Chapter 9 The rheumatological system

The rheumatological history

Presenting symptoms (Table 9.1)

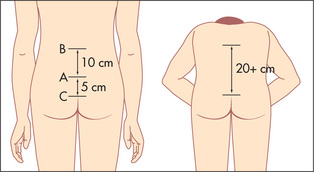

It is often useful to ask the patient to point to the painful place or area. For example, pain said to affect the knee may be in the popliteal fossa, the knee joint itself, or in the supra- or infra-patellar bursa. Remember also that pain in the knee or lower thigh may be referred from the hip (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Map of referral patterns for different joints

Adapted from Epstein O et al, Clinical Examination, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2008.

Find out if the symptoms are of an acute or chronic nature and whether they are getting better or worse. The effect of rest and exercise on the joint pain should be determined. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have joint symptoms which are worse after rest, while those with osteoarthritis have pain which is worse after exercise. Ask about the sequence of onset of joint involvement. Precipitating factors such as trauma should be noted. The causes of monoarthritis (single joint) and polyarthritis (more than one joint), and the patterns of polyarthritis in various diseases, are presented in Tables 9.2, 9.3 and 9.4.

TABLE 9.2 Causes of monoarthritis

| A single hot red swollen joint (acute monoarthritis) |

TABLE 9.3 Causes of polyarthritis

TABLE 9.4 Patterns of polyarthropathy

Morning stiffness

Ask about the presence of early-morning stiffness and the length of time that this stiffness lasts. Morning stiffness classically occurs in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthropathies, and the duration of stiffness is a guide to its severity. Stiffness after inactivity, such as sitting, is characteristic of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee.

Instability

Joint instability may be described by the patient as a ‘giving way’, or occasionally ‘coming out’, of the joint in certain conditions. This may be due to true dislocation (for example, with the shoulder or the patella) or alternatively to muscle weakness or ligamentous problems.

Back pain

This is a very common symptom. It is most often a consequence of local musculoskeletal disease.

Ask where the pain is situated, whether it began suddenly or gradually, whether it is localised or diffuse, whether it radiates to the limbs or elsewhere, and whether the pain is aggravated by movement, coughing or straining. Musculoskeletal pain is characteristically well localised and is aggravated by movement. If there is a spinal nerve root irritation there may be pain that occurs in a dermatomal distribution. This helps to localise the level of the lesion. Diseases such as osteoporosis (with crush fractures), infiltration of carcinoma, leukaemia or myeloma may cause progressive and unremitting back pain, which is often worse at night (Table 9.6). The pain may be of sudden onset but is usually self-limiting if it results from the crush fracture of a vertebral body. In ankylosing spondylitis the pain is usually situated over the sacroiliac joints and lumbar spine, it is also worse at night and is associated with morning stiffness. The pain of ankylosing spondylitis is typically better with activity which helps distinguish it from mechanical back pain.1,2 Pain from diseases of the abdomen and chest (e.g. dissecting abdominal or thoracic aortic aneurysm) can also be referred to the back.

| Age > 50 years |

| Cancer history |

| Weight loss (unexplained) |

| Pain on waking from sleep |

| Pain for longer than one month and unresponsive to simple analgesics |

| Fever |

| History of drug use by injection |

| Bowel or bladder dysfunction |

Limb pain

Musculoskeletal pain may be due to trauma or inflammation. Muscle disease such as polymyositis can present with an aching pain in the proximal muscles around the shoulders and hips, associated with weakness. Pain and stiffness in the shoulders and hips in patients over the age of 50 years may be due to polymyalgia rheumatica. The acute or subacute onset of symptoms in multiple locations suggests an inflammatory process. Bone disease

| Class | Assessment |

| Class 1 | Normal functional ability |

| Class 2 | Ability to carry out normal activities, despite discomfort or limited mobility of one or more joints |

| Class 3 | Ability to perform only a few of the tasks of the normal occupation or of self-care |

| Class 4 | Complete or almost complete incapacity with the patient confined to wheelchair or to bed |

such as osteomyelitis, osteomalacia, osteoporosis or tumours can cause limb pain. Inflammation of tendons (tenosynovitis) can produce local pain over the affected area.

Spinal stenosis can cause pseudo-claudication—pain on walking but relieved by leaning forward.

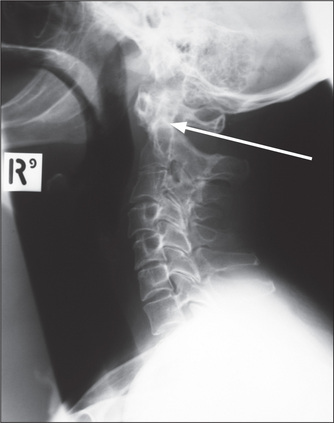

Nerve entrapment and neuropathy can both cause limb pain which is often associated with paraesthesiae or weakness. The usual cause is synovial thickening or joint subluxation—especially for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The vasculitis associated with the inflammatory arthropathies can also cause neuropathy leading to diffuse peripheral neuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex. Patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis often develop subluxation of the cervical spine at the atlanto-axial joint. This is caused by erosion of the transverse ligament around the posterior aspect of the odontoid process (dens). The patient may describe shooting paraesthesiae down the arms and an occipital headache. Neck flexion leads to indentation of the cord by the dens and can cause tetraplegia or sudden death. The abnormality may be obvious on lateral X-rays of the cervical spine (Figure 9.3). Injury to peripheral nerves can result in vasomotor changes and severe limb pain. This is called causalgia. Even following amputation of a limb, phantom limb pain may develop and persist as a chronic problem.

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Raynaud’s phenomenona is an abnormal response of the fingers and toes to cold. Classically, the fingers first turn white, then blue and finally red after exposure to cold. It is during the red phase that the pain may be most severe, but pain during the white stage may also be severe, as a result of ischaemia. Patients with Raynaud’s disease have Raynaud’s phenomenon without an obvious underlying cause. The disease tends to be familial and females are more likely to be affected. In connective tissue diseases, especially scleroderma, Raynaud’s phenomenon can occur and may lead to the formation of digital ulcers (Table 9.7).

TABLE 9.7 Causes of Raynaud’s phenomenon (white-blue-red fingers and toes in response to cold)

Dry eyes and mouth

Dry eyes and dry mouth are characteristic of Sjögren’s syndrome (Table 9.8). This syndrome may occur in isolation (primary Sjögren’s) and is very common in association with rheumatoid arthritis and other connective tissue disease. Mucus-secreting glands become infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells, which cause atrophy and fibrosis. The dry eyes can result in conjunctivitis, keratitis and corneal ulcers. Sjögren’s syndrome can also have an effect on other organs such as the lungs or kidneys.

| In this syndrome mucus-secreting glands are infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells, which cause atrophy and fibrosis of glandular tissue. |

| 1 Dry eyes: conjunctivitis, keratitis, corneal ulcers (rarely vascularisation of the cornea) |

| 2 Dry mouth |

| 3 Chest: infection secondary to reduced mucus secretion or interstitial pneumonitis |

| 4 Kidneys: renal tubular acidosis or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus |

| 5 Genital tract: atrophic vaginitis |

| 6 Pseudolymphoma: lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, which may rarely progress to a true (usually non-Hodgkin’s) lymphoma |

Note: This syndrome occurs in rheumatoid arthritis and with the connective tissue diseases.

Red eyes

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies and Behçet’sb syndrome but not rheumatoid arthritis may be complicated by iritis (eye pain with central scleral injection—a ‘red eye’—radiating out from the pupil) (see Figure 9.51, page 279). In other diseases, such as Sjögren’s, red eyes may be due to dryness, episcleritis or scleritis.

Treatment history

Document current and previous anti-arthritic medications (e.g. aspirin, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gold, methotrexate, penicillamine, chloroquine, steroids, anti-tumour necrosis factor α therapy, or other biological agents). Any side-effects of these drugs (e.g. gastric ulceration or haemorrhage, from aspirin) also need to be identified. Ask about physiotherapy and joint or tendon surgery in the past.

Past history

It is important to inquire about any history of trauma or surgery in the past. Similarly, a history of recent infection, including hepatitis, streptococcal pharyngitis, rubella, dysentery, gonorrhoea and tuberculosis, may be relevant to the onset of arthralgia or arthritis. A history of tick bite may indicate that the patient has Lyme disease. Inflammatory bowel disease can be associated with arthritis, as described on page 191. A history of psoriasis may indicate that the arthritis is due to psoriatic arthropathy. It is also important to inquire about any history of arthritis in childhood. The smoking history is important: rheumatoid arthritis is more common in smokers, and smoking adds to their already increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Examination anatomy

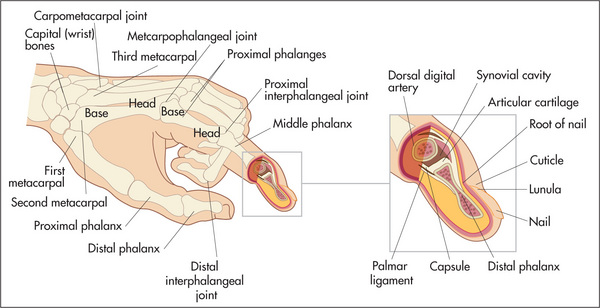

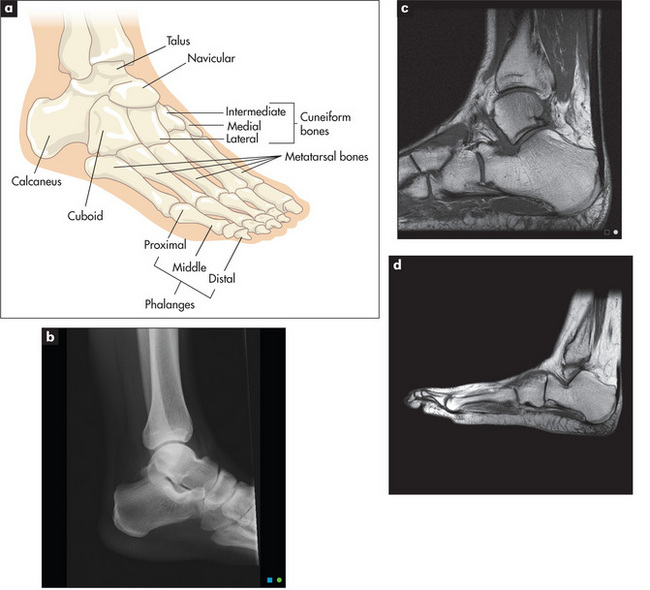

Joint structures (Figure 9.4)

Joint pain may be well localised if there is inflammation close to the skin, but deeper joint abnormalities may cause pain to be referred. The areas where joint pain is felt correspond to the innervation of the muscle attached to that joint—the myotome. For example, the glenohumeral joint of the shoulder and the posterior scapular muscles are supplied from C5 and C6, so pain over the shoulder or scapula may arise from any structure supplied from these nerve roots—including the shoulder muscles and joints but also the C5 and C6 segments of the spine. Figure 9.1 shows a map of approximate referral patterns for important joints.

The extra-articular structures that surround a joint—the ligaments, tendons and nerves—may also be the source of joint pain. Disease of the joint itself tends to limit movement of the joint in all directions, both active movement (moved by the patient) and passive movement (moved by the examiner). Extra-articular disease causes variable limitation of movement in different directions, and tends to cause more limitation of active than of passive movement.

The rheumatological examination

There are certain established ways of examining the joints and related structures3 and it is important to be aware of the numerous systemic complications of rheumatological diseases. The actual system of examination depends on the patient’s history and sometimes on the examiner noticing an abnormality on general inspection. Formal examination of all the joints is rarely part of the routine physical examination, but students should learn how to handle each joint properly and a formal examination is an important part of the evaluation of patients who present with joint symptoms or who have an established diagnosis and active symptoms. Diseases of the extra-articular soft tissues are particularly common.

General inspection

This is important for two reasons: first, it gives an indication of the patient’s functional disability, which is essential in all rheumatological assessments; and second, certain conditions can be diagnosed by careful inspection. Look at the patient as he or she walks into the room. Does walking appear to be painful and difficult? What posture is taken? Does the patient require assistance such as a stick or walking frame? Is there obvious deformity, and what joints does it involve? Note the pattern of joint involvement, which gives a clue about the likely underlying disease (Tables 9.2 to 9.4).

Principles of joint examination

Look

The first principle is always to compare right with left. Remember that joints are three-dimensional structures and need to be inspected from the front, the back and the sides. The skin is inspected for erythema indicating underlying inflammation and suggesting active, intense arthritis or infection, atrophy suggesting chronic underlying disease, scars indicating previous operations such as tendon repairs or joint replacements, and rashes. For example, psoriasis is associated with a rash and polyarthritis (inflammation of more than one joint). The psoriatic rash consists of scaling erythematous plaques on extensor surfaces. The nails are often also affected (page 252). Also look for a vasculitic skin rash (inflammation of the blood vessels of the skin), which can range in appearance from palpable purpura or livedo reticularis (bluish-purple streaks in a net-like pattern) to skin necrosis.

A small, firm, painless swelling over the back (dorsal surface) of the wrist is usually a synovial cyst—a ganglion.c A larger, localised, soft area of swelling of the dorsum of the wrist generally indicates tenosynovitis.

Deformity is the sign of a chronic, usually destructive, arthritis, and ranges from mild ulnar deviation of the metacarpophalangeal joints in early rheumatoid arthritis to the gross destruction and disorganisation of a denervated (Charcot’sd) joint (Figure 10.20, page 319). Deviation of the part of the body away from the midline is called valgus deformity, and towards the midline, varus deformity. For example, genu valgum means knock-kneed and genu varum, bow-legged.

Muscle wasting results from a combination of disuse of the joint, inflammation of the surrounding tissues and sometimes nerve entrapment. It tends to affect muscle groups adjacent to the diseased joint (e.g. quadriceps wasting with active arthritis of the knee) and is a sign of chronicity.

Assessment of individual joints

The hands and wrists (Figures 9.5 to 9.9)

Examination anatomy

Figure 9.5 Examination of the hands and wrists

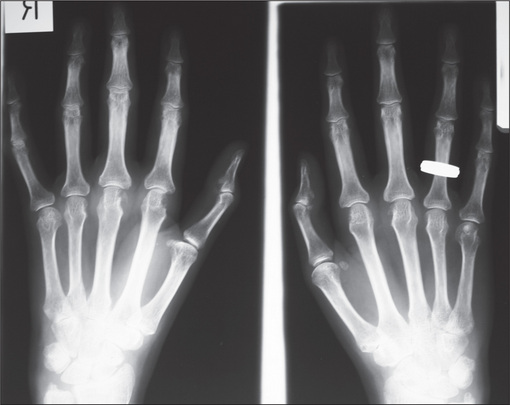

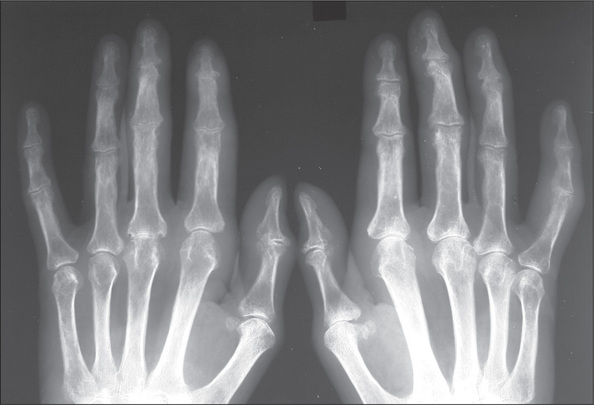

Figure 9.6 (right) X-ray of normal hand

Courtesy M Thomson, National Capital Diagnostic Imaging, Canberra.

History

Pain may be present in some or all of the joints. It is more likely to be vague or diffuse if it has radiated from the shoulder or neck or is due to carpal tunnel syndrome, and to be localised if it is due to arthritis. Stiffness is typically worse in the mornings in rheumatoid arthritis. Swelling of the wrist may indicate arthritis or tendon sheath inflammation. Swelling of individual joints suggests arthritis. Deformity of the fingers and hand due to rheumatoid arthritis or of the fingers as a result of arthritis or gouty tophi may be the presenting complaint. The sudden onset of deformity suggests tendon rupture. Locking or snapping of a finger (trigger finger) is typical of inflammation of a flexor tendon sheath (tenovaginitis). Loss of function is a serious problem when it involves the numerous functions of the hand and wrist. The history should include an assessment of the difficulties the patient has in using the hands and wrists. Neurological symptoms as a result of nerve compression may cause paraesthesiae or limitation of strength or of complicated hand functions.

Look

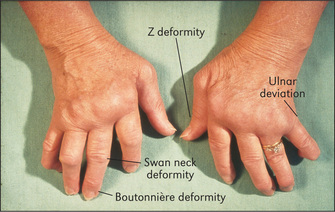

Go on to the metacarpophalangeal joints. Again note any skin abnormalities, swelling or deformity. Look especially for ulnar deviation and volar (palmar) subluxation of the fingers. Ulnar deviation is deviation of the phalanges at the metacarpophalangeal joints towards the medial (ulnar) side of the hand. It is usually associated with anterior (Volar) subluxation of the fingers (Figure 9.10). These deformities are characteristic but not pathognomonic of rheumatoid arthritis (Table 9.9).

TABLE 9.9 Differential diagnosis of a deforming polyarthropathy

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathy, particularly psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis or Reiter’s disease |

| Chronic tophaceous gout (rarely symmetrical) |

| Primary generalised osteoarthritis |

| Erosive or inflammatory osteoarthritis |

Next inspect the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints. Again note any skin changes and joint swelling. Look for the characteristic deformities of rheumatoid arthritis. These include swan neck and boutonnière deformity of the fingers and Z deformity of the thumb (Figure 9.10). They are due to joint destruction and tendon dysfunction. The swan neck deformity is hyperextension at the proximal interphalangeal joint and fixed flexion deformity at the distal interphalangeal joint. It is due to subluxation at the proximal interphalangeal joint and tendon shortening at the distal interphalangeal joint. The boutonnière (buttonhole) deformity consists of fixed flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint and extension of the distal interphalangeal joints. This is due to protrusion of the proximal interphalangeal joint through its ruptured extensor tendon. The Z deformity of the thumb consists of hyperextension of the interphalangeal joint and fixed flexion and subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joint.

Now look for the characteristic changes of osteoarthritis (Figure 9.11). Here the distal interphalangeal and first carpometacarpal joints are usually involved. Heberden’s nodese are a common deformity caused by marginal osteophytes that lie at the base of the distal phalanx. Less commonly, the proximal interphalangeal joints may be involved and osteophytes here are called Bouchard’sf nodes.

Now examine the nails. Characteristic psoriatic nail changes may be visible: these include pitting (small depressions in the nail), onycholysis (Figure 9.12) and, less commonly, hyperkeratosis (thickening of the nail), ridging and discoloration. The presence of vasculitic changes around the nailfolds implies active disease. These consist of black to brown 1–2 mm lesions due to skin infarction and occur typically in rheumatoid arthritis (Figure 9.13). Splinter haemorrhages may be present in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (and infective endocarditis) and are due to vasculitis. Unlike nailfold infarcts they are located under the nails in the nail beds. Periungual telangiectasiae occur in systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma or dermatomyositis.

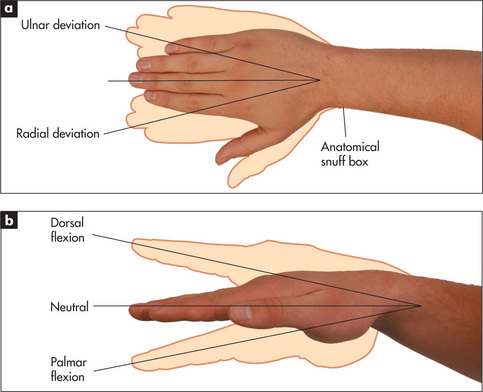

Feel and move

Turn the hands back again to the palm-down position. Palpate the wrists with both thumbs placed on the dorsal surface by the wrists, supported underneath by the index fingers (Figure 9.14). Feel gently for synovitis (boggy swelling) and effusions. The wrist should be gently dorsiflexed (normally possible to 75 degrees) and palmar flexed (also possible to 75 degrees) with the examiner’s thumbs. Then radial and ulnar deviation (20 degrees) is tested (Figure 9.15). Note any tenderness or limitation of movement or joint crepitus. Palpate the ulnar styloid for tenderness, which can occur in rheumatoid arthritis.

Test for tenderness at the tip of the radial styloid. This suggests de Quervain’sg tenosynovitis.

Feel for tenderness in the anatomical snuff box if scaphoid injury is suspected (Figure 9.15). Test for tenderness distal to the head of the ulna for extensor carpi ulnaris tendinitis.

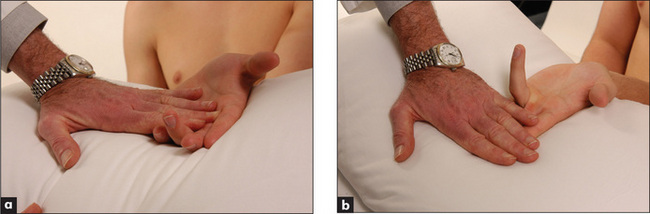

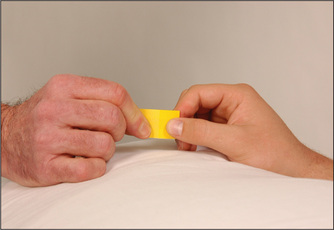

Go on now to the metacarpophalangeal joints, which are palpated in a similar way with the two thumbs. Again passive movement is tested. Volar subluxation can be demonstrated by flexing the metacarpophalangeal joint with the proximal phalanx held between the thumb and forefinger. The metacarpophalangeal joint is then rocked backwards and forwards (Figure 9.16). Very little movement occurs with this manoeuvre at a normal joint. Considerable movement may be present when ligamentous laxity or subluxation is present.

Palpate the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints for tenderness, swelling and osteophytes.

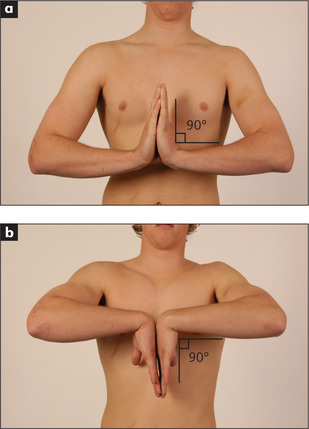

If the carpal tunnel syndrome is suspected, ask the patient to flex both wrists for 30 seconds—paraesthesiae will often be precipitated in the affected hand if the syndrome is present (Phalen’sh wrist flexion test). The paraesthesiae (pins and needles) are in the distribution of the median nerve (page 363), when thickening of the flexor retinaculum has entrapped the nerve in the carpal tunnel (Table 9.10). This test is more reliable than Tinel’s sign,i in which tapping over the flexor retinaculum (which lies at the proximal part of the palm) may cause similar paraesthesiae.4

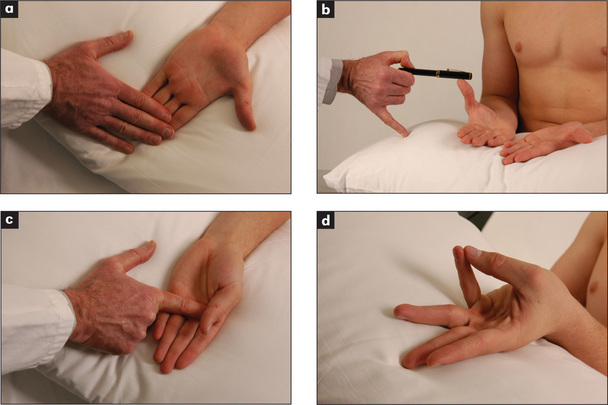

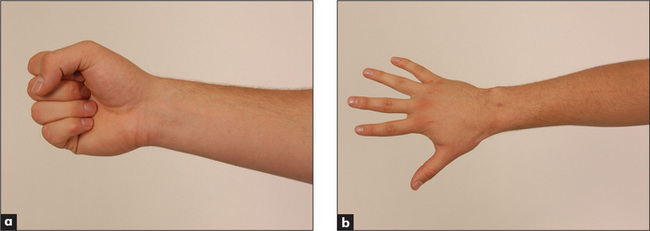

Now test active movements. First assess wrist flexion and extension as shown in Figure 9.17. Compare the two sides. Now go on to thumb movements (Figure 9.18). The patient holds the hand flat, palm upwards, and the examiner’s hand holds the patient’s fingers. Test extension by asking the patient to stretch the thumb outwards, abduction by asking for the thumb to be pointed straight upwards, adduction by asking him or her to squeeze the examiner’s finger, and opposition by getting the patient to touch the little finger with the thumb. Look for limitation of these movements and discomfort caused by them. Next test metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal movements. As a screening test, ask the patient to make a fist then to straighten out the fingers (Figure 9.19). Then test the fingers individually. If active flexion of one or more fingers is reduced, test the superficial and profundus flexor tendons (Figure 9.20). Hold the proximal finger joint extended and instruct the patient to bend it; the distal fingertip will flex if the flexor profundus is intact. Then hold the other fingers extended (to inactivate the profundus) and check finger flexion (inability indicates the superficialis is unable to work). The most common tendon ruptures are of the extensors of the fourth and fifth fingers.

Function

It is important to test the function of the hand. Grip strength is tested by getting the patient to squeeze two of the examiner’s fingers. Even an angry patient will rarely cause pain if given only two fingers. Serial measurements of grip strength can be made by asking the patient to squeeze a partly inflated sphygmomanometer cuff and noting the pressure reached. Key grip (Figure 9.21) is the grip with which a key is held between the pulps of the thumb and forefinger. Ask the patient to hold this grip tightly and try to open up his or her fingers. Opposition strength (Figure 9.22) is where the patient opposes the thumb and individual fingers. The difficulty with which these can be forced apart is assessed. Finally, a practical test, such as asking the patient to undo a button or write with a pen, should be performed.

Tests of hand function should be completed by formally assessing for neurological changes (page 362).

Examination of the hands is not complete without feeling for the subcutaneous nodules of rheumatoid arthritis near the elbows (Figure 9.23). These are 0.5–3 cm firm, shotty, non-tender lumps which occur typically over the olecranon. They may be attached to bone. They are found in rheumatoid-factor-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid nodules are areas of fibrinoid necrosis with a characteristic histological appearance and are probably initiated by a small vessel vasculitis. They are localised by trauma but can occur elsewhere, especially attached to tendons, over pressure areas in the hands or feet, in the lung, pleura, myocardium or vocal cords. The combination of arthritis and nodules suggests the diagnostic possibilities listed in Table 9.11.

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (rare) |

| Rheumatic fever (Jaccoud’s† arthritis) (very rare) |

| Granulomas—e.g. sarcoidosis (very rare) |

* Gouty tophi and xanthomata from hyperlipidaemia may cause confusion.

† François Jaccoud (1830–1913), professor of medicine, Geneva.

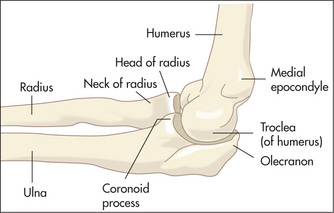

The elbows

Examination

Look for a joint effusion, which appears as a swelling on either side of the olecranon. Discrete swellings over the olecranon or over the proximal subcutaneous border of the ulna may be due to rheumatoid nodules, gouty tophi, an enlarged olecranon bursa or, rarely, to other types of nodules (Table 9.11).

Small amounts of fluid or synovitis of the elbow joint may be detected by the examiner, facing the patient, placing the thumb of the opposite hand along the edge of the ulnar shaft just distal to the olecranon where the synovium is closest to the surface. Full extension of the elbow joint will cause a palpable bulge in this area if fluid is present.

If lateral epicondylitis is suspected, ask the patient to extend the wrist actively against resistance (see Figure 9.70, page 291). Test the range of active movements by standing in front of the patient and demonstrating. If there is any deformity or complaint of numbness, a neurological examination of the hand and arm are indicated for ulnar nerve entrapment.

The shoulders

History

Pain is the most common symptom of a patient with shoulder problems.5 Typically it is felt over the front and lateral part of the joint. It may radiate to the insertion of the deltoid or even further. Pain felt over the top of the shoulder is more likely to come from the acromioclavicular joint or from the neck. Deformity has to be severe before it becomes obvious. Pain and stiffness may severely limit shoulder movement. Instability may cause the alarming feeling that the shoulder is jumping out of its socket. This is most likely to occur during abduction and external rotation (e.g. while attempting to serve a tennis ball). Loss of function may result in difficulty using the arms at above shoulder height or reaching around to the back.

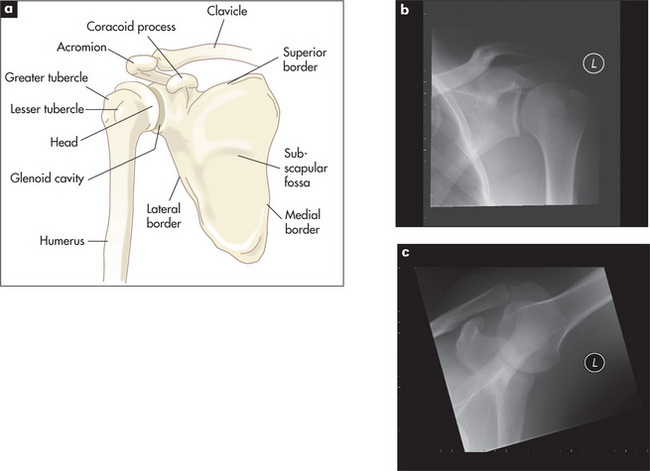

Examination

Feel for tenderness and swelling. Stand beside the patient, rest one hand on the shoulder and move the arm into different positions (see below). As the shoulder moves, feel the acromioclavicular joint and then move the hand along the clavicle to the sternoclavicular joint.

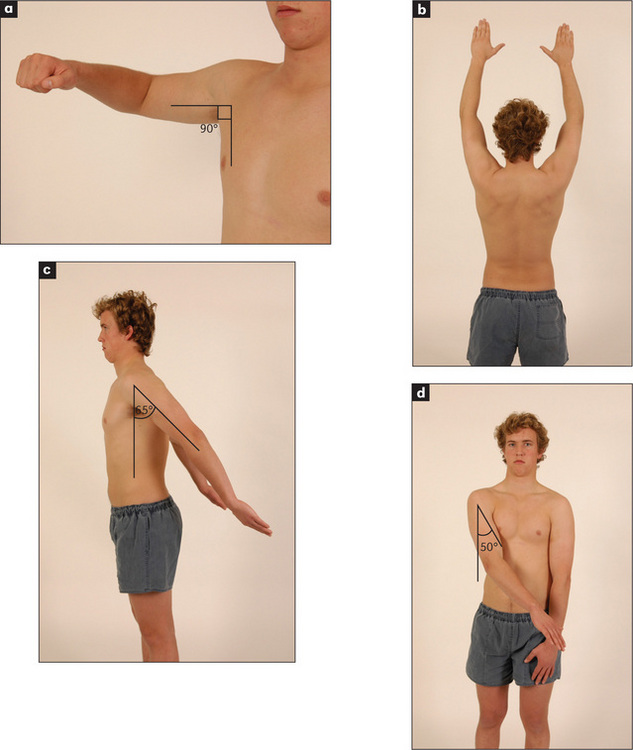

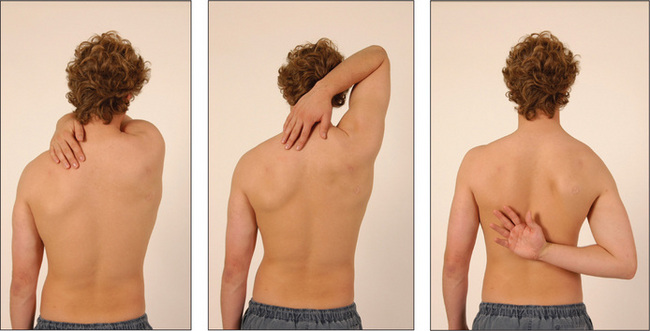

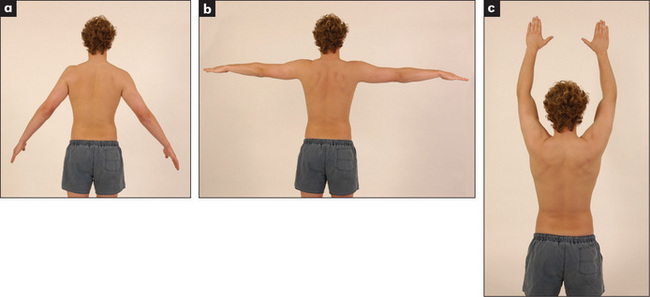

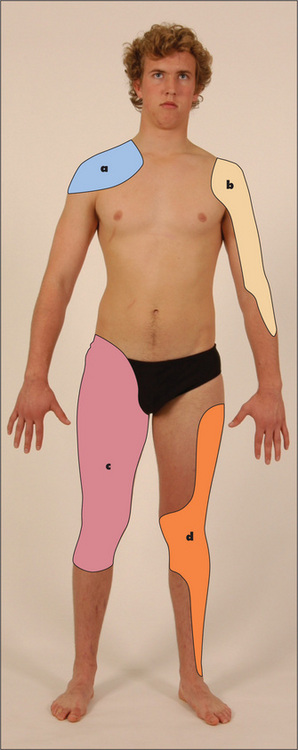

Move the joint (Figures 9.26 and 9.27). The zero position is with the arm hanging by the side of the body so that the palm faces forwards. Abduction tests glenohumeral abduction, which is normally possible to 90 degrees. For the right shoulder the examiner stands behind the patient resting the left hand on the patient’s shoulder, while the right hand abducts the elbow from the shoulder. Elevation is usually possible to 180 degrees when it is performed actively, as movement of the scapula is then included. Adduction is possible to 50 degrees. The arm is carried forwards across the front of the chest. External rotation is possible to 65 degrees. With the elbow bent to 90 degrees the arm is turned laterally as far as possible. Internal rotation is usually possible to 90 degrees. It is tested actively by asking the patient to place his or her hand behind the back and then to try to scratch the back as high up as possible with the thumb. Patients with rotator cuff problems complain of pain when they perform this manoeuvre. Flexion is possible to 180 degrees, of which the glenohumeral joint contributes about 90 degrees. Extension is possible to 65 degrees. The arm is swung backwards as in marching. During all these manoeuvres, limitation with or without pain and joint crepitus are assessed.

Figure 9.27 Examining the shoulder joint

(a) Extension. (b) Flexion. (c) Apprehension test. (d) Internal rotation and abduction.

Rapid assessment of shoulder movement is possible using the three-step ‘Apleyj scratch test’ (Figure 9.28). Stand behind and ask the patient to scratch an imaginary itch over the opposite scapula, first by reaching over the opposite shoulder, next by reaching behind the neck and finally by reaching behind the back.

The anterior stability of the shoulder joint is best assessed by the ‘apprehension’ test. Stand behind the patient, abduct, extend and externally rotate the shoulder (Figure 9.27c) while pushing the head of the humerus forwards with the thumb. The patient will strongly resist this manoeuvre if there is impending dislocation. There will be a similar response if the arm is adducted and internally rotated and posterior dislocation is about to occur.

The temporomandibular joints

Examination

Look in front of the ear for swelling. Feel by placing a finger just in front of the ear while the patient opens and shuts the mouth (Figure 9.29). The head of the mandible is palpable as it slides forwards when the jaw is opened. Clicking and grating may be felt. This is sometimes associated with tenderness if the joint is involved in an inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis may affect the temporomandibular joint.

The neck

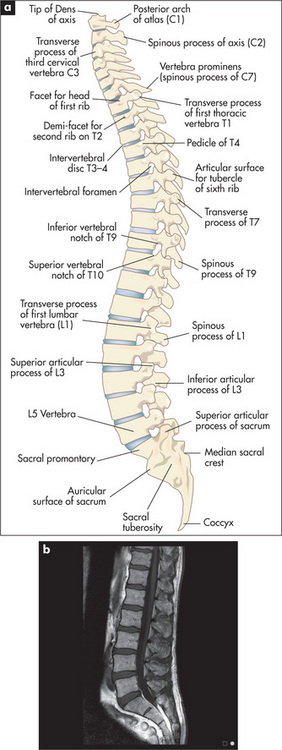

Examination anatomy—the spine

The spinal column (Figure 9.30) is like a tower of bones that protects the spinal cord and houses its blood supply and efferent and afferent nerves. It provides mechanical support for the body and is flexible enough to allow bending and twisting movements. There are diarthrodial joints between the articular processes of the vertebral bodies, and the vertebral bodies are separated by the vertebral discs. These pads of cartilage are flexible enough to allow movement between the vertebrae. In the cervical spine from C3 to C7, the uncovertebral joints of Luschkak are present. These are formed between a lateral bony extension (uncinate process) from the margin of the more inferior vertebral body with the one above. Osteoarthritic hypertrophy of these joints may result in pain or nerve root irritation.

History

The pain may have begun suddenly, suggesting a disc prolapse, or more gradually due to disc degeneration.

Examination

The patient should be undressed so as to expose the neck, shoulders and arms.

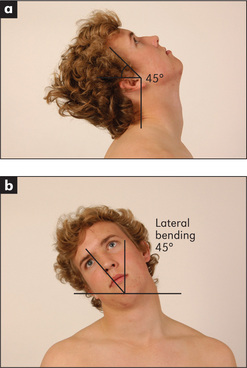

Look at the cervical spine while the patient is sitting up, and note particularly his or her posture (Figure 9.31). Movement should be tested actively. Flexion is tested by asking the patient to try to touch his or her chest with the chin (normal flexion is possible to 45 degrees). Extension (Figure 9.32a) is tested by asking the patient to look up and back (normally possible to 45 degrees). Lateral bending (Figure 9.32b) is tested by getting the patient to touch his or her shoulder with the ear; lateral bending is normally possible to 45 degrees. Rotation is tested by getting the patient to look over the shoulder to the right and then to the left. This is normally possible to 70 degrees.

Feel the posterior spinous processes. This is often easiest to do when the patient lies prone with the chest supported by a pillow and the neck slightly flexed. The examiner should feel for tenderness and uneven spacing of the spinous processes. Tenderness of the facet joints will be elicited by feeling a finger’s breadth lateral to the middle line on each side (Figure 9.33).

The thoracolumbar spine and sacroiliac joints

History

Lower back pain is a very common symptom (Table 9.12). The discomfort is usually worst in the lumbosacral area. Ask whether the onset was sudden and associated with lifting or straining or whether it was gradual.1,2 Stiffness and pain in the lower back that is worse in the morning is characteristic of an inflammatory spondyloarthropathy. Pain that shoots from the back into the buttock and thigh along the sciatic nerve distribution is called ‘sciatica’. In sciatic nerve compression at a lumbosacral nerve root, the pain is often aggravated by coughing or straining. ‘Lumbago’ however is often due to referred pain (e.g. from the vertebral joints). There may be other neurological symptoms in the legs due to nerve compression or irritation. The distribution of the paraesthesiae or weakness may indicate the level of spinal cord or nerve root abnormality. One should also ask about urinary incontinence and retention as well as numbness in the ‘saddle region’, erectile dysfunction and bowel incontinence, which can be a result of cauda equina involvement.

Examination

Feel each vertebral body for tenderness and palpate for muscle spasm.1

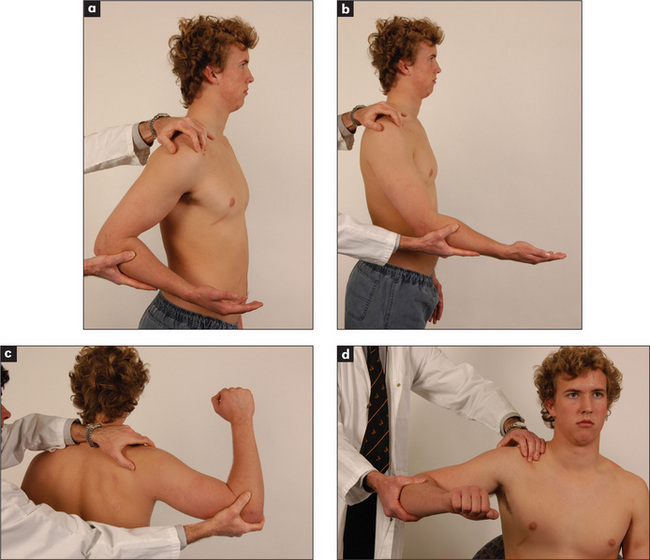

Movement is assessed actively. Bending movements largely take place at the lumbar spine, while rotational movements occur at the thoracic spine. Range of movement is tested by observation (Figure 9.34) and the use of Schober’s test (see below) (Figure 9.35).

Figure 9.34 Movements of the thoracolumbar spine

(a) Flexion. (b) Extension. (c) Lateral bending. (d) Rotation.

Figure 9.35 Schober’s test

From Douglas G, Nicol F and Robertson C, Macleod’s Clinical Examination, 12th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2009, with permission.

Measure the lumbar flexion with Schober’s test (Figure 9.35). A mark is made at the level of the posterior iliac spine on the vertebral column (approximately at L5). One finger is placed 5 cm below and another 10 cm above this mark. The patient is then asked to touch the toes. An increase of less than 5 cm in the distance between the two fingers indicates limitation of lumbar flexion. The finger-to-floor distance at full flexion can be measured serially to give an objective indication of disease progression.

Assess straight leg raising (Lasègue’sl test includes passive ankle dorsiflexion). With the patient lying down, lift the straightened leg if sciatica is suspected (normally to 80–90 degrees). This will be limited by pain in lumbar disc prolapse (less than 60 degrees).

Now get the patient to lie in bed on the stomach. Look for gluteal wasting. The sacroiliac joints lie deep to the dimples of Venus.m By tradition, firm palpation with both palms overlying each other is used to elicit tenderness in patients with sacroiliitis. Test each side separately.

The complete examination of the back also requires neurological assessment of the lower limbs.6

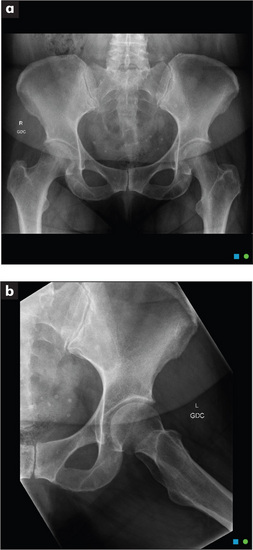

The hips

A history of a fall and inability to walk or bear weight on the leg suggests a fracture of the neck of the femur. A history of rheumatoid arthritis and pain which is present at rest suggests rheumatoid arthritis of the hip. Osteoarthritis is more likely to evolve gradually in older people and is associated with obesity and with recurrent trauma.

Ask about systemic symptoms such as fever and weight loss which might be a sign of septic arthritis.

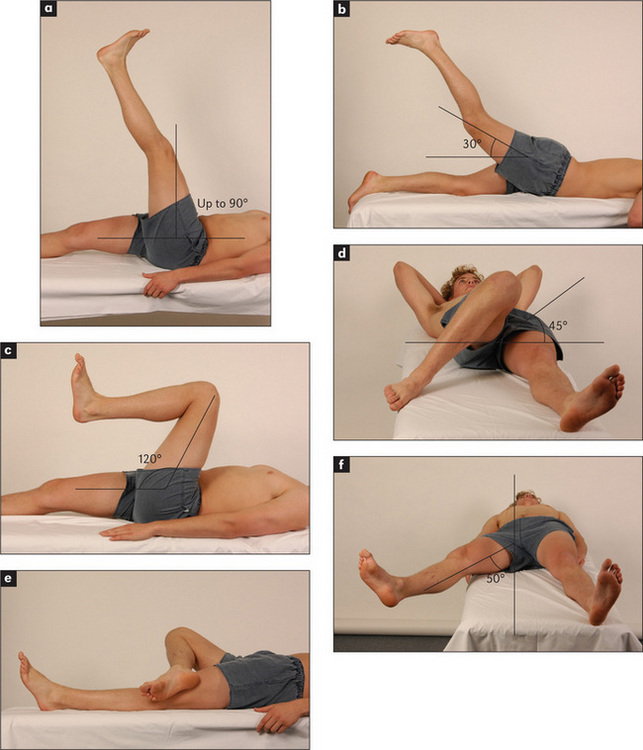

Examination

Get the patient to lie down, first on the back.

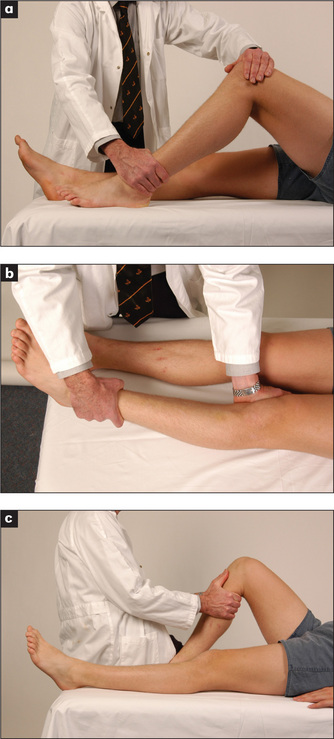

Move the hip joint passively (Figure 9.37). Flexion is tested by flexing the patient’s knee and moving the thigh towards the chest. The examiner keeps the pelvis on the bed by holding the other leg down. A fixed flexion deformity (inability to extend a joint normally) may be masked by the patient’s arching the back and tilting the pelvis forward and increasing lumbar lordosis unless Thomas’s testn is applied. The legs are fully flexed to straighten the pelvis. One leg is then extended. A fixed flexion deformity (e.g. as result of osteoarthritis) will prevent straightening. Rotation is tested with the knee and hip flexed. One hand holds the knee, the other the foot. The foot is then moved medially (external rotation of the hip, normally possible to 45 degrees), then laterally (internal rotation of the hip, normal to 45 degrees). Abduction is tested by standing on the same side of the bed as the leg to be tested. The right hand grasps the heel of the right leg while the left hand is placed over the anterior superior iliac spine to steady the pelvis. The leg is then moved outwards as far as possible. This is normally possible to 50 degrees. Adduction is the opposite. The leg is carried immediately in front of the other limb and this is normally possible to 45 degrees.

Ask the patient to roll over onto the stomach. Extension is then tested by placing one hand over the sacroiliac joint while the other elevates each leg. This is normally possible to about 30 degrees. Ask the patient to stand now and perform the Trendelenburgo test. The patient stands first on one leg and then on the other. Normally the non-weightbearing hip rises, but with proximal myopathy or hip joint disease the non-weightbearing side sags.

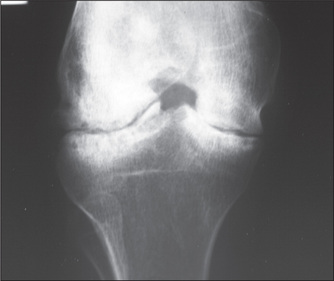

In patients with osteoarthritis of the joint, internal rotation, abduction and extension are usually restricted.7 Osteoarthritic joints (Figure 9.38) show loss of joint space, sclerosis (thickening and increased radiodensity) at the joint margins and osteophyte (bony outgrowth) formation on plain X-ray films.

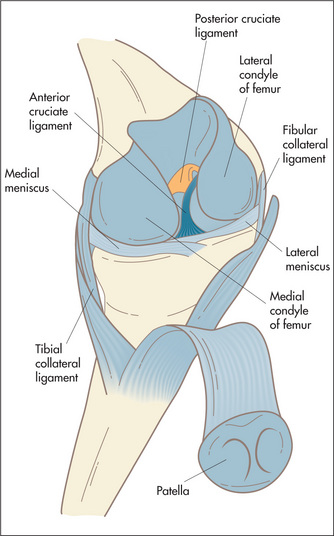

The knees

History (Table 9.14)

| Area of pain | Associated features |

| Lateral aspect of knee | |

| Tear of lateral meniscus | History of trauma |

| Locking or clicking | |

| Swelling delayed after injury | |

| Tear of lateral collateral ligament | Knee gives way |

| Biceps femoris strain | Overuse or injury |

| Medial aspect of knee | |

| Tear of medial meniscus | History of trauma |

| Locking or clicking | |

| Swelling delayed after injury | |

| Tear or strain of medial collateral ligament | Knee gives way |

| Hamstring strain | Overuse or injury |

| Patellofemoral syndrome | Overuse |

| Chronic symptoms | |

| Back of the knee | |

| Baker’s cyst | Sudden pain |

| Localised swelling and tenderness | |

| Bursitis, e.g. popliteal, semimembranosus | Overuse pattern |

| Chronic pain | |

| Hamstring strain | Injury or overuse |

| Deep venous thrombosis | |

| Front of the knee | |

| Patellar fracture | Injury |

| Sudden pain and tenderness | |

| Swelling | |

| Separation of fractured segments, visible or palpable | |

| Patellar tendinitis | Overuse |

| Osteoarthritis | Chronic pain |

| Worse with walking | |

| History of old injuries | |

| Prepatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee*) | Occupation |

| Infrapatellar bursitis (clergyman’s knee) | Occupation |

* Described by Henry Hamilton Bailey (1894–1961) as ‘the most elementary diagnosis in surgery’.

Osteoarthritis of the knee is very common. Older age, previous injury and stiffness lasting less than half an hour are in favour of this diagnosis as the cause of knee pain. Good signs guide 9.1 outlines the symptoms and signs of this condition. Physically active adolescents may present with pain and swelling below the knee at the point of attachment of the patellar tendon to the tibial tuberosity—tibial apophysitis or Osgood Schlatter’s disease.p This is the most common traction apophysitis.

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 9.1 Osteoarthritis as the cause of chronic knee pain

| Symptom or sign | LR positive | LR negative |

| Stiffness < 30 mins | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| Crepitus on passive movement | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| Bony enlargement | 11.8 | 0.5 |

| Palpable increase in temperature | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| Valgus deformity | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| Varus deformity | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| At least 3 of the above | 3.1 | 0.1 |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Examination

This is performed with the patient in a number of positions and, of course, walking.8,9 Even more than with the other joints, it is important to examine the more normal or uninjured knee first. This will help with the interpretation of changes in the other knee and give the patient more confidence that the examination will not be painful.

Feel the quadriceps for wasting. Palpate over the knees for warmth and synovial swelling.

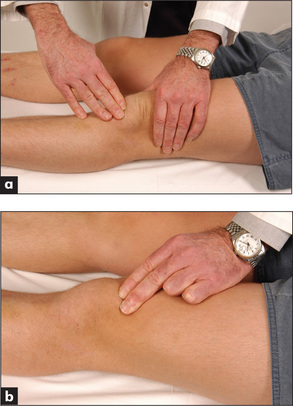

Test carefully for a joint effusion. The patellar tap is used to confirm the presence of large effusions (Figure 9.40). One hand rests over the lower part of the quadriceps muscle and compresses the suprapatellar extension of the joint space. The other hand pushes the patella downwards. The sign is positive if the patella is felt to sink and then comes to rest with a tap as it touches the underlying femur. The bulge sign is used to detect small effusions. Here the left hand compresses the suprapatellar pouch while the fingers of the right hand are run along the groove beside the patella on one side and then the other. A bulging along the groove due to a fluid wave, on the side not being compressed, is a sign of a small effusion.

Figure 9.40 Testing for patellar effusion

(a) The patellar tap. (b) The bulge sign: compressing the suprapatellar pouch.

Move the joint passively. Test flexion (normally possible to 135 degrees) and extension (normal to 5 degrees) by resting one hand on the knee cap while the other moves the leg up and down (Figure 9.41a). The range of movements and the presence of crepitus are noted. While holding the knee flexed, feel for and attempt to localise tenderness. Feel gently for tenderness along the joint line at the patellar ligament and at the sites of attachment of the collateral ligaments.

Figure 9.41 Knee examination

(a) Testing knee flexion. (b) Testing the collateral ligaments. (c) Testing the cruciate ligaments.

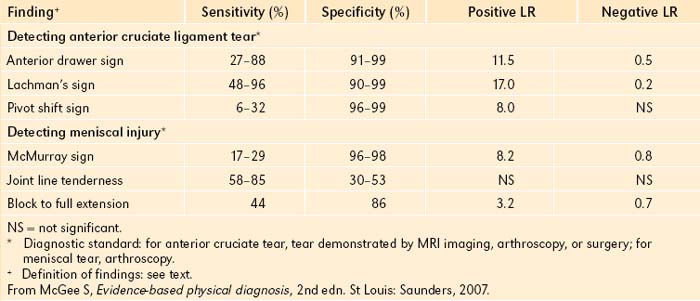

Test the ligaments next. The lateral and medial collateral ligaments are assessed by having the knee slightly flexed while holding the leg, with the examiner’s forearm resting along the length of the tibia; lateral and medial movements of the leg on the knee joint are tested (Figure 9.41b). Meanwhile the thigh is steadied with the other hand. Movements of more than 5–10 degrees are abnormal. The cruciate ligaments (Figure 9.41c) are tested next. The examiner steadies the patient’s foot with an elbow or by sitting on it. The patient’s knee is flexed to 90 degrees. The examiner’s hands grasp the tibia and attempt anterior and posterior movements of the leg on the knee joint. Movement may be detected by the examiner’s thumbs positioned at the joint margins. Again, movement of more than 5–10 degrees is abnormal. Increased anterior movement suggests anterior cruciate ligamentous laxity, and increased posterior movement suggests posterior cruciate ligamentous laxity. The Lachman test may be more accurate (positive LR 42.0, negative LR 0.1).8 Here the knee is flexed 20–30 degrees while the patient is lying supine. Grasp the femur (place your hand above the knee) to steady it, then grab the lower leg below the knee and give it a quick forward tug. It is abnormal when there is exaggerated anterior tibial movement or the knee fails to stop with a thud.

Ask the patient to roll into the prone position. Look and feel in the popliteal fossa for a Baker’s cyst.q This is a pressure diverticulum of the synovial membrane that occurs through a hiatus in the knee capsule (Figure 9.42). It is best seen with the knee extended. Rupture of this into the calf muscle produces signs that may mimic a deep venous thrombosis. Rupture is often associated with the ‘crescent sign’— ecchymoses below the malleoli of the ankle. A Baker’s cyst must be distinguished from an aneurysm of the popliteal artery, which will be pulsatile, and a bony tumour (very hard).

This is also the position in which Apley’s grinding test may be performed (Figure 9.43). This is a test of meniscal damage. The patient’s leg is flexed to 90 degrees, the examiner stabilises the thigh by kneeling lightly on it and while pressing on the foot rotates the leg backwards and forwards. Pain or clicking make the test positive. The distraction test is the opposite. Here the patient’s leg is pulled upwards so as to take the strain off the menisci and stretch the ligaments. If the patient finds the test painful, a ligamentous abnormality may be the cause.

McMurray’sr test (Figure 9.44) is another way of detecting a meniscal tear. The patient lies on the back, the examiner stands on the side to be tested and holds the ankle. The examiner’s other hand sits on the medial side of the knee and pushes to apply valgus force. The patient’s leg is then extended from the flexed position while being internally and then externally rotated. The test is positive if there is a popping sensation, which may be followed by inability to extend the knee.

Stand the patient up. Look particularly for varus (bow-leg) and valgus (knock-knee) deformity.

The ankles and feet

History

The usual symptom is pain. If this is present only when the patient wears shoes, the shoes rather than the feet may be the problem. There may be a specific area that is painful and the patient should be asked to point to this. There may be a history of injury or of intensive or unusual exercise. Ankle injuries are common in certain sports that involve twisting of the foot on the leg (e.g. netball, football) (Table 9.15). Rupture of the Achilles tendon occurs in squash and tennis players in patients over 50 and following forced dorsiflexion of the foot.

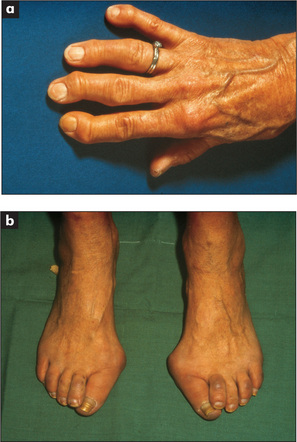

Patients with foot (Table 9.16) or ankle pain may have a history of rheumatoid arthritis. This can cause pain and deformity and affect the ankle subtalar, midtarsal and metatarsophalangeal joints.

TABLE 9.16 Differential diagnoses of foot pain

Very severe pain involving the first metatarsophalangeal joint is usually due to gout. Pain right over one of the metatarsals that comes on after unusually vigorous exercise may be due to a stress fracture.

Examination

This examination includes the ankles, feet and toes.

Look at the skin. Note any swelling, scars, deformity or muscle wasting. Deformities affecting the forefoot include hallux valgus (fixed lateral deviation of the main axis of the big toe), clawing (fixed flexion deformity) and crowding of the toes, as occurs in rheumatoid arthritis. Sausage deformities of the toes occur with psoriatic arthropathy or Reiter’ss disease (Figure 9.46). Look for the nail changes that suggest psoriasis. Inspect the transverse arch of the foot, which runs underneath the metatarsophalangeal joints, and the longitudinal arch, which runs from the first metatarsophalangeal joint to the heel. These arches, which bear the weight of the body, may be flattened in arthritic conditions of the foot like rheumatoid arthritis. Calluses over the metatarsal heads on the plantar surface of the foot occur with subluxation of these joints (Figure 9.47).

Feel, starting with the ankle, for swelling around the lateral and medial malleoli. This should not be confused with pitting oedema. If an ankle fracture is suspected because of a history of injury, tenderness over the posterior medial malleolus is a reliable sign (positive LR 4.8).10

With the subtalar joint, only inversion and eversion of the foot on the ankle are tested. Pain on movement is more important than range at this joint. The midtarsal (midfoot) joint allows rotation of the forefoot when the hindfoot is fixed. This is done by steadying the ankle with one hand and rotating (twisting) the forefoot. Again, pain on motion rather than loss of range of movement is noted.

Squeeze the metatarsophalangeal joints by compressing the first and fifth metatarsals between your thumb and forefinger. Tenderness suggests inflammation, common in early rheumatoid arthritis. Press upwards from the sole of the foot just proximal to the metatarsophalangeal joints of the third and fourth toes. Pain here suggests Morton’st neuroma. This is due to entrapment and swelling of the digital nerve between the toes. It is associated with pain and numbness of the sides of these toes.

Palpate the Achilles tendon for rheumatoid nodules (Figure 9.48) and tenderness due to Achilles tendinitis. An old Achilles tendon rupture may be detected by squeezing the calf: normally the foot plantar flexes unless the tendon has previously ruptured (Simmonds’u test). Also palpate the inferior aspect of the heel for tenderness; this may indicate plantar fasciitis, which occurs in the seronegative spondyloarthropathies and sometimes for no apparent reason.

Correlation of physical signs and rheumatological disease

Rheumatoid arthritis (Figures 9.30 and 9.49)

Figure 9.49 Rheumatoid arthritis

To examine the patient with suspected rheumatoid arthritis, sit him or her up in bed or on a chair.

General inspection

Look to see whether the patient has a Cushingoid appearance due to steroid treatment (page 309), or whether there are signs of weight loss that may indicate active disease.

The hands

Put the hands on a pillow. Look especially for symmetrical small joint synovitis (the distal interphalangeal joints are usually spared). The other common abnormalities are ulnar deviation, volar subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joints, and Z deformity of the thumb with swan neck and boutonnière deformity of the fingers. Examine the fingernails and periungual areas for splinter-like vasculitic changes and look for wasting of the small muscles of the hand. Look at the palms for palmar erythema. Feel the palms for palmar tendon crepitus while the patient extends and flexes the fingers. Look for signs of an ulnar nerve palsy (from ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow) and a median nerve palsy (carpal tunnel).

The eyes

Look at the eyes for redness which may indicate the dryness of Sjögren’s syndrome (Table 9.8), which occurs in 10%–15% of cases. Note also nodular scleritis (an elevated white or purple-red lesion, which is pathologically a rheumatoid nodule and usually appears surrounded by the intense redness of the injected sclera) (Figure 9.50). These nodules occur especially in the superior parts of the sclera and are often bilateral, but affect only 1% of patients. Iritis does not occur.

With severe scleritis, scleral thinning may occur, exposing the underlying choroid. This is called scleromalacia. Look for cataracts due to steroid treatment. Conjunctival pallor may be present, indicating anaemia due to iron deficiency. This can be a result of blood loss from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, folate deficiency from a poor diet, hypersplenism or chronic inflammation, or some combination of these.

The temporomandibular joints

Feel the temporomandibular joints for crepitus as the patient opens and shuts the mouth.

The chest

Now examine the lungs for signs of pleural effusions or pulmonary fibrosis. Caplan’s syndromev is the presence of rheumatoid lung nodules in combination with pneumoconiosis.

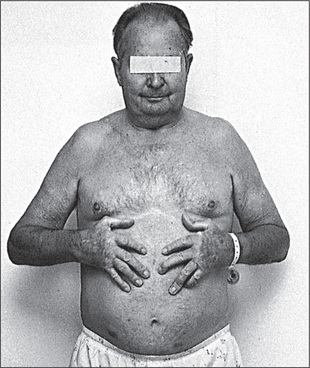

The abdomen

Feel the abdomen for splenomegaly (this occurs in up to 10% of patients and suggests the possibility of Felty’s syndrome, page 229) and hepatomegaly. Feel the inguinal lymph nodes.

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies

Ankylosing spondylitis

The following areas should be examined.

The legs: Achilles tendinitis; plantar fasciitis; signs of cauda equina compression (rare)—lower limb weakness, loss of sphincter control, saddle sensory loss.

The lungs: decreased chest expansion (less than 5 cm); signs of apical fibrosis.

The heart: signs of aortic regurgitation.

The eyes: acute iritis (tends to recur)—painful red eye (10%–15%) (Figure 9.51).

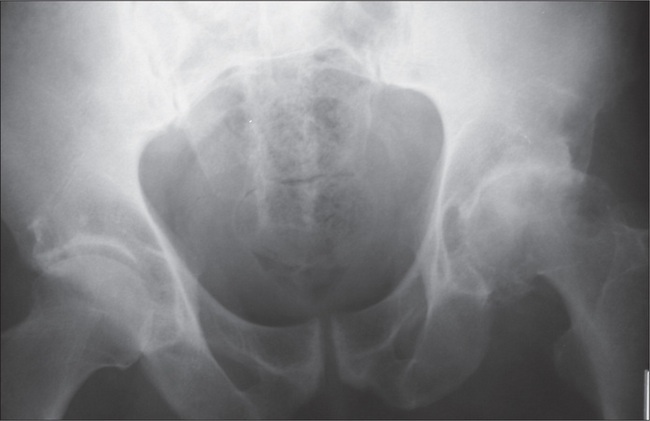

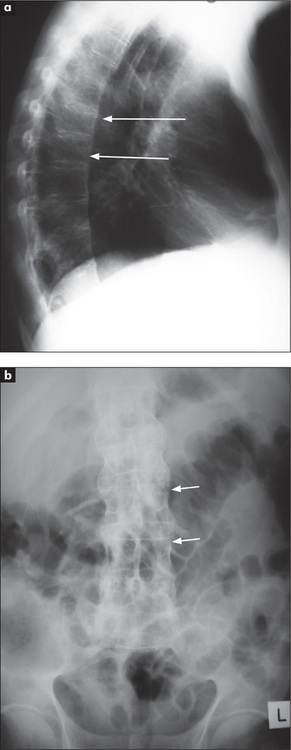

X-rays of the spine and sacroiliac joints (Figure 9.52): may show ankylosis (fusion) of the sacroiliac joints and ‘squaring’ of the vertebral bodies as a result of loss of their anterior corners and periostitis of their waists. ‘Bridging syndesmophytes’w occur as a result of ossification of the fibres of the joint annulus. Severe disease causes the changes called bamboo spine visible on X-ray.

Reiter’s syndrome (reactive arthritis)

The genital region: urethral discharge; circinate balanitis—scaly, superficial reddened erosions with well-demarcated borders on the glans penis (Figure 9.53).

The eyes: conjunctivitis; iritis (rare).

The mouth: painless smooth mucosal lesions, especially of the tongue.

The back: sacroiliac joints (may be unilaterally involved).

The lower limbs (more commonly affected): knees, ankles; metatarsophalangeal joints and toes (‘sausage toes’); plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis; keratoderma blennorrhagica on the sole (non-tender reddish-brown macules, which become scaling papules; Figure 9.54)—this is indistinguishable from pustular psoriasis; nails thickened, opaque and brittle.

Figure 9.54 Reiter’s syndrome with keratoderma blennorrhagica

From FS McDonald, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Cardiovascular system: aortic regurgitation (rare).

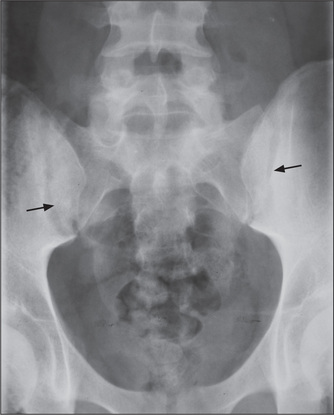

X-ray findings: the first attack of arthritis is associated with soft-tissue changes and subsequent attacks may lead to joint-space narrowing and proliferative erosions at the joint margins. Changes in the sacroiliac joints and spine resemble those of ankylosing spondylitis except that the sacroiliac joint changes and spinal syndesmophytes tend to be asymmetrical. Calcaneal spurs (Figure 9.55)—a result of plantar fasciitis—are characteristic.

Psoriatic arthritis

Ten per cent of patients with psoriasis (page 446) have arthritis.

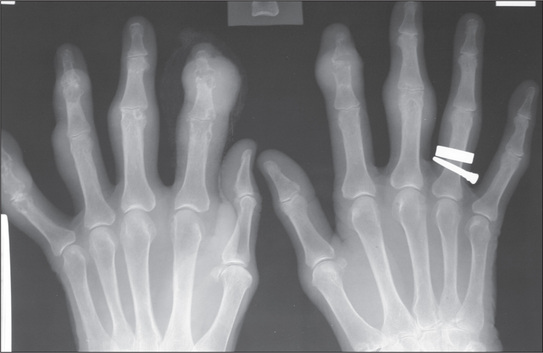

X-ray findings (Figure 9.56): in mild cases X-rays are normal or show only joint-space narrowing and erosive changes. Unlike the X-rays of rheumatoid joints the bone density is maintained and there may be sclerotic changes in the small bones. Ankylosis of peripheral joints and arthritis mutilans can occur in either condition. The involvement of the spine and sacroiliac joints is asymmetrical, as in Reiter’s syndrome.

Gouty arthritis

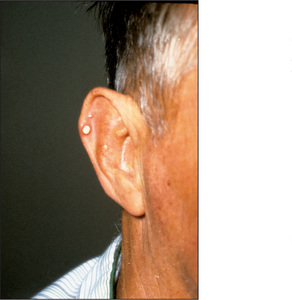

Begin with the feet, as acute gouty arthritis affects the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe in 75% of cases. Next examine the ankles and knees, which tend to be involved after recurrent attacks. The fingers, wrists and elbows are affected late (Figure 9.57). Inspect and palpate for gouty tophi (these are urate deposits with inflammatory cells surrounding them) (Latin tophus, ‘chalk stone’). The presence of tophi indicates chronic recurrent gout. They tend to occur over the joint synovia, the olecranon bursa, the extensor surface of the forearm, the helix of the ear (Figure 9.58), and in the infrapatellar and Achilles tendons.

Finally, examine for signs of the causes of secondary gout: increased purine turnover due to myeloproliferative disease (page 236), lymphoma (page 237) or leukaemia; and decreased renal urate excretion due to renal disease or hypothyroidism. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus and ischaemic heart disease are more common among sufferers of gout.

X-rays (Figure 9.59) show multiple juxta-articular erosions which may obliterate the joint space.

Calcium pyrophosphate arthropathy (pseudogout)

This may present a similar picture to that described above for true gout, but usually large joints (especially the knees) and wrists are involved. In a minority of patients there will be signs of hyperparathyroidism, haemochromatosis or true gout.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

This is a multisystemic chronic inflammatory disease of unknown origin, named because the erosive nature of the condition was likened to the damage caused by a hungry wolf (Latin lupusx ‘wolf’) (Figure 9.60).

Forearms

Livedo reticularis may occur here; in Latin this describes skin discoloration in the form of a small net. This is formed by connected bluish-purple streaks without discrete borders. They occur usually on the limbs and are associated with various connective tissue diseases.11 Look for purpura (due to vasculitis12 or autoimmune thrombocytopenia). Examine for a proximal myopathy (due to the disease itself or to steroid treatment). Subcutaneous nodules very rarely occur in SLE. The axillary nodes may be enlarged but will not be tender.

The head and neck

Examine the eyes for scleritis and episcleritis (see Figure 9.50). The eyes may be red and dry (Sjögren’s syndrome). Pallor of the conjunctivae occurs with anaemia, usually due to chronic disease. Occasionally jaundice due to autoimmune haemolytic anaemia may be found. Perform a fundoscopy for cytoid bodies, which are hard exudates (white spots) due to aggregates of swollen nerve fibres and are secondary to vasculitis.

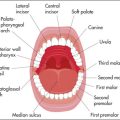

A facial rash may be diagnostic (Figure 9.61). The classical rash is an erythematous ‘butterfly rash’ over the cheeks and bridge of the nose and must be distinguished from rosacea. Mouth ulcers on the soft or hard palate may occur and the mouth may be dry (Sjögren’s syndrome).

After examining the face, feel for cervical lymphadenopathy, which is usually non-tender.

The legs

Examine for proximal myopathy and peripheral neuropathy (mainly sensory).

Rarely there may be signs of hemiplegia, cerebellar ataxia or chorea.

Leg ulceration over the malleoli, due to vasculitis or the antiphospholipid syndrome,11 is important. Very occasionally the toes may be gangrenous. There may be ankle oedema from the nephrotic syndrome or fluid retention from steroids. Livedo reticularis may be present on the legs.

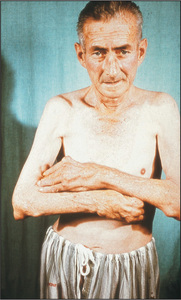

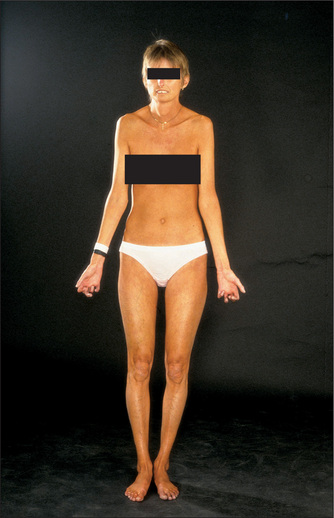

Scleroderma (progressive systemic sclerosis)

General inspection (Figure 9.62)

Look for cachexia due to dysphagia (from an oesophageal motility disturbance) or malabsorption (due to bacterial overgrowth).

Skin changes in scleroderma vary. There may be an early oedematous phase with non-tender pitting oedema of the hands which appear tightly swollen. In patients with progressive disease the oedematous skin is replaced by indurated skin which appears thickened, hard and tight. This phase usually begins in the fingers (Table 9.17).

TABLE 9.17 Differential diagnosis of thickened tethered skin

| Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), diffuse type; milder changes in limited cutaneous scleroderma |

| Mixed connective tissue disease (a distinct disorder with features of scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and myositis) |

| Eosinophilic fasciitis—widespread skin thickening due to inflammation of the fascia often following excessive muscle exercise; occurs in association with eosinophilia and hypergammaglobulinaemia |

| Localised morphea—heterogeneous group of disorders where there are small areas of sclerosis: most common type is morphea, which begins with large plaques of red or purple skin that evolve into sclerotic areas and may regress spontaneously over years |

| Chemically induced: vinyl chloride, pentazocine, bleomycin |

| Pseudoscleroderma: porphyria cutanea tarda, acromegaly, carcinoid syndrome |

| Scleroedema: thickened skin over the shoulders and upper back in diabetes mellitus |

| Graft versus host disease |

| Silicosis |

| Eosinophilic myalgia syndrome (L-tryptophan) |

| Toxic oil syndrome |

The hands

Examine the hands. Note particularly calcinosis (palpable nodules due to calcific deposits in the subcutaneous tissue of the fingers), Raynaud’s phenomenon sometimes causing atrophy of the finger pulps (due to ischaemia) (Figure 9.63), sclerodactyly (tightening of the skin of the fingers leading to tapering), and multiple large telangiectasia on the fingers (Figure 9.64).

Look for contraction deformity of the fingers, which is relatively common (Figure 9.65), and for synovitis, although this is uncommon. The nails can be affected by Raynaud’s. It can be useful to inspect the nailfolds using a hand-held magnifying glass: in scleroderma you may see dilated capillary loops but this is not diagnostic. These are best viewed on the fourth digit. Assessing hand function is important in this disease.

The face

The skin of the face is involved in progressive disease. There is loss of normal wrinkles and skinfolds as well as of the eyebrows. The face appears pinched and expressionless (‘bird-like’ facies). Inspect for malar telangiectasia and look for salt-and-pepper pigmentation. Ask the patient to close the eyes—skin tethering may make this incomplete. The eyes may be dry (Sjögren’s syndrome), though this is uncommon, and the conjunctivae pale (there are a number of reasons for anaemia, including the presence of chronic disease, bleeding from oesophagitis, watermelon stomach and microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia).

The legs

Look for signs of vasculitis, ulceration and skin involvement. Peripheral neuropathy is rare.

Rheumatic fever

This is an inflammatory disease which is a delayed sequel to infection with group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus; it is uncommon in Western nations today. It is diagnosed by finding two major or one major and two minor criteria, plus evidence of recent streptococcal infection.

Major criteria: (i) carditis (causing tachycardia, murmurs, cardiac failure, pericarditis); (ii) polyarthritis; (iii) chorea (page 399); (iv) erythema marginatum (see below); (v) subcutaneous nodules (painless mobile swellings).

The vasculitides

This is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterised by inflammation and damage to blood vessels.12 The clinical features and major vessels involved are shown in Table 9.18.

| Name | Vessels | Characteristics |

| Small vessel vasculitis | ||

| Wegener’s* granulomatosis | Small to medium-sized capillaries, venules, arterioles, small arteries | Granulomatous inflammation affecting the respiratory tract, often with necrotising glomerulonephritis |

| Saddle-nose deformity | ||

| Churg-Strauss syndrome | Small | Asthma, eosinophilia, skin nodules, mononeuritis multiplex, pulmonary infiltrates |

| Henoch-Schonlein purpura | Small | Children affected; purpura over buttocks, abdominal pain, arthritis of knee and ankle, nephritis (40%) |

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Small | Glomerulonephritis, alveolar haemorrhage, neuropathy, pleural effusions |

| Mixed essential cryoglobulinaemia | Small | Arthritis, palpable purpura of extremities, Raynaud’s disease, neuropathy |

| Hepatitis C common | ||

| Medium-sized vessel vasculitis | ||

| Polyarteritis nodosa | Medium-sized to small | Myalgia, arthralgia, fever, palpable purpura, skin ulceration or infarction, weight loss, testicular tenderness, neuropathy (involvement of vasa nervorum), hypertension, renal infarction |

| Hepatitis B associated | ||

| Kawasaki’s disease | Medium-sized (coronary artery involvement) | Children affected; desquamating rash over extremities, strawberry tongue |

| Large vessel vasculitis | ||

| Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) | Medium to large (temporal and ophthalmic arteries and their branches) | Localised headache, systemic symptoms, tenderness temporal artery, jaw pain, visual loss—posterior ciliary artery (age ≥50 years) |

| Takayasu’s disease† | Large (aorta, brachial, carotid, ulnar and axillary arteries) | Systemic symptoms, claudication, loss of pulses (typically Asian race ≤40 years) |

GIT = gastrointestinal tract. SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus. PAN = polyarteritis nodosa. CNS = central nervous system.

* Frederich Wegener, German pathologist, described this in 1936.

† Mikito Takayasu (1860–1938), Japanese professor of ophthalmology.

Soft-tissue rheumatism

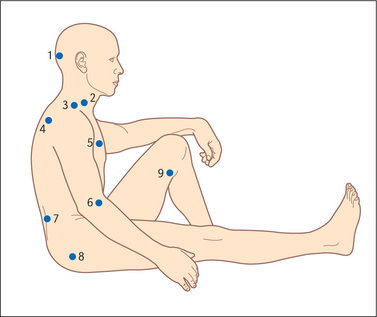

Fibromyalgia syndrome

Examination

Test for the characteristic multiple hyperalgesic tender points (Figure 9.66). These areas may be tender to finger pressure in normal people but in affected patients there is marked tenderness and a definite withdrawal response. This response should be obtained in at least 11 of 18 sites in the upper and lower limbs and on both sides (i.e. it is widespread and symmetrical). Next examine for hyperalgesia at control sites such as the forehead or distal forearm, where it should be absent.

Shoulder syndromes

Soft-tissue disorders of the shoulder are common and have certain particular clinical features.

Rotator cuff syndrome

Examination

Examine the shoulder joint. Note pain on abduction of the arm (Figure 9.67), with a painful arc of movement between 60 and 120 degrees of abduction. Involvement of other rotator cuff tendons causes similar painful movement. Biceps tendinitis is present in the majority of patients with a rotator cuff syndrome. Yergason’sy sign for biceps tendinitis is helpful (positive LR 2.8).10 The patient flexes the elbow to 90 degrees and pronates the wrist. The examiner holds the wrists and attempts to prevent the patient’s attempts to supinate the forearm. Inflammation of the head of the biceps causes pain in the shoulder since this muscle is the main supinator of the forearm.

Elbow epicondylitis (tennis and golfer’s elbow)

Many contact and non-contact sports can cause physical injury, although serious injuries are rather uncommon with certain sports (e.g. synchronised swimming). There may be pain over the epicondyles of the elbow. The lateral epicondyle is the most often affected and is called ‘tennis elbow’. Pain arises from the site of insertion of the extensor muscle tendons into the lateral epicondyle (enthesis). Involvement of the medial epicondyle at the site of insertion of the flexor tendons of the forearm causes medial epicondylitis—‘golfer’s elbow’. These conditions are also common in manual workers such as painters.

Examination

Examine for local tenderness over the lateral (Figure 9.68) or medial epicondyle (Figure 9.69). Ask the patient to extend the fingers against resistance (Figure 9.70). This will make the pain of lateral epicondylitis worse. Ask the patient to flex the fingers against resistance. This will exacerbate the pain of medial epicondylitis.

Tenosynovitis of the wrist

Inflammation of the synovial tubes in which tendons run can occur in patients with rheumatoid arthritis but also in otherwise healthy people. The cause is often unaccustomed repetitive movement. A common site for tenosynovitis is at the wrist, where it involves the long extensor and abductor tendons of the thumb (de Quervain’s tenosynovitis; Figure 9.71).

Examination

This reveals tenderness and swelling on the radial side of the wrist (radial styloid). There is pain on active or passive movement of the thumb. Confirm the diagnosis by performing Finkelstein’s test.z Hold the patient’s hand with the thumb tucked into the palm and then quickly turn the wrist into full ulnar deviation (Figure 9.72). An alternative approach that is reported to produce fewer false-positives involves gripping the patient’s thumb rather than tucking the thumb into the palm.13 Sharp pain will occur in the tendon sheath when the test is positive. Examine also the other common sites of tendon involvement—the flexor tendons of the fingers and the Achilles tendon.

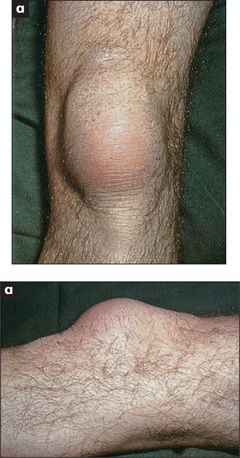

Bursitis

Bursae are found in areas exposed to mechanical strain or trauma, either at the site where muscle or tendon glides over bone or muscle, or superficially where bony prominences are exposed to mechanical stress. Bursitis usually occurs as a local soft-tissue inflammatory reaction to unusual mechanical pressure. It may be associated with rheumatoid arthritis, gout or sepsis. Common sites include the prepatellar area (housemaid’s knee) (Figure 9.73), over the olecranon (olecranon bursitis) and over the greater trochanter (trochanteric bursitis).

Nerve entrapment syndromes

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Compression of the median nerve at the wrist is the most frequent form. This seems hardly surprising when one remembers that the carpal tunnel, sandwiched between the carpal bones and the carpal ligament, contains 9 flexor tendons as well as the median nerve. These patients complain of numbness and paraesthesiae in the median nerve distribution (the 3 radial fingers and the radial side of the ring finger). Symptoms often wake patients from sleep and may radiate up the forearm (one-third of cases). The commonest cause is an overuse tenosynovitis of the flexor tendon sheaths at the wrist. Fluid retention during pregnancy or from use of the oral contraceptive pill can also produce carpal tunnel symptoms. In addition, median nerve compression can occur in rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, acromegaly and amyloidosis.

Examination

Symptoms can be reproduced by gentle percussion over the carpal tunnel while the wrist is held in extension (Tinel’s sign). This sign is negative in up to 30% of patients with electrophysiologically proven median nerve compression. Prolonged (60 seconds) passive wrist flexion (Phalen’s test) has a lower false-negative rate (positive LR 1.3, negative LR 0.7).10 Look for wasting in the median nerve distribution, and loss of motor (thenar muscle strength: weak thumb abduction) and sensory function. These signs occur only in advanced cases.

Meralgiaaa paraesthetica

Compression of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh causes paraesthesiae and sensory loss over the lateral side of the thigh (page 375). This entirely sensory nerve passes through the lateral part of the inguinal ligament only just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. Here it is subject to compression in patients who are obese, wear tight or heavy belts or spend long periods sitting. Diabetes, pregnancy and trauma can also be causes of problems with the nerve.

Morton’s ‘neuroma’

Metatarsalgia is a non-localised ache that spreads across the forefoot involving the area of some or all of the metatarsal heads. It can occur in normal feet after prolonged standing but also occurs in a number of other foot conditions (Table 9.19), and is often associated with poor-fitting shoes. Morton’s metatarsalgia is interdigital nerve entrapment (usually between the third and fourth metatarsal bones. Patients describe burning pain between the metatarsal bones and may have numbness on the adjacent toes. They get relief by removing their shoes and massaging the foot.

| Tight or pointed shoes |

| Atrophy of metatarsal fat pad in elderly people |

| Plantar calluses |

| Metatarsophalangeal joint arthritis |

| Flat or cavus foot deformity |

| Overlapping toes |

| Interdigital entrapment |

| Hemiplegia |

| Peripheral vascular disease |

1. Van den Hoogen H.M.M., Koes B.W., Van Eijk J.T.M., Bouter L.M. On the accuracy of history, physical, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate in diagnosing low back pain in general practice: a criteria based review of the literature. Spine. 1995;20:318-327. Unfortunately, distinguishing mechanical from non-mechanical causes of low back pain such as ankylosing spondylitis is clinically difficult. However, tenderness to pressure over the anterior superior iliac spines and over the lower sacrum may, based on other studies, be somewhat helpful for the positive diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis

2. Deyo R.A., Rainville J., Kent D.L. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? JAMA. 1992;268:760-765.

3. Fuchs H.A. Joint counts and physical measures. Rheum Dis Clin Nth Am. 1995;21:429-444. Describes useful quantitative methods to evaluate tenderness, pain on motion, swelling, deformity and limitation of movement

4. Katz J.N., Larson M.E., Sabra A., et al. The carpal syndrome: diagnostic utility of the history and physical examination findings. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:321-327. This study compares the neurophysiological assessment of the carpal tunnel syndrome with the information obtained by examination and history. No single symptom or sign is sufficiently predictive

5. Glockner S.M. Shoulder pain: a diagnostic dilemma. Am Fam Phys. 51, 1995. 1677-1687, 1690-1692. Reviews the utility of symptoms and signs in differential diagnosis

6. Katz J.N., Dalgas M., Stucki G., et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and physical examination. Arth Rheum. 1995;38:1236-1241. Describes symptoms (severe lower limb pain which is absent when the patient is seated) and signs (including a wide-based gait, positive Romberg’s sign, thigh pain with lumbar extension) that help predict this rare condition in older patients

7. Murtagh J. Diagnosis of early osteoarthritis of the hip joint: the four-step stress test. Aust Fam Phys. 1990;19:389. Discusses the diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the hip in a systematic way, suggesting a four-step approach

8. Solomon D.H., Simel D.L., Bates D.W., et al. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

9. Scholten R.J., Opstetten W., vander Plas C.G., et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

10. McGee S. Evidence-based clinical diagnosis, 2nd edn. Phildelphia: Saunders; 2007.

11. Grob J.J., Bonerandi J.J. Cutaneous manifestations associated with the presence of the lupus-anticoagulant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:211-219. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome can be associated with leg ulcers (that resemble pyoderma gangrenosum), livedo reticularis and fingertip ischaemia

12. Stevens G.L., Adelman H.M., Wallach P.M. Palpable purpura: an algorithmic approach. Am Fam Phys. 1995;52:1355-1362.

13. Elliott B.G. Finkelstein’s test: a descriptive error that can produce a false-positive. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:481-482. Careful explanation of the performance of this test (which is often misunderstood) appears in this article. Movement with the thumb folded into the hand can produce a false-positive result

Hochberg M., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., Weinblatt M.E., Weisman M.H. Rheumatology, 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Snaith M.L. ABC of rheumatology, 3rd edn. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2004.

Solomon L., Nayagam D., Warwiak D. Apley’s system of orthopaedics and fractures, 9th edn. London: Butterworth-Heineman; 2009.

a Maurice Raynaud (1834–1881) described this in his first work, published in Paris in 1862.

b Halushi Behçet (1889–1948), Turkish dermatologist.

c The traditional treatment, striking the lesion very hard with the family Bible, is not effective.

d Jean Martin Charcot (1825–1893), Parisian physician and neurologist. He became professor of nervous diseases, holding the first Chair of Neurology in the world. His pupils included Babinski, Marie and Freud.

e William Heberden (1710–1801), London physician, and doctor to George III and Samuel Johnson, described these in 1802. He was the first person to describe angina.

f Charles Jacques Bouchard (1837–1915), Parisian physician.

g Fritz de Quervain (1868–1940), professor of surgery in Berne, Switzerland.

h George Phalen, orthopaedic surgeon, the Cleveland Clinic.

i Jules Tinel (1879–1952), physician and neurologist in Paris. In 1915 he described tingling in the distribution of a nerve that had been severed and was regrowing when it was percussed.

j Alan Apley, orthopaedic surgeon, St Thomas’s Hospital, London.

k Hubert von Luschka (1820–75), professor of anatomy in Tübingen.

l Charles E Lasègue (1816–83), Professor of Medicine in Paris and pupil of Trousseau.

m Roman goddess of love—her ancient Greek equivalent was Aphrodite.

n Hugh Thomas (1834–91), ‘the father of orthopaedic surgery’, worked in Liverpool as a bone-setter but did not have a hospital appointment.

o Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844–1924), professor of surgery at Rostock, Bonn and Leipzig.

p Robert Osgood (1873–1956). He worked in France during the First World War and then at the Massachusetts General Hospital where he founded the X-ray department and subsequently developed several radiation-induced skin tumours.arl Schlatter (1864–1934), professor of surgery in Zurich. He pioneered a total gastrectomy operation in 1897.

q William Baker (1839–96), surgeon at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, described this in 1877.

r Thomas McMurray (1888–1949), the first professor of orthopaedic surgery in Liverpool.

s Hans Reiter (1881–1969), professor of hygiene in Berlin, described the syndrome in 1916. This was well before he became an enthusiastic Nazi.

t Thomas Morton (1835–1903), general and eye surgeon, Philadelphia Hospital, performed one of the first appendicectomies.

u Franklin Simmonds, orthopaedic surgeon, Rowley Bristow Hospital, Surrey, UK; he is now retired.

v Anthony Caplan, Welsh physician, described this in 1953.

w A syndesmosis is a joint where the bones are joined by fibrous ligaments or sheets.

x Lupus has been used as a name for any erosive disease of the skin; for example, lupus vulgaris is tuberculosis of the skin.

y Robert Mosley Yergason, American surgeon born in 1885, described this sign in 1931.

z Harry Finkelstein (1865–1939), surgeon, Hospital for Joint Diseases, New York.

aa The Greek word meros means thigh and algia means painful.