Chapter 3 The Skin

Basic Terminology and Diagnostic Techniques

1 How many skin diseases exist? What are the two main categories of skin lesions?

There are more than 1400 skin diseases. Yet, only 30 are important, common, and worth knowing. The first step toward their recognition is the separation of primary from secondary lesions (Table 3-1).

Primary lesions result only from disease and have not been changed by additional events (such as trauma, scratching, or medical treatment; see Table 3-1). To better identify primary lesions, pay attention to their colors, shape, arrangement, and distribution.

Primary lesions result only from disease and have not been changed by additional events (such as trauma, scratching, or medical treatment; see Table 3-1). To better identify primary lesions, pay attention to their colors, shape, arrangement, and distribution.

Secondary lesions instead have been altered by outside manipulation, medical treatment, or their own natural course.

Secondary lesions instead have been altered by outside manipulation, medical treatment, or their own natural course.

| skin lesions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Special |

| Solid (Nonpalpable) | Crusts | Purpurae |

| • Macules (≤0.5 cm) | Scales | Petechiae |

| • Patches (>0.5 cm) | Ulcers | Ecchymoses |

| Fissures | Teleangiectasias | |

| Solid (Palpable) | Excorations | Comedones |

| • Papules (≤0.5 cm) | Scars | Burrows |

| • Plaques (>0.5 cm) | Erosions | Target lesions |

| • Nodules (deeper plaques) | Lichenification | |

| • Wheals (pruritic plaques) | Atrophy | |

| • Tumors (larger nodules) | Scars | |

| Sinuses | ||

| Fluid-Lesions | ||

| • Vesicles (fluid-filled papules) | ||

| • Pustules (pus-filled papules) | ||

| • Bullae (fluid-filled plaques) | ||

| • Cysts (fluid-filled nodules) | ||

2 What are the major primary lesions?

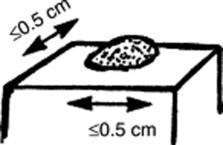

Macules: Flat, nonpalpable, circumscribed areas of discoloration ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical macules are the familiar freckles.

Macules: Flat, nonpalpable, circumscribed areas of discoloration ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical macules are the familiar freckles.

Patches: Flat, nonpalpable areas of skin discoloration >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large macule). A typical patch is the one of vitiligo.

Patches: Flat, nonpalpable areas of skin discoloration >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large macule). A typical patch is the one of vitiligo.

Papules: Raised and palpable lesions ≤0.5 cm in diameter. They may or may not have a different color from the surrounding skin. A typical papule is a raised nevus.

Papules: Raised and palpable lesions ≤0.5 cm in diameter. They may or may not have a different color from the surrounding skin. A typical papule is a raised nevus.

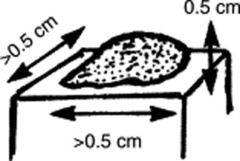

Plaques: Raised and palpable lesions >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large papule). Usually confined to the superficial dermis, they may result from the confluence of papules. A typical plaque is that of psoriasis.

Plaques: Raised and palpable lesions >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large papule). Usually confined to the superficial dermis, they may result from the confluence of papules. A typical plaque is that of psoriasis.

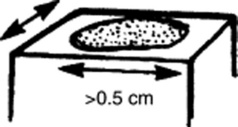

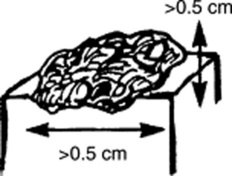

Nodules: Raised, palpable, and elevated lesions >0.5 cm in diameter, which, unlike plaques, go deeper into the dermis. Since they are below the surface of the skin, the overlying cutis is usually mobile. Typical nodules are those of erythema nodosum.

Nodules: Raised, palpable, and elevated lesions >0.5 cm in diameter, which, unlike plaques, go deeper into the dermis. Since they are below the surface of the skin, the overlying cutis is usually mobile. Typical nodules are those of erythema nodosum.

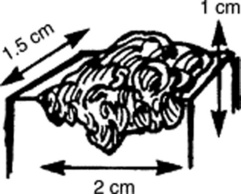

Tumors: Nodules that are either >2 cm in diameter or poorly demarcated. Usually neoplastic.

Tumors: Nodules that are either >2 cm in diameter or poorly demarcated. Usually neoplastic.

Wheals (hives): Raised, circumscribed, edematous, and typically pruritic plaques that are pink or pale but typically transient. Classic wheals are the lesions of urticaria, or of a mosquito bite.

Wheals (hives): Raised, circumscribed, edematous, and typically pruritic plaques that are pink or pale but typically transient. Classic wheals are the lesions of urticaria, or of a mosquito bite.

Vesicles (blisters): Fluid-filled, circumscribed, and raised lesions that contain clear serous fluid and are ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical vesicles are those of herpes simplex.

Vesicles (blisters): Fluid-filled, circumscribed, and raised lesions that contain clear serous fluid and are ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical vesicles are those of herpes simplex.

Bullae: Vesicles >0.5 cm in diameter. Commonly seen in patients with second-degree burns. Presence of a bulla is so important that it usually trumps all other concomitant primary lesions.

Bullae: Vesicles >0.5 cm in diameter. Commonly seen in patients with second-degree burns. Presence of a bulla is so important that it usually trumps all other concomitant primary lesions.

Cysts: Raised and encapsulated lesions that contain fluid or semi-solid material. Typical are the cysts of acne.

Cysts: Raised and encapsulated lesions that contain fluid or semi-solid material. Typical are the cysts of acne.

Pustules: Pus-filled papules. Typically seen in patients with impetigo or acne.

Pustules: Pus-filled papules. Typically seen in patients with impetigo or acne.

Purpura: Skin extravasation of red cells, which, based on size, may present as petechiae or ecchymoses. Palpable purpura is never normal and argues for an antigen-antibody complex (vasculitis). Often localized to the lower extremities, the lesions of Henoch-Schönlein are typical examples of a palpable purpura. Internal organs (kidneys, GI tract) are often involved too.

Purpura: Skin extravasation of red cells, which, based on size, may present as petechiae or ecchymoses. Palpable purpura is never normal and argues for an antigen-antibody complex (vasculitis). Often localized to the lower extremities, the lesions of Henoch-Schönlein are typical examples of a palpable purpura. Internal organs (kidneys, GI tract) are often involved too.

Petechiae: Reddish-to-purple discolorations, caused by a microscopic hemorrhage. These are <0.5 cm in diameter and usually in clusters. With the exception of color, they resemble papules or macules (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typical petechiae are those of typhus. The lesions of thrombocytopenic thrombotic purpura (TTP) are typical petechiae too.

Petechiae: Reddish-to-purple discolorations, caused by a microscopic hemorrhage. These are <0.5 cm in diameter and usually in clusters. With the exception of color, they resemble papules or macules (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typical petechiae are those of typhus. The lesions of thrombocytopenic thrombotic purpura (TTP) are typical petechiae too.

Ecchymoses (bruises): Reddish-to-purple discolorations larger than petechiae. Except for color, they resemble plaques and patches (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typically located below an intact epithelial surface.

Ecchymoses (bruises): Reddish-to-purple discolorations larger than petechiae. Except for color, they resemble plaques and patches (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typically located below an intact epithelial surface.

Spider angiomas: These are arterial teleangiectasias, i.e., vascular arterial lesions that resemble the legs of a spider. They fill from the center and blanch whenever this is compressed.

Spider angiomas: These are arterial teleangiectasias, i.e., vascular arterial lesions that resemble the legs of a spider. They fill from the center and blanch whenever this is compressed.

Venous spiders: These are venousteleangiectasias, i.e., vascular venous lesions that also resemble the legs of a spider. Hence, they fill from the periphery, not the center. They empty with pressure.

Venous spiders: These are venousteleangiectasias, i.e., vascular venous lesions that also resemble the legs of a spider. Hence, they fill from the periphery, not the center. They empty with pressure.

3 What are the major secondary lesions?

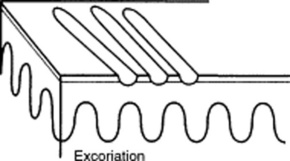

Excoriations: Linear erosions produced by scratching. Often raised, scratch marks may also present as crust on top of a primary lesion that has been partially scratched off. They are almost exclusively confined to the eczematous diseases.

Excoriations: Linear erosions produced by scratching. Often raised, scratch marks may also present as crust on top of a primary lesion that has been partially scratched off. They are almost exclusively confined to the eczematous diseases.

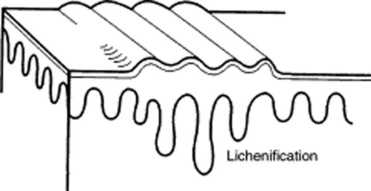

Lichenification: A typical skin thickening seen in chronic pruritus with recurrent scratching. Resembles the callus formation of palms and soles after recurrent trauma. Lichenified skin is hardened, leather-like, with prominent markings and some scaling. Like excoriation, lichenification is typical of eczematous diseases. In fact, it is considered pathognomonic of atopic dermatitis.

Lichenification: A typical skin thickening seen in chronic pruritus with recurrent scratching. Resembles the callus formation of palms and soles after recurrent trauma. Lichenified skin is hardened, leather-like, with prominent markings and some scaling. Like excoriation, lichenification is typical of eczematous diseases. In fact, it is considered pathognomonic of atopic dermatitis.

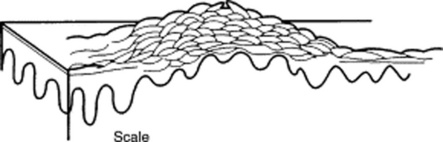

Scales: Raised lesions presenting as flaking of the upper skin surface. In fact, they represent thickening of the stratum corneum, the uppermost layer of the epidermis. Scales may be white, gray, or tan. They may also be small or rather large. They provide the squamous component to papulosquamous diseases. They are extremely common in the scalp, where they suggest either banal processes (dandruff) or more serious conditions (seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea capitis).

Scales: Raised lesions presenting as flaking of the upper skin surface. In fact, they represent thickening of the stratum corneum, the uppermost layer of the epidermis. Scales may be white, gray, or tan. They may also be small or rather large. They provide the squamous component to papulosquamous diseases. They are extremely common in the scalp, where they suggest either banal processes (dandruff) or more serious conditions (seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea capitis).

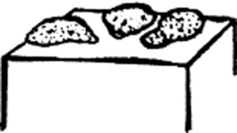

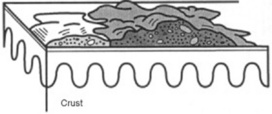

Crusts: Raised lesions produced by dried serum and blood cell remnants. Usually preceded by fluid-filled primary lesions (i.e., vesicles, pustules, or bullae). The most familiar crust is the “scab” of impetigo.

Crusts: Raised lesions produced by dried serum and blood cell remnants. Usually preceded by fluid-filled primary lesions (i.e., vesicles, pustules, or bullae). The most familiar crust is the “scab” of impetigo.

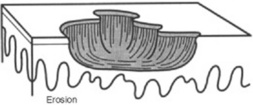

Erosions: Depressed lesions produced whenever the epidermis is either removed or sloughed. They are moist, usually red, and well circumscribed. Classic erosions are those of chickenpox following rupture of a vesicle.

Erosions: Depressed lesions produced whenever the epidermis is either removed or sloughed. They are moist, usually red, and well circumscribed. Classic erosions are those of chickenpox following rupture of a vesicle.

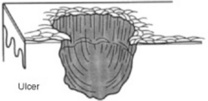

Ulcers: Depressed lesions produced whenever not only the epidermis but also part (or all) of the dermis is gone. Ulcers are concave, often moist, and at times inflamed or even hemorrhagic. They heal with scarring. A classic ulcer is that of the syphilitic chancre.

Ulcers: Depressed lesions produced whenever not only the epidermis but also part (or all) of the dermis is gone. Ulcers are concave, often moist, and at times inflamed or even hemorrhagic. They heal with scarring. A classic ulcer is that of the syphilitic chancre.

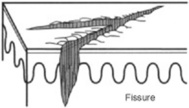

Fissures: Depressed lesions presenting as narrow, linear, and vertical cracks that penetrate through the epidermis, reaching at least part of the dermis. Classic fissures are those of the athlete’s foot.

Fissures: Depressed lesions presenting as narrow, linear, and vertical cracks that penetrate through the epidermis, reaching at least part of the dermis. Classic fissures are those of the athlete’s foot.

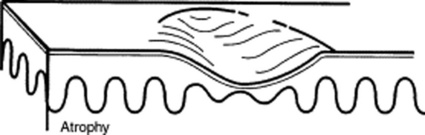

Atrophy: Usually the nonspecific end-product of various skin disorders. It is characterized by a pale and shiny area, with loss of cutaneous markings and full skin thickness.

Atrophy: Usually the nonspecific end-product of various skin disorders. It is characterized by a pale and shiny area, with loss of cutaneous markings and full skin thickness.

Sinuses: Connective channels between the surface of the skin and deeper components.

Sinuses: Connective channels between the surface of the skin and deeper components.

4 Are there other ways to classify skin lesions?

Many ways. One divides lesions into four groups based on the relationship with the surrounding skin:

6 What is the configuration of a skin lesion?

It is the outline of the lesion as observed from above. The most common configurations are:

Annular: Doughnut-shaped lesions. Fungal infections present as red rings with the scaly surface.

Annular: Doughnut-shaped lesions. Fungal infections present as red rings with the scaly surface.

Linear: Lesions arranged in a line. For example, streaks of small vesicles on an erythematous base. The most common linear lesion is the rash of poison ivy, also called rhus dermatitis (rhus is the Greek word for sumac, which describes various shrubs or small trees). Some species of sumac, or rhus, include poison ivy and poison oak—both cause an acute itching rash on contact.

Linear: Lesions arranged in a line. For example, streaks of small vesicles on an erythematous base. The most common linear lesion is the rash of poison ivy, also called rhus dermatitis (rhus is the Greek word for sumac, which describes various shrubs or small trees). Some species of sumac, or rhus, include poison ivy and poison oak—both cause an acute itching rash on contact.

Reticular: Lesions organized in a net-like cluster

Reticular: Lesions organized in a net-like cluster

Gyrate: Lesions with a serpiginous (or polycyclic) configuration—as in gyrate erythema

Gyrate: Lesions with a serpiginous (or polycyclic) configuration—as in gyrate erythema

9 And so, what are the required components of a dermatologic diagnosis?

Morphology: Color, shape, dimensions (width and height, if necessary), elevation/depression, and palpable features (smoothness, induration, tenderness, scaling, and crusting)

Morphology: Color, shape, dimensions (width and height, if necessary), elevation/depression, and palpable features (smoothness, induration, tenderness, scaling, and crusting)

Distribution (body location): Generalized versus localized

Distribution (body location): Generalized versus localized

Distribution (arrangement to one another): Clustered, confluent, dermatomal

Distribution (arrangement to one another): Clustered, confluent, dermatomal

10 What are the tools necessary for a dermatologic diagnosis?

Wood’s lamp: A fluorescent and long-wave ultraviolet light that has been narrowed to 360 nm. Developed by Robert Wood (1868–1955), it is commonly relied on for detecting fungal lesions, areas of hypopigmentation, and porphyrin compounds. In a darkened room, it reveals fungal infections (like tinea capitis) as sharply marginated patches of bright blue-green. Since melanin absorption is at 360 nm, it also identifies areas of vitiligo or tinea versicolor (hypopigmented patches as pale-white, and depigmented areas as bright-white). Finally, it makes porphyrin compounds stand out as coral red fluorescence, like in erythrasma, a bacterial infection of intertriginous areas (axillae).

Wood’s lamp: A fluorescent and long-wave ultraviolet light that has been narrowed to 360 nm. Developed by Robert Wood (1868–1955), it is commonly relied on for detecting fungal lesions, areas of hypopigmentation, and porphyrin compounds. In a darkened room, it reveals fungal infections (like tinea capitis) as sharply marginated patches of bright blue-green. Since melanin absorption is at 360 nm, it also identifies areas of vitiligo or tinea versicolor (hypopigmented patches as pale-white, and depigmented areas as bright-white). Finally, it makes porphyrin compounds stand out as coral red fluorescence, like in erythrasma, a bacterial infection of intertriginous areas (axillae).

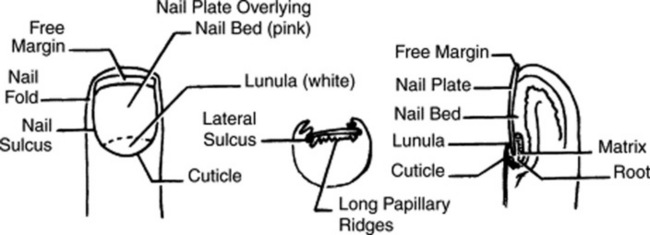

14 How should fingernails and toenails be assessed?

If covered by polish, clean them first with a solvent like acetone. Then pay attention to color and shape but also to anatomic details (Fig. 3-25):

15 What systemic conditions are associated with changes in nail shape or growth?

Clubbing: Inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary malignancy, asbestosis, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, congenital heart disease, endocarditis, atrioventricular malformation and fistulas (see also question 19)

Clubbing: Inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary malignancy, asbestosis, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, congenital heart disease, endocarditis, atrioventricular malformation and fistulas (see also question 19)

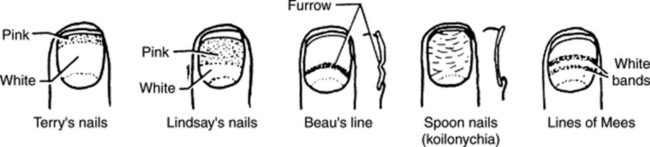

Koilonychia (spoon nails) (Fig. 3-26): Iron deficiency anemia, hemochromatosis, Raynaud’s disease, systemic lupus disease, trauma, nail-patella syndrome

Koilonychia (spoon nails) (Fig. 3-26): Iron deficiency anemia, hemochromatosis, Raynaud’s disease, systemic lupus disease, trauma, nail-patella syndrome

Onycholysis: Psoriasis, infection, hyperthyroidism, sarcoidosis, trauma, amyloidosis, connective tissue disorders

Onycholysis: Psoriasis, infection, hyperthyroidism, sarcoidosis, trauma, amyloidosis, connective tissue disorders

Pitting: Psoriasis, Reiter’s syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti, alopecia areata

Pitting: Psoriasis, Reiter’s syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti, alopecia areata

Beau’s lines (see Fig. 3-26): Any severe systemic illness that disrupts nail growth, Raynaud’s disease, pemphigus, trauma

Beau’s lines (see Fig. 3-26): Any severe systemic illness that disrupts nail growth, Raynaud’s disease, pemphigus, trauma

Yellow nail: Lymphedema, pleural effusion, immunodeficiency, bronchiectasis, sinusitis, rheumatoid arthritis, nephrotic syndrome, thyroiditis, tuberculosis, Raynaud’s disease

Yellow nail: Lymphedema, pleural effusion, immunodeficiency, bronchiectasis, sinusitis, rheumatoid arthritis, nephrotic syndrome, thyroiditis, tuberculosis, Raynaud’s disease

16 What systemic conditions are associated with changes in nail color?

Terry’s nails (see Fig. 3-26): Hepatic failure, cirrhosis, diabetes, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, malnutrition

Terry’s nails (see Fig. 3-26): Hepatic failure, cirrhosis, diabetes, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, malnutrition

Azure lunula: Wilson’s disease, silver poisoning, quinacrine

Azure lunula: Wilson’s disease, silver poisoning, quinacrine

Lindsay’s nails (half-and-half nails) (see Fig. 3-26): Specific for renal failure

Lindsay’s nails (half-and-half nails) (see Fig. 3-26): Specific for renal failure

Muehrcke’s lines: Specific for hypoalbuminemia

Muehrcke’s lines: Specific for hypoalbuminemia

Lines of Mees’ (see Fig. 3-26): Arsenic poisoning, Hodgkin’s disease, congestive heart failure, leprosy, malaria, chemotherapy, carbon monoxide poisoning, other systemic insults

Lines of Mees’ (see Fig. 3-26): Arsenic poisoning, Hodgkin’s disease, congestive heart failure, leprosy, malaria, chemotherapy, carbon monoxide poisoning, other systemic insults

Dark longitudinal streaks: Melanoma, benign nevus, chemical staining, normal variant in darkly pigmented people

Dark longitudinal streaks: Melanoma, benign nevus, chemical staining, normal variant in darkly pigmented people

Longitudinal striations: Alopecia areata, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis

Longitudinal striations: Alopecia areata, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis

Splinter hemorrhage: Subacute bacterial endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, malignancies, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, psoriasis, trauma

Splinter hemorrhage: Subacute bacterial endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, malignancies, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, psoriasis, trauma

Telangiectasia: Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma

Telangiectasia: Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma

Nails

19 What is clubbing?

A condition that can be (1) idiopathic; (2) congenital (dominant trait); or (3) a clue to serious underlying pathology, including cardiovascular, hepatobiliary, mediastinal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, neoplastic, infectious, and, especially, pulmonary (see Chapter 13, questions 101–116).

22 What are the nail findings of psoriasis?

Pitting (previously discussed)

Pitting (previously discussed)

Oil spot or salmon patch/nail bed: The most diagnostic nail sign; it consists of a translucent, yellow-red discolored patch in the nail bed, resembling a drop of oil beneath the plate.

Oil spot or salmon patch/nail bed: The most diagnostic nail sign; it consists of a translucent, yellow-red discolored patch in the nail bed, resembling a drop of oil beneath the plate.

Beau’s lines in the proximal nail matrix (see later)

Beau’s lines in the proximal nail matrix (see later)

Leukonychia: Areas of white nail plate; due to parakeratotic foci in the mid-matrix

Leukonychia: Areas of white nail plate; due to parakeratotic foci in the mid-matrix

Subungual hyperkeratosis: Excessive proliferation of the nail bed that can lead to onycholysis

Subungual hyperkeratosis: Excessive proliferation of the nail bed that can lead to onycholysis

Nail plate crumbling: Weakened nail plate, bed, and matrix from diseased underlying structures

Nail plate crumbling: Weakened nail plate, bed, and matrix from diseased underlying structures

Splinter hemorrhages: Longitudinal black lines due to tiny capillary hemorrhages between the nail bed and plate; analogous to Auspitz sign (pinpoint bleeding under the psoriatic plaque)

Splinter hemorrhages: Longitudinal black lines due to tiny capillary hemorrhages between the nail bed and plate; analogous to Auspitz sign (pinpoint bleeding under the psoriatic plaque)

Dilated tortuous capillaries in the dermal papillae

Dilated tortuous capillaries in the dermal papillae

Spotted lunula: Distal matrix involvement characterized by erythema of the lunula

Spotted lunula: Distal matrix involvement characterized by erythema of the lunula

26 What is longitudinal ridging (Reedy nails)?

A normal variant of patients older than 50, but one that also can occur in younger subjects. It may even represent a brittle nail variation. Ridges typically extend from the proximal nail fold to the distal plate, with some being very prominent, especially in older women. They are usually multiple, but at times may be single—like in patients with lichen planus (see questions 38 and 210–216).

38 What is lichen planus of the nail?

A condition present in 10% of patients with lichen planus. The most common finding is thinning of the nail plate, leading to longitudinal grooving and ridging (see also question 26). Hyperpigmentation, subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and longitudinal melanonychia can also be present.

41 What are azure half-moons in nail beds?

The nails of Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration). Lunulae are not white, but bluish.

48 What is paronychia?

An acute or chronic inflammation of the perionychium, with redness, swelling, and tenderness.

Fluid-Filled Lesions: PUS (Pustules)—Table 3-2

Acne

54 What does acne look like?

| Fluid-Filled Lesions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pus-Filled | Clear Fluid | |

| Pustular | Vesiculo-Bullous | Bullous |

| Acne vulgaris | H. simplex | Pemphygus vulgaris |

| Acne rosacea | H. zoster/varicella | Pemphygoid |

| Steroid acne | Dermatophytoses | Drug reactions |

| • Erythema multiforme | ||

| • Stevens-Johnson | ||

| • TEN | ||

| Folliculitis (bacterial/fungal) | Insect bites | Poison ivy/contact dermatitis |

| Intertriginous candidiasis | Dermatitis herpetiformis | Bullous impetigo |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | ||

| Lupus erythematosus | ||

Fluid-Filled Lesions: Clear Fluid (Vesiculobullous Diseases)

62 What is the typical clinical course of herpes simplex?

Primary (initial) outbreaks: Usually more severe, with pain, edema, and a prolonged course. Still, the majority of primary infections go unnoticed because symptoms are either absent or so minimal that only the recurrent episodes are recognized.

Primary (initial) outbreaks: Usually more severe, with pain, edema, and a prolonged course. Still, the majority of primary infections go unnoticed because symptoms are either absent or so minimal that only the recurrent episodes are recognized.

Secondary (recurrent) disease: Less severe and shorter in duration. In fact, the hallmark of mucocutaneous herpes simplex is its ability to remain dormant in ganglia, eventually recurring in areas of primary infection. Frequency of recurrences varies, but for genital and labial herpes, the average is four episodes per year. Approximately 50% of patients with genital herpes have one or more episodes, often from local trauma, menses, and even stress.

Secondary (recurrent) disease: Less severe and shorter in duration. In fact, the hallmark of mucocutaneous herpes simplex is its ability to remain dormant in ganglia, eventually recurring in areas of primary infection. Frequency of recurrences varies, but for genital and labial herpes, the average is four episodes per year. Approximately 50% of patients with genital herpes have one or more episodes, often from local trauma, menses, and even stress.

63 What are the other clinical presentations of herpes simplex?

Herpetic gingivostomatitis: Presents in children and young adults with fever, malaise, sore throat, painful vesicles, and erosions of tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips

Herpetic gingivostomatitis: Presents in children and young adults with fever, malaise, sore throat, painful vesicles, and erosions of tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips

Herpetic whitlow (middle English for white flaw; also referred to as a felon): This is an occupational hazard of medical and dental professionals caused by exposure to the virus in a patient’s mouth. It is characterized by vesicles and edema of a digit, sometimes associated with erythema, lymphangitis, and lymphadenopathy of the arm. It may last for several weeks.

Herpetic whitlow (middle English for white flaw; also referred to as a felon): This is an occupational hazard of medical and dental professionals caused by exposure to the virus in a patient’s mouth. It is characterized by vesicles and edema of a digit, sometimes associated with erythema, lymphangitis, and lymphadenopathy of the arm. It may last for several weeks.

Herpes simplex in immunosuppressed patients: Frequently produces more severe and persistent ulceration, as well as disseminated cutaneous and systemic lesions

Herpes simplex in immunosuppressed patients: Frequently produces more severe and persistent ulceration, as well as disseminated cutaneous and systemic lesions

66 Who develops varicella?

Mostly children younger than 10 years. Only 5% of cases occur in subjects older than 15.

73 What are the other presentations of herpes zoster?

Involvement of the eye (ophthalmic branch): Heraldic lesions appear on the tip of the nose, due to infection of the nasociliary nerve. Get immediate ophthalmologic consultation.

Involvement of the eye (ophthalmic branch): Heraldic lesions appear on the tip of the nose, due to infection of the nasociliary nerve. Get immediate ophthalmologic consultation.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome: Due to involvement of the geniculate ganglion with facial paralysis. Lesions occur over the external auditory canal or tympanic membrane, with or without vertigo, tinnitus, deafness/hyperacusis, unilateral loss of taste, and decrease in tear formation and salivation. Described by the Philadelphia neurologist James Ramsay Hunt (1874–1937).

Ramsay Hunt syndrome: Due to involvement of the geniculate ganglion with facial paralysis. Lesions occur over the external auditory canal or tympanic membrane, with or without vertigo, tinnitus, deafness/hyperacusis, unilateral loss of taste, and decrease in tear formation and salivation. Described by the Philadelphia neurologist James Ramsay Hunt (1874–1937).

Zoster in immunocompromised patients: Seen in patients with AIDS and malignancies (especially lymphocytic leukemia or Hodgkin’s) and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Usually more severe and often disseminated. Chronic eruptions can be the first sign of HIV infection.

Zoster in immunocompromised patients: Seen in patients with AIDS and malignancies (especially lymphocytic leukemia or Hodgkin’s) and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Usually more severe and often disseminated. Chronic eruptions can be the first sign of HIV infection.

79 Are there any other causes of PV?

A form of PV (but also BP, see question 80) can be drug induced, resulting from penicillamine, captopril, thiol-containing compounds, and rifampin. Emotional stress can also trigger it. Finally, PV may occur in other autoimmune diseases, including myasthenia gravis and thymoma.

82 What is Asboe-Hansen sign?

Another sign of PV; lateral pressure on the edge of a blister may spread it into unaffected skin.

84 What is erythema multiforme (EM)?

A relatively benign process characterized by target or targetoid lesions, with or without blisters, in a symmetric and acral distribution. In fact, the rash favors palms and soles, dorsum of hands, face, and extensor surfaces of extremities (Fig. 3-27). It is often associated with oral lesions, but rarely involves more than one mucosal surface. Although it can be caused by drugs, it is most commonly a sequela of herpes virus infection. It has low morbidity, no mortality, but frequent recurrences. It may be associated with epidermal detachment, yet denudation always involves <10% of BSA.

85 What is Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)?

A potential dermatologic emergency. First described in 1922 by the American pediatricians Albert Stevens and Frank Johnson, SJS is characterized by widespread purpuric macules and targetoid lesions, usually more common on face and torso, and with concomitant mucosal involvement of more than one site (usually the eyes, mouth, and genitalia; Fig. 3-28). Lesions may undergo full-thickness epidermal necrosis, although this is limited by definition to <10% of cutaneous surface. Hence, mortality is much less than in TEN (only 5%).

86 What is toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)?

Also known as Lyell’s syndrome, this is a true dermatologic emergency characterized by widespread skin and mucosal denudation. Skin lesions are erythematous and target-like macules associated with full-thickness epidermal necrosis and detachment of >30% BSA (Fig. 3-29). It is fatal in 50% of the cases, usually because of sepsis and respiratory distress. Mortality is related to BSA involvement: 11% for BSA (which is actually more of a SJS-TEN transitional form), and 35% for BSA >30%.

91 What are the sequelae of SJS/TEN?

97 What are the most common photosensitizing medications?

101 What is the clinical course of urticaria?

Acute urticaria resolves in 4–6 weeks. It is usually associated with drugs (penicillin, sulfonamides, aspirin); food allergens (e.g., chocolate, shellfish, eggs, cheese, nuts, peanut butter, berries, tomatoes, strawberries); new pets; or infections (upper respiratory infection, especially streptococcal in children). Pregnancy may aggravate it into pruritic and urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP syndrome).

Acute urticaria resolves in 4–6 weeks. It is usually associated with drugs (penicillin, sulfonamides, aspirin); food allergens (e.g., chocolate, shellfish, eggs, cheese, nuts, peanut butter, berries, tomatoes, strawberries); new pets; or infections (upper respiratory infection, especially streptococcal in children). Pregnancy may aggravate it into pruritic and urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP syndrome).

Chronic urticaria is instead longer than 6 weeks and may last for years. One half of patients are free of symptoms at 12 months, but 20% have lesions that persist for decades. In 80% of cases, the etiology remains unknown, with possibilities including the same causes of acute urticaria, as well as cryoglobulins, autoimmune diseases, food additives, inhalants, viruses (hepatitis B), parasites, arthropods (scabies and fleas), neoplasms, and even stress (often responding to hypnosis). Still, physical factors are the most commonly identifiable etiologies of chronic urticaria, being responsible for one out of five cases. Among them are cold, water, sun, pressure, vibration, and even stroking (demographism), often coexisting in the individual patient. Physical urticarias are easily recognized by challenge testing.

Chronic urticaria is instead longer than 6 weeks and may last for years. One half of patients are free of symptoms at 12 months, but 20% have lesions that persist for decades. In 80% of cases, the etiology remains unknown, with possibilities including the same causes of acute urticaria, as well as cryoglobulins, autoimmune diseases, food additives, inhalants, viruses (hepatitis B), parasites, arthropods (scabies and fleas), neoplasms, and even stress (often responding to hypnosis). Still, physical factors are the most commonly identifiable etiologies of chronic urticaria, being responsible for one out of five cases. Among them are cold, water, sun, pressure, vibration, and even stroking (demographism), often coexisting in the individual patient. Physical urticarias are easily recognized by challenge testing.

102 What are the other clinical presentations of urticaria?

1. Hereditary angioedema: Autosomal dominant, it presents in the second to fourth decade of life with sudden attacks of angioedema that often last for days and can be life threatening. Due to low or nonfunctional C1 inhibitor, with diagnosis being suggested by a low C4 level.

2. Physical urticarias: appear in response to a stimulus, such as cold, sunlight, trauma, water:

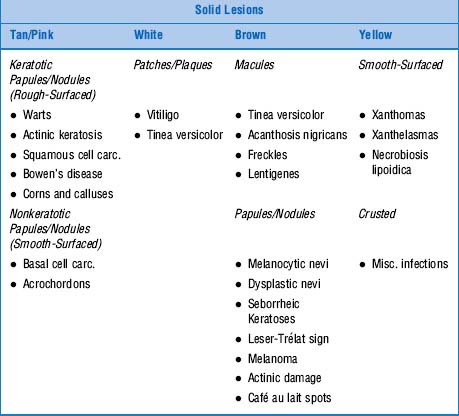

Solid Lesions: Tan Or Pink—Table 3-3

106 How are warts transmitted?

By direct or indirect contact, especially when the normal epithelial barrier has been disrupted.

107 What are the major types of warts?

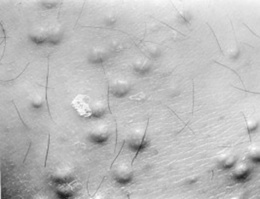

Common wart: Often referred to as verruca vulgaris, it presents as a rough-surfaced, scaly, and circumscribed papule, <1 mm to >0.5 cm in size. Most commonly located on hands and knees, although it can occur anywhere (Fig. 3-30). Often accompanied by “black seeds” (i.e., thrombosed capillaries). Usually asymptomatic, warts may cause cosmetic disfigurement or tenderness.

Common wart: Often referred to as verruca vulgaris, it presents as a rough-surfaced, scaly, and circumscribed papule, <1 mm to >0.5 cm in size. Most commonly located on hands and knees, although it can occur anywhere (Fig. 3-30). Often accompanied by “black seeds” (i.e., thrombosed capillaries). Usually asymptomatic, warts may cause cosmetic disfigurement or tenderness.

Filiform wart: Long and slender growth, usually around lips, eyelids, or nares

Filiform wart: Long and slender growth, usually around lips, eyelids, or nares

Condyloma: A genital wart, mostly of the anus, vulva, or glans. Presents as a flat-topped papule with an irregular surface. Condylomata may be pink at first, but turn tan or brown with time.

Condyloma: A genital wart, mostly of the anus, vulva, or glans. Presents as a flat-topped papule with an irregular surface. Condylomata may be pink at first, but turn tan or brown with time.

(Palmo)plantar wart: Involving the soles or dorsi of feet, but also toes. Often callused, it presents as a white, irregularly surfaced area—with or without black dots. Plantar warts are usually painful, and when extensively involving the soles, they may impair ambulation. Deep palmoplantar warts are also termed myrmecia (from the Greek murmekos, ants). They begin as small shiny papules that progress into deep and sharply defined rounded lesions, with a rough keratotic surface and a smooth collar of thickened horn. Since they grow deep, they are more painful than common warts.

(Palmo)plantar wart: Involving the soles or dorsi of feet, but also toes. Often callused, it presents as a white, irregularly surfaced area—with or without black dots. Plantar warts are usually painful, and when extensively involving the soles, they may impair ambulation. Deep palmoplantar warts are also termed myrmecia (from the Greek murmekos, ants). They begin as small shiny papules that progress into deep and sharply defined rounded lesions, with a rough keratotic surface and a smooth collar of thickened horn. Since they grow deep, they are more painful than common warts.

Flat wart: Also called “plane warts” (or verruca plana). Flat and flesh-colored papules, >1–5 mm in size. Smooth or slightly hyperkeratotic, they may number just a few or in the hundreds, at times becoming grouped or confluent, and often acquiring linear distribution after scratching or trauma (Koebner’s phenomenon). Although possible anywhere, they typically involve the face (Fig. 3-31), shins, and dorsum of hands. May regress spontaneously, often after an inflammatory flare.

Flat wart: Also called “plane warts” (or verruca plana). Flat and flesh-colored papules, >1–5 mm in size. Smooth or slightly hyperkeratotic, they may number just a few or in the hundreds, at times becoming grouped or confluent, and often acquiring linear distribution after scratching or trauma (Koebner’s phenomenon). Although possible anywhere, they typically involve the face (Fig. 3-31), shins, and dorsum of hands. May regress spontaneously, often after an inflammatory flare.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

109 How does SCC present?

In a myriad of morphologic variants, although typically as a scaly, erythematous, and hyperkeratotic plaque, often with superficial ulceration and no defined translucent border (Fig. 3-32).

110 Where in the skin does SCC originate?

From keratinocytes located in the epidermis, just above the basal layer.

117 What are the causes of skin tags?

Unknown. Proposed etiologies include:

Frequent irritation: Hence, the predilection for intertriginous areas, especially in obese patients

Frequent irritation: Hence, the predilection for intertriginous areas, especially in obese patients

Human papilloma virus (HPV): Frequently cultured in skin tag biopsies, suggesting at least a co-factor role

Human papilloma virus (HPV): Frequently cultured in skin tag biopsies, suggesting at least a co-factor role

Paraneoplastic: Acrochordons may coexist with various neoplasms, especially gastrointestinal and renal, suggesting a role for tumor-secreted growth hormones. Still, the association with colonic polyps is controversial at best.

Paraneoplastic: Acrochordons may coexist with various neoplasms, especially gastrointestinal and renal, suggesting a role for tumor-secreted growth hormones. Still, the association with colonic polyps is controversial at best.

Hormonal imbalances: Hyperestrogenemia and hyperprogesteronemia of pregnancy, the high growth hormone levels of acromegaly, and the hyperinsulinemia of type 2 diabetes

Hormonal imbalances: Hyperestrogenemia and hyperprogesteronemia of pregnancy, the high growth hormone levels of acromegaly, and the hyperinsulinemia of type 2 diabetes

Solid Lesions: White

120 How does vitiligo present?

As milky white, nonscaly, and sharply demarcated macules and patches of variable size (Fig. 3-33). These are often symmetric, and commonly involving areas of repeated trauma, such as elbows, ventral wrists, knees, axillae, dorsal hands, and feet. Other targets include mucous membranes and periorificial sites (eyes, nose, ears, lips, gums, genitals, areolas, and nipples). Lesions eventually increase in number and become confluent, taking on bizarre shapes. They may also appear at sites of injury (koebnerization). Localized vitiligo (i.e., restricted to one area) is less common.

121 What are the other associated cutaneous findings?

Prematurely gray hair, piebaldism (see question 122), halo nevi, alopecia areata, and ocular abnormalities, such as chorioretinitis, retinal pigmentary abnormalities, and iritis. The scalp is the hair most frequently involved, followed by eyebrows, pubis, and axillae. Vitiligo of the scalp usually presents as a localized patch of white or gray hair, but total scalp depigmentation (leukotrichia) may also occur, usually indicating low likelihood of repigmentation.

123 What are the characteristics of piebaldism?

Eighty to ninety percent of individuals have a white forelock, typically from birth. The central frontal scalp can also be permanently white, as may be eyebrow and eyelash hair. Finally, white spots may occur on the face, trunk, and extremities. Piebaldism is one of the cutaneous signs of Waardenburg’s syndrome, along with heterochromia of irides, lateral displacement of inner canthi, and deafness (see Chapter 4, questions 106 and 107).

126 What are the other clinical presentations of vitiligo?

Segmental vitiligo: Characterized by unilateral depigmented macules and patches in a dermatomal or quasi-dermatomal distribution. It generally has a stable course.

Segmental vitiligo: Characterized by unilateral depigmented macules and patches in a dermatomal or quasi-dermatomal distribution. It generally has a stable course.

Focal vitiligo: One or more pale macules in an area that is single but not segmental

Focal vitiligo: One or more pale macules in an area that is single but not segmental

Universal vitiligo: It results in total or nearly total body involvement.

Universal vitiligo: It results in total or nearly total body involvement.

Solid Lesions: Brown

133 What are the causes of AN?

Obesity and insulin resistance: Lesions are weight dependent and may completely regress with slimming.

Obesity and insulin resistance: Lesions are weight dependent and may completely regress with slimming.

Congenital syndromes: Typical of young women with type A or type B syndromes. The type A is also referred to as HAIR-AN syndrome (HyperAndrogenemia, Insulin Resistance, and AN syndrome). It affects primarily young African-American women, with polycystic ovaries, high testosterone levels, and signs of virilization (hirsutism and clitoral hypertrophy). The type B syndrome occurs instead in women with uncontrolled diabetes, ovarian hyperandrogenism, or an autoimmune disease (such as systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, or Hashimoto thyroiditis). Anti-insulin receptor antibodies are often present.

Congenital syndromes: Typical of young women with type A or type B syndromes. The type A is also referred to as HAIR-AN syndrome (HyperAndrogenemia, Insulin Resistance, and AN syndrome). It affects primarily young African-American women, with polycystic ovaries, high testosterone levels, and signs of virilization (hirsutism and clitoral hypertrophy). The type B syndrome occurs instead in women with uncontrolled diabetes, ovarian hyperandrogenism, or an autoimmune disease (such as systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, or Hashimoto thyroiditis). Anti-insulin receptor antibodies are often present.

Drug reaction: Due to nicotinic acid, insulin, pituitary extract, systemic corticosteroids, and diethylstilbestrol

Drug reaction: Due to nicotinic acid, insulin, pituitary extract, systemic corticosteroids, and diethylstilbestrol

136 What about congenital nevi?

They are nevi that are present at birth or soon thereafter. They are probably hamartomas, since they contain many skin elements, but a predominance of melanocytes. Large congenital nevi have a low (5%) but real risk for malignant transformation into melanoma. Hence, the need for prophylactic excision. In a rare autosomal dominant condition, family members acquire with time many large nevi, sometimes more than 100 (see FAMMM, discussed in question 141).

137 List and describe the different types of common nevi (moles).

Melanocytic nevi are classified according to histology:

Junctional nevus: Usually a macule or thinly raised papule with well-circumscribed borders and homogeneous brown to black pigment. Cells are located in the dermoepidermal junction.

Junctional nevus: Usually a macule or thinly raised papule with well-circumscribed borders and homogeneous brown to black pigment. Cells are located in the dermoepidermal junction.

Compound nevus: A raised papule, brown or tan and often lighter than a junctional nevus. Pigmentation and border are even, and cells are at the dermoepidermal junction/upper dermis.

Compound nevus: A raised papule, brown or tan and often lighter than a junctional nevus. Pigmentation and border are even, and cells are at the dermoepidermal junction/upper dermis.

(Intra-) Dermal nevus: Also a papule, usually dome-shaped, pedunculated or warty-surfaced. Cells are in the dermis. Color is brown or even flesh-like, since melanin is often lacking.

(Intra-) Dermal nevus: Also a papule, usually dome-shaped, pedunculated or warty-surfaced. Cells are in the dermis. Color is brown or even flesh-like, since melanin is often lacking.

139 What are atypical or dysplastic nevi (Clark nevi)?

They are acquired variants typical of families of northern European descent, with fair skin, light-colored hair, freckles, and other Celtic features. The United Kingdom, Netherlands, Germany, and occasionally Poland and Russia are the most affected countries. Patients present with hundreds of relatively broad lesions that are flat or thinly papular. The more numerous the nevi, the greater the likelihood of melanoma (see discussion on familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma in question 141). Still, dysplastic nevi are just a marker for risk, and not necessarily a precursor. Hence, removal of all dysplastic nevi may not really alter the risk.

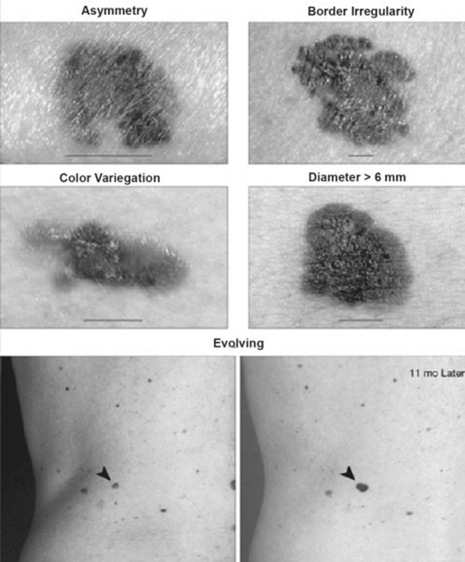

149 What is the ABCD(E) checklist?

A commonly used acronym for identifying the warning signs of malignant melanoma. Developed in 1985, it considers a lesion suspicious when it has more than one of the five following features (see Fig. 3-34):

A = Asymmetry (if the lesion is bisected, one half is not identical to the other half)

A = Asymmetry (if the lesion is bisected, one half is not identical to the other half)

B = Border irregularity (a border that is uneven or ragged as opposed to smooth and straight)

B = Border irregularity (a border that is uneven or ragged as opposed to smooth and straight)

C = Color variegation (more than one shade of pigment)

C = Color variegation (more than one shade of pigment)

D = Diameter increase (defined as a diameter greater than 6 mm)

D = Diameter increase (defined as a diameter greater than 6 mm)

A suggested addition to this list is a final E, for Elevation above the skin surface; however, since elevation is also a feature of many benign nevi, E is often excluded.

A suggested addition to this list is a final E, for Elevation above the skin surface; however, since elevation is also a feature of many benign nevi, E is often excluded.

153 How good is the 7-point checklist?

Several studies have found sensitivity of 79–100% and specificity of 30–37%.

155 What are the major clinical-histopathologic types of melanoma?

Superficial spreading melanoma: The most common subtype (>70% of cases) and the one most frequently found near existing nevi. Onset is during the third to fifth decade, usually over the back of men, legs of women, and trunk of both genders. Lesions are flat or slightly raised, brown, variegated (with black, blue, pink, or white discoloration), >6 mm in diameter, and with irregular borders.

Superficial spreading melanoma: The most common subtype (>70% of cases) and the one most frequently found near existing nevi. Onset is during the third to fifth decade, usually over the back of men, legs of women, and trunk of both genders. Lesions are flat or slightly raised, brown, variegated (with black, blue, pink, or white discoloration), >6 mm in diameter, and with irregular borders.

Nodular melanoma: 15–30% of all melanomas. It presents as a papule or dome-shaped nodule, on legs and trunk, and black or brown-to-bluish in color, even though it may also be amelanotic. It often grows rapidly over just a few months, often with ulceration and bleeding, especially after minor trauma. It originates at the dermoepidermal junction, growing vertically into the dermis with little radial extension.

Nodular melanoma: 15–30% of all melanomas. It presents as a papule or dome-shaped nodule, on legs and trunk, and black or brown-to-bluish in color, even though it may also be amelanotic. It often grows rapidly over just a few months, often with ulceration and bleeding, especially after minor trauma. It originates at the dermoepidermal junction, growing vertically into the dermis with little radial extension.

Lentigo maligna: An in situ (i.e., intraepithelial) precursor of lentigo maligna melanoma. This presents as a flat and relatively large (>3 cm) hyperpigmented area with variegated pigment and an irregular border, commonly located on sun-exposed areas, especially head, neck, and arms. Late occurring (fifth and sixth decades), it exists for 10–15 years before undergoing malignant transformation. This is nonetheless rare (estimated 5–8%) and usually heralded by new brown-to-black macular pigmentation or raised blue-black nodules. Growth is radial. Often called Hutchinson’s freckle from the English surgeon who also described the Hutchinson’s triad of congenital syphilis.

Lentigo maligna: An in situ (i.e., intraepithelial) precursor of lentigo maligna melanoma. This presents as a flat and relatively large (>3 cm) hyperpigmented area with variegated pigment and an irregular border, commonly located on sun-exposed areas, especially head, neck, and arms. Late occurring (fifth and sixth decades), it exists for 10–15 years before undergoing malignant transformation. This is nonetheless rare (estimated 5–8%) and usually heralded by new brown-to-black macular pigmentation or raised blue-black nodules. Growth is radial. Often called Hutchinson’s freckle from the English surgeon who also described the Hutchinson’s triad of congenital syphilis.

Lentigo maligna melanoma: 4–15% of all melanomas. Almost exclusive of sun-damaged areas of the elderly. Large in size (>3 cm), it typically grows slowly over a period of many years. More variegated in color than lentigo maligna.

Lentigo maligna melanoma: 4–15% of all melanomas. Almost exclusive of sun-damaged areas of the elderly. Large in size (>3 cm), it typically grows slowly over a period of many years. More variegated in color than lentigo maligna.

Acrolentiginous melanoma: The rarest in whites (2–8%), but the most common in dark-skinned groups (African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics), in whom it accounts for 29–72% of all melanomas. Because of delayed diagnosis, it carries a worse outcome. It occurs on palms, soles, or beneath the nail plate, presenting as one or more dark papules against a pigmented and unevenly speckled background—often resembling lentigo maligna melanoma. The subungual variety may occur as diffuse nail discoloration, or a longitudinal pigmented band within the nail plate. A hallmark finding is pigment spreading to proximal or lateral nail folds (Hutchinson’s sign).

Acrolentiginous melanoma: The rarest in whites (2–8%), but the most common in dark-skinned groups (African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics), in whom it accounts for 29–72% of all melanomas. Because of delayed diagnosis, it carries a worse outcome. It occurs on palms, soles, or beneath the nail plate, presenting as one or more dark papules against a pigmented and unevenly speckled background—often resembling lentigo maligna melanoma. The subungual variety may occur as diffuse nail discoloration, or a longitudinal pigmented band within the nail plate. A hallmark finding is pigment spreading to proximal or lateral nail folds (Hutchinson’s sign).

Signs of Sun Damage

157 What are the characteristic signs of sun damage?

Solar lentigo (lentigines): From the Latin lentigo (lentil), these are sun-induced, well-circumscribed, light brown or tan macules that resemble a freckle, except for regular border, microscopic proliferation of the rete ridges, and persistence even after the tan or sunburn fades. Typically on sun-exposed areas of the face, hands, and shoulders, they range in size between 5–20 mm. They have no potential for neoplastic degeneration, and yet a lentigo with black, pinhead-sized speckles (lentigo maligna) may degenerate over years into lentigo maligna melanoma.

Solar lentigo (lentigines): From the Latin lentigo (lentil), these are sun-induced, well-circumscribed, light brown or tan macules that resemble a freckle, except for regular border, microscopic proliferation of the rete ridges, and persistence even after the tan or sunburn fades. Typically on sun-exposed areas of the face, hands, and shoulders, they range in size between 5–20 mm. They have no potential for neoplastic degeneration, and yet a lentigo with black, pinhead-sized speckles (lentigo maligna) may degenerate over years into lentigo maligna melanoma.

Freckles: From the Old English freken (ephelis), these are yellowish/brownish sun-induced macules on exposed areas, typical of light-complexioned individuals with red or blond hair. Lesions increase in number after exposure to the sun. The epidermis is microscopically normal, except for increased melanin. A freckle resembles a solar lentigo, except that (1) it appears early in life (lentigines do not occur until mid-adulthood); (2) it is usually smaller (only 1–2 mm in diameter); and (3) it may disappear with time. It has no malignant potential. Still, clustered freckles (especially over lips and fingertips) should raise the possibility of Peutz-Jeghers (see Chapter 6, question 74).

Freckles: From the Old English freken (ephelis), these are yellowish/brownish sun-induced macules on exposed areas, typical of light-complexioned individuals with red or blond hair. Lesions increase in number after exposure to the sun. The epidermis is microscopically normal, except for increased melanin. A freckle resembles a solar lentigo, except that (1) it appears early in life (lentigines do not occur until mid-adulthood); (2) it is usually smaller (only 1–2 mm in diameter); and (3) it may disappear with time. It has no malignant potential. Still, clustered freckles (especially over lips and fingertips) should raise the possibility of Peutz-Jeghers (see Chapter 6, question 74).

Rhytides: From the Greek for wrinkles, these are the familiar skin changes of sun-exposed individuals, such as farmers, fishermen, and ski instructors who do not believe in sunscreen.

Rhytides: From the Greek for wrinkles, these are the familiar skin changes of sun-exposed individuals, such as farmers, fishermen, and ski instructors who do not believe in sunscreen.

Evidence of sun-induced cellular atypia: This includes actinic keratosis and squamous or basal cell carcinoma. Of course, a melanoma is the deadliest of all sun-damage effects.

Evidence of sun-induced cellular atypia: This includes actinic keratosis and squamous or basal cell carcinoma. Of course, a melanoma is the deadliest of all sun-damage effects.

Solid Lesions: Yellow

158 What are the most common yellow lesions of the skin?

Cutaneous xanthomas and necrobiosis lipoidica (see also questions 258 and 259).

165 What are eruptive xanthomas?

Small and red-yellow papules on an erythematous base, typically erupting in crops over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of extremities (more rarely over the face or oral mucosa) (Fig. 3-35). Often pruritic and tender, they usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks. Eruptive xanthomas are associated with hypertriglyceridemia, particularly types I, IV, and V (high very low-density lipoprotein [VLDL] level and chylomicrons), yet they also may occur in secondary hyperlipidemias, especially if related to diabetes.

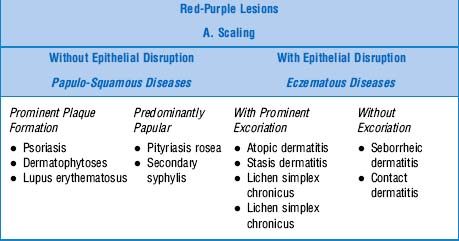

Solid Lesions: Red or Purple—Table 3-4

173 What is the typical clinical course of psoriasis?

One of variable extent and duration, even though usually as a lifelong disease. Spontaneous remissions occur with unpredictable frequency, and patients may move from one clinical form to another. Acute flares may evolve into more severe disease, such as pustular or erythrodermic (see question 174).

174 What are the other clinical presentations of psoriasis?

Psoriasis is a heterogeneous disorder with a spectrum of clinical variants:

Intertriginous (axillary, inframammary, inguinal, perianal): Lack of maceration prevents scales.

Intertriginous (axillary, inframammary, inguinal, perianal): Lack of maceration prevents scales.

Guttate: Sudden explosion of hundreds of small, erythematous, and nonconfluent papules, widely distributed and not very scaly. Palms and soles are rarely affected, and nail changes like pits, ridges, and the oil-drop sign (typical of chronic psoriasis) may be absent. Guttate psoriasis often occurs in young adults and children and may be triggered by a streptococcal infection, as well as by a viral upper respiratory infection. In fact, all psoriatic forms can be exacerbated by infections, especially upper respiratory infections (URIs) by Streptococcus and Staphylococcus.

Guttate: Sudden explosion of hundreds of small, erythematous, and nonconfluent papules, widely distributed and not very scaly. Palms and soles are rarely affected, and nail changes like pits, ridges, and the oil-drop sign (typical of chronic psoriasis) may be absent. Guttate psoriasis often occurs in young adults and children and may be triggered by a streptococcal infection, as well as by a viral upper respiratory infection. In fact, all psoriatic forms can be exacerbated by infections, especially upper respiratory infections (URIs) by Streptococcus and Staphylococcus.

Erythrodermic: Total body erythema with scaling, possibly hypothermia and heart failure

Erythrodermic: Total body erythema with scaling, possibly hypothermia and heart failure

Pustular: The most serious form, presenting in a generalized and systemic fashion, with fever anemia, leukocytosis, erythema, and overlying pustules (Von Zumbusch type). A more localized form involves instead the palms and soles, with no systemic symptoms (Barber type).

Pustular: The most serious form, presenting in a generalized and systemic fashion, with fever anemia, leukocytosis, erythema, and overlying pustules (Von Zumbusch type). A more localized form involves instead the palms and soles, with no systemic symptoms (Barber type).

179 How are dermatophytoses classified?

By the body region involved (Table 3-5). Note that fungal involvement can affect multiple sites. Hence, if you see lesions on the buttocks, always ask, “Can I see your feet?” Almost invariably there will be typical fungal lesions in the fourth web space.

| Disease | Location | Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Tinea capitis | Scalp | Infection of scalp hair. It causes erythematous patches of alopecia and scaling, with broken hair. Kerion celsi, an inflammatory variant, produces tender abscesses with purulent drainage that may result int scarring alopecia. Favus (also termed tinea favosa) is severe tinea capitis with yellow, cup-shaped crusts around infected hair follicles. |

| Tinea corporis | Body | Infection of exposed areas of trunk and extremities. Characterized by circular lesions with central clearing and erythematous/raised edges (ringworm) eventually evolving into annular scaly plaques. May also present with pustules and vesicles. |

| Tinea faciale | Face | Red scaly plaques sometimes lacking central clearing and elevated border. |

| Tinea barbae | Beard | Infection of beard and neck area, characterized by erythema, scaling, and pustules. |

| Tinea cruris (jock itch) | Groin | Infection of groin and pubic region. Causes plaques with central clearing and raised scaly border. On inguinal fold and adjacent skin, but not scrotum. |

| Tinea manus | Hand | Infection of palms and finger webs, usually in association with tinea pedis. Lesions consist of annular plaques on the dorsum of hand, with hyperkeratosis of palms. Scaling and erythema may also be present. Affects only one hand (but often two feet). |

| Tinea pedis | Feet | Infection of interdigital webs, usually third and fourth. Presents with erythema, scaling, fissuring, and maceration (athlete’s foot). Hyperkeratosis and scaling may extend to the sole’s instep. Variations include bilateral moccasin distribution (scaling of soles and lateral surfaces) or vesicopustules on the instep. Onychomycosis may also occur, and is often the portal of entry for other tinea lesions. |

| Tinea unguium (onychomycosis) | Nail | Yellow-brown discoloration of nail plate associated with subungual hyperkeratosis. |

184 Who gets it?

Any age group, although usually 10- to 35-year-olds—women twice more frequently than men.

188 How is pityriasis rosea diagnosed?

190 What are the clinical features of atopic dermatitis?

Erythematous papules and plaques, which at times may be follicular

Erythematous papules and plaques, which at times may be follicular

Vesicles, pustules, weeping, and crusting; usually due to superinfection with herpes or staphylococci

Vesicles, pustules, weeping, and crusting; usually due to superinfection with herpes or staphylococci

Chronic excoriations leading to secondary changes, such as linear erosions and lichenification (thickening and accentuation of skin markings)

Chronic excoriations leading to secondary changes, such as linear erosions and lichenification (thickening and accentuation of skin markings)

191 Describe the distribution of atopic dermatitis lesions.

Infants: Face (especially the cheeks) and extensor surfaces

Infants: Face (especially the cheeks) and extensor surfaces

Children: Hands, feet, antecubital and popliteal fossae

Children: Hands, feet, antecubital and popliteal fossae

Adults: Flexures (including genitalia) but also the face (eyelids and forehead), neck, hands, and feet

Adults: Flexures (including genitalia) but also the face (eyelids and forehead), neck, hands, and feet

Generalized involvement may develop at any age (see Fig. 3-36).

208 How is seborrheic dermatitis diagnosed?

By the typical clinical appearance. Biopsy is nondiagnostic.

Nonscaling Lesions—Table 3-6

Cherry Angiomas

209 What are cherry angiomas?

| Red-Purple Lesions | ||

|---|---|---|

| B. Nonscaling | ||

| Dome-Shaped | Flat-Topped | Drug Reactions |

| Inflammatory Papules | Vascular Reactions | Minor-to-Major |

| • Cherry angiomas | A. Nonpurpuric (Blanchable) | • Morbilliform fine pink papules |

| • Pyogenic granuloma | • Toxic erythema | • Urticaria |

| • Insect bites | • Urticaria | • Vasculitis |

| • Lichen planus | • Erythema multiforme | |

| • Erythema multiforme | • Stevens-Johnson | |

| • Erythema nodosum | • TEN | |

| • Vascular reactions | ||

| B. Purpuric (Nonblanchable) | ||

| • Palpable purpura | ||

| • Miscellaneous petechiae and ecchymotic disease | ||

211 Who gets lichen planus?

Men and women in their 40s; 10% have positive family history, suggesting genetic predisposition.

213 What other sites beside the skin may be involved?

LP can occur on mucous membranes, genitalia, nails (see question 38), and the scalp. The latter can progress to atrophic cicatricial alopecia.

Vascular Reactions

220 How are noninflammatory purpuras classified?

By size, shape, and depth. In this regard, blood extravasations can be divided into four groups:

Petechiae: Superficial, pinpoint (<3 mm), red or purple, nonblanching macules. Mostly located on dependent areas, usually caused by platelet-related issues or vessel disease.

Petechiae: Superficial, pinpoint (<3 mm), red or purple, nonblanching macules. Mostly located on dependent areas, usually caused by platelet-related issues or vessel disease.

Ecchymoses: Larger (>3 mm) and flat, usually due to more significant extravasation. Also known as bruises. They form an initial purple patch, eventually turning yellow and fading.

Ecchymoses: Larger (>3 mm) and flat, usually due to more significant extravasation. Also known as bruises. They form an initial purple patch, eventually turning yellow and fading.

Vibices: Linear purpuric lesions due to scratching

Vibices: Linear purpuric lesions due to scratching

Hematomata: Deeper collections of blood within the skin. They may be fluctuant.

Hematomata: Deeper collections of blood within the skin. They may be fluctuant.

224 What are the characteristics of LCV lesions?

Palpable purpura: The most common cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Lesions are usually on the legs, even though any area can be involved; round; small (1–3 mm in size, but at times coalescing into plaques); palpable (if only barely); and rarely ulcerated (a more common feature of large vessels vasculitis). Subungual splinter hemorrhages also may occur.

Palpable purpura: The most common cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Lesions are usually on the legs, even though any area can be involved; round; small (1–3 mm in size, but at times coalescing into plaques); palpable (if only barely); and rarely ulcerated (a more common feature of large vessels vasculitis). Subungual splinter hemorrhages also may occur.

Urticarial lesions: Of longer duration (often >24 hours) than regular urticarial lesions. Usually resolving with residual pigmentation or ecchymosis. More burning than pruritic.

Urticarial lesions: Of longer duration (often >24 hours) than regular urticarial lesions. Usually resolving with residual pigmentation or ecchymosis. More burning than pruritic.

226 What are the causes of cutaneous vasculitis?

It depends on the patient’s age:

1. In children the most common cause is Henoch-Schönlein purpura, followed at a great distance by leukocytoclastic hypersensitivity (i.e., drug reaction).

2. In adults, cutaneous vasculitis is often due to immune complexes, although other autoantibodies can do it, too. Yet, 30–50% of all cases are idiopathic. The rest are caused by:

Drugs, especially antibiotics (particularly beta-lactams), diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but also foods or food additives.

Drugs, especially antibiotics (particularly beta-lactams), diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but also foods or food additives. Infections, including upper respiratory tract infections (particularly beta-hemolytic streptococcal), viral hepatitis (especially C, probably through the presence of cryoglobulins), HIV, and endocarditis. Vasculitis usually postdates the infection.

Infections, including upper respiratory tract infections (particularly beta-hemolytic streptococcal), viral hepatitis (especially C, probably through the presence of cryoglobulins), HIV, and endocarditis. Vasculitis usually postdates the infection. Collagen vascular diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, and lupus erythematosus. Vasculitis often denotes active disease and possibly poorer prognosis. Note that cutaneous vasculitis is rarely seen in patients with involvement of larger vessels, such as polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss syndrome, or Wegener’s syndrome.

Collagen vascular diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, and lupus erythematosus. Vasculitis often denotes active disease and possibly poorer prognosis. Note that cutaneous vasculitis is rarely seen in patients with involvement of larger vessels, such as polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss syndrome, or Wegener’s syndrome.Miscellaneous Disorders

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

227 What are the major types of Kaposi’s sarcoma? Describe each.

Classic (traditional): Now relatively rare, this is the KS of shins or feet of older men of either Mediterranean or Eastern European descent (Ashkenazi Jews). It begins as purplish papules slowly progressing to plaques. Rarely fatal. In fact, most patients die with KS rather than of KS.

Classic (traditional): Now relatively rare, this is the KS of shins or feet of older men of either Mediterranean or Eastern European descent (Ashkenazi Jews). It begins as purplish papules slowly progressing to plaques. Rarely fatal. In fact, most patients die with KS rather than of KS.

Epidemic (AIDS-associated): Present in more than one third of AIDS patients. Lesions are more varied and widespread than in the classic form, ranging from macules to papules, to plaques or ulcers, all red-purple in color (Fig. 3-37). Mean survival is 15–24 months, although antiretroviral therapy has extended it. Visceral involvement is common, including genital, oral, GI, and pulmonary sites.

Epidemic (AIDS-associated): Present in more than one third of AIDS patients. Lesions are more varied and widespread than in the classic form, ranging from macules to papules, to plaques or ulcers, all red-purple in color (Fig. 3-37). Mean survival is 15–24 months, although antiretroviral therapy has extended it. Visceral involvement is common, including genital, oral, GI, and pulmonary sites.

Endemic (African): Cutaneous and/or lymphatic. Common (10% of all cancers), aggressive, 15:1 male-to-female ratio, and possible in children. Endemic in Uganda, Congo, and Zambia.

Endemic (African): Cutaneous and/or lymphatic. Common (10% of all cancers), aggressive, 15:1 male-to-female ratio, and possible in children. Endemic in Uganda, Congo, and Zambia.

Iatrogenic: From immunosuppression, may regress with its termination. Often with GI bleeding.

Iatrogenic: From immunosuppression, may regress with its termination. Often with GI bleeding.

228 What is the presentation of KS?

Usually begins as bilateral and symmetric discrete skin patches, red or purple in color but occasionally violaceous, typically involving the lower extremities. These eventually become elevated, evolving into spongy nodules and plaques (localized nodular form).

Usually begins as bilateral and symmetric discrete skin patches, red or purple in color but occasionally violaceous, typically involving the lower extremities. These eventually become elevated, evolving into spongy nodules and plaques (localized nodular form).

May also present in a locally aggressive form, either as a large infiltrating mass or multiple cone-shaped friable tumors, firmly adhering to underlying anatomic structures, like bone.

May also present in a locally aggressive form, either as a large infiltrating mass or multiple cone-shaped friable tumors, firmly adhering to underlying anatomic structures, like bone.

Finally, it may spare the skin and present with visceral involvement (including lymph nodes).

Finally, it may spare the skin and present with visceral involvement (including lymph nodes).

Course ranges from indolent (if limited to skin) to fulminant (if affecting multiple internal organs).

Course ranges from indolent (if limited to skin) to fulminant (if affecting multiple internal organs).

233 What are the cutaneous manifestations of LE?

Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE)

Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE)

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE)

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE)

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), also called discoid lupus (DLE)

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), also called discoid lupus (DLE)

These are histopathologically similar but clinically very different.

237 What laboratory studies are positive in ACLE?

The same studies that are positive in SLE:

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are invariably present (95% sensitivity). They have, however, low specificity, even though they are much less common in dermatomyositis, a condition that can otherwise mimic LE.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are invariably present (95% sensitivity). They have, however, low specificity, even though they are much less common in dermatomyositis, a condition that can otherwise mimic LE.

Anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies are present in 60–80% of ACLE patients. More specific for SLE. They may also correlate with the degree of activity of lupus in general, and with the level of nephritis.

Anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies are present in 60–80% of ACLE patients. More specific for SLE. They may also correlate with the degree of activity of lupus in general, and with the level of nephritis.

Anti-Sm antibodies are very specific for SLE. Hence, if negative, they exclude underlying systemic involvement.

Anti-Sm antibodies are very specific for SLE. Hence, if negative, they exclude underlying systemic involvement.

241 What is the association with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE)?

Some SCLE patients can have lesions of DLE. Some may even develop small vessel vasculitis.

Syphilis

252 What are the primary lesions of syphilis?

Primary syphilis: Classic lesion is the chancre, which occurs within 3 weeks at the site of treponemal penetration—usually the penis or scrotum in men (70%) and the vulva, cervix, or perineum in women (50%), but also any body region in both genders. The lesion begins as a 1–2 cm, single, round, and firm papule, rapidly evolving into a painless nonbleeding ulcer (the chancre) with raised indurated borders. Induration is key. In fact, the lesion can almost be flipped between fingers, as if it were a button under the skin. Chancres are highly infectious, but heal in 4–8 weeks—with or without therapy. Painless regional lymphadenopathy is common.

Primary syphilis: Classic lesion is the chancre, which occurs within 3 weeks at the site of treponemal penetration—usually the penis or scrotum in men (70%) and the vulva, cervix, or perineum in women (50%), but also any body region in both genders. The lesion begins as a 1–2 cm, single, round, and firm papule, rapidly evolving into a painless nonbleeding ulcer (the chancre) with raised indurated borders. Induration is key. In fact, the lesion can almost be flipped between fingers, as if it were a button under the skin. Chancres are highly infectious, but heal in 4–8 weeks—with or without therapy. Painless regional lymphadenopathy is common.

Secondary syphilis: A mucocutaneous eruption that occurs 2–10 weeks after the primary chancre, and becomes most florid at 3–4 months from infection. If untreated, it resolves in the same amount of time, even though relapses may occur. It may be so subtle that 25% of patients are unaware. Lesions are 5–10 mm macules, pale-red to pink, circular or ring-shaped, covered by sparse scaling, and diffusely distributed on the trunk and proximal extremities. Over days to weeks, they evolve into red papules, which are often necrotic and more widely distributed. Lesions can also affect the palms, soles, and hair follicles, thus resulting in patchy alopecia. One tenth of all patients develop superficial mucosal erosions (of the palate, pharynx, larynx, glans penis, vulva, and even anal canal and rectum). These are circular, silver-gray, and with a red areola. They are highly infectious. Lymphadenopathy is common, as are constitutional symptoms (malaise, anorexia, aching pains, fatigue, fever, headache, and some degree of neck stiffness).

Secondary syphilis: A mucocutaneous eruption that occurs 2–10 weeks after the primary chancre, and becomes most florid at 3–4 months from infection. If untreated, it resolves in the same amount of time, even though relapses may occur. It may be so subtle that 25% of patients are unaware. Lesions are 5–10 mm macules, pale-red to pink, circular or ring-shaped, covered by sparse scaling, and diffusely distributed on the trunk and proximal extremities. Over days to weeks, they evolve into red papules, which are often necrotic and more widely distributed. Lesions can also affect the palms, soles, and hair follicles, thus resulting in patchy alopecia. One tenth of all patients develop superficial mucosal erosions (of the palate, pharynx, larynx, glans penis, vulva, and even anal canal and rectum). These are circular, silver-gray, and with a red areola. They are highly infectious. Lymphadenopathy is common, as are constitutional symptoms (malaise, anorexia, aching pains, fatigue, fever, headache, and some degree of neck stiffness).

Benign tertiary syphilis: The end-result of the untreated resolution of secondary lesions. It develops 3–10 years after initial infection. Its typical lesion is the gumma, which may occur anywhere, although more often in areas of trauma. Cutaneous gummas are nontender and rubbery nodules that range in diameter from less than 1 cm to several centimeters and can evolve into papulosquamous or ulcerative lesions. These usually heal with noncontractile scarring, forming characteristic circles and arcs with peripheral hyperpigmentation. Only one third of patients develop tertiary syphilis—divided among cutaneous gummas (16%), cardiovascular involvement (9.6%), and central nervous system disease (6.5%).