Chapter 5

The Skin

What is the hardest of all? That which you hold the most simple; seeing with your own eyes what is spread out before you.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)

General Considerations

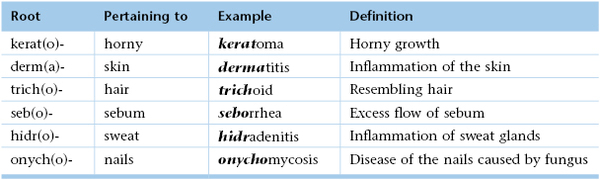

The skin, which is the largest organ of the body, is one of the best indicators of general health. Even a person without medical training is capable of detecting changes in skin color and texture. The trained examiner can detect these changes and at the same time evaluate more subtle cutaneous signs of systemic disease.

Diseases of the skin are common. Approximately one third of the population in the United States has a disorder of the skin that warrants medical attention. Nearly 8% of all adult outpatient visits are related to dermatologic problems. Basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (i.e., nonmelanotic skin cancers [NMSCs]) are by far the most common malignancies that occur in the United States. One of every three new cancers is a skin cancer, and the vast majority are basal cell carcinomas. Approximately 80% of the new skin cancer cases are basal cell carcinoma, 16% are squamous cell carcinoma, and 4% are melanoma. Most of these cases occur on the head and neck, which is evidence of the importance of sun exposure as a causative stimulus. Squamous cell carcinoma, the second most common skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma, afflicts more than 200,000 Americans each year. Although in most of these patients the cancer is treated and cured, skin cancer still causes more than 5000 deaths a year.

Melanoma is responsible for most skin cancer deaths, although it accounts for less than 5% of all skin cancer cases; there were 70,230 new cases of melanoma in 2011: 40,010 in men and 30,220 in women. The incidence of malignant melanoma is rising at a rate faster than that of any other tumor; it has more than tripled among white persons between 1980 and 2011. Melanoma was responsible for 8790 total deaths in 2011: 5750 men and 3040 women. In 2011, the lifetime risk of developing melanoma (invasive and in situ) for all races was 2.76%; in white persons, the lifetime risk was 3.15%, and in African Americans, it was 0.11%. The incidence rates of melanoma have been increasing for the past 30 years. Since 1992, incidence rates among white individuals have increased by 2.8% per year in both men and women. The reasons for this are unclear, but excessive sun exposure is a major factor.

Early detection and treatment of malignant melanoma, as with most cancers, offers the best chance of a cure. Both basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma have a better than 99% cure rate if detected and treated early. Among patients with a superficial melanoma (<0.76 mm in depth), the survival rate is more than 99%, whereas among those with a larger lesion (>3.64 mm in depth), the 5-year survival rate is only 42% because these cancers are more likely to spread to other parts of the body. The external nature of melanoma gives the examiner an opportunity to detect these small, curable lesions.

The most important function of the skin is to protect the body from the environment. The skin has evolved in humans to be a relatively impermeable surface layer that prevents the loss of water, protects against external hazards, and insulates against thermal changes. It is also actively involved in the production of vitamin D. The skin appears to have the lowest water permeability of any naturally produced membrane. Its barrier to invasion retards potentially noxious agents from entering the body and causing internal damage. This barrier protects against many physical stresses and prohibits the invasion of microorganisms. By observing patients with extensive skin problems, such as burns, clinicians can appreciate the importance of this organ.

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

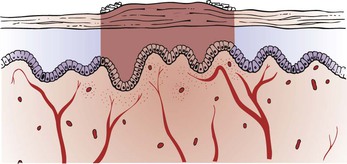

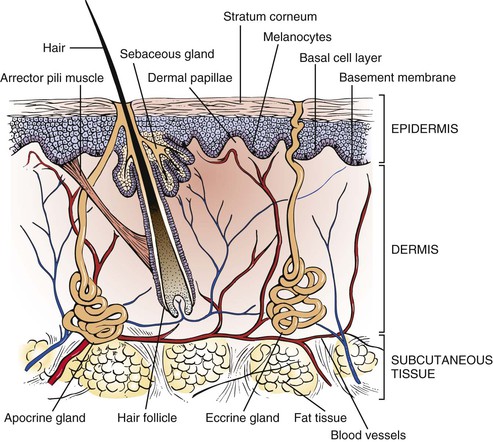

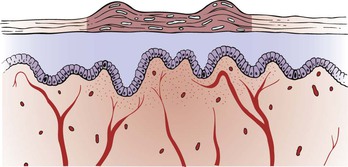

The three tissue layers of the skin, depicted in Figure 5-1, are as follows:

Figure 5–1 Cross section through the skin, illustrating the structures in the epidermis and subcutaneous tissues.

The epidermis is the thin, outermost layer of the skin. It is composed of several layers of keratocytes, or keratin-producing cells. Keratin is an insoluble protein that provides the skin with its protective properties. The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis and serves as a major physical barrier. The stratum corneum is composed of keratinized cells, which appear as dry, flattened, anuclear, and adherent flakes. The basal cell layer is the deepest layer of the epidermis and is a single row of rapidly proliferating cells that slowly migrate upward, keratinize, and are ultimately shed from the stratum corneum. The process of maturation, keratinization, and shedding takes approximately 4 weeks. The cells of the basal layer are intermingled with melanocytes, which produce melanin. The number of melanocytes is approximately equal in all people. Differences in skin color are related to the amount and type of melanin produced, as well as to its dispersion in the skin.

Beneath the epidermis is the dermis, which is the dense connective tissue stroma forming the bulk of the skin. The dermis is bound to the overlying epidermis by fingerlike projections that project upward into the corresponding recesses of the epidermis. In the dermis, blood vessels branch and form a rich capillary bed in the dermal papillae. The deeper layers of the dermis also contain the hair follicles with their associated muscles and cutaneous glands. The dermis is supplied with sensory and autonomic nerve fibers. The sensory nerves end either as free endings or as special end organs that mediate pressure, touch, and temperature. The autonomic nerves supply the arrector pili muscles, blood vessels, and sweat glands.

The third layer of the skin is the subcutaneous tissue, which is composed largely of fatty connective tissue. This highly variable adipose layer is a thermal regulator, as well as a protection for the more superficial skin layers from bone prominences.

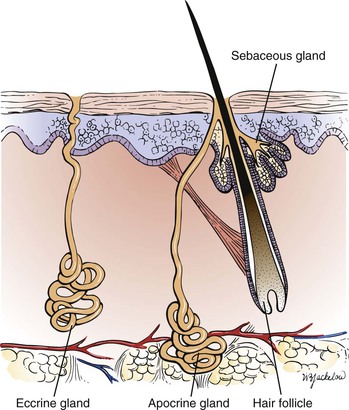

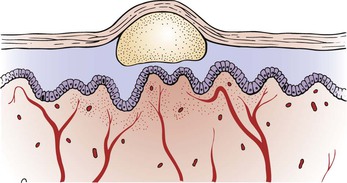

The sweat glands, hair follicles, and nails are termed skin appendages. The evaporation of water from the skin by the sweat glands provides a thermoregulatory mechanism for heat loss. Figure 5-2 illustrates the types of sweat glands.

Figure 5–2 Types of sweat glands.

Within the skin, there are 2 to 3 million small, coiled eccrine glands. The eccrine glands are distributed over the body surface and are particularly profuse on the forehead, axillae, palms, and soles. They are absent in the nail beds and in some mucosal surfaces. These glands are capable of producing more than 6 L of watery sweat in 1 day. The eccrine glands are controlled by the sympathetic nervous system.

The apocrine glands are larger than the eccrine glands. The apocrine glands are found in close association with hair follicles but tend to be much more limited in distribution than are the eccrine glands. The apocrine glands occur mostly in the axillae, the areolae, the pubis, and the perineum. They reach maturity only at puberty, secreting a milky, sticky substance. Apocrine glands are adrenergically mediated and appear to be stimulated by stress.

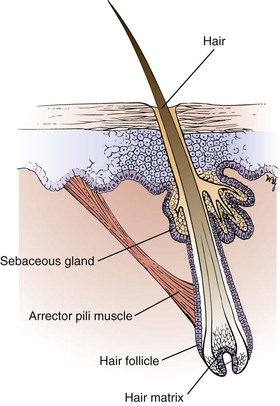

The sebaceous glands are also found surrounding hair follicles. The sebaceous glands are distributed over the entire body; the largest glands are found on the face and upper back. They are absent on the palms and soles. Their secretory product, sebum, is discharged directly into the lumen of the hair follicle, where it lubricates the hair shaft and spreads to the skin surface. Sebum consists of sebaceous cells and lipids. The production of sebum depends on gland size, which is directly influenced by androgen secretion.

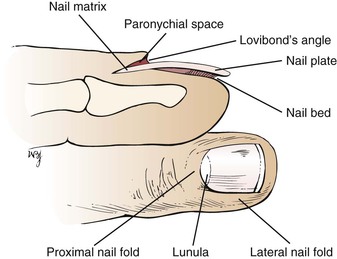

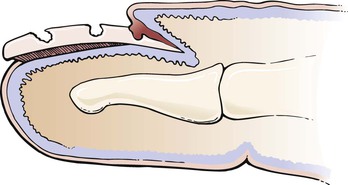

Nails protect the tips of the fingers and toes against trauma. They are derived by keratinization of cells from the nail matrix, which is located at the proximal end of the nail plate. The nail plate consists of the nail root embedded in the posterior nail fold, a fixed middle portion, and a distal free edge. The whitish nail matrix of proliferating epithelial cells grows in a semilunar pattern. It extends outward past the posterior nail fold and is called the lunula. The structural relationships of the nail are shown in Figure 5-3.

A hair shaft is a keratinized structure that grows out of the hair follicle. Its lower end, called the hair matrix, consists of actively proliferating epithelial cells. The cells at this end of the follicle, along with those of the bone marrow and gut epithelium, are the most rapidly growing dividing cells in the human body. This is the reason that chemotherapy causes hair loss, along with anemia, nausea, and vomiting. Visible hair is present over the entire body surface except on the palms, soles, lips, eyelids, glans penis, and labia minora. In apparently hairless areas, the hair follicles are small, and the shafts produced are microscopic. Hair follicles show conspicuous morphologic and functional heterogeneity. Follicles and their developing shafts differ from location to location in shaft length, color, thickness, curl, and androgen sensitivity. Some follicles, those in the axilla and inguinal areas, are very sensitive to androgens, whereas others in the eyebrow are insensitive. The arrector pili muscles attach to the follicle below the opening of the sebaceous gland. Contraction of this muscle erects the hair and causes “goose bumps.” The structure of a hair follicle is shown in Figure 5-4.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The main symptoms of disease of the skin, hair, and nails are the following:

Rash or Skin Lesion

There are some important points to clarify when a patient is interviewed about a new rash or skin lesion. The specific time of onset and location of the rash or skin lesion are critical. A careful description of the first lesions and any changes is vital. The patient with a rash or skin lesion should be asked the following questions:

“Was the rash initially flat? Raised? Blistered?”

“Did the rash change in character with time?”

“Have there been new areas involved since the rash began?”

“Is the lesion tender or numb?”

“What makes the rash better? Worse?”

“Was the rash initiated by sunlight?”

“Is the rash aggravated by sunlight?”

“What kind of treatment have you tried?”

“Do you have any joint pains? Fever? Fatigue?”

“Does anyone near you have a similar rash?”

“Have you traveled recently?” If so, “To where?”

“Have you had any contact with anyone who has had a similar rash?”

“Is there a history of allergy?” If so, “What are your symptoms?”

Note whether the patient has used any medications that may have changed the nature of the skin disorder.

Inquire whether the patient uses any prescription medications or over-the-counter drugs. Ask specifically about aspirin and aspirin-containing products. Patients can suddenly develop a reaction to medications that they have taken for many years. Do not ignore a long-standing prescription. Has the patient had any recent injections or taken any new medications? Does the patient use “recreational” drugs? Ask the patient about the use of soaps, deodorants, cosmetics, and colognes. Has the patient changed any of these items recently?

A family history of similar skin disorders should be noted. The effect of heat, cold, and sunlight on the skin problem is important. Could there be any contributing factor, such as occupation, specific food allergies, alcohol, or menses? Is there a history of gardening or household repair work? Has there been any contact with animals recently? The interviewer should also remember to inquire about psychogenic factors that may contribute to a skin disorder.

Determine the patient’s occupation, if it is not already known. Ascertain avocational and recreational activities. This information is important even if the patient has been exposed to chemicals or similar agents for years. Manufacturers frequently change the basic constituents without notifying the consumer. It may also take years for a patient to become sensitized to a substance.

Changes in Skin Color

Patients may complain of a generalized change in skin color as the first manifestation of an illness. Cyanosis and jaundice are examples of this type of problem. Determine whether the patient is aware of any chronic disease that may be responsible for these changes. Localized skin color changes may be related to aging or to neoplastic changes. Certain medications can also be responsible for skin color changes. Inquire whether the patient is taking or has recently taken any medications.

Pruritus

Pruritus, or itching, may be a symptom of a generalized skin disorder or an internal illness. Ask any patient with pruritus the following questions:

“When did you first notice the itching?”

“Did the itching begin suddenly?”

“Is the itching associated with any rash or lesion on your body?”

“Are you taking any medications?”

“Has there been any change in the sweating or dryness of your skin?”

Diffuse pruritus is observed in biliary cirrhosis and in cancer, especially lymphoma. Pruritus in association with a diffuse rash may be dermatitis herpetiformis. Determine whether the pruritus has been associated with a change in perspiration or dryness of the skin because either of these conditions may be the cause of the pruritus.

Changes in Hair

Inquire whether there has been a loss of hair or an increase in hair. Ascertain any changes in distribution or texture. If there have been changes, ask the following questions:

“When did you first notice the changes?”

“Did the change occur suddenly?”

“Has the change been associated with itching? Fever? Recent stress?”

“Are you aware of any exposure to any toxins? Commercial hair compounds?”

Changes in diet and medications are frequently responsible for changes in hair patterns. Hypothyroidism is frequently associated with loss of the lateral third of the eyebrows. Vascular disease in the legs often causes hair loss on the legs. Alternatively, ovarian and adrenal tumors can cause an increase in body hair.

Changes in Nails

Changes in nails may include splitting, discoloration, ridging, thickening, or separation from the nail bed. Ask the patient the following questions:

“When did you first notice the nail changes?”

“Have you had any acute illness recently?”

“Do you have any chronic illness?”

Fungal disease causes thickening of the nail. Clues to systemic disease may be found by close examination of the proximal nail fold, the lunula, the nail bed, the nail plate, and the hyponychium. Acute illnesses are associated with lines and ridges in the nail bed and nail. Medications and chemicals are notorious for causing nail changes.

General Suggestions

All patients should be asked whether there have been any changes in moles, birthmarks, or spots on the body. Determine any color changes, irregular growth, pain, scaling, or bleeding. Any recent growth of a flat, pigmented lesion is relevant information.

All patients should be asked whether there are any red, scaly, or crusted areas of skin that do not heal. Has the patient ever had skin cancer? If the patient has had skin cancer, further questioning regarding the body location, treatment, and description is appropriate.

Effect of Skin Disease on the Patient

Diseases of the skin play a profound role in the way the affected patient interacts socially. If located on visible skin surfaces, long-standing skin diseases may actually interfere with the emotional and psychological development of the individual. The attitude of a person toward self and others may be markedly affected. Loss of self-esteem is common. The adult with a skin disorder often faces limitation of sexual activity. This disruption of intimacy can foster or increase hostility and anxiety in the patient. Skin is a sensitive marker of an individual’s emotions. It is known that blushing can reflect embarrassment, sweating can indicate anxiety, and pallor or “goose bump” skin may be associated with fear.

Patients with rashes have always evoked feelings of revulsion. Rashes have been associated with impurity and evil. Even today, friends and family may reject the individual with a skin disease. Patients with skin that is red, oozing, discolored, or peeling are rejected not only by family members but perhaps even by their physicians. At other times, skin lesions cause others to stare at the patient, which causes further discomfort. Some skin disorders may be associated with such extreme physical or emotional pain that marked depression may result and, on occasion, lead to suicide.

Skin diseases are often treated palliatively. Because numerous skin disorders have no cure, many patients go through life helpless and frustrated, as do their physicians.

The role of anxiety as a natural stressor in producing rashes is frequently observed. Stress tends to worsen certain skin disorders, such as eczema. This creates a vicious cycle, because the rash then exacerbates the anxiety. Rashes are common symptoms and signs of psychosomatic disorders.

Clinicians should discuss these anxieties with the patient in an attempt to break the cycle. The interviewer who tries to elicit the patient’s feelings about the disease allows the patient to “open up.” The fears and fantasies can then be discussed. The examiner should also be comfortable in touching the patient for reassurance. This tends to improve the doctor-patient relationship because the patient has a lesser sense of isolation.

Physical Examination

The only equipment necessary for the examination of the skin is a penlight. The examination of the skin consists of only two steps:

The examination of the skin depends on inspection, but palpation of a skin lesion must also be performed. Although most skin lesions are not contagious, it is prudent to wear gloves to evaluate any skin lesion. This is especially true because of the prevalence of skin disease associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Palpation of a lesion helps define its characteristics: texture, consistency, fluid, edema in the adjacent area, tenderness, and blanching.

The patient and the examiner must be comfortable during the examination of the skin. The lighting should be adjusted to produce the optimal illumination. Natural light is preferable. Even in the absence of complaints related to the skin, a careful examination of the skin must be performed on all patients because the skin may provide subtle clues of an underlying systemic illness. Examination of the skin may be performed as a separate system approach, or, preferably, the skin should be examined when the other parts of the body are evaluated.

General Principles

The examiner should be suspicious of any lesion that the patient describes as having increased in size or changed in color. The development of any new growth warrants attention.

When examining the skin, the clinician initially determines the general aspects of the skin: the color, moisture, turgor, and texture of the skin.

Any color changes, such as cyanosis, jaundice, or pigmentary abnormalities, should be noted.

Red vascular lesions may be either extravasated blood into the skin, known as petechiae or purpura, or malformed elements of the vascular tree, known as angiomas. When pressure is applied by a glass slide over an angioma, it blanches. This is a useful test to differentiate an angioma from petechiae, which do not change when pressure from a glass slide is applied.

Asymmetry means that half the lesion appears different from the other half. Border irregularity describes a scalloped or poorly circumscribed contour. The color variation refers to shades of tan and brown, black, and sometimes white, red, or blue. A diameter larger than 6 mm, which is the size of a pencil eraser, is considered a danger sign for melanoma. A lesion that is evolving needs always to be evaluated.

The clinician should remember this axiom in dermatology: “There are more errors made by not looking than by not knowing.”

Excessive moisture may be seen in normal individuals, or it may be associated with fevers, emotions, neoplastic diseases, or hyperthyroidism. Dryness is a normal aging change, but it may also be seen in myxedema, nephritis, and certain drug-induced states. Look for excoriations, which might indicate the presence of pruritus as a clue to an underlying systemic illness.

When palpating the skin, evaluate its turgor and texture. Tissue turgor provides a mechanism for estimating the patient’s general state of hydration. If the skin over the forehead is pulled up and released, it should promptly reassume its normal contour. In a patient with decreased hydration, this response is delayed.

It is often difficult for the inexperienced examiner to evaluate the texture of the skin because texture is a qualitative parameter. Softness has occasionally been likened to the texture of skin over a baby’s abdomen. “Soft”-textured skin is seen in secondary hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, and eunuchoid states. “Hard”-textured skin is associated with scleroderma, myxedema, and amyloidosis. “Velvety” skin is associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Examination with Patient Seated

When the patient is seated, examine the hair and the skin on the hands and upper extremities.

Inspect the Hair

The hair and scalp are evaluated for any lesions. Is alopecia or hirsutism present? Pay attention to the pattern of distribution and texture of hair over the body. In certain diseases, such as hypothyroidism, the hair becomes sparse and coarse. In contrast, patients with hyperthyroidism have hair that is very fine in texture. Loss of hair occurs in many conditions: anemia, heavy metal poisoning, hypopituitarism, and some nutritional disease states, such as pellagra. Increased hair patterns are seen in Cushing’s disease, Stein-Leventhal syndrome, and several neoplastic conditions, such as tumors of the adrenal glands and gonads.

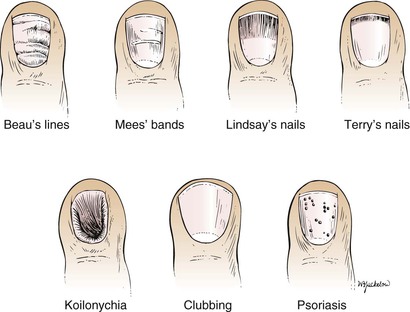

Inspect the Nail Beds

Evaluation of the nails can provide important clues about diseases. The nails may be affected in many systemic and dermatologic conditions. Nail-bed changes are usually not pathognomonic for a specific disease. Disorders stemming from renal, hematopoietic, or hepatic conditions may be evident from the nails. The nails should be inspected for shape, size, color, brittleness, hemorrhages underneath, transverse lines or grooves in the nail or nail bed, and an increased white area of the nail bed. Figure 5-5 illustrates some typical nail changes associated with medical diseases.

Beau’s lines are transverse grooves or depressions parallel to the lunula. Any severe, systemic illness that disrupts nail growth can produce Beau’s lines. They are often associated with infections (typhus, acute rheumatic fever, malaria, acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS]), nutritional disorders (protein deficiency, pellagra), circulatory problems (myocardial infarction, Raynaud’s disease), dysmetabolic states (diabetes, hypothyroidism, hypocalcemia), digestive diseases (diarrhea, enterocolitis, chronic pancreatitis, sprue), drugs (chemotherapy agents), operations, and alcoholism. Beau’s lines are caused by conditions that cause the nail to grow slowly or even cease to grow for short intervals. The point of arrested growth is seen as a transverse groove in the nail. These lines are most commonly seen in the thumbnails and toenails. Figure 5-6A shows a patient’s fingers with Beau’s lines on the nails. Figure 5-6B shows Beau’s lines in the toenails of a patient who underwent major surgery 5 months earlier.

Figure 5–6 Beau’s lines. A, Fingernails. B, Toenails.

On occasion, a white transverse line or band results from poisoning or an acute systemic illness. These lines, called Mees’ bands, are historically associated with chronic arsenic poisoning. They are also seen in patients with Hodgkin’s disease, congestive heart failure, leprosy, malaria, chemotherapy, carbon monoxide poisoning, and other systemic insults. These lines or bands are also parallel to the lunula. By measuring the width of the line and approximating nail growth at 1 mm per week, the examiner may be able to determine the duration of the antecedent acute illness. Figure 5-7 shows the fingernails of a patient who received chemotherapy several weeks earlier.

Figure 5–7 Mees’ bands.

Lindsay’s nails are also called “half-and-half nails.” The proximal portion of the nail bed is whitish, whereas the distal part is red or pink. Chronic renal disease and azotemia are the commonly associated conditions with this type of nail abnormality. Figure 5-8 shows Lindsay’s nails secondary to chronic renal failure.

Figure 5–8 Lindsay’s nails.

Terry’s nails are white nail beds to within 1 to 2 mm of the distal border of the nail. These nail findings are most commonly associated with hepatic failure, cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia, chronic congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, malnutrition, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Figure 5-9 shows classic Terry’s nails.

Figure 5–9 Terry’s nails.

Splinter hemorrhages are formed by extravasation of blood from longitudinal nail bed blood vessels into adjacent troughs. Splinter hemorrhages are very common. It has been estimated that up to 20% of all hospitalized patients have splinter hemorrhages. Their presence is most often related to local, light trauma, but these hemorrhages are commonly associated with systemic disease. Classically associated with subacute bacterial endocarditis, splinter hemorrhages may also be seen in leukemia, vasculitis, infection, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, renal disease, liver disease, and diabetes mellitus, among other diseases. Splinter hemorrhages are depicted in Figure 5-10.

Figure 5–10 Splinter hemorrhages.

Is koilonychia present? Koilonychia, or “spoon nail,” is a dystrophic state in which the nail plate thins and a cuplike depression develops. Spoon nails are most commonly associated with iron-deficiency anemia but may be seen in association with thinning of the nail plate from any cause, including local irritants. Figure 5-11 shows a normal fingernail in comparison with koilonychia secondary to iron-deficiency anemia.

Figure 5–11 Koilonychia.

Inspect the Nails for Clubbing

The angle between the normal nail base and finger is approximately 160 degrees, and the nail bed is firm. The angle is referred to as Lovibond’s angle. When clubbing develops, this angle straightens out to greater than 180 degrees, and the nail bed, when palpated, becomes spongy or floating. As clubbing progresses, the base of the nail becomes swollen, and Lovibond’s angle greatly exceeds 180 degrees. The nail has a bullous shape with exaggerated longitudinal and horizontal curvatures. A fusiform enlargement of the distal digit may also occur. In Figure 5-12, a normal finger is compared with a finger with nail clubbing.

Figure 5–12 Late-stage clubbing.

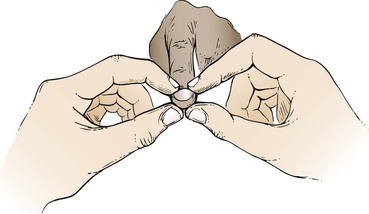

To examine for clubbing, the patient’s finger is placed on the pulp of the examiner’s thumbs, and the base of the nail bed is palpated by the examiner’s index fingers. If clubbing is present, the nail appears to float on the finger. Figure 5-13 illustrates the technique for assessing whether early clubbing is present.

Since Hippocrates first described digital clubbing in patients with empyema, digital clubbing has been associated with various underlying pulmonary, cardiovascular, neoplastic, infectious, hepatobiliary, mediastinal, endocrine, and gastrointestinal diseases. Clubbing of the nails is most commonly acquired but may be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. When not inherited as a familial trait, clubbing is most commonly seen associated with congenital cyanotic heart disease, cystic fibrosis, mesothelioma of the pleura, and pulmonary neoplasms. The most common acquired pulmonary cause is bronchogenic carcinoma; it is mainly seen in non–small-cell cancer (54% of all cases), and not generally seen in small-cell lung cancer (<5% of cases). In a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who manifests clubbing, other causes, including bronchiectasis or bronchogenic carcinoma, should be sought. Clubbing is also found in suppurative lung disease: lung abscess, empyema, bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis. The initial manifestation of clubbing is a softening of the tissue over the proximal nail fold.

Inspect the Nails for Pitting

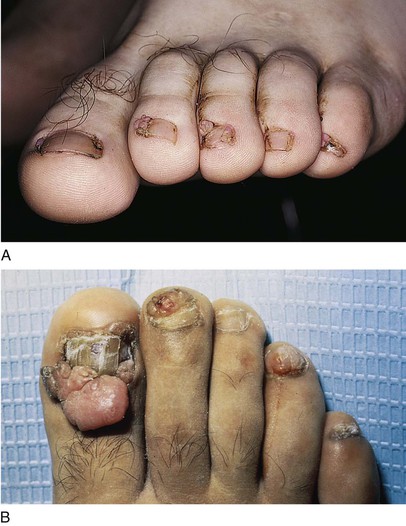

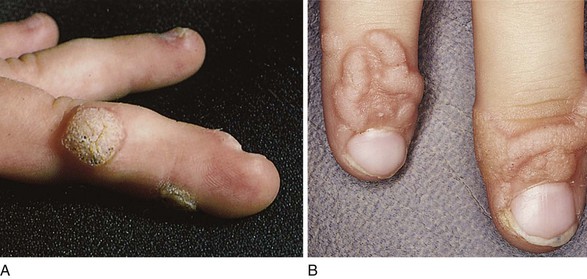

Pitting of the nails is commonly associated with psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy. Involvement of the nail bed and nail matrix by psoriasis causes the nail plate to be thickened and pitted. Nail involvement occurs in approximately 50% of all patients with psoriasis. Multiple pits in the nail are produced by discrete psoriatic foci in the nail matrix. Minor degrees of pitting are also seen in persons with no other skin complaints. Pitting rarely occurs in toenails. Psoriatic nail pitting is shown in Figure 5-14; Figure 5-15 illustrates a cross section of pitting. Figure 5-16A shows psoriatic nail lesions in another patient. Notice the characteristically dystrophic nail changes caused by subungual hyperkeratosis. Figure 5-16B is a close-up of a typical nail with psoriatic changes.

Figure 5–14 Psoriasis: nail pitting.

Figure 5–15 Cross section of nail pitting.

Figure 5–16 A and B, Psoriatic nail lesions.

Inspect the Skin of the Face and Neck

Evaluate the eyelids, forehead, ears, nose, and lips carefully. Evaluate the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose for ulceration, bleeding, or telangiectasis. Is the skin at the nasolabial fold and mouth normal?

Inspect the Skin of the Back

Examine the skin of the patient’s back. Are any lesions present?

Examination with Patient Lying Down

Inspect the Skin of the Chest, Abdomen, and Lower Extremities

Ask the patient to lie down so that you can complete the examination of the skin. Inspect the skin of the chest and abdomen. Pay particular attention to the skin of the inguinal and genital area. Inspect the pubic hair. Elevate the scrotum. Inspect the perineal area. Evaluate the pretibial areas for the presence of ulcerations or waxy deposits.

Examine the feet and soles carefully for any skin changes. Spread the toes to evaluate the webs between them thoroughly.

Ask the patient to roll onto the left side so that you may examine the skin on the back, gluteal, and perianal areas.

Description of Lesions

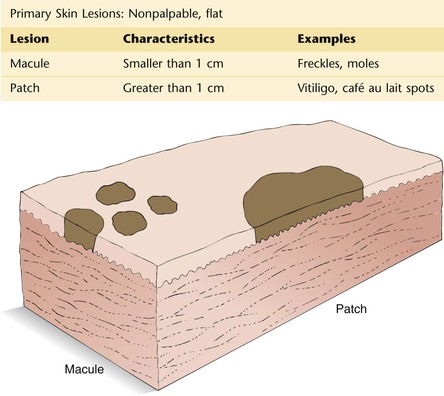

If a skin lesion is found, it should be classified as a primary or secondary lesion, and its shape and distribution should be described. Primary lesions arise from normal skin. They result from anatomic changes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutaneous tissue. The primary lesion is the most characteristic lesion of the skin disorder. Secondary lesions result from changes in the primary lesion. They develop during the course of the cutaneous disease.

The first step in identifying a skin disorder is to characterize the appearance of the primary lesion. In the description of the skin lesion, the clinician should note whether the lesion is flat or raised and whether it is solid or contains fluid. A penlight is often useful to determine whether the lesion is slightly elevated. If a penlight is directed to one side of a lesion, a shadow forms according to the height of the lesion.

The location of the lesion on the body is important. Therefore the distribution of the eruption is crucial in making a diagnosis. It may be rewarding to inspect a patient’s clothing when contact dermatitis or pediculosis (infestation with lice) is suspected. On occasion, occupational exposure may leave traces of contamination with oils or other materials that may be visible on the clothing and help in the assessment.

The three specific criteria for a dermatologic diagnosis are based on morphologic characteristics, configuration, and distribution, morphologic characteristics being the most important. The purpose of the following section is to acquaint the reader with the morphologic features of the primary and secondary lesions and the vocabulary associated with them.

Primary and Secondary Lesions

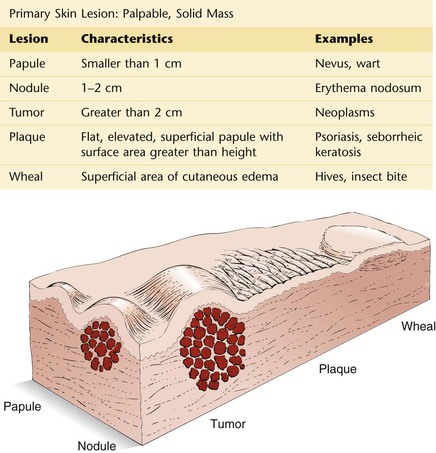

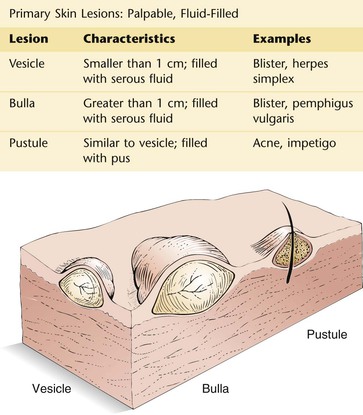

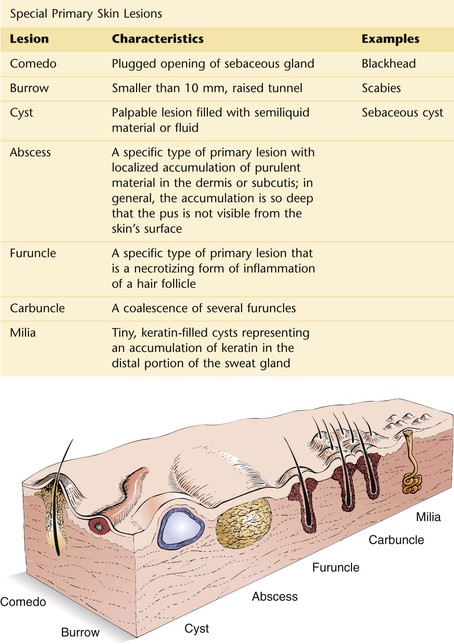

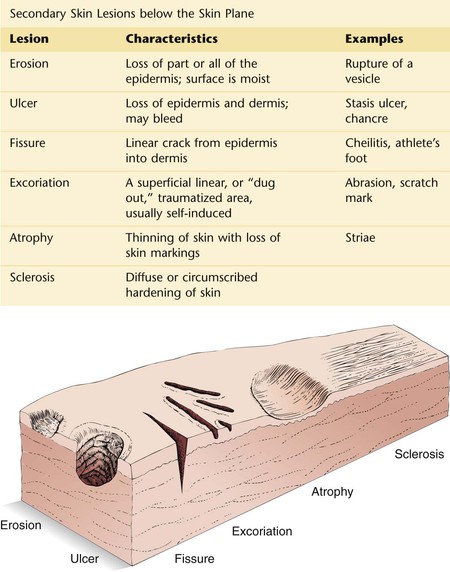

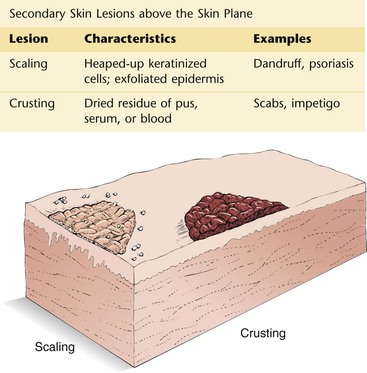

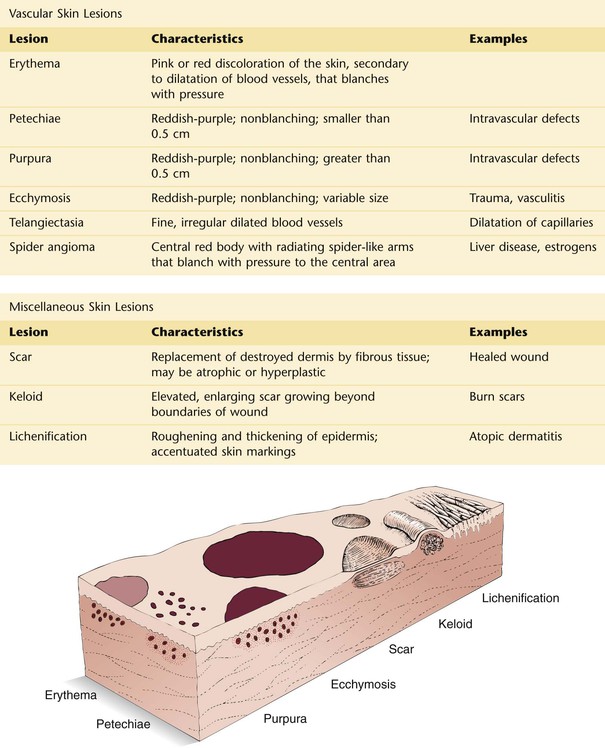

To facilitate reading, the primary lesions are listed here with regard to being flat or elevated and solid or fluid filled (Figs. 5-17 to 5-20). There is no “standard” size of a primary lesion. The dimensions indicated are only approximate. The secondary lesions are grouped according to their occurrence below or above the plane of the skin (Figs. 5-21 and 5-22). Other important lesions are shown and described in Figure 5-23.

Figure 5–17

Figure 5–18

Figure 5–19

Figure 5–20

Figure 5–21

Figure 5–22

Figure 5–23

Configuration of Skin Lesions

It is not essential for the examiner to make a definitive diagnosis of all skin disease. A careful description of the lesion, the pattern of distribution, and the arrangement of the lesion often points to a group of related disease states with similar manifesting dermatologic signs (e.g., confluent macular rashes, bullous diseases, grouped vesicles, papular rashes on an erythematous base). For example, grouped urticarial lesions with a central depression are suggestive of insect bites. Figure 5-24 lists the terms used to describe the configurations of lesions.

Figure 5–24

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Skin disorders are frequently perplexing to the examiner. When an examiner sees a rash, the common thought is “Where do I begin?” All too often, the examiner may become frustrated and not even attempt to make a diagnosis. Dermatologic terms are complicated, and the names of dermatologic disorders may be intimidating. Often the descriptions of skin disorders in textbooks are more confusing than helpful.

There are more than 2500 separately named dermatologic diagnoses. Most of these diseases occur in low frequencies; only 10 to 15 common conditions constitute approximately 50% of all dermatologic diagnoses. If the 50 most common conditions were considered, a diagnosis could be rendered for more than 95% of all patients.

In approaching a skin lesion, the examiner must do the following:

First, identify the primary lesion.

Second, identify its distribution.

Skin diseases evolve and their manifestations change. A lesion may evolve from a blister to an erosion, from a vesicle to a pustule, or from a papule to a nodule or tumor.

There are many common skin disorders or lesions with which the examiner should be familiar. Illustrated in the figures in this chapter are examples of some of these conditions; these cross-sectional diagrams illustrate the locations of these abnormalities in the skin and the involvement of the various skin layers in the pathogenesis of the conditions. The text describes the primary lesions.

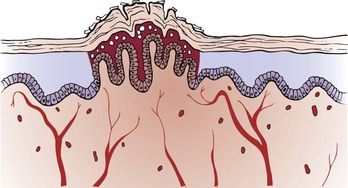

A common wart is a common, benign growth usually caused by an infection of an epidermal cell by the human papillomavirus (HPV). There are more than 100 types of HPV, and different types of the virus cause different types of warts. Most types of HPV cause relatively harmless conditions such as common warts, whereas others may cause serious disease such as cancer of the cervix. Wart viruses pass from person to person. Individuals can be infected by the virus indirectly by touching a towel or object used by someone who has the virus. Each person’s immune system responds differently to HPV, so not everyone who comes in contact with HPV will develop warts. Warts are firm nodules with rough, keratinous surfaces that range in size from pinhead to pea size and can coalesce to form an extensive bed. There is vacuolation of the epidermis with scaling and an upward growth of the dermal papilla. Figure 5-25 illustrates a cross section through a wart. Two examples of finger warts are pictured in Figure 5-26.

Figure 5–26 A and B, Warts.

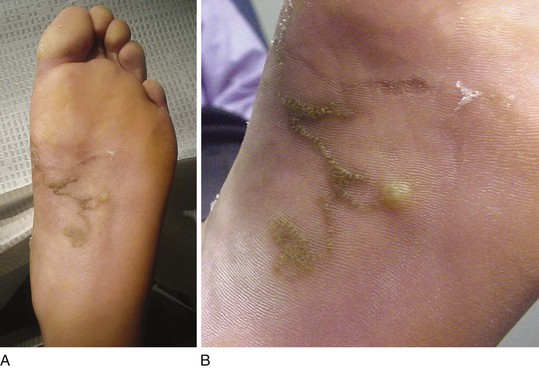

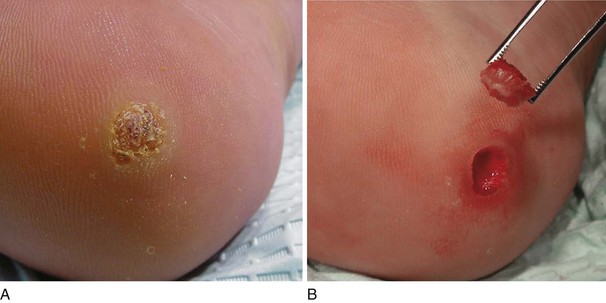

Warts can also occur on the soles of the feet (plantar verruca), where they have a distinctive appearance because of constant pressure. They are very painful owing to the constant pressure, which forces the keratinous material into the deeper tissue. An example of a plantar wart on the heel is shown in Figure 5-27A. Notice the keratotic lesion with a yellow center, within which are visible areas of multiple red to black dots that represent hemorrhage from the tips of the dermal papillae. Classically, there is interruption of the normal skin lines as well. Figure 5-27B shows the excised lesion. Notice the depth of the lesion when viewed horizontally. Because warts are in the epidermis, excision just to the level of the dermis is sufficient for complete removal with minimal to no scarring.

Figure 5–27 Plantar wart. A, Note the keratotic lesion with the yellow center and areas of hemorrhage within. B, After excision.

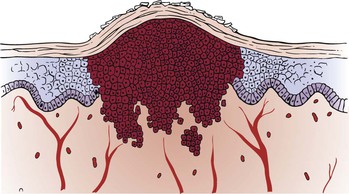

A squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm of keratocytes in the epidermis and is locally invasive into the dermis. The tumor results in a scaling, crusting nodule or plaque that can ulcerate and bleed. Squamous cell carcinoma is a potentially dangerous lesion that can infiltrate the surrounding structures and metastasize to lymph nodes and other organs. The causes include ultraviolet radiation, x-radiation, polycyclic hydrocarbons (e.g., tar, mineral oils, pitch, and soot), mucosal diseases (e.g., lichen planus and Bowen’s disease), scars, chronic skin disorders, genetic diseases (e.g., albinism and xeroderma pigmentosum), and human papillomavirus. The tumor develops predominantly on areas of skin exposed to sunlight. The latency from carcinogenic exposure to the development of the tumor may be as long as 25 to 30 years. Two examples of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin are pictured in Figure 5-28. Notice that the lesions are ulcerated with firm, raised indurated margins. Figure 8-11 also shows a patient with a squamous cell carcinoma and a malignant melanoma of the ear lobule. A squamous cell carcinoma on the lip of another patient is pictured in Figure 5-29. Notice the round, centrally ulcerating tumor. Figure 5-30 illustrates a cross section through a squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 5–29 Squamous cell carcinoma of lip.

Although squamous cell carcinomas are usually found in sun-exposed areas, the lesion pictured in Figure 5-31 is on the plantar aspect of the foot. A callus is also present under the head of the first metatarsal.

A basal cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm of the basal cells of the epidermis and is the most common skin malignancy. The epidermis is thickened, and the dermis may be invaded by the malignant basal cells. It may manifest as a lesion with a pearly, rolled, well-defined margin and a central ulcerated depression. Although sunlight is an important etiologic factor, basal cell carcinomas are almost always seen on the face and rarely in other sun-exposed areas. They are slow-growing tumors and rarely metastasize, in contrast to squamous cell carcinomas. They are locally invasive, and when located near the eye or nose, they may invade the cranial cavity. If ulceration, bleeding, and crusting occur, a rodent ulcer is said to be present. Any nonhealing lesion should be carefully evaluated for the possibility of a basal cell carcinoma. Figures 5-32 to 5-34 illustrate the typical features of a basal cell carcinoma.

Figure 5–32 Cross section through a basal cell carcinoma.

Figure 5–33 Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer).

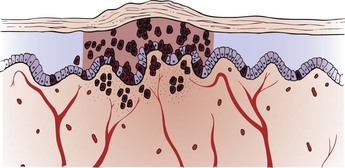

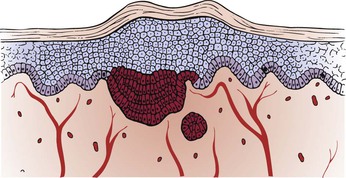

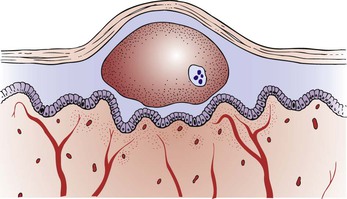

A melanoma is a malignant neoplasm of the melanocytes of the epidermis. If untreated or unrecognized, a melanoma progresses to fatal metastases. Most melanomas have a prolonged superficial, or horizontal, growth phase in which there is a progressive lateral expansion. With time, the melanoma enters the vertical, or deep, phase by penetrating into the dermis, and metastatic spread may occur.

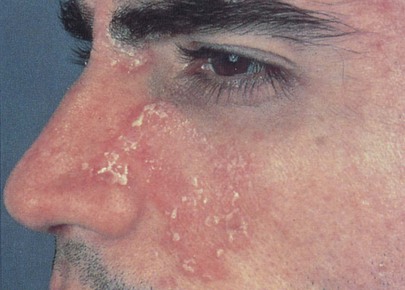

Malignant melanomas are the most common malignancy seen by dermatologists. The incidence of malignant melanoma is increasing faster than that of any other form of malignancy. Most melanomas have atypical pigmentation in the epidermis, such as shades of red, white, gray, blue, brown, and black, all in a single lesion. There are four types of malignant melanoma: lentigo maligna melanoma, superficial spreading melanoma, nodular malignant melanoma, and acral-lentiginous malignant melanoma. Figure 5-35 shows the typical features of a lentigo maligna melanoma on the face. The lentigo maligna melanoma is seen frequently in the geriatric population. This type of melanoma has a prolonged horizontal growth phase and appears in areas of sun-exposed, sun-damaged skin. The superficial spreading variety (Fig. 5-36) is the most common type of melanoma (70% of all melanomas). Typically, an irregularly colored plaque has sharp notches and variegation of pigment. If it is diagnosed early, the prognosis is excellent, with a 5-year survival rate of 95%. Figure 5-37 illustrates a cross section through a melanoma. Vertical growth and deep invasion follow the spreading phase of superficial malignant melanomas. Figure 5-38 shows another superficial spreading melanoma that has developed vertical growth. The nodular melanoma is the second most common type, seen in approximately 15% of cases of melanoma. Unlike the superficial spreading type, these melanomas are usually black, brown, or dark blue and tend to grow rapidly for months.

Figure 5–35 Lentigo maligna melanoma.

Figure 5–36 Superficial spreading malignant melanoma.

Melanomas occur predominantly in white individuals and have a predilection for the back in men and women and for the anterior tibial areas in women. In general, lesions on the back, axillae, neck, and scalp (the so-called BANS area) tend to have a worse prognosis than do melanomas on the extremities. A great contrast between the risk of acquiring melanoma and basal or squamous cell carcinoma is that basal and squamous cell carcinomas occur more frequently in individuals who are exposed to constant sunlight, such as sailors and agricultural workers. Melanomas occur more often in rather fair-skinned individuals who experience brief, intense sun exposure, such as that occurring during vacations in the southern latitudes.

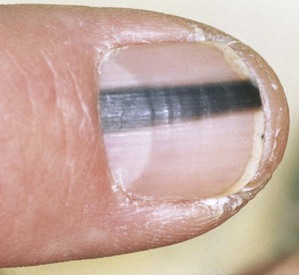

Fewer than 5% of all melanomas occur in the African-American population. The acral-lentiginous melanoma is the most common form of melanoma in African Americans and in Asians occurring on non–hair-bearing parts of the body: palms, soles, beneath the nails and in the oral mucosa. It is more common on toenails than on fingernails. Acral-lentiginous melanoma accounts for 29% to 72% of melanoma in dark-skinned individuals but less than 1% of melanoma in fair-skinned people. Unlike other forms of melanoma, acral-lentiginous melanomas do not appear to be linked to sun exposure. The average age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. However, the melanoma can occur also in white populations and in young people. These melanomas have a short superficial growth phase and an early vertical growth phase and, as such, are associated with a poor prognosis. Typical signs for an acral-lentiginous melanoma include:

• Longitudinal tan, black, or brown streak on a fingernail or toenail

• Pigmentation of proximal nail fold

• Areas of dark pigmentation on palms of hands or soles of feet

An acral-lentiginous melanoma on the sole of an African-American patient is pictured in Figure 5-39. The nail of the hallux (great toe) is a common site. The famous Jamaican (of African descent) singer-songwriter, musician, and revered performer of reggae music, Bob Marley, died at age 36 years of age from metastatic acral-lentiginous melanoma that originated in one of his toenails. Figure 5-40 shows an acral-lentiginous melanoma of the nail bed, with a wide longitudinal band and the variegated colors. Figure 5-41 shows another patient with an acral-lentiginous melanoma of the nail bed. Notice that the band width is slightly wider at the base than at the tip, indicating a rapidly growing lesion. Even though acral-lentiginous melanoma is rare, given its atypical locations and poor survival rates, it is important that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion in all ethnic groups and closely examine a patient’s palms, soles, and nail beds.

Figure 5–39 Acral-lentiginous melanoma.

Figure 5–40 Acral-lentiginous melanoma of the nail bed.

Figure 5–41 Melanoma of the nail bed.

Figure 5-42 shows a subungual presentation of malignant melanoma of the hallux. Unusual pigmentation under the nail, especially if of long duration, should always be regarded with suspicion. Subungual melanomas represent approximately 20% of melanomas in dark-skinned and Asian populations, in comparison with approximately 2% of cutaneous melanomas in white populations. Ultraviolet radiation exposure seems to be an important risk factor for cutaneous melanoma; however, because ultraviolet radiation is unlikely to penetrate the nail plate, it does not appear to be a risk factor for subungual melanomas. There is a considerable predominance of subungual melanoma localized on the thumb (58% of all affected fingers) and the hallux (86% of all affected toes).

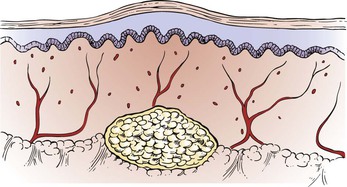

A lipoma is a benign growth of subcutaneous fat and has a rubbery appearance. Lipomas are found most often on the torso, neck, upper thighs, upper arms, and armpits, but they can occur almost anywhere in the body. One or more lipomas may be present at the same time. Lipomas are the most common noncancerous soft tissue growth. The epidermis is normal. Frequently, an encapsulated lipoma may grow to a very large size and elevate the overlying dermis and epidermis, as shown in Figure 5-43; a cross section through a lipoma is illustrated in Figure 5-44. The examiner can easily push into the soft tissue tumor. Another example of a lipoma is shown on the arm of the patient in Figure 5-45.

Figure 5–43 Lipoma of the back.

Figure 5–44 Cross section through a lipoma.

Figure 5–45 Lipoma of the arm.

Café-au-lait spots are patch lesions that are well circumscribed and brownish. They may occur as a solitary birthmark in up to 10% of the normal population. The café-au-lait macule or patch results from an increased number of functionally hyperactive melanocytes. Many healthy people have one or two small café-au-lait spots. However, adults who have six or more spots that are larger than 1.5 cm in diameter (0.5 cm in children) are likely to have neurofibromatosis. In most people with the condition, these spots may be the only symptom. Figure 5-46 shows a café-au-lait spot (patch) in a patient with neurofibromatosis.

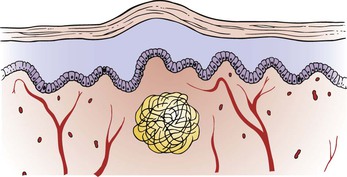

A neurofibroma is a tumor produced by a focal proliferation of neural tissue in the dermis. The epidermis is normal. Neurofibromas may appear as papules or nodules. Cutaneous neurofibromas are soft in consistency. Neurofibromatosis is a disorder in which multiple neurofibromas are present, sometimes as many as several hundred. Although the tumors are benign, the occurrence of these space-occupying lesions may produce severe disfigurement or neurologic disease. Other dermatologic features of neurofibromatosis include multiple café-au-lait patches and axillary freckling. Figure 5-47 shows several neurofibromas in a patient with neurofibromatosis; a cross-sectional view is illustrated in Figure 5-48. Figure 5-49 shows axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign) in a patient with neurofibromatosis. Figure 5-50 shows multiple neurofibromas on the face of another patient with neurofibromatosis.

Figure 5–48 Cross section through a neurofibroma. Note that the tumor is a well-delimited mass of loosely packed neural elements.

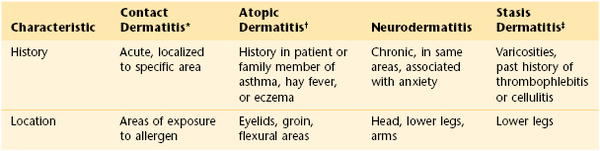

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory reaction of the skin that is precipitated by contact with an irritant or allergen, such as detergents, acids, alkali, plants, medicines, and solvents. Vesicles in the epidermis and perivascular inflammation result. Figure 5-51 shows contact dermatitis in reaction to poison ivy; the area is illustrated in cross section in Figure 5-52. The characteristic linear distribution of papules, vesicles, and bullae is visible on this patient’s calf where the leaves of the plant touched the leg. The distribution of the bullous lesions together with their location is strongly suggestive of the diagnosis, which was confirmed by biopsy.

Figure 5–51 Contact dermatitis: poison ivy reaction.

Figure 5–52 Cross section through an area of contact dermatitis. Note the perivascular inflammation in the dermis, as well as the vesicles and bullae in the epidermis.

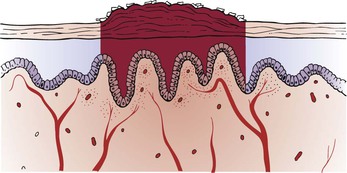

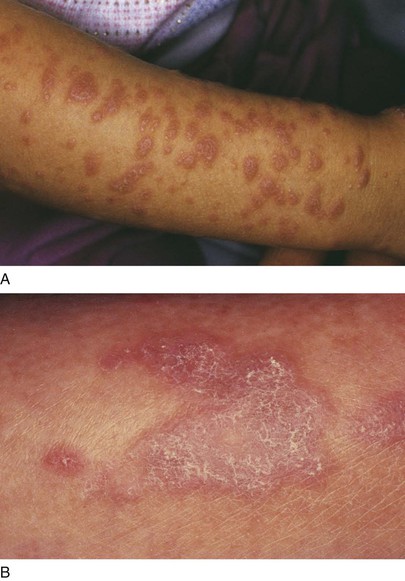

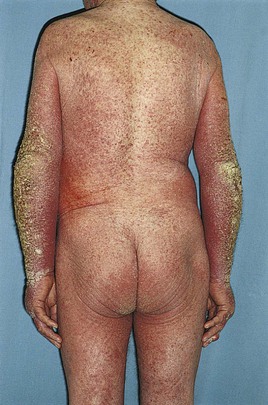

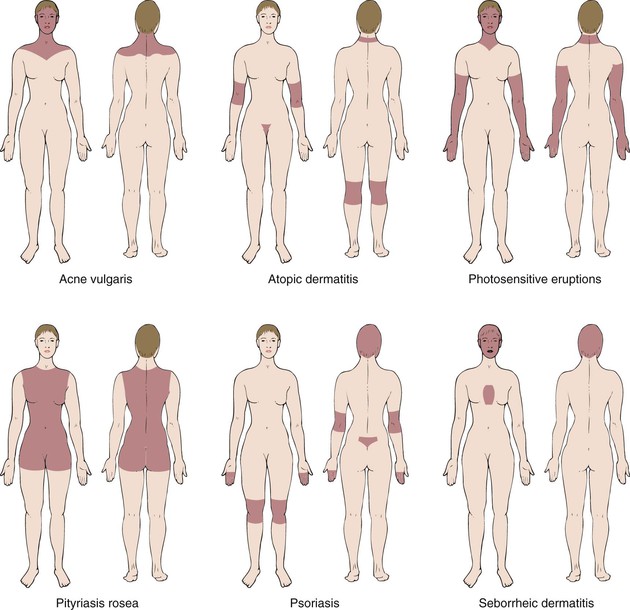

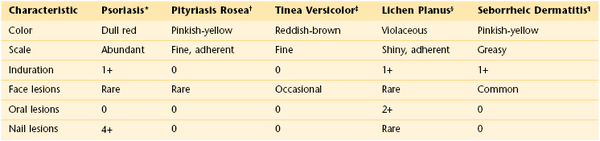

Psoriasis is one of the most common noninfectious skin disorders. It is frequently inherited and often chronic, and it, too, may affect the joints and nails. The rash is characterized by well-defined, slightly raised, hyperkeratotic (scaling) plaques. If the lesion is scratched, small bleeding points appear, which is a specific sign of the disease. The lesions are frequently symmetric and can be extremely itchy. The stratum corneum thickens, and erythematous plaques with silvery scales result. Within the dermis, there is capillary proliferation with perivascular inflammation. The lesions are characteristically located on the elbows, knees, scalp, and intergluteal cleft. Figure 5-53 shows the typical, symmetric lesions on the knees of an affected patient. Figure 5-54 shows the classic scaling lesions at the intergluteal cleft of another patient. Figure 5-55 illustrates a cross section through an area of psoriasis (see also Fig. 5-15). Figure 5-56 shows psoriasis of the scalp. The lesions commonly extend beyond the hair-bearing areas onto the adjacent skin. Surprisingly, this lesion rarely results in hair loss. Figure 5-57 shows severe, diffuse psoriasis involving more than 85% of the body of a 56-year-old man. This patient suffered from persistent itching, burning, and bleeding with psoriasis for more than 35 years. Psoriasis may produce several nail changes. Pitting of the nail has already been discussed (see Fig. 5-14). There are several other nail changes: oily patches, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages.

Figure 5–53 Psoriatic lesions on the knees.

Figure 5–54 Psoriatic lesions on the intergluteal cleft.

Figure 5–56 Psoriasis of the scalp.

Fungal infections of the skin, nails, and hair are very common. The main fungi responsible for skin, hair, and nail diseases are dermatophytes of the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton. Fungal infections of the skin produce a scaling, erythematous patch, often with a reddened, raised, serpiginous border. The term tinea indicates the fungal cause, and the second word denotes the area of the body involved: tinea corporis is infection on the torso; tinea pedis, in the foot; tinea faciale, in the face; tinea barbae, in the beard and moustache area in men; tinea cruris, in the groin; and tinea capitis, in the head. In all cases, the epidermis is thickened, and the stratum corneum is infiltrated with fungal hyphae. The underlying dermis displays mild inflammation. Tinea corporis is commonly known as “ringworm.” Figures 5-58 and 5-59 illustrate the classic annular lesion of tinea corporis with its raised erythematous border and central clearing. Another example of tinea corporis is pictured in Figure 5-60. Tinea faciale in a child is pictured in Figure 5-61. Tinea cruris is pictured in Figure 5-62. This common pruritic lesion is seen commonly in young men; it is unusual in women. It spreads outward from the groin, down the thigh, leaving postinflammatory pigmentation. The advancing border is well defined, red, scaly, and slightly raised. If untreated, the eruption can spread onto the lower abdomen, as shown, and the buttocks. The foot of a patient with tinea pedis is pictured in Figure 5-63. Notice the maceration with erosions and scaling.

Figure 5–58 Cross-section through an area of tinea corporis. Note the thickened stratum corneum, which is infiltrated by the fungus.

Figure 5–59 Tinea corporis.

Figure 5–60 Tinea corporis.

Figure 5–61 Tinea faciale.

Figure 5–62 Tinea cruris.

Figure 5–63 Tinea pedis.

Bacterial and fungal infections are common in diabetic patients. Figure 5-64 depicts bacterial cellulitis and tinea pedis in a diabetic patient. Tinea pedis produces macerated, scaling, fissured toe webs; inflammatory epidermis; and thick, hypertrophic, discolored nails.

Onychomycosis is an infection in which fungal organisms invade the nail bed and is the most common nail disorder. It accounts for nearly 50% of all nail problems. Its prevalence in the general population ranges from 2% to 14%. This infection causes progressive changes in the color, structure, and texture of the nail. It rarely resolves spontaneously, and, even with treatment, it may take months to years to clear. Figures 5-65 and 5-66 show examples of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis, the most common form of nail infection, caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Onychomycosis results in inflammation of the nail bed, which promotes hyperkeratosis of the nail bed epithelium and thickening. This may cause a lifting up of the nail plate, as shown in Figure 5-67.

Figure 5–65 Subungual onychomycosis.

Figure 5–66 Subungual onychomycosis.

Figure 5–67 Onychomycosis and lifting of the nail plate.

Pityriasis rosea is a common, acute, self-limiting inflammatory disease of unknown cause that usually occurs during the spring. The generalized eruption is preceded by a “herald patch,” which is a single lesion resembling that of tinea corporis. In several days, the generalized eruption appears. Papulosquamous plaques appear over the trunk and rarely on the face and distal extremities. Although patients may complain of mild itching, they feel quite well. The full-blown picture develops slowly over 5 to 10 days and lasts for approximately 3 to 6 weeks. Slight hyperkeratosis of the epidermis with moderate dermal perivascular infiltration occurs. Figure 5-68 shows a herald patch and the characteristic lesions of pityriasis rosea; Figure 5-69 illustrates a cross-sectional view. Notice the delicate scale at the border of the annular lesion. Secondary syphilis may manifest with a similar eruption. It is therefore important to order a serologic test for syphilis in any individual with pityriasis rosea.

Figure 5–68 Pityriasis rosea. Note the herald patch.

Herpes zoster, or shingles, is an intraepidermal vesicular eruption occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Bullae and multinucleated giant cells are present in the epidermis, with perivascular inflammation of the dermis. The condition is caused by activation of the varicella-zoster virus. Groups of vesicles and bullae on erythematous bases are present along the distribution of peripheral nerves. Severe pain often precedes the eruption. Figure 5-70 shows herpes zoster lesions along the T3 distribution in two patients. Usually, the distribution occurs along the spinal or cranial nerves, but it can become generalized, as pictured in Figure 5-71; Figure 5-72 illustrates a cross section. Figure 5-73 is a close-up photograph of the typical vesicles on an erythematous base in a dermatomal distribution.

Figure 5–71 Herpes zoster, generalized.

Figure 5–72 Cross section through one of the vesicles in herpes zoster. Note the large epidermal bullae with the classic multinuclear cells.

Figure 5–73 Herpes zoster vesicles.

Herpesvirus infections are frequently encountered in patients with HIV infection; approximately 25% to 50% of these patients have some form of herpetic disease during the course of their illness. Herpesvirus infections are thought to be predictive of future progression from HIV infection to AIDS; the rate of this association with progression is 23% at 2 years and up to 73% at 6 years. When CD4+ T cell counts fall to fewer than 100 cells/mm3, the likelihood of a herpesvirus infection approaches 95%. Herpes zoster infections may be severe and fulminant in immunocompromised patients, such as in the patient shown in Figure 7-62.

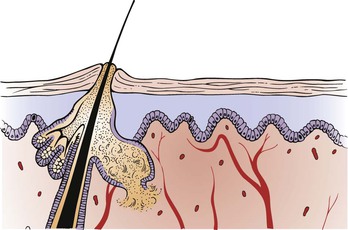

Acne is a pustular disease affecting the hair follicles and sebaceous glands. In this condition, pustules, papules, and comedones are the primary lesions. There are collections of intradermal and intrafollicular neutrophils. Within the dermis, the hair follicle is occluded by a collection of keratin, sebum, and inflammatory cells. The hair follicle often ruptures into the dermis as a result of increasing pressure, which leads to further dermal inflammation (Figs. 5-74 to 5-77).

Figure 5–74 Cross section through an area of acne. Note the rupturing of the sebaceous gland in the dermis as a result of a plugged hair follicle, which results in dermal inflammation.

Figure 5–75 Acne.

Figure 5–76 Acne.

Figure 5–77 Acne.

Tinea versicolor is a common superficial, noninflammatory, noncontagious fungal skin infection of young adults occurring most often during the summer. Pregnancy, warm climate, corticosteroids, and debilitation seem to be predisposing factors. Persons older than 40 years are rarely affected. The lesion consists of very fine, scaly patches that coalesce as they enlarge. The hypopigmented lesions are frequently seen on seborrheic areas of the body: the neck; the upper trunk; the upper arms; the shoulders; and, on occasion, the groin. The lesions are usually asymptomatic but may be mildly pruritic. Figure 5-78 shows the back of a patient with the classic hypopigmented patches of tinea versicolor. Figure 5-79 shows another patient with tinea versicolor.

Figure 5–78 Tinea versicolor.

Figure 5–79 Tinea versicolor.

A ganglion cyst, also known as a Bible cyst, is a chronic, painless lesion on the dorsum of the wrist or ankle. It results from leakage of synovial fluid through the tendon sheath of the capsule of the joint. This fluid eventually becomes encapsulated, and a cyst results. The term “Bible cyst” is derived from a common treatment in the past that consisted of hitting the cyst with a Bible or similarly large book. Striking the ganglion cyst with a large tome is usually sufficient to rupture the cyst, and reaccumulation is uncommon. Ganglion cysts are more common in women, and 70% occur in people between the ages of 20 and 40. Rarely, ganglion cysts can occur in children younger than 10 years. Multiple small cysts can give the appearance of more than one cyst, but a common stalk within the deeper tissue usually connects them. This type of cyst is not harmful and accounts for about half of all soft tissue tumors of the hand. Figure 5-80 shows a large ganglion cyst of the wrist, the typical location.

Figure 5–80 Ganglion cyst.

A spider angioma is a common pale red lesion, usually less than 2 cm in diameter, with a pulsating, central arteriole, often raised, surrounded by erythema and radiating “legs.” If pressure is exerted on the central body, blanching of the spider’s legs occurs. These benign lesions are commonly seen on the face, neck, arms, and upper trunk; they are rarely seen on the lower extremities. Although seen in normal individuals, spider angiomas are found more commonly in pregnant women and in patients with liver disease or vitamin B deficiency. These angiomas frequently become more evident during various times of a woman’s menstrual cycle. Figure 5-81 shows a spider angioma on the face of a young woman. Notice the central arteriole with the peripheral blush.

Figure 5–81 Spider angioma.

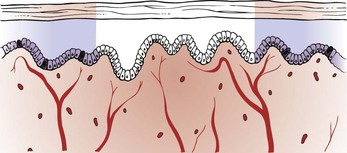

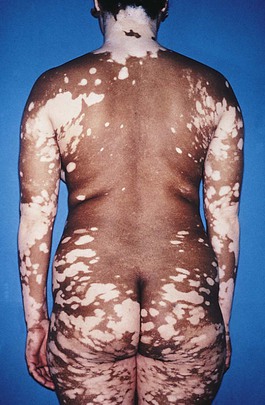

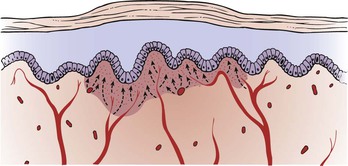

Vitiligo consists of patches of lightened skin resulting from decreased melanin pigmentation. Vitiligo is essentially a large macule that is totally depigmented. The epidermis manifests a complete absence of pigment, whereas the dermis is normal. Vitiligo can occur in any area, but it is commonly found on the neck, knees, elbows, and back of the hands. Figure 5-82 shows extensive vitiligo on the face and neck; a cross section is shown in Figure 5-83. Diffuse vitiligo is pictured in Figure 5-84.

Figure 5–82 Vitiligo.

Figure 5–83 Cross section through an area of vitiligo. Note the absence of melanocytes and skin pigment.

Figure 5–84 Diffuse vitiligo.

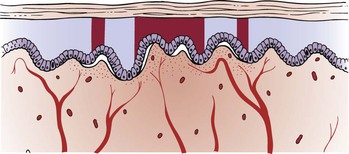

Urticaria is a common condition. The primary lesion is the wheal, or hive. In urticaria, the epidermis is normal. The dermis demonstrates papillary edema. Inflammatory cells may be found surrounding dilated blood vessels. Itching is a common complaint. There are several mechanisms for the development of urticaria, which include both immunologic and nonimmunologic causes. Regardless of the cause, the common factor is the release of substances, such as histamine, that change the vascular permeability and produce dermal edema. Figure 5-85 shows urticaria, and Figure 5-86 depicts the cross section.

Figure 5–85 Urticaria.

Figure 5–86 Cross section through an area of urticaria.

Erythema multiforme is an immunologic reaction in the skin triggered by various causative agents, including viruses, bacteria, drugs, and x-radiation. In many cases, the agent cannot be identified. As the name implies, the condition includes a variety of lesions: papules, bullae, plaques, and “target lesions.” Target lesions are the diagnostic lesions and have three zones of color: A central, tense bulla, or dark area, is surrounded by a zone of relative pallor that is rimmed by a thin area of erythema. Typically, target lesions are seen on the palms and soles (Fig. 5-87). The epidermis is usually normal. In the dermis, there is a subepidermal separation with inflammatory cells in the papillary dermis. Penicillin and sulfonamides are the drugs most commonly implicated as the cause of this condition. The most severe form of erythema multiforme involves the mucous membranes and is called Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The classic skin lesions of erythema multiforme are shown in Figures 5-88 and 5-89; Figure 5-90 illustrates a cross-sectional view.

Figure 5–88 Erythema multiforme.

Figure 5–89 Erythema multiforme.

Figure 5–90 Cross section through an area of erythema multiforme. Note the separation of the epidermis from the dermis.

Scabies is a common, intensely pruritic skin disorder caused by a mite, Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis. The female mite burrows into the stratum corneum of the skin and lays her eggs. A month or longer may pass before the symptom of generalized pruritus develops. The diagnostic physical sign is the burrow, which is a serpiginous, palpable track approximately 1 cm in length that may end in a papule, nodule, or tiny vesicle. The adult female mite is present in the burrow. The extremely pruritic rash of scabies has a predilection for the web spaces of the fingers and toes, as well as the groin. The buttocks are also frequently involved, as are the genitals of men and the nipples of women. A generalized papular or urticarial eruption may ensue after localized scabies infection. The presence of papules on the genitalia in a patient with intense pruritus should raise the strong suspicion of scabies. Outbreaks of scabies are common in population groups in which HIV infection is prevalent. Figure 5-91 shows the hand of a patient with scabies. Notice the classic eruption between the fingers. Figure 15-16 shows another patient with scabies; the papular rash in the groin and on the penis is clearly seen.

Figure 5–91 Scabies.

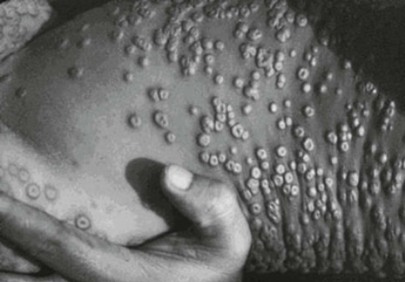

Norwegian scabies, also known as crusted scabies, is a rare, highly infectious form of scabies often seen in patients who are immunosuppressed, especially patients who are HIV positive, have lymphoma, who are cognitively impaired, or who are taking immunosuppressing medications. Unlike classical scabies, Norwegian scabies presents thick, exuding hyperkeratotic crusts with less or no itching. The dorsal aspects of the hands, the feet, and the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees are commonly involved. In Norwegian scabies, there appears to be a problem with the immune response to the mites, allowing for the infestation of an individual with hundreds of thousands to millions of the mites. The life cycle of the ectoparasite Sarcoptes is the same in classic scabies and Norwegian scabies, but the incubation period of the two vary largely. In a previously unexposed person, symptoms of classic scabies take 4 to 6 weeks to appear, but in Norwegian scabies they appear much faster, in 2 weeks at most. The number of mites present on the host body in the two cases differ significantly; compared with fewer than 20 mites in case of classical scabies, Norwegian scabies, as mentioned, is associated with millions of mites in extreme cases. Figure 5-92 shows the hand of a patient with Norwegian scabies. There have been many cases of Norwegian scabies in homeless AIDS patients reported, and this particular population is considered to be very susceptible for infection by the Sarcoptes mite. Neglected personal hygiene and impaired immune system both lead to the development of highly contagious Norwegian scabies infection, which keeps spreading to other individuals with a low immune state. Figure 5-93 shows the diffuse lesions of Norwegian scabies in a homeless AIDS patient.

Figure 5–92 Norwegian scabies.

Figure 5–93 Norwegian scabies.

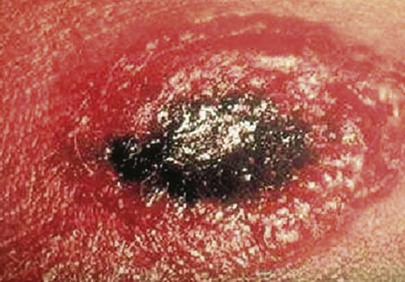

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon, cutaneous condition consisting of large, tender, necrotic ulcers having a violaceous, overhanging edge with a purulent base. Pyoderma gangrenosum occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 persons each year in the United States. Although pyoderma gangrenosum affects both sexes, a slight female predominance may exist. All ages may be affected by the disease, but it predominantly occurs in the fourth and fifth decades of life. The lesions are most frequently seen on the lower legs, but can also be seen on the dorsal surface of the hands, the extensor parts of the forearms, or on the face. It is associated with systemic diseases in at least 50% of patients who are affected. Although most often associated with inflammatory bowel disease, this condition is also seen in association with rheumatoid arthritis, various blood dyscrasias (especially multiple myeloma), chronic active hepatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and acute leukemias. Approximately 10% of all patients with ulcerative colitis, however, have cutaneous manifestations, especially pyoderma gangrenosum. The skin lesions of pyoderma gangrenosum are closely linked to the bowel disease; exacerbations of bowel symptoms are associated with extension of existing lesions or development of new ones. Removal of the diseased bowel often leads to improvement in the cutaneous manifestations. Figure 5-94 shows the classic shin lesions of pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with Crohn’s disease. See also Figure 14-6, which shows another patient with an exacerbation of ulcerative colitis and pyoderma gangrenosum of the shin.

Figure 5–94 Pyoderma gangrenosum of the shin.

Insect bites are common and should always be considered when a patient complains of a pruritic rash. Papules, vesicles, and wheals amid excoriations suggest the diagnosis. Papules in a grouped or linear arrangement on an arm or face suggest bedbug bites. These insects, which live in crevices in furniture, shun the light and feed at night on exposed areas of the body. They bite and then move around only to bite again. Figure 5-95 shows the linear papules on the arm of a patient who was bitten by bedbugs. Figure 5-96 shows another patient with persistent erythematous papules as a result of bedbug bites. Flea bites were the cause of the pruritic eruption on the feet of the patient shown in Figure 5-97. Notice the excoriations. The lower legs and feet are common sites for flea bites. Local reactions to bites from all kinds of toxic bugs look the same: redness, swelling, itching, and pain. Most spider bites are harmless, but occasionally, spider bites can cause severe allergic reactions. Bites by the venomous black widow and brown recluse spiders can be very dangerous to people. Figure 5-98 shows the face of a woman bitten under her left eye by a spider, possibly by a jumping spider. The patient pulled the spider off her face and suffered immediate pain, itching, and edema that lasted for more than 4 days. The jumping spider is probably the most common biting spider in the United States. People are caught by surprise and scared when they see the spider jump, especially if it jumps toward them. Bites from a jumping spider are painful and itchy, and cause redness and significant swelling. Other symptoms may include painful muscles and joints, headache, fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. The symptoms usually last approximately 1 to 4 days.

Figure 5–95 Bedbug bites.

Figure 5–96 Bedbug bites.

Figure 5–97 Flea bites.

Figure 5–98 Spider bite to lower eyelid.

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a neoplasm characterized by dark blue–purple macules, papules, nodules, and plaques. The classic form of the disease is a rare, slow-growing neoplasm occurring mostly on the lower extremities, especially the ankles and soles, of older men of Mediterranean or Jewish eastern European descent. The male-to-female ratio is 10 : 1 to 15 : 1, and the majority of patients are 60 to 80 years of age. Figure 5-99 shows a large reddish-colored plaque, which was slow-growing, on the sole of the foot of a 60-year-old man of eastern European origin. Some patients with classic KS may develop another type of cancer before the KS lesions appear or even later in life. Most often, this second cancer is non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Figure 5–99 Kaposi’s sarcoma: a classic plaque.

The most common type of KS in the United States today is epidemic or AIDS-related KS. This type of KS develops in people who are infected with HIV. A person infected with HIV does not necessarily have AIDS. The virus can be present in the body for a long time, typically many years, before causing major illness. The disease known as AIDS begins when the virus has seriously damaged the immune system, which results in certain types of infections and other medical complications, including KS. When HIV damages the immune system, people who also are infected with a certain virus (the KS herpesvirus) are more likely to develop KS. The risk of developing KS is closely linked to the CD4 count. The CD4 count is a measure of the effect of HIV on the immune system. The lower the CD4 count, the more likely that the patient will develop KS. KS is considered an “AIDS-defining” illness, meaning that when KS occurs in someone infected with HIV, that person officially has AIDS (and is not just HIV positive).

Approximately 35% of patients with AIDS who acquired the disease by sexual contact are affected, as opposed to approximately 5% of patients whose infection was acquired from intravenous drug use. Overall, 24% of all patients with AIDS develop this rapidly progressive form of the disease, also known as the epidemic AIDS-related form. The widely disseminated lesions are present on the legs, trunk, arms, neck, and head. They start as light-colored papules or nodules and coalesce into larger, darker lesions. Unlike the classic form, the epidemic AIDS-related form is commonly associated with visceral involvement, frequent oral lesions, and lymphadenopathy. This type of KS is different from other cancers in that lesions may begin in more than one place in the body at the same time. The average length of patient survival from the onset of the disease is 18 months. The skin lesions of epidemic AIDS-related KS are shown in Figure 5-100. Figure 5-100A shows the typical lesions on the arm and chest; Figure 5-100B shows the widely disseminated plaque lesions varying in color from dark red to violet; Figure 5-100C shows a violaceous lesion on the lateral aspect of the lower eyelid; Figure 5-100D shows a large confluent plaque of KS on the hard palate; Figure 5-100E shows a purplish-red, nodular lesion of KS on the gingiva and an infiltrative, violaceous lesion of the nose.

Figure 5–100 Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemic human immunodeficiency virus associated. A and B, Plaque lesions. C, Violaceous lesion affecting the lateral lower eyelid. D, Confluent plaque on the hard palate. E, Nodular lesion on the gingiva and the nose.

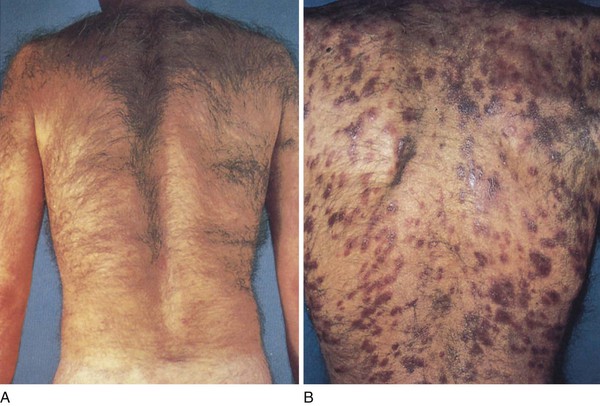

Figure 5-101 demonstrates the rapidity of the growth of epidemic AIDS-related KS. The initial manifestation (Fig. 5-101A) on the back of a 36-year-old man was only a few macular lesions of KS; a follow-up photograph, taken only 6 months later, shows the widely disseminated, purplish plaques of KS (Fig. 5-101B).

Figure 5–101 A, Early lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma on the back. B, Follow-up photograph, 6 months later, showing rapid development of purplish plaques of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

KS lesions are frequently seen on the feet. Figure 5-102 shows the foot of a patient who presented with this lesion between his fourth and fifth toes. A biopsy of the lesion confirmed the diagnosis of KS. This was the patient’s first manifestation of AIDS. Figure 5-103 shows the plantar arch of another patient who presented with painful nodules. A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of KS. KS of the heel is pictured in another patient in Figure 5-104.

Figure 5–102 Kaposi’s sarcoma between the toes.

Figure 5–103 Kaposi’s sarcoma on the plantar arch of the foot.

Figure 5–104 Kaposi’s sarcoma on the heel of the foot.

Scleroderma, also known as progressive systemic sclerosis, is an autoimmune, connective tissue disease that involves changes in the skin, blood vessels, muscles, and internal organs characterized by hardening of the skin. There is a broad spectrum of disease manifestations of scleroderma, ranging from limited skin lesions associated with calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal motility problems, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia (referred to as the CREST variant) to full encasement of the body by diffuse sclerosis. The cause of scleroderma is unknown. People with this condition have a buildup of collagen in the skin and other organs. This buildup leads to the symptoms of the disease. The disease usually affects people 30 to 50 years old. Women get scleroderma more often than men. Some people with scleroderma have a history of being around silica dust and polyvinyl chloride, but most do not. Vascular changes occur with visceral involvement and involve the microvessels and small arteries. The onset of the disease is often heralded by the development of Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is discussed in Chapter 12, The Peripheral Vascular System.

The cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma involve tightening of the skin, especially on the face and hands. As a result of tendon contractures, flexion of the fingers results. The fingers of a patient with scleroderma are shown in Figure 5-105; notice that the skin is bound tightly and obscures the superficial vasculature. Skin lines are absent. Figure 5-106 shows the face of the same patient. Notice the tightening and wrinkling of the skin around her mouth and the fixed, expressionless countenance as a result of flattening of the nasolabial folds. The patient had great difficulty in opening her mouth. The skin around the mouth has many furrows radiating outward, creating a mouselike appearance known as mauskopf.

Figure 5–105 Scleroderma: hands.

Figure 5–106 Scleroderma: face.

Calcification of the soft tissues can produce a stony-hard tissue and can range from a small area of involvement to massive calcium deposits. Figure 5-107A shows Raynaud’s phenomenon and calcinosis cutis in a patient with the CREST syndrome. Note the telangiectases of the fingertips. Figure 5-107B shows calcinosis cutis of the heel in the same patient. Commonly, the distal finger pad assumes a tapered appearance, with a tuft of scarred tissue between the fingertip and the nail bed. Ulceration can also occur, which can lead to osteomyelitis. Figure 5-108 shows the plantar view of the hallux in the same patient with CREST syndrome; note the characteristic tapering of the digit and pterygium inversus (growth of soft tissue along the ventral aspect of the nail plate).

Figure 5–107 Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal motility problems, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia (CREST) syndrome. A, Telangiectases of the fingertips. B, Calcinosis cutis of the heel.

Figure 5–108 Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal motility problems, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia (CREST) syndrome. With tapered digit and pterygium inversus.

The hallmark of erythema nodosum, an inflammatory disorder, is tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules that typically are located symmetrically on the shins. Erythema nodosum does not ulcerate and usually resolves without atrophy or scarring. Most direct and indirect evidence supports the involvement of a type IV delayed hypersensitivity response to numerous antigens. In approximately 55% of cases, the cause of erythema nodosum is unknown, but it has been associated with a wide variety of diseases, including infections. It is commonly associated with streptococcal infections, in approximately 28% to 48% of all cases, and has been associated with chlamydia, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, mycobacteria, and mycoplasma. In addition to the association with infections, erythema nodosum is associated with sarcoidosis (11–25% of all cases); inflammatory bowel disease (1–4% of all cases); pregnancy (2–5% of all cases); medications (3–10% of all cases) such as sulfonamides, oral contraceptives, and bromides; vaccinations; and cancer. Erythema nodosum may also occur on the buttocks, calves, ankles, thighs, and arms. The lesions begin as flat, firm, hot, red, painful lumps approximately an inch across. Within a few days they may become purplish, then over several weeks fade to a brownish, flat patch. Patients, primarily young women, seek medical attention after the appearance of these extremely painful lesions, which range in size from 1 cm to several centimeters in diameter. The lesions can then coalesce and spread over the entire leg. The lesions of erythema nodosum begin to regress after 1 to 2 weeks. As they disappear, they undergo a series of characteristic color changes: bright erythema to shades of purple, yellow, and green. Figure 5-109 shows the early lesions of erythema nodosum in a 33-year-old woman in whom sarcoidosis was diagnosed 3 months later.

Figure 5–109 Erythema nodosum.