Chapter 23 The seriously ill patient

tips and traps

It is the purpose of every emergency department to assess, resuscitate, diagnose and treat, both definitively and symptomatically, the patients who walk or are wheeled through the door.

There must be triage (sorting) and re-triage, especially if the department is busy. See Chapter 45, ‘Advanced nursing roles’.

Although it goes against human nature, ensure the difficulties are documented and submitted to the quality, risk system of your hospital. The system will respond, especially if serious or repeated problems are listed objectively. Emails to key people next working day also speed up action if critical issues are encountered.

WARNING—RED LIGHTS—BEWARE

For all of us there are red warning lights that alert us to potential pitfalls:

DECISION-MAKING TIPS

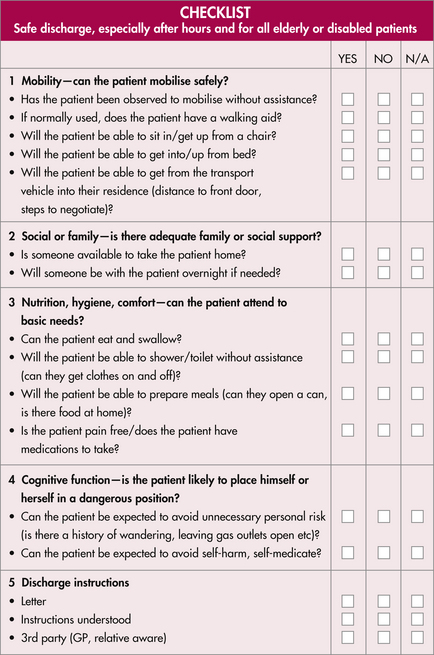

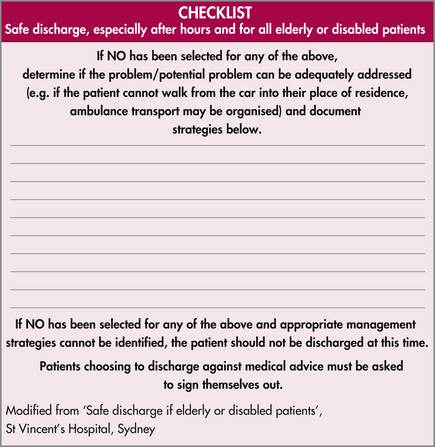

An important question is: ‘Does the patient need admission to hospital?’ This is better approached from the other perspective: ‘Is it safe or appropriate to send the patient home?’ If the answer is to be ‘yes’, refer to the discharge checklist in Box 23.1.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT ‘LAWS’

Law 2: Call for help early!

The team approach for complicated emergencies, such as trauma and cardiac arrest, should be activated early, i.e. even before they ‘crash’. Early involvement of intensive specialists, those responsible for definitive care, is imperative. Never be reticent to ask for more help—a ‘routine’ case of acute pulmonary oedema is enough work for two doctors in the initial resuscitation phase. Always aim for the hypothetical optimum care scenario, i.e. pretend that the patient is a loved relative.

If the patient is critical and unstable, call the arrest team or similar response team (e.g. MET) before it happens. The patient is much more likely to do better if you prevent the crash. See Table 23.1.

| Call for help for any patient who meets the following criteria | |

|---|---|

| CHANGE IN | PHYSIOLOGY |

| AIRWAY | |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Score

Based on criteria set out in Parr MJ, Hadfield JH, Flabouris A et al. The medical emergency team: a twelve month analysis for activation immediate outcome and not-for-resuscitation orders. Resuscitation 2001; 50:39–44

Law 3: Be flexible

Many sick patients defy any discrete label or have a diagnosis backed up by clearly abnormal tests. Follow your clinical impression, keep looking and be prepared to be surprised and change your management direction. If in doubt, observe.

Do not feed the lawyers

| EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT 10 COMMANDMENTS | |

|---|---|

| 1 | |