The skin in old age

In westernized societies, the proportion of people aged over 65 is high and continues to rise. Poor nutrition, lack of self-care and general illness contribute to skin disease in the elderly. Few people die from old skin, but many suffer from it.

Intrinsic ageing of the skin

The changes in aged, sun-protected skin are more subtle than those of photoageing (p. 107) and consist of laxity, fine wrinkling and benign neoplasms. In addition, androgenetic alopecia (p. 66) and greying of the hair are age related.

Some inherited disorders, e.g. pseudoxanthoma elasticum (p. 93), show features of aged skin. The misuse of potent topical steroids induces atrophy and purpura (p. 114), signs also seen in old skin.

Dermatoses in the elderly

Few skin conditions are exclusive to old age, but some are seen more frequently (Table 1).

| The eczemas | |

| Other eruptions | |

| Infections | |

| Ulceration |

Dry skin and asteatotic eczema

Dryness with itching is common in elderly skin. It may be a mild roughness and scaling, or more severe, with fissuring and inflammation (asteatotic eczema, p. 38). The changes often occur on the legs and are aggravated by low humidity, central heating and excessive washing. Emollients, sometimes with a mild or moderate potency topical steroid ointment, usually help.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis (p. 38) in the elderly (Fig. 1) may be flexural and resemble psoriasis, candidiasis or erythrasma. In old people, allergic contact dermatitis (p. 34) to allergens in topical medicaments or toiletries, e.g. lanolin, neomycin, fragrances and local anaesthetics, particularly needs to be considered.

Pruritus

Itch in old age can be severe and unrelenting. Examination will usually show asteatotic eczema, scabies, urticaria or the prebullous phase of pemphigoid (p. 78), or investigations may reveal renal or liver disease or underlying malignancy (p. 88). The small group of patients in whom no cause is found have ‘senile pruritus’. Topical treatments and sedating antihistamines are often ineffective.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis has its peak onset in the teens with a second peak in the sixth decade. In the elderly patient, it is frequently flexural (p. 28), but all patterns, except guttate, are seen. Management can be difficult due to inability to apply topical therapy, attend hospital or stand for ultraviolet treatment. Methotrexate is used quite often and is mostly well tolerated.

Infections and infestations

Herpes zoster (p. 54) at some time affects 25% of people over 65. Post-herpetic neuralgia increases with age, occurring in 75% of shingles victims over 70. Early treatment with antivirals (e.g. aciclovir) together with amitriptyline or gabapentin makes neuralgia less likely.

Infection with Candida albicans (p. 58) is common in the flexures of obese elderly women. Onychomycosis (p. 68) is a frequent incidental finding in old people, especially men. Treatment is not always needed unless the nail produces pain.

Scabies epidemics are a problem in old people’s homes and are difficult to control (p. 62). Any itchy old person should be examined carefully, as burrows are easily missed. Elderly patients who are debilitated, paralysed, immunosuppressed or who cannot scratch may develop crusted ‘Norwegian’ scabies (Fig. 2), which is highly contagious due to the thousands of mites present.

Photodamage and skin tumours

Most benign and malignant skin tumours are more common in the elderly (Table 1). Many are related to sun exposure (p. 107). Specific disorders of photodamage include:

Actinic (solar) keratoses: these are single or multiple, discrete, scaly, hyperkeratotic, rough-surfaced areas, usually less than 1 cm in diameter. They are seen on sun-exposed sites, especially the dorsal aspects of the hands, face and neck (Fig. 3). They are most common in those with a fair skin.

Actinic (solar) keratoses: these are single or multiple, discrete, scaly, hyperkeratotic, rough-surfaced areas, usually less than 1 cm in diameter. They are seen on sun-exposed sites, especially the dorsal aspects of the hands, face and neck (Fig. 3). They are most common in those with a fair skin.

Histologically, they show hyperkeratosis, abnormal keratinocytes with loss of maturation and dermal elastosis. Actinic keratoses may regress spontaneously. However, they can progress to squamous cell carcinoma, although this is relatively uncommon. Treatment is normally by cryosurgery, but certain lesions may be best treated with curettage, excision or by applying 5% fluorouracil cream (Efudix) once or twice daily for 3–4 weeks, 3% diclofenac gel (Solaraze) twice daily for 60–90 days or imiquimod (Aldara). Photodynamic therapy is a useful option in widespread (‘field’) actinic damage (p. 113).

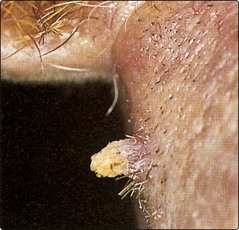

A cutaneous horn may occasionally develop in an actinic keratosis (Fig. 4). It is best treated by excision.

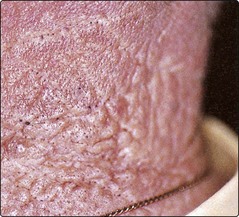

Actinic (solar) elastosis: in solar elastosis, the sun-exposed skin is yellowed, thickened and wrinkled. On the neck, furrowed rhomboidal patterns are sometimes seen (Fig. 5), particularly in those with outside occupations such as farmers. ‘Senile’ comedones or thickened yellowish plaques may develop. Photodamage is worse in smokers.

Actinic (solar) elastosis: in solar elastosis, the sun-exposed skin is yellowed, thickened and wrinkled. On the neck, furrowed rhomboidal patterns are sometimes seen (Fig. 5), particularly in those with outside occupations such as farmers. ‘Senile’ comedones or thickened yellowish plaques may develop. Photodamage is worse in smokers.

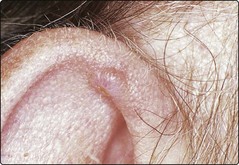

Damaged dermal collagen with inflammation in the dermis and cartilage is a feature of chondrodermatitis nodularis (p. 95, Fig. 6). Treatment is by excision, although some early lesions can be halted by topical glucocorticoid treatment.

Damaged dermal collagen with inflammation in the dermis and cartilage is a feature of chondrodermatitis nodularis (p. 95, Fig. 6). Treatment is by excision, although some early lesions can be halted by topical glucocorticoid treatment.

Actinic cheilitis: excessive exposure to sun, often occupational, can induce inflammation and scaling of the lower lip. Treatment options are the same as for actinic keratoses. Diagnostic histology is recommended in thickened, tender or new lesions because squamous cell carcinoma can be missed.

Actinic cheilitis: excessive exposure to sun, often occupational, can induce inflammation and scaling of the lower lip. Treatment options are the same as for actinic keratoses. Diagnostic histology is recommended in thickened, tender or new lesions because squamous cell carcinoma can be missed.

Ulceration

Leg ulcers: venous ulcers often start in middle age but, because of their chronicity, are a problem in the elderly. Ischaemic ulcers become more common with advancing years (p. 73).

Leg ulcers: venous ulcers often start in middle age but, because of their chronicity, are a problem in the elderly. Ischaemic ulcers become more common with advancing years (p. 73).

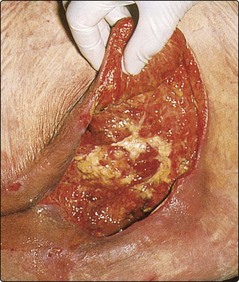

Pressure ulcers: a pressure ulcer starts as an area of erythema and progresses to widespread necrosis of tissue with ulceration. Deep ulcers develop over the sacrum (Fig. 7), heels, ischia and greater trochanters. Secondary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa is common.

Pressure ulcers: a pressure ulcer starts as an area of erythema and progresses to widespread necrosis of tissue with ulceration. Deep ulcers develop over the sacrum (Fig. 7), heels, ischia and greater trochanters. Secondary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa is common.

The skin in old age

Asteatotic eczema (also known as eczéma craquelé) is a dry, scaly, fissured eruption that commonly affects the elderly. Treatment is with emollients and mild topical steroids.

Asteatotic eczema (also known as eczéma craquelé) is a dry, scaly, fissured eruption that commonly affects the elderly. Treatment is with emollients and mild topical steroids.

Pruritus in old people nearly always has a cause. Scabies, urticaria or prebullous pemphigoid are easily missed. Investigation for underlying systemic disease may be indicated.

Pruritus in old people nearly always has a cause. Scabies, urticaria or prebullous pemphigoid are easily missed. Investigation for underlying systemic disease may be indicated.

Herpes zoster is common in old age. Aciclovir or famciclovir may make neuralgia less likely.

Herpes zoster is common in old age. Aciclovir or famciclovir may make neuralgia less likely.

Actinic keratoses are roughened hyperkeratotic areas in sun-exposed sites. They are often treated by cryosurgery or the application of fluorouracil cream or diclofenac gel.

Actinic keratoses are roughened hyperkeratotic areas in sun-exposed sites. They are often treated by cryosurgery or the application of fluorouracil cream or diclofenac gel.

Actinic elastosis is a yellowed, thickened, wrinkled change in sun-exposed skin, e.g. on the neck, often seen in men who have had outdoor occupations.

Actinic elastosis is a yellowed, thickened, wrinkled change in sun-exposed skin, e.g. on the neck, often seen in men who have had outdoor occupations.

Pressure ulcers result from reduced sensation, immobility, malnutrition and ischaemia. It is vital to identify at-risk patients and institute means to prevent these ulcers from developing.

Pressure ulcers result from reduced sensation, immobility, malnutrition and ischaemia. It is vital to identify at-risk patients and institute means to prevent these ulcers from developing.