2

The Role of the Physical Therapist Assistant in Physical Assessment

1. Apply the language of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice to physical assessment procedures.

2. Identify the common elements of examination, evaluation, and assessment.

3. Describe the role of the physical therapist assistant in the performance of physical assessment based on the physical therapy plan of care.

4. Discuss the role of the physical therapist assistant in data collection.

5. Explain methods of modifying the physical therapy plan of care or actions to be taken in response to physical assessment of the patient.

6. Identify critical elements to include with documentation of physical assessment.

7. Relate physical assessment to goals and outcomes of a physical therapy plan of care.

As any prospective or current student in the field of physical therapy is aware, changes in the profession are emerging rapidly. In an effort to bring physical therapy professionals to the “health care table” for discussion of legislative, regulatory, and reimbursement issues, the leaders of our profession are striving for standardization of terminology and recognition and application of evidence-based practice.4 Needless to say, controversy or at least animated debate occurs among interested parties any time such an in-depth self-scrutiny of a profession takes place. One significant element of this debate in physical therapy revolves around the physical therapist assistant’s (PTA’s) role in the profession, including how the PTA participates in the administration of the physical therapy plan of care, including selected interventions, data collection techniques, and the terminology associated with the PTA’s role. The purpose of this chapter is to summarize available standards and guidelines associated with the PTA’s role in physical therapy treatments and to discuss techniques and implications of selected interventions and their associated data collection techniques to be utilized for the patient with a musculoskeletal condition.

AMERICAN PHYSICAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION GUIDING DOCUMENTS

Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, Second Edition

The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, second edition (the Guide) is a tool that was developed by the American Physical Therapy Association in part to “…describe physical therapist practice in general; …standardize terminology used in and related to physical therapist practice; …delineate preferred practice patterns that will help physical therapists…promote appropriate utilization of health care services; [and] increase efficiency and reduce unwarranted variation in the provision of services….”4 The stated purpose of the Guide reads, in part, that it is: “…a resource not only for physical therapist clinicians, educators, researchers, and students, but [for] health care policy makers, administrators, managed care providers, third-party payers, and other professionals.”4 According to the Guide, the definition of the PTA is: “A technically educated health care provider who assists the physical therapist in the provision of selected physical therapy interventions.”4 Assessment is defined as “The measurement or quantification of a variable or the placement of a value on something.”4 Further, the Guide states, “Assessment should not be confused with examination or evaluation.”4 Examination involves preliminary gathering of data and performing various screens, tests, and measures to obtain a comprehensive base from which to make decisions about physical therapy needs for each individual patient, including the possibility of referral to another health care provider. Evaluation is the specific process reserved solely for the physical therapist (PT), in which clinical judgments are made from this base of data obtained during the examination.4

Standards of Ethical Conduct for the Physical Therapist Assistant

The Standards of Ethical Conduct for the Physical Therapist Assistant is a tool developed by the American Physical Therapy Association to delineate the ethical obligations of all PTAs.7 There are eight standards of ethical conduct for the PTA and they can be found in the “Membership and Leadership” section on APTA website (www.apta.org).

Professionalism in Physical Therapy: Core Values

The American Physical Therapy Association has also developed a list of values, known as core values, which reflect what one would call a professional in physical therapy. The core values include: accountability, altruism, compassion/caring, excellence, integrity, professional duty, and social responsibility.3 Each core value, along with its corresponding definition as defined by the APTA, can be found in the “Practice” section on the APTA website.

The Clinical Performance Instrument

The Clinical Performance Instrument (CPI), a uniform clinical education grading tool developed by the American Physical Therapy Association,5 includes the following criteria related to the PTA’s role in clinical problem solving and judgments, data collection, and assessment techniques:

“Participates in patient status judgments∗ within the clinical environment based on the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” (criterion #9)

“Participates in patient status judgments∗ within the clinical environment based on the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” (criterion #9)

“Obtains accurate information by performing selected data collection† consistent with the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” (criterion #10)

“Obtains accurate information by performing selected data collection† consistent with the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” (criterion #10)

“Discusses the need for modifications to the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” (criterion #11)

“Discusses the need for modifications to the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” (criterion #11)

A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Assistant Education: Version 2007

A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Assistant Education: Version 20072 (the Model) is a consensus-based document developed by the American Physical Therapy Association. Briefly, the Model was designed to provide a representation of all of the elements that provide the foundation for the development and evaluation of educational programs preparing PTAs.2 According to the Model, PTAs “…implement selected components of patient/client interventions and obtain data related to that intervention; make modifications in selected interventions either to progress the patient/client as directed by the physical therapist or to ensure patient/client safety and comfort.”2

Each performance expectation theme includes educational outcomes, terminal behavioral objectives, and instructional objectives to be achieved in the classroom and clinic.

Frequently, the response to the question about the difference between PTs and PTAs is simply, “PTAs don’t do evaluations.” Considering the elements of judgment and decision making involved with evaluation and from the preceding discussion, does this imply that the PTA does not exercise judgment or make decisions? Of course not. However, the judgments and subsequent decisions of the PTA are made within the context of the existing physical therapy plan of care, established by the supervising PT through the examination and evaluation process. This process occurs on an ongoing basis.23 Without effective data collection and reporting by the PTA, the PT would lack key information on which this data management process relies.23

It may be helpful to consider the functions of data collection and patient management as integral parts of managing a patient’s physical therapy case, which is a dynamic process as illustrated in the APTA’s “Problem-Solving Algorithm Utilized by PTAs in Patient/Client Intervention” (see Figure 1-1).2

INFLAMMATION

What Is Inflammation?

General Contraindications and Precautions with Inflammation

In general, remember that inflammation is a reaction to tissue trauma or injury; the increased inflammatory reactions after exercise or other interventions may indicate that the intervention is too aggressive or contraindicated, resulting in new trauma or injury to healing tissues. Furthermore, responses to interventions between visits must also be assessed; a patient may report signs of increased inflammation up to 48 hours after an injury or intervention, particularly after administration of exercise or manual stretching techniques.19

Acute versus Chronic

Under normal circumstances, signs of acute inflammation persist for 4 to 6 days, assuming the precipitating condition, agent, or event is removed. In the initial 48 hours after tissue injury, the observable signs of inflammation are associated with the normal inflammatory vascular response to trauma.19 An important distinction to make is the definition of acute versus chronic in relation to the actual cause of injury or trauma. It is common for sources to refer to these tissue states in terms of time frames only, with the acute phase lasting 4 to 6 days and the chronic phase lasting 6 months to 1 year.19 A more useful way to consider inflammation incorporates the concept of whether there is real or impending tissue damage present. The significance of this designation relates to the PTA’s role in determining whether, based on the stage of inflammation present, certain interventions may be implemented or are contraindicated.28 If an intervention normally results in an inflammatory reaction, it is contraindicated when the tissue is in an acute inflammatory state that indicates ongoing tissue damage. For example, in the presence of acute inflammation (indicating an active state of injury, tissue damage, or early tissue healing), dynamic resistance exercises are contraindicated.19 However, the PTA also may proceed with interventions included in the plan of care that accelerate the inflammatory process if it has been determined that the original causal agent or condition no longer results in ongoing tissue damage. Contraindications related to specific diagnoses or associated with the application of specific physical agents are discussed elsewhere in this book.

During interventions involving range of motion (ROM) activities, the PTA also may note that the patient reports pain before tissue resistance is felt (before end ROM); this is an indication of acute inflammation.19 Pain reported at the same time end ROM is reached is indicative of a subacute inflammatory state, and pain reported as a stretching sensation at the limit of ROM is a sign of inflammation in the chronic state.19 If the PTA determines that the established plan of care includes interventions that are not appropriate for the apparent stage of inflammation, the PT must be consulted to adjust goals, time frames, or possibly the plan itself to ensure that the treatment does not contribute to a prolonged or abnormal state of inflammation.

TEMPERATURE

Both the degree of temperature elevation and duration of fever are relevant to diagnostic processes when elevated body temperature is evident. During the initial examination and evaluation, any abnormality in temperature, either locally or systemically, should be noted. The PTA’s role is then to note deviations from the examination findings, determine the length of time the fever has been present (through patient interview) and note other possible related signs and symptoms: rash, cough, complaints of sore throat, and so on. Also it should be noted if the patient reports any pattern of temperature changes, because this may have diagnostic implications for the PT or physician. Immediate implications include whether or not exercise or other interventions may be contraindicated and to what extent infection control issues must be addressed. Normal adult body temperature (oral measurement) ranges from 96.8° F to 99.5° F (36° C to 37.5° C).26 Temperature is affected by factors including age, time of day, emotions/stress, exercise, menstrual cycle, pregnancy, external environment, measurement site, and ingestion of warm or cold foods.26 Clinical signs and symptoms of fever vary based on the underlying cause and stage and may include general malaise, headache, increased pulse and respiratory rates, general chills, shivering, piloerection, loss of appetite, pale skin, nausea, irritability, restlessness, constipation, sweating, thirst, coated tongue, decreased urinary output, insomnia, and weakness.26 In the case of the presence of fever, the PTA must gather the related data, document it, and report it to the supervising PT. The data and report should include adequate information to enable the PT to respond appropriately, either in terms of immediate modification to the physical therapy plan of care or consultation with the medical team.

Fever and Exercise

In terms of exercise precautions, discretionary caution should be applied with any patient with a fever, because of stresses on the cardiopulmonary and immune systems and the possible further complications related to dehydration.14 The PTA must be familiar with specific exercise techniques (e.g., aquatic exercise) contraindicated in the presence of diseases transmitted via water or air.

Fever and Lymph Nodes

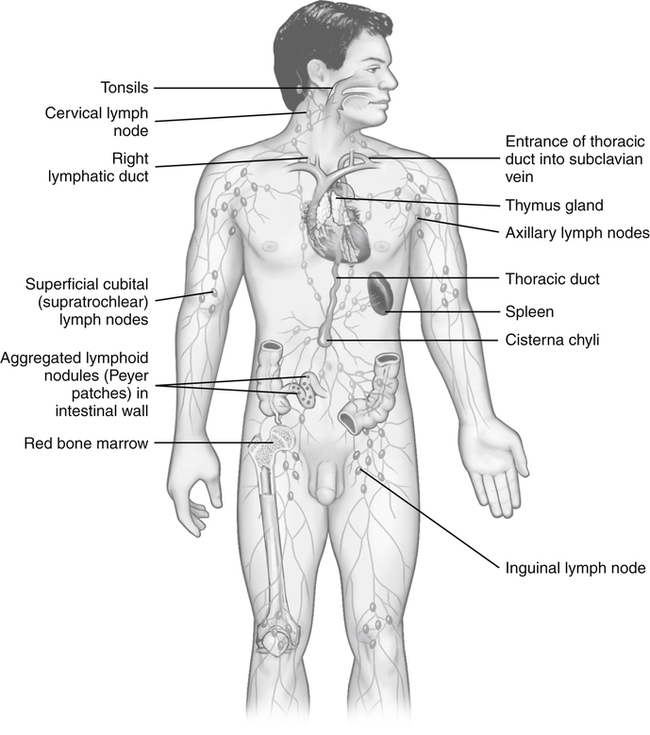

Another condition that may become readily apparent to the PTA in the course of carrying out elements of the physical therapy plan of care is tenderness or exquisite pain in particular regions of the body. The presence of tender or enlarged lymph nodes is of particular concern to the PTA who is performing soft-tissue interventions on a patient with an elevated body temperature (or otherwise). Figure 2-1 provides a visual reference for the location of lymph nodes. PTAs using hands-on techniques such as soft-tissue massage and manual stretching are incidentally afforded the opportunity during the course of treatment to assess for the presence of unusual conditions in areas of lymph node clusters (e.g., in the neck and axilla). Because these symptoms can signify the presence of potentially serious pathologic conditions, the presence of pain, tenderness or enlargement of lymph nodes are situations in which the PTA must consult with the supervising PT to pursue medical follow-up for definitive diagnosis.14 In addition, certain interventions are considered contraindicated if the patient has an underlying pathology related to changes in the lymph nodes.

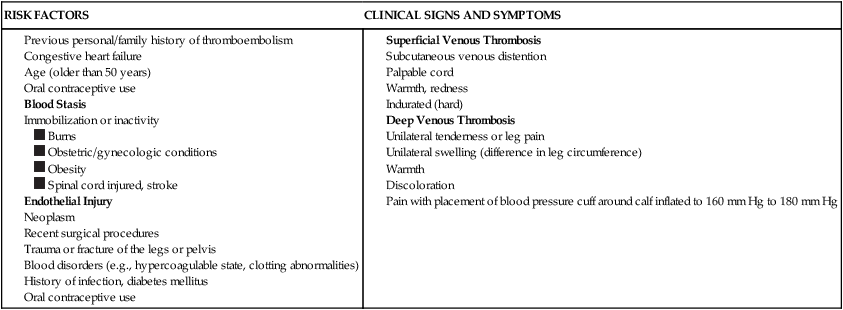

REDNESS AND SKIN COLOR CHANGES

Unexpected findings in terms of changes in skin color should be reported to the supervising PT for further evaluation. These changes include rashes or redness that appear as a streak originating from the site of injury. Red streaks may indicate an acute inflammation caused by a bacterial infection (streptococci, staphylococci, or both), resulting in acute inflammation of the lymph vessels.14 Redness along with superficial tenderness and hardness (induration) of the area may be a sign of superficial thrombophlebitis.14 These findings should be reported to the supervising PT because they may be a precursor to more serious conditions. A loss of skin color (paleness or pallor) associated with temperature changes, edema, or pain may be indicative of an occlusion in a blood vessel and warrants immediate medical referral. A commonly used quick assessment technique to rule out the presence of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is Homans’ sign, performed by gentle passive stretching of the ankle into full dorsiflexion and assessing for pain in the calf. Some clinicians also incorporate a gentle squeezing of calf musculature during the passive dorsiflexion to assess for tenderness. Other structures that are stretched during this test include the calf muscles and the Achilles tendon; thus a positive Homans’ sign may be noted in error if a patient has tightness or inflammation of these structures. Although Homans’ sign is still commonly assessed, it is considered an insensitive and nonspecific test, and is present in less than one third of all patients with a documented DVT, and more than 50% of patients with a positive Homans’ sign do not have evidence of venous thrombosis.14 Furthermore, a serious potential complication of a DVT is that a piece of the coagulated blood (the clot) may break free from the inside of the vessel wall as a result of the test (or otherwise) and travel through the bloodstream, lodging in a pulmonary artery, causing a life-threatening condition (pulmonary embolism). Therefore it is recommended that the PTA refrain from conducting the Homans’ test and be alert to the risk factors and the clinical signs and symptoms of a DVT as outlined in Box 2-1 and report these findings to the supervising PT for further investigation and possible immediate medical referral. The PTA should note that signs and symptoms are the same for a PE and a DVT.

From Goodman CC, Snyder TE: Differential diagnosis for physical therapists screening for referral, St. Louis, 2007, Saunders Elsevier, p. 312.

EDEMA

Edema refers to excessive pooling of fluid in the spaces between tissues (interstitial spaces).14 In relation to patients with orthopedic injuries or conditions, the main consideration for assessment by the PTA is measurement of the edematous part or extremity. Typically, the technique used to measure edema in an extremity is straightforward—use of a tape measure to obtain circumferential dimensions of the involved part. The data must be reliable and the measurement reproducible, regardless of who is conducting the assessment. To ensure this level of consistency, the PTA must use precisely the same landmarks as the evaluating PT. Specifically, palpable bony landmarks must be used as the starting standard reference point; then circumferential measurements can be taken at determined distances from that point. For example, to measure the lower leg, circumference measured with the tape measure at the inferior pole of the patella may be used as a reference point, with measurements then taken every 2 inches distally and at the ankle. One note of caution, the PTA must be careful to not pull the tape measure too tight when performing this skill. The skin should not have an indention if performing correctly. An example of a flow chart for recording circumferential measurements of the upper extremity is provided in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1

Sample Format for Documenting Edema

| UE | Right | Left |

| Axilla | _______inches | _______inches |

| 4” above elbow | _______inches | _______inches |

| 2” above elbow | _______inches | _______inches |

| Elbow∗ | _______inches | _______inches |

| 2” below elbow | _______inches | _______inches |

| 4” below elbow | _______inches | _______inches |

| Wrist∗ | _______inches | _______inches |

∗A standard for elbow could be from the cubital fossa around the elbow, crossing the olecranon process; a standard for wrist could be just distal to the radial and ulnar styloid processes.

A figure-of-eight technique may be used at the ankle to ascertain a gross estimate of generalized ankle edema.12,22,31 Refer to Box 2-2 for the steps involved in this procedure.

Another technique used to obtain a quantitative measure of edema in a limb involves immersing the limb into a specially designed container of fluid (a volumeter) and measuring the amount of water displaced.20 Karges and colleagues17 established correlations between different techniques of volumetric measurement but also emphasized the importance of ensuring reliability of the data for a given patient, in terms of employing a consistent technique for edema measurement of the same patient. In other words, as stated, the PTA must use the method of measurement, employing the same technique chosen by the evaluating PT.17,20

In addition to a quantitative measurement of edema through circumferential measurement or volumetrics, data relating to the quality of edema should be collected and documented by the PTA. Characteristics of edema that may be observed are described as brawny or pitting. Brawny edema refers to edema that feels hard, tough, or thick and leathery. This indurated quality is frequently associated with chronic inflammation or systemic pathologies involving fluid shift abnormalities (e.g., congestive heart failure [CHF]). Pitting edema is characterized by the formation of a sustained indentation when the swollen area is compressed.9,16 Pitting edema may be further quantified according to the scale in Table 2-2.

Table 2-2

Scale for Rating Pitting Edema

| Rating | Characteristics |

| 1+ | Barely perceptible depression |

| 2+ | Easily identified depression; depression takes +15 seconds for tissue to rebound |

| 3+ | Depression takes 15 to 30 seconds to rebound |

| 4+ | Depression lasts for 30 seconds or more |

From Kloth L, McCulloch J: Wound healing: alternatives in management, Philadelphia, 2002, FA Davis.

Unlike transient inflammatory reactions that may normally occur in response to certain physical therapy interventions, a significant increase in edema should be regarded as abnormal and reported accordingly. Upon first noticing edema in the extremity being treated, the PTA must determine if the swelling is confined to the involved extremity or if the contralateral extremity is also involved. If the opposite extremity is also edematous, this finding could indicate a systemic pathologic condition.14 For example, bilateral pitting edema of the distal lower extremities is a common manifestation in CHF, a relatively common diagnosis encountered among individuals with cardiac disease and those older than 65 years of age. Because this pathology is common among a significant population and it develops gradually, the PTA may play an important role in the diagnostic process via astute recognition of signs and symptoms associated with the onset of CHF. In addition to bilateral lower extremity pitting edema, the PTA also may note a decrease in tolerance to exercise (fatigue, shortness of breath, and muscle weakness). The presence of this clinical response necessitates prompt consultation with the supervising PT for medical diagnostic workup and possible subsequent modifications to the physical therapy plan of care.

A potentially serious condition involving edema is compartment syndrome. This condition occurs in anatomic compartments (of the calf or, less frequently, the antebrachium) as a result of increased fluids in an area tightly bound by fascia. Because fascia does not “give” to allow more space to accommodate this fluid buildup, this edema can compress nerves and blood vessels as they course through the compartment, leading to ischemia and possible nerve damage. Because the edema is contained within the compartment, the PTA should be alert to other associated signs and symptoms: history of blunt trauma, crush injury, or unaccustomed exercise; severe, persistent leg pain that is intensified when a stretch is applied to the involved muscles; swelling, severe tenderness, and palpable tension of the involved structures; paresthesia, paresis, and pulselessness.8 Immediate consultation with the supervising PT and possibly immediate medical referral are warranted if the signs and symptoms are noted.

PAIN

Changes in pain since last physical therapy visit or examination

Changes in pain since last physical therapy visit or examination

Responses of the patient in terms of how interventions to date or at present affect pain

Responses of the patient in terms of how interventions to date or at present affect pain

Patterns of pain (e.g., physical or temporal)

Patterns of pain (e.g., physical or temporal)

Modalities, types, or characteristics of pain (e.g., sharp or burning)

Modalities, types, or characteristics of pain (e.g., sharp or burning)

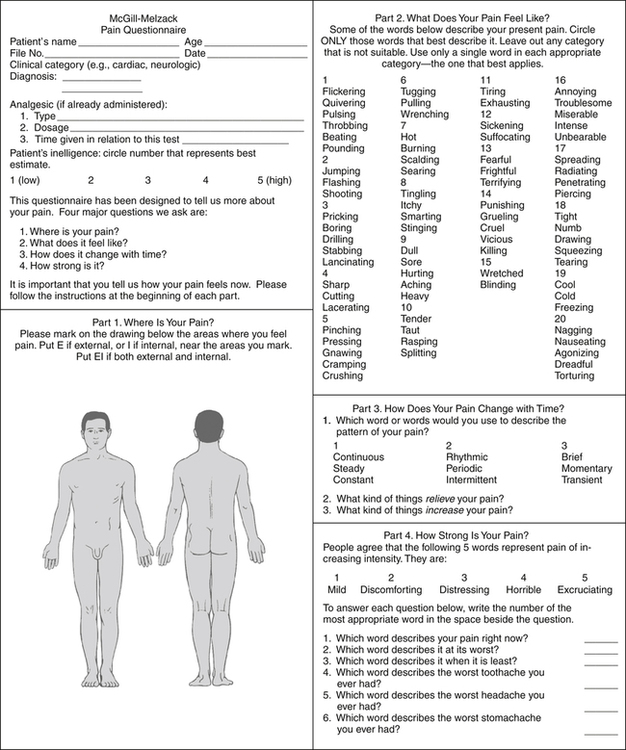

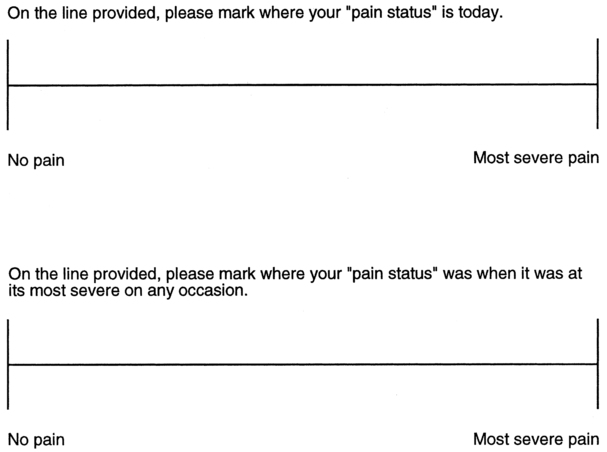

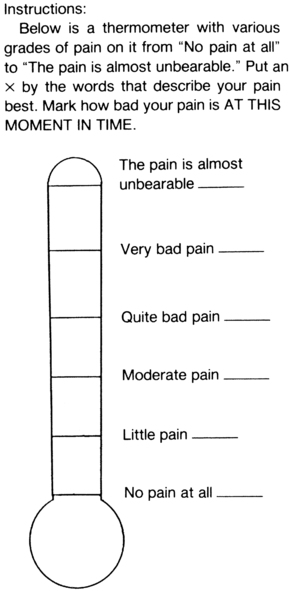

Several standardized instruments are available to record findings of pain assessment. As with all assessment and data collection techniques, the PTA must use the same instrument or same technique for recording data related to a patient’s pain complaints as was used by the supervising PT during the initial examination. Simple and commonly used tools are pain rating scales and visual analog scales that can be seen in Figures 2-2, 2-3, and 2-4.

During the course of carrying out elements of the supervising PT’s plan of care, the PTA may notice a change in the quality of a patient’s pain from more acute to chronic pain. As described in the section on inflammation, a chronic state is one in which the symptoms (pain in this case) persist for a period of time longer than expected, based on physiologic principles of tissue healing. Chronic pain has been described as that which lasts more than 3 months.24 Recall also that one descriptive feature of a chronic condition relates to the lack of real, ongoing, or pending tissue damage. In regard to pain, this circumstance also often coincides with complaints of pain that are nonspecific, diffuse, or indirectly proportional to the physical appearance or presentation of the patient.

“Red Flag” Pain Symptoms

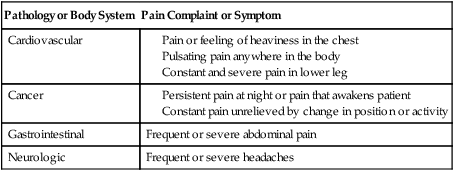

The PTA must also be keenly aware of pain that sends a “red flag” signal. In this case, the PTA should not proceed with any interventions or data collection techniques that are potentially contraindicated and should immediately report the findings to the supervising PT. Table 2-3 presents a summary of red flag or potentially serious pain conditions and the possible associated pathology or body system.

Table 2-3

| Pathology or Body System | Pain Complaint or Symptom |

| Cardiovascular |

Adapted from Magee DJ: Orthopedic physical assessment, ed 5, St. Louis, 2008, Saunders; Stith JS, Sahrmann SA, Dixon KK, et al: Curriculum to prepare diagnosticians in physical therapy, J Phys Ther Educ 9:50, 1995.

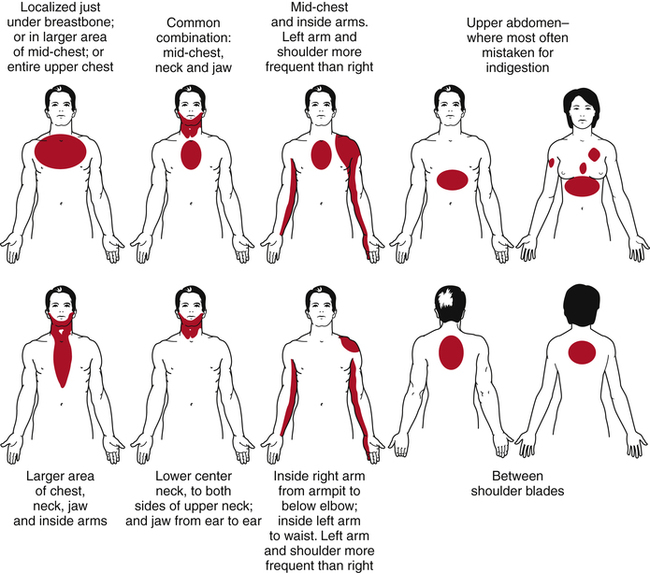

In addition to knowing the red flag symptoms described here, the PTA working with any client must be alert to signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction (MI, heart attack). Certain patterns of pain have been identified as early warning signs of a heart attack (Fig. 2-5). The PTA working with a patient exhibiting any of these patterns of pain should consult with the supervising PT right away for possible immediate medical referral. Concurrent symptoms of MI may include nausea, pallor, and profuse perspiration. Myocardial infarction may occur over a period of time and may be experienced while the patient is undergoing exertion or even at rest.

Intermittent Claudication

Another distinct pattern or type of pain that may manifest coincidentally with musculoskeletal symptoms or conditions is that of intermittent claudication, which is the term used to describe activity-related discomfort associated with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Intermittent claudication is typically described as aching or cramping that is localized in the region affected by the impaired circulation.14 Because it involves a systemic condition, it typically manifests bilaterally and usually involves the calves, thighs, or buttocks, areas that are often symptomatic with musculoskeletal pathologies.14 Once the aggravating activity is discontinued, it is characteristic for the symptoms of claudication (pain or cramping) to improve rapidly.

The assessment for intermittent claudication consists of determining what is referred to as claudication time. The basic protocols involve assessing maximal treadmill walking time, pain-free walking time, and walking time to severe claudication.11 As with other standardized tests and measures, the data collection technique employed by the PTA must be the same technique used by the supervising PT.

It is also possible that the PTA may be the first clinician to recognize the symptoms associated with undiagnosed peripheral arterial occlusive vascular disease in terms of the nature, characteristics, and location of symptoms as described. Other signs and symptoms that are consistent with PAD include pallor, decrease in peripheral pulses, sensory changes, and weakness of the involved area (distal to the site of blocked circulation).14 Diabetes mellitus and nonhealing wounds on the feet also are frequently associated with PAD.14 Obviously observation of the signs of undiagnosed PAD should be reported to the supervising PT immediately.

Referred Pain

Referred pain is defined as pain that is “felt in an area far from the site of the lesion, but supplied by the same or adjacent neural segments.”14 Referred pain can originate from any cutaneous, somatic, or visceral source and is commonly associated with problems of the musculoskeletal system. It is usually well localized but with indistinct boundaries, tends to be felt deeply, and radiates segmentally without crossing the midline.22 No objective sensory deficits (paresthesia, numbness, or weakness) are associated with referred pain.14,22

Visceral Pain

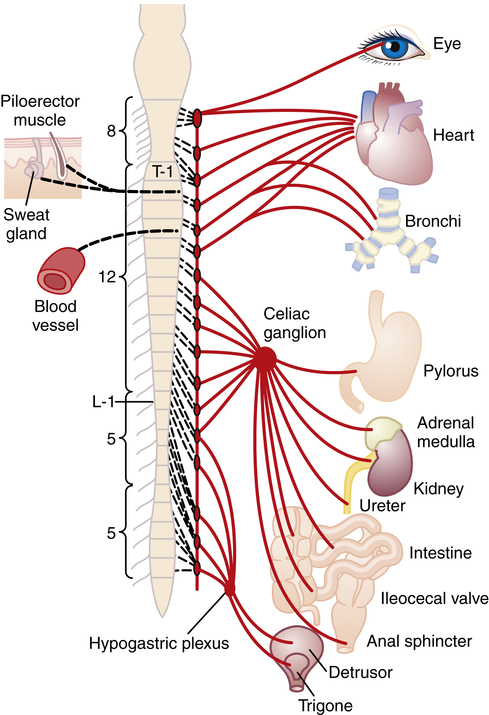

The term visceral pain refers to pain that originates from a body organ. The primary concerns for the PTA related to this type of pain are for the PTA to be aware of how visceral pain may manifest, and to report suspicious pain symptoms to the supervising PT. Often disease processes involving specific or multiple organs reveal themselves through a variety of symptoms and not just pain. However, it is quite possible for a patient to have more than one pathologic condition at the same time. In other words a patient with a confirmed diagnosis of herniated disc in the lumbar spine also could have some type of developing abdominal pathology. Pain of a visceral origin may present as musculoskeletal symptoms because of the innervation pattern of the involved organ. Visceral pain is not well localized secondary to viscera innervation being multisegemental. Additionally, isolation of visceral pain is difficult due to its correspondence to dermatomes from which the problem organ receives its innervation. Figure 2-6 provides a visual representation of innervation to major internal organs in terms of spinal levels of nerve supply. Note that the organs are supplied via plexuses or ganglia, resulting in innervation from multiple segmental levels. For this reason organ pain may be diffuse and difficult for the patient to localize, appearing as nonspecific musculoskeletal discomfort. In the case of disease processes that develop over time, the PTA must be alert to changes in the patient’s complaints of pain and reports from the patient of patterns that are not consistent with musculoskeletal conditions.

Trigger Points

“Trigger points are small, localized tender areas found within skeletal muscles, fascia, tendons, ligaments, periosteum, and pericapsular areas.”30 Trigger points are associated with musculoskeletal conditions such as temporomandibular joint dysfunction, cervical strain, fibromyalgia, and myofascial pain syndrome. The pain produced by trigger points is characterized by tenderness and a referred pattern of pain to palpation, usually in upper quarter or pelvic girdle muscles. According to an article in American Family Physician,1 “Palpation of a hypersensitive bundle or nodule of muscle fiber of harder than normal consistency is the physical finding typically associated with a trigger point. Palpation of the trigger point will elicit pain directly over the affected area or cause radiation of pain toward a zone of reference and a local twitch response.” If, during the process of applying hands-on soft-tissue interventions or passive exercises, the PTA notices signs and symptoms of possible trigger points that have not been previously documented, these findings should be documented and reported to the supervising PT.

VITAL SIGNS

Pulse (Heart Rate)

Heart rate should be measured at the time of evaluation to establish a baseline rate and subsequently when beginning any exercise program or new activity. Accepted values for normal heart rate in adults range from 60 to 100 beats per minute (BPM).10 Factors that influence heart rate include age, gender, emotional state, medications, exercise or conditioning level, and systemic or local heat.26

In addition to the quantitative measure, the quality of the pulse should be noted. Often in a setting where the PTA is working primarily with healthy clients (e.g., trained or conditioned athletes), it may be sufficient to perform a 6-second beat-count and multiply by 10 to quickly determine the cardiovascular response to an activity. However, if the PTA perceives any abnormal quality to the pulse, such as an irregular rhythm or a “thready” pulse (lacking distinct beats), the heart rate should be monitored for a full minute.26 In such a case, if the abnormality has not previously been noted, this finding should be reported to the supervising PT immediately. Otherwise, as in the case with other assessment procedures, the PTA should employ the same technique as the PT uses during the initial evaluation to enhance consistency and better determine any deviation from the baseline measure.

Textbooks commonly used by PTA educational programs offer specific guidelines for setting exercise intensity using heart rate as a determinant.10,19,26 An increase in the pulse of more than 20 BPM with activity that lasts for more than 3 minutes after rest should be reported to the supervising PT.14

Respiration

As with pulse, respirations should be assessed for both rate and quality. In the healthy adult, normal respiratory rate ranges from 12 to 20 breaths per minute.26 Variations in the range of normal respiration rate are expected among age groups. Other factors influencing respirations include age, body size, stature, exercise, body position, environment, emotions/stress and pharmacologic agents.26

Blood Pressure

Assessment of blood pressure provides an objective measurement of vascular resistance to blood flow at a given time. The pressure exerted by blood is influenced by various factors and conditions, including age and cardiac output, both of which are directly proportional to systolic blood pressure.26 Obviously, age is a nonmodifiable factor, so an increase in systolic blood pressure of elderly patients may not necessarily indicate an active pathologic process. As always, these findings should be noted in relation to the baseline measurement obtained by the supervising PT during the initial examination.

The PTA working with patients who have musculoskeletal dysfunction or impairment is most concerned with noting responses in blood pressure as new therapeutic activities are introduced or advanced during the course of progression through the established plan of care. Most notably, blood pressure is affected by exercise and activity level in the following ways. Cardiac output increases proportionally to increased physical activity.16 An even greater and potentially dangerous increase in blood pressure also may occur if the patient holds his or her breath during periods of exertion with exercise. Patients may do this subconsciously in an effort to increase the weight-bearing function of the abdominal cavity, which becomes more stable with an attempt at strong exhalation against a closed glottis, nose, and mouth.26 As noted in the discussion about pain, the PTA must be alert to the patient’s total response to interventions and data collection techniques. When the observant PTA notices that the patient is holding his or her breath during exertion, the patient should be educated in techniques to avoid this behavior. The PTA also may want to reassess blood pressure at this time, although the effect on blood pressure from this activity, known as the Valsalva maneuver, is transient. It is particularly critical that the Valsalva maneuver be avoided by patients with a known history of hypertension or cardiac disease.16

Another important blood pressure response that may occur during a physical therapy session is a sudden drop in blood pressure, called orthostatic hypotension. This rapid drop in blood pressure is associated with a sudden change in the patient’s position. It is most frequently the result of the patient being immobile or recumbent for prolonged periods of time, and baseline measurements should be determined before the initiation of upright activities. Signs of orthostatic hypotension include lightheadedness, weakness, dizziness, or diaphoresis.14 If not addressed (by returning the patient to at least a semireclined position), the patient may lose consciousness. Because of the rapid change in blood pressure, the PTA must be prepared to assess the blood pressure immediately upon the change in position. The blood pressure response is critical to obtain, record, and report because the symptoms associated with orthostatic hypotension can also be caused by other serious medical conditions.

Three final points should be noted by the student PTA. First, the PTA should check to be sure of any precautions or contraindications for the assessment of blood pressure that may be present. If the patient has a history of circulatory or lymphatic drainage compromise in one upper extremity, blood pressure must be assessed in the contralateral upper extremity.26 Second, as mentioned in relation to assessment of other vital signs, the PTA student should practice taking and monitoring blood pressure on a variety of healthy individuals to reinforce a sense of values and ranges considered normal. Finally, the psychomotor skill involved with applying and securing the blood pressure cuff and attached sphygmomanometer, applying and holding the stethoscope diaphragm, pumping air into the bulb, releasing pressure from the cuff, and reading the meter while listening for the blood pressure sounds (called Korotkoff sounds) does take coordination and skill. Although the process is basic and consistent, practice reinforces efficient application in actual patient care situations.

Pulse Oximetry

In addition to the measurement of vital signs described, pulse oximetry is a tool used to provide instant information about a subject’s cardiopulmonary status. Specifically, the pulse oximeter is a noninvasive probe (in the form of a clip-on device placed on the ear, finger, foot, or nose) that provides a digital readout of oxyhemoglobin saturation. Most commonly, this device is used to identify hypoxemia, monitor the patient’s tolerance to activity, and to evaluate patient response to treatment.26 However, for the patient in the hospital setting who has coexisting cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal involvement, pulse oximetry is a viable tool for establishing goals to address tolerance to progressive activities.

The standard normal value for oxygen saturation ranges from 95% to 100%; this value is not expected to change with activity or exercise in the healthy individual.14 This level noticeably decreases in patients with chronic respiratory disease; the PTA must be aware of normal ranges for a given individual in this case. Activity should be halted if the value of oxygen saturation drops below 90% in the acutely ill patient or below 86% in the patient with chronic lung disease.16 If the referring physician has indicated any other specific level of oxygen saturation to use as a guideline for a given patient, the PTA must be sure to be aware of this level, so that exercise tolerance will not be exceeded. PTAs should also assess other vital signs, skin and nail bed color, tissue perfusion, mental status, breath sounds, and respiratory pattern in patients with whom they use pulse oximetry.14

Vital Signs and Exercise

Certain responses in vital signs are expected with exercise. In a “Scientific Statement” published by The American Heart Association,13 detailed guidelines for exercise testing and training are provided, taking into consideration the cardiovascular health status of the patient. Abnormal blood pressure responses include the absence of an increase in systolic pressure or a drop in systolic pressure with exercise; a normal response is an increase that correlates to the rate and intensity of exercise initiation.19 If the patient’s systolic blood pressure elevates to >250 mm Hg or if the diastolic pressure elevates to >110 mm Hg during exercise, the activity should be discontinued.14 Further, the systolic pressure should not rise >20 mm Hg with minimal to moderate exercise or >40 to 50 mm Hg with intensive exercise.14 Diastolic blood pressure is not expected to increase or decrease more than 10 mm Hg with exercise in the healthy adult.14 Refer to Box 2-3 for a summary of abnormal responses of vital signs to exercise.

Fatigue

In general, the PTA is expected to be competent in performing data collection techniques and selected interventions such that they can make appropriate modifications based on patient responses.2 In relation to fatigue, this may translate as observing and reporting abnormal responses to activity and making modifications to the interventions within the context of the PT’s plan of care. Fatigue may be specific to an individual muscle or muscle group, or it may affect the entire body, manifesting as cardiopulmonary (also called cardiorespiratory or general) fatigue.19 Frequently, associated symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations or headache are associated with cardiopulmonary fatigue.14

A muscle in a state of fatigue is unable to generate a normal contraction, which may manifest by decreased force, ROM, or quality of the contraction. The patient may complain of discomfort or cramping in the muscle being exercised.19 When a muscle is fatigued, the patient may compensate by consciously or subconsciously substituting with another muscle or muscle group that performs the same or similar action. For this reason, it is very important for the PTA to be particularly familiar with muscle actions and potential substitutions and observe patients during exercise activities. In terms of quality of motion, fatigue may result in tremulous or jerky motions, instead of a smooth contraction through the ROM.19

Generalized fatigue is apparent when the patient is experiencing dyspnea or inability to breathe normally with activity, indicating a decreased ability of the body to use oxygen efficiently.19 One tool that has been determined to be a fairly good indicator of a patient’s pulmonary tolerance to exercise is a standardized scale referred to as the Borg scale, or the Rate of Perceived Exertion scale (RPE).16 This instrument calls for the patient to place an objective grade on the amount of exertion he or she perceives with exertion, thus making a subjective report more measurable. A similar instrument, the Dyspnea Scale is used for rating the level of shortness of breath, or dyspnea.16 As with all standardized instruments, the PTA uses the form, instrument, or technique consistent with that of the supervising PT. If the PT chose to use a standardized instrument to document examination data related to the patient’s tolerance to activity, it is likely that a goal addressing that impairment is included in the plan of care, with the outcome to be measured using the same instrument.

ASSESSMENT OF MUSCULOSKELETAL STRUCTURES

End-Feel

End-feel is the term used to describe the barrier encountered that prevents further motion at the end of passive ROM in a joint. Because different types of tissue have different characteristics and qualities to their constituency, there are associated normal (physiologic) and abnormal (pathologic) end-feels for each tissue. Normal end-feels are described simply as soft, firm, or hard.25 Other terms used to denote normal end-feels include soft tissue approximation, such as occurs with knee flexion; muscular stretch, such as occurs with hip flexion with the knee straight; capsular stretch, as denoted in extension of metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers; ligamentous stretch, as found in forearm supination; or bone contacting bone, such as occurs with elbow extension.25 Obviously these terms are descriptive of the specific anatomic relationships of structures that normally limit the motion of each joint. The PTA student is encouraged to practice assessing the different normal end-feels on a variety of subjects, because the exact perception varies depending on the structure and build of each individual tested.

When one of the end-feels (described in the preceding) is noted in a joint that normally exhibits a different end-feel, it is considered to be abnormal or pathologic end-feel. Abnormal end-feels may be classified as soft, firm, hard, or empty. A soft end-feel occurs sooner or later in the ROM than is usual for a joint, or in a joint that normally has a firm or hard end-feel, and is described as feeling “boggy.” A firm end-feel occurs sooner or later in the ROM than is usual, or it may be noted in a joint that normally would have a soft or hard end-feel. Hard end-feels occur sooner or later in the ROM than is normal for a joint or in a joint that normally has a soft or firm end-feel, and a bony grating or bony block is noted. An empty end-feel is when no real end-feel is noted because pain prevents the examiner from reaching the end of ROM.25 Resistance is not noted with an empty end-feel other than the patient/client’s protective muscle splinting or spasm.25 As always, when the PTA recognizes these abnormal circumstances, these findings must be documented and reported to the evaluating PT.

Skeletal Muscle Tissue

Skeletal muscle tissue has various characteristics that allows it to function as it does. Three such characteristics are excitability, contractility, and extensibility. Excitability (or irritability) refers to the ability of skeletal muscle tissue to be stimulated; contractility is the ability of skeletal muscle tissue to contract or shorten; and extensibility is the ability of skeletal muscle to extend or stretch, and to return to its resting length after having contracted.32

Strength Testing

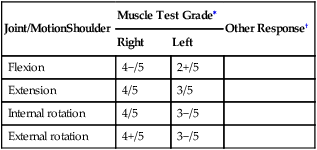

When the plan of care includes goals related to increase in specific muscle grades, the PTA must use the same technique for assessing the muscle strength as the evaluating PT used at the time of the initial examination and evaluation. In general, specific manual muscle testing takes into account the precise attachments, action, and position of a muscle during movements or isometric contractions against gravity. Scales for specific muscle grades are also precise, based on word/letter or number scales with strict definitions for each. A table is an organized and convenient way to record data relating to muscle strength testing; an example of a table format is provided in Table 2-4.

Table 2-4

Sample Format for Recording Muscle Strength

| Joint/MotionShoulder | Muscle Test Grade∗ | Other Response† | |

| Right | Left | ||

| Flexion | 4−/5 | 2+/5 | |

| Extension | 4/5 | 3/5 | |

| Internal rotation | 4/5 | 3−/5 | |

| External rotation | 4+/5 | 3−/5 | |

∗Measurements represent example of ascending 0 to 5 scale.

†“Other Responses” could include notation regarding the presence of pain, etc.

If the PTA observes signs of pain with resisted movements during strength testing, he or she must make certain that the test is being performed in such a way as to avoid causing active insufficiency of muscles being tested. Kendall and co-workers18 define active insufficiency as: “The inability of a Class III or IV two-joint (or multijoint) muscle to generate an effective force when placed in a fully shortened position.” Thus, active insufficiency can result from improper positioning of a two-joint or multijoint muscle and causes a cramping type of pain. Pain experienced with muscle testing during a properly performed technique could be indicative of an inflammatory state or strain of the tissues being stressed. Because the musculotendinous tissue is responsible for sustaining joint position during resistance, the presence of pain with muscle testing, even if the result indicates intact strength, points to involvement of the muscle or tendon. Once again, if these data represent a change from the initial examination or evaluation data, it should be documented and reported to the evaluating PT.

Tone refers to the resistance of muscle tissue to passive elongation or stretch and is determined through observation of movements for quality of motion and control of motion (including grading and coordination) and through palpation.26 True changes in muscle tone should also be noted in the context of patterns of involvement such as described in the preceding and should be differentiated from a local muscle guarding or splinting response.

Stretching and Palpation

In general, the stage of inflammation determines when pain is felt with movement. During the acute stage of inflammation, pain is usually encountered before tissue resistance; during the subacute stage, pain is usually synchronous with tissue resistance; and during the chronic stage, pain usually occurs after tissue resistance is encountered.26 An increase in complaints of pain with stretching is reported in the event that a previous stretching or strengthening exercise program has been performed too vigorously or aggressively.

Muscle tenderness or soreness to palpation is not by itself an accurate indicator of the tissues involved because referred pain can also manifest as tenderness. However, the PTA should note and document the location and degree of tenderness or soreness for purposes of comparison to initial examination findings and possibly as a measure of progress toward goals, if the supervising PT addressed this area in the plan of care. A previously unnoticed pattern of tenderness revealed while the PTA is working with the patient should also be documented and reported to the supervising PT because patterns of the distribution of tender points represent the hallmark characteristic of conditions such as fibromyalgia. It is also important to note that the core features of fibromyalgia syndrome include widespread pain lasting more than 3 months, and widespread local tender points that are described as painful upon palpation.14

Flexibility

The end-feel associated with a loss of muscle or tendon flexibility secondary to increased tension in a muscle is described as muscular end-feel, and muscle-spasm end-feel relates to when joint movement is stopped abruptly with some rebound due to muscles contracting reflexively to prevent further joint movement.15

Bones

Of primary importance to the physical therapy clinician is the need to rule out conditions or disease processes that are beyond the professional scope of physical therapy, warranting medical diagnosis and treatment. Even without the advent of direct access to physical therapy care, it is possible that a patient may be referred to physical therapy in error for treatment of a condition that in fact requires strict medical attention. The main consideration with bone tissue is fracture. The potential exists for the fracture to be missed on initial examination (medical or physical therapy). An existing fracture also may progress, in terms of malalignment, in the case of a hairline or crack fracture, in which case referral for immobilization may be indicated. Therefore it is critical for the PTA to have an understanding of the signs and symptoms of fracture, regardless of the severity. Common signs and symptoms include pain and local tenderness, deformity, edema, ecchymosis, and a loss of overall function and mobility.8

If the patient exhibits exquisite point tenderness over a localized site other than a ligament or other supportive structure, a fracture may be indicated versus other musculoskeletal involvement (e.g., a ligamentous sprain).14 The PTA should also be aware that fractures can occur as a result of relatively minor trauma, such as sneezing or lifting a sack of groceries out of the car. Often times this occurs in patients who have osteoporosis.8 Because of the high prevalence and risk of osteoporosis, the astute PTA must recognize the possibility of vertebral compression fractures in a patient with complaints of mid or low back pain. Though sudden impact fractures are the most common type of fracture, the PTA must also be aware of the possibility of stress and pathologic fractures. A stress fracture is a microscopic disruption or break in a bone that is not displaced and produces pain that is described as a localized tenderness or deep aching pain that increases with activity and improves with rest.14 Pathologic fractures occur in bones that are weakened by disease or tumors and frequently occur spontaneously with very little or no stress. They can be local to the cause, such as with infections, cysts, or tumors, or generalized, as in osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, or disseminated tumors.27

Joints and Ligaments

Accessory Joint Motions

As a component of evaluation, the PT assesses ligamentous integrity and accessory joint motions for the purposes of differential diagnosis and making decisions on which to base the plan of care. It is the position of the American Physical Therapy Association that spinal and peripheral joint mobilization techniques are interventions performed exclusively by the PT.6 Although the PTA is not responsible for these elements of physical therapy patient care, it is nonetheless important that he or she understands the implications of assessment procedures that may reveal problems with structures that contribute to joint integrity.

The term accessory joint motions refers to “motions between adjacent joint surfaces that occur when a bone moves through a range of motion; includes slides (glides), distractions, compressions, rolls, and spins.”26 Accessory joint motions are also described as motions that occur during active motion, but are not under voluntary control.19 Another term used to describe these motions is arthrokinematics. For the accessory motions of roll, slide, and spin to occur in a joint, there must be adequate capsule laxity.19 Roll occurs when one bone within a joint rolls on another bone within the joint. It always occurs in the same direction as bone motion, and new points on one bone meet new points on the other bone.19 The slide accessory motion relates to the concave-convex rule. If the surface of the moving bone segment is convex, sliding is in the direction opposite of the angular movement of the bone; and if the surface of the moving bone is concave, sliding is in the same direction as the angular movement of the bone.19 Spin takes place when there is rotation about a stationary axis, and a point on the moving surface creates an arc as it spins. Abnormal findings that may be noted in the presence of impaired accessory motions include decreased joint ROM, a capsular end-feel during stretching techniques, and substitution or compensatory attempts by the patient to obtain full motion.

Distraction and Compression

Bursae are fluid-filled sacs that are located near tendinous insertions to reduce friction with motion. Bursae also may develop as an adaptive mechanism in the presence of excessive friction. An inflamed bursa sometimes is visible near a joint as a small, soft, encapsulated protrusion that is tender to touch. With bursitis, movement of the nearby joint will be painful and/or motion may be restricted in a noncapsular pattern.15 Any signs of a pathologic or inflamed bursa should be documented and reported to the supervising PT. Changes in exercise programs or functional activities should be incorporated into the plan of care. If a patient presents with a lump under the skin, joint pain and swelling, fever, chills, malaise and redness, the patient may be exhibiting signs of gout and requires referral for further medical workup if this condition has not been diagnosed previously.14

Ligamentous Integrity

If the PTA notices the sudden onset of increased edema, heat to touch, and extremely painful and limited mobility during the course of treatment of a patient with a ligament sprain, the supervising PT must be consulted to seek medical referral to rule out hemarthrosis (bleeding inside the joint capsule).19

BALANCE

According to the Normative Model,2 the PTA is to be competent in performing balance, coordination, and agility training. Three physiologic systems linked to balance control include somatosensory (musculoskeletal and neuromuscular components), visual, and vestibular. The vestibular system involves the structures and organs of the inner ear, which play a key role in maintaining upright posture, equilibrium, and orientation, all components of balance. Although the application of interventions designed to correct vestibular problems is beyond the skill level of an entry-level PTA, he or she must be aware that patients who report symptoms of vertigo, dizziness, balance problems, coordination problems, trouble focusing or tracking objects, hearing loss, tinnitus, nausea, vomiting, motion sickness, ear pain, headaches, or a sensation of fullness in the ears may need further physical therapy or medical assessment to rule out or confirm involvement of vestibular conditions. (Detailed information about vestibular disorders can be found on the website of the Vestibular Disorders Association at www.vestibular.org.)

DOCUMENTATION

The Physical Therapist Assistant Clinical Performance Instrument5 lists the following sample entry-level behaviors associated with the criterion, “Produces documentation to support the delivery of physical therapy services”:

“Documents aspects of physical therapy care, including selected data collection measurements, interventions, response to interventions, and communicates with family and others involved in delivery of patient care.

“Documents aspects of physical therapy care, including selected data collection measurements, interventions, response to interventions, and communicates with family and others involved in delivery of patient care.

Produces documentation that follows guidelines and format required by the clinical setting and law.

Produces documentation that follows guidelines and format required by the clinical setting and law.

Documents patient care consistent with guidelines and requirements of regulatory agencies and third-party payers.

Documents patient care consistent with guidelines and requirements of regulatory agencies and third-party payers.

Produces documentation that is accurate, concise, timely, and legible.

Produces documentation that is accurate, concise, timely, and legible.

Demonstrates technically correct written communication skills.”5

Demonstrates technically correct written communication skills.”5

In the subjective section of the note, the PTA would document any patient reports related to functional status or disability. In the objective section of the SOAP note, the PTA would document treatment performed, including frequency, duration, and intensity; patient education; equipment provided; and changes in patient’s status including observed changes during or after treatment.29 In the plan section of the SOAP note the PTA would indicate the intervention(s) for the next patient visit, what the patient is to be doing between treatments, as well as steps that will be taken to reach the established goals.21 So how does assessment fit into the PTA’s documentation?

The assessment is the key portion of documentation that links subjective and objective data to the physical therapy goals, outcomes, and plan. Thus, in the assessment section of the note, “…the PTA summarizes the information in the S and O sections and reports the progress being made toward accomplishing the goals.”21

Box 2-4 provides a sample SOAP note, written with the intent of offering an example of an effectively documented assessment by a PTA.

Summary

GLOSSARY

Assessment “The measurement or quantification of a variable or the placement of a value on something.”4

Centralization The increase of signs and symptoms in the immediate area of the lesion.

Judgment “Decisions made within the clinical environment that are based on the established physical therapy plan of care. With consideration toward safety, a problem-solving process is applied that includes decision rules (e.g., codes, protocols), thinking, data collection, and interpretation.”5

Referred pain Pain that is “felt in an area far from the site of the lesion, but supplied by the same or adjacent neural segments.”14

Trigger points “Small, localized tender areas found within skeletal muscles, fascia, tendons, ligaments, periosteum, and pericapsular areas.”30

∗The following definition for the term judgments is offered in the glossary of the CPI: “Decisions made within the clinical environment that are based on the established physical therapy plan of care. With consideration toward safety, a problem-solving process is applied that includes decision rules (e.g., codes, protocols), thinking, data collection, and interpretation.”5

†Data collection skills are defined as “those processes/procedures used to gather information through observation, measurement, subjective, objective, and functional findings; progression toward goals; and interpretive processes/procedures applied to formulate a judgment/decision within the plan of care established by the physical therapist.” The definition also states that [data collection skills] “must be integrated to achieve the most effective interventions and optimal outcomes.”5