2 THE SHOULDER

Applied Anatomy

ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT

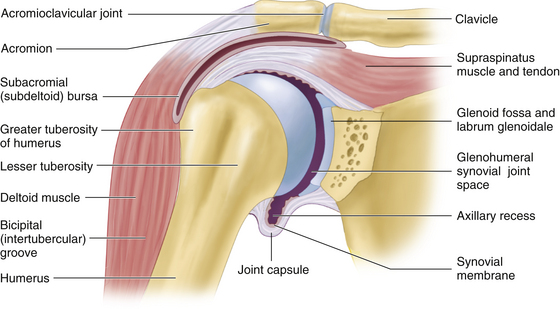

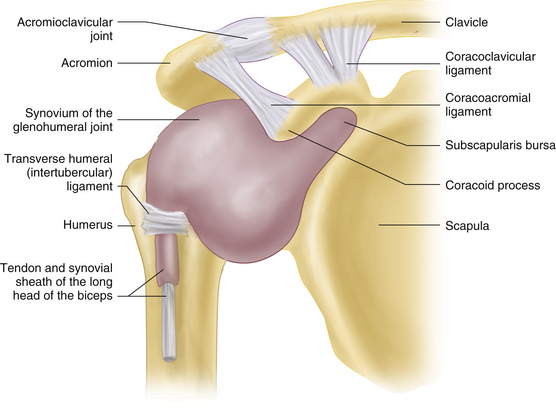

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is a spheroidal joint between the lateral end of the clavicle and the acromion process of the scapula (Figure 2-1). A small, intraarticular fibro cartilaginous disk divides the joint into two compartments. A subcutaneous, noncommunicating bursa may be present over the joint. The stability of the AC joint depends on the capsule and the superior and inferior AC ligaments. The coracoclavicular ligament (conoid and trapezoid parts) extends between the distal clavicle and the coracoid process of the scapula (Figure 2-2). It suspends the scapula, stabilizes both the clavicle and the scapula, and maintains a close relation between the two bones during shoulder movements, thus limiting scapular rotation around the AC joint. The AC and SC joints augment the range of shoulder movements, particularly abduction and rotation. The joints also allow slight axial rotation of the clavicle, as well as elevation/depression and forward/backward thrusting of the shoulder.

GLENOHUMERAL JOINT

The glenohumeral (GH) joint, the main articulation of the shoulder complex, is a multiaxial, ball-and-socket synovial articulation between the glenoid fossa of the scapula and the humeral head (Figure 2-1). The lax articular capsule and the small area of contact between the shallow glenoid fossa and the spheroidal humeral head permit a wide range of motion. The stability of the joint depends on a number of static and dynamic stabilizers. Static stabilizers include negative intraarticular pressure; GH bone geometry; the capsule; the glenoid labrum; the superior, middle, and inferior GH ligaments; and the coracohumeral ligament. The capsule, which fuses in part with the tendons of the rotator cuff, has two apertures: one for the long biceps tendon (origin from the supraglenoid tubercle) and one for the subscapularis bursa. The labrum, a ring of fibrocartilage that surrounds and deepens the glenoid cavity, contributes significantly to GH joint stability. Through a bumper effect, it functions as a “chock block” to prevent translational forces.

The coracoacromial arch—made up of the coracoid process, coracoacromial ligament, and acromion—acts as a protective, secondary socket for the humeral head, under which the rotator cuff tendons and long biceps tendon glide, with the subacromial bursa lying in between. The arch prevents upward displacement of the humeral head and protects the head and rotator cuff from direct trauma. The undersurface of the acromion is commonly flat (type 1); less frequently, it is downwardly curved (type 2) or hooked (type 3), but these conditions are more commonly associated with subacromial impingement.

The synovium of the shoulder lines the inner surface of the capsule. It has two extracapsular outpouchings, the tenosynovial sheath of the long biceps tendon and the bursa beneath the subscapularis tendon (Figure 2-2). A communicating infraspinatus bursa is sometimes present. The subcoracoid bursa lies between the shoulder capsule and the coracoid process, but it rarely communicates with the joint.

SCAPULOTHORACIC MOVEMENTS

The so-called scapulothoracic articulation is not a true joint but functions as an integral part of the shoulder complex. The scapula, which is connected to the posterior aspect of the chest wall by the axioappendicular muscles, provides the origin for the rotator cuff muscles and deltoid, and the trapezius inserts into its superior aspect. Scapulothoracic movements that include rotation, elevation, depression, protrusion, retraction, and circumduction are important for the normal functioning of the shoulder. The scapulothoracic bursa is located between the serratus anterior and the chest wall, just medial to the inferior angle of the scapula.

NERVE SUPPLY TO THE SHOULDER JOINT

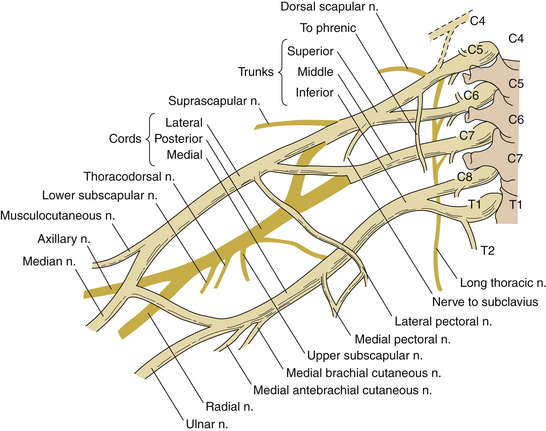

The shoulder joint derives its nerve supply from three branches of the brachial plexus: suprascapular, axillary, and lateral pectoral nerves (C5/C6). The axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery pass through the quadrilateral or quadrangular space, which lies inferoposterior to the GH joint, bounded by the teres minor superiorly, the teres major inferiorly, the long head of triceps medially, and the shaft of the humerus laterally (Figure 2-3).

SHOULDER PAIN AND HISTORY TAKING

Shoulder pain is a common symptom of diverse causes (Table 2-1). The pain may originate in the GH or AC joint or in periarticular structures, or it may be referred from the cervical spine, brachial plexus, thoracic outlet, or infradiaphragmatic structures. Important points in the history include age, hand dominance, occupational and sport activities involving heavy lifting or overhead repetitive movements, history of trauma, onset, location, character, duration, radiation of the shoulder pain, aggravating and relieving factors, presence of night pain, and the effect on shoulder function. Associated symptoms—shoulder stiffness, restriction of movement, grinding, clicking, instability, or weakness—may also provide useful diagnostic clues.

| Articular Causes |

| GH and AC arthritis: OA, RA, PsA, trauma, infection, crystal-induced |

| Ligamentous and labral lesions |

| GH and AC joint instability |

| Osseous: fracture, osteonecrosis, neoplasm, infection |

| Periarticular Causes |

| Chronic impingement and rotator cuff tendinitis |

| Bicipital tendinitis |

| Rotator cuff and long biceps tendon tears |

| Subacromial bursitis |

| Adhesive capsulitis |

| Neurological Lesions About the Shoulder |

| Thoracic outlet syndrome |

| Acute brachial plexus neuritis |

| Quadrilateral space syndrome |

| Suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome |

| Cervical radiculopathy |

| Referred and Miscellaneous Causes |

| Angina pectoris |

| Diaphragmatic and infradiaphragmatic disorders: pericarditis, pleurisy, gallbladder disease, subphrenic abscess |

| Axillary artery or vein thrombosis |

| Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome and shoulder–hand syndrome |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica, myositis |

| Diffuse fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome |

| Somatization disorder and psychogenic regional pain syndrome |

AC, acromioclavicular; GH, glenohumeral; OA, osteoarthritis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Common Disorders of the Shoulder

ROTATOR CUFF PATHOLOGY

In young persons, rotator cuff tendinopathy is often caused by a sport-related injury; for example, from use of the arm in an overhead position in baseball, racquetball, tennis, or swimming. In older individuals, an antecedent history of repetitive movements above the shoulder level or of strenuous or unaccustomed arm activity is common. Symptoms include aching pain in the shoulder, lateral aspect of the upper arm, and deltoid insertion; pain with movement, particularly abduction and internal rotation; night pain when rolling onto the affected side; restriction of shoulder movements; and sometimes weakness caused by a rotator cuff tear. The patient typically experiences shoulder pain on active abduction, especially between 60° and 120°, and difficulty with overhead work, lifting, or reaching behind the back when dressing. Clinical findings include a painful arc between 60° to 120° of abduction, limitation of active movement by pain, and tenderness localized to the rotator cuff and greater tuberosity. The supraspinatus test, Neer impingement test, Neer impingement sign, and Hawkins impingement sign (see Special Tests of Shoulder, p. 13) are often positive.

ADHESIVE CAPSULITIS

Criteria for diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis include an insidious onset, true shoulder pain lasting longer than 3 months, night pain, painful restriction of all active and passive movements with external rotation reduced to less than 50% of normal, and a normal radiologic appearance. Although 90% of patients recover some use of the extremity within 12 to 18 months, about 40% develop more prolonged pain, restriction of movement, and functional disability.

NEUROLOGIC LESIONS ABOUT THE SHOULDER

Suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome is characterized by deep aching pain in the upper posterior aspect of the scapula, made worse by shoulder adduction, and by weakness of abduction and external rotation. It is caused by compression of the suprascapular nerve in the suprascapular notch, beneath the suprascapular or transverse scapular ligament, or by a ganglion or lipoma. It can also result from repetitive trauma due to excessive overhead movements. Local tenderness over the suprascapular notch and variable weakness and wasting of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles are the main findings.

Physical Examination

RANGE OF MOTION

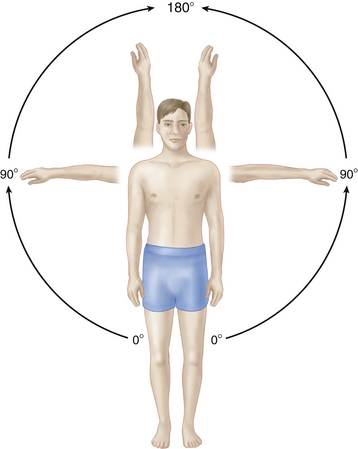

Shoulder abduction involves synchronous movements of the GH, SC, and AC joints and rotation of the scapula on the chest wall. The initial 30° of abduction, achieved by contraction of the supraspinatus, takes place at the GH joint with little movement of the scapula. Beyond 30°, an approximate 2:1 ratio exists between GH and scapular movements. The combined movement is referred to as the scapulohumeral rhythm. Normal shoulder abduction is 180° (Figure 2-4).

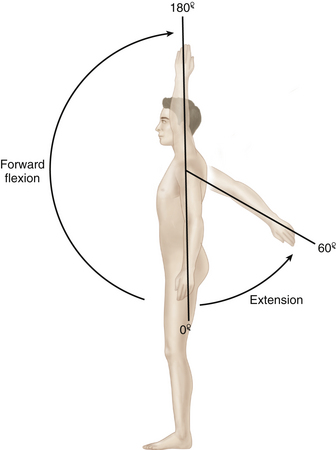

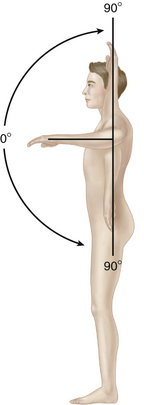

To test forward flexion of the shoulder (deltoid, coracobrachialis, and biceps muscles; normal range 180°; Figure 2-5), the patient flexes the joint with the elbow extended, while the examiner stabilizes the scapula with one hand and resists forward flexion with the other hand placed over the upper arm. To test extension (latissimus dorsi, teres major, and deltoid muscles; normal range 60°; see Figure 2-5), the patient extends the shoulder, with the forearm fully pronated, while the examiner immobilizes the scapula and resists extension. With the shoulder abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed at 90°, the normal range of internal and external rotation is 90° each (Figure 2-6). With the elbow placed at the side at the waist, the normal range of external rotation is about 45° to 90°, and internal rotation is about 55° to 80° before its motion is stopped by the body; it may be as much as 120° if the patient can reach behind the back to touch the inferior angle of the opposite scapula (Apley scratch test). This is a functional movement required for daily activities, such as reaching a back pocket, scratching the back, or cleansing the perineum.

SPECIAL TESTS

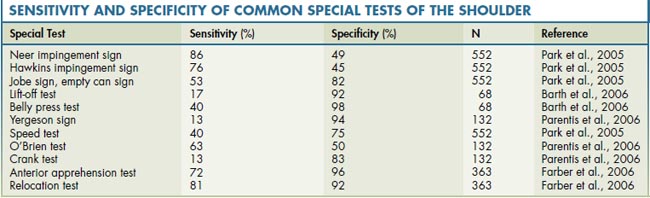

Special tests for the shoulder are plentiful. These tests are designed to elicit evidence of impingement, rotator cuff dysfunction, superior labral anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions, irritation of the long head of the biceps, and shoulder instability. The sensitivity and specificity of each of these tests has been an area of much study. A recent meta-analysis on this topic reveals significant variability in the sensitivity and specificity of these tests, depending on the population studied and the pretest probability of the condition in the population being studied. A summary of these findings is presented in Table 2-2.

Tests for Shoulder Impingement

The Neer impingement sign is elicited with the patient seated and the examiner standing. Scapular rotation is prevented by one hand, as the other elevates the patient’s arm midway between abduction and flexion. In a positive test, the patient experiences pain in the overhead position near the end of shoulder elevation, as the greater tuberosity impinges against the acromion (Figure 2-7). The pain can be relieved by subacromial injection of 5–10 mL of 1.0% lidocaine (Neer impingement test).

In the Hawkins impingement sign, the humerus is forward flexed to 90° and internally rotated, while the examiner’s other hand restricts scapular movements (Figure 2-8). This causes impingement of the greater tuberosity against the anterior acromion with reproduction of the patient’s symptoms. In patients with impingement and supraspinatus tendinitis or a tear, the Jobe test, supraspinatus isolation test, or empty can sign is positive: pain is elicited on resisted elevation of the arm to 90° midway between abduction and forward flexion, with the thumb pointing downward in internal rotation (Figure 2-9).

In subcoracoid impingement, there is impingement of the rotator cuff between the lesser tuberosity and the lateral aspect of the coracoid process during abduction and internal rotation. It commonly occurs in the throwing athlete. This type of impingement is associated with anteromedial shoulder pain and a positive Gerber subcoracoid test: painful restriction of internal rotation when the shoulder is abducted or flexed 90°, because this position produces the narrowest coracohumeral distance. Combined forward flexion, internal rotation, and cross-arm adduction (coracoid impingement test) also causes pain. The coracoid impingement test differs from the O’Brien active compression test for superior labral tears, in which the patient actively resists the examiner while performing the maneuver. The pain of subcoracoid impingement can be relieved by a lidocaine injection between the humeral head and the coracoid process.

Tests of the Rotator Cuff

The supraspinatus (suprascapular nerve) is tested with the shoulder abducted 90°, flexed 30°, and internally rotated with the thumb pointing downward, while the examiner fixes the scapula with one hand and resists abduction with the other hand. This is known as the Jobe test, the supraspinatus isolation test, or the empty can sign (see Figure 2-9). In complete supraspinatus tears, the drop-arm test is positive: the patient is unable to actively maintain 90° of passive shoulder abduction or to slowly lower the arm to the side. With a partial supraspinatus tear, there is wasting and weakness of the supraspinatus muscle. The supraspinatus test, Neer impingement sign, and Hawkins impingement sign are often positive.

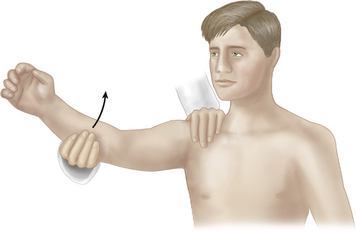

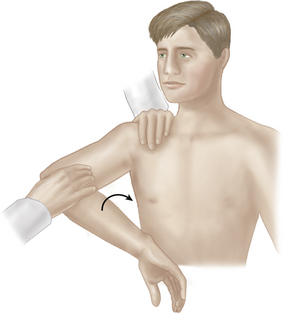

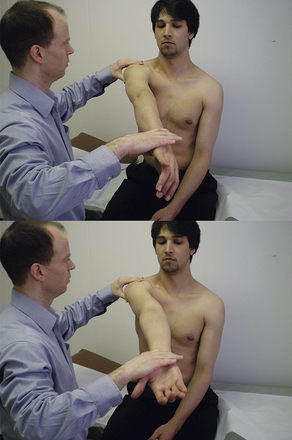

Infraspinatus and teres minor tears are associated with weakness of external rotation and a positive external rotation lag sign (ERLS): with the patient sitting, elbow 90° flexed, and the shoulder held by the examiner at 20° to 90° abduction and maximal external rotation, the patient is asked to actively maintain the position of external rotation as the examiner releases the wrist, and a “lag” or “angular drop” occurs. An alternative maneuver is the Hornblower Test. This test involves external rotation with the shoulder in 90° of abduction in the scapular plane. The elbow is flexed 90°, and the patient externally rotates against the resistance of the examiner’s hand (Figure 2-10). Weakness of external rotation in this position constitutes a positive test.

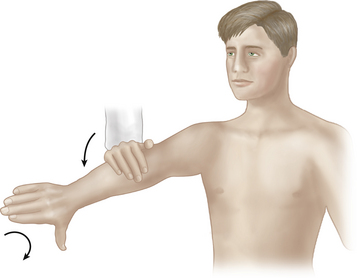

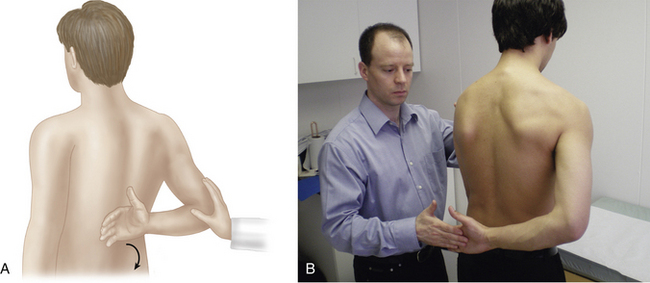

Subscapularis tears are associated with weakness of internal rotation and a positive subscapularis lift-off test: after maximal internal rotation of the shoulder with the dorsum of the hand held against the inferior aspect of scapula, the patient is unable to lift the hand off his back (Figure 2-11). A subscapularis tear is also detected by the belly press test (Figure 2-12). The patient presses the abdomen with the palm of the hand (internal rotation), and if the subscapularis is intact, the patient can maintain pressure without the elbow dropping backward; if there is a subscapularis tear, maximal internal rotation cannot be maintained, and the elbow drops back behind the trunk (positive belly press test). The patient exerts pressure on the abdomen by extending the shoulder rather than by internally rotating it. The test is particularly useful in those patients with restricted internal rotation who cannot place the hand behind the back to perform the lift-off test.

Tests for Labral Tears and Biceps Tendon Pathology

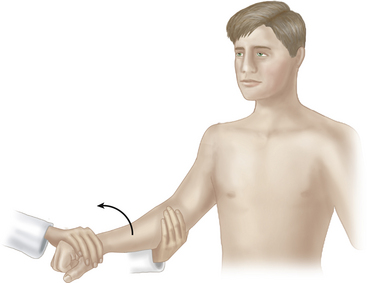

In bicipital tenosynovitis, pain in the bicipital groove is reproduced by resisted supination of the forearm with the elbow 90° flexed (Yergeson sign or supination sign; Figure 2-13) and by the more sensitive Speed test, in which there is pain on resisted flexion of the shoulder with the elbow extended and the forearm supinated.

In the O’Brien active compression test, with the patient standing, elbow extended, and the shoulder forward flexed 90°, adducted 15°, and internally rotated, so that the thumb points downward, the examiner applies downward pressure on the proximal forearm against the patient’s resistance (Figure 2-14). The shoulder is then externally rotated, and the forearm is supinated, after which the maneuver is repeated. The test is positive if pain is elicited with the first maneuver but not with forearm supination. The thumb-down position (internal rotation) compresses the biceps–glenoid–labrum anchor, causing pain or a click deep in the shoulder if a SLAP lesion is present. In traumatic AC joint lesions, the O’Brien test may also produce more superficial pain on top of the shoulder.

Kim et al. (2001) described the biceps load II test to assess for the presence of a SLAP lesion. In this test, the patient lies supine with the arm abducted 120°, the elbow flexed to 90°, and the forearm supinated. The patient then flexes the elbow against the resistance of the examiner. Pain elicited by this maneuver constitutes a positive test.

The crank test is also used to detect a SLAP lesion. In this test the arm is abducted 160° with the elbow flexed 90°. The examiner then applies a compressive load across the joint while performing rotation of the shoulder. Pain, usually with external rotation of the shoulder, constitutes a positive test (Figure 2-15).

Tests for Glenohumeral Instability

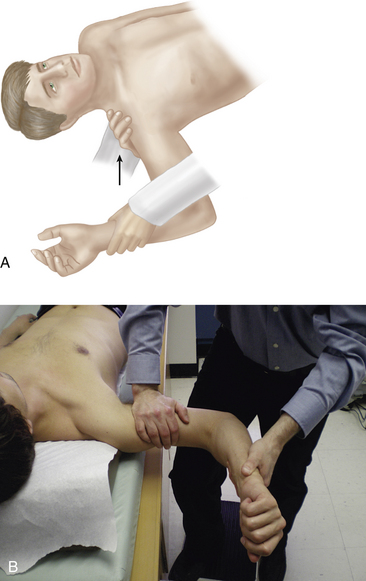

With the patient supine, the shoulder is 90° abducted and 90° externally rotated; the examiner then applies forward pressure to the posterior aspect of the humeral head (Figure 2-16A). In the presence of GH instability and recurrent anterior subluxation, the patient suddenly becomes apprehensive and complains of pain in the shoulder (positive anterior apprehension test). The relocation test or containment sign (Figure 2-16B) is then performed by applying posterior pressure on the anterior aspect of the humeral head, to push the subluxed humeral head back in the glenoid fossa. Patients with GH instability and secondary impingement experience marked pain relief (positive relocation test). The examiner may then be able to externally rotate and extend the shoulder several degrees further while maintaining the posteriorly directed force on the humeral head. On release of the pressure on the humerus at this point, the patient complains of sudden pain (positive anterior release sign). The sign is more sensitive than the apprehension-relocation test in detecting occult GH instability.

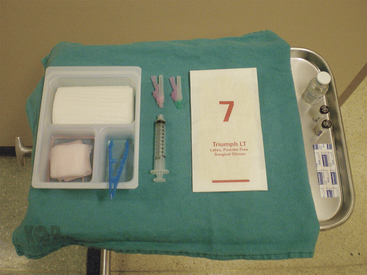

ASPIRATIONS AND INJECTIONS

Aspirations and injections are done about the shoulder for a number of indications. These include aspiration of a joint for synovial fluid analysis to aid in the diagnosis of inflammatory or septic arthritis. Injections of local anesthetic and antiinflammatory medications can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Injection of a specific site, if accompanied by symptomatic relief, can help confirm the diagnosis and aid further treatment. When performing these injections, sterile technique should always be adhered to. An example of the required equipment is shown in Figure 2-17.

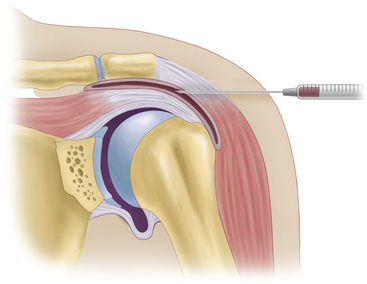

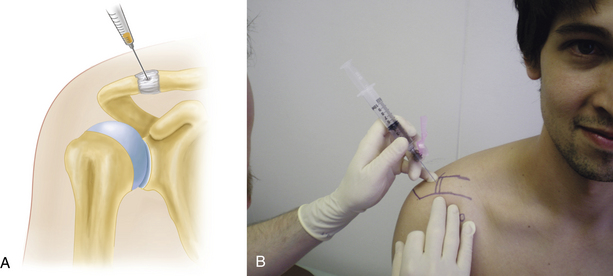

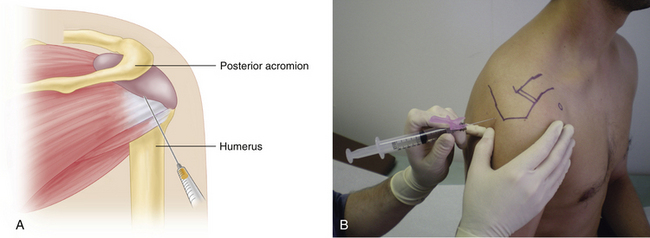

For subacromial bursa and rotator cuff tendinitis, with the patient sitting and the shoulder slightly externally rotated, the needle is inserted about 1 cm below the posterior border of the acromion and directed medially, anteriorly, and slightly superiorly toward the tip of the coracoid process to a depth of 2 to 3 cm into the subacromial bursa (posterior subacromial approach, Figure 2-18). A fluid-distended subacromial bursa can be aspirated and injected via a lateral approach (Figure 2-19).

FIGURE 2-18 INJECTION OF SUBACROMIAL BURSA AND ROTATOR CUFF TENDONS (POSTERIOR SUBACROMIAL APPROACH).

The GH joint is injected using a posterior approach. The entry point is two fingers’ breadth medial and inferior to the palpated posterolateral border of the acromion. The needle is directed anteromedial toward the coracoid process (Figure 2-20).

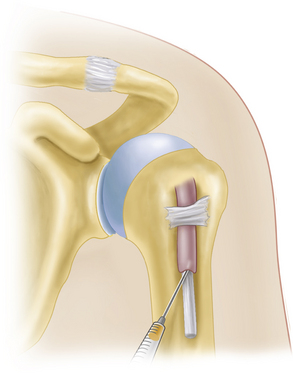

For injection of the bicipital tendon sheath, the patient is sitting or supine, and the tendon is palpated in the bicipital groove while the shoulder is externally rotated. The point of maximum tenderness is marked, and the needle is inserted at an angle of 30° to 45° into the sheath. It is then directed superiorly along the tendon for about 2 cm before the sheath is aspirated and injected (Figure 2-21). Care is taken to avoid intratendinous steroid injection, which can lead to tendon rupture.

The AC and SC joints are injected with the patient sitting or standing with the arm at the side. The AC or SC joint is palpated, and the needle is inserted via a superior and anterior approach into the joint and directed inferiorly to a depth of about 0.5 cm. Care is taken not to inject directly into the intraarticular disk, because this can damage the disk and cause secondary osteoarthritis (Figure 2-22).

Almekinders L.C. Impingement syndrome. Clin. Sports Med.. 2001;20:491-504.

Barth J.F., Burkhart S.S., De Beer J.F. The bear-hug test: A new and sensitive test for diagnosing a subscapularis tear. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1076-1084.

Debski R.E., Parsons I.M.I.V., Woo S.L.-Y., Fu F.H. Effect of capsular injury on acromioclavicular joint mechanics. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2001;83:1344-1351.

Doukas W.C., Speer K.P. Anatomy, pathophysiology, and biomechanics of shoulder instability. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 2001;32:381-391.

Fam A.G. Regional problems: The upper limbs in adults. In: Maddison P.J., Isenberg D.A., Woo P., Glass D.N., editors. Oxford Textbook of Rheumatology. second ed. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications; 1998:135-149.

Farber A.J., Castillo R., Clough M. Clinical assessment of three common tests for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 2006;88(A):1467-1474.

Gerber C., Krushell R.J. Isolated rupture of the tendon of the subscapularis muscle. Clinical features in 16 cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. – British. 1991;73(3):389-394.

Gerber C., Hersche O., Farron A. Isolated rupture of the subscapularis tendon. J. Bone Joint Surg. – American. 1996;78(7):1015-1023.

Hannafin J.A., Chiaia T.A. Adhesive capsulitis: A treatment approach. Clin. Orthop.. 2000;372:95-109.

Hertel R., Ballmer F.T., Lombert S.M., Gerber C. Lag signs in the diagnosis of rotator cuff rupture. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg.. 1996;5(4):307-313.

Kim S.H., Ha K.I., Ahn J.H., et al. Biceps load test II: A clinical test for SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(2):160-164.

Lui S.H., Henry M.H., Nuccion S.L. A prospective evaluation of a new physical examination in predicting glenoid labral tears. Am. J. Sports Med.. 1996;24(6):721-725.

Magee D.J. The shoulder. In: Magee D.J., editor. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. first ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1987:62-91.

Neer C.S.II. Impingement lesions. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res.. 1983;173:70-77.

Neer C.S.II, Welsh R.P. The shoulder in sports. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 1977;8(3):583-591.

Neviaser R.J. Painful conditions affecting the shoulder. Clin. Orthop. 1983;173:63-69.

Parentis M.A., Glousman R.E., Mohr K.S. An evaluation for the provocative tests for the superior labral anterior posterior lesions. Am. J. Sports Med.. 2006;34:265-268.

Park H.B., Yokota A., Gill H.S. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 2005;87(A):1446-1455.

Paulson M.M., Watnik N.F., Dines D.M. Coracoid impingement syndrome, rotator interval reconstruction and biceps tenodesis in the overhead athlete. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 2001;32:485-493.

Rothman R.H., Marvel J.P.Jr., Heppenstall R.B. Anatomic considerations in the glenohumeral joint. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1975;6:341-352.

Sarrafin S. Gross and functional anatomy of the shoulder. Clin. Orthop.. 1983;173:11-19.

Shaffer B., Tibone J.E., Kerlan R.K. Frozen shoulder: A long-term follow-up. J. Bone Joint. Surg. Am. 1992;74:738-746.

Tallia A.F., Cardone D.A. Diagnostic and therapeutic injection of the shoulder region. Am. Fam. Physician. 2003;67:1271-1278.

Tennet T.D., Beach W.R., Meyers J.F. A review of the special tests associated with shoulder examination. Part I: The rotator cuff tests. Am. J. Sports Med. 2003;31:154-160.

Tennet T.D., Beach W.R., Meyers J.F. A review of the special tests associated with shoulder examination. Part II: Laxity, instability, and superior labral anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions. Am. J. Sports Med. 2003;31:301-307.

Williams P.L., Warwick R., Dyson M., Bannister L.H. Joints of the upper limb. In Gray’s Anatomy, thirty seventh ed., Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1989:499-516.

Yergason R.M. Supination sign. J. Bone Joint Surg. – American. 1931;13(1):160.