fig. 16.28). Adenomatous polyps usually develop during teenage years and early adulthood, with > 90% chance of colorectal cancer by the third or fourth decade if prophylactic colectomy is not undertaken. Because of effective surgical prophylaxis, FAP now accounts for less than 0.2% of all cases of colorectal cancer in the UK. The prevalence of colorectal cancer at diagnosis is 65% for symptomatic ‘sporadic’ cases and < 5% for screened family members, emphasizing the effectiveness of prophylaxis and surveillance.

Diagnosis and management

The diagnosis can be established by sigmoidoscopy and biopsy. Screening of affected individuals by direct APC gene mutation analysis is used to define the optimal timing of prophylactic surgery. All FAP patients should be referred to a regional genetics service for registration and gene analysis. Pre-symptomatic detection of FAP allows prophylactic colectomy before malignancy supervenes (EBM 16.3). There is no general consensus on the preferred surgical strategy, as both restorative proctocolectomy with ileo-anal pouch formation and total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis have particular advantages. The upper gastrointestinal tract should be screened for duodenal adenoma or carcinoma.

16.3 Colorectal adenomas

Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, Lucassen A, Jenkins P, Fairclough PD, Woodhouse CR; British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland. Gut. 2010 May;59(5):666-89. http://gut.bmj.com/content/59/5/666.long

Malignant tumours of the large intestine

Colorectal adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma of the large bowel is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy. It is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in developed countries. There are ∼︀36 000 new cases in the UK annually, accounting for around 15% and 12% of all cancer registration in males and females respectively. Lifetime risk is ∼︀5%. It is third-ranked cancer overall after lung and prostate in males, and breast and lung in females. The male:female ratio for colon cancer is close to unity, whereas that for rectal cancer is 1.7:1. Incidence rates increase substantially with age. The rectum and sigmoid are particularly common sites for tumours (Fig. 16.29). However, in low-incidence countries, tumours are more evenly distributed. Around 3% of patients present with synchronous tumours, and another 3% develop a metachronous tumour.

Aetiology

Protective agents

Aspirin has been shown conclusively in case-control and cohort epidemiological studies and also recently in randomized trials to substantially reduce colorectal adenoma and cancer risk (variously 30–50% risk reduction). Other NSAIDs also appear to be protective. Dietary calcium supplements and vitamin D also are associated with a reduced risk. Hormone replacement therapy also seems to be protective (EBM 16.4).

Inflammatory bowel disease

The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is discussed above.

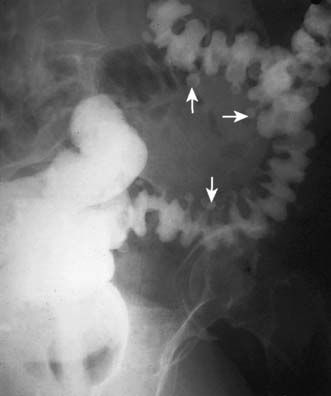

Investigations

Colonoscopy is the investigation of choice (Fig. 16.30). However, increasingly CT colonography (Fig. 16.31) is employed in the investigation of altered bowel habit. It has similar diagnostic accuracy to colonoscopy, although clearly lacks the advantage of enabling diagnostic biopsy or snaring of adenomas. Barium enema (Fig. 16.32) still has a place but is becoming a somewhat obsolete test. Typical features of colorectal cancer are shouldering and mucosal destruction, but biopsy is essential wherever possible. In some instances the diagnosis is only made at laparotomy for a perforated or obstructed viscus.

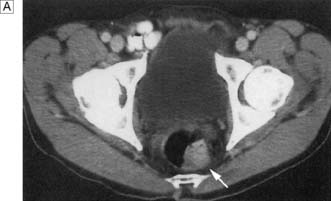

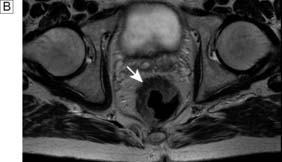

Preoperative staging

Staging is a central component of preoperative work-up, as it provides important information on prognosis, helps inform surgical strategy and indicates the need or otherwise for adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer and adjuvant postoperative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. All patients with colon or rectal cancer should undergo CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 16.33). Liver ultrasound and chest X-ray have now been almost totally superseded by CT. For rectal cancer, digital examination and rigid sigmoidoscopy should be undertaken in every case (examination under anaesthetic – EUA – may be required) to assess the degree of tumour fixity. Pelvic MRI is essential to assess the degree of local invasion of rectal cancer. Endoanal ultrasound may also be useful for local staging of rectal cancer, but is somewhat operator-dependent and requires considerable experience and interpretational skill. In some cases being considered for major debilitating surgery with a view to cure, FDG positron emission tomography in combination with CT scanning (FDG-PET-CT) is indicated. PET-CT has the potential to detect unsuspected distant metastatic disease that can influence the decision to undertake major resectional surgery, rather than more limited procedures.

Management of colorectal adenocarcinoma

Surgery

Elective colorectal resection with curative intent

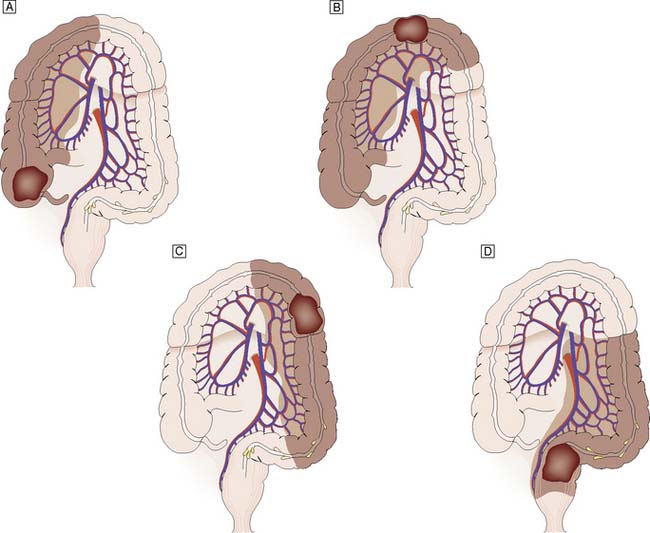

The mainstay of treatment comprises en bloc resection of the primary tumour and loco-regional nodes. This achieves cure in 75% of cases undergoing intended ‘curative’ resections. Excision of the colonic mesentery, ligation of the arterial supply at its origin, and excision of all accompanying lymph nodes achieve locoregional lymphadenectomy for the respective segment of bowel (Fig. 16.34). Resection offers cure for patients with localized disease; even for patients with lymph node metastases but no distant metastases, cure can be expected in 50% of cases with surgery alone. For rectal cancer, excision of the entire mesorectum can reduce local recurrence rates to < 5%. Wherever possible, bowel continuity should be restored. In specialist hands, low rectal cancer should be treated by low anterior resection and colo-anal anastomosis. A colonic J-pouch may be formed in an attempt to improve defaecatory function. However, for low rectal cancer involving the sphincter muscle, it may be necessary to remove the anal sphincter as part of an abdominoperineal resection and fashion a permanent end-colostomy. Laparoscopic colorectal resection is increasingly used and has been shown to provide short-term benefits, with less pain and shorter hospital stay. However, there is no definitive evidence of improved long-term outcomes over open surgery.

Fig. 16.34 Surgical resection for colorectal cancer arising at various locations within the large bowel.

In the elective setting, the patient should be fasted and have undergone full preoperative work-up to assess cardiac, respiratory and any other co-morbidity; reversible risk factors for major surgery should have been addressed. Bowel preparation has been radically reshaped in recent years. Fluid diet is instigated for 48 hours prior to surgery but mechanical bowel preparation is now avoided for the majority of resections and only a phosphate enema 2 hours prior to surgery is required for left sided resections. Recent meta-analyses indicate that there is no benefit for mechanical bowel preparation (comprising polyethylene glycol, sodium picosulfate or phospho-soda), and it may even be harmful. However bowel preparation does have a place for low rectal anastomoses, especially if a defunctioning ileostomy is planned. Antibiotic prophylaxis comprises perioperative broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g. a third-generation cephalosporin, or gentamicin and ampicillin, and metronidazole). Chemical thrombo-prophylaxis (low molecular weight fractionated heparin or calcium heparin), along with compression stockings and intraoperative intermittent pneumatic calf compression (EBM 16.5) is indicated as the risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism is high in such cases.

16.5 Preparation for surgery in patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma

‘Preoperative staging is required to guide surgery and pre-operative adjuvant radiotherapy.

Bowel preparation is not required for colorectal resection.

Patient should be fasted prior to surgery.

Co-morbidity should be addressed wherever possible to limit perioperative mortality risk.

The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the Management of Colorectal Cancer 3rd edition (2007). http://www.acpgbi.org.uk/assets/documents/COLO_guides.pdf

Prevention and management of venous thromboembolism. Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign122.pdf

Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery. Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign104.pdf

Pathology and staging

Macroscopically, colorectal cancer may be polypoidal, ulcerating or stenosing (Fig. 16.35). Two-thirds are ulcerating and a typical lesion has raised everted edges, a slough-covered floor and indurated base. Tumours of the caecum tend to be large exophytic growths. Tumour differentiation may be classified as good, moderate or poor. Around 10–20% of tumours have mucinous histology and this tumour type has a poor prognosis. There is an increasing proportion of proximal tumours in the UK, as right colonic cancer is more common in the elderly and the UK population is ageing.

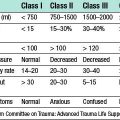

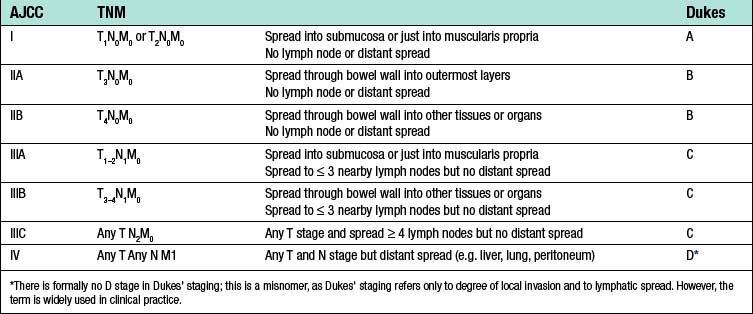

Colorectal cancer may spread by lymphatic invasion, via the portal blood to the liver and/or by trans-peritoneal seeding. Once the peritoneum is breached, dissemination throughout the abdominal cavity is likely. Invasion of lymphatics results in regional lymph node involvement. Very low rectal tumours may also involve the inguinal nodes. Systemic metastases may occur in the later stages of the disease. Tumour staging systems include Dukes’ and TNM staging (Tables 16.7 and 16.8). TNM stages can be grouped using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system (Table 16.9). Pathological staging has important implications for prognosis and also for directing clinical management (EBM 16.6). Staging information informs both predicted survival outcome and also decision-making on whether adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated.

| Dukes’ stage | Description | Proportion of colorectal cancers (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A | Spread into, but not beyond, muscularis propria | 10 |

| B | Spread through full thickness of bowel wall | 30 |

| C | Spread to involve lymph nodes | 30 |

| D* | Distant metastases | 20 |

* There is formally no D stage in Dukes’ staging; this is a misnomer, as Dukes’ staging refers only to degree of local invasion and to lymphatic spread. However, the term is widely used in clinical practice.

Table 16.8 TNM staging of colorectal cancer

| T (Tumour) | |

Table 16.9 American joint committee on cancer (AJCC) stage groupings and equivalence with Dukes’ staging

16.6 Improving postoperative survival rates in colorectal adenocarcinoma

The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the Management of Colorectal Cancer 3rd edition (2007). http://www.acpgbi.org.uk/assets/documents/COLO_guides.pdf

Management of colorectal cancer. Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (and update). Management of colorectal cancer. Guideline No 67. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/67/index.html

Adjuvant therapy

Radiotherapy

Adjuvant preoperative radiotherapy has an important place in the management of rectal cancer, and so preoperative staging of rectal cancer is essential in order to plan optimal management. Radiotherapy has been shown to reduce local recurrence rates but there is no effect on overall survival (EBM 16.6). Most specialist centres in the UK offer selective preoperative radiotherapy for those at increased risk of local recurrence, because there is significant morbidity associated with pelvic irradiation and many patients will be cured by surgery alone. Risk factors include a low tumour, bulky fixed lesion, anterior lesion, evidence of T3 or T4 stage and/or involved lymph nodes on imaging. Either a 5-day short-course regimen of 45 Gy daily or a long-course regimen of 52 Gy given weekly over 3 months is administered. The former is reserved for patients with operable but tethered tumours or very low or anterior tumours, or if extra-rectal spread is evident. Fixed, inoperable tumours are best dealt with by radical radiotherapy over 3 months, and this may be combined with chemotherapy (capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)). Postoperative radiotherapy results in poor bowel function and may damage the small intestine, and hence the importance of preoperative staging to guide administration of radiotherapy before surgery whenever possible.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Systemic adjuvant chemotherapy using 5-FU alone or in combination with other agents has been shown to improve survival for Dukes’ C colorectal cancer after surgical resection (EBM 16.6). Intravenous regimens employing intravenous 5-FU has largely been replaced in current practice by targeting the same pathway through inhibition of thymidylate synthase using chemical inhibitors such as capecitabine. Capecitabine is less toxic than 5-FU and can be administered orally. There is an overall 30% improvement in survival for patients with Dukes’ C tumours who receive chemotherapy, equating with an 11% absolute improvement in survival for that group and a 6% overall improvement in survival for patients with colorectal cancer of all stages. In the UK, it is now routine practice to offer chemotherapy based on 5-FU to all patients with stage C cancers who do not have significant comorbidity, particularly cardiovascular disease. Regimens now routinely combine capecitabine with oxaliplatin as first line therapy. Recently, it has also been shown that Dukes’ B tumours gain modest survival benefit (∼︀2%). However, adjuvant chemotherapy for Dukes’ B tumours is restricted to poor-prognosis lesions (poor differentiation, venous or lymphatic invasion). Capecitabine (or 5-FU) chemotherapy is considered a conventional ‘first-line’ chemotherapeutic regimen for colorectal cancer. Other newer agents, such as cetuximab (monoclonal antibody to epidermal growth factor receptor) and bevacizumab (antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor), have shown promise in patients with relapsed disease after first-line chemotherapy. Other agents such as temozolomide, used either alone or in combination with other standard agents are also used in relapsed disease and in trials. Although irinotecan (CPT-11) showed initial promise, a number of negative trials indicate it may only have a place in the management of a small selected subset of patients.

Palliative therapy

Summary Box 16.5 Colorectal cancer

• Colorectal adenocarcinoma is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy, with 36 000 cases per annum in the UK

• It is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in developed countries, accounting for 15% of all cancers in males and 12% in females, with a 5% lifetime risk

• 2–3% of patients present with synchronous tumours, and a further ∼︀3% develop metachronous tumours

• Risk factors include male gender, increasing age, family history of an affected relative, ‘westernized’ diet, inflammatory bowel disease and pre-existing adenomatous polyps

• Genes have been identified for a number of autosomal dominant colorectal cancer predisposition syndromes, accounting for ∼︀3% of all cases.

• Around 35% of the aetiology of colorectal cancer is attributable to genetic factors and a number of common genetic variants have recently been identified, offering future potential for genetic profiling

• Two-thirds of all large bowel cancers occur in the rectum and sigmoid colon, and the most common clinical features are alteration in bowel habit and the passage of blood per rectum

• Diagnosis involves colonoscopy and biopsy, CT colonography, or barium enema (used less). Preoperative staging involves CT, MRI and PET-CT scanning

• Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, involving radical local clearance combined with regional lymphadenectomy

• Adjuvant therapy options include preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer and postoperative chemotherapy

• Pre-symptomatic diagnosis may be achieved by population screening using faecal occult blood testing or by surveillance colonoscopy in high-risk groups

• Overall 5-year survival is 55%. Staging systems provide useful prognosis to guide therapy and inform patients of expected outcome.