15 The Retina: Vascular Diseases II

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

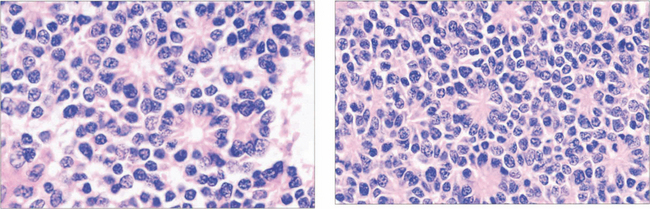

Fig. 15.2 (Top) These retinal trypsin digest preparations show early capillary damage and microaneurysms. (Top left) There are small areas of capillary loss, many of the capillaries are acellular, and small microaneurysms can be seen along dilated and more hypercellular capillaries. (Top right) More marked capillary dropout and well formed microaneurysms. (Bottom) An Indian ink injected preparation showing capillary nonperfusion, capillary loops and microaneurysms.

Top figures reproduced with permission from The Retinal Circulation, edited by Wise, Dollery and Hawkin, Harper & Row, 1971.

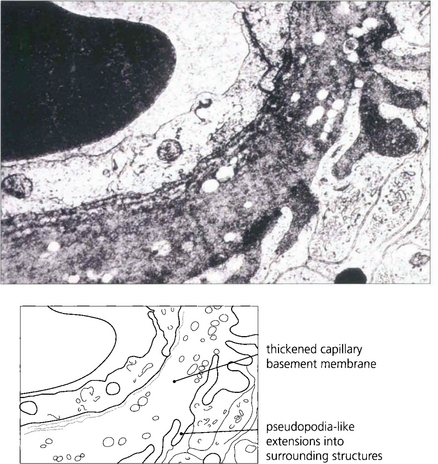

Fig. 15.3 An electron micrograph showing capillary basement membrane thickening and pseudopodia-like extensions into surrounding structures.

Fig. 15.4 A trypsin digest preparation showing eosinophilic staining of degenerate capillary pericytes.

CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

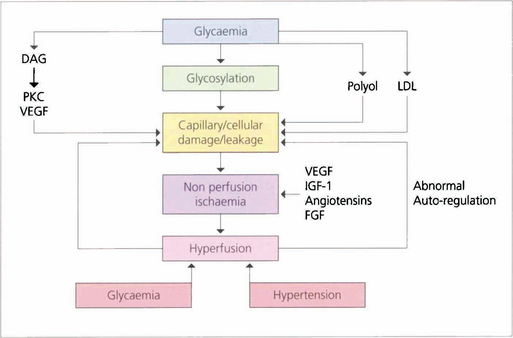

The initial clinical features of diabetic retinopathy are microaneurysms, small retinal haemorrhages and small areas of capillary closure (Table 15.1). Visual acuity is commonly normal at this stage, although subclinical changes in colour vision and contrast sensitivity might be found. This is followed by vascular leakage, hard exudate and cotton-wool spots. Retinopathy may progress to compromise vision in two ways: (1) maculopathy develops with oedema, lipid exudation or ischaemia, or (2) a proliferative retinopathy occurs, in which retinal hypoxia and neovascularization predominate and reduce vision by vitreous haemorrhage or traction retinal detachment. Not uncommonly, both mechanisms coexist in the same patient. Diabetic retinopathy is staged by its clinical features. Maculopathy is classified by extent as focal or diffuse, and by mechanism as exudative, ischaemic or mixed.

| Descriptive term | Features |

|---|---|

| No diabetic retinopathy (DR) | |

| Mild or moderate nonproliferative DR | Microaneurysms, retinal haemorrhages and exudate |

| Severe nonproliferative DR | Deep retinal haemorrhages in four quadrants, or venous beading or loops in two quadrants, or the presence of IRMAs |

| Proliferative DR without high-risk characteristics | New vessels on the disc smaller than one-third of a disc diameter without vitreous or preretinal haemorrhages or new vessel elsewhere only |

| Proliferative DR with high-risk characteristics | New vessels on the disc larger than one-third of a disc diameter or any new vessel with vitreous or preretinal haemorrhages |

| Advanced proliferative DR | Tractional retinal detachment, unresolved vitreous haemorrhage, rubeotic glaucoma |

NATURAL HISTORY

Risk factors for the progression of retinopathy are the duration of diabetes and the type (type I is worse than type II). Recent clinical trials have shown that meticulous long-term glycaemic and blood pressure control retards the onset and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Tightening poor glycaemic control may, however, initially markedly worsen retinopathy and cause neovascularization, possibly because initiating good control lowers retinal blood flow and exacerbates ischaemia. Careful monitoring of diabetic retinopathy when altering glycaemic control is therefore critical. Pregnancy, renal disease and cataract surgery may worsen the retinopathy whereas high myopia, optic atrophy, glaucoma, central retinal artery occlusion and carotid artery stenosis appear to protect, possibly by reducing retinal metabolic demand (Table 15.2). Diabetic retinopathy is not seen before puberty.

Table 15.2 Risk and protective factors for progression of retinopathy

| Risk factors | Protective factors |

|---|---|

| Duration of diabetes | High myopia |

| Poor long-term control | Optic atrophy |

| Tightening of poor control | Glaucoma |

| Hypertension | Carotid stenosis |

| Pregnancy | Retinal artery occlusion |

| Renal failure | |

| Hyperlipidaemia | |

| Puberty |

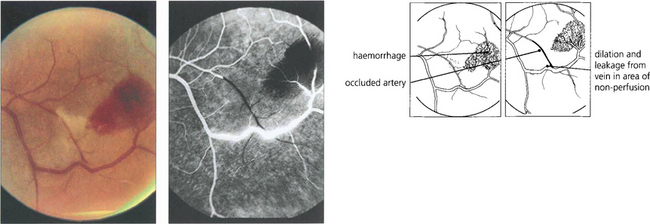

MILD AND MODERATE NONPROLIFERATIVE DIABETIC RETINOPATHY (NPDR)

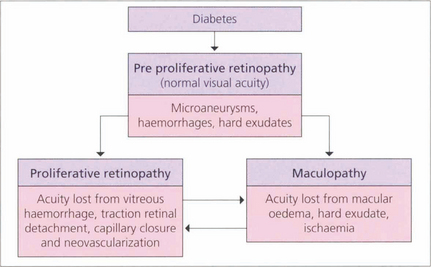

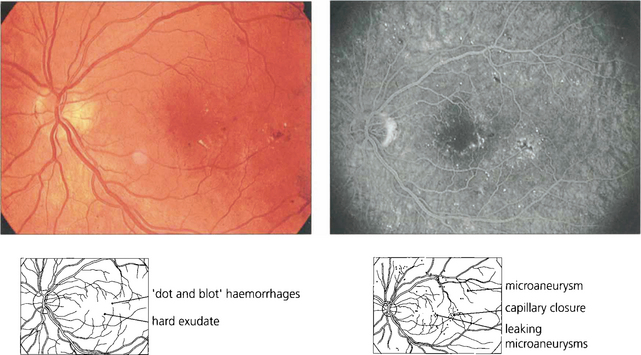

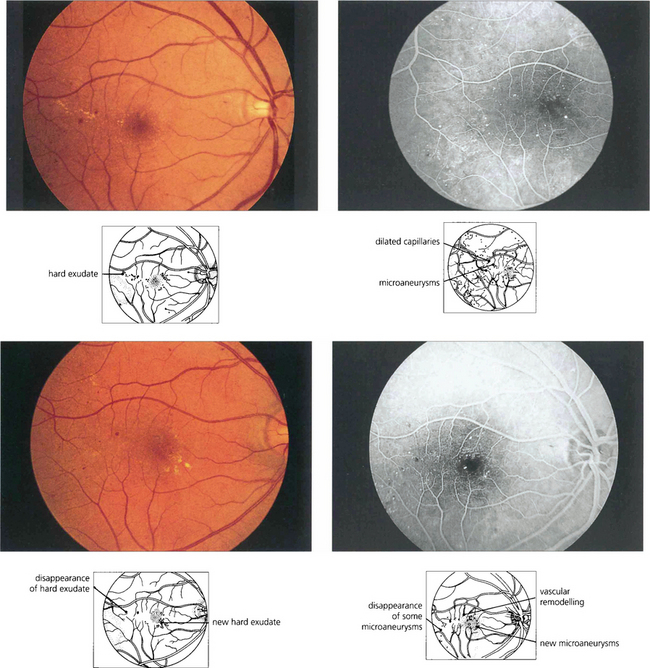

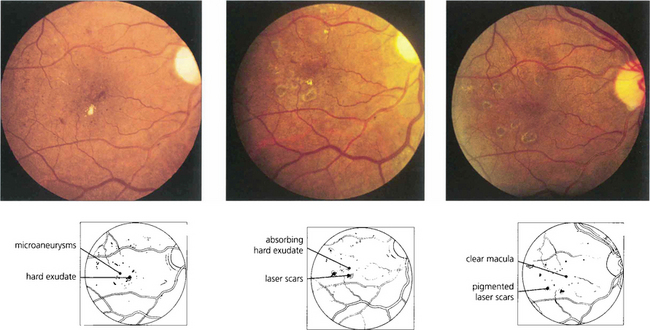

Fig. 15.6 This patient shows the typical changes of early retinopathy with scattered microaneurysms, blot haemorrhages and hard exudates and cotton-wool spots in the posterior pole. The macula and visual acuity are normal. The retinopathy can fluctuate, improving or deteriorating over a period of time. Fluorescein angiography demonstrates extensive microvascular changes throughout the posterior pole with scattered microaneurysms and minimal vascular leakage. Many more microaneurysms are visible that can be seen clinically. Although in some areas capillary patterns around the macula are irregular and show minor areas of capillary closure, they are, in the main, complete.

Fig. 15.7 With early retinopathy, the retina temporal to the macula is often susceptible to earlier and more pronounced changes; elsewhere in the posterior pole of this patient, retinopathy is comparatively sparse.

Fig. 15.9 Background retinopathy appearances can fluctuate and do not progress relentlessly. These photographs were taken 18 months apart. The later photograph (top right) shows that the exudates temporal to the macula have been absorbed spontaneously and new exudate has appeared inferior to the macula. Comparison of angiograms from the same patient shows there has been a considerable change in the pattern of the microaneurysms. New microaneurysms have formed and others, on the temporal side of the macula in particular, have disappeared over the same period of time.

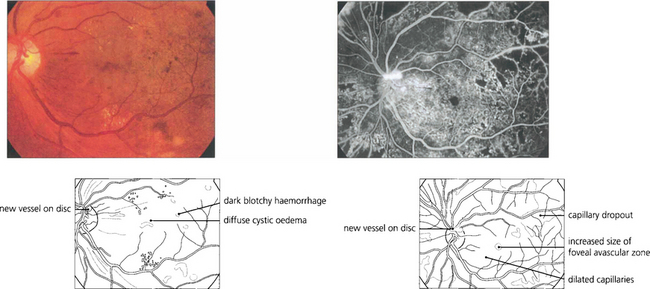

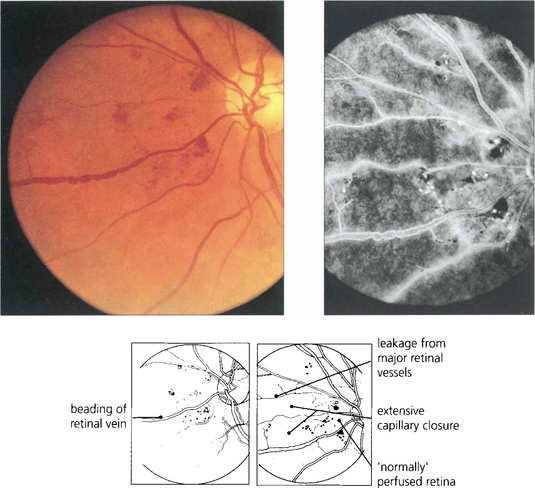

SEVERE NONPROLIFERATIVE DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

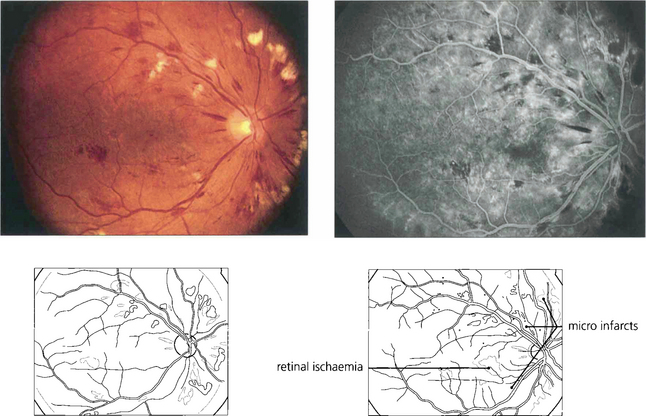

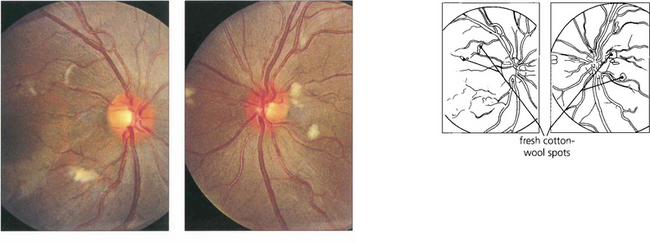

Fig. 15.10 Numerous cotton-wool spots, which persist for longer in diabetes (up to 3 months) than with other causes indicate marked retinal ischaemia, as confirmed on angiography.

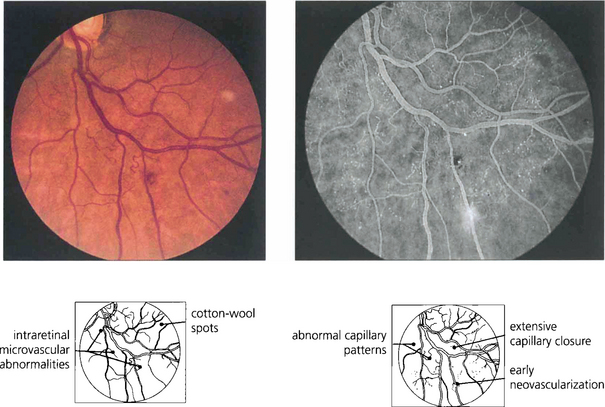

Fig. 15.11 Areas of intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMAs) with dilated tortuous veins along the inferior temporal arcade are seen in this patient. IRMAs represent intraretinal neovascularization and are found at the border of areas of nonperfusion. They are entirely intraretinal and do not leak fluorescein. As they are associated with nonperfusion it is not surprising that they are associated with an increased risk of PDR.

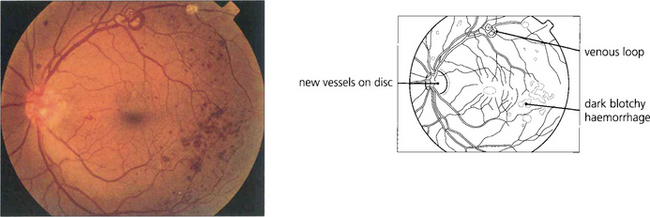

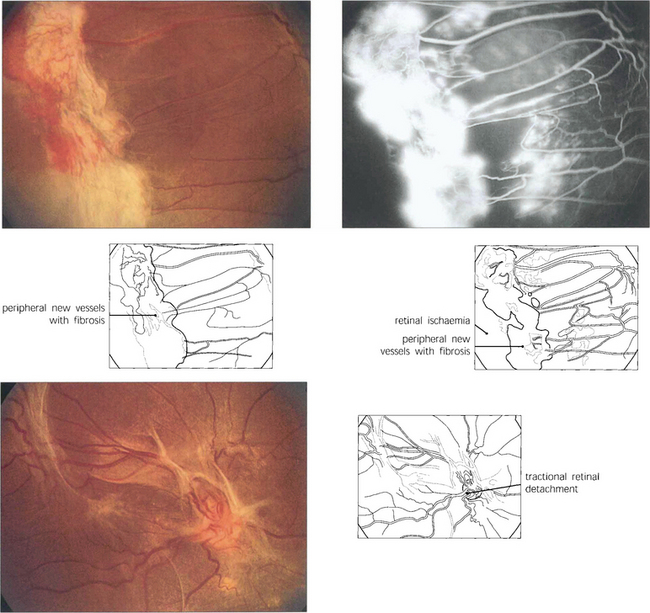

PROLIFERATIVE DIABETIC RETINOPATHY (PDR)

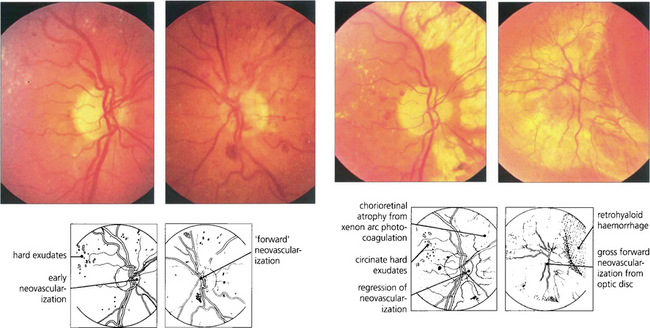

In common with neovascularization elsewhere in the eye these vessels have fenestrated endothelial cell junctions and tend to leak, while minor trauma and vitreous traction causes them to tear and bleed to cloud the ocular media. Subsequent formation of fibrous tissue produces traction bands between the retina and posterior vitreous face; these eventually contract and detach the retina (see Ch. 12).

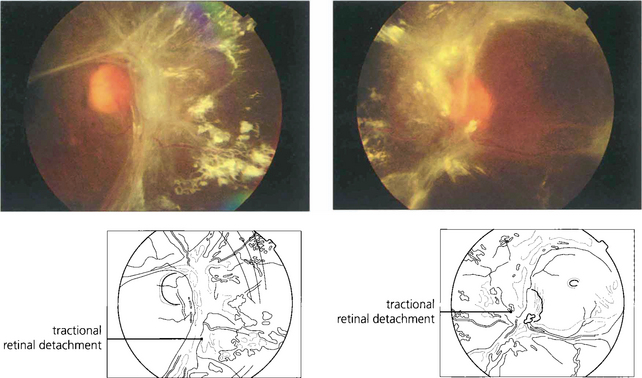

Clinically PDR is categorized by the location of neovascularization, either on the optic disc (NVD) or elsewhere (NVE), and by the presence of preretinal or vitreous haemorrhage and fibrosis with retinal traction. Advanced diabetic eye disease is characterized by vitreous haemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment (see Ch. 12).

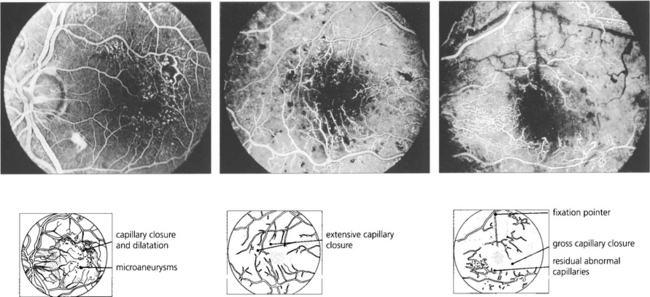

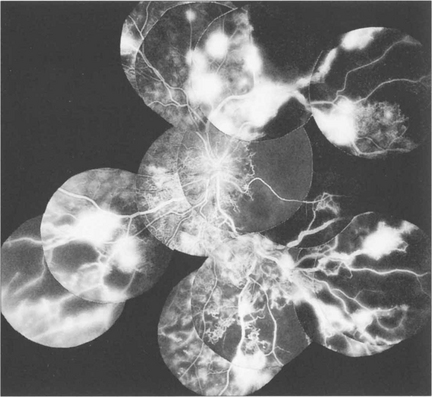

Fig. 15.16 This patient was a longstanding diabetic with renal failure and poor vision (CF) in each eye. A composite mount of the fluorescein angiogram of the right eye shows gross retinal capillary closure and demonstrates how neovascularization tends to arise on the retina at the border zone of the perfused and ischaemic areas. This eye later developed rubeotic glaucoma.

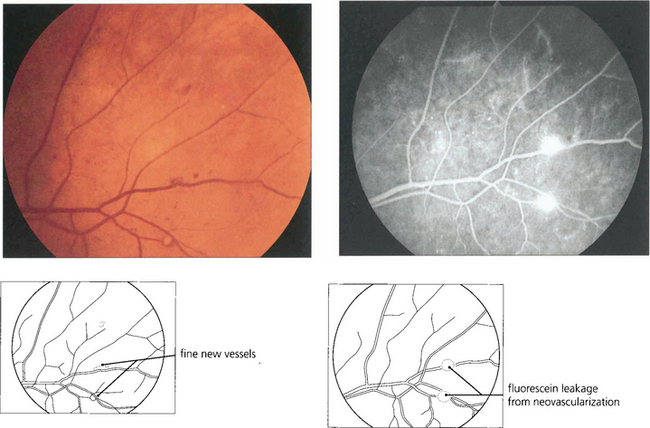

Fig. 15.17 Retinal neovascularization begins as fine thready vessels that are difficult to see, usually adjacent to a vein. Angiography shows them more clearly because of their leakage.

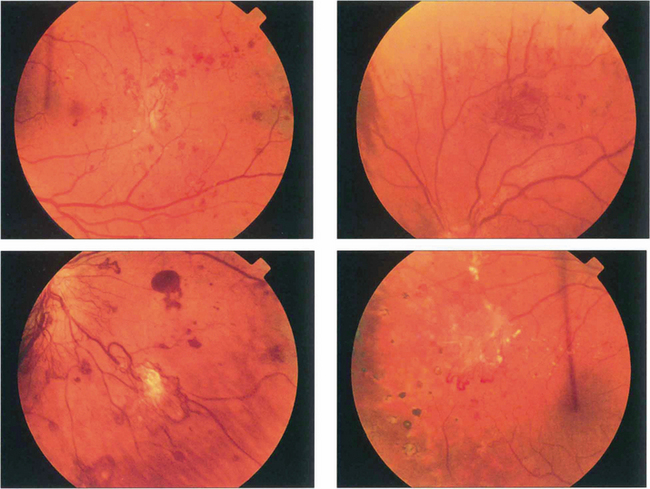

Fig. 15.18 More advanced changes are seen in these patients. Peripheral neovascular tissue is initially seen as a flat neovascular fan; in more marked cases there is accompanying fibrous and retinal traction.

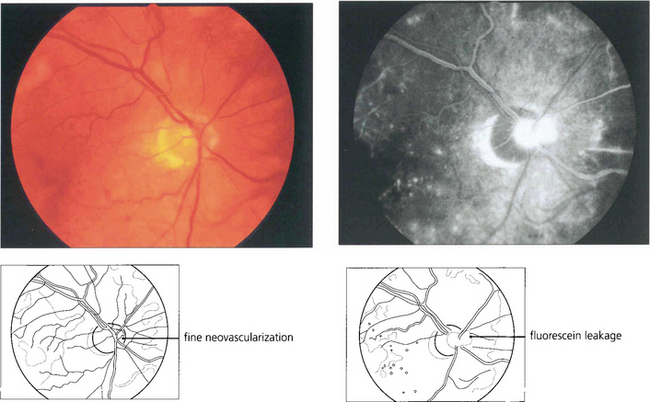

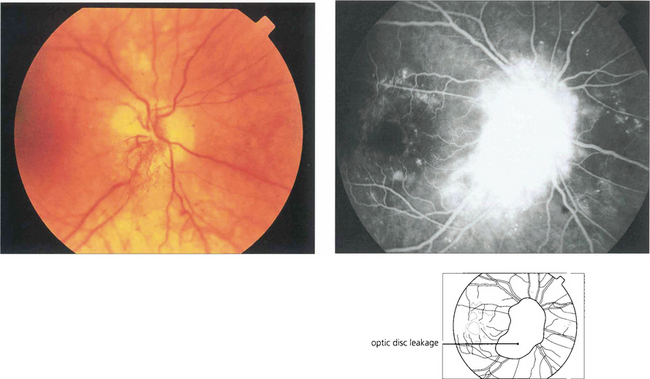

Fig. 15.19 Neovascularization on the optic disc carries a more serious visual prognosis than peripheral new vessel formation, and it is therefore essential to detect this early. In common with all neovascular tissue, neovascularization leaks intensely on angiography; this sign can, therefore, be very helpful in early diagnosis.

Fig. 15.20 Neovascularization starts as fine, flat, thready vessels on the disc that do not have a normal anatomical distribution. With time it increases in extent and severity and with collapse of the vitreous gel is pulled forwards on the posterior hyaloid face.

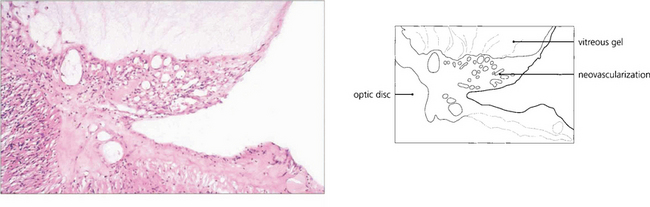

Fig. 15.21 This optic disc shows a prominent neovascular fan which has been pulled forwards by the detached vitreous gel; the vessels can be seen multiplying on the retrohyaloid face. Movements of the gel with ocular movement will put traction on these delicate vessels producing haemorrhage.

Fig. 15.22 Histological examination shows vascularized fibroglial tissue extending from the disc and adherent to the vitreous; note that the neovascularization does not invade the gel.

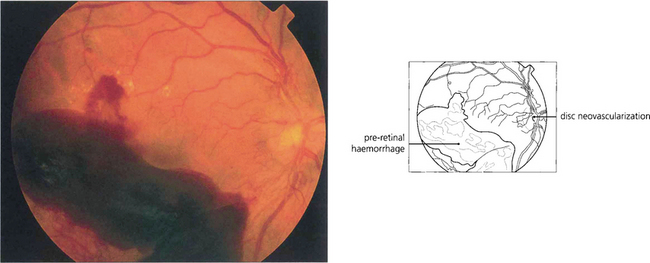

Fig. 15.23 Preretinal and vitreous haemorrhages are a serious complication of neovascularization both on the optic disc and in the peripheral retina.

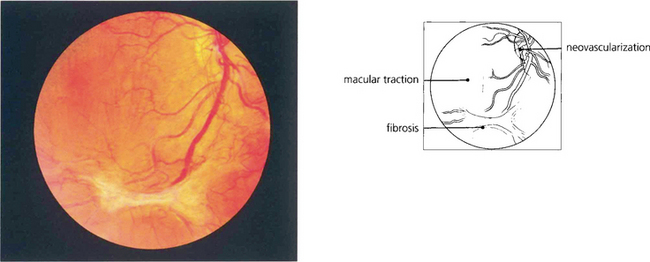

Fig. 15.24 This patient has marked neovascularization on the optic disc and along the inferior temporal arcade. Vitreoretinal adhesions along the temporal vascular arcades are very common in diabetes. Here localized fibrotic changes have produced traction on the retina and distortion of the macula. If untreated the natural history would be of further fibrotic tissue formation and traction, progressing to localized or general traction detachment of the retina.

Fig. 15.25 In advanced cases vision is lost as a result of a combination of vitreous haemorrhage and traction detachment. In a few patients, the retinopathy ‘burns out’ before this final stage and leaves inactive fibrotic tissue with varying distortion of the retinal architecture. This patient, who never had photocoagulation, was left with visual acuities of hand movements and 20/60.

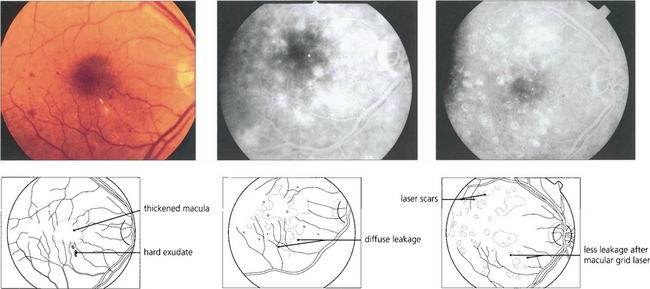

DIABETIC MACULOPATHY

Diabetic maculopathy is the leading cause of blindness in diabetic patients, especially noninsulin-dependent (type II) diabetics. It results from lipid exudation, oedema and ischaemia, frequently in combination. The ETDRS used the term ‘clinically significant macular oedema’ (CSMO) for the following signs: retinal thickening (i.e. oedema) at or within 500μm of the foveal centre, hard exudates at or within 500μm of the foveal centre if associated with thickened adjacent retina or a zone of retinal thickening covering at least one disc diameter (1500μm) within one disc diameter of the foveal centre. Retinal thickening can be satisfactorily assessed only by stereo-biomicroscopy; optical coherence tomography (OCT) (see Chs 1 and 12) has an increasing role in objectively assessing retinal thickness and the response to treatment.

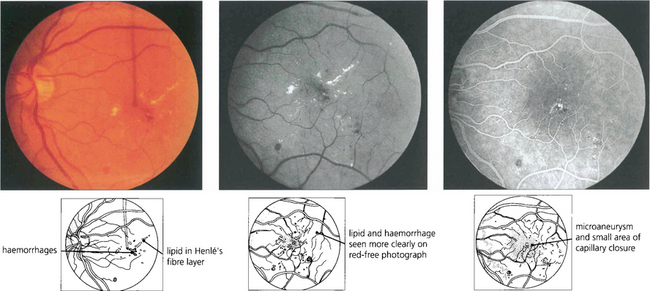

Fig. 15.26 Lipid exudation into the macula originates from a leaking vascular anomaly, usually a microaneurysm or area of capillary closure, and spreads linearly in Henlé’s fibre layer. It is accompanied by oedema and thickening of the macula. Red-free photography shows lipid and vessels more clearly and the angiogram shows that the leak originates from a microaneurysm surrounded by a small area of capillary closure.

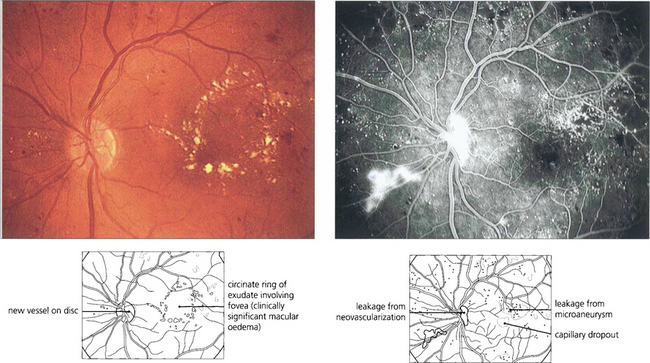

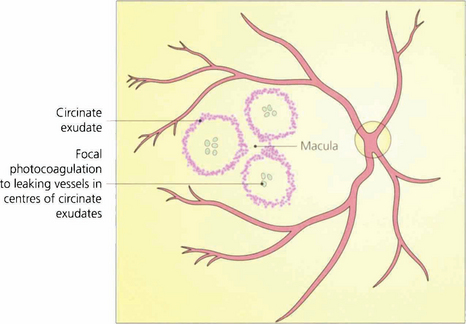

Fig. 15.27 Circinate patterns of exudate form around leaking foci in more established cases. The angiogram shows the vascular abnormalities in the centre of these lesions.

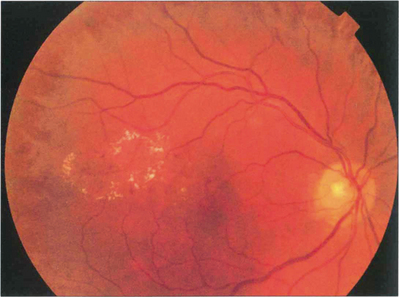

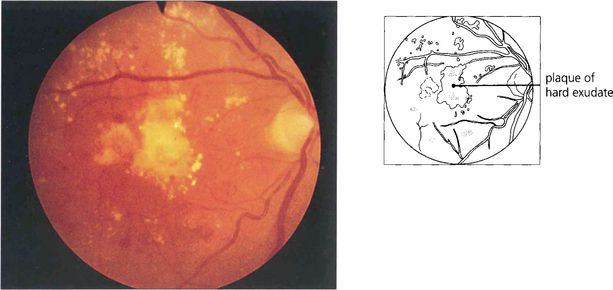

Fig. 15.28 Advanced exudative maculopathy results from prolonged and untreated deposition of lipid within the macula. Circinate exudates coalesce to produce massive plaques and although these will absorb if the sources of vascular leakage are destroyed by photocoagulation neuronal destruction has occurred to such an extent that vision rarely improves.

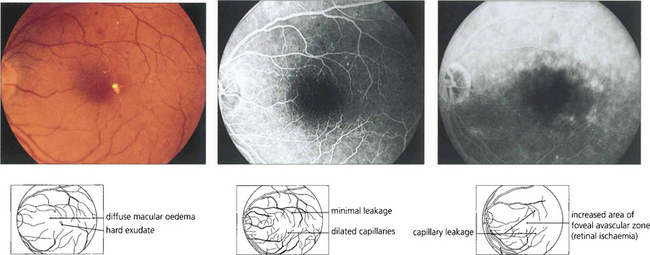

Fig. 15.29 Purely oedematous types of maculopathy are less common. Vascular changes produce macular oedema with relatively little haemorrhage or exudation. These maculas have a thickened, rather amorphous, appearance and cystoid spaces are sometimes visible. These changes are best appreciated by stereoscopic examination. Visual impairment is usually severe. Characteristically on angiography these individuals show diffuse capillary dilatation over the whole posterior pole with relatively few focal changes. Later phases show massive vascular leakage.

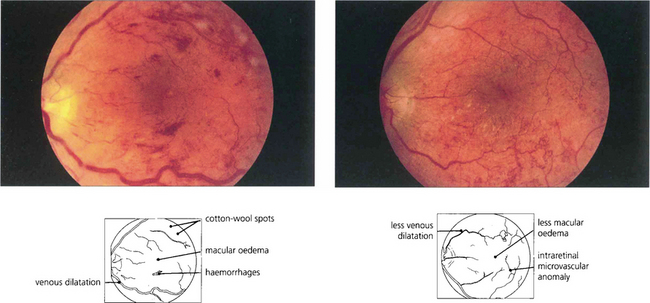

Fig. 15.30 Diabetic retinopathy can progress dramatically during pregnancy to maculopathy or proliferative disease. This patient had a background retinopathy before her pregnancy but developed marked macular oedema so that acuity had fallen to 20/80 by 36 weeks when labour was induced. At 3 weeks postdelivery (right) the oedema had resolved spontaneously and acuity improved to 20/30.

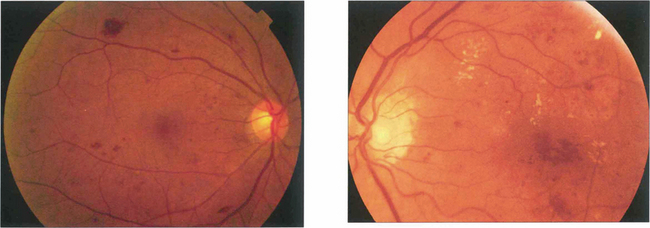

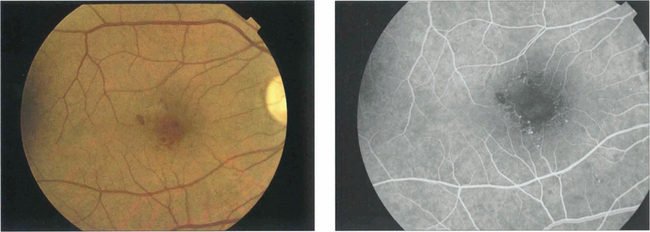

Fig. 15.31 With ischaemic maculopathy capillary closure produces deep intraretinal haemorrhage, oedema and ischaemia. Exudates are comparatively sparse but may surround the central disturbance. The angiogram shows loss of the macular capillary circulation but the patient still maintained an acuity of 20/80.

DIABETIC PAPILLOPATHY

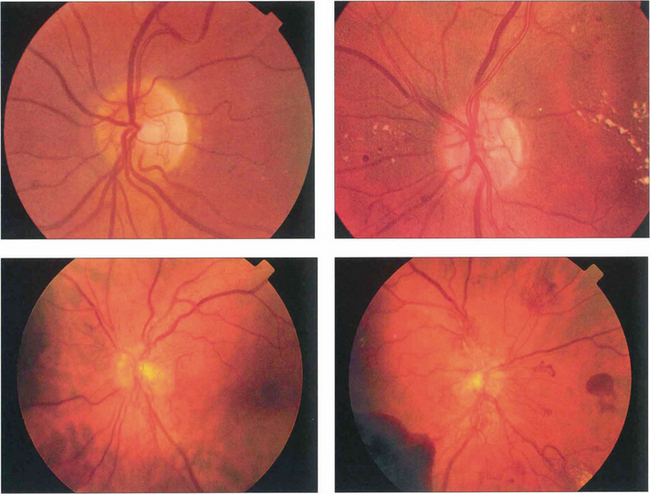

Fig. 15.33 This is an uncommon condition usually presenting with unilateral or bilateral optic disc swelling in a young adult diabetic. It is often associated with signs of a mild optic neuropathy and only mild or moderate retinopathy. The aetiology is thought to be ischaemic small vessel disease. The visual prognosis is generally good, with resolution without treatment.

MANAGEMENT OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

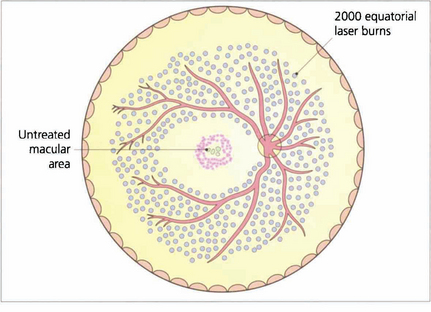

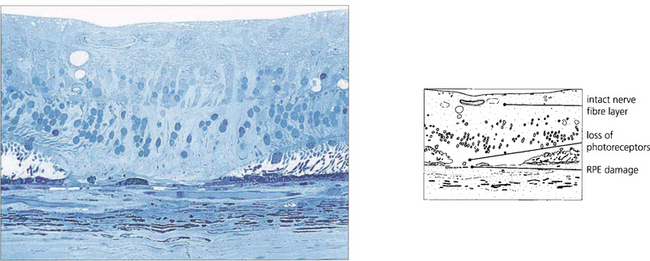

Fig. 15.34 Proliferative retinopathy requires treatment by panretinal photocoagulation. By sparing the macular area panretinal photocoagulation does not affect visual acuity. Some 2000 burns are usually given to the equatorial retina, normally in one or two treatments, to produce regression of optic disc neovascularization within a few weeks. A few patients require much more treatment and all patients need to be followed up carefully with further treatment if neovascularization reappears. After panretinal photocoagulation visual disability is surprisingly slight. Preservation of the inner nerve fibre layer avoids the production of arcuate field loss and patients normally notice only marginal constriction of their visual field and sometimes a reduction in their visual performance in the dark. It is essential that patients are counselled about the effect of panretinal photocoagulation on their ability to drive especially on the right.

Fig. 15.35 The histology of a laser burn shows that there is atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptors in the area of the burn. The energy is taken up in the RPE and, provided the amount of energy is restricted, the thermal injury is localized and the inner nerve fibre layer spared. Damage to this layer would result in nerve fibre damage and visual field defects.

By courtesy of Professor J Marshall.

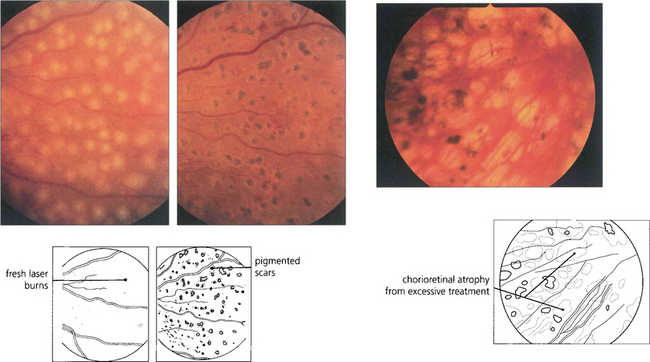

Fig. 15.36 In practice, the burns must be of sufficient intensity to produce a soft white reaction in the retinal pigment epithelium; a dense white reaction indicates damage to the inner retina. Within a few days the burns become pigmented atrophic scars (middle). Photocoagulation that is excessive leads to damage of the RPE and subsequent atrophy (right), causing peripheral field constriction and night blindness.

Fig. 15.37 The efficiency of panretinal photocoagulation is demonstrated by this patient who participated with informed consent in a controlled trial of panretinal photocoagulation in the early 1970 s. (Left pair) Early neovascularization is seen on each optic disc, confirmed by the presence of leakage on the fluorescein angiogram. The right eye was treated with xenon arc photocoagulation and the left remained untreated as a control eye. (Right pair) Fifteen months after panretinal photocoagulation to the right eye, the new vessels on the optic disc have regressed and marked chorioretinal scars can be seen from the photocoagulation (excessive treatment by present standards). Visual acuity remained normal in this eye, with loss of peripheral visual field and night blindness. In contrast the left deteriorated to perception of light with a marked neovascular membrane arising from the optic disc with total traction retinal detachment. This eye now has a substantial risk of developing rubeotic glaucoma.

Fig. 15.38 Exudative maculopathy is treated by obliterating the leaking microvascular abnormalities that produce the hard exudate. These can often be identified clinically without the need for routine fluorescein angiography. Absorption of hard exudates takes several weeks, depending on their extent.

Fig. 15.39 Fundus appearance (left) before and (middle) after laser photocoagulation. Before treatment, early deposition of hard exudate can be seen in the macular area. Eight weeks after treatment the exudate is in the process of being absorbed; 1 month later it has disappeared and the scars in the retinal pigment epithelium from the photocoagulation can be seen. Such treatment does not produce any visual impairment as long as the burns are outside the foveal avascular zone and of sufficiently low intensity to protect the overlying retinal nerve fibres.

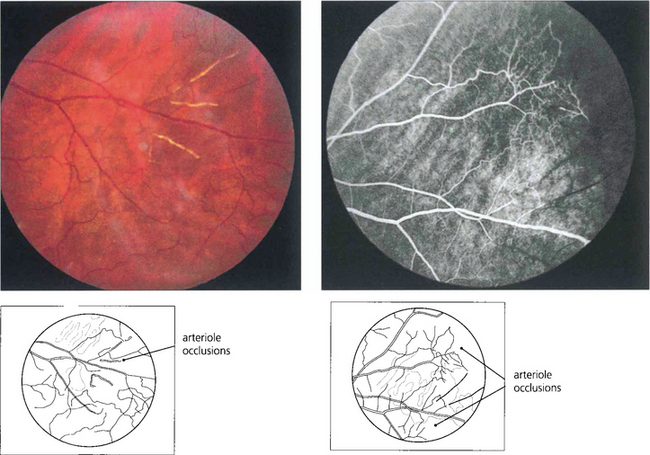

SICKLE CELL RETINOPATHY

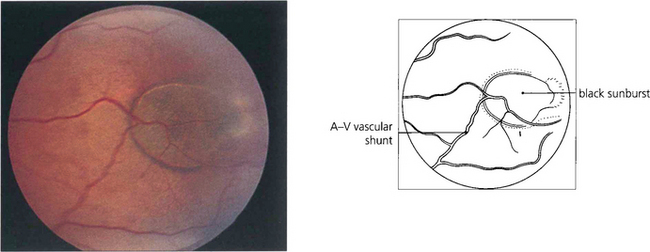

Fig. 15.42 Acute arteriolar vascular occlusions can produce intraretinal or subretinal haemorrhage (salmon patches), which are red or yellowish and about one disc in diameter. They are seen in the equatorial retina adjacent to the occluded arteriole and are a sign of recent infarction causing necrosis of the vascular wall and haemorrhage. If the RPE is damaged they resolve to leave a pigmented scar (black sunburst).

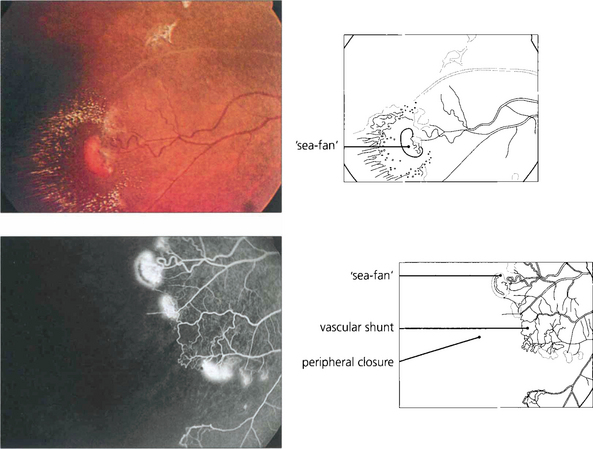

Fig. 15.43 Neovascularization occurs in the peripheral retina along the demarcation between perfused and nonperfused retina. Early changes are seen in this patient. Abnormal vascular shunts in the peripheral retina are common. Sickle cell retinopathy is common in the West Indies; these neovascular fans are known as ‘sea-fans’, reminiscent of the local coral formations.

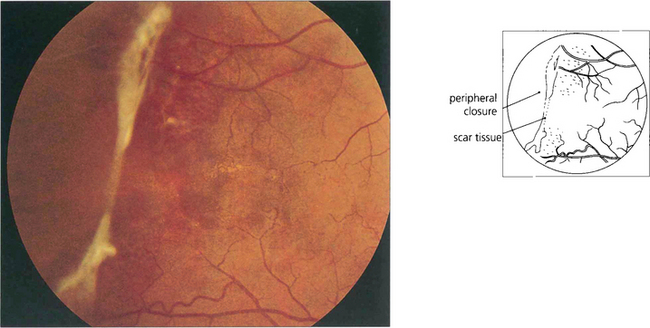

Fig. 15.44 This patient shows inactive fibrotic changes in the peripheral retina. Vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment are uncommon in sickle cell retinopathy probably because the lesions tend to infarct spontaneously. Most patients can be watched without treatment. Photocoagulation of fronds does not appear to improve the natural history of the disease and may make the disease move more centrally.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (SLE)

Retinopathy from SLE occurs as a combination of microvascular ischaemia from vasculitis and changes from secondary systemic hypertension, anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Choroidal infarcts can be seen and occasionally acutely ill patients present with bullous subretinal fluid from choroidal involvement due to acute systemic hypertension or vasculitis. Scleritis is common (see Ch. 5) but uveitis does not occur. The predominant features of SLE retinopathy are cotton-wool spots in the absence of hypertension and retinal haemorrhages and Roth’s spots, especially in patients with haematological changes. Antiphospholipid antibodies are found in many patients with SLE; these are associated with systemic venous thrombotic episodes and may also contribute to the retinopathy in some patients.

Fig. 15.46 Skin lesions are common with SLE. A vasculitic facial rash in a ‘butterfly’ distribution is the most common manifestation.

By courtesy of Dr G R V Hughes.

Fig. 15.47 This 14-year-old boy presented with acute lupus, renal failure and dementia from cerebral involvement and died from renal failure. Both fundi show numerous cotton-wool spots.

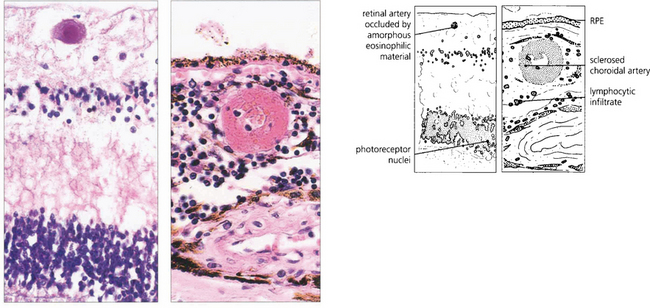

Fig. 15.49 Histological examination from a patient with similar retinal signs to those seen in Fig. 15.45 shows an occluded retinal arteriole, with no evidence of vasculitis, and sclerosed choroidal vessels as a consequence of systemic hypertension. In the choroid there is a marked lymphocytic infiltrate.

RETINAL VASCULAR ANOMALIES

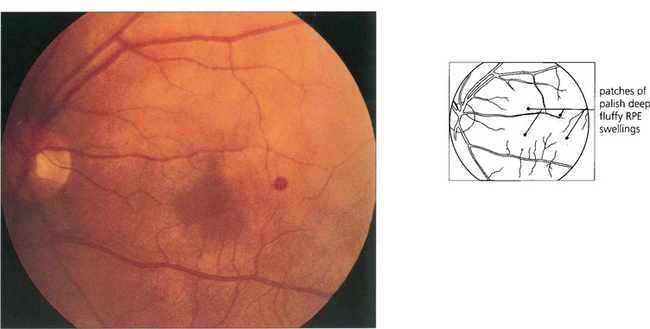

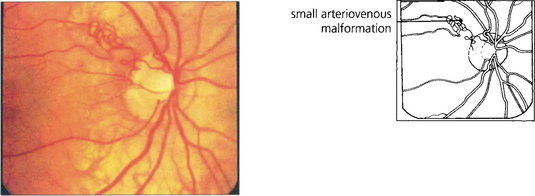

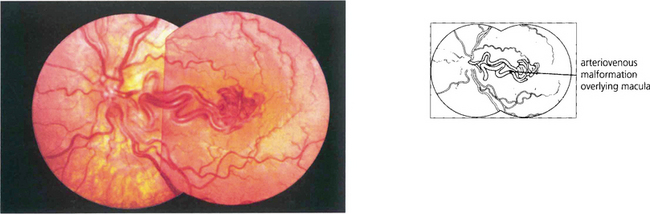

RACEMOSE MALFORMATIONS

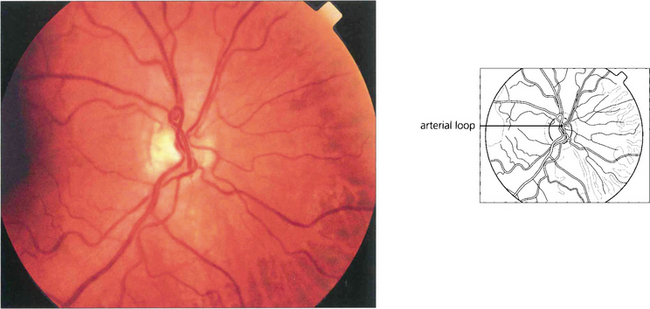

These are thought to be developmental rather than genetic in origin. Rarely, retinal arteriovenous malformations or anastomoses can be associated with intracranial vascular abnormalities (Wyburn–Mason syndrome). Sturge–Weber syndrome affects the choroidal vessels rather than the retinal circulation (see Ch. 9). Visual loss from vascular leakage, accumulation of hard exudates or haemorrhage is rare.

Fig. 15.51 Arterial loops can be seen projecting forwards from the disc. They occasionally undergo torsion, causing retinal infarction.

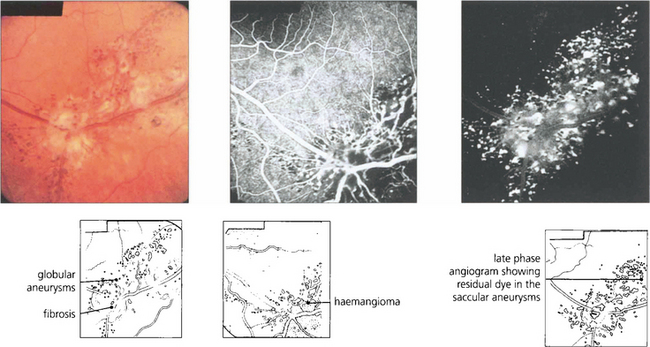

CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA

Fig. 15.54 Cavernous haemangioma of the retina is a rare benign lesion. It consists of isolated clusters of dilated blood vessels within a fibrous matrix. The lesions do not progress or generally cause symptoms and are not associated with any systemic vascular disease. Well documented cases have been shown to remain unchanged over many years. The fluorescein angiogram shows that the dilatations fill with dye in the late venous phase, often with a fluid level from the stagnant circulation (fluorescein on top of the stagnant red blood cells), but with no vascular leakage.

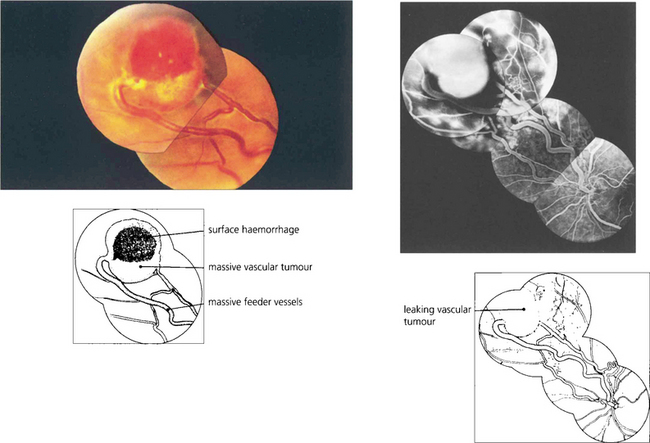

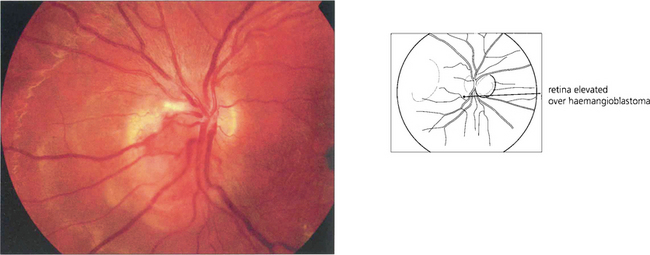

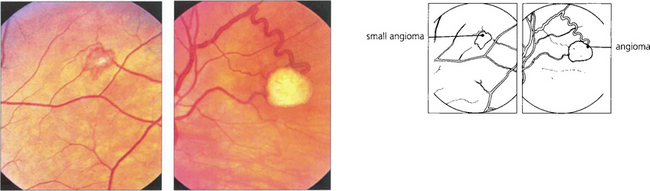

VON HIPPEL–LINDAU DISEASE

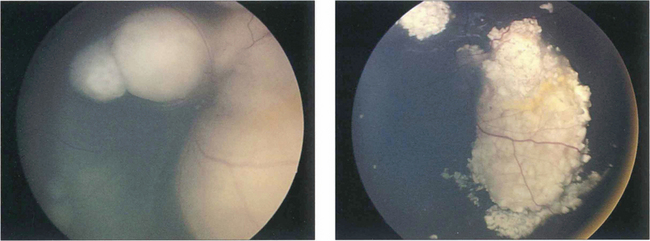

Fig. 15.55 Early tumours are seen in the peripheral retina as red or yellowish bulbous vascular lesions with enlarged feeder vessels. Fluorescein angiography can be very helpful in detecting early lesions which are easily obliterated by photocoagulation.

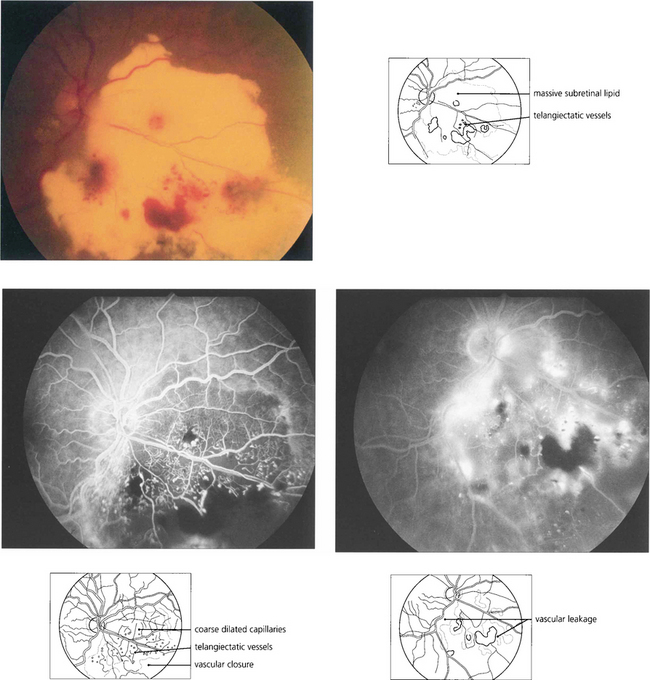

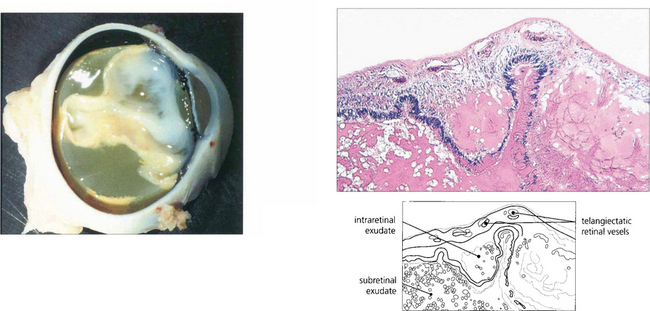

COATS’ DISEASE, LEBER’S MILIARY ANEURYSMS AND PARAFOVEAL TELANGIECTASIA

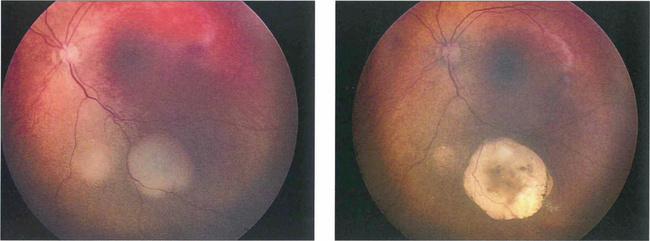

Fig. 15.58 This boy has massive subretinal exudates associated with a localized area of vascular malformation, which leaks in the later phase of the angiogram.

Fig. 15.59 Massive subretinal lipid exudate and serous retinal detachment in a young boy with Coats’ disease can simulate a retinoblastoma. Apart from the difference in age of presentation, the differential diagnosis is aided by demonstrating the vascular anomalies and the yellowish-green lipid exudate, in contrast to the white or pink fleshy appearance of retinoblastoma.

Fig. 15.60 Lipid-containing exudate fills the subretinal space and the retina is totally detached. Histological examination shows telangiectatic vessels in the retina and proteinaceous and lipid-containing exudate in the retina and subretinal space.

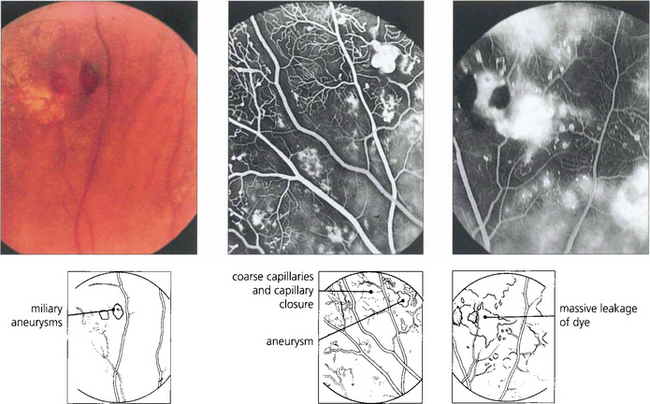

Fig. 15.61 Peripheral miliary aneurysms in another patient. Fluorescein angiography demonstrates the saccular vascular dilatation accompanied by coarseness and closure of the capillary bed. Massive leakage of dye occurs in the late phases, although some degree of capillary closure occurs retinal neovascularization is not seen.

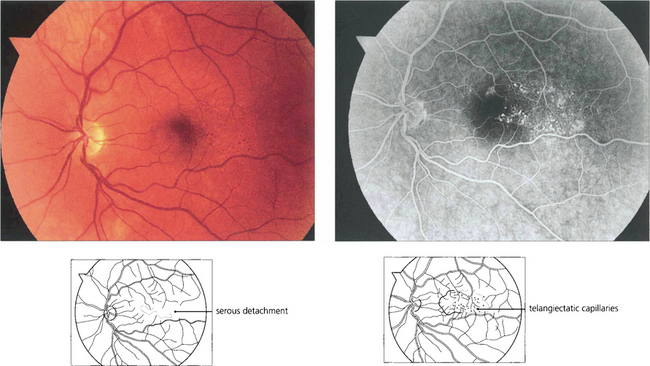

Fig. 15.62 Parafoveal telangiectasia presents with distortion, macular oedema and serous retinal detachment in this middle-aged man, who presented with visual blurring in the right eye. Fluorescein angiography in the early phases demonstrates dilated telangiectatic capillaries adjacent to the macula; these leak slowly as the angiogram progresses. Such patients require a careful examination of the peripheral retina for occult vascular abnormalities. Patients can be helped by photocoagulation to the abnormal vascular tissue.

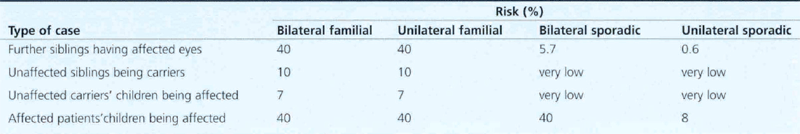

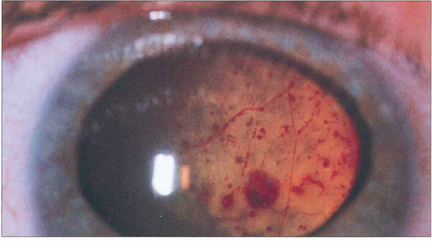

RETINOBLASTOMA

Genetic counselling is mandatory and requires a thorough examination of both parents and all siblings (Table 15.3). The variable penetrance of dominantly inherited disease means that without genetic analysis, a definite answer cannot be given as to whether an isolated unilateral case is sporadic or familial. The parents can be given the statistical risk of further siblings being affected, an affected child transmitting the gene to the next generation, or the chances of an unaffected sibling being an asymptomatic carrier.

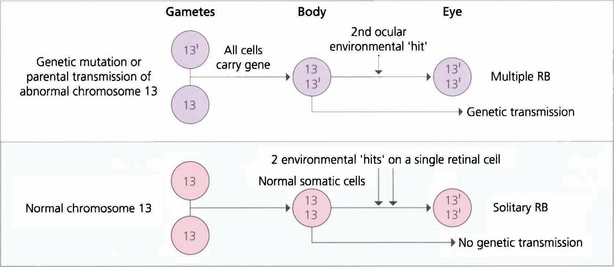

Fig. 15.63 Retinoblastoma is linked to deletion of a tumour suppressor gene known as RB1 on the long arm of chromosome 13. Only one normal copy of the gene is required to suppress retinoblastoma. In familial cases, one allele of the tumour suppressor gene is already inactivated in the germline so that all cells in the body are affected but the other copy remains active to continue production of tumour suppressor protein (heterozygote). Loss of the second allele, however, abolishes this production and leads to unregulated growth; this is considered the second hit of the ‘two-hit hypothesis’. Thus, paradoxically, although retinoblastoma is dominantly inherited, the way in which a cell develops malignancy is ‘recessive’ as both copies of the gene need to be inactivated. Sporadic cases of retinoblastoma develop when both alleles are inactivated, either by new genetic (i.e. not inherited in the germline but inheritable to new generations) or somatic (nonheritable) mutation. About 30 per cent of all sporadic disease is thought to be due to new genetic mutations. Environmental factors such as viral infections are believed to be responsible for somatic mutations.

Fig. 15.64 Bilateral leucocoria is seen in a 1-year-old child with gross bilateral ocular involvement. A convergent squint is present. Other common causes of leucocoria in childhood are retinopathy of prematurity (see Ch. 14), persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (see Ch. 8), toxocariasis (see Ch. 10), coloboma (see Ch. 17) and Coats’ disease (see Fig. 15.56).

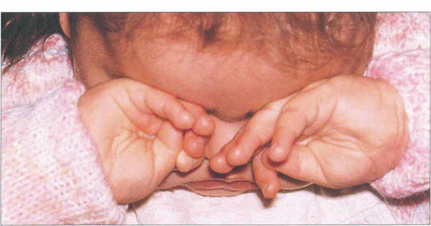

Fig. 15.65 In common with any other bilaterally blinding diseases of childhood, affected children poke and rub their eyes, probably to obtain some visual sensation by the production of phosphenes from manual stimulation.

Fig. 15.66 This child has a buphthalmic left eye with a white pupil.

By courtesy of Mr J Hungerford.

Fig. 15.67 Following chemotherapy and laser thermotherapy this tumour has become flatter, whiter and more circumscribed indicating regression of the tumour.

By courtesy of Mr J Hungerford.

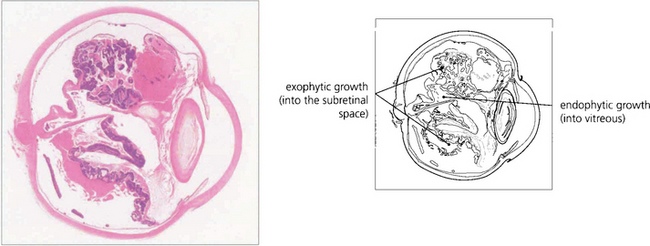

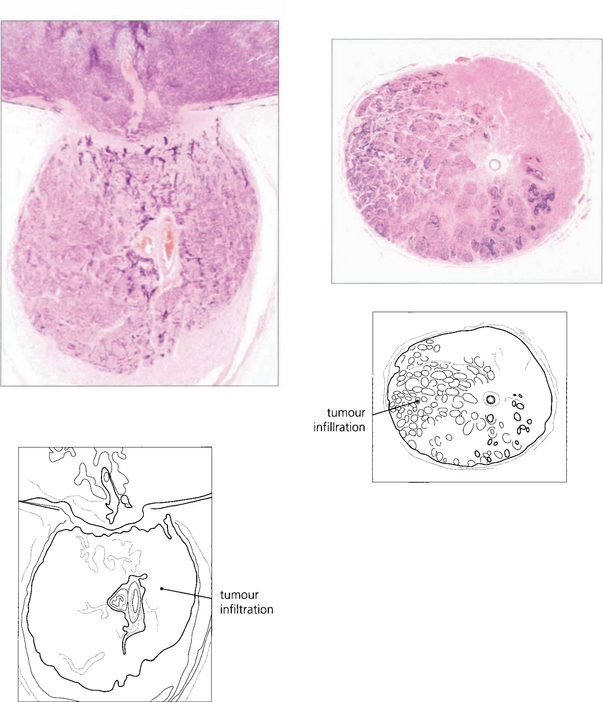

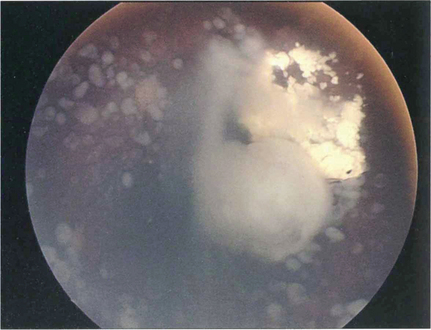

Fig. 15.68 This child has massive subretinal tumour. Growth into the gel is known as an endophytic tumour whereas subretinal spread is known as an exophytic tumour. Most tumours show both components. Rarely, tumours may spread diffusely in the retina. Calcification is common, occurring in areas of necrosis within the tumour and this is a helpful diagnostic sign which can be recognized ophthalmoscopically as chalky white areas and confirmed by ultrasonography or CT scanning. Following chemotherapy this tumour has become white, calcific and well circumscribed indicating a good response to the treatment

By courtesy of Mr J Hungerford.

Fig. 15.69 This child shows vitreous seeding following a relapse after chemotherapy

By courtesy of Mr J Hungerford.