Chapter 9 The Second Year

Age 12-18 Months

Physical Development

Most children begin to walk independently near their 1st birthday; some do not walk until 15 mo of age. Early walking is not associated with advanced development in other domains. Infants initially toddle with a wide-based gait, with the knees bent and the arms flexed at the elbow; the entire torso rotates with each stride; the toes may point in or out, and the feet strike the floor flat. The appearance is that of genu varus (bowleg). Subsequent refinement leads to greater steadiness and energy efficiency. After several months of practice, the center of gravity shifts back and the torso stays more stable, while the knees extend and the arms swing at the sides for balance. The feet are held in better alignment, and the child is able to stop, pivot, and stoop without toppling over (Chapters 664 and 665).

Cognitive Development

Exploration of the environment increases in parallel with improved dexterity (reaching, grasping, releasing) and mobility. Learning follows the precepts of Piaget’s sensory-motor stage (Chapter 6). Toddlers manipulate objects in novel ways to create interesting effects, such as stacking blocks or putting things into a computer disk drive. Playthings are also more likely to be used for their intended purposes (combs for hair, cups for drinking). Imitation of parents and older children is an important mode of learning. Make-believe (symbolic) play centers on the child’s own body (pretending to drink from an empty cup) (Table 9-1; also see Table 8-1).

Table 9-1 EMERGING PATTERNS OF BEHAVIOR FROM 1 TO 5 YR OF AGE*

| 15 MO | |

| Motor: | Walks alone; crawls up stairs |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of 3 cubes; makes a line with crayon; inserts raisin in bottle |

| Language: | Jargon; follows simple commands; may name a familiar object (e.g., ball); responds to his/her name |

| Social: | Indicates some desires or needs by pointing; hugs parents |

| 18 MO | |

| Motor: | Runs stiffly; sits on small chair; walks up stairs with one hand held; explores drawers and wastebaskets |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of 4 cubes; imitates scribbling; imitates vertical stroke; dumps raisin from bottle |

| Language: | 10 words (average); names pictures; identifies one or more parts of body |

| Social: | Feeds self; seeks help when in trouble; may complain when wet or soiled; kisses parent with pucker |

| 24 MO | |

| Motor: | Runs well, walks up and down stairs, one step at a time; opens doors; climbs on furniture; jumps |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of 7 cubes (6 at 21 mo); scribbles in circular pattern; imitates horizontal stroke; folds paper once imitatively |

| Language: | Puts 3 words together (subject, verb, object) |

| Social: | Handles spoon well; often tells about immediate experiences; helps to undress; listens to stories when shown pictures |

| 30 MO | |

| Motor: | Goes up stairs alternating feet |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of 9 cubes; makes vertical and horizontal strokes, but generally will not join them to make cross; imitates circular stroke, forming closed figure |

| Language: | Refers to self by pronoun “I”; knows full name |

| Social: | Helps put things away; pretends in play |

| 36 MO | |

| Motor: | Rides tricycle; stands momentarily on one foot |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of 10 cubes; imitates construction of “bridge” of 3 cubes; copies circle; imitates cross |

| Language: | Knows age and sex; counts 3 objects correctly; repeats 3 numbers or a sentence of 6 syllables; most of speech intelligible to strangers |

| Social: | Plays simple games (in “parallel” with other children); helps in dressing (unbuttons clothing and puts on shoes); washes hands |

| 48 MO | |

| Motor: | Hops on one foot; throws ball overhand; uses scissors to cut out pictures; climbs well |

| Adaptive: | Copies bridge from model; imitates construction of “gate” of 5 cubes; copies cross and square; draws man with 2 to 4 parts besides head; identifies longer of 2 lines |

| Language: | Counts 4 pennies accurately; tells story |

| Social: | Plays with several children, with beginning of social interaction and role-playing; goes to toilet alone |

| 60 MO | |

| Motor: | Skips |

| Adaptive: | Draws triangle from copy; names heavier of 2 weights |

| Language: | Names 4 colors; repeats sentence of 10 syllables; counts 10 pennies correctly |

| Social: | Dresses and undresses; asks questions about meaning of words; engages in domestic role-playing |

* Data derived from those of Gesell (as revised by Knobloch), Shirley, Provence, Wolf, Bailey, and others. After 5 yr, the Stanford-Binet, Wechsler-Bellevue, and other scales offer the most precise estimates of developmental level. To have their greatest value, they should be administered only by an experienced and qualified person.

Emotional Development

Infants who are approaching the developmental milestone of taking their first steps may be irritable. Once they start walking, their predominant mood changes markedly. Toddlers are described as “intoxicated” or “giddy” with their new ability and with the power to control the distance between themselves and their parents. Exploring toddlers orbit around their parents, moving away and then returning for a reassuring touch before moving away again. A securely attached child will use the parent as a secure base from which to explore independently. Proud of her or his accomplishments, the child illustrates Erikson’s stage of autonomy and separation (Chapter 6). The toddler who is overly controlled and discouraged from active exploration will feel doubt, shame, anger, and insecurity. All children will experience tantrums, reflecting their inability to delay gratification, suppress or displace anger, or verbally communicate their emotional states. The quality of the maternal-child relationship may moderate negative effects of child care arrangements when parents work.

Linguistic Development

Receptive language precedes expressive language. By the time infants speak their first words around 12 mo of age, they already respond appropriately to several simple statements, such as “no,” “bye-bye,” and “give me.” By 15 mo, the average child points to major body parts and uses 4-6 words spontaneously and correctly. Toddlers also enjoy polysyllabic jargoning (see Tables 8-1 and 9-1), but do not seem upset that no one understands. Most communication of wants and ideas continues to be nonverbal.

Age 18-24 Months

Physical Development

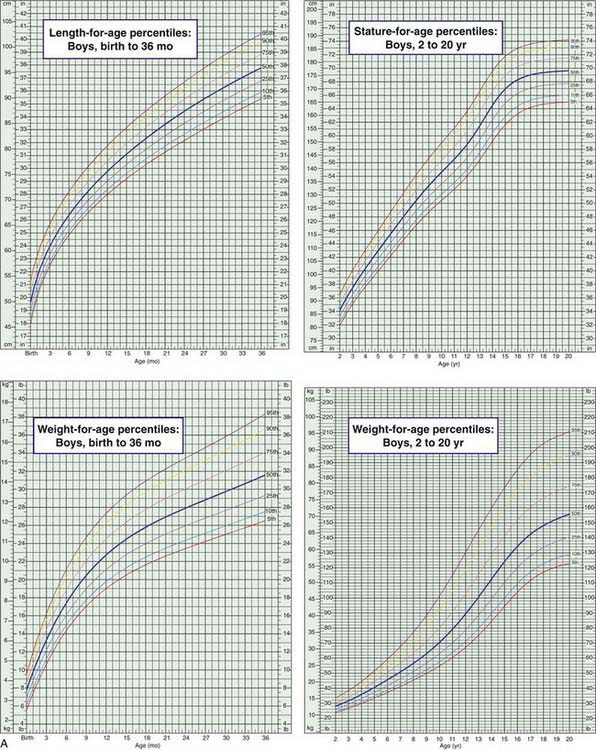

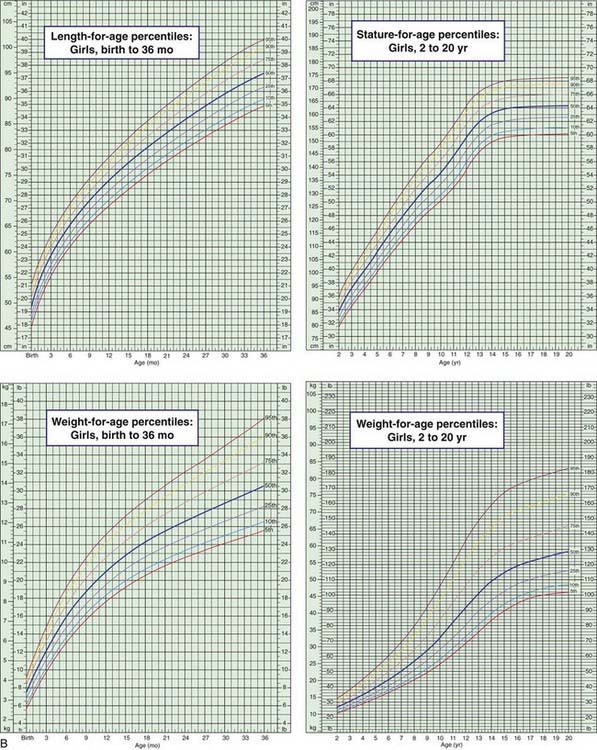

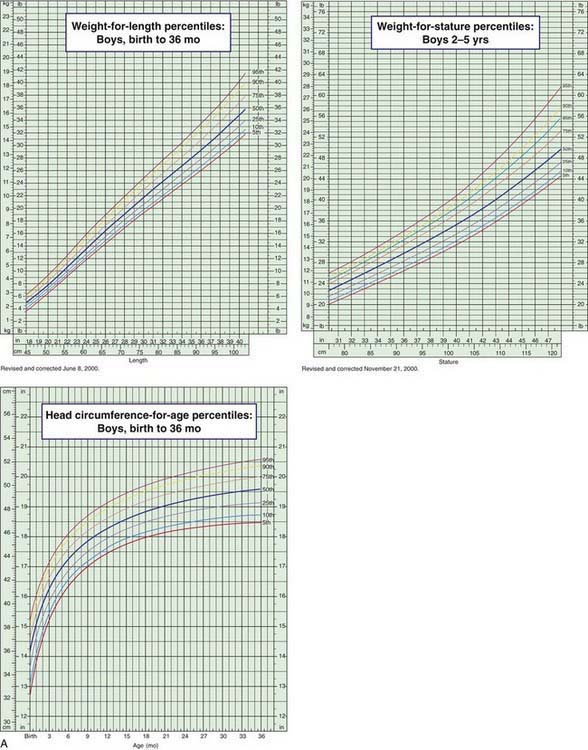

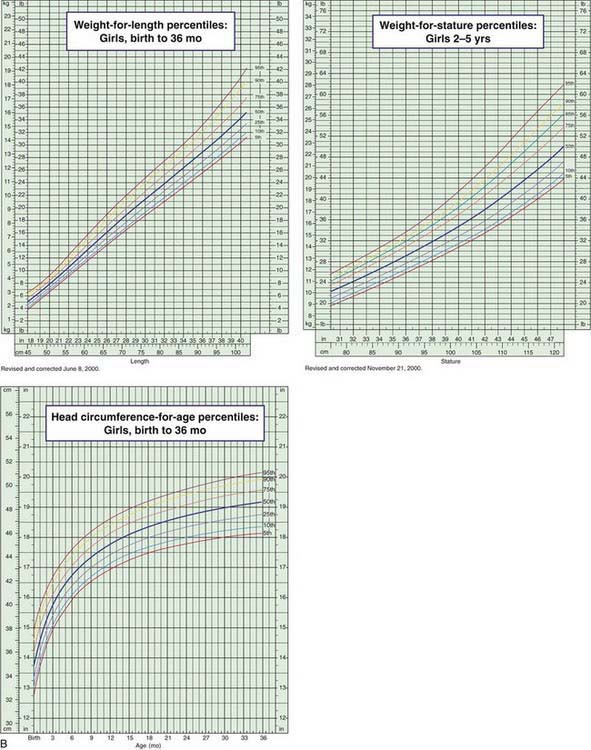

Motor development is incremental at this age, with improvements in balance and agility and the emergence of running and stair climbing. Height and weight increase at a steady rate during this year, with a gain of 5 in and 5 lb. By 24 mo, children are about  of their ultimate adult height. Head growth slows slightly. Ninety percent of adult head circumference is achieved by age 2 yr, with just an additional 5 cm gain over the next few years (Figs. 9-1 and 9-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at

of their ultimate adult height. Head growth slows slightly. Ninety percent of adult head circumference is achieved by age 2 yr, with just an additional 5 cm gain over the next few years (Figs. 9-1 and 9-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at ![]() www.expertconsult.com; see also Table 13-1).

www.expertconsult.com; see also Table 13-1).

(Official 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] growth charts, created by the National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS; see Chapter 13]. Infant length was measured lying; older children’s stature was measured standing. Additional information and technical reports available at www.cdc.gov/nchs.)

Figure 9-2 Head circumference and length/stature by weight for boys (A) and girls (B).

(Official 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] growth charts, created by the National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS; see Chapter 13]. Additional information and technical reports are available at www.cdc.gov/nchs.)

Cognitive Development

At approximately 18 mo of age, several cognitive changes come together to mark the conclusion of the sensory-motor period. These can be observed during self-initiated play. Object permanence is firmly established; toddlers anticipate where an object will end up, even though the object was not visible while it was being moved. Cause and effect are better understood, and toddlers demonstrate flexibility in problem solving (e.g., using a stick to obtain a toy that is out of reach, figuring out how to wind a mechanical toy). Symbolic transformations in play are no longer tied to the toddler’s own body, so that a doll can be “fed” from an empty plate. Like the reorganization that occurs at 9 mo, the cognitive changes at 18 mo correlate with important changes in the emotional and linguistic domains (see Table 9-1).

Implications for Parents and Pediatricians

In the office setting, certain procedures may lessen the child’s stranger anxiety. Avoid direct eye contact initially. Perform as much of the examination as feasible with the child on the parent’s lap. Pediatricians can help parents understand the resurgence of problems with separation and the appearance of a treasured blanket or teddy bear as a developmental phenomenon. Parents must understand the importance of exploration. Rather than limiting movement, parents should place toddlers in safe environments or substitute 1 activity for another. Methods of discipline, including corporal punishment, should be discussed; effective alternatives will usually be appreciated. Helping parents to understand and adapt to their children’s different temperamental styles can constitute an important intervention (see Table 6-1). Developing daily routines is helpful to all children at this age. Rigidity in those routines reflects a need for mastery over a changing environment.

Almli CR, Rivkin MJ, McKinstry RC. Brain Development Cooperative Group. The NIH MRI study of normal brain development (Objective-2): newborns, infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Neuroimage. 2007;35:308-325.

Bates E, Dick F. Language, gesture, and the developing brain. Dev Psychobiol. 2002;40:293-310.

Christakis DA, Gilkerson J, Richards JA, et al. Audible television and decreased adult words, infant vocalizations, and conversational turns: a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:554-558.

Dixon SD, Hennessy MJ. One year: one giant step forward. In: Dixon SD, Stein MT, editors. Encounters with children: pediatric behavior and development. St Louis: Mosby; 2000:247-276.

Fraiberg S. The magic years. New York: Scribner; 1959.

Knickmeyer RC, Gouttard S, Kang C, et al. A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. J Neurosci. 2008;28(47):12176-12182.

Lieberman A. The emotional life of the toddler. New York: Free Press; 1993.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. Families matter—even for kids in child care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24:58-62.