12e |

The Safety and Quality of Health Care |

Safety and quality are two of the central dimensions of health care. In recent years it has become easier to measure safety and quality, and it is increasingly clear that performance in both dimensions could be much better. The public is—with good justification—demanding measurement and accountability, and payment for services will increasingly be based on performance in these areas. Thus, physicians must learn about these two domains, how they can be improved, and the relative strengths and limitations of the current ability to measure them.

Safety and quality are closely related but do not completely overlap. The Institute of Medicine has suggested in a seminal series of reports that safety is the first part of quality and that the health care system must first and foremost guarantee that it will deliver safe care, although quality is also pivotal. In the end, it is likely that more net clinical benefit will be derived from improving quality than from improving safety, though both are important and safety is in many ways more tangible to the public. The first section of this chapter will address issues relating to the safety of care and the second will cover quality of care.

SAFETY IN HEALTH CARE

Safety Theory and Systems Theory Safety theory clearly points out that individuals make errors all the time. Think of driving home from the hospital: you intend to stop and pick up a quart of milk on the way home but find yourself entering your driveway without realizing how you got there. Everybody uses low-level, semiautomatic behavior for many activities in daily life; this kind of error is called a slip. Slips occur often during care delivery—e.g., when people intend to write an order but forget because they have to complete another action first. Mistakes, by contrast, are errors of a higher level; they occur in new or nonstereotypic situations in which conscious decisions are being made. An example would be dosing of a medication with which a physician is not familiar. The strategies used to prevent slips and mistakes are often different.

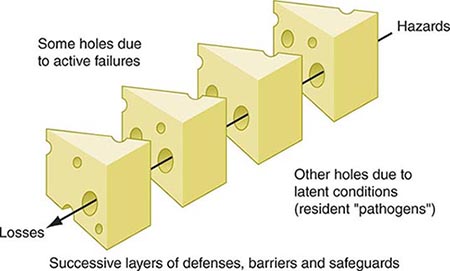

Systems theory suggests that most accidents occur as the result of a series of small failures that happen to line up in an individual instance so that an accident can occur (Fig. 12e-1). It also suggests that most individuals in an industry such as health care are trying to do the right thing (e.g., deliver safe care) and that most accidents thus can be seen as resulting from defects in systems. Systems should be designed both to make errors less likely and to identify those that do inevitably occur.

FIGURE 12e-1 “Swiss cheese” diagram. Reason argues that most accidents occur when a series of “latent failures” are present in a system and happen to line up in a given instance, resulting in an accident. Examples of latent failures in the case of a fall might be that the unit is unusually busy and the floor happens to be wet. (Adapted from J Reason: BMJ 320:768, 2000; with permission.)

Factors that Increase the Likelihood of Errors Many factors ubiquitous in health care systems can increase the likelihood of errors, including fatigue, stress, interruptions, complexity, and transitions. The effects of fatigue in other industries are clear, but its effects in health care have been more controversial until recently. For example, the accident rate among truck drivers increases dramatically if they work over a certain number of hours in a week, especially with prolonged shifts. A recent study of house officers in the intensive care unit demonstrated that they were about one-third more likely to make errors when they were on a 24-h shift than when they were on a schedule that allowed them to sleep 8 h the previous night. The American College of Graduate Medical Education has moved to address this issue by putting in place the 80-h workweek. Although this stipulation is a step forward, it does not address the most important cause of fatigue-related errors: extended-duty shifts. High levels of stress and heavy workloads also can increase error rates. Thus, in extremely high-pressure situations, such as cardiac arrests, errors are more likely to occur. Strategies such as using protocols in these settings can be helpful, as can simple recognition that the situation is stressful.

Interruptions also increase the likelihood of error and occur frequently in health care delivery. It is common to forget to complete an action when one is interrupted partway through it by a page, for example. Approaches that may be helpful in this area include minimizing interruptions and setting up tools that help define the urgency of an interruption.

Complexity represents a key issue that contributes to errors. Providers are confronted by streams of data (e.g., laboratory tests and vital signs), many of which provide little useful information but some of which are important and require action or suggest a specific diagnosis. Tools that emphasize specific abnormalities or combinations of abnormalities may be helpful in this area.

Transitions between providers and settings are also common in health care, especially with the advent of the 80-h workweek, and generally represent points of vulnerability. Tools that provide structure in exchanging information—for example, when transferring care between providers—may be helpful.

The Frequency of Adverse Events in Health Care Most large studies focusing on the frequency and consequences of adverse events have been performed in the inpatient setting; some data are available for nursing homes, but much less information is available about the outpatient setting. The Harvard Medical Practice Study, one of the largest studies to address this issue, was performed with hospitalized patients in New York. The primary outcome was the adverse event: an injury caused by medical management rather than by the patient’s underlying disease. In this study, an event either resulted in death or disability at discharge or prolonged the length of hospital stay by at least 2 days. Key findings were that the adverse event rate was 3.7% and that 58% of the adverse events were considered preventable. Although New York is not representative of the United States as a whole, the study was replicated later in Colorado and Utah, where the rates were essentially similar. Since then, other studies using analogous methodologies have been performed in various developed nations, and the rates of adverse events in these countries appear to be ~10%. Rates of safety issues appear to be even higher in developing and transitional countries; thus, this is clearly an issue of global proportions. The World Health Organization has focused on this area, forming the World Alliance for Patient Safety.

In the Harvard Medical Practice Study, adverse drug events (ADEs) were most common, accounting for 19% of all adverse events, and were followed in frequency by wound infections (14%) and technical complications (13%). Almost half of adverse events were associated with a surgical procedure. Among nonoperative events, 37% were ADEs, 15% were diagnostic mishaps, 14% were therapeutic mishaps, 13% were procedure-related mishaps, and 5% were falls.

ADEs have been studied more than any other error category. Studies focusing specifically on ADEs have found that they appear to be much more common than was suggested by the Harvard Medical Practice Study, although most other studies use more inclusive criteria. Detection approaches in the research setting include chart review and the use of a computerized ADE monitor, a tool that explores the database and identifies signals that suggest an ADE may have occurred. Studies that use multiple approaches find more ADEs than does any individual approach, and this discrepancy suggests that the true underlying rate in the population is higher than would be identified by a single approach. About 6–10% of patients admitted to U.S. hospitals experience an ADE.

Injuries caused by drugs are also common in the outpatient setting. One study found a rate of 21 ADEs per every 100 patients per year when patients were called to assess whether they had had a problem with one of their medications. The severity level was lower than in the inpatient setting, but approximately one-third of these ADEs were preventable.

The period immediately after a patient is discharged from the hospital appears to be very risky. A recent study of patients hospitalized on a medical service found an adverse event rate of 19%; about one-third of those events were preventable, and another one-third were ameliorable (i.e., they could have been made less severe). ADEs were the single leading error category.

Prevention Strategies Most work on strategies to prevent adverse events has targeted specific types of events in the inpatient setting, with nosocomial infections and ADEs having received the most attention. Nosocomial infection rates have been reduced greatly in intensive care settings, especially through the use of checklists. For ADEs, several strategies have been found to reduce the medication error rate, although it has been harder to demonstrate that they reduce the ADE rate overall, and no studies with adequate power to show a clinically meaningful reduction have been published.

Implementation of checklists to ensure that specific actions are carried out has had a major impact on rates of catheter-associated bloodstream infection and ventilator-associated pneumonia, two of the most serious complications occurring in intensive care units. The checklist concept is based on the premise that several specific actions can reduce the frequency of these issues; when these actions are all taken for every patient, the result has been an extreme reduction in the frequency of the associated complication. These practices have been disseminated across wide areas, in particular in the state of Michigan.

Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) linked with clinical decision support reduces the rate of serious medication errors, defined as those that harm someone or have the potential to do so. In one study, CPOE, even with limited decision support, decreased the serious medication error rate by 55%. CPOE can prevent medication errors by suggesting a default dose, ensuring that all orders are complete (e.g., that they include dose, route, and frequency), and checking orders for allergies, drug–drug interactions, and drug–laboratory issues. In addition, clinical decision support can suggest the right dose for a patient, tailoring it to level of renal function and age. In one study, patients with renal insufficiency received the appropriate dose only one-third of the time without decision support, whereas that fraction increased to approximately two-thirds with decision support; moreover, with such support, patients with renal insufficiency were discharged from the hospital half a day earlier. As of 2009, only ~15% of U.S. hospitals had implemented CPOE, but many plan to do so and will receive major financial incentives for achieving this goal.

Another technology that can improve medication safety is bar coding linked with an electronic medication administration record. Bar coding can help ensure that the right patient gets the right medication at the right time. Electronic medication administration records can make it much easier to determine what medications a patient has received. Studies to assess the impact of bar coding on medication safety are under way, and the early results are promising. Another technology to improve medication safety is “smart pumps.” These pumps can be set according to which medication is being given and at what dose; the health care professional will receive a warning if too high a dose is about to be administered.

The National Safety Picture Several organizations, including the National Quality Forum and the Joint Commission, have made recommendations for improving safety. In particular, the National Quality Forum has released recommendations to U.S. hospitals about what practices will most improve the safety of care, and all hospitals are expected to implement these recommendations. Many of these practices arise frequently in routine care. One example is “readback,” the practice of recording all verbal orders and immediately reading them back to the physician to verify the accuracy of what was heard. Another is the consistent use of standard abbreviations and dose designations; some abbreviations and dose designations are particularly prone to error (e.g., 7U may be read as 70).

Measurement of Safety Measuring the safety of care is difficult and expensive, since adverse events are, fortunately, rare. Most hospitals rely on spontaneous reporting to identify errors and adverse events, but the sensitivity of this approach is very low, with only ~1 in 20 ADEs reported. Promising research techniques involve searching the electronic record for signals suggesting that an adverse event has occurred. These methods are not yet in wide use but will probably be used routinely in the future. Claims data have been used to identify the frequency of adverse events; this approach works much better for surgical care than for medical care and requires additional validation. The net result is that, except for a few specific types of events (e.g., falls and nosocomial infections), hospitals have little idea about the true frequency of safety issues.

Nonetheless, all providers have the responsibility to report problems with safety as they are identified. All hospitals have spontaneous reporting systems, and, if providers report events as they occur, those events can serve as lessons for subsequent improvement.

Conclusions about Safety It is abundantly clear that the safety of health care can be improved substantially. As more areas are studied closely, more problems are identified. Much more is known about the epidemiology of safety in the inpatient setting than in outpatient settings. A number of effective strategies for improving inpatient safety have been identified and are increasingly being applied. Some effective strategies are also available for the outpatient setting. Transitions appear to be especially risky. The solutions to improving care often entails the consistent use of systematic techniques such as checklists and often involves leveraging of information technology. Nevertheless, solutions will also include many other domains, such human factors techniques, team training, and a culture of safety.

QUALITY IN HEALTH CARE

Assessment of quality of care has remained somewhat elusive, although the tools for this purpose have increasingly improved. Selection of health care and measurement of its quality are components of a complex process.

Quality Theory Donabedian has suggested that quality of care can be categorized by type of measurement into structure, process, and outcome. Structure refers to whether a particular characteristic is applicable in a particular setting—e.g., whether a hospital has a catheterization laboratory or whether a clinic uses an electronic health record. Process refers to the way care is delivered; examples of process measures are whether a Pap smear was performed at the recommended interval or whether an aspirin was given to a patient with a suspected myocardial infarction. Outcome refers to what actually happens—e.g., the mortality rate in myocardial infarction. It is important to note that good structure and process do not always result in a good outcome. For instance, a patient may present with a suspected myocardial infarction to an institution with a catheterization laboratory and receive recommended care, including aspirin, but still die because of the infarction.

Quality theory also suggests that overall quality will be improved more in the aggregate if the performance level of all providers is raised rather than if a few poor performers are identified and punished. This view suggests that systems changes are especially likely to be helpful in improving quality, since large numbers of providers may be affected simultaneously.

The theory of continuous quality improvement suggests that organizations should be evaluating the care they deliver on an ongoing basis and continually making small changes to improve their individual processes. This approach can be very powerful if embraced over time.

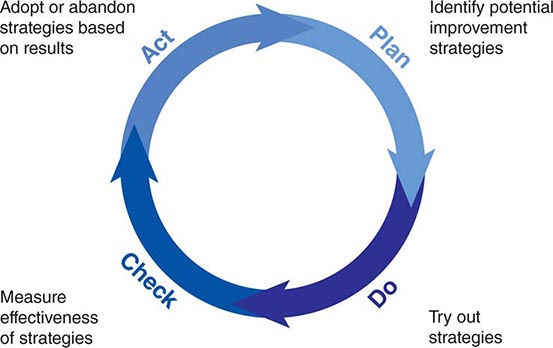

A number of specific tools have been developed to help improve process performance. One of the most important is the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle (Fig. 12e-2). This approach can be used for “rapid cycle” improvement of a process—e.g., the time that elapses between a diagnosis of pneumonia and administration of antibiotics to the patient. Specific statistical tools, such as control charts, are often used in conjunction to determine whether progress is being made. Because most medical care includes one or many processes, this tool is especially important for improvement.

FIGURE 12e-2 Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. This approach can be used to improve a specific process rapidly. First, planning is undertaken, and several potential improvement strategies are identified. Next, these strategies are evaluated in small “tests of change.” “Checking” entails measuring whether the strategies have appeared to make a difference, and “acting” refers to acting on the results.

Factors Relating to Quality Many factors can decrease the level of quality, including stress to providers, high or low levels of production pressure, and poor systems. Stress can have an adverse effect on quality because it can lead providers to omit important steps, as can a high level of production pressure. Low levels of production pressure sometimes can result in worse quality, as providers may be bored or have little experience with a specific problem. Poor systems can have a tremendous impact on quality, and even extremely dedicated providers typically cannot achieve high levels of performance if they are operating within a poor system.

Data about the Current State of Quality A study published by the RAND Corporation in 2006 provided the most complete picture of quality of care delivered in the United States to date. The results were sobering. The authors found that, across a wide range of quality parameters, patients in the United States received only 55% of recommended care overall; there was little variation by subtype, with scores of 54% for preventive care, 54% for acute care, and 56% for care of chronic conditions. The authors concluded that, in broad terms, the chances of getting high-quality care in the United States were little better than those of winning a coin flip.

Work from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care evaluating geographic variation in use and quality of care demonstrates that, despite large variations in utilization, there is no positive correlation between the two variables at the regional level. An array of data demonstrate, however, that providers with larger volumes for specific conditions, especially for surgical conditions, do have better outcomes.

Strategies for Improving Quality and Performance A number of specific strategies can be used to improve quality at the individual level, including rationing, education, feedback, incentives, and penalties. Rationing has been effective in some specific areas, such as persuading physicians to prescribe within a formulary, but it generally has been resisted. Education is effective in the short run and is necessary for changing opinions, but its effect decays fairly rapidly with time. Feedback on performance can be given at either the group or the individual level. Feedback is most effective if it is individualized and is given in close temporal proximity to the original events. Incentives can be effective, and many believe that they will prove to be a key to improving quality, especially if pay-for-performance with sufficient incentives is broadly implemented (see below). Penalties produce provider resentment and are rarely used in health care.

Another set of strategies for improving quality involves changing the systems of care. An example would be introducing reminders about which specific actions needed to be taken at a visit for a specific patient—a strategy that has been demonstrated to improve performance in certain situations, such as the delivery of preventive services. Another approach that has been effective is the development of “bundles” or groups of quality measures that can be implemented together with a high degree of fidelity. A number of hospitals have implemented a bundle for ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit that includes five measures (e.g., ensuring that the head of the bed is elevated). These hospitals have been able to improve performance substantially.

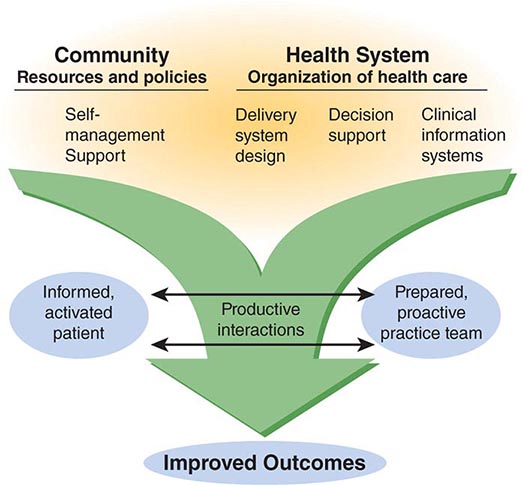

Perhaps the most pressing need is to improve the quality of care for chronic diseases. The Chronic Care Model has been developed by Wagner and colleagues (Fig. 12e-3); it suggests that a combination of strategies is necessary (including self-management support, changes in delivery system design, decision support, and information systems) and that these strategies must be delivered by a practice team composed of several providers, not just a physician.

FIGURE 12e-3 The Chronic Care Model, which focuses on improving care for chronic diseases, suggests that (1) delivery of high-quality care requires a range of strategies that must closely involve and engage the patient and (2) team care is essential. (From EH Wagner et al: Eff Clin Pract 1:2, 1998.)

Available evidence about the relative efficacy of strategies in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in outpatient diabetes care supports this general premise. It is especially notable that the outcome was the HbA1c level, as it has generally been much more difficult to improve outcome measures than process measures (such as whether HbA1c was measured). In this meta-analysis, a variety of strategies were effective, but the most effective ones were the use of team changes and the use of a case manager. When cost-effectiveness is considered in addition, it appears likely that an amalgam of strategies will be needed. However, the more expensive strategies, such as the use of case managers, probably will be implemented widely only if pay-for-performance takes hold.

National State of Quality Measurement In the inpatient setting, quality measurement is now being performed by a very large proportion of hospitals for several conditions, including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and surgical infection prevention; 20 measures are included in all. This is the result of the Hospital Quality Initiative, which represents a collaboration among many entities, including the Hospital Quality Alliance, the Joint Commission, the National Quality Forum, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The data are housed at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which publicly releases performance data on the measures on a website called Hospital Compare (www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalCompare.html). These data are reported voluntarily and are available for a very high proportion of the nation’s hospitals. Analyses demonstrate substantial regional variation in quality and important differences among hospitals. Analyses by the Joint Commission for similar indicators reveal that performance on measures by hospitals has improved over time and that, as might be hoped, lower performers have improved more than higher performers.

Public Reporting Overall, public reporting of quality data is becoming increasingly common. There are now commercial websites that have quality-related data for most regions of the United States, and these data can be accessed for a fee. Similarly, national data for hospitals are available. The evidence to date indicates that patients have not made much use of such data but that the data have had an important effect on provider and organization behavior. Instead, patients have relied on provider reputation to make choices, partly because little information was available until very recently and the information that was available was not necessarily presented in ways that were easy for patients to access. Many authorities think that, as more information about quality becomes available, it will become increasingly central to patients’ choices about where to access care.

Pay-for-Performance Currently, providers in the United States get paid exactly the same amount for a specific service, regardless of the quality of care delivered. The pay-for-performance theory suggests that, if providers are paid more for higher-quality care, they will invest in strategies that enable them to deliver that care. The current key issues in the pay-for-performance debate relate to (1) how effective it is, (2) what levels of incentives are needed, and (3) what perverse consequences are produced. The evidence on effectiveness is fairly limited, although a number of studies are ongoing. With respect to incentive levels, most quality-based performance incentives have accounted for merely 1–2% of total payment in the United States to date. In the United Kingdom, however, 40% of general practitioners’ salaries have been placed at risk according to performance across a wide array of parameters; this approach has been associated with substantial improvements in reported quality performance, although it is still unclear to what extent this change represents better performance versus better reporting. The potential for perverse consequences exists with any incentive scheme. One problem is that, if incentives are tied to outcomes, there may be a tendency to transfer the sickest patients to other providers and systems. Another concern is that providers will pay too much attention to quality measures with incentives and ignore the rest of the quality picture. The validity of these concerns remains to be determined. Nonetheless, it appears likely that, under health care reform, the use of various pay-for-performance schemes is likely to increase.

CONCLUSIONS

The safety and quality of care in the United States could be improved substantially. A number of available interventions have been shown to improve the safety of care and should be used more widely; others are undergoing evaluation or soon will be. Quality also could be dramatically better, and the science of quality improvement continues to mature. Implementation of pay-for-performance should make it much easier for organizations to justify investments in improving safety and quality parameters, including health information technology. However, many improvements will also require changing the structure of care—e.g., moving to a more team-oriented approach and ensuring that patients are more involved in their own care. Health care reform is likely to result in increased use of pay-for-performance. Measures of safety are still relatively immature and could be made much more robust; it would be particularly useful if organizations had measures they could use in routine operations to assess safety at a reasonable cost. Although the quality measures available are more robust than those for safety, they still cover a relatively small proportion of the entire domain of quality, and more measures need to be developed. The public and payers are demanding better information about safety and quality as well as better performance in these areas. The clear implication is that these domains will have to be addressed directly by providers.

13e |

Primary Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

The twentieth century witnessed the rise of an unprecedented global health divide. Industrialized or high-income countries experienced rapid improvement in standards of living, nutrition, health, and health care. Meanwhile, in low- and middle-income countries with much less favorable conditions, health and health care progressed much more slowly. The scale of this divide is reflected in the current extremes of life expectancy at birth, with Japan at the high end (83 years) and Sierra Leone at the low end (47 years). This nearly 40-year difference reflects the daunting range of health challenges faced by low- and middle-income countries. These nations must deal not only with a complex mixture of diseases (both infectious and chronic) and illness-promoting conditions but also, and more fundamentally, with the fragility of the foundations underlying good health (e.g., sufficient food, water, sanitation, and education) and of the systems necessary for universal access to good-quality health care. In the last decades of the twentieth century, the need to bridge this global health divide and establish health equity was increasingly recognized. The Declaration of Alma Ata in 1978 crystallized a vision of justice in health, regardless of income, gender, ethnicity, or education, and called for “health for all by the year 2000” through primary health care. While much progress has been made since the declaration, at the end of the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century, much remains to be done to achieve global health equity.

This chapter looks first at the nature of the health challenges in low- and middle-income countries that underlie the health divide. It then outlines the values and principles of a primary health care approach, with a focus on primary care services. Next, the chapter reviews the experience of low- and middle-income countries in addressing health challenges through primary care and a primary health care approach. Finally, the chapter identifies how current challenges and global context provide an agenda and opportunities for the renewal of primary health care and primary care.

PRIMARY CARE AND PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

The term primary care has been used in many different ways: to describe a level of care or the setting of the health system, a set of treatment and prevention activities carried out by specific personnel, a set of attributes for the way care is delivered, or an approach to organizing health systems that is synonymous with the term primary health care. In 1996, the U.S. Institute of Medicine encompassed many of these different usages, defining primary care as “the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.”1 We use this definition of primary care in this chapter. Primary care performs an essential function for health systems, providing the first point of contact when people seek health care, dealing with most problems, and referring patients onward to other services when necessary. As is increasingly evident in countries of all income levels, without strong primary care, health systems cannot function properly or address the health challenges of the communities they serve.

Primary care is only one part of a primary health care approach. The Declaration of Alma Ata, drafted in 1978 at the International Conference on Primary Health Care in Alma Ata (now Almaty in Kazakhstan), identified many features of primary care as being essential to achieving the goal of “health for all by the year 2000.” However, it also identified the need to work across different sectors, address the social and economic factors that determine health, mobilize the participation of communities in health systems, and ensure the use and development of technology that was appropriate in terms of setting and cost. The declaration drew from the experiences of low- and middle-income countries in trying to improve the health of their people following independence. Commonly, these countries had built hospital-based systems similar to those in high-income countries. This effort had resulted in the development of high-technology services in urban areas while leaving the bulk of the population without access to health care unless they traveled great distances to these urban facilities. Furthermore, much of the population lacked access to basic public health measures. Primary health care efforts aimed to move care closer to where people lived, to ensure their involvement in decisions about their own health care, and to address key aspects of the physical and social environment essential to health, such as water, sanitation, and education.

After the Declaration of Alma Ata, many countries implemented reforms of their health systems based on primary health care. Most progress involved strengthening of primary care services; unexpectedly, however, much of this progress was seen in high-income countries, most of which constructed systems that made primary care available at low or no cost to their entire populations and that delivered the bulk of services in primary care settings. This endeavor also saw the reinforcement of family medicine as a specialty to provide primary care services. Even in the United States (an obvious exception to this trend), it became clear that the populations of states with more primary care physicians and services were healthier than those with fewer such resources.

Progress was also made in many low- and middle-income countries. However, the target of “health for all by the year 2000” was missed by a large margin. The reasons were complex but partly entailed a general failure to implement all aspects of the primary health care approach, particularly work across sectors to address social and economic factors that affect health and provision of sufficient human and other resources to make possible the access to primary care attained in high-income countries. Furthermore, despite the consensus in Alma Ata in 1978, the global health community rapidly became fractured in its commitment to the far-reaching measures called for by the declaration. Economic recession tempered enthusiasm for primary health care, and momentum shifted to programs concentrating on a few priority measures such as immunization, oral rehydration, breast-feeding, and growth monitoring for child survival. Success with these initiatives supported the continued movement of health development efforts away from the comprehensive approach of primary health care and toward programs that targeted specific public health priorities. This approach was reinforced by the need to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic. By the 1990s, primary health care had fallen out of favor in many global-health policy circles, and low- and middle-income countries were being encouraged to reduce public sector spending on health and to focus on cost-effectiveness analysis to provide a package of health care measures thought to offer the greatest health benefits.

HEALTH CHALLENGES IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

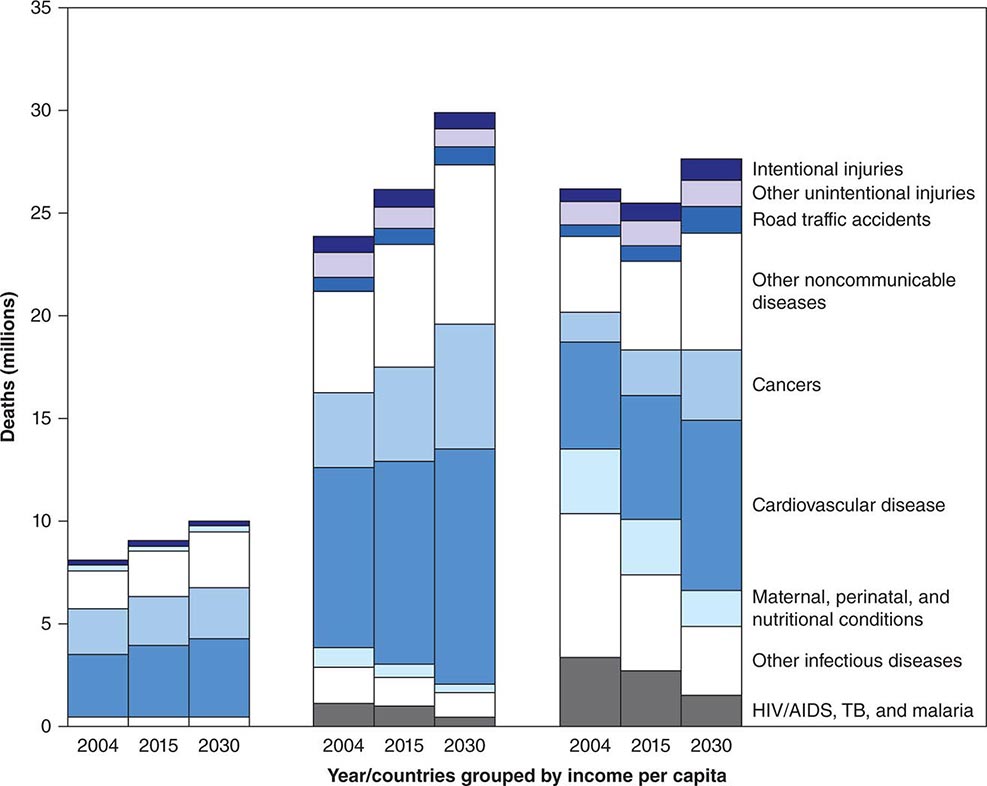

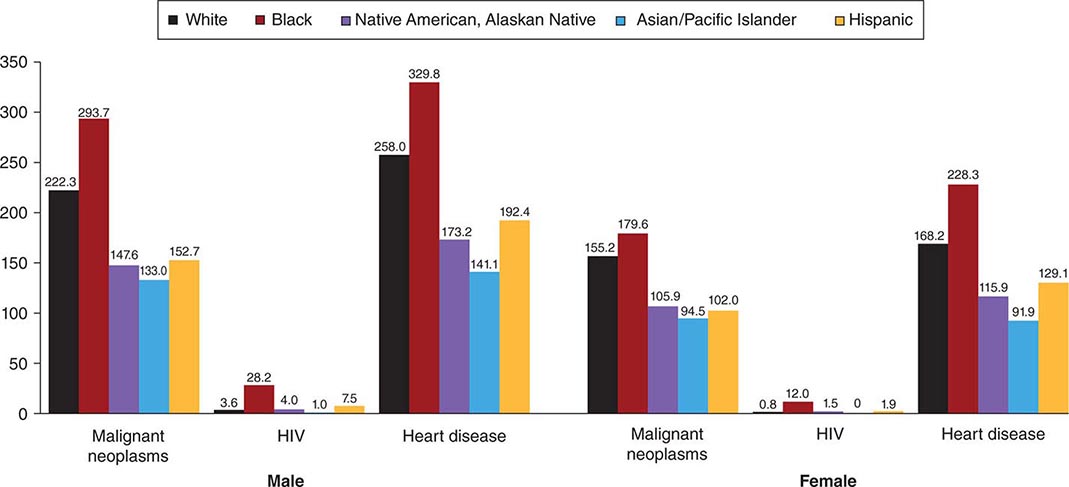

Low- and middle-income countries, defined by a per capita gross national income of <$12,476 (U.S.) per person per year, account for >80% of the world’s population. Average life expectancy in these countries lags far behind that in high-income countries: whereas the average life expectancy at birth in high-income countries is 74 years, it is only 68 years in middle-income countries and 58 years in low-income countries. This discrepancy has received growing attention over the past 40 years. Initially, the situation in poor countries was characterized primarily in terms of high fertility and high infant, child, and maternal mortality rates, with most deaths and illnesses attributable to infectious or tropical diseases among remote, largely rural populations. With growing adult (and especially elderly) populations and changing lifestyles linked to global forces of urbanization, a new set of health challenges characterized by chronic diseases, environmental overcrowding, and road traffic injuries has emerged rapidly (Fig. 13e-1). The majority of tobacco-related deaths globally now occur in low- and middle-income countries, and the risk of a child’s dying from a road traffic injury in Africa is more than twice that in Europe. Hence, low- and middle-income countries in the twenty-first century face a full spectrum of health challenges—infectious, chronic, and injury-related—at much higher incidences and prevalences than are documented in high-income countries and with many fewer resources to address these challenges.

FIGURE 13e-1 Projections of disease burden to 2030 for high-, middle-, and low-income countries (left, center, and right, respectively). TB, tuberculosis. (Source: World Health Organization: The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update, 2008.)

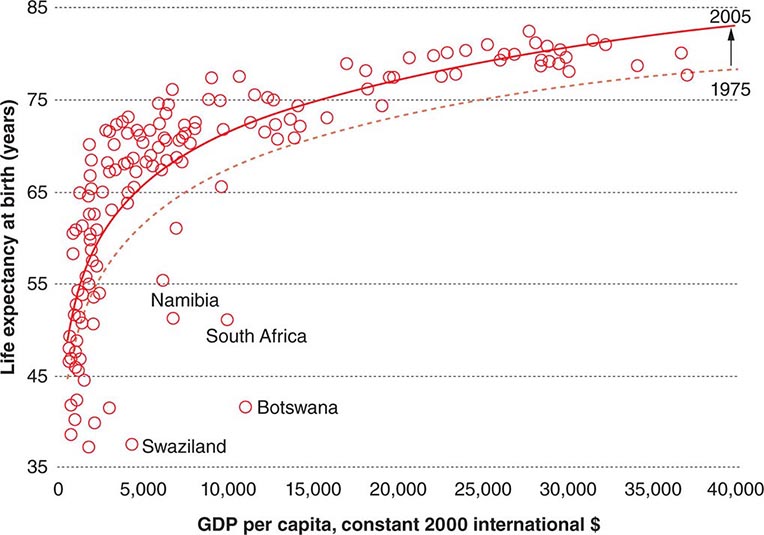

Addressing these challenges, however, does not mean simply waiting for economic growth. Analysis of the association between wealth and health across countries reveals that, for any given level of wealth, there is a substantial variation in life expectancy at birth that has persisted despite overall global progress in life expectancy during the past 30 years (Fig. 13e-2). Health status in low- and middle-income countries varies enormously. Nations such as Cuba and Costa Rica have life expectancies and childhood mortality rates similar to or even better than those in high-income countries; in contrast, countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the former Soviet bloc have experienced significant reverses in these health markers in the past 20 years.

FIGURE 13e-2 Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and life expectancy at birth in 169 countries, 1975 and 2005. Only outlying countries are named. (Source: World Health Organization: Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. World Health Report 2008.)

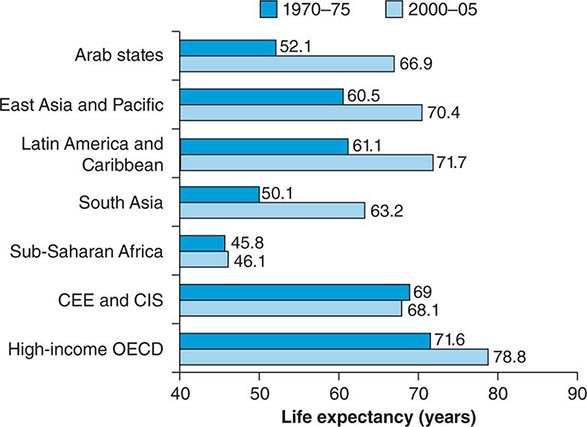

As Angus Deaton stated in the World Institute for Development Economics Research annual lecture on September 29, 2006, “People in poor countries are sick not primarily because they are poor but because of other social organizational failures, including health delivery, which are not automatically ameliorated by higher income.” This analysis concurs with classic studies of the array of societal factors explaining good health in poor settings such as Cuba and Kerala State in India. Analyses conducted over the past three decades indeed show that rapid health improvement is possible in very different contexts. That some countries continue to lag far behind can be understood through a comparison of regional differences in progress in terms of life expectancy over this period (Fig. 13e-3). While most regions have made impressive progress, sub-Saharan Africa and the former Soviet states have seen stagnation and even reversals.

FIGURE 13e-3 Regional trends in life expectancy. CEE and CIS, Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States; OECD, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (Source: World Health Organization: Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report, 2008.)

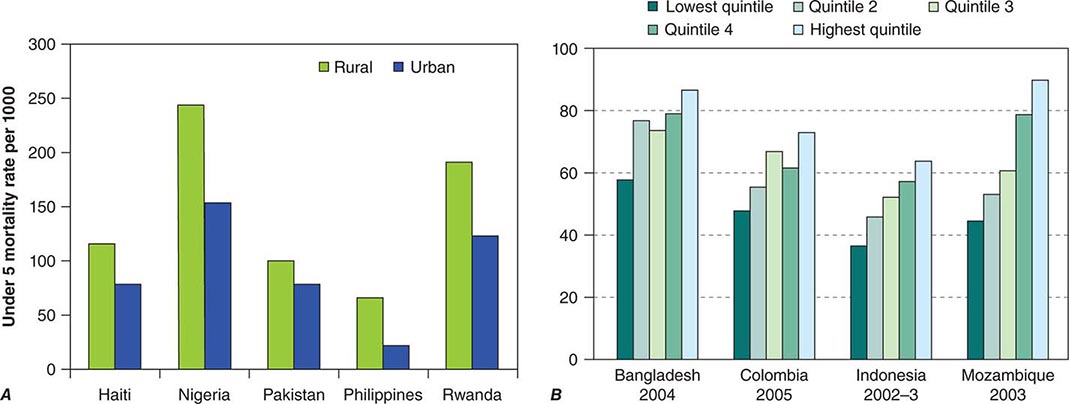

As average levels of health vary across regions and countries, so too do they vary within countries (Fig. 13e-4). Indeed, disparities within countries are often greater than those between high-income and low-income countries. For example, if low- and middle-income countries could reduce their overall childhood mortality rate to that of the richest one-fifth of their populations, global childhood mortality could be decreased by 40%. Disparities in health are mostly a result of social and economic factors such as daily living conditions, access to resources, and ability to participate in life-affecting decisions. In most countries, the health care sector actually tends to exacerbate health inequalities (the “inverse-care law”); because of neglect and discrimination, poor and marginalized communities are much less likely to benefit from public health services than those that are better off. Reforming health systems toward people-centered primary care provides an opportunity to reverse these negative trends.

FIGURE 13e-4 A. Mortality of children under 5 years old, by place of residence, in five countries. (Source: Data from the World Health Organization.) B. Full basic immunization coverage (%), by income group. (Source: Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. World Health Report 2008.)

Health services have failed to make their contribution to reducing these pervasive social inequalities by ensuring universal access to existing, scientifically validated, low-cost interventions such as insecticide-treated bed nets for malaria, taxes on cigarettes, short-course chemotherapy for tuberculosis, antibiotic treatment for pneumonia, dietary modification and secondary prevention measures for high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels, and water treatment and oral rehydration therapy for diarrhea. Despite decades of “essential packages” and “basic” health campaigns, the effective implementation of what is already known to work appears (deceptively) to be difficult.

Recent analyses have begun to focus on “the how” (as opposed to “the what”) of health care delivery, exploring why health progress is slow and sluggish despite the abundant availability of proven interventions for health conditions in low- and middle-income countries. Three general categories of reasons are being identified: (1) shortfalls in performance of health systems; (2) stratifying social conditions; and (3) skews in science.

SHORTFALLS IN PERFORMANCE OF HEALTH SYSTEMS

Specific health problems often require the development of specific health interventions (e.g., tuberculosis requires short-course chemotherapy). However, the delivery of different interventions is often facilitated by a common set of resources or functions: money or financing, trained health workers, and facilities with reliable supplies fit for multiple purposes. Unfortunately, health systems in most low- and middle-income countries are largely dysfunctional at present.

In the large majority of low- and middle-income countries, the level of public financing for health is woefully insufficient: whereas high-income countries spend, on average, 7% of the gross domestic product on health, middle-income countries spend <4% and low-income countries <3%. External financing for health through various donor channels has grown significantly over time. While these funds for health are significant (~$20 billion [U.S.] in 2008 for low- and middle-income countries), they represent <2% of total health expenditures in low- and middle-income countries and hence are neither a sufficient nor a long-term solution to chronic underfinancing. In Africa, 70% of health expenditures come from domestic sources. The predominant form of health care financing—charging patients at the point of service—is the least efficient and the most inequitable, tipping millions of households into poverty annually.

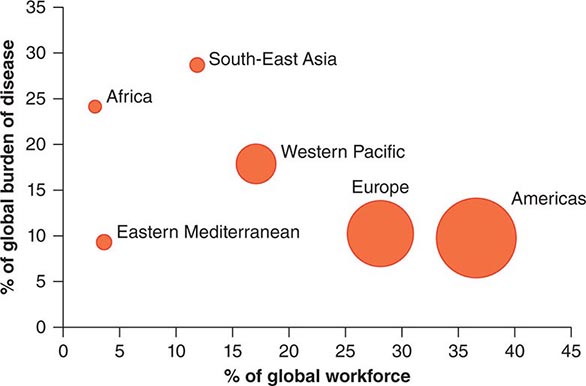

Health workers, who represent another critical resource, are often inadequately trained and supported in their work. Recent estimates indicate a shortage of >4 million health workers, constituting a crisis that is greatly exacerbated by the migration of health workers from low- and middle-income countries to high-income countries. Sub-Saharan Africa carries 24% of the global disease burden but has only 3% of the health workforce (Fig. 13e-5). The International Organization for Migration estimated in 2006 that there were more Ethiopian physicians practicing in Chicago than in Ethiopia itself.

FIGURE 13e-5 Global burden of disease and health workforce. (Source: World Health Organization: Working Together for Health, 2006.)

Critical diagnostics and drugs often do not reach patients in need because of supply-chain failures. Moreover, facilities fail to provide safe care: new evidence suggests much higher rates of adverse events among hospitalized patients in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. Weak government planning, regulatory, monitoring, and evaluation capacities are associated with rampant, unregulated commercialization of health services and chaotic fragmentation of these services as donors “push” their respective priority programs. With such fragile foundations, it is not surprising that low-cost, affordable, validated interventions are not reaching those who need them.

STRATIFYING SOCIAL CONDITIONS

Health care delivery systems do not exist in a vacuum but rather are embedded in a complex of social and economic forces that often stratify opportunities for health unfairly. Most worrisome are the pervasive forces of social inequality that serve to marginalize populations with disproportionately large health needs (e.g., the urban poor; illiterate mothers). Why should a poor slum dweller with no income be expected to come up with the money for a bus fare needed to travel to a clinic to learn the results of a sputum test for tuberculosis? How can a mother living in a remote rural village and caring for an infant with febrile convulsions find the means to get her child to appropriate care? Shaky or nonexistent social security systems, dangerous work environments, isolated communities with little or no infrastructure, and systematic discrimination against minorities are among the myriad forces with which efforts for more equitable health care delivery must contend.

SKEWS IN SCIENCE

While science has yielded enormous breakthroughs in health in high-income countries, with some spillover to low- and middle-income countries, many important health problems continue to affect primarily low- and middle-income countries whose research and development investments are deplorably inadequate. The past decade has seen growing efforts to right this imbalance with research and development investment for new drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics that effectively cater to the specific health needs of populations in low- and middle-income countries. For example, the Medicines for Malaria Venture has revitalized a previously “dry” pipeline for new malaria drugs. This is but one of many such efforts, but much more needs to be done.

As discussed above, the primary constraint on better health in low- and middle-income countries is related less to the availability of health technologies and more to their effective delivery. Underlying these systems and social challenges to greater equity in health is a major bias regarding what constitutes legitimate “science” to improve health equity. The lion’s share of health research financing is channeled toward the development of new technologies—drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics; in contrast, virtually no resources are directed toward research on how health care delivery systems can become more reliable and overcome adverse social conditions. The complexity of systems and social context is such that this issue of delivery requires an enormous investment in terms not only of money but also of scientific rigor, with the development of new research methods and measures and the attainment of greater legitimacy in the mainstream scientific establishment.

These common challenges to low- and middle-income countries partly explain the resurgence of interest in the primary health care approach. In some countries (mostly middle-income), significant progress has been made in expanding coverage by health systems based on primary care and even in improving indicators of population health. More countries are embarking on the creation of primary care services despite the challenges that exist, particularly in low-income countries. Even when these challenges are acknowledged, there are many reasons for optimism that low- and middle-income countries can accelerate progress in building primary care.

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The new millennium has seen a resurgence of interest in primary health care as a means of addressing global health challenges. This interest has been driven by many of the same issues that led to the Declaration of Alma Ata: rapidly increasing disparities in health between and within countries, spiraling costs of health care at a time when many people lack quality care, dissatisfaction of communities with the care they are able to access, and failure to address changes in health threats, especially noncommunicable disease epidemics. These challenges require a comprehensive approach and strong health systems with effective primary care. Global health development agencies have recognized that sustaining gains in public health priorities such as HIV/AIDS requires not only robust health systems but also the tackling of social and economic factors related to disease incidence and progression. Weak health systems have proved a major obstacle to delivering new technologies, such as antiretroviral therapy, to all who need them. Changing disease patterns have led to a demand for health systems that can treat people as individuals whether or not they present to a health facility with the public health “priority” (e.g., HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis) to which that facility is targeted. We discuss experiences in low- and middle-income countries in relation to primary care in greater detail below. First, we consider the features of primary health care and primary care as currently understood.

REVITALIZATION OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

At the 2009 World Health Assembly (an annual meeting of all countries to discuss the work of the World Health Organization [WHO]), a resolution was passed reaffirming the principles of the Declaration of Alma Ata and the need for national health systems to be based on primary health care. This resolution did not suggest that nothing had changed in the intervening 30 years since the declaration, nor did it dispute that its prescription needed reframing in light of changing public health needs. The 2008 WHO World Health Report describes how a primary health care approach is necessary “now more than ever” to address global health priorities, especially in terms of disparities and new health challenges. As discussed below, this report highlights four broad areas in which reform is required (Fig. 13e-6). One of these areas—the need to organize health care so that it places the needs of people first—essentially relates to the necessity for strong primary care in health systems and what this requirement entails. The other three areas also relate to primary care. All four areas require action to move health systems in a direction that will reduce disparities and increase the satisfaction of those they serve. The World Health Report’s recommendations present a vision of primary health care that is based on the principles of Alma Ata but that differs from many attempts to implement primary health care in the 1970s and 1980s.

FIGURE 13e-6 The four reforms of primary health care renewal. (Source: World Health Organization: Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. World Health Report 2008.)

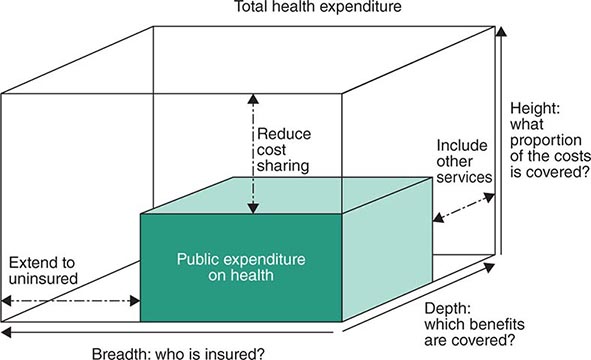

Universal Coverage Reforms to Improve Health Equity Despite progress in many countries, most people in the world can receive health care services only if they can pay at the point of service. Disparities in health are caused not only by a lack of access to necessary health services but also by the impact of expenditure on health. More than 100 million people are driven into poverty each year by health care costs, with countless others deterred from accessing services at all. Moving toward prepayment financing systems for universal coverage, which ensure access to a comprehensive package of services according to need without precipitating economic ruin, is therefore emerging as a major priority in low- and middle-income countries. Increasing coverage of health services can be considered in terms of three axes: the proportion of the population covered, the range of services underwritten, and the percentage of costs paid (Fig. 13e-7). Moving toward universal coverage requires ensuring the availability of health care services to all, eliminating barriers to access, and organizing pooled financing mechanisms, such as taxation or insurance, to remove user fees at the point of service. It also requires measures beyond financing, including expansion of health services in poorly served areas, improvement in the quality of services provided to marginalized communities, and increased coverage of other social services that significantly affect health (e.g., education).

FIGURE 13e-7 Three ways of moving toward universal coverage.

Service Delivery Reforms to Make Health Systems People-Centered Health systems have often been organized around the needs of those who provide health care services, such as clinicians and policymakers. The result is a centralization of services or the provision of vertical programs that target single diseases. The principles of primary health care, including the development of primary care, reorient care around the needs of the people to whom services cater. This “people-centered” approach aims to provide health care that is both more effective and appropriate.

The increase in noncommunicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries offers a further stimulus for urgent reform of service delivery to improve chronic disease care. As discussed above, large numbers of people currently fail to receive relatively low-cost interventions that have reduced the incidence of these diseases in high-income countries. Delivery of these interventions requires health systems that can address multiple problems and manage people over a long period within their own communities, yet many low- and middle-income countries are only now starting to adapt and build primary care services that can address noncommunicable diseases and communicable diseases requiring chronic care. Even some countries (e.g., Iran) that have had significant success in reducing communicable diseases and improving child survival have been slow to adapt their health systems to rapidly accelerating noncommunicable disease epidemics.

People-centered care requires a safe, comprehensive, and integrated response to the needs of those presenting to health systems, with treatment at the first point of contact or referral to appropriate services. Because no discrete boundary separates people’s needs for health promotion, curative interventions, and rehabilitation services across different diseases, primary care services must address all presenting problems in a unified way. Meeting people’s needs also involves improved communication between patients and their clinicians, who must take the time to understand the impact of the patients’ social context on the problems they present with. This enhanced understanding is made possible by improvements in the continuity of care so that responsibility transcends the limited time people spend in health care facilities. Primary care plays a vital role in navigating people through the health system; when people are referred elsewhere for services, primary care providers must monitor the resulting consultations and perform follow-up. All too often, people do not receive the benefit of complex interventions undertaken in hospitals because they lose contact with the health care system once discharged. Comprehensiveness and continuity of care are best achieved by ensuring that people have an ongoing personal relationship with a care team.

Public Policy Reforms to Promote and Protect the Health of Communities Public policies in sectors other than health care are essential to reduce disparities in health and to make progress toward global public health targets. The 2008 final report of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health provides an exhaustive review of the intersectoral policies required to address health inequities at the local, national, and global levels. Advances against major challenges such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, emerging pandemics, cardiovascular disease, cancers, and injuries require effective collaboration with sectors such as transport, housing, labor, agriculture, urban planning, trade, and energy. While tobacco control provides a striking example of what is possible if different sectors work together toward health goals, the lack of implementation of many evidence-based tobacco control measures in most countries just as clearly illustrates the difficulties encountered in such intersectoral work and the unrealized potential of public policies to improve health. At the local level, primary care services can help enact health-promoting public policies in other sectors.

Leadership Reforms to Make Health Authorities More Responsive The Declaration of Alma Ata emphasized the importance of participation by people in their own health care. In fact, participation is important at all levels of decision-making. Contemporary health challenges require new models of leadership that acknowledge the role of government in reducing disparities in health but that also recognize the many types of organizations that provide health care services. Governments need to guide and negotiate among these different groups, including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector, and to provide strong regulation where necessary. This difficult task requires a massive reinvestment in leadership and governance capacity, especially if action by different sectors is to be effectively implemented. Moreover, disadvantaged groups and other actors are increasingly expecting that their voices and health needs will be included in the decision-making process. The complex landscape for leadership at the national level is mirrored in many ways at the international or global level. The transnational character of health and the increasing interdependence of countries with respect to outbreak diseases, climate change, security, migration, and agriculture place a premium on more effective global health governance.

EXPERIENCES WITH PRIMARY CARE IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Aspects of the primary health care approach described above, with an emphasis on primary care services, have been implemented to varying degrees in many low- and middle-income countries over the past half-century. As discussed above, some of these experiences inspired and informed the Declaration of Alma Ata, which itself led many more countries to attempt to implement primary health care. This section describes the experiences of a selection of low- and middle-income countries in improving primary care services that have enhanced the health of their populations.

Before Alma Ata, few countries had attempted to develop primary health care on a national level. Rather, most focused on expanding primary care services to specific communities (often rural villages), making use of community volunteers to compensate for the absence of facility-based care. In contrast, in the post–World War II period, China invested in primary care on a national scale, and life expectancy doubled within roughly 20 years. The Chinese expansion of primary care services included a massive investment in infrastructure for public health (e.g., water and sanitation systems) linked to innovative use of community health workers. These “barefoot doctors” lived in and expanded care to rural villages. They received a basic level of training that enabled them to provide immunizations, maternal care, and basic medical interventions, including the use of antibiotics. Through the work of the barefoot doctors, China brought low-cost universal basic health care coverage to its entire population, most of which had previously had no access to these services.

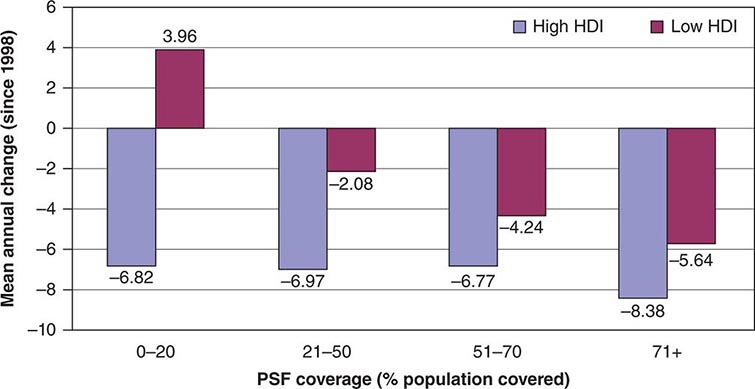

In 1982, the Rockefeller Foundation convened a conference to review the experiences of China along with those of Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, and the state of Kerala in India. In all of these locations, good health care at low cost appeared to have been achieved. Despite lower levels of economic development and health spending, all of these jurisdictions, along with Cuba, had health indicators approaching—or in some cases exceeding—those of developed countries. Analysis of these experiences revealed a common emphasis on primary care services, with expansion of care to the entire population free of charge or at low cost, combined with community participation in decision-making about health services and coordinated work in different sectors (especially education) toward health goals. During the three decades since the Rockefeller meeting, some of these countries have built on this progress, while others have experienced setbacks. Recent experiences in developing primary care services show that the same combination of features is necessary for success. For example, Brazil—a large country with a dispersed population—has made major strides in increasing the availability of health care in the past quarter century. In this millennium, the Brazilian Family Health Program has expanded progressively across the country, with almost all areas now covered. This program provides communities with free access to primary care teams made up of primary care physicians, community health workers, nurses, dentists, obstetricians, and pediatricians. These teams are responsible for the provision of primary care to all people in a specified geographic area—not only those who access health clinics. Moreover, individual community health workers are responsible for a named list of people within the area covered by the primary care team. Problems with access to health care persist in Brazil, especially in isolated areas and urban slums. However, solid evidence indicates that the Family Health Program has already contributed to impressive gains in population health, particularly in terms of childhood mortality and health inequities. In fact, this program has already had an especially marked impact on childhood mortality reduction in less developed areas (Fig. 13e-8).

FIGURE 13e-8 Improvements in childhood mortality following the Family Health Program in Brazil. HDI, Human Development Index; PSF, Program Saúde da Família (Family Health Program). (Source: Ministry of Health, Brazil.)

Chile has also built on its existing primary care services in the past decade, aiming to improve the quality of care and the extent of coverage in remote areas, above all for disadvantaged populations. This effort has been made in concert with measures aimed at reducing social inequalities and fostering development, including social welfare benefits for families and disadvantaged groups and increased access to early-childhood educational facilities. As in Brazil, these steps have improved maternal and child health and have reduced health inequities. In addition to directly enhancing primary care services, Brazil and Chile have instituted measures to increase both the accountability of health providers and the participation of communities in decision-making. In Brazil, national and regional health assemblies with high levels of public participation are integral parts of the health policy–making process. Chile has instituted a patient’s charter that explicitly specifies the rights of patients in terms of the range of services to which they are entitled.

Other countries that have made recent progress with primary health care include Bangladesh, one of the poorest countries in the world. Since achieving its independence from Pakistan in 1971, Bangladesh has seen a dramatic increase in life expectancy, and childhood mortality rates are now lower than those in neighboring nations such as India and Pakistan. The expansion of access to primary health care services has played a major role in these achievements. This progress has been spearheaded by a vibrant NGO community that has focused its attention on improving the lives and livelihoods of poor women and their families through innovative and integrated microcredit, education, and primary care programs.

The above examples, along with others from the past 30 years in countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Portugal, and Oman, illustrate how the implementation of a primary health care approach, with a greater emphasis on primary care, has led to better access to health care services—a trend that has not been seen in many other low- and middle-income countries. This trend, in turn, has contributed to improvements in population health and reductions in health inequities. However, as these nations have progressed, other countries have shown how previous gains in primary care can easily be eroded. In sub-Saharan Africa, undermining of primary care services has contributed to catastrophic reversals in health outcomes catalyzed by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Countries such as Botswana and Zimbabwe implemented primary health care strategies in the 1980s, increasing access to care and making impressive gains in child health. Both countries have since been severely affected by HIV/AIDS, with pronounced decreases in life expectancy. However, Zimbabwe has also seen political turmoil, a decline of health and other social services, and the flight of health personnel, whereas Botswana has maintained primary care services to a greater extent and has managed to organize widespread access to antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV/AIDS. Zimbabwe’s health situation has therefore become more desperate than that in Botswana.

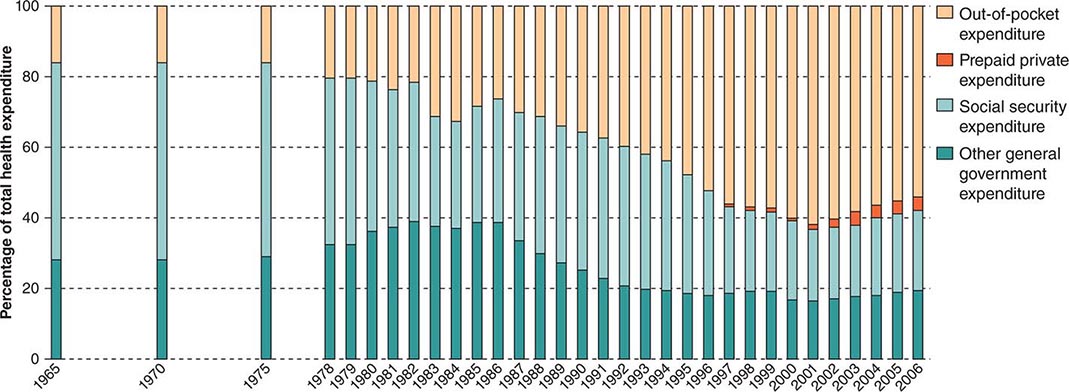

China provides a particularly striking example of how changes in health policy relevant to the organization of health systems (Fig. 13e-9) can have rapid, far-reaching consequences for population health. Even as the 1982 Rockefeller conference was celebrating China’s achievements in primary care, its health system was unraveling. The decision to open up the economy in the early 1980s led to rapid privatization of the health sector and the breakdown of universal health coverage. As a result, by the end of the 1980s, most people, especially the poorer segments of the population, were paying directly out of pocket for health care, and almost no Chinese had insurance—a dramatic transformation. The “barefoot doctor” schemes collapsed, and the population either turned to care paid for at hospitals or simply became unable to access care. This undermining of access to primary care services in the Chinese system and the resulting increase in impoverishment due to illness contributed to the stagnation of progress in health in China at the same time that incomes in that country increased at an unprecedented rate. Reversals in primary care have meant that China now increasingly faces health care issues similar to those faced by India. In both countries, rapid economic growth has been linked to lifestyle changes and noncommunicable disease epidemics. The health care systems of the two nations share two negative features that are common when primary care is weak: a disproportionate focus on specialty services provided in hospitals and unregulated commercialization of health services. China and India have both seen expansion of private hospital services that cater to middle-class and urban populations who can afford care; at the same time, hundreds of millions of people in rural areas now struggle to access the most basic services. Even in the former groups, a lack of primary care services has been associated with late presentation with illness and with insufficient investment in primary prevention approaches. This neglect of prevention poses a risk of large-scale epidemics of cardiovascular disease, which could endanger continued economic growth. In addition, the health systems of both countries now depend for the majority of their funding on out-of-pocket payments by people when they use services. Thus substantial proportions of the population must sacrifice other essential goods as a result of health expenditure and may even be driven into poverty by this cost. The commercial nature of health services with inadequate or no regulation has also led to the proliferation of charlatan providers, inappropriate care, and pressure for people to pay for expensive and sometimes unnecessary care. Commercial providers have limited incentives to use interventions (including public health measures) that cannot be charged for or that are what the person who is paying can afford.

FIGURE 13e-9 Changes in source of health expenditure in China over the past 40 years. (Source: World Health Organization: Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. World Health Report 2008.)

Faced with these problems, China and India have implemented measures to strengthen primary health care. China has increased government funding of health care, has taken steps toward restoring health insurance, and has enacted a target of universal access to primary care services. India has similarly mobilized funding to greatly expand primary care services in rural areas and is now duplicating this process in urban settings. Both countries are increasingly using public resources from their growing economies to fund primary care services.

These encouraging trends are illustrative of new opportunities to implement a primary health care approach and strengthen primary care services in low- and middle-income countries. Brazil, India, China, and Chile are being joined by many other low- and middle-income countries, including Indonesia, Mexico, the Philippines, Turkey, Rwanda, Ethiopia, South Africa, and Ghana, in ambitious initiatives mobilizing new resources to move toward universal coverage of health services at affordable cost.

OPPORTUNITIES TO BUILD PRIMARY CARE IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Global public health targets will not be met unless health systems are significantly strengthened. More money is currently being spent on health than ever before. In 2005, global health spending totaled $5.1 trillion (U.S.)—double the amount spent a decade earlier. Although most expenditure occurs in high-income countries, spending in many emerging middle-income countries has rapidly accelerated, as has the allocation of monies for this purpose by both governments in and donors to low-income countries. These twin trends—greater emphasis on building health systems based on primary care and allotment of more money for health care—provide opportunities to address many of the challenges discussed above in low- and middle-income countries.

Accelerating progress requires a better understanding of how global health initiatives can more effectively facilitate the development of primary care in low-income countries. A review by the WHO Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group looked at programs funded by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI); the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); and the World Bank (on HIV/AIDS). This group found that global health initiatives had improved access to and quality of the targeted health services and had led to better information systems and more adequate financing. The review also identified the need for better alignment of global health initiatives with other national health priorities and systematic exploitation of potential synergies. If global health initiatives implement programs that work in tandem with other components of national health systems without undermining staffing and procurement of supplies, they have the potential to contribute substantially to the capacity of health systems to provide comprehensive primary care services.

Even in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, global health initiatives continue to draw significant funding. In 2009, for example, U.S. President Barack Obama announced increasing development assistance from the United States for global health, earmarking $63 billion over the period 2009–2014 for a Global Health Initiative. New funding is also promised through a range of other initiatives focusing particularly on maternal and child health in low-income countries. The general trend is to coordinate this funding in order to reduce fragmentation of national health systems and to concentrate more on strengthening these systems. Comprehensive primary care in low-income countries must inevitably deal with the rapid emergence of chronic diseases and the growing prominence of injury-related health problems; thus, international health development assistance must become more responsive to these needs.

Beyond the new streams of funding for health services, other opportunities exist. Increased social participation in health systems can help build primary care services. In many countries, political pressure from community advocates for more holistic and accountable care as well as entrepreneurial initiatives to scale up community-based services through NGOs have accelerated progress in primary care without major increases in funding. Participation of the population in the provision of health care services and in relevant decision-making often drives services to cater to people’s needs as a whole rather than to narrow public health priorities.

Participation and innovation can help address critical issues related to the health workforce in low- and middle-income countries by establishing effective people-centered primary care services. Many primary care services do not need to be delivered by a physician or a nurse. Multidisciplinary teams can include paid community workers who have access to a physician if necessary but who can provide a range of health services on their own. In Ethiopia, more than 30,000 community health workers have been trained and deployed to improve access to primary care services, and there is increasing evidence that this measure is contributing to better health outcomes. In India, more than 600,000 community health advocates have been recruited as part of expanded rural primary care services. In Niger, the deployment of community health workers to deliver essential child health interventions (as a component of integrated community case management) has had impressive results in reducing childhood mortality and decreasing disparities. After the Declaration of Alma Ata, experiences with community health workers were mixed, with particular problems about levels of training and lack of payment. Current endeavors are not immune from these concerns. However, with access to physician support and the deployment of teams, some of these concerns may be addressed. Growing evidence from many countries indicates that shifting appropriate tasks to primary care workers who have had shorter, less expensive training than physicians will be essential to address the human resources crisis.

Finally, recent improvements in information and communication technologies, particularly mobile phone and Internet systems, have created the potential for systematic implementation of e-health, telemedicine, and improved health data initiatives in low- and middle-income countries. These developments raise the tantalizing possibility that health systems in these countries, which have long lagged behind those in high-income countries but are less encumbered by legacy systems that have proved hard to modernize in many settings, could leapfrog their wealthier counterparts in exploiting these technologies. Although the challenges posed by poor or absent infrastructure and investment in many low- and middle-income countries cannot be underestimated and will need to be addressed to make this possibility a reality, the rapid rollout of mobile networks and their use for health and other social services in many low-income countries where access to fixed telephone lines was previously very limited offer great promise in building primary care services in low- and middle-income countries.

CONCLUSION

As concern continues to mount about glaring inequities in global health, there is a growing commitment to redress these egregious shortfalls, as exemplified by global mobilization around the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals and the early discussions on what targets should build on these goals in the post-2015 era. This commitment begins first and foremost with a clear vision of the fundamental importance of health in all countries, regardless of income. The values of health and health equity are shared across all borders, and primary health care provides a framework for their effective translation across all contexts.

The translation of these fundamental values has its roots in four types of reforms that reflect the distinct but interlinked challenges of (re)orienting a society’s resources on the basis of its citizens’ health needs: (1) organizing health care services around the needs of people and communities; (2) harnessing services and sectors beyond health care to promote and protect health more effectively; (3) establishing sustainable and equitable financing mechanisms for universal coverage; and (4) investing in effective leadership of the whole of society. This common primary health care agenda highlights the striking similarity, despite enormous differences in context, in the nature and direction of the reforms that national health systems must undertake to promote greater equity in health. This shared agenda is complemented by the growing reality of global health interconnectedness due, for example, to shared microbial threats, bridging of ethnolinguistic diversity, flows in migrant health workers, and mobilization of global funds to support the neediest populations. Embracing solidarity in global health while strengthening health systems through a primary health care approach is fundamental to sustained progress in global health.

1Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era (1996).

14e |

Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Health Practices |

The search for health includes many beliefs and practices that are outside conventional medicine. Physicians are important sources for information and guidance about health matters, but our patients also rely on a wide range of other sources including family and friends, cultural traditions, alternative practitioners, and increasingly the Internet, popular media, and advertising. It is essential for physicians to understand what patients are doing to seek health, as this understanding is important to harness potential benefits and to help patients avoid harm.

DEFINITIONS AND SCOPE

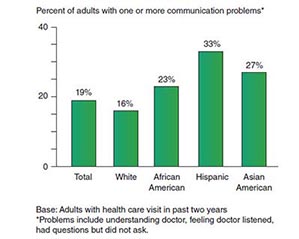

The phrase complementary and alternative medicine is used to describe a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that have historic origins outside mainstream medicine. Most of these practices are used together with conventional therapies and therefore have been called complementary to distinguish them from alternative practices, those used as a substitute for standard care. Use of dietary supplements; mind-body practices such as acupuncture, massage, meditation, and hypnosis; and care from a traditional healer all fall under this umbrella. Brief definitions for some of the common complementary and alternative health practices are provided in Table 14e-1. Although some complementary health practices are implemented by a complementary health care provider such as a chiropractor, acupuncturist, or naturopathic practitioner, or by a physician, many of these practices are undertaken as “self-care.” Most are paid for out of pocket.

|

TERMINOLOGY OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICAL PRACTICES |