The role of adjuvant radiotherapy in the management of breast cancer

Advances in radiotherapy planning and delivery

Three-dimensional CT planning has improved dose homogeneity both within the breast and/or to regional nodal areas while reducing dosage to critical normal tissues, particularly the lungs, heart and brachial plexus. In addition, breathing-adapted gating techniques have reduced cardiac irradiation.1

Achieving a homogeneous dose distribution is challenging in the breast because its contour changes in both cranio-caudal and sagittal planes. Homogeneity is poorer in the upper and lower regions of the breast, resulting in ‘hot spots’ in areas of the breast distant from the central axis.2 Tangential beam plans can be optimised to ensure that the volumes of the breast exceeding 105% of the prescribed dose are minimised. With IMRT the X-ray beam is dynamically collimated to modify its fluence, allowing a therapeutic dose to be ‘painted’ to the breast/chest wall and peripheral lymphatics while minimising dosage to critical adjacent structures. The ‘field-in-field’ technique (the addition of supplementary photon fields) reduces ‘hot spots’ such as the inframammary fold and the thin breast tissue close to the nipple–areola complex.2,3

The role of adjuvant radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

In principle, DCIS should be as sensitive as invasive breast cancer (IBC) to irradiation. However, its role in the conservative management of DCIS is less firmly established than for IBC and use of adjuvant RT varies across the UK with no clear standard of care.5

All these trials used a dose fractionation schedule of 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks. The EORTC trial6 randomised 1010 women with clinically or mammographically detected DCIS ≤ 5 cm in size to wide local excision alone or wide local excision plus whole breast irradiation (50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks). The 10-year local relapse-free rate was 85% with RT compared to 74% with surgery alone (hazard ratio (HR) 0.53, P < 0.001). In situ local recurrence rates were 7% and 13% respectively and invasive rates were also 7% and 13%. In the NSABP B-17 trial7 818 patients were randomised to +/− whole-breast radiotherapy (WBRT) after lumpectomy. RT reduced the local relapse rate from 16.8% to 7.7% (relative risk (RR) 0.38, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25–0.59; P < 0.00001). In a recent update of the trial with 10-year follow-up, invasive recurrence within the ipsilateral breast was associated with a slightly higher risk of death. In contrast, recurrence of DCIS was not.8 The UK/ANZ trial9 recruited 1701 patients treated by BCS. Patients were randomised into four treatment groups (BCS alone, BCS + RT, BCS + tamoxifen and BCS + RT + tamoxifen). Approximately 90% of patients were ≥ 50 years and screen detected. Median follow-up was 53 months. Local recurrence rates were 22%, 8%, 18% and 6% respectively. Adjuvant RT was associated with a significant reduction for both DCIS and IBC ipsilateral recurrence (HR 0.38, P < 0.0001). Radiotherapy reduced the risk of recurrence by 64% for DCIS (P = 0.0004) and by 55% for invasive year cancer (P = 0.01). The Swedish DCIS trial (SweDCIS)10 randomised 1067 patients after wide excision for DCIS to WBRT or no WBRT. There was a risk reduction of 16% in ipsilateral events (in situ or invasive carcinoma) at 10 years from RT (95% CI 10.3–21.6%) and a relative risk of 0.40 (95% CI, 0.30–0.54%). The effect of RT in women was lower in women younger than 50, but there was a substantial benefit in women > 60 years. Results of the four trials were pooled in a Cochrane review11 and showed that the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence was halved by radiotherapy at 10 years (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.32–0.76) with about 50% of the ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence (IBTR) being invasive and 50% DCIS. In a subgroup analysis according to age (</> 50 years, presence or absence of comedo necrosis and tumour size >/< 10 mm) all subgroups derived benefit from RT. Women > 50 years appeared to experience a greater reduction in recurrence than compared to younger women (HR 0.35 (> 50) vs. 0.67 (< 50)). What limits interpretation, as others have pointed out,5 is that none of the trials were designed prospectively for subgroup analyses. In addition, there have been criticisms of the quality of the DCIS trials, summarised in a review,13 and problems with these trials include deficiencies in radiological–pathological correlation, measurement of tumour size,14 routine imaging of pathology specimens, postoperative imaging, definition and classification of lesions,7 definition of tumour-free margins,15 consistency in inclusion/exclusion criteria, randomisation procedures and insufficient statistical power to detect small differences in survival.12 Attempts have been made to define a subset of patients from whom postoperative radiotherapy might be omitted. In the E5194 non-randomised study of wide local excision alone in 711 patients with low – or intermediate-grade DCIS ≤ 2.5 cm or high-grade ≤ 1 cm with margins ≥ 3 mm with median follow-up of 6.7 years, the 5-year ipsilateral recurrence rate was 6.1%.16 A continued increase in the rate of IBTR beyond 5 years is of concern and long-term follow-up will be needed to determine if omission of radiotherapy is safe.

The absolute benefits of radiotherapy on local control are greater in high-grade compared to low-grade DCIS. The thresholds for recommending radiotherapy vary widely internationally. In some centres radiotherapy is confined to patients with high-grade DCIS, whereas other women with all grades of DCIS are treated following BCS on the basis17 that there is no group that does not benefit. One of the arguments for a more conservative approach to selection is that these patients are subject to the same risks of radiation-induced morbidity (including cardiac damage, rib fractures and pneumonitis) as patients with invasive breast cancer. In some groups of women with DCIS mortality rates are < 1% and so this encourages a more cautious approach in recommending adjuvant breast irradiation. That said, the risks, for example, of cardiopulmonary morbidity have been substantially reduced by the use of three-dimensional CT planning.

Is there a role for a boost dose after whole-breast irradiation for DCIS?

A multi-institution retrospective study comparing wide local excision alone, wide local excision and whole-breast radiotherapy among 373 patients ≤ 45 years showed a reduced risk of relapse at 10 years in patients treated with a boost dose (86%) compared to no boost (72%).18 However, this study was potentially subject to selection bias, with the possibility that higher risk patients were more likely to have received a boost.19 The role of the boost and of hypofractionation is currently under investigation in the international BIG 3-07 trial. Patients with non-low-risk DCIS are randomised after whole-breast irradiation to a boost of 16 Gy in eight fractions or no boost. An external beam dose fractionation regimen (the standard of 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks) or a hypofractionated regimen of 42.5 Gy in 16 daily fractions are options that are included in the randomisation or can be selected in the trial. The primary end-point is time to local recurrence.

Role of adjuvant radiotherapy in invasive breast cancer

The overall impact of radiotherapy on local recurrence and survival is best appreciated from the 5-yearly updates of the Oxford overview of randomised trials of radiation after both breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy. The conclusions have changed dramatically since the first overview in 1978, which showed an adverse effect of RT on survival after mastectomy,21 largely due to the adverse effects of excessive cardiac irradiation from now obsolete orthovoltage techniques.

However, in 2005, the first evidence emerged of the beneficial effect of a reduction in local recurrence from RT on the overall survival23 of 42 000 women in 78 randomised trials.

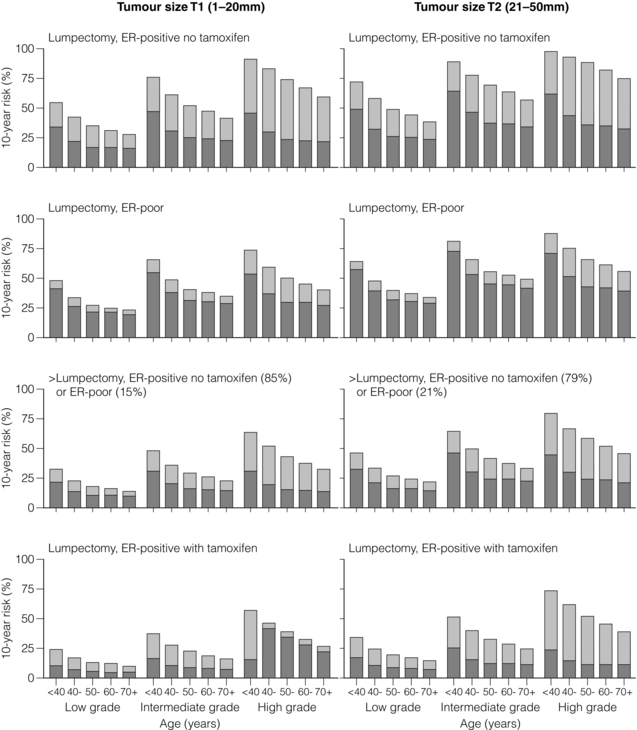

This ratio was confirmed in a more recent meta-analysis confined to over 10 000 women of trials of breast-conserving surgery with or without adjuvant whole breast irradiation.24 It should be noted that the primary end-point in the latter overview has been changed from previous radiotherapy overviews to include any first recurrence, whether this is locoregional or metastatic. The overall impact of adjuvant radiotherapy is an impressive 50% reduction in the risk of any first recurrence. However, the absolute benefits of radiotherapy are less in older lower-risk patients (Fig. 15.1). The 10-year risk of any recurrence was reduced by radiotherapy by 15.7% (35% to 19.3%; 95% CI 13.7–17.7, 2P < 0.00001) and the 15-year mortality fell from 25.2% to 21.4% (an absolute reduction of 3.8%; 95% CI 1.6–6.0, 2P = 0.00005). In 7287 pN0 patients, the equivalent risk was reduced from 31% to 15.6%, which is a 15.4% absolute reduction (95% CI 13.2–17.6, 2P < 0.00001) with a 3.3% absolute reduction in mortality from 20.5% to 17.2%. In pN1 (1050 patients) the 10-year reduction in risk of recurrence was greater (21.2%; 95% CI 14.5–27.9, 2P < 0.00001) from 63.7% to 42.5% with an 8.5% reduction in 15-year breast cancer mortality (95% CI 1.8–15.2, 2P = 0.01) from 51.3% death to 42.8%. The risk of any first recurrence at 10 years was influenced by tumour size, age, grade, use of tamoxifen, oestrogen receptor (ER) status and extent of local breast surgery (Fig. 15.2). The proportional reduction in first recurrence is similar irrespective of age. However, the absolute reduction in risk is much less for women > 70 years. Most recurrences (75%) were locoregional and were higher in the no RT groups (25%) compared to 8% in the RT arms. The dominant effect on locoregional recurrence from RT was in the first year but there was a lesser but still substantial impact up to 9 years.

Figure 15.1 Absolute 10-year risks (%) of any (locoregional or distant) first recurrence with and without radiotherapy (RT) following breast-conserving surgery (BCS) in pathologically node-negative women by patient and trial characteristics, as estimated by regression modelling of data for 7287 women. Bars show 10-year risks in women allocated to BCS only. Dark sections show 10-year risks in women allocated to BCS plus RT, light sections show absolute reduction with RT. ER, oestrogen receptor. Reprinted from The Lancet. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10 801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 378 (9804):1707–16. With permission from Elsevier.

Figure 15.2 Absolute reduction in 15-year risk of breast cancer death with radiotherapy (RT) after breast-conserving surgery versus absolute reduction in 10-year risk of any (locoregional or distant) recurrence. Women with pNO disease are subdivided by the predicted absolute reduction in 10-year risk of any recurrence suggested by regression modelling (pNO large ≥ 20%, pNO intermediate 10–19%, pNO lower<10%). Vertical lines are 95% CIs. Sizes of dark boxes are proportional to amount of information. Dashed line: one death from breast cancer avoided for every four recurrences avoided. pNO, pathologically node negative; pN+, pathologically node positive. Reprinted from The Lancet. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10 801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 378(9804):1707–16. With permission from Elsevier.

Is there a subgroup of patients from whom postoperative radiotherapy can be omitted?

Six hundred and thirty-six women, 70 years or older with T1, N0, M0 breast tumours, were randomised after breast-conserving surgery and tamoxifen to whole-breast irradiation or no further treatment. The difference in local recurrence was 3% at 5 years (4% vs. 1%) in favour of adjuvant irradiation.25

Breast oedema, skin fibrosis and pain were all more frequent in the irradiated group. In an accompanying editorial27 the value of radiotherapy was questioned given the small difference in local recurrence. However, no axillary surgical staging procedure was included in this study so it is possible that the some higher risk, node-positive patients were enrolled. In addition, as the authors acknowledge, the trial was underpowered. It is well recognised that there is a persistent pattern of local recurrence of up to 1% per year at least up to 10 years.28 This concern is validated by the update of the CALGB trial showing that at a median follow-up of 10.5 years, the difference in local recurrence has increased to 7% (9% vs. 2%).26 Of the 43% of patients who had died only 7% of deaths were due to breast cancer, reflecting the competing risks of death from non-breast cancer causes, predominantly vascular, in older patients with breast cancer.

Two additional trials shed light on the possibility of the omission of RT in some patients. The Italian 55-75 trial29 randomised 749 women with T (< 2.5 cm) N0/1, M0 breast cancer to whole-breast irradiation (50 Gy in 2-Gy fractions) after quadrantectomy and systemic therapy. For N0 patients, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was undertaken. SLNB-positive patients were additionally treated by axillary clearance. This trial is not directly comparable to the CALGB trial since it was not exclusive to older patients and higher risk patients with one to three involved nodes were included as well as hormone receptor-positive and -negative tumours. At a median follow-up of 53 months, the cumulative incidence of IBTR was 2.5% in the surgery-alone arm and 0.7% in the surgery plus radiotherapy arm. The smaller difference in IBTR (1.8%) in the Italian 55-75 trial compared to the CALGB trial largely reflects the greater volume of breast tissue resected by quadrantectomy compared to lumpectomy. The PRIME II trial,30 currently in the follow-up phase, included over 1300 patients ≥ 65 years with T < 3 cm pathologically axillary node-negative breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery (minimum 1 mm clear margin) and adjuvant endocrine therapy who were randomised to whole-breast irradiation (40–50 Gy) or no whole-breast radiotherapy. Other randomised trials of breast-conserving surgery with or without postoperative radiotherapy that have included but were not limited to older patients do not provide an answer to the question of the omission of postoperative radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery. In a Canadian trial,31 age was an independent risk factor with a higher locoregional recurrence rate (LRR) in women over the age of 50. However, a low-risk group with an LRR < 10% could not be identified. In the Milan III trial, women over the age of 55 years had a lower risk of recurrence (3.8% vs. 8.8% for the whole population).32 In the Scottish conservation trial,33 there was a trend to a lower recurrence rate with age, particularly between 60 and 70 years. No difference in local recurrence was observed in the NSABP B-06 trial for women older or younger than 50 years.34 The upper age of the trial, however, is not stated.

It should be noted, however, that 5-year local recurrence rates in more recently published studies of breast conservation are falling to around 3%.36 In part this is due to better imaging, screening, surgery and systemic therapy, particularly the introduction of aromatase inhibitors. So the absolute benefits in local control from whole-breast irradiation for older patients are likely to diminish. There is a need to identify better markers of women who are genuinely at low risk of local recurrence to better define clinical ‘low-risk’ categories and then provide level I evidence to underpin this approach.

Breast boost after breast-conserving surgery for invasive breast cancer

There is level I evidence that a boost of irradiation to the site of excision after breast-conserving surgery improves local control in older as well as young patients. The EORTC boost trial randomised over 5000 T1/2, N0, NIM0 patients after breast-conserving surgery with clear margins and whole-breast irradiation (50 Gy) to a boost of 16 Gy in eight fractions or no boost. The original analysis37 at 5 years of follow-up showed that the benefit in local control was only statistically significant in women under the age of 50. However, at 10 years of follow-up,38 all age groups were shown to benefit, although the reduction in local recurrence (7.3% vs. 3.8%) was only 3.5% in the over 60 years of age group.

Impact of adjuvant whole-breast radiotherapy on quality of life

It might be assumed that the quality of life of older patients treated with postoperative radiotherapy would be worse than for patients treated by breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant endocrine therapy alone due to the burden of attending for several weeks of radiotherapy. However, there is good evidence that adjuvant radiotherapy is well tolerated by the majority of older patients.39,40 The only trial to address this issue is the PRIME I trial. It randomised 255 T1/2, N0, M0 patients treated by breast-conserving surgery and endocrine therapy to whole-breast radiotherapy (40–50 Gy) or no further therapy. There was no overall difference in global quality of life measured by the EORTC breast QoL measures41 at 5 years.

Hypofractionated dose fractionation regimens

In the UK START A trial, two postoperative hypofractionated dose fractionation regimens, 39 Gy in 13 fractions of 3.2 Gy and 41.6 Gy in 13 fractions of 3 Gy, were compared with 50 Gy in 25 fractions in 2236 women treated by mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery. All regimens were given over 5 weeks. The 5-year LRR was 3.6%, 3.5% and 5.2% for 50 Gy, 41.6 Gy and 39 Gy respectively.42 In the START B trial, 40 Gy in 15 fractions over 3 weeks was compared to 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks in 2215 women after primary surgery. The 5-year locoregional recurrence rates were 2.2% and 3.3% for 40-Gy and 50-Gy regimens respectively. Breast cosmesis was superior in the 40-Gy arm. In both trials the shorter regimens provided similar locoregional control to the standard 50 Gy. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has adopted a 40 Gy in 15 fractions dose fractionation regimen as the new UK standard for adjuvant postoperative radiotherapy.45 In the Canadian trial,44 1234 patients with T1/2 axillary node-negative breast cancer were randomised after breast-conserving surgery with clear margins to a hypofractionated regimen (42.5 Gy in 16 fractions over 3.5 weeks) of whole-breast irradiation or to 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks. No boost was given to the site of excision. At 10 years the local recurrence rate was 6.7% in the standard arm and 6.2% in the test arm. Breast cosmesis was similar in both arms of the trial. There has been little consensus on the generalisability of the findings of the START and Canadian hypofractionation trials. The recent ASTRO Consensus statement recommends that hypofractionated whole-breast irradiation (HF-WBI) is confined to women 50 years or older with T1/2 N0 disease not receiving chemotherapy or nodal irradiation.46 There is uncertainty about the long-term effects of hypofractionated radiotherapy on the heart. The ASTRO consensus statement therefore advises that HF-WBI should only be used where the heart is excluded from the radiation fields. In contrast, 40 Gy in 15 fractions has been endorsed by the guidelines of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence for postconservation and postmastectomy irradiation,45 a much broader application of shortened fractionation.

The results of other hypofractionated dose fractionation regimens have been reported in non-randomised studies. Kirova et al.,47 in a series of 317 patients aged 70 years or over treated with 32.5 Gy in five fractions once weekly of 6.5 Gy, found similar all-cause-free, local recurrence-free and metastasis-free survival to conventionally fractionated radiotherapy of 50 Gy in 25 daily fractions over 5 weeks. Acute skin toxicity with the HF-WBI regimen was acceptable and no different from the conventionally fractionated patients of similar age. Cosmesis was also similar. However, late complications measured on the LENT-SOMA (late effects normal tissue – subjective, objective management, analytic) showed a higher incidence of grade 1–2 fibrosis (33%) with HF-WBI compared with conventionally fractionated therapy (15%). Similar rates of late effects were seen using the same hypofractionated regimen.48

Partial breast irradiation

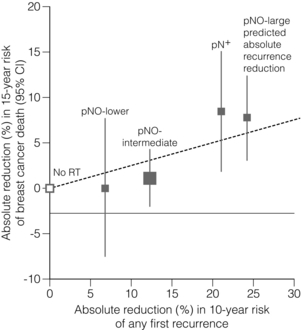

Partial breast irradiation (PBI) in which adjuvant irradiation is delivered exclusively or in higher dosage to the primary site than the rest of the breast is being investigated in a number of randomised trials. The rationale for this approach is that local recurrences occur predominantly at or close to the site of excision.34,49 A number of techniques are being studied in clinical trials, including external beam import low,50 intraoperative kilovoltage (TARGIT)51 (Fig. 15.3)/electron therapy (ELIOT)52 and intraoperative or postoperative brachytherapy.53 The rationale and indications for these techniques have recently been reviewed.54 Of particular interest to older patients are single fraction intraoperative techniques, which avoid the inconvenience of attendance for several weeks of daily outpatient radiotherapy. The only published randomised trial of PBI is the TARGIT A trial,51 which randomised predominantly low-risk postmenopausal patients randomised to intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) with the Intrabeam device (Fig. 15.3) using 50 kV X-rays (20 Gy to the surface of the applicator) or to whole-breast irradiation. The local recurrence rate was very low in both arms of the trial but the follow-up was relatively short (4 years). The Kaplan–Meier estimate of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence at 4 years was 1.20% (95% CI 0.53–2.71) in the targeted intraoperative radiotherapy group (Fig. 15.3) and 0.95% (95% CI 0.39–2.31) in the external beam radiotherapy group. The results, however, are confounded by the option of investigators to supplement IORT with external beam if the investigator considered that there were additional risk factors for recurrence on the excision specimen.55,56The main drawback of the technique is that irradiation is delivered before the margins of excision are assessed on the operative specimen. Intraoperative electrons (3–12 MeV) using a mobile linear accelerator delivering 21 Gy to the 90% isodose are being studied by the Milan group, shielding the chest wall with lead if required.52

Figure 15.3 Targeted intraoperative radiotherapy techniques with the Intrabeam system. (a) The applicator being placed in the tumour bed. (b) The X-ray source is delivered to the tumour bed by use of a surgical support stand. The sterile applicator is joined with a sterile drape that is used to cover the stand during treatment delivery. Reprinted from The Lancet. Vaidya JS, Joseph DJ, Tobias JS et al. Targeted intraoperative radiotherapy versus whole breast radiotherapy for breast cancer (TARGIT-A trial): an international, prospective, randomised, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010; 376(9735):91–102. With permission from Elsevier.

Postoperative brachytherapy after lumpectomy using low-dose-rate implants over 4–5 days or high dose rate typically twice daily for 5 days has yielded low local recurrence rates.57,58 Largely in response to the adoption of PBI outside of clinical trials predominantly in the USA and some parts of Europe, consensus guidelines for the use of PBI have been published by ASTRO and GEC, ESTRO.46,53 While these guidelines may be a pragmatic approach to PBI, they are not based on level I evidence.

Postmastectomy irradiation

It has long been established that postmastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) reduces the relative risk of locoregional recurrence by about two-thirds in randomised trials.59–62 However, the impact on overall survival has been controversial.22,63,64

An explanation for this survival benefit is that tumour cells in local recurrence may have a greater proclivity to metastasise than the original primary tumour.65 Support is lent to this idea by the fact that patients with local recurrence have a higher breast cancer mortality than patients with a new primary breast tumour.66,67 As Chung and Harris65 point out, there is a reduction in local failure rate from chemotherapy alone (50% in ER-positive disease at 5 years and one-third irrespective of ER status), although where the combination of chemotherapy and radiation achieves more impact on local control than either treatment alone.68,69

Role of postmastectomy radiotherapy in intermediate risk breast cancer

The role of PMRT in the intermediate-risk group (i.e. women with a 10–19% 10-year risk of locoregional recurrence) with one to three involved axillary nodes or axillary node negative but with other risk factors, e.g. grade 3 histology and/or lymphovascular invasion remains controversial with proponents and sceptics of routine PMRT in this setting.70,71 What is unclear is the generalisability of the Danish and British Columbia trials to contemporary practice. The locoregional failure rate in the Danish and Canadian trials was greater than in many contemporary non-randomised American series. This might in part be explained by suboptimal axillary surgery with a median of only seven nodes removed in the Danish trials and 11 in the British Columbia trial. An additional criticism was the intensity of chemotherapy.72 Furthermore, the duration of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) changed over the course of the Danish premenopausal trial. Early in the trial CMF was given for 12 months but this was subsequently shortened to 6 months. In addition only 1 year of adjuvant tamoxifen was given in the Danish 82b trial in contrast to the current standard of 5 years. The risk of local relapse in intermediate-risk patients was of the order of 5–15%73 and better quality surgery and anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy will reduce this so that further reductions in risk by PMRT might be too low to justify giving irradiation to all such women.

In response to concerns about the adequacy of axillary surgery in the Danish trials, a subgroup analysis of 1000 patients from the DBCG 82b and 82c trials was undertaken. It showed a survival advantage in women with one to three involved nodes as well as those with four or more nodes. The authors and others74 interpreted this analysis as implying that all node-positive patients should receive postmastectomy irradiation. Others have argued that the somewhat historic Danish trial data are not translatable to contemporary practice71 since patients with similar levels of risk are now treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy rather than the CMF-based regimens used in the Danish and Canadian high-risk premenopausal studies.59,61

The role of PMRT in ‘intermediate-risk’ breast cancer is currently being investigated in the MRC/EORTC BIG 2- 04 SUPREMO trial.75 This includes a biological substudy TRANS-SUPREMO designed to analyse molecular markers associated with risk of relapse. Biological factors may be important in selecting patients for PMRT. Of note, an unplanned subgroup analysis of more than 1000 patients in the Danish 82b and 82c trials by ER, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-2) status showed that the survival benefit of PMRT was confined to hormone receptor-positive patients and that hormone receptor-negative or triple negative or HER-2-positive patients did not derive a survival advantage.76 A possible explanation is that these high-risk patients already have disseminated disease on which PMRT is likely to have little impact.

Adjuvant radiotherapy in older patients

Local control in breast cancer is as important for older patients as it is for their younger counterparts, whether after mastectomy or after breast-conserving surgery. Radiotherapy, in conjunction with surgery, continues to play a key role in achieving this. The Oxford overview of randomised trials of adjuvant radiotherapy demonstrates that good local control contributes to reducing breast cancer mortality.77 There is, however, little level I evidence for the role of adjuvant radiotherapy in breast cancer in older patients largely due to the historical exclusion of patients over the age of 70 from clinical trials. Extrapolation of the results of trials of adjuvant radiotherapy in younger patients to older patients may not be appropriate given the different biology of breast cancer in older patients and the competing risks of non-breast cancer death in this age group. In general older patients tend to have more favourable biological prognostic factors than younger patients with a higher proportion of hormone receptor-positive tumours. This advantage is counterbalanced by exclusion of older patients from national breast screening programmes. As a result, presentation with locally advanced disease with associated poor prognosis is still seen in older women.

Axillary irradiation

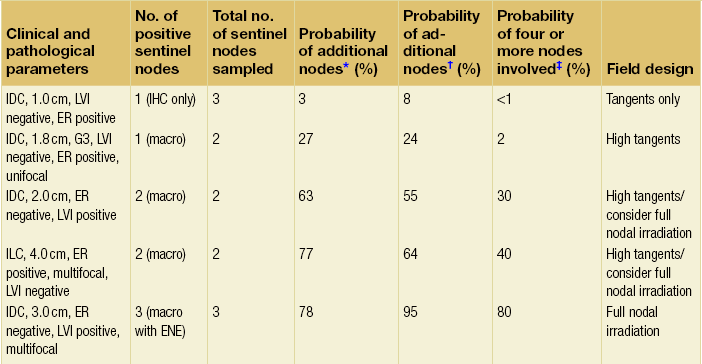

With the rapid replacement of routine axillary clearance by sentinel node biopsy as a less morbid method of staging the axilla, the optimal management of patients with micro- or macrometastases in the axillary nodes and the role of axillary irradiation is a focus of ongoing current debate. Central to this discussion is the interpretation of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 phase III trial,78 which randomised patients with T1–T2 sentinel node biopsy-positive invasive breast cancer treated by breast-conserving surgery to no further surgery or to axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Patients with micro- or macrometastases in one or two sentinel nodes were included. The whole breast was irradiated by tangential fields and systemic therapy given as appropriate. This was a non-inferiority trial with an intended target accrual of 1900 patients, although less than half were actually accrued. At a median follow-up of 6.3 years there was no difference found in 5-year rates of locoregional recurrence (1.6% for SLNB alone compared to 3.1% in the ALND arm) or in overall survival (92.5% vs. 91.8% respectively). The hazard ratio for overall survival was 0.79 (90% CI 0.56–1.11) When adjusted for age and systemic therapy, the HR rose to 0.87 (90% CI 0.62–1.23). Both these figures were interpreted by the authors as demonstrating non-inferiority of the SLNB-alone arm and endorsing a policy of observation only in SLNB patients without the need for axillary irradiation. However, there are major issues with this trial. Firstly, the trial was closed prematurely after the accrual of 900 patients, less than half of the planned target accrual of 1900 patients. The trial was therefore potentially underpowered to detect the primary end-point of overall survival (500 deaths were needed to have 90% power to confirm non-inferiority of SLNB compared to axillary node dissection) although it did reach its statistical end-point. Secondly, there was no quality assurance of the radiotherapy of the trial to confirm that there was no difference in field placements between the two arms of the trial. In the SLNB arm, radiation oncologists might have been tempted to raise the upper border of tangential fields in order to cover more of the axillary nodes. This is currently being investigated. If there was genuinely no difference then this would be reassuring that there was no bias in RT technique. A number of possible explanations for the low event rates in the axilla have been postulated,79 including the low-risk population studied, the impact of systemic therapy and immune surveillance mechanisms suppressing axillary disease. Certainly event rates in contemporary trials of therapy in early breast cancer have been falling. However, the impact of immune surveillance mechanisms in dealing with axillary disease is poorly understood and remains speculative. To address concerns about leaving residual axillary disease untreated after SLNB, a number of algorithms have been developed to predict the probability of non-sentinel lymph node involvement. These algorithms have been tested retrospectively, generally in small cohorts of a few hundred patients with positive sentinel nodes. In the recent study, for example, on a cohort of 159 patients from China,80 the Cambridge and Mou models outperformed the Mayo, Tenon, MD Anderson, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Turkish, Llubjana, SNUH and Louisville models. However, there remain limitations to these models in predicting residual axillary disease. There is at present limited data to inform best practice, and such data may not be an argument to convince all surgeons that observation only is an option for selected patients with involved nodes following SLNB. An option to complete axillary dissection is axillary irradiation, as it is proven therapy to control axillary disease, although there is limited level I evidence. The Edinburgh randomised trial included patients treated by BCS and mastectomy and compared ALND to axillary RT in axillary lymph node sample-positive patients.81 It showed no difference in regional control at 5 years or in overall survival. The trial provided excellent data on axillary morbidity showing a low incidence of lymphoedema in the axillary RT arm but some long-term limitation of shoulder mobility. Higher levels of persistent lymphoedema complicated ANLD. The ongoing AMAROS trial82 is comparing ANLD and axillary irradiation in patients with sentinel node metastases. Identifying more reliably the subset of patients with sentinel node macrometastases who need axillary irradiation requires more level I evidence. In the absence of such evidence, a pragmatic approach to selecting higher risk patients on the basis of number of positive sentinel nodes, tumour size, ER status and presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion proposed by Haffty et al.79 (Table 15.1) is a reasonable pragmatic approach.

Table 15.1

Suggested approach for radiation field design in patients with positive sentinel node biopsy without axillary lymph node dissection

*On the basis of the Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center nomogram.

†On the basis of the MD Anderson Center nomogram.

Modified from Haffty BG, Hunt KK, Harris JR et al. Positive sentinel nodes without axillary dissection: implications for the radiation oncologist. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:4479–81.

Minimising radiation-induced cardiac morbidity

Older radiotherapy techniques that led to excess radiation-induced cardiac toxicity and mortality have been replaced by three-dimensional planning84 and breath holding techniques1 to minimise cardiac irradiation in left-sided tumours. In successive cohorts of patients treated in the USA, radiation-induced cardiac mortality has fallen.85 This almost certainly reflects the introduction of three-dimensional planning for breast cancer. Ischaemic heart disease is commoner in older patients. While the cardiac sequelae of adjuvant breast irradiation may take 10 years to manifest themselves, this latency may be within the life expectancy of older patients with early breast cancer. At least the same priority should be given to minimising cardiac irradiation in older as in younger patients.

References

1. Korreman, S.S., Pedersen, A.N., Nottrup, T.J., et al, Breathing adapted radiotherapy for breast cancer: comparison of free breathing gating with breath-hold technique. Radiother Oncol 2005; 76:311–318. 16153728

2. Haffty, B.G., Buchholz, T.A., McCormick, B., et al, Should intensity-modulated radiation therapy be the standard of care in the conservatively managed breast cancer patient? J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:2072–2074. 18285600

3. Hoover, S., Bloom, E., Patel, S., Review of breast conservation therapy: then and now. ISRN Oncol 2011; 2011:617593. 22229101

4. Pignol, J.P., Olivotto, I., Rakovitch, E., et al, A multicenter randomized trial of breast intensity-modulated radiation therapy to reduce acute radiation dermatitis. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:2085–2092. 18285602 In this trial, 358 patients with early breast cancer were randomised to standard radiotherapy (RT) with wedged fields or to intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT); 331 patients were analysed. IMRT significantly improved the dose distribution compared with standard radiation. Fewer patients treated with IMRT (31.2%) experienced moist desquamation during or up to 6 weeks after RT compared to 47.8% with standard treatment (P = 0.002). On multivariate analysis breast IMRT (P = 0.003) and smaller breast size (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with a lower risk of moist desquamation. The application of IMRT did not correlate with pain and quality of life, but moist desquamation did significantly correlate with pain (P = 0.002) and impaired quality of life (P = 0.003).

5. Barnes, N.L., Ooi, J.L., Yarnold, J.R., et al, Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Br Med J 2012; 344:e797. 22378935

6. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, EORTC Radiotherapy Group, Bijker, N., Meijnen, P., Peterse, J.L., et al, Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma-in-situ: ten-year results of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized phase III trial 10853 – a study by the EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:3381–3387. 16801628 This randomised trial provides evidence of the effectiveness of postoperative radiotherapy in reducing ipsilateral DCIS and invasive recurrence (level I evidence).

7. Fisher, B., Land, S., Mamounas, E., et al, Prevention of invasive breast cancer in women with ductal carcinoma in situ: an update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. Semin Oncol 2001; 28:400–418. 11498833

8. Wapnir, I.L., Dignam, J.J., Fisher, B., et al, Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103:478–488. 21398619 This paper provides the longest follow-up data among randomised trials of postoperative radiotherapy (RT) for DCIS (207 months for the B-17 trial and 163 months for the B-24 trial). RT reduced IBTR by 52% in the lumpectomy + RT arm compared with lumpectomy alone (B-17, HR of risk of IBTR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.33–0.69, P < 0.001). Lumpectomy + RT + tamoxifen reduced IBTR by 32% compared with lumpectomy + RT + placebo (B-24, HR of risk of IBTR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.49–0.95, P = 0.025). The 15-year cumulative incidence of IBTR was 19.4% for lumpectomy alone, 8.9% for lumpectomy + RT (B-17), 10.0% for lumpectomy + RT + placebo (B-24), and 8.5% for lumpectomy + RT + tamoxifen (level I evidence).

9. Houghton, J., George, W.D., Cuzick, J., et alUK Coordinating Committee on Cancer ResearchDuctal Carcinoma In Situ Working PartyDCIS trialists in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, Radiotherapy and tamoxifen in women with completely excised ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 362:95–102. 12867108 This was a randomised controlled trial with a 2 × 2 factorial design in which investigators could elect to give radiotherapy and randomise to +/− tamoxifen or elect tamoxifen and randomise to +/− radiotherapy. Radiotherapy reduces ipsilateral DCIS and invasive recurrence (level I evidence).

10. Holmberg, L., Garmo, H., Granstrand, B., et al, Absolute risk reductions for local recurrence after postoperative radiotherapy after sector resection for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:1247–1252. 18250350 This randomised trial showed a particular benefit of adjuvant postoperative in older patients and less impact in women under the age of 50. There was no confounding effect on age by focality, lesion size, completeness of excision or method of detection. There was no subgroup that had a low risk without radiotherapy (level I evidence).

11. Goodwin, A., Parker, S., Ghersi, D., et al, Post-operative radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4 CD000563. 19588320 This is a meta-analysis of the four randomised trials assessing the role of adjuvant radiotherapy after wide local excision of DCIS (level I evidence).

12. Julien, J.P., Bijker, N., Fentiman, I.S., et al, Radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: first results of the EORTC randomised phase III trial 10853. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. Lancet 2000; 355:528–533. 10683002 This is the first publication of the EORTC DCIS trial assessing the role of adjuvant irradiation at a median follow-up of 4.25 years. The 4-year local relapse-free rate was 84% with local excision alone compared to 91% with wide local excision + radiotherapy (log rank P = 0.005; hazard ratio 0.62). There were similar reductions in the risk of invasive (40%, P = 0.04) and non-invasive (35%, P = 0.06) local recurrence (level I evidence).

13. Patani, N., Cutuli, B., Mokbel, K., Current management of DCIS: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008; 111:1–10. 17902049

14. Bijker, N., Peterse, J.L., Duchateau, L., et al, Risk factors for recurrence and metastasis after breast-conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 10853. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:2263–2271. 11304780

15. Page, D.L., Lagios, M.D., Pathologic analysis of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) B-17 trial. Unanswered questions remaining unanswered considering current concepts of ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer 1995; 75:1219–1222. 7882273

16. Hughes, L.L., Wang, M., Page, D.L., et al, Local excision alone without irradiation for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:5319–5324. 19826126

17. Fisher, E.R., Dignam, J., Tan-Chiu, E., et al, Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer 1999; 86:429–438. 10430251

18. Omlin, A., Amichetti, M., Azria, D., et al, Boost radiotherapy in young women with ductal carcinoma in situ: a multicentre, retrospective study of the Rare Cancer Network. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7:652–656. 16887482

19. Stillie, A., Kunkler, I., Kerr, G., et al, Is a radiotherapy boost truly beneficial? Lancet Oncol 2006; 7:795–796. 17012041

20. Williamson, D., Dinniwell, R., Fung, S., et al, Local control with conventional and hypofractionated adjuvant radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in-situ. Radiother Oncol 2010; 95:317–320. 20400190

21. Cuzick, J., Stewart, H., Peto, R., et al, Overview of randomized trials comparing radical mastectomy without radiotherapy against simple mastectomy with radiotherapy in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rep 1987; 71:7–14. 3539330

22. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, Favourable and unfavourable effects on long-term survival of radiotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2000; 355:1757–1770. 10832826

23. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTG), Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trial. Lancet 2005; 365:1687–1717. 15894097 This was the first Oxford overview of radiotherapy trials that identified a link between locoregional control by radiotherapy and survival.

24. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, Effects of radiotherapy on 10-year recurrence and 15- year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 378:1707–1716. 22019144 This, the latest overview of randomised trials of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery, uses first recurrence of any type (locoregional or metastatic) in contrast to first locoregional recurrence in previous overviews of breast radiotherapy. It provides longer term data that the ‘4:1 ratio’ (for every four local recurrences avoided, one breast cancer death is avoided) still holds.

25. Hughes, K.S., Schnaper, L.A., Berry, D., et al, Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women 70 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:971–977. 15342805 This is the only randomised trial addressing the need for radiotherapy in low-risk hormone receptor breast cancer in older patients after breast-conserving surgery receiving adjuvant tamoxifen.

26. Hughes, K.S., Schnaper, L.A., Cirrincione, C., et al, Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 or older with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:507. 20644101

27. Smith, I.E., Ross, G.M., Breast radiotherapy after lumpectomy – no longer always necessary. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1021–1023. 15342811

28. Montgomery, D.A., Krupa, K., Jack, W.J., et al, Changing pattern of the detection of locoregional relapse in breast cancer: the Edinburgh experience. Br J Cancer 2007; 96:1802–1807. 17533401

29. Tinterri, C., Gatzemeier, W., Zanini, V., et al, Conservative surgery with and without radiotherapy in elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer: a prospective randomised multicentre trial. Breast 2009; 18:373–377. 19910194

30. Kunkler, I., PRIME II breast cancer trial. Clin Oncol 2004; 16:447–448. 15490804

31. Clarke, R.M., McCulloch, P.B., Levine, M.N., et al, Randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of breast irradiation following lumpectomy and axillary dissection for node-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992; 84:683–689. 1314910

32. Veronesi, U., Luini, A., Del Vecchio, M., et al, Radiotherapy after breast-preserving surgery in women with localized cancer of the breast. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:1587–1591. 8387637

33. Forrest, A.P., Stewart, H.J., Everington, D., Scottish Cancer Trials Breast Group, Randomised controlled trial of conservation therapy for breast cancer: 6-year analysis of the Scottish trial. Lancet 1996; 348:708–713. 8806289

34. Fisher, B., Anderson, S., Redmond, C.K., et al, Reanalysis and results after 12 years of follow-up in a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy with lumpectomy with or without irradiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1456–1461. 7477145

35. Wildiers, H., Kunkler, I., Biganzoli, L., et al, Management of breast cancer in elderly individuals: recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8:1101–1115. 18054880 This international consensus statement includes a summary of trials assessing the role of adjuvant radiotherapy in older patients (level I evidence).

36. Mannino, M., Yarnold, J.R., Local relapse rates are falling after breast conserving surgery and systemic therapy for early breast cancer: can radiotherapy ever be safely withheld? Radiother Oncol 2009; 90:14–22. 18502528

37. Bartelink, H., Horiot, J.C., Poortmans, P., et al, Recurrence rates after treatment of breast cancer with standard radiotherapy with or without additional radiation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1378–1387. 11794170

38. Bartelink, H., Horiot, J.C., Poortmans, P.M., et al, Impact of a higher radiation dose on local control and survival in breast-conserving therapy of early breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized boost versus no boost EORTC 22881-10882 trial. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:3259–3265. 17577015

39. Wyckoff, J., Greenberg, H., Sanderson, R., et al, Breast irradiation in the older woman: a toxicity study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:150–152. 8126327

40. Huguenin, P., Glanzmann, C., Lütolf, U.M., Acute toxicity of curative radiotherapy in elderly patients. Strahlenther Onkol 1996; 172:658–663. 8972750

41. Williams, L.J., Kunkler, I.H., King, C.C., et al, A randomised controlled trial of post-operative radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery in a minimum-risk population. Quality of life at 5 years in The PRIME trial. Health Technol Assess 2011; 15:1–57. 22059955 This is the only published randomised trial assessing the impact of the omission of adjuvant whole-breast irradiation on quality of life in operable breast managed by breast-conserving surgery. It showed no overall impact on quality of life (level I evidence).

42. START Trialists’ GroupBentzen, S.M., Agrawal, R.K., Aird, E.G., et al, The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) Trial A of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9:331–341. 18356109 This randomised trial assessed the fraction sensitivity of two postoperative hypofractionated radiotherapies after breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy compared with standard dose fractionation (level I evidence).

43. START Trialists’ Group, Bentzen, S.M., Agrawal, R.K., Aird, E.G., et al, The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) Trial B of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 2008; 371:1098–1107. 18355913 This randomised trial assessed the fraction sensitivity of a postoperative hypofractionated radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy compared to standard dose fractionation (level I evidence).

44. Whelan, T.J., Pignol, J.P., Levine, M.N., et al, Long-term results of hypofractionated radiation therapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:513–520. 20147717 This randomised trial showed equivalent local control for a hypofractionated dose schedule compared to standard fractionation in postmenopausal node-negative women following breast-conserving surgery (level I).

45. NICE. Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2009.

46. Smith, B.D., Arthur, D.W., Buchholz, T.A., et al, Accelerated partial breast irradiation consensus statement from the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). J Am Coll Surg 2009; 209:269–277. 19632605

47. Kirova, Y.M., Campana, F., Savignoni, A., et al, Breast-conserving treatment in the elderly: long-term results of adjuvant hypofractionated and normofractionated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009; 75:76–81. 19168297

48. Ortholan, C., Hannoun-Levi, J.M., Ferrero, J.M., et al, Long-term results of adjuvant hypofractionated radiotherapy for breast cancer in elderly patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 61:154–162. 15629606

49. Veronesi, U., Cascinelli, N., Mariani, L., et al, Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1227–1232. 12393819

50. Coles, C., Yarnold, J., IMPORT Trials Management Group, The IMPORT trials are launched (September 2006). Clin Oncol 2006; 18:587–590. 17051947

51. Vaidya, J.S., Joseph, D.J., Tobias, J.S., Targeted intraoperative radiotherapy versus whole breast radiotherapy for breast cancer (TARGIT-A trial): an international, prospective, randomised, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010; 376:91–102. 20570343

52. Veronesi, U., Orecchia, R., Luini, A., et al, Intraoperative radiotherapy during breast conserving surgery: a study on 1,822 cases treated with electrons. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 124:141–151. 20711810

53. Polgár, C., Van Limbergen, E., Pötter, R., et al, Patient selection for accelerated partial-breast irradiation (ABPI) after breast-conserving surgery: recommendations of the Groupe Européen de Curiétherapie-European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO) breast cancer working group based on clinical evidence (2009). Radiother Oncol 2010; 94:264–273. 20181402

54. Stewart, A.J., Khan, A.J., Devlin, P.M., Partial breast irradiation: a review of techniques and indications. Br J Radiol 2010; 83:369–378. 20223911

55. Cameron, D., Kunkler, I., Dixon, M., et al, Intraoperative radiotherapy for early breast cancer. Lancet 2010; 376:1142. 20888983

56. Vaidya, J.S., Wenz, F., Bulsara, M., et al. Targeted intraoperative radiotherapy for early breast cancer: TARGIT-A trial-updated analysis of local recurrence and first analysis of survival. Cancer Research. 2012; 72(24):100s.

57. Vicini, F.A., Baglan, K.L., Kestin, L.L., et al, Accelerated treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:1993–2001. 11283132

58. Polgár, C., Sulyok, Z., Fodor, J., et al, Sole brachytherapy of the tumor bed after conservative surgery for T1 breast cancer: five-year results of a phase I/II study and initial findings of a randomized phase III trial. J Surg Oncol 2002; 80:121–128. 12115793

59. Overgaard, M., Hansen, P.S., Overgaard, J., et al, Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b Trial. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:949–955. 9395428

60. Overgaard, M., Jensen, M.B., Overgaard, J., et al, Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk postmenopausal breast-cancer patients given adjuvant tamoxifen: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82c randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 353:1641–1648. 10335782

61. Ragaz, J., Jackson, S.M., Le, N., et al, Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:956–962. 9309100

62. Ragaz, J., Olivotto, I.A., Spinelli, J.J., et al, Locoregional radiation therapy in patients with high-risk breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: 20-year results of the British Columbia randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97:116–126. 15657341

63. Whelan, T.J., Julian, J., Wright, J., et al, Does locoregional radiation therapy improve survival in breast cancer? A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18:1220–1229. 10715291

64. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer. An overview of the randomized trials. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1444–1455. 7477144

65. Chung, C.S., Harris, J.R., Post-mastectomy radiation therapy: translating local benefits into improved survival. Breast 2007; 16:S78–S83. 17714945

66. Smith, T.E., Lee, D., Turner, B.C., et al, True recurrence vs. new primary ipsilateral breast tumor relapse: an analysis of clinical and pathologic differences and their implications in natural history, prognoses, and therapeutic management. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 48:1281–1289. 11121624

67. Goldstein, N.S., Vicini, F.A., Hunter, S., et al, Molecular clonality determination of ipsilateral recurrence of invasive breast carcinomas after breast-conserving therapy: comparison with clinical and biologic factors. Am J Clin Pathol 2005; 123:679–689. 15981807

68. Fisher, B., Bryant, J., Dignam, J.J., et al, Tamoxifen, radiation therapy, or both for prevention of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after lumpectomy in women with invasive breast cancers of one centimeter or less. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20:4141–4149. 12377957

69. Fyles, A.W., McCready, D.R., Manchul, L.A., et al, Tamoxifen with or without breast irradiation in women 50 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:963–970. 15342804

70. Marks, L.B., Zeng, J., Prosnitz, L.R., One to three versus four or more positive nodes and postmastectomy radiotherapy: time to end the debate. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:2075–2077. 18445836

71. Russell, N.S., Kunkler, I.H., van Tienhoven, G., et al, Postmastectomy radiotherapy: will the selective use of postmastectomy radiotherapy study end the debate? J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:996–997. 19164209

72. Goldhirsch, A., Coates, A.S., Colleoni, M., et al, Radiotherapy and chemotherapy in high-risk breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:330–331. 9446031

73. Recht, A., Gray, R., Davidson, N.E., et al, Locoregional failure 10 years after mastectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy with or without tamoxifen without irradiation: experience of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17:1689–1700. 10561205

74. Poortmans, P., Evidence based radiation oncology: breast cancer. Radiother Oncol 2007; 84:84–101. 17599597

75. Kunkler, I.H., Canney, P., van Tienhoven, G., et alMRC/EORTC (BIG 2-04) SUPREMO Trial Management Group, Elucidating the role of chest wall irradiation in ‘intermediate-risk’ breast cancer: the MRC/EORTC SUPREMO trial. Clin Oncol 2008; 20:31–34. 18345543

76. Kyndi, M., Sørensen, F.B., Knudsen, H., Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2, and response to postmastectomy radiotherapy in high-risk breast cancer: the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:1419–1426. 18285604

77. Clarke, M., Collins, R., Darby, S., et al, Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005; 366:2087–2106. 16360786

78. Giuliano, A.E., Hunt, K.K., Ballman, K.V., et al, Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305:569–575. 21304082

79. Haffty, B.G., Hunt, K.K., Harris, J.R., et al, Positive sentinel nodes without axillary dissection: implications for the radiation oncologist. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:4479–4481. 22042942

80. Chen, K., Zhu, L., Jia, W., et al, Validation and comparison of models to predict non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Cancer Sci 2012; 103:274–281. 22054165

81. Chetty, U., Jack, W., Prescott, R.J., et al, Management of the axilla in operable breast cancer treated by breast conservation: a randomized clinical trial. Edinburgh Breast Unit. Br J Surg 2000; 87:163–169. 10671921

82. Hurkmans, C.W., Borger, J.H., Rutgers, E.J., EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative GroupRadiotherapy Cooperative Group, Quality assurance of axillary radiotherapy in the EORTC AMAROS trial 10981/22023: the dummy run. Radiother Oncol 2003; 68:233–240. 13129630

83. Katz, A., Smith, B.L., Golshan, M., et al, Nomogram for the prediction of having four or more involved nodes for sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:2093–2098. 18445838

84. Das, I.J., Cheng, E.C., Freedman, G., et al, Lung and heart dose volume analyses with CT simulator in radiation treatment of breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998; 42:11–19. 9747814

85. Giordano, S.H., Kuo, Y.F., Freeman, J.L., et al, Risk of cardiac death after adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97:419–424. 15770005