3. The role of outcomes and observational research in evaluating integrative medicine

William ‘Mac’ Beckner and William Harlan

Chapter contents

Introduction61

History and value of RCTs in the evaluation of medical interventions62

General principles of RCTs62

Issues and limitations related to RCTs63

Research in complementary and integrative medicine64

The role of outcomes research and observational studies in integrative medicine65

Measuring non-specific effects66

Incorporating outcomes integrative medicine and whole-systems research67

Capturing the impact of personalized integrative care in the era of genomic medicine68

Clear and rigorous reporting of observational studies68

Introduction

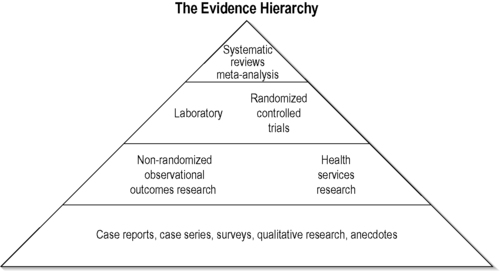

Methods that are used in conventional medical research are designed to produce a successive hierarchy of scientific inquiry that, in turn, produces improved and therefore more rigorous evidence upon which to make clinical decisions. Typically described in a structured hierarchy are clinical observations, case studies, retrospective and prospective case series, followed by cohort studies with historical and concomitant non-randomized controls. Open-label randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and blinded, placebo-controlled RCTs are listed at the top of the hierarchy. They offer the most internal validity and minimization of bias and are considered by many to be the most reliable evidence for evaluation of modern medical interventions. This hierarchical structure (Figure 3.1) is based on a pharmacological model designed to produce the most definitive evidence of efficacy and harms and lead to regulatory approval. This hierarchy tends to undervalue the important evidence developed from observational studies and the contributions such studies make to generalizablity, long-term evaluation of efficacy and harms and to hypothesis generation as well as explanation of mechanisms underlying response to interventions.The hierarchal approach reaches its limitations when one considers the complexities of clinical decision-making and the various types of evidence needed for an evidence-based approach that is relevant within the context of clincial practice.

|

| FIGURE 3.1

Adapted with permission from Jonas (2001).

|

History and value of RCTs in the evaluation of medical interventions

One can argue that the first clinical trial dates back to approximately 600 bc when Daniel of Judah conducted what is probably the earliest recorded clinical trial (Book of Daniel). He compared the health effects of the vegetarian diet with those of a royal Babylonian diet over a 10-day period. It was a short and simple comparison of the health effects of the vegetarian diet with the royal Babylonian diet. The trial had obvious deficiencies by contemporary medical standards (10-day duration, allocation bias, ascertainment bias and confounding by divine intervention), but the report has remained influential for more than two millennia (Jadad 1998).

Credit for the modern randomized trial is usually given to Sir Austin Bradford Hill (1952). The Medical Research Council trials on streptomycin for pulmonary tuberculosis are rightly regarded as a landmark that ushered in a new era of medicine. Since Hill’s pioneering achievement, the methodology of the RCT has been increasingly accepted and the number of reported RCTs has grown exponentially. The Cochrane Library now lists approximately 550 000 such trials, and they provide the basis for meta-analysis and contribute to what is currently called ‘evidence-based medicine’ (Cochrane Collaboration 2008).

General principles of RCTs

The RCT is one of the most powerful tools of research, simple in concept but complex in execution. In essence, the RCT is a study in which treatments are allocated at random so participants receive one of several clinical interventions (Jadad 1998). Usually, the term ‘intervention’ refers to medical treatment, but it should be used in a much wider sense to include any clinical intervention that may have an effect on health status. Such clinical interventions include prevention strategies, screening programmes, diagnostic tests, behavioural and educational approaches, complementary and alternative medicine approaches, surgical and manipulative procedures, and devices, as well as the type or setting for provision of health services (Jadad 1998).

RCTs are powerful tools for conducting research, mainly because randomizing patients to receive or not receive the intervention balances the comparison groups with respect to factors influencing the outcomes. Thus, any significant differences between groups in the outcome event can be attributed to the intervention and not to some other identified or unidentified factor.

Issues and limitations related to RCTs

Randomized trials are designed to provide unbiased answers to specific hypotheses and theories regarding efficacy and harms of interventions on a well-defined and measured clinical outcome. Despite the strong internal validity that is designed into the trial there are important limitations. Trials are expensive to conduct and the results are very specific to the questions addressed and the populations in which they are conducted and their generalizability is often limited, particularly in pharmaceutical trials. Further, the populations selected for RCTs are based on the minimum number estimated to provide a statistically reliable result and the study groups are relatively homogeneous and limited in severity of disease and comorbidities. Duration of follow-up is usually constrained, as is populational diversity. These limit the ability to extrapolate the findings to the ‘real’ groups found in the usual practice setting. Further, limited comparisons are made between competing therapeutic approaches, thus leaving larger questions of comparative effectiveness unanswered. The result can be a limited application to the therapeutics of both traditional and integrated practices.

An excellent example of the issues that can arise with RCTs can be seen in the publications on mammography screening. The most important references concern the article by Miettinen et al., 2002 and Larsson et al., 1997 linking screening for breast cancer with mammography and an apparently substantial reduction in fatalities and the responses that it elicited (Silverman and Altman, 1996 and Tabar et al., 2001). While the strongest conclusions and inferences can be reached when there is concordance between research using different methods (e.g. RCT and prospective cohort methods), such agreement is not always found, such as the different conclusions reached by cohort versus RCT studies of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women (Chlebowski et al., 2003 and Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2003), antioxidant supplements to prevent cancer (Bardia et al. 2008) or decreased risk of dementia/cancer in patients using statins (Shepherd et al. 2002).

Additionally, RCTs may not be the most appropriate tool for the assessment of interventions that have rare outcomes or outcomes that take a long time to develop. In such instances, other study designs, such as case-control studies or cohort studies, may be more appropriate. In other cases, RCTs may not be feasible because of financial constraints or because of the expectation of low compliance or high drop-out rates.

Integrative medicine (IM) poses additional challenges to the RCT model. It may involve complex models of disease causation that are often treated with complex interventions that involve both specific and non-specific treatment effects (Jonas et al. 2006). Further, many of these interventions are non-pharmacologic in nature and do not lend themselves to testing of a single treatment element. There are challenges in finding credible control interventions and blinding procedures for a multifactorial ‘systems’ approach rather than a simple treatment regimen. Further, there is increasing pressure that research in IM provides results that are meaningful in real-life clinical practice (Boon et al. 2007). In such cases, the use of large prospective cohort studies can often afford a broader and longer-term assessment of several treatment exposures and clinical outcomes. However, the findings may be biased by selection of therapies for patients which are made based on physician or patient preferences. When treatment effects are quantitatively small or moderate the biased selection of therapies may blur or distort the true differences.

Research in complementary and integrative medicine

The research base for IM interventions has increased dramatically in recent years (Vickers 2000), yet there is not a critical mass of research evidence about IM and the effect of these approaches on health care to inform policy-makers and consumers adequately and uniformly on the effectiveness of these interventions. One challenge for research is how to determine the therapeutic effectiveness of interventions and thus this concerns the definition of ‘effectiveness’. Another challenge is that interventions in IM are often multifaceted with complex unknown interactions among the components. Therapies delivered as a multifactorial ‘system’ rather than simple treatment regimen present challenges to design studies that are rigorous yet provide results that are meaningful in real-life clinical practice.

Challenges are further compounded by clinician–patient interactions; patient goals and priorities; the effects of meaning and context; patient self-care; environmental factors and social policies affecting health quality; and system factors affecting availability of resources that promote health, health behaviours or health care. Research should also focus on patient-centred care in the context of family, culture and community. Many clinical trials in the field of IM have used RCT methodologies, evaluating single components from a wider system of care in treating a specific medical condition (e.g. St John’s wort for depression, a specific set of acupuncture points for headaches, a protocol of chiropractic adjustments for low-back pain or melatonin for insomnia).

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to provide a summary of all the clinical trials conducted in the field, but a recent search of PubMed found nearly 6500 RCTs under the medical subject heading of complementary therapies. In some cases, there have been enough studies on a particular treatment and condition to result in a systematic review or meta-analysis. Nearly 3000 systematic reviews and 400 meta-analyses are found in Medline when using the complementary therapies subject heading. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews had published 384 systematic reviews related to complementary therapies as of December 2009. Summaries of those reviews have been published (He et al., 2007, Bausewein et al., 2008, Bjelakovic et al., 2008, Dickinson et al., 2008, Horneber et al., 2008, Maratos et al., 2008, Priebe et al., 2008 and Zhu et al., 2008).

The role of outcomes research and observational studies in integrative medicine

In conventional medicine, observational studies have provided important insights regarding the role of exposures to clinical outcomes: smoking, radiation, hormone levels and high-meat diets in the development of different kinds of cancer, lipids and coronary disease, hypertension and stroke, and sleeping position and sudden infant death syndrome (Rothwell & Bhatia 2007). Traditional biomedical research focuses on one particular disease outcome, but integrative care often addresses multiple health concerns within a single individual. These issues call for innovative research models to address the challenges inherent in testing simultaneous treatments for multiple health concerns. For example, in the case of many chronic conditions such as rheumatological diseases, chronic pain and chronic bowel diseases, IM interventions are often sought as a last resort. In such cases, an argument can be made that the study of outcomes of an effective treatment collected in large enough numbers and with methodologic rigour can be of more value than an RCT, regardless of whether the effects are due to specific or non-specific treatment effects.

An example of the value of observational research combined with an RCT in complementary and integrative medicine can be seen in recent German studies involving acupuncture and pain. A systematic review of randomized trials in patients suffering from osteoarthritis of the knee considered the available evidence as promising, but further, rigorous trials were considered necessary. In the study the Program for the Evaluation of Patient Care with Acupuncture (PEP-Ac) used a combined approach of both randomized trials and a large-scale observational study (Melchart et al. 2004). The large-scale observational study of osteoarthritis, which included 736 patients, showed that patients experience clinically relevant improvement after a treatment cycle with acupuncture. Side-effects were infrequent and minor, and the amount of pain medication consumed by patients decreased considerably (Linde et al. 2005).

In parallel with this study, the authors conducted an RCT comparing acupuncture with minimal acupuncture (superficial needling of non-acupuncture points) and a wait list control in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee (Witt et al. 2005). In this trial, therapeutically adequate acupuncture was significantly superior to both minimal acupuncture and waiting list control after 8 weeks. After 6 and 12 months, differences between acupuncture and minimal acupuncture were no longer significant. Absolute improvement in the Western Ontario and McMaster universities (WOMAC) index was slightly higher than that observed in the observational study and changes for the pain disability index and physical health were very similar in the two studies. Additionally, results were in accordance with the promising results from a review of randomized trials on acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee (Ezzo et al. 2000) as well the large randomized trial by Berman et al. (2004). Overall, the available evidence from both observational studies and RCTs suggests that acupuncture is effective in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. However, a relevant part of the effect might be due to unspecific needling effects or placebo effects which favour continued investigations of complementary and integrative medicine with large multisite observational studies.

Measuring non-specific effects

In a clinical trial, patients improve for multiple reasons. These include regression to the mean of repeated measurements, spontaneous remission, natural course, biased reporting, non-specific therapeutic effects and specific therapeutic effects. These effects are often generally referred to as the ‘placebo effect’ and they can account for improvements in up to 60% of patients for some conditions (Kaptchuk et al. 2008). Historically, placebo effects have been considered more a nuisance than a useful therapeutic effect because of the need to control such effects within the context of placebo-controlled trials for pharmacologic treatments. Further, the efficacy observed in the placebo arm may sometimes be significantly superior to no treatment or standard medical care (Linde et al., 2005, Melchart et al., 2005, Brinkhaus et al., 2007 and Haake et al., 2007). The interaction and context of an integrative encounter are likely to increase this non-specific effect. Instead of considering the placebo effect as of secondary importance, it might be more apt to consider the placebo effect as ‘contextual healing’, an aspect of healing that has been produced, activated or enhanced by the context of the clinical encounter(35) that maximizes contextual healing, including the environment of the clinical setting, cognitive and affective communication of practitioners and the ritual of administering the treatment (Kaptchuk et al. 2002).

A core aspect of IM is the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient (Chang et al., 1983 and Quinn et al., 2003) that has been incorporated into the evolving concept of ‘relationship-centred care’ (Deng 2008). Relationship-centred care focuses on the importance of human relationships, with experience of the patient being at the centre of care. Additionally, a more integrative approach towards patient care entails incorporating biopsychosocial interdisciplinary content emphasizing compassion, communication, mindfulness, respect and social responsibility. Studies measuring the clinical impact of the relationship between practitioner and patient and outcomes of the training of clinician healers (Novack et al., 1999 and Miller et al., 2003) are ripe areas for future outcomes research in IM. Enhancing research efforts towards harnessing the non-specific therapeutic effect rather than controlling for it is likely to offer expanded tools and additional insight into patient care. In situations where it is important to separate the specific effect from ‘contextual healing’, optimal effort needs to be placed towards validating a placebo control before pursuing large multicentre RCTs.

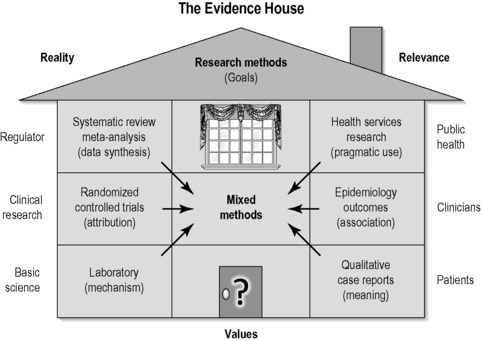

With the complexities involved in conducting research in IM, Jonas (2001) argues that perhaps the best model of evidence is one that balances both reality and relevance in the evaluation of complex interventions such as physiotherapy, surgery and integrative practices (Figure 3.2). There is an essential tension between internal validity (rigour and the removal of bias) and external validity (generalizability) in the hierarchical model and this weakness, Jonas argues, warrants a multiplicity of methods, using different designs, counterbalancing their individual strengths and weaknesses to arrive at pragmatic but equally rigorous evidence. The ‘evidence house’(Jonas 2001) (Figure 3.2) seeks to lateralize the main knowledge domains in science in order to highlight their purposes by aligning methodologies that isolate specific effects (those with high internal validity potential) and those that seek to explore utility of practices in real clinical settings (those with high external validity potential).

|

| FIGURE 3.2

Adapted with permission from Jonas (2001).

|

Incorporating outcomes integrative medicine and whole-systems research

Researchers can make use of outcome measurement tools developed in conventional disciplines of medicine, especially those emphasizing functional performance in addition to structural integrity and those taking into consideration the psychological and societal impact of disease (Coons et al. 2000). Such outcomes have been collected in rheumatology (Ward 2004), neurology (von Steinbuechel et al., 2005 and Miller and Kinkel, 2008), geriatric (Burns et al., 2000 and Demers and McKelvie, 2000), rehabilitation (Andresen and Meyers, 2000 and Donnelly and Carswell, 2002) and pain and palliative care (Turk et al. 2002). They form a foundation from which IM researchers can build a truly global outcome measurement system. Another consideration in IM research is how to evaluate multimodality health care approaches.

There is an impetus for ‘whole-systems’ research, which strives to examine the effect of a multimodality health care approach to provide individualized treatment. The belief is that this will more accurately evaluate the health care currently being provided to patients and is an increasingly frequent trend in IM research. There are several articles in the literature urging IM researchers to consider research methods beyond the RCT (Cardini et al., 2006, Boon et al., 2007 and Fonnebo et al., 2007). One example of whole-systems research is the study by Ritenbaugh et al. (2008), who examined the effect of whole-system traditional Chinese medicine versus naturopathic medicine versus standard of care for the treatment of tempromandibular disorders. In this study, improvement was seen in temporomandibular disorders when participants were randomized to whole-systems treatment interventions beyond that seen in the standard care group. Several investigators have discussed the need to use more complex methods of analysis so that these systems of health care can be examined, rather than the efficacy of each part of the system (Ritenbaugh et al., 2003, Verhoef et al., 2005 and Bell and Koithan, 2006). One way to capture these outcomes is to develop clinical research networks and complex system analysis tools to assess whole-systems research. However, it is critical to engage skilled bioinformatics and biostatistical expertise for modelling and analysis as these more complex studies require new statistical approaches (Bell & Koithan 2006). Researchers should be encouraged to add qualitative measures to studies because they can provide a source of data for unexpected outcomes and a way to measure the broader effects of a whole system, such as IM (Verhoef et al. 2005). As these new study designs mature it will be important for IM researchers to consider the range of effects IM treatments may have for patients, and thus to measure a broad area of outcomes in order to detect these effects.

Capturing the impact of personalized integrative care in the era of genomic medicine

Personalized medicine is just beginning on a long journey of discovery that will include genomics and genetic influences on conditions and their development (and response to environmental exposures) and the individual response to treatments. Genomics refers to the study of all the genes of a cell, or tissue, at the DNA (genome), mRNA (transcriptome) or protein (proteome) levels. It is well known that individuals respond differently to risk exposure and interventions. Proposing a research agenda for incorporating genomic medicine into IM is described in Chapter 4. As new and innovative tools and technologies for genomic discovery become available they can be utilized to advance current knowledge of processes of healing and repair that fit into observational research approaches. A discovery model for genomic associations in IM could mirror what Weston & Hood (2004) call P4 medicine – predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory. In such a model health care interventions, both conventional and integrative care, would no longer be conceptualized in terms of disease, but rather in terms of mediating health and wellness.

Clear and rigorous reporting of observational studies

For outcomes research to be of value to health care decision-making it should be reported transparently so that readers can follow what was planned, what was done, what was found and what conclusions were drawn. The credibility of research depends on a critical assessment by peers of the strengths and weaknesses in study design, conduct and analysis. An analysis of epidemiological studies published in general medical and specialist journals found that the rationale behind the choice of potential confounding variables was often not reported (Pocock et al. 2004). Only a few reports of case-control studies in psychiatry explained the methods used to identify cases and controls (Lee et al. 2007). In a survey of longitudinal studies in stroke research, 17 of 49 articles (35%) did not specify the eligibility criteria (Tooth et al. 2005). Others have argued that without sufficient clarity of reporting, the benefits of research might be achieved more slowly (Bogardus et al. 1999) and that there is a need for guidance in reporting observational studies. Transparent reporting is also needed to judge whether and how results can be included in systematic reviews (Juni et al. 2001). However, in published observational research important information is often missing or unclear. Recommendations on the reporting of research can improve reporting quality. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement was developed in 1996 and revised 5 years later (Moher et al. 2001). Many medical journals support this initiative and require the reporting format of CONSORT, which has helped to improve the quality of reports of randomized trials (Egger et al., 2001 and Plint et al., 2006). Similar initiatives have followed for the reporting of meta-analyses of randomized trials (Moher et al. 1999) and diagnostic studies (Bossuyt et al. 2003).

Recently, researchers have established a network of methodologists, researchers and journal editors to develop recommendations for the reporting of observational research: the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. The STROBE statement was designed to help researchers when writing up analytical observational studies, support editors and reviewers who are considering such articles for publication and help readers when critically appraising published articles. Adopting the STROBE checklist for research in IM observational studies can serve a wide range of purposes, on a continuum from the discovery of new findings to the confirmation or refutation of previous findings (Vandenbroucke 2004). While some studies may be essentially exploratory and raise interesting hypotheses, others may pursue clearly defined hypotheses in available data.

The ultimate goal of outcomes research is to guide clinical practice and its efficient utilization to maximize benefits and to minimize patient harms. When formulating clinical guidelines, two factors are in play: strength of evidence and burden/risk to the patient. Because it is not always possible to have definitive evidence on safety and effectiveness and clinical decisions have to be made with limited information (Deng 2008), burden and risk to the patient need to be taken into account. Although the highest level of evidence is desirable for every health intervention, it is simply not possible to achieve this goal. Limited research resources have to be allocated according to priorities. Therefore, interventions or therapies having high risk or burden (economic/time/effort) to patients and society should meet a higher standard in strength of evidence, often in the form of multiple RCTs, to be utilized for regulatory or reimbursement approval and in clinical practice. Those with low or little risk/burden can be incorporated into practice even when the highest level of evidence is not available (McCrory et al. 2007). Implicit in this understanding is the notion that both the clinician and patient understand and agree with respect to: the problem; the goal of therapy; the evidence regarding safety and effectiveness of the therapy being considered; the extent to which it is accessible, affordable and of high and consistent quality; and availability of similar information about integrative treatments (or a combination of treatments) under consideration.

Using a combined strategy that utilizes both observational and outcomes research and RCTs enables methods to be modified so that the concerns of all stakeholders are taken into account. This ensures that as far as possible what is being assessed under experimental conditions is consistent with everyday IM practice. Unless evidence is generated in a way that satisfies such criteria, it is unlikely to have an impact.

References

Andresen, E.M.; Meyers, A.R., Health-related quality of life outcomes measures, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 81 (12 Suppl. 2) (2000) S30–S45.

Bardia, A.; Tleyjeh, I.M.; Cerhan, J.R.; et al., Efficacy of antioxidant supplementation in reducing primary cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis, Mayo Clin. Proc. 83 (1) (2008) 23–34.

Bausewein, C.; Booth, S.; Gysels, M.; et al., Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2) (2008); CD005623.

Bell, I.R.; Koithan, M., Models for the study of whole systems, Integr. Cancer Ther. 5 (4) (2006) 293–307.

Berman, B.M.; Lao, L.; Langenberg, P.; et al., Effectiveness of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial, Ann. Intern. Med. 141 (12) (2004) 901–910.

Bjelakovic, G.; Nikolova, D.; Gluud, L.L.; et al., Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2) (2008); CD007176.

Bogardus Jr., S.T.; Concato, J.; Feinstein, A.R., Clinical epidemiological quality in molecular genetic research: the need for methodological standards, JAMA 281 (20) (1999) 1919–1926.

Boon, H.; Macpherson, H.; Fleishman, S.; et al., Evaluating complex healthcare systems: a critique of four approaches, Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 4 (3) (2007) 279–285.

Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; et al., Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD Initiative, Ann. Intern. Med. 138 (1) (2003) 40–44.

Brinkhaus, B.; Witt, C.M.; Jena, S.; et al., Physician and treatment characteristics in a randomised multicentre trial of acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, Complement. Ther. Med. 15 (3) (2007) 180–189.

Burns, R.; Nichols, L.O.; Martindale-Adams, J.; et al., Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 48 (1) (2000) 8–13.

Cardini, F.; Wade, C.; Regalia, A.L.; et al., Clinical research in traditional medicine: priorities and methods, Complement. Ther. Med. 14 (4) (2006) 282–287.

Chang, J.D.; Eidson, C.S.; Dykstra, M.J.; et al., Vaccination against Marek’s disease and infectious bursal disease. I. Development of a bivalent live vaccine by co-cultivating turkey herpesvirus and infectious bursal disease vaccine viruses in chicken embryo fibroblast monolayers, Poult. Sci. 62 (12) (1983) 2326–2335.

Chlebowski, R.T.; Hendrix, S.L.; Langer, R.D.; et al., Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial, JAMA 289 (24) (2003) 3243–3253.

Collaboration, C., The Cochrane Library. (2009) ; Update Software [cited 2009 December 10]; Available from:www.update-software.com/cochrane.

Coons, S.J.; Rao, S.; Keininger, D.L.; et al., A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments, Pharmacoeconomics 17 (1) (2000) 13–35.

Daniel

Demers, C.; McKelvie, R.S., Exercise training for patients with chronic heart failure reduced mortality and cardiac events and improved quality of life, West. J. Med. 172 (1) (2000) 28.

Deng, G., Integrative Cancer Care in a US Academic Cancer Centre: The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Experience, Curr. Oncol. 15 (Suppl. 2) (2008); s108 es68–71.

Dickinson, H.O.; Campbell, F.; Beyer, F.R.; et al., Relaxation therapies for the management of primary hypertension in adults, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1) (2008); CD004935.

Donnelly, C.; Carswell, A., Individualized outcome measures: a review of the literature, Can. J. Occup. Ther. 69 (2) (2002) 84–94.

Egger, M.; Juni, P.; Bartlett, C., Value of flow diagrams in reports of randomized controlled trials, JAMA 285 (15) (2001) 1996–1999.

Ezzo, J.; Berman, B.; Hadhazy, V.A.; et al., Is acupuncture effective for the treatment of chronic pain? A systematic review, Pain 86 (3) (2000) 217–225.

Fonnebo, V.; Grimsgaard, S.; Walach, H.; et al., Researching complementary and alternative treatments – the gatekeepers are not at home, BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 7 (2007) 7.

Haake, M.; Muller, H.H.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; et al., German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups, Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (17) (2007) 1892–1898.

He, J.L.; Xiang, Y.T.; Li, W.B.; et al., Hemoperfusion in the treatment of acute clozapine intoxication in China, J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27 (6) (2007) 667–671.

Hill, A., The clinical trial, N. Engl. J. Med. (247) (1952) 113–119.

Horneber, M.A.; Bueschel, G.; Huber, R.; et al., Mistletoe therapy in oncology, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2) (2008); CD003297.

In: (Editor: Jadad, A.) Randomised controlled trials: a user’s guide: London (1998) BMJ Books, England.

Jonas, W.B., The evidence house: how to build an inclusive base for complementary medicine, West. J. Med. 175 (2) (2001) 79–80.

Jonas, W.B.; Beckner, W.; Coulter, I., Proposal for an integrated evaluation model for the study of whole systems health care in cancer, Integr. Cancer. Ther. 5 (4) (2006) 315–319.

Juni, P.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M., Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials, BMJ 323 (7303) (2001) 42–46.

Kaptchuk, T.; Eisenberg, D.; Komaroff, A., Pondering the placebo effect, Newsweek 140 (23) (2002) 71; 3.

Kaptchuk, T.J.; Kelley, J.M.; Deykin, A.; et al., Do ‘placebo responders’ exist?Contemp. Clin. Trials 29 (4) (2008) 587–595.

Larsson, L.G.; Andersson, I.; Bjurstam, N.; et al., Updated overview of the Swedish Randomized Trials on Breast Cancer Screening with Mammography: age group 40–49 at randomization, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. (22) (1997) 57–61.

Lee, W.; Bindman, J.; Ford, T.; et al., Bias in psychiatric case-control studies: literature survey, Br. J. Psychiatry 190 (2007) 204–209.

Linde, K.; Streng, A.; Jurgens, S.; et al., Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial, JAMA 293 (17) (2005) 2118–2125.

Maratos, A.S.; Gold, C.; Wang, X.; et al., Music therapy for depression, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1) (2008); CD004517.

McCrory, D.C.; Lewis, S.Z.; Heitzer, J.; et al., Methodology for lung cancer evidence review and guideline development: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, 2nd edition, Chest 132 (Suppl. 3) (2007) 23S–28S.

Melchart, D.; Hager, S.; Hager, U.; et al., Treatment of patients with chronic headaches in a hospital for traditional Chinese medicine in Germany. A randomised, waiting list controlled trial, Complement. Ther. Med. 12 (2–3) (2004) 71–78.

Melchart, D.; Streng, A.; Hoppe, A.; et al., The acupuncture randomised trial (ART) for tension-type headache – details of the treatment, Acupunct. Med. 23 (4) (2005) 157–165.

Miettinen, O.S.; Henschke, C.I.; Pasmantier, M.W.; et al., Mammographic screening: no reliable supporting evidence?Lancet 359 (9304) (2002) 404–405.

Miller, W.L.; Crabtree, B.F.; Duffy, M.B.; et al., Research guidelines for assessing the impact of healing relationships in clinical medicine, Altern. Ther. Health Med. 9 (Suppl. 3) (2003) A80–A95.

Miller, D.M.; Kinkel, R.P., Health-related quality of life assessment in multiple sclerosis, Rev. Neurol. Dis. Spring; 5 (2) (2008) 56–64.

Moher, D.; Cook, D.J.; Eastwood, S.; et al., Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses, Lancet 354 (9193) (1999) 1896–1900.

Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G., The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials, Lancet 357 (9263) (2001) 1191–1194.

Novack, D.H.; Epstein, R.M.; Paulsen, R.H., Toward creating physician-healers: fostering medical students’ self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being, Acad. Med. 74 (5) (1999) 516–520.

Plint, A.C.; Moher, D.; Morrison, A.; et al., Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review, Med. J. Aust. 185 (5) (2006) 263–267.

Pocock, S.J.; Collier, T.J.; Dandreo, K.J.; et al., Issues in the reporting of epidemiological studies: a survey of recent practice, BMJ 329 (7471) (2004) 883.

Priebe, M.G.; van Binsbergen, J.J.; de Vos, R.; et al., Whole grain foods for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1) (2008); CD006061.

Quinn, J.F.; Smith, M.; Ritenbaugh, C.; et al., Research guidelines for assessing the impact of the healing relationship in clinical nursing, Altern. Ther. Health Med. 9 (Suppl. 3) (2003) A65–A79.

Ritenbaugh, C.; Hammerschlag, R.; Calabrese, C.; et al., A pilot whole systems clinical trial of traditional Chinese medicine and naturopathic medicine for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders, J. Altern. Complement. Med. 14 (5) (2008) 475–487.

Ritenbaugh, C.; Verhoef, M.; Fleishman, S.; et al., Whole systems research: a discipline for studying complementary and alternative medicine, Altern. Ther. Health. Med. 9 (4) (2003) 32–36.

Rothwell, P.M.; Bhatia, M., Reporting of observational studies, BMJ 335 (7624) (2007) 783–784.

Shepherd, C.E.; McCann, H.; Thiel, E.; et al., Neurofilament-immunoreactive neurons in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, Neurobiol. Dis. 9 (2) (2002) 249–257.

Silverman, W.A.; Altman, D.G., Patients’ preferences and randomised trials, Lancet 347 (8995) (1996) 171–174.

Tabar, L.; Vitak, B.; Chen, H.H.; et al., Beyond randomized controlled trials: organized mammographic screening substantially reduces breast carcinoma mortality, Cancer 91 (9) (2001) 1724–1731.

Tooth, L.; Ware, R.; Bain, C.; et al., Quality of reporting of observational longitudinal research, Am. J. Epidemiol. 161 (3) (2005) 280–288.

Turk, D.C.; Monarch, E.S.; Williams, A.D., Cancer patients in pain: considerations for assessing the whole person, Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 16 (3) (2002) 511–525.

Vandenbroucke, J.P., When are observational studies as credible as randomised trials?Lancet 363 (9422) (2004) 1728–1731.

Verhoef, M.J.; Lewith, G.; Ritenbaugh, C.; et al., Complementary and alternative medicine whole systems research: beyond identification of inadequacies of the RCT, Complement. Ther. Med. 13 (3) (2005) 206–212.

Vickers, A., Recent advances: complementary medicine, BMJ 321 (7262) (2000) 683–686.

von Steinbuechel, N.; Richter, S.; Morawetz, C.; et al., Assessment of subjective health and health-related quality of life in persons with acquired or degenerative brain injury, Curr. Opin. Neurol. 18 (6) (2005) 681–691.

Ward, M.M., Rheumatology care, patient expectations, and the limits of time, Arthritis Rheum. 51 (3) (2004) 307–308.

Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Hendrix, S.L.; Limacher, M.; et al., Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative: a randomized trial, JAMA 289 (20) (2003) 2673–2684.

Weston, A.D.; Hood, L., Systems biology, proteomics, and the future of health care: toward predictive, preventative, and personalized medicine, J. Proteome Res. 3 (2) (2004) 179–196.

Witt, C.; Brinkhaus, B.; Jena, S.; et al., Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised trial, Lancet 366 (9480) (2005) 136–143.

Zhu, X.; Proctor, M.; Bensoussan, A.; et al., Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhoea, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2) (2008); CD005288.