Chapter 15 The skin, nails, and lumps

The dermatological history

With any rash or skin condition, it is important to determine when and where it began, its distribution, whether it has changed over time, its relationship to sun exposure or heat or cold, and any response to treatment1 (see Questions box 15.1). Ask if pruritus is associated; localised pruritus is usually due to dermatological disease. Determine if pain or disturbed sensation has occurred; for example, inflammation and oedema can produce pain in the skin, while disease involving neurovascular bundles or nerves can produce anaesthesia (e.g. leprosy, syphilis). Constitutional symptoms such as fever, headache, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss also need to be documented.

Questions box 15.1

A detailed social history needs to be obtained regarding occupation and hobbies, as chemical exposure and contact with animals or plants can all induce dermatitis. All medications that have been taken must be documented. Orally ingested or parenteral medications can cause a whole host of cutaneous lesions and can mimic many skin diseases (Table 15.1). Similarly, a family history of atopic dermatitis, hay fever or skin infestation can be helpful.

| 1 Acne, e.g. steroids |

| 2 Hair loss (alopecia), e.g. cancer chemotherapy |

| 3 Pigment alterations: hypomelanosis (e.g. hydroxyquinone, chloroquine, topical steroids), hypermelanosis (page 449) |

| 4 Exfoliative dermatitis or erythroderma (page 448) |

| 5 Urticaria (hives), e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, radiographic dyes, penicillin |

| 6 Maculopapular (morbilliform) eruptions, e.g. ampicillin, allopurinol |

| 7 Photosensitive eruptions, e.g. sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, chlorothiazides, phenothiazines, tetracycline, nalidixic acid, anticonvulsants |

| 8 Drug-induced lupus erythematosus, e.g. procainamide, hydralazine |

| 9 Vasculitis, e.g. propylthiouracil, allopurinol, thiazides, penicillin, phenytoin |

| 10 Skin necrosis, e.g. warfarin |

| 11 Drug-precipitated porphyria, e.g. alcohol, barbiturates, sulfonamides, contraceptive pill |

| 12 Lichenoid eruptions, e.g. gold, antimalarials, beta-blockers |

| 13 Fixed drug eruption, e.g. sulfonamides, tetracycline, phenylbutazone |

| 14 Bullous eruptions, e.g. frusemide, nalidixic acid, penicillamine, clonidine |

| 15 Erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme (page 448) |

| 16 Toxic epidermal necrolysis, e.g. allopurinol, phenytoin, sulfonamides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| 17 Pruritus (page 445) |

Examination anatomy

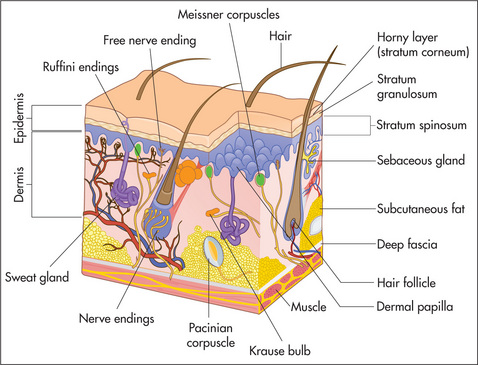

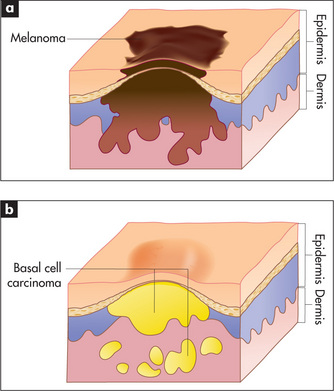

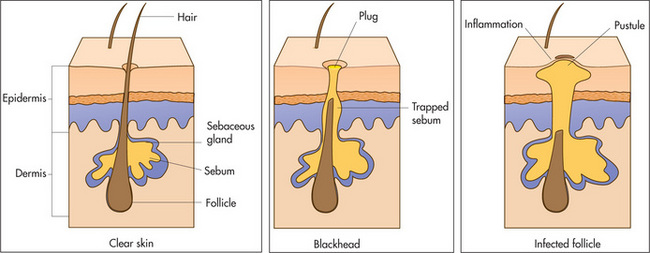

Figure 15.1 shows the three main layers of the skin—epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous fat. These layers can all be involved in skin diseases in varying combinations. For example, most skin tumours arise in the epidermis (Figure 15.2a&b), some bullous eruptions occur at the epidermo-dermal junction, and lipomas are tumours of subcutaneous fat. The skin appendages which include the sweat (eccrine and apocrine) glands, hair follicles (Figure 15.3) and the nails are common sites of infection.

The nails are formed from heavily keratinised cells that grow from the nail matrix. The matrix grows in a semilunar shape and appears as the lunules in normal finger and toe nails. Hair is also the product of specialised epithelial cells and grows from the hair matrix within the hair follicle.

General principles of physical examination of the skin

The aim of this chapter is to provide an approach to the diagnosis of skin diseases.2,3 Particular emphasis will be placed on cutaneous signs as indications of systemic disease. Other chapters have included the usual clues that can be used to arrive at a particular diagnosis. This chapter tries to unify the concept of ‘inspection’ as a valuable starting point in the examination of the patient.

Ask the patient to undress. The whole surface of the skin and its appendages should be carefully inspected (Table 15.2).

| 1 Hair |

| 2 Nails |

| 3 Sebaceous glands—oil-producing and present on the head, neck and back |

| 4 Eccrine glands—sweat-producing and present all over the body |

| 5 Apocrine glands—sweat-producing and present in the axillae and groin |

| 6 Mucosa |

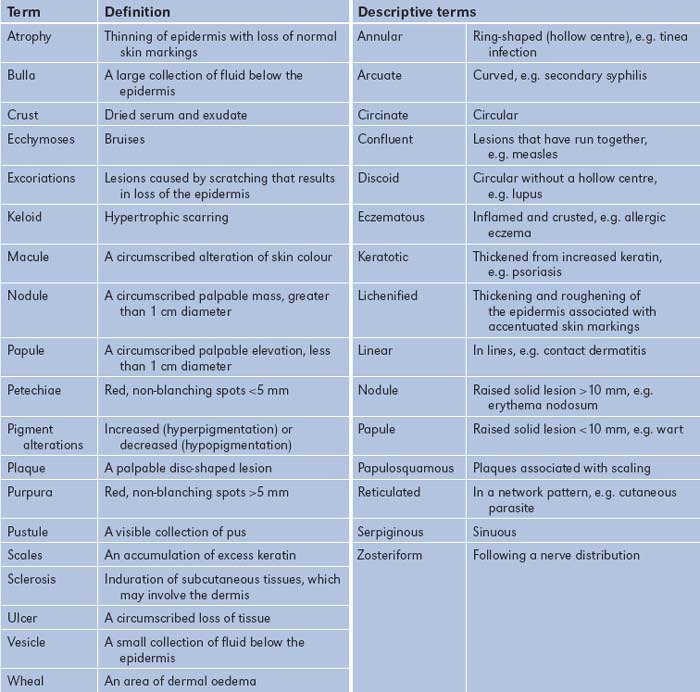

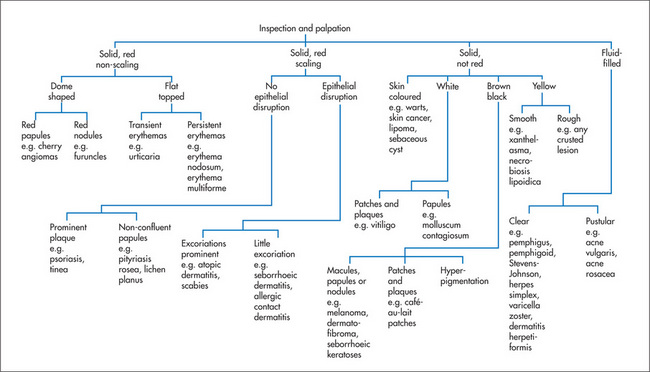

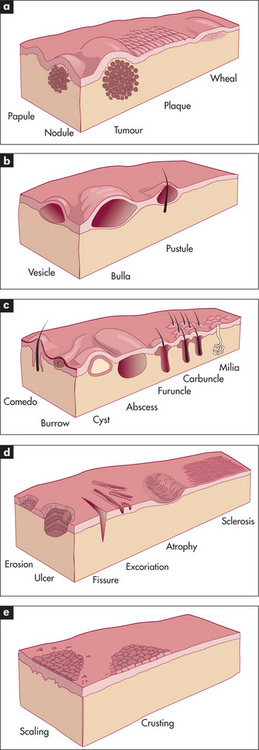

When one is examining actual skin lesions, a number of features should be documented. First, each lesion should be described precisely, including colour and shape. Use the appropriate dermatological terminology (Table 15.3), even though this may seem to make dermatological diseases more, rather than less, mysterious. As many dermatological diagnoses are purely descriptive, a good description will often be of considerable help in making the diagnosis. Second, the distribution of the lesions should be noted, as certain distributions suggest specific diagnoses. Third, the pattern of the lesions—such as linear, annular (ring-shaped), reticulated (net-like), serpiginous (snake-like) or grouped—also helps establish the diagnosis. Then palpate the lesions, noting consistency, tenderness, temperature, depth and mobility. Types of skin lesions are shown in Figure 15.4 and a clinical algorithm for diagnosis is presented in Figure 15.5.

Figure 15.4 Types of skin lesions

(a) Primary skin lesions, palpable with solid mass.

(b) Primary skin lesions, palpable and fluid-filled.

(c) Special primary skin lesions.

(d) Secondary skin lesions, below the skin plane.

(e) Secondary skin lesions, above the skin plane.

Adapted from Schwartz M. Textbook of physical diagnosis, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

How to approach the clinical diagnosis of a lump

First, determine the lump’s site, size, shape, consistency and tenderness. Next, evaluate in what tissue layer the lump is situated. If it is in the skin (e.g. sebaceous cyst, epidermoid cyst, papilloma), it should move when the skin is moved, but if it is in the subcutaneous tissue (e.g. neurofibroma, lipoma), the skin can be moved over the lump. If it is in the muscle or tendon (e.g. tumour), then contraction of the muscle or tendon will limit the lump’s mobility. If it is in a nerve, pressing on the lump may result in pins and needles being felt in the distribution of the nerve, and the lump cannot be moved in the longitudinal axis but can be moved in the transverse axis. If it is in bone, the lump will be immobile.

Place a small torch behind the lump to determine whether it can be transilluminated.

Note any associated signs of inflammation (i.e. heat, redness, tenderness and swellinga).

Look for similar lumps elsewhere, such as multiple subcutaneous swellings from neurofibromas or lipomas. Neurofibromas are smaller than lipomas. They look hard but are remarkably soft; they occur in neurofibromatosis Type 1 (von Recklinghausen’sb disease). They continue to increase in number throughout life and are associated with café-au-lait spots and sometimes spinal neurofibromas.

Correlation of physical signs and skin disease

There are many different skin diseases with varied physical signs. With each major sign the groups of common important diseases that should be considered will be listed.

Pruritus

To determine the cause of the pruritus it is essential to examine the skin in detail (Table 15.4). Excoriations are caused by scratching, regardless of the underlying cause. Specific features of cutaneous diseases such as dermatitis, scabies (Figure 15.6) or the blisters of dermatitis herpetiformis should be looked for.

| 1 Asteatosis (dry skin) |

| 2 Atopic dermatitis (erythematous, oedematous papular patches on head, neck, flexural surfaces) |

| 3 Urticaria |

| 4 Scabies |

| 5 Dermatitis herpetiformis |

When primary skin diseases have been excluded, a detailed history and examination should be undertaken to consider the various systemic diseases listed in Table 15.5.

TABLE 15.5 Systemic conditions causing pruritus

| 1 Cholestasis, e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis |

| 2 Chronic renal failure |

| 3 Pregnancy |

| 4 Lymphoma and other internal malignancies |

| 5 Iron deficiency, polycythaemia rubra vera |

| 6 Endocrine diseases, e.g. diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, carcinoid syndrome |

Erythrosquamous eruptions

Asymptomatic lesions on the palms and soles are suggestive of secondary syphilis, whereas itchy lesions in the same location would be more suggestive of lichen planus (Figures 15.7 and 15.8). Lichen planus is occasionally associated with primary biliary cirrhosis and other liver diseases, chronic graft-versus-host disease and drugs (e.g. gold, penicillamine). Scattered lesions of recent origin on the trunk would be more suggestive of pityriasis rosea (Figure 15.9), whereas more widespread, diffuse and intensely itchy lesions would be more suggestive of nummular eczema (Figure 15.10) (Table 15.6).

Figure 15.8 Lichen planus

With development of lesions in an area of trauma—the ‘Koebner’ phenomenon.

| 1 Psoriasis (bright pink plaques with silvery scale) |

| 2 Atopic eczema (diffuse erythema with fine scaling) |

| 3 Pityriasis rosea (paler pink, scaly, macular lesions in a Christmas tree pattern; herald patch; self-limited) |

| 4 Nummular eczema (round patches of subacute dermatitis) |

| 5 Contact dermatitis (irritant or allergic) |

| 6 Dermatophyte infections (ringworm) |

| 7 Lichen planus (violet-coloured, small, polygonal papules) |

| 8 Secondary syphilis (flat, red, hyperkeratotic lesions) |

Scaly lesions with a well-demarcated edge over the extensor surfaces are usually due to psoriasis (Figures 15.11 and 15.12).

Blistering eruptions

There are a number of different diseases which will present with either vesicles or blisters (Table 15.7). Dermatitis can present as a blistering eruption, particularly acute contact dermatitis (Figure 15.13). See Questions box 15.2.

| 1 Traumatic blisters and burns |

| 2 Bullous impetigo |

| 3 Viral blisters (e.g. herpes simplex, varicella) |

| 4 Bullous erythema multiforme |

| 5 Bullous pemphigoid |

| 6 Dermatitis herpetiformis |

| 7 Pemphigus |

| 8 Porphyria |

| 9 Epidermolysis bullosa |

| 10 Dermatophyte infections |

| 11 Acute contact dermatitis |

Figure 15.13 Allergic contact dermatitis

From over-the-counter topical medication rubbed over congested sinuses.

Questions box 15.2

Questions to ask the patient with a blistering eruption

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

Clinical features of bullous eruptions

Viral blisters such as those of herpes simplex virus infection (Figure 15.14) have a distinctive morphology (grouped vesicles on an erythematous background).

Pemphigus vulgaris is much more severe. It has thin-roofed blisters that readily rupture and form crusts. The affected superficial skin can be moved over the deeper layer (Nikolsky’sc sign). Oral ulcers are common.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is characterised by a very itchy widespread vesicular or bullous eruption.

Porphyria cutanea tarda is characterised by clear or haemorrhagic tense blisters on the hands and other sun-exposed areas, hyperpigmentation and increased facial hair; many patients have hepatitis C and alcohol can induce symptoms (due to decreased uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase).

Erythroderma

Erythroderma is best thought of as the end-stage of numerous skin conditions (Table 15.8). The erythrodermic patient has involvement of nearly all the skin with an erythematous inflammatory process, often with exfoliation. There is usually associated oedema and loss of muscle mass. This represents that most unusual occurrence, a dermatological emergency.

| 1 Eczema |

| 2 Psoriasis |

| 3 Drugs, e.g. phenytoin, allopurinol |

| 4 Pityriasis rubra pilaris |

| 5 Mycosis fungoides, leukaemia, lymphoma |

| 6 Lichen planus |

| 7 Pemphigus foliaceus |

| 8 Hereditary disorders |

| 9 Dermatophytosis |

Pustular and crusted lesions

It is essential to determine whether or not a pustular lesion (or a group of pustular lesions) represents a primarily infectious process or an inflammatory dermatological condition. For example, pustular lesions on the hands and feet may either be due to tinea infection or be a primary pustular psoriasis or palmoplantar pustulosis (Table 15.9). See Questions box 15.3.

| 1 Acne vulgaris (comedones, papules, pustules, cystic lesions, ice pick scars—no telangiectasiae) |

| 2 Acne rosacea (acne-like lesions, erythema and telangiectasia on central face) |

| 3 Impetigo |

| 4 Folliculitis |

| 5 Viral lesions |

| 6 Pustular psoriasis |

| 7 Drug eruptions |

| 8 Dermatophyte infections |

Dermal plaques

Plaques are localised thickenings of the skin which are usually caused by changes in the dermis or subcutaneous fat. These may be due to chronic inflammatory processes or scarring sclerotic processes (Table 15.10).

| 1 Granuloma annulare |

| 2 Necrobiosis lipoidica |

| 3 Sarcoidosis |

| 4 Erythema nodosum |

| 5 Lupus erythematosus |

| 6 Morphoea and scleroderma |

| 7 Tuberculosis |

| 8 Leprosy |

Erythema nodosum

This is the best known of the group of diseases classified as nodular vasculitis. The lesions of erythema nodosum are usually found below the knee in the pretibial area and are erythematous, palpable and tender (Figure 6.36, page 191). There may be an associated fever (Table 15.11). Sarcoidosis is a common cause, but the skin changes in sarcoid can mimic almost any skin disease (except vesicles).

| 1 Sarcoidosis |

| 2 Streptococcal infections (β-haemolytic) |

| 3 Inflammatory bowel disease |

| 4 Drugs, e.g. sulfonamides, penicillin, sulfonylurea, oestrogen, iodides, bromides |

| 5 Tuberculosis |

| 6 Other infections, e.g. lepromatous leprosy, toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis, Yersinia, Chlamydia |

| 7 Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| 8 Behçet’s syndrome |

Erythema multiforme

This is a distinctive inflammatory reaction of skin and mucosa. It is not a systemic disease. Characteristic discrete target lesions occur, particularly on the distal extremities (Figure 15.15). The periphery of these lesions is red, whereas the centre becomes bluish or even purpuric. The lesions can become bullous, and severe cases of this syndrome involve widespread desquamation of the mucosal surfaces (the Stevens-Johnsond syndrome). In many cases the condition is precipitated by clinical or subclinical herpes simplex virus infection. Other causes include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, histoplasmosis, malignancy, sarcoidosis and drugs (including those that can cause toxic epidermal necrolysis). Sometimes no underlying cause of the erythema multiforme will be established.

Hyperpigmentation

The presence of hyperpigmentation can be a clue to underlying systemic disease (Table 15.12).

| Endocrine disease |

| Addison’s disease (excess ACTH) |

| Ectopic ACTH secretion (e.g. carcinoma) |

| The contraceptive pill or pregnancy |

| Thyrotoxicosis, acromegaly, phaeochromocytoma |

| Metabolic |

| Malabsorption or malnutrition |

| Liver diseases, e.g. haemochromatosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, Wilson’s disease |

| Chronic renal failure |

| Porphyria |

| Chronic infection, e.g. bacterial endocarditis |

| Connective tissue disease, e.g. systemic lupus, scleroderma, dermatomyositis |

| Racial or genetic |

| Other |

| Drugs, e.g. chlorpromazine, busulphan, arsenicals |

| Radiation |

ACTH = adrenocorticotrophic hormone.

Flushing and sweating

Flushing of the skin may sometimes be observed, especially on the face, by the examiner. Some of the causes of this phenomenon are presented in Table 15.13.

| 1 Menopause |

| 2 Drugs and foods, e.g. nifedipine, monosodium glutamate (MSG) |

| 3 Alcohol after taking the drug disulfiram (or alcohol alone in some people) |

| 4 Systemic mastocytosis |

| 5 Rosacea |

| 6 Carcinoid syndrome (secretion of serotonin and other mediators by a tumour may produce flushing, diarrhoea and valvular heart disease) |

| 7 Autonomic dysfunction |

| 8 Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid |

Skin tumours

Skin tumours are very common and are usually benign (Table 15.14).4 Most malignant skin tumours can be cured if they are detected early and treated appropriately (Table 15.15).

| 1 Warts |

| 2 Molluscum contagiosum |

| 3 Seborrhoeic keratoses |

| 4 Dermatofibroma |

| 5 Neurofibroma |

| 6 Angioma |

| 7 Xanthoma |

TABLE 15.15 Malignant skin tumours

| 1 Basal cell carcinoma |

| 2 Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 3 Bowen’s* disease (squamous cell carcinoma confined to the epithelial layer of the skin—carcinoma in situ) |

| 4 Malignant melanoma |

| 5 Secondary deposits |

* John Templeton Bowen (1857–1941), Boston dermatologist.

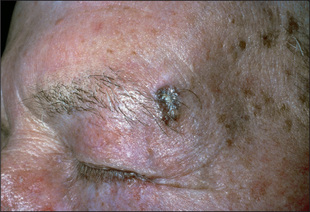

The earliest lesions are actinic (solar) keratoses, which are pink macules or papules surmounted by adherent scale (Figure 15.16). Basal cell carcinoma is characteristically a translucent papule with a depressed centre and a rolled border with ectatic capillaries (Figure 15.17). Squamous cell carcinoma is typically an opaque papule or plaque which is often eroded or scaly (Figure 15.18).

Figure 15.16 Actinic keratosis, slightly eroded and scaly

Higher on the forehead additional granular keratosis could be easily palpated.

Figure 15.17 Pigmented basal cell carcinoma

With pearly quality and depressed centre, in a patient with sun-damaged skin.

Malignant melanomas are usually deeply pigmented lesions that are enlarging and have an irregular notched border (Figure 15.19). There is often variation of pigment within the lesion. Malignant melanoma is likely if the lesion is Asymmetrical, has an irregular Border, has an irregular Colour and is large (Diameter >6 mm) and may be Elevated, referred to as the ABCDE checklist.5,6 Patients with numerous large and unusual pigmented naevi (dysplastic naevus syndrome) are at an increased risk of developing malignant melanoma.

The nails

Fungal infection of the nails (onychomycosis) (Figure 15.20) is their most common abnormality. It makes up 40% of all nail disorders and 30% of all cutaneous fungal infections. The characteristic findings are pitting, thickening, ridging and deformity. The changes can be indistinguishable from those of psoriasis. Candidal nail infections are less common than those due to dermatophytes. Candidal nail infection (diagnosed by microscopy and culture) suggests the possibility of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, which is a rare condition associated with polyendocrinopathies.

Nail involvement occurs in about 25% of patients with psoriasis (Figure 15.21). The characteristic abnormality is pitting. This can also occur in fungal infections, chronic paronychia, lichen planus and alopecia areata. Psoriasis is also the most common cause of onycholysis. Rarer changes in psoriatic nails include longitudinal ridging (onychorrhexis), proximal transverse ridging, subungual hyper-keratosis and yellow-brown discoloration.

Summary

The dermatological examination in internal medicine: a suggested method

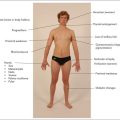

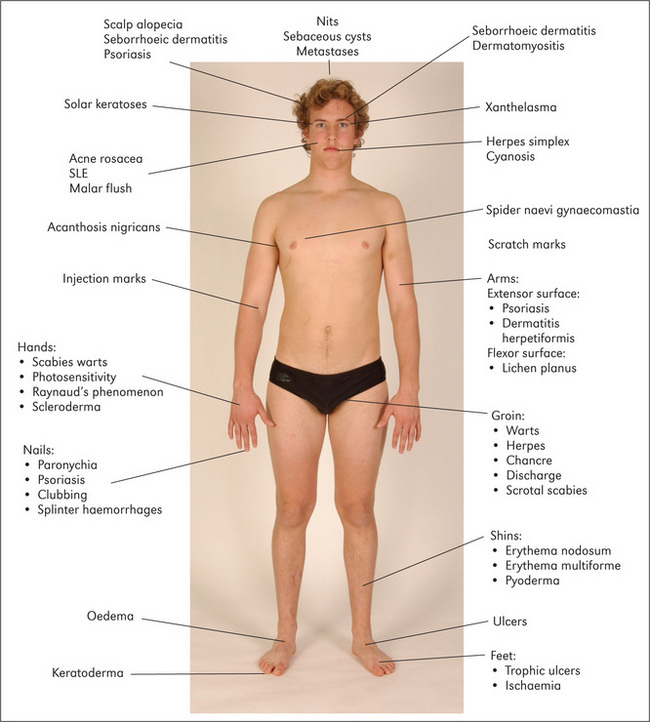

Figure 15.22 Sites of some important skin lesions of the limbs, face and trunk SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Look at the face for rosacea, which causes bright erythema of the nose, cheeks, forehead and chin, and occasionally pustules and rhinophyma (disfiguring swelling of the nose). Acne causes papules, pustules and scars involving the face, neck and upper trunk. The butterfly rash of systemic lupus erythematosus occurs across the cheeks but is rare. Spider naevi may be present. Ulcerating lesions on the face may include basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma or rarely tuberculosis (lupus vulgaris).

Go on to inspect the trunk, where any of the childhood exanthems produce their characteristic rashes. Look for spider naevi. Campbell de Morgan spots are commonly found on the abdomen (and chest), as are flat, greasy, yellow-coloured seborrhoeic warts. Erythema marginatum (rheumatic fever) occurs on the chest and abdomen. Herpes zoster may be seen overlying any of the dermatome distributions.

1. Marks R. A diagnostic approach to common dermatology problems. Aust Fam Phys. 1982;11:696-702.

2. Ashton RE. Teaching non-dermatologists to examine the skin: a review of the literature and some recommendations. Brit J Derm. 1995;132:221-225.

3. Schwarzenberger K. The essentials of the complete skin examination. Med Clin Nth Am. 1998;82:981-999.

4. Preston DS, Stern RS. Nonmelanoma cancers of the skin. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:649-662. Provides useful information on discriminating between worrying and non-worrying lesions, and includes colour photographs

5. Whitehead JD, Gichnik JM. Does this patient have a mole or a melanoma?. JAMA 1998;279:696-701. The ABCD checklist (asymmetry, border irregularity, irregular colour, diameter >6 mm) has a sensitivity over 90% and a specificity over 95% for identifying malignant melanoma.

6. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: rewriting the ABC criteria. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

Buxton PK. ABC of dermatology, 5th edn. London: Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Callen JP, Paller AS, Greer K, editors. Color atlas of dermatology, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000.

Fitzpatrick TB, Johnson RA, Polano MK, Suurmond D, Wolff K. Color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology, 5th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

Gawkrodger DJ. Dermatology. An illustrated color text, 4th edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

a These four cardinal signs were described by Celsus in the 8th volume of his medical book which taught those who were interested surgical techniques. After performing surgery readers were warned to look out for the four cardinal signs of post-surgical inflammation—calor, rubor, dolor and tumor. Modern surgeons have added loss of function to these signs.

b Frederich von Recklinghausen (1833–1910). He was Virchow’s assistant in Berlin and then professor of pathology in Strasbourg from 1872. He described this disease in 1882 and haemochromatosis in 1889.

c Pyotr Vasilyevich Nikolsky (1855–1940), Kiev and Warsaw dermatologist. Nikolsky’s sign also occurs in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

d Albert Mason Stevens (1884–1945), New York paediatrician, and Frank C Johnson (1894–1934), American physician.