Chapter 6 The sacrum

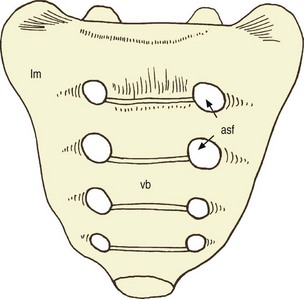

Its most obvious features are its triangular shape and its curvature. It has a broad, thick upper end but tapers to a blunt point inferiorly (Fig. 6.1). It has a relatively smooth anterior surface that is concave, and a rough posterior surface that is convex. Perforating its anterior surface is a series of paired holes, known as the anterior sacral foramina. Perforating its posterior surface is a corresponding series of holes, known as the posterior sacral foramina.

Particular features

In the midline anteriorly, the sacrum exhibits rectangular regions that resemble vertebral bodies embedded within the body of the sacrum (see Fig. 6.1). The top and bottom surfaces of each are marked by transverse ridges between which lie linear regions that resemble narrow intervertebral discs that have ossified. Laterally, bars of bone pass laterally from the vertebral bodies, above and below the anterior sacral foramina. Beyond the foramina, the bars expand, effectively into transverse processes. Lateral to the foramina, consecutive transverse processes fuse with one another, and constitute the lateral mass of the sacrum.

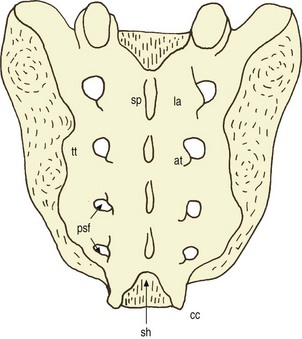

Posteriorly, the posterior elements of the fused vertebrae are evident (Fig. 6.2). Along the midline, a series of prominences represent the spinous processes of the fused, sacral vertebrae. That of the first sacral vertebra (S1) is most prominent; at successively lower levels the spinous processes become less prominent. The line of spinous processes forms what is known as the median sacral crest. The laminae of the fifth sacral vertebrae fail to meet in the midline, and a fifth sacral spinous process is not formed. The defect in its place is known as the sacral hiatus. Lateral to the spinous processes, plates of bone extend laterally as far as the posterior sacral foramina. These represent the laminae of the sacral vertebrae, but consecutive laminae are fused with one another, there being no ligamentum flavum at sacral levels. Opposite the inferomedial corner of each posterior sacral foramen, the junction of consecutive laminae is marked by a tubercle that represents a fused sacral zygapophysial joint. The line of articular tubercles constitutes the intermediate crest of the sacrum. The tubercles of the S5 vertebra flank the sacral hiatus and form definitive right and left inferior articular process, called the sacral cornua, which articulate with the coccyx. The name is derived from the Latin cornu, meaning horn, because the cornua resemble little horns at the base of the sacrum.

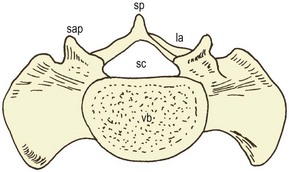

The superior surface of the sacrum presents an appearance similar to that of the L5 vertebra (Fig. 6.3). An area representing the S1 vertebral body is clearly outlined. A broad transverse process extends from it laterally on each side and resembles a wing. For this reason, each is known as an ala of the sacrum, derived from the Latin ala, meaning wing. Posteriorly, the superior surface presents a pair of superior articular processes, which, with the inferior articular processes of the L5 vertebra, form the lumbosacral, or L5–S1, zygapophysial joint. Posterior to the S1 vertebral body, the elements of a neural arch are evident. Short pedicles support the superior articular processes and continue medially as the laminae of S1. The arch surrounds the upper opening of the sacral canal, which is the continuation of the vertebral canal from lumbar levels.

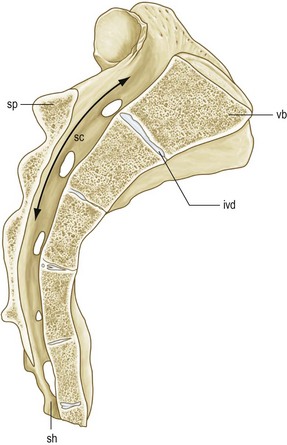

The sacral canal is patent throughout the entire length of the sacrum and is enclosed anteriorly by the sacral vertebral bodies, laterally by the transverse processes, and posteriorly by the laminae. Inferiorly, the canal opens through the sacral hiatus. Laterally, it communicates with the exterior of the sacrum through the anterior and posterior sacral foramina. A longitudinal section of the sacrum reveals the length of the sacral canal and the remains of the sacral intervertebral discs (Fig. 6.4).

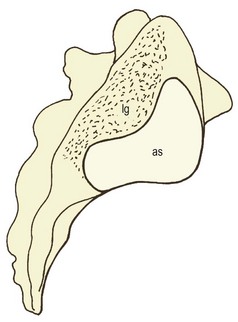

A lateral view of the sacrum (Fig. 6.5) shows that the transverse processes of the lower two segments are quite narrow from front to back, but those of the first three segments are thick. It is this section of the sacrum that articulates with the ilium. It presents two distinct areas: a smooth surface that has the shape of an ear, for which reason it is called the auricular surface; and an irregular, rougher area behind that. The auricular surface is the articular surface for the sacroiliac joint. The rough area is a ligamentous area that receives the fibres of the interosseous sacroiliac ligament.

Design features

The sacrum is massive but not because it bears the load of the vertebral column. After all, the L5 vertebra bears almost as much load as the sacrum but is considerably smaller. Rather, the sacrum is massive because it must be locked into the pelvis between the two ilia. The bulk of the sacrum lies in the bodies and transverse elements of its upper two segments and the upper part of the third segment. These segments are designed to allow the sacrum to be locked into the pelvic girdle and to transfer axial forces laterally into the lower limbs (and vice versa). Further aspects of this design are considered in the context of the sacroiliac joint (see Ch. 14).