14 The Retina: Vascular Diseases I

RETINAL VASCULAR OCCLUSIONS

The posterior ciliary circulation supplies the optic disc and choroid through the short posterior ciliary arteries and the circle of Zinn (see Ch. 17); the central retinal artery leaves the ophthalmic artery in the orbit and only supplies the capillaries on the surface of the optic disc and the retina (see Ch. 20). Retinal vascular occlusions are a common cause of visual loss especially in elderly, hypertensive, diabetic or arteriosclerotic patients. Patients usually present with sudden unilateral visual loss although this might be noticed only coincidentally some time after the initial event particularly in elderly people. All patients need a careful assessment for associated underlying systemic hypertension, diabetes or other atherogenic diseases. Subclinical cardiac and cerebrovascular disease is frequently present and patients should be investigated with these in mind as prophylactic medical or surgical treatment might be indicated to limit or prevent further systemic vascular damage.

ARTERIAL OCCLUSIONS

CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

This is usually a disease of the elderly and is most commonly caused either by thrombosis in the retrobulbar portion of the central retinal artery or blockage of the artery by an embolus which usually originates in the heart or carotid artery. Complete occlusion may be preceded by attacks of amaurosis fugax. All patients should be screened for hypertension, diabetes, cardiac valvular and coronary artery disease and carotid atheromatous disease. Temporal arteritis usually presents as an anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy but occasionally causes a central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and needs to be excluded (see Ch. 17). In younger patients, the underlying aetiology is occasionally found to be an inflammatory arteritis of which polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus and syphilis are perhaps the commonest causes. Spasm of the central retinal artery is an ill-defined and controversial phenomenon that occurs only in exceptional circumstances such as drug toxicity with ergot overdosage or pre-eclamptic toxaemia of pregnancy. CRAO is a rare feature of migraine.

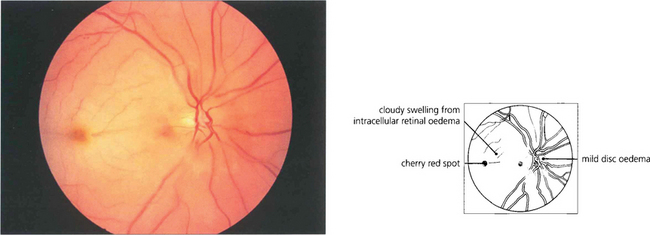

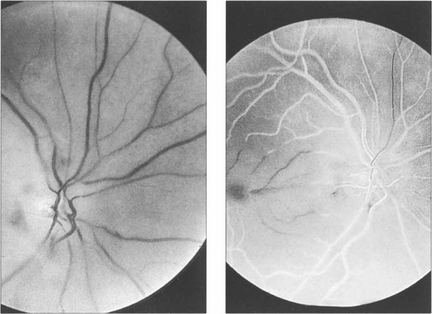

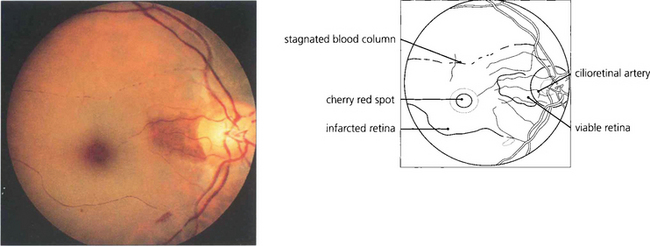

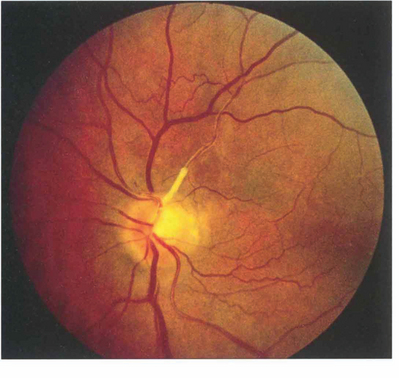

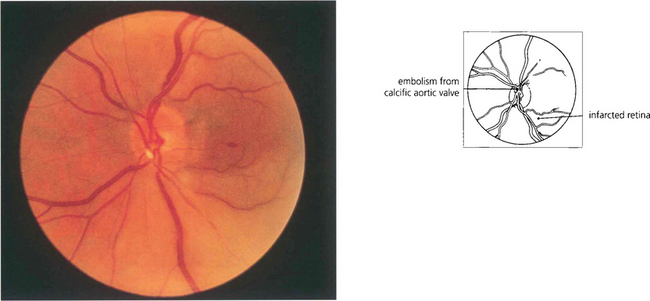

Fig. 14.1 The fundus of a recent CRAO shows a cloudy, opaque and swollen infarcted retina particularly noticeable in the posterior pole where the retina is thickest. The fovea is the thinnest area of the posterior retina and there is little tissue here to infarct so that the underlying redness of the choroid is seen contrasting with the whiteness of the surrounding infarcted retina to give the classical ‘cherry red spot’ appearance. Within a few hours mild swelling of the optic disc often appears due to products of retrograde axoplasmic transport accumulating in the optic nerve head. In the acute stage blood in the retinal arteries is dark from stagnation and the arteries themselves are often attenuated. These acute appearances subside over a period of 2–4 weeks, usually leaving the eye with perception of light. Complete blindness should suggest more extensive vascular occlusion involving the choroidal or optic disc circulation or ophthalmic artery.

Fig. 14.2 Fluorescein angiography is not usually performed but if it is done in the acute stages there is a considerable delay in filling of the central retinal artery circulation following injection of dye; this is seen as black retinal arteries against the normal background choroidal fluorescence which, of course, is unaffected by the occlusion. The artery fills eventually either directly or by retrograde flow from the venous circulation. The central vessels in the posterior pole fill poorly, possibly due to the retinal oedema increasing external tissue pressure.

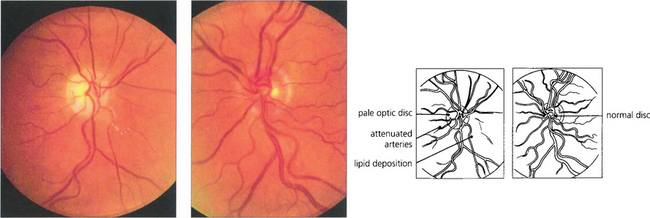

Fig. 14.3 Late changes following CRAO in the right eye. The optic disc is pale and the branches of the central retinal artery are attenuated in contrast to those of the normal left eye. Note the irregular whitish-yellowish deposition in the arterial walls which is probably a mixture of gliosis and lipid deposition from vascular endothelial damage.

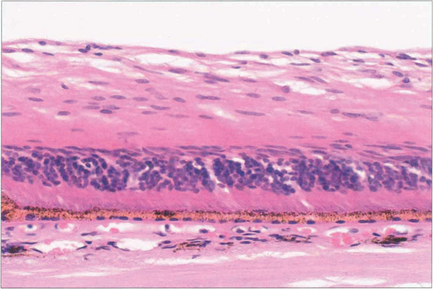

Fig. 14.4 Histology shows atrophy of the inner two-thirds of the retina, (supplied by the retinal circulation), following CRAO. The outer retina is maintained by the choroid (see Ch. 13).

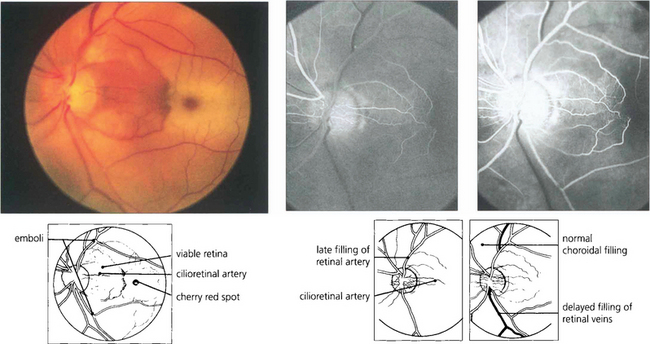

Fig. 14.5 Cilioretinal arteries of varying size are found in about 20 per cent of eyes. These are part of the posterior ciliary circulation and are therefore spared in a CRAO. The patch of retina supplied by the artery is left viable; if the patient is fortunate this will include the macula. A small cilioretinal vessel is seen clearly in this patient supplying an area of retina temporal to the optic disc. Minute cholesterol emboli can be seen in the inferior and superior temporal arteries and also in a small branch artery adjacent to the macula, indicating the aetiology of the occlusion. Fluorescein angiography demonstrates the slow rate of filling of the retinal circulation and the normal filling of the cilioretinal artery and choroid.

Fig. 14.6 This example of cilioretinal artery sparing in the presence of a CRAO in a pigmented eye demonstrates clumping of the blood column in the inferior temporal branch artery. This characteristic sign of a stagnant retinal circulation is known as ‘cattle trucking’.

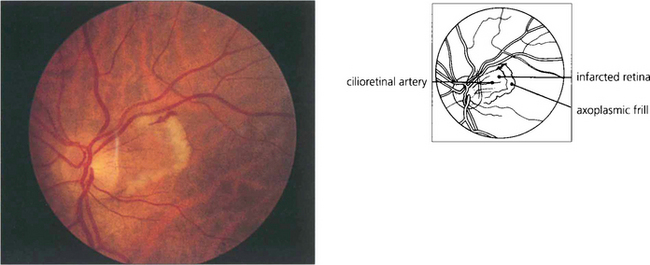

Fig. 14.7 Cilioretinal infarction with central retinal artery sparing is the converse situation to that shown in Fig. 14.5. Here, a small cilioretinal branch is occluded, thus infarcting the retina temporal to the optic disc. A frill of axoplasmic material from the viable retina is seen surrounding the cilioretinal infarct. Cilioretinal infarcts have a similar aetiology to anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, temporal arteritis, which although it usually presents with more extensive disc infarction, must be excluded as a potential cause.

RETINAL EMBOLI

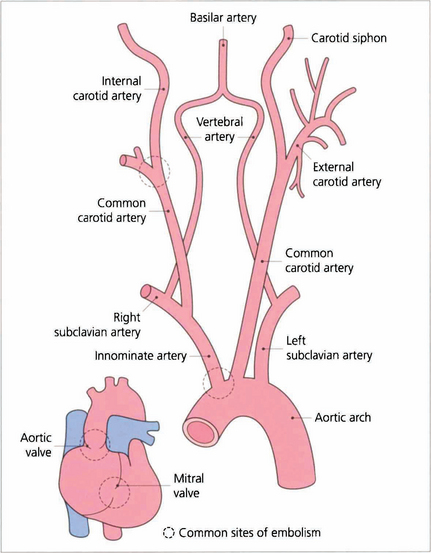

Embolization of the retinal circulation usually occurs with cholesterol or fibrin and platelet emboli from the carotid arteries, or calcific fragments from a stenosed aortic valve. Occasionally more exotic material such as talcum powder in drug addicts or fat emboli in patients with multiple fractures can be seen. Emboli may produce permanent or transient visual loss; cholesterol emboli are also frequently seen coincidentally on routine examination of an asymptomatic eye. Transient uniocular visual loss is known as amaurosis fugax and is virtually always due to embolization, whether or not emboli are actually seen on examination. Patients typically notice uniocular visual loss starting as a concentric peripheral dimming of vision or a vertical curtain coming over the eye, depending on whether the central retinal artery or a branch retinal artery is affected. Most attacks last for periods of a few minutes but may persist for 2–3 hours before vision quite rapidly returns to normal. Attacks may happen singly or in groups, sometimes occurring in clusters or showers during a day. Patients with retinal embolization have an increased risk of developing a permanent stroke over the next few months and the risk is substantially increased if the amaurosis fugax is accompanied by signs of transient cerebral ischaemia or an embolus is visible in the retina. This means that the ophthalmologist plays an important role in the management of these patients by referring them for prophylactic medical or surgical treatment to forestall the development of permanent neurological sequelae. In young patients, mitral valve prolapse or cardiac septal defects can present as amaurosis fugax. Migraine is another rare cause in young adults and may produce transient visual loss by affecting either the retinal or the choroidal circulation. The features are often atypical and more common causes need to be excluded before a diagnosis is made. Choroidal migraine produces patchy visual loss, rather like pieces missing from a jigsaw puzzle, due to involvement of the choroidal lobular circulation (see Ch. 9).

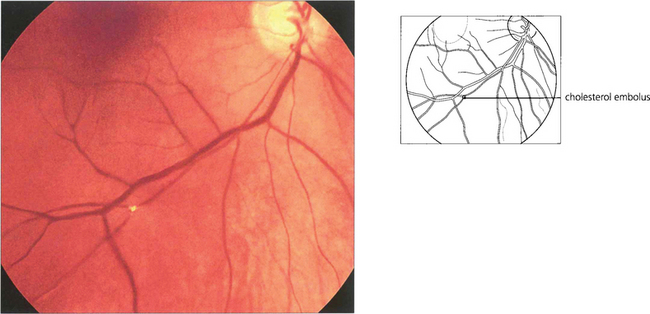

Fig. 14.8 Cholesterol crystals are seen frequently as a coincidental finding in elderly patients and are a sign of atheromatous disease in the carotid circulation (usually at the bifurcation of the common carotid). They are flat crystals that glint and reflect light as the ophthalmoscope is tilted to examine the fundus and are most commonly found at bifurcations of the retinal arteries. Because of the planar shape of the crystal, blood flow may not be disturbed and the patient does not complain of any symptoms. Cholesterol emboli are also known as ‘Hollenhorst’ plaques after the Mayo Clinic ophthalmologist who made the first description.

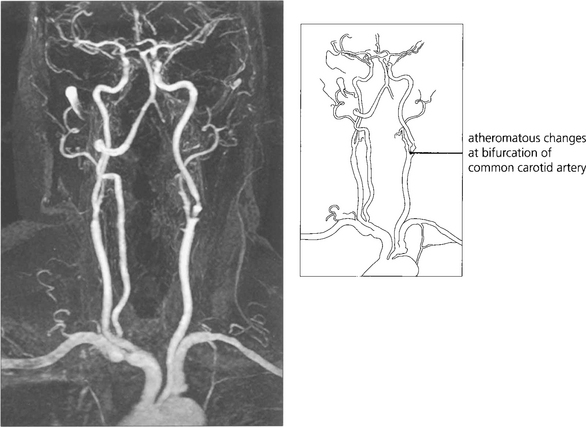

Fig. 14.9 Cholesterol emboli usually arise at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, less frequently at the origin of the great vessels. Calcific emboli usually arise from the aortic valve or ascending aorta.

Fig. 14.10 If the patient is likely to be a candidate for vascular surgery, imaging of the carotid bifurcation is indicated to define an atheromatous lesion. This can be done by Doppler ultrasonography or magnetic resonance angiography. These have now superseded formal arterial angiography which carries a significant risk of stroke in its own right. Clinical trials have established that if the patient is fit for surgery, symptomatic stenoses of greater than 70 per cent are best treated by surgical carotid endarterectomy. Milder degrees of stenosis and unfit patients are better treated medically with inhibitors of platelet aggregation.

Fig. 14.11 Lipid deposition may be seen in the retinal arterial wall following vascular endothelial cell damage after embolization. In this patient there is marked yellowish white sheathing at the origin of the superior temporal artery and, peripheral to this, the vessel is thin, attenuated and fibrosed. Collateral vessels can be seen on the retina and the optic disc has sectorial pallor; the patient had a dense inferior nasal arcuate scotoma. Sometimes the lipid deposition occurs at a bifurcation of a major retinal arteriole giving a ‘trouser leg’ pattern of sheathing to the vessel.

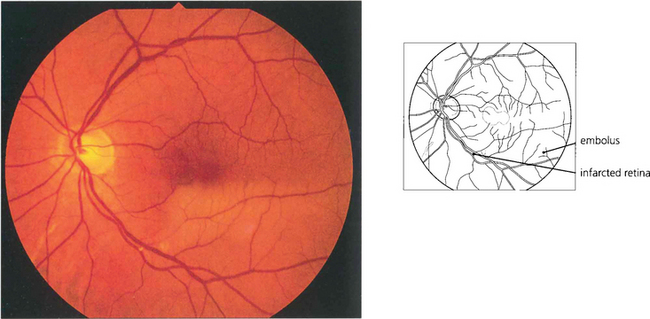

Fig. 14.12 Occlusion of a branch retinal artery is almost always the result of embolization. In this patient with a branch inferior temporal artery occlusion, a small embolus can be seen in the artery at a bifurcation. The embolus is white and globular, unlike a cholesterol embolus, and plugs the vessel. It originated from a stenotic aortic valve.

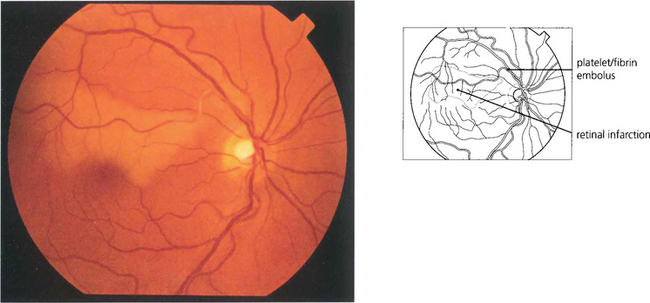

Fig. 14.13 Platelet and fibrin emboli originate from an ulcerating atheromatous plaque and look like soft porridgy material in the vessel. They produce retinal infarction or amaurosis fugax and can sometimes be observed moving slowly through the retinal arterial circulation as the attack evolves. Video fluorescein angiography shows that transient multiple platelet embolization is common during cardiac bypass procedures.

Fig. 14.14 Embolization from fragments of a calcific aortic valve are seen occasionally; their characteristic appearance is different from that of other types of emboli, so aiding their identification. They tend to be larger and globular with a pearly white appearance and lodge in the larger arteries at the optic disc. Echocardiography confirms the diagnosis.

VENOUS OCCLUSIONS

CENTRAL RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION

Elderly patients with central retinal vein occlusion have an increased incidence of arteriosclerosis, smoking, hypertension and diabetes. The role of associated arterial disease in the pathogenesis remains controversial but, as the central retinal artery and vein share a common fascial sheath within the optic nerve, thickening and hypertrophy of the artery can compromise the vein’s diameter leading to obstruction. Patients often notice visual loss on waking with vision having been normal the night before and it has been postulated that lower ocular perfusion due to lower blood pressure and pulse rate and increased intraocular pressure during sleep contribute to this (see Ch. 7). CRVO is also a well recognized association of raised intraocular pressure; this is particularly important to recognize as lowering the IOP in the fellow eye may prevent a subsequent occlusion in this eye.

Although CRVOs are most common in those aged over 60 years, younger patients may also be affected.

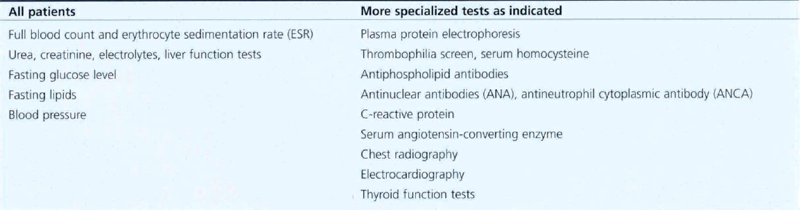

Patients with retinal vein occlusion have an increased incidence of death from cardiac or cerebral causes. Furthermore, there is a 15 per cent risk of recurrence in the same or fellow eye over 5 years. All patients require medical investigation (Table 14.1).

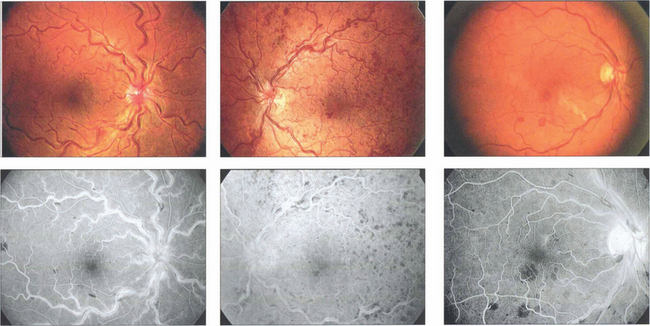

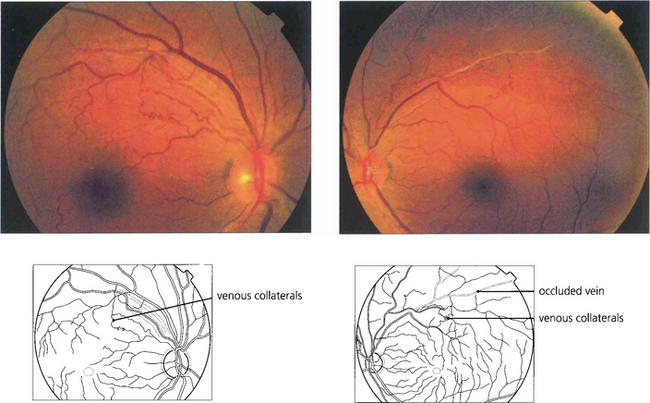

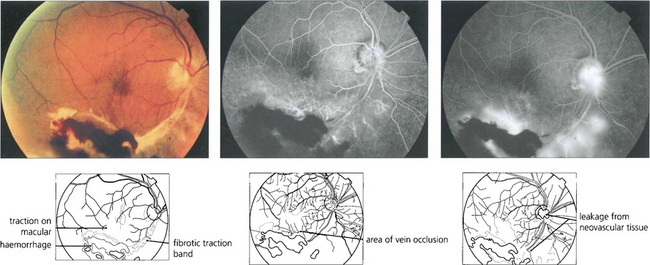

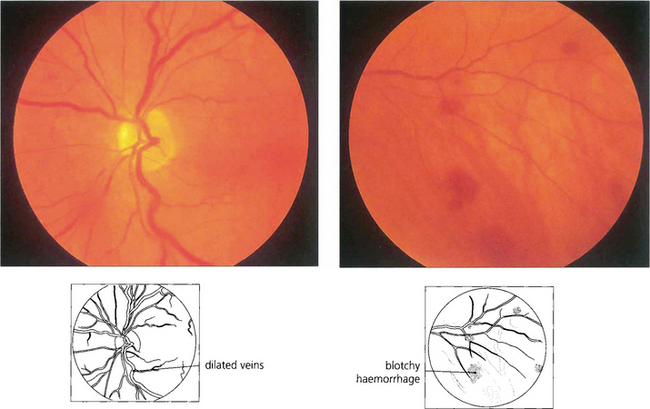

Fig. 14.15 There is a wide range of spectrum appearances which reflect the degree of severity. These eyes show mild venous dilatation and limited fundal haemorrhages. Fluorescein angiography shows venous and capillary leakage on the optic disc and in the retina. Retinal haemorrhages mask the choroidal fluorescence.

Fig. 14.16 Patients with CRVO and macular oedema (left and centre) present with blurring of vision which tends to improve over 3–4 months as the central retinal vein recanalizes or venous collateral vessels develop on the optic disc to the choroidal circulation. At this stage the visual acuity may improve and the retinal haemorrhages and macular oedema absorb. Six months later this patient shows a remarkable improvement with improvement of acuity from 20/60 to 20/30. (right). In more severe cases the macular oedema may persist with consequent visual loss.

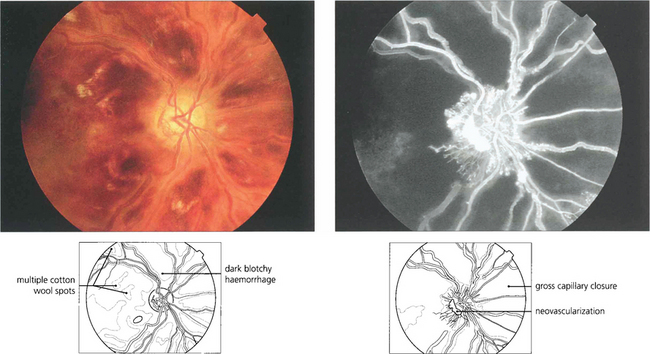

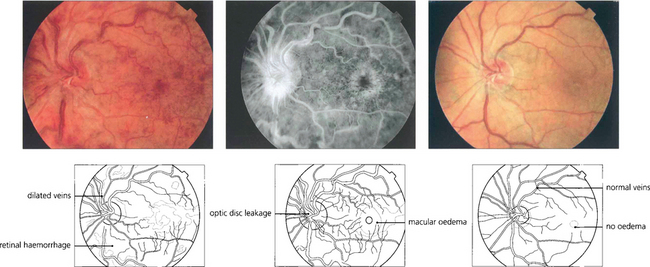

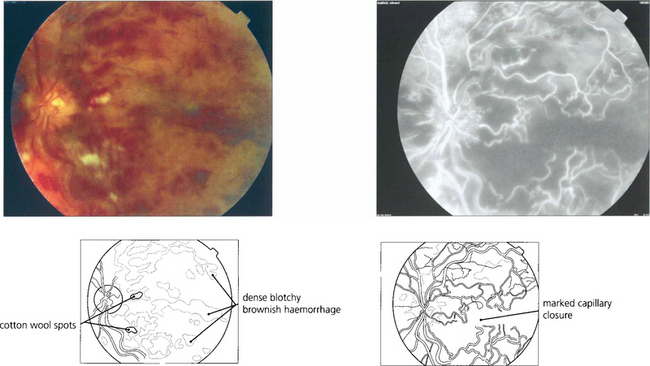

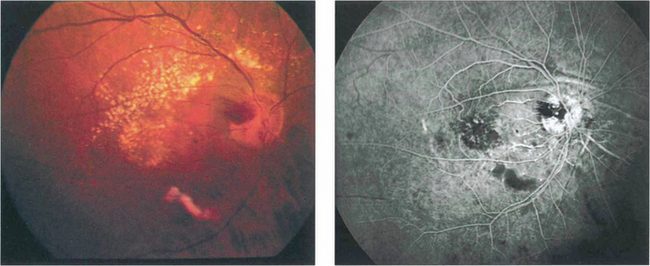

Fig. 14.17 Signs suggestive of retinal ischaemia are dense, dark, blotchy haemorrhages and cotton-wool spots. Retinal haemorrhages make interpretation of the degree of ischaemia difficult in the acute stage as they mask the retinal capillary bed and angiography is more informative if postponed until these have been absorbed. The major vessels fill with dye but there are large areas of capillary nonperfusion. In the later stages there is gross leakage of dye from the major retinal vessels and the optic disc, especially in the ischaemic areas. Surprisingly, marked capillary closure in the posterior pole can sometimes be compatible with reasonable preservation of visual acuity, although the majority of such eyes have extremely poor vision.

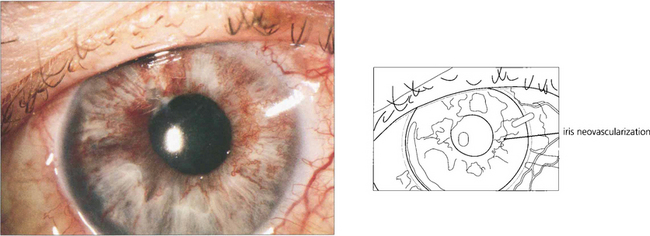

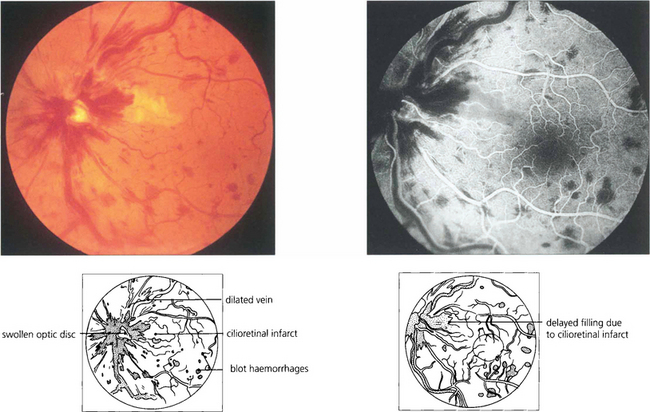

Fig. 14.19 In the presence of gross capillary closure, 30–50 per cent of eyes develop rubeosis iridis and progress to thrombotic glaucoma. Rubeosis iridis classically appears about 3 months after the vein occlusion. In the earliest stages a fine neovascular network is seen around the pupil or the angle of the anterior chamber. This is followed by development of ectropion uveae from contraction of the neovascular membrane, further vascular proliferation, glaucoma and corneal oedema (see Ch. 8). This sequence of events can be forestalled by early panretinal photocoagulation as soon as the new vessels appear on the iris or angle; for this reason patients should be seen every month for 6 months after presentation. After treatment the rubeotic iris vessels will atrophy to leave the patient with an eye that has poor vision but is comfortable. Retinal or optic disc neovascularization is very uncommon after CRVO. Glaucomatous eyes with rubeosis and visual potential may be salvaged by a tube drainage procedure. Blind eyes can be made comfortable by topical steroid and mydriatic therapy but a proportion of these eyes will eventually have to be enucleated as blind painful eyes.

Fig. 14.20 CRVO may produce marked disc swelling that is distinguished from other causes of swollen optic discs by the presence of haemorrhages in the peripheral retina in all four quadrants. Some of these patients may develop concomitant cilioretinal artery occlusion. The perfusion pressure of the ciliary circulation is lower than that of the retinal circulation and the raised venous pressure increases the retinal perfusion pressure above that of the ciliary circulation causing infarction. This patient presented with mild blurring of vision that resolved, leaving a small centrocaecal scotoma.

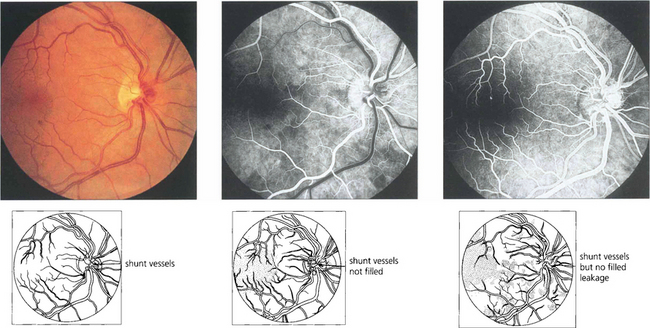

Fig. 14.21 This eye shows collateral opticociliary shunt vessels on the optic disc as evidence of a previous resolved CRVO. These are derived from normal vessels and shunt blood from the obstructed retinal venous circulation to the unobstructed choroidal circulation with outflow through the vortex veins. The collateral vessels do not leak fluorescein, in contrast to neovascularization, because they are derived from normal vascular channels with tight endothelial cell junctions.

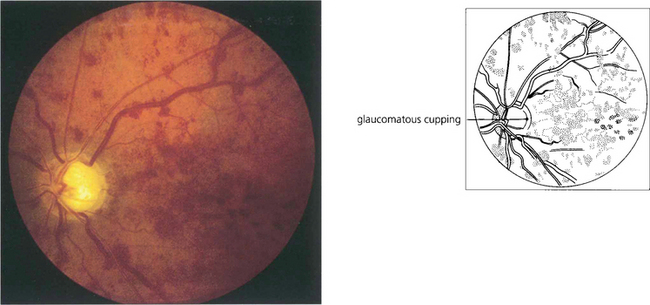

Fig. 14.22 CRVO is common with glaucoma. The IOP and optic disc of the fellow eye must be checked carefully in any patient with CRVO as this may become the patient’s only functioning eye. In many patients with glaucoma the CRVO is subclinical, indicated only by the presence of shunt vessels as a coincidental finding (see Ch. 7).

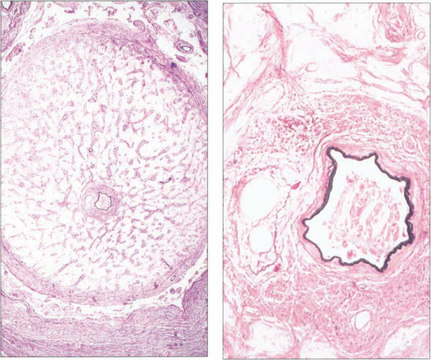

Fig. 14.23 The optic nerve of a patient whose eye was enucleated for thrombotic glaucoma shows gliosis and atrophy of the nerve (compare with the normal nerve see Ch. 17). The common fascial sheath of the central retinal artery and vein is demonstrated; the artery is identified by its muscular wall. A thrombus containing cholesterol crystals is lodged in the arterial lumen, the vein is pushed to one side, and there is recanalization with multiple channels.

BRANCH RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION

Occlusion of branch retinal veins produces a similar fundus picture to that of central vein occlusion but limited to the affected area. Most branch vein occlusions occur in the temporal retina at arteriovenous crossings in patients with systemic hypertension or arteriosclerosis. Thickening of the artery leads to compression of the underlying vein within the shared fascial sheath. Branch vein occlusions at other sites may occur from an inflammatory phlebitis (see Ch. 10), with diabetes or occasionally at the rim of a deeply cupped glaucomatous optic disc where the vein bends over the rim.

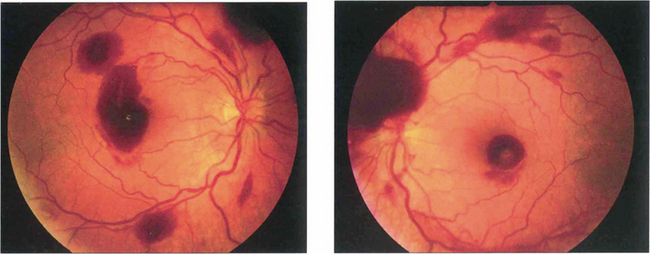

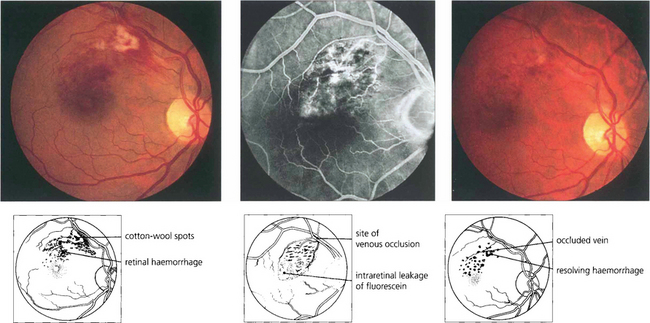

Fig. 14.24 A small macula branch vein occlusion is seen in a hypertensive patient who presented with blurred vision. Fluorescein angiography shows the site of occlusion at an arteriovenous crossing with retinal vascular leakage, haemorrhage and oedema in the affected area. Some weeks later the haemorrhage can be seen to be resolving with corresponding improvement in vision.

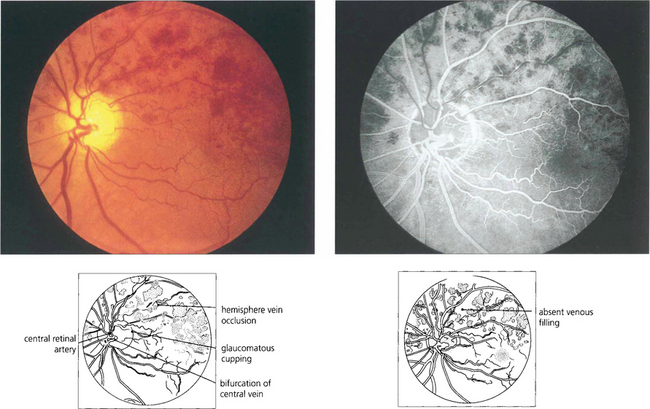

Fig. 14.25 In some patients the central retinal vein divides within the disc and a major branch can be occluded within the disc, producing a hemisphere venous occlusion analogous to a central vein occlusion.

Sequelae of branch retinal vein occlusion

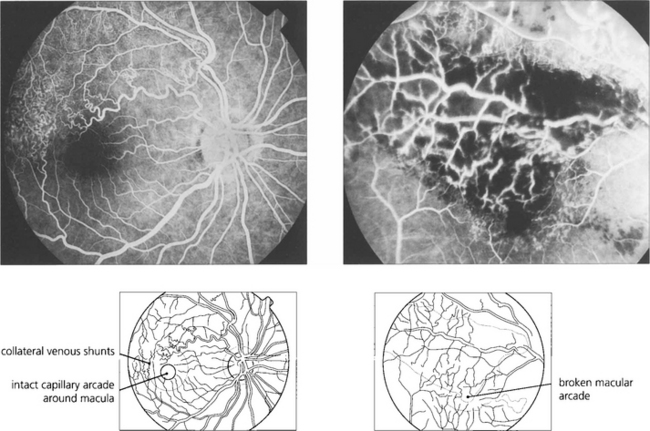

Fig. 14.26 If the capillary vascular arcade surrounding the fovea is broken the prognosis for visual recovery is poor.

Fig. 14.27 Following a branch vein occlusion collaterals may develop shunting venous drainage to the healthy circulation. These vessels resemble venous collaterals on the optic disc in that they are derived from normal capillaries and do not leak fluorescein or produce ocular morbidity.

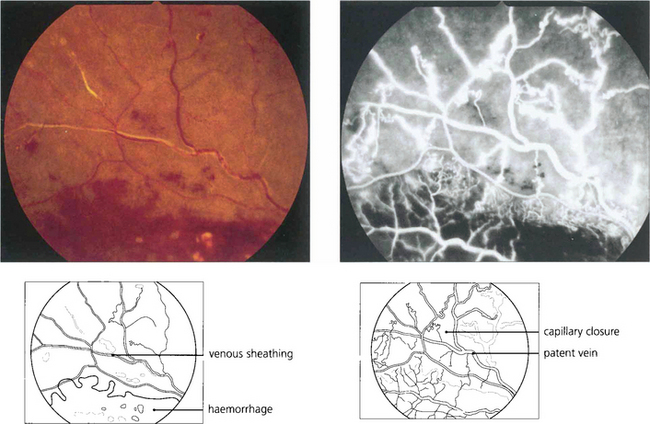

Fig. 14.28 Major retinal arteries or veins that pass through an area of hypoxic retina may become white and sheathed with fibrosis and lipid deposition in the vascular walls. These photographs show a superior temporal vein occlusion with dense dark haemorrhages and cotton-wool spots indicating retinal ischaemia. The vein within the ischaemic retina has become white and sheathed. Angiography shows considerable capillary closure but the vein is still patent. Such sheathing must be distinguished from the whiter, more ill-defined and fluffy appearance of retinal periphlebitis (see Ch. 10).

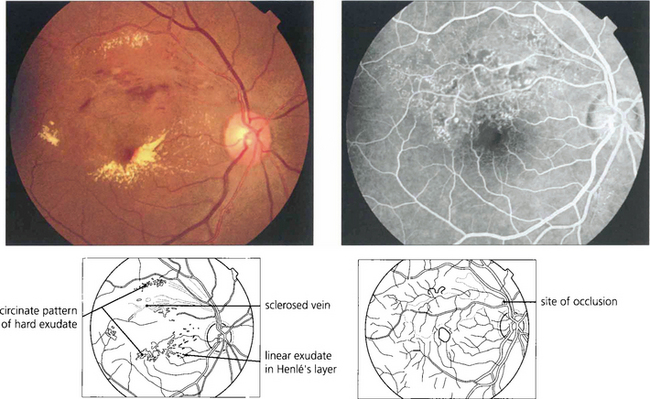

Fig. 14.29 Visual loss in the acute stages of BRVO is due to involvement of the macula by haemorrhage, oedema or ischaemia. Vision may improve as these changes resolve over weeks or months and if the capillary arcade surrounding the macula is left intact the visual prognosis is comparatively good. Persistent visual loss may be caused by ischaemic macula damage, epiretinal membrane formation or chronic macula oedema. Lipid exudation sometimes occurs some months after the initial occlusion and produces further deterioration of visual acuity. This patient shows hard exudate and macula oedema extending into the viable inferior retina from a superior temporal BRVO. Angiography demonstrates marked capillary dilatation and leakage in the area of the previous occlusion. If this area is photocoagulated, the lipid will slowly be absorbed and further visual loss will be prevented.

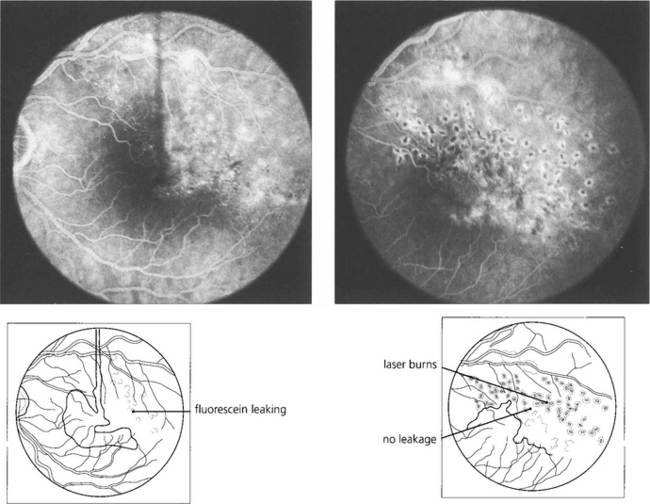

Fig. 14.30 This patient has chronic macular oedema following a superior temporal vein occlusion. Following photocoagulation to the affected area the oedema resolved as did the visual improvement.

Fig. 14.31 Severe branch vein occlusion with capillary closure may be followed by retinal neovascularization, usually at the junction of ischaemic and healthy retina. There must be at least a quadrant of closure and commonly neovascularization takes about 6 months to develop. These vessels readily regress following photocoagulation of the hypoxic retina. Rubeosis iridis is uncommon but when it does occur it hardly ever progresses to thrombotic glaucoma. This patient shows a fibrovascular membrane with preretinal haemorrhage and traction on the macula following an inferior branch retinal vein occlusion 6 months earlier. Angiography demonstrates the venous occlusion and neovascularization in the scar and on the disc. Following vitrectomy, membrane peeling and photocoagulation, acuity remained unchanged at counting fingers although distortion improved to some extent.

SLOW FLOW RETINOPATHY (OCULAR ISCHAEMIC SYNDROME)

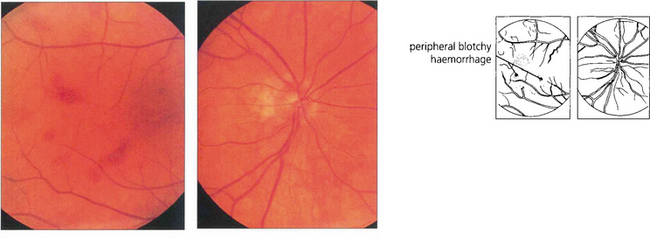

Fig. 14.32 This 58-year-old man was a heavy cigarette smoker with diabetes who presented with transient blurring of vision in the right eye. Ophthalmoscopy showed mildly dilated retinal veins with peripheral haemorrhages. The central retinal artery collapsed with the slightest digital pressure on this globe.

Fig. 14.33 Fluorescein angiography showed prolonged slow filling of both the choroidal and retinal circulations with diffuse leakage from small vessels in the posterior pole and microaneurysms and haemorrhages in the periphery in the later phases. Magnetic resonance angiography showed that both vertebral arteries and the right common carotid were completely occluded. A Doppler study showed reversal of flow in the ophthalmic artery, indicating that there was intracranial supply from the external carotid artery.

HYPERVISCOSITY SYNDROMES

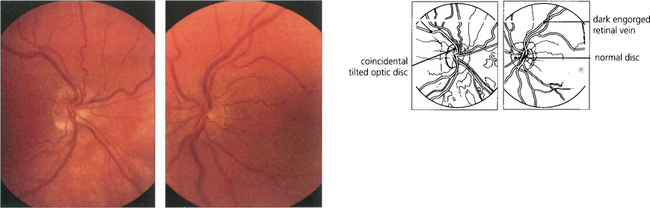

Fig. 14.34 This patient with primary polycythaemia rubra vera shows dilatation of the retinal vessels with no other signs of retinal ischaemia. The haemoglobin concentration was 23 g/l. The patient complained of mild blurring of vision which improved rapidly following venesection.

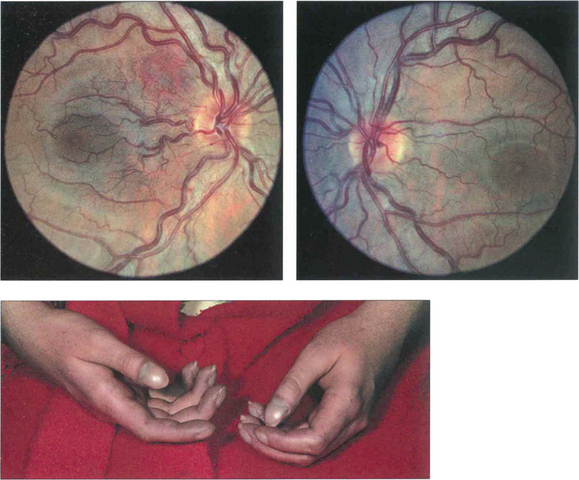

Fig. 14.35 This patient had the congenital cardiac defect of Fallot’s tetralogy. She has peripheral cyanosis, clubbing and cyanosed retinal vessels.

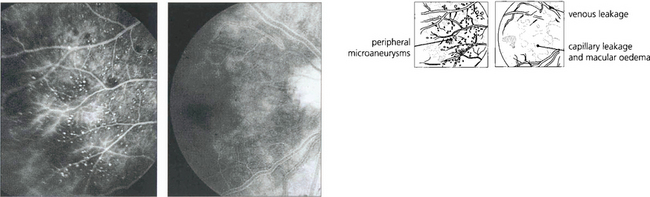

Fig. 14.36 This patient had Waldenstrõm’s macroglobulinaemia with extremely high plasma viscosity, haemoglobin concentration of 8.9 g/l, and a platelet count of 120000. The retinal veins are mildly engorged and peripheral haemorrhages are present.

HYPERTENSIVE RETINOPATHY

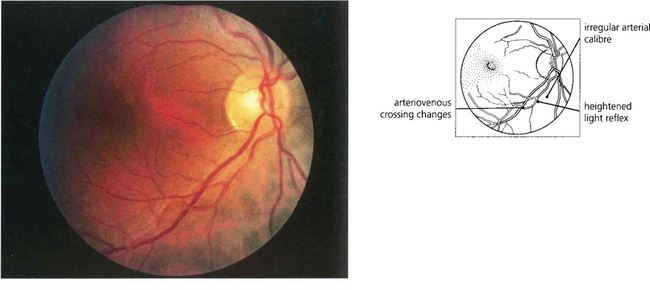

Fig. 14.39 This photograph illustrates the fundus appearance of a 40-year-old black patient with systemic hypertension of relatively short duration. The inferior temporal artery has an irregular calibre and increased light reflex from the vessel wall and there is pronounced arteriovenous nipping where the vessels cross. Although these changes are pathological in a young patient it would be more difficult to say with certainty that they were so in an elderly patient.

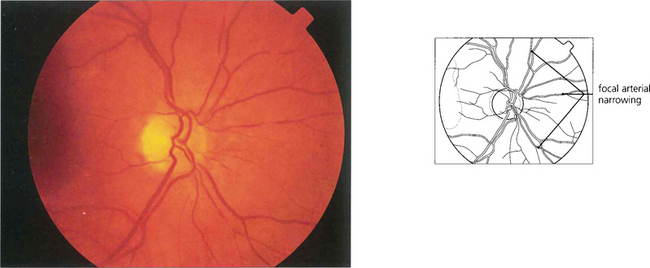

Fig. 14.40 Narrowed arterioles with focal attenuation can be seen in the fundus of this 55-year-old seaman. The blood pressure was normal indicating that these are arteriosclerotic rather than hypertensive changes.

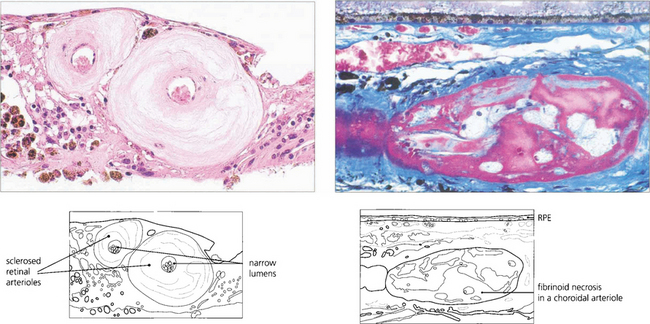

Fig. 14.41 In arteriolosclerosis (left) the smooth muscle of the vessel wall is replaced by collagen with narrowing of the lumen; (right) shows fibrinoid necrosis in a choroidal arteriole.

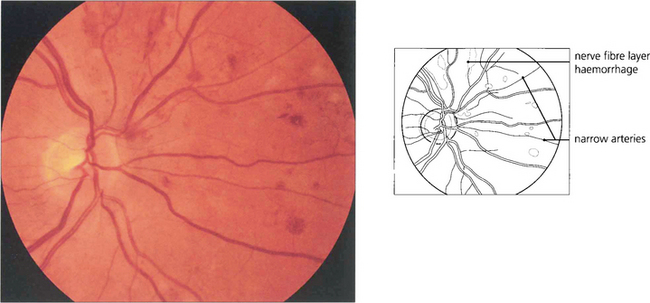

Fig. 14.42 Retinal haemorrhages, particularly in the superficial retina (flame-shaped) are a feature of chronic severe hypertension.

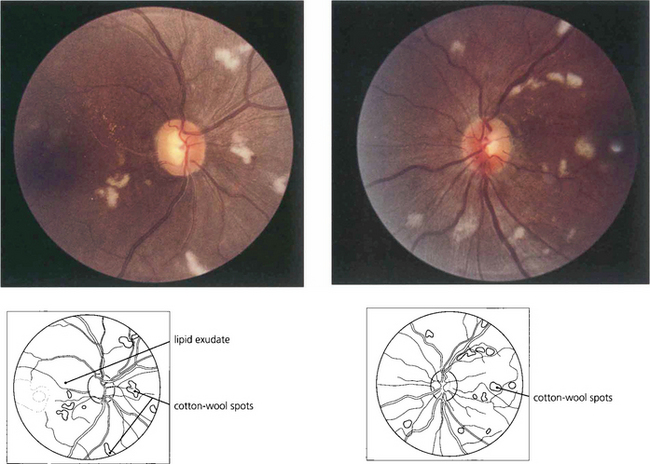

Fig. 14.43 Bilateral optic disc swelling or the sudden appearance of cotton-wool spots with hypertensive retinopathy is known as accelerated hypertension. The prognosis is very poor if the blood pressure is not rapidly controlled to prevent cardiac failure and hypertensive encephalopathy. This patient has acute hypertension of rapid onset and multiple cotton-wool spots in each eye. The main retinal arteries are comparatively spared, indicating the acuteness and severity of the hypertension.

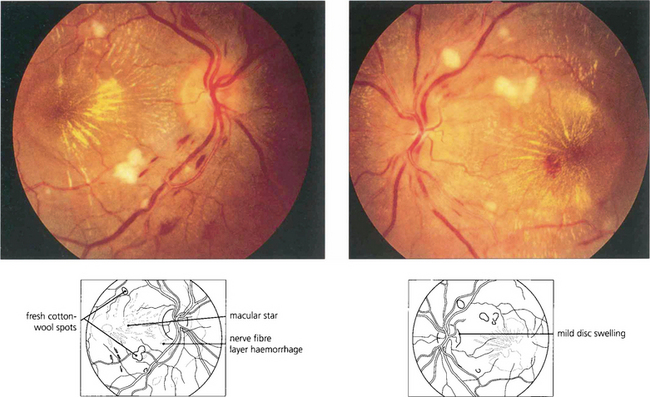

Fig. 14.44 This patient shows mild disc swelling in the left eye, cotton-wool spots, retinal haemorrhages and macular stars, indicating severe systemic hypertension. Macula stars suggest that the disc swelling has a vascular aetiology, commonly hypertensive or ischaemic; they usually appear as the disc swelling resolves.

Fig. 14.45 Swelling of the optic disc with accelerated hypertension probably results from local tissue ischaemia rather than raised intracranial pressure, which is usually normal. Visual acuity remains normal in the absence of macula changes.

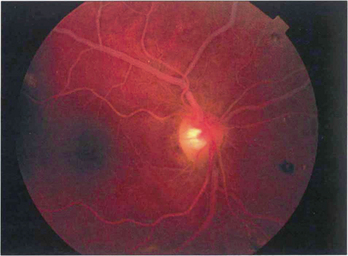

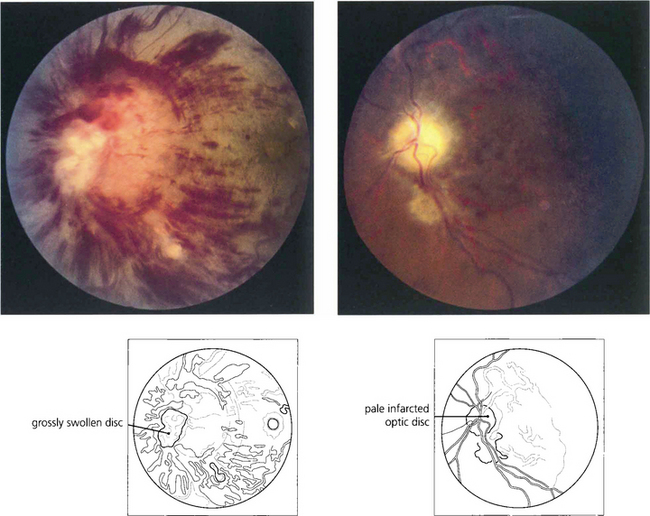

Fig. 14.46 The blood pressure requires urgent control but this must be done cautiously as a sudden drop in tissue perfusion pressure can cause infarction of the optic disc. This patient presented with blurred vision, a blood pressure of 210/130 mmHg and bilateral disc swelling. Over-enthusiastic control resulted in bilateral optic disc infarction and blindness of both eyes.

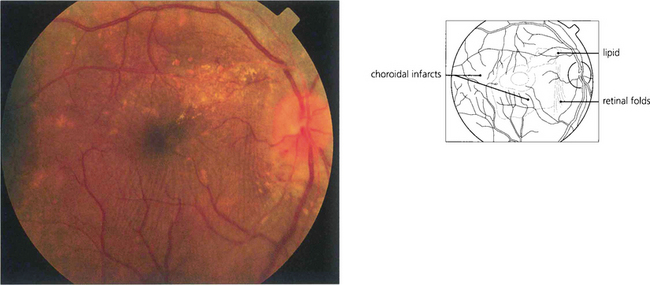

Fig. 14.47 Changes in the choroidal vasculature with hypertensive retinopathy do not usually affect vision but bullous serous retinal detachments can be seen with very severe acute systemic hypertension as a result of infarction of the choriocapillaris and breakdown of the outer blood–retina barrier. Elschnig’s spots represent foci of infarction of the choriocapillaris in the posterior pole with overlying changes in the retinal pigment epithelium (see Ch. 9).

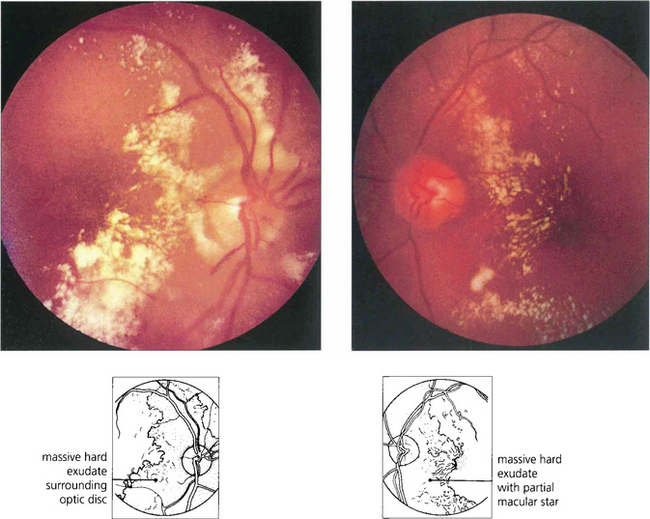

Fig. 14.48 Hypertension with renal failure can produce a much more exudative pattern of retinopathy with less evidence of retinal ischaemia. Following control of blood pressure and renal dialysis in this patient the retinal exudate was absorbed over several months and visual acuity returned to normal.

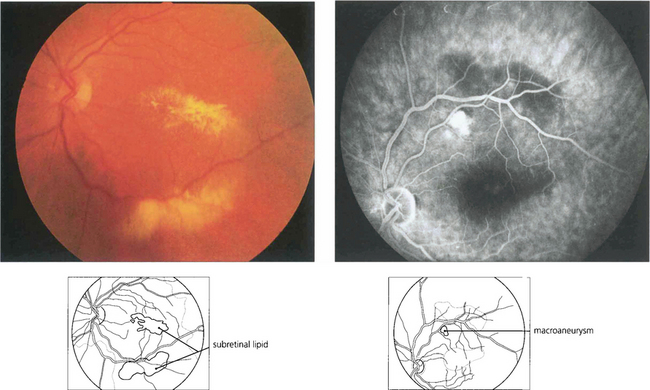

RETINAL MACROANEURYSMS

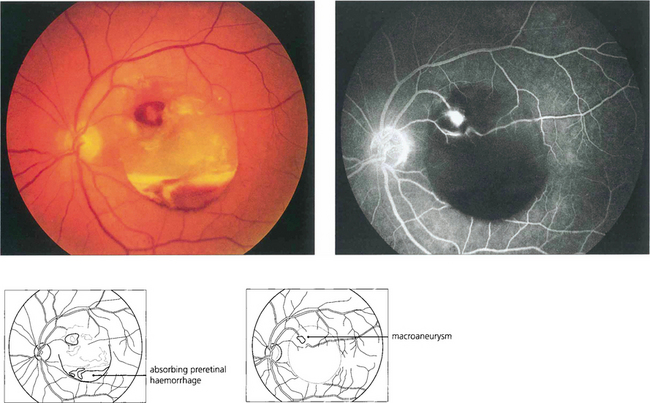

Macroaneurysms of the retinal arterioles are usually seen in elderly patients with systemic hypertension; they are similar in pathology to the Charcot–Bouchard aneurysms of the cerebral circulation which are thought to be due to embolization with damage to the arterial wall. Retinal macroaneurysms tend to occur at the branching points of second or third order arterioles. They may be found either coincidentally or because they cause visual disability due to haemorrhage or leakage of lipid and macula oedema. Studies have shown that the haemorrhagic complications resolve spontaneously and do not require specific treatment but that exudative changes should be treated by photocoagulation as they may damage the fovea producing permanent visual loss. Retinal macroaneurysms must be distinguished from Leber’s miliary aneurysms (see Ch. 15) or vascular anomalies due to venous occlusions or diabetes.

Fig. 14.49 This patient has a localized posterior vitreous separation and preretinal haemorrhage from a macroaneurysm. The haemoglobin is being absorbed from the haemorrhage leaving white erythroclastic ghost cells. Macroaneurysms can often be difficult to identify by ophthalmoscopy but are readily demonstrated by fluorescein angiography. The haemorrhage masks the background choroidal fluorescence and the aneurysm is seen as a hyperfluorescent saccular dilatation of the artery—the ‘light bulb’ sign.

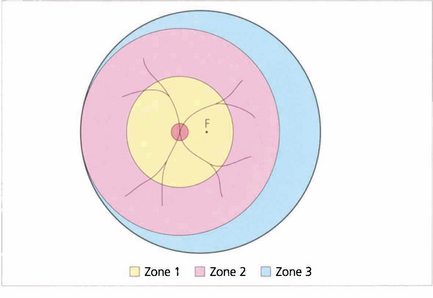

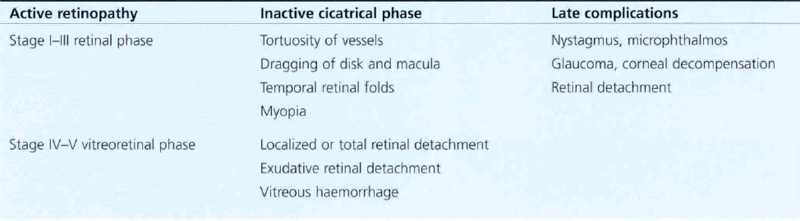

RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY

STAGING AND INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION

The goal of screening is to identify and treat ‘threshold’ ROP. This is defined as disease at stage III (ridge with extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation) that involves zone 1 or 2 over five contiguous or eight cumulative clock-hours or the presence of ‘plus’ disease in which the arterioles are tortuous and veins engorged in the posterior pole. Argon laser photocoagulation with the indirect ophthalmoscope of the peripheral nonperfused retina should be undertaken in infants with ‘threshold’ disease as these babies have a high risk of developing cicatricial retinal detachment. Effective and economical screening can be achieved by limiting screening to infants with a gestational age of 33 weeks or less and weighing less than 1500 g. All such babies are examined at 6–8 weeks after birth and again at a gestational age of 36 weeks. Most cases of ROP develop between 32 and 44 weeks, and stage 3 occurs between 34 and 42 weeks; the more posterior (zone 1 or 2) the involvement, the more rapid and severe is the development. ROP that develops after 36 weeks is unlikely to reach stage 3, as is ROP developing in zone 3.

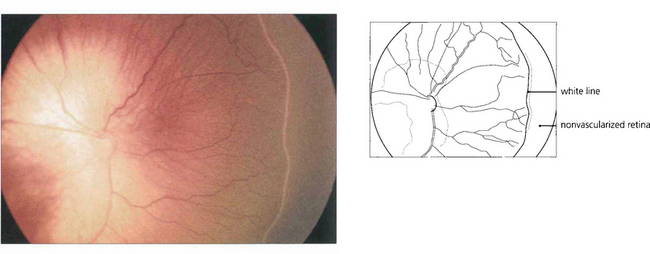

Fig. 14.52 In this baby with stage I ROP there is a thin white demarcation line between vascularized and nonvascularized nasal retina, signifying the onset of disease. This occurs at a gestational age of approximately 32 weeks in the majority of cases.

By courtesy of Mr P Watts.

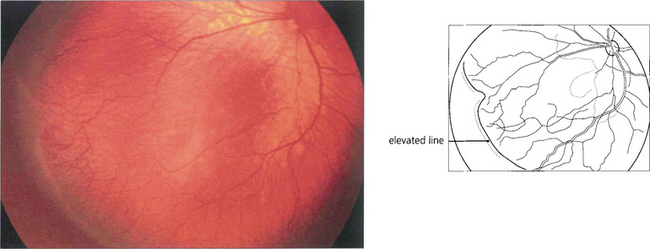

Fig. 14.53 In stage II the retinal lesion acquires volume and projects out of the retinal plane.

By courtesy of Mr P Watts.

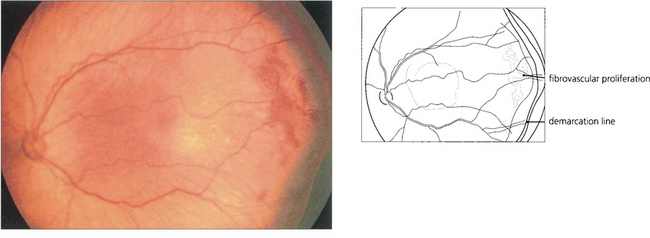

Fig. 14.54 Stage III occurs at about 36 weeks of gestational age. There is extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation from the posterior edge of the ridge or posterior to it which projects into the vitreous, which may be either segmental or continuous.

By courtesy of Mr P Watts.

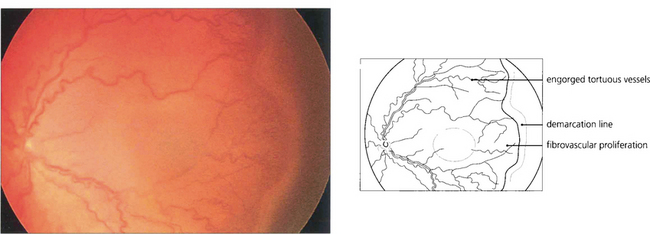

Fig. 14.55 ‘Plus’ disease indicates activity. There is engorgement and increased tortuosity of the retinal vessels in the posterior pole, iris vessel engorgement, pupil rigidity and vitreous haze. This stage is of great clinical importance as it precedes the onset of vitreoretinal disease, which may be prevented by timely intervention. Severe ROP tends to progress rapidly and the window for therapeutic intervention is short—about 2 weeks.

By courtesy of Mr P Watts.

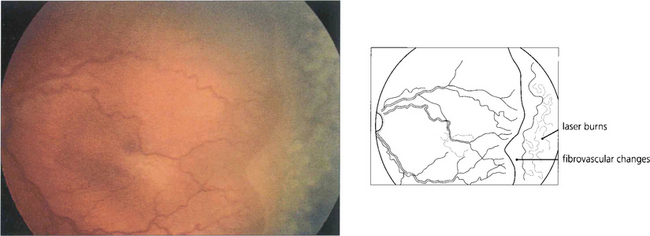

Fig. 14.56 Regression after laser photocoagulation is characterized by decreased congestion and tortuosity of the retinal vasculature; formation of a brush border at the demarcation line; and a change in colour of the stage III retinal lesion from salmon pink to red as the retinal lesion becomes more differentiated into a fibrovascular component and finally into white scar tissue.

By courtesy of Mr P Watts.

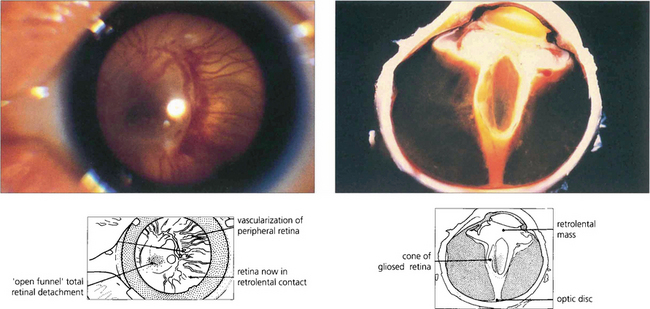

Fig. 14.57 The onset of vitreoretinal disease (stages IV and V) is signified by the sudden onset of a secondary vitreous haze in the presence of stage III disease. With the onset of stage IVa (subtotal extrafoveal detachment) and IVb (with foveal detachment), retinal ablation becomes ineffective and traction retinal detachment usually follows within 1 week. Progression to total retinal detachment (stage V) usually occurs approximately at term, producing a vascularized white retrolental mass that must be differentiated from other causes of leucocoria in an infant (e.g. retinoblastoma, congenital cataract, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, retinal colobomas or folds and endophthalmitis).

By courtesy of Dr B Fantl.

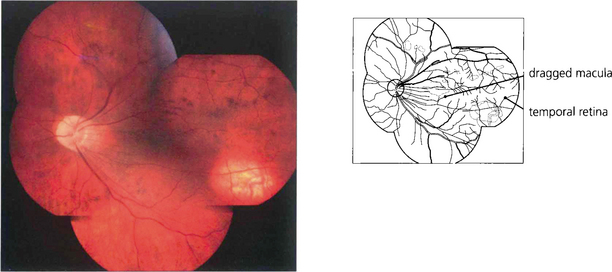

Fig. 14.58 Late cicatricial changes in eyes with vitreoretinopathy produce dragging of the macula and temporal vessels towards the temporal periphery. Such eyes usually have poor vision and nystagmus and may develop cataracts or retinal detachment from peripheral lattice degeneration and hole formation in early adult life.

By courtesy of Mrs R Zakir.

TRAUMATIC RETINOPATHY

The retina can be damaged by excessive exposure to light, ionizing radiation or by contusion injury. Retinal tears and perforating injuries are discussed in Chapter 12 and drug toxicity in Chapter 15.

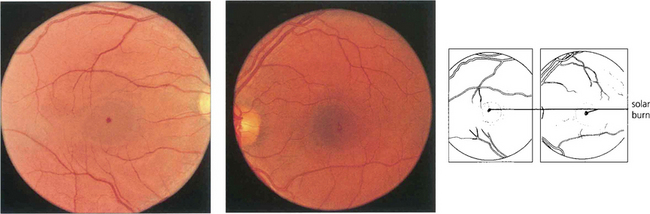

Fig. 14.59 Solar burns are seen as minute central macular pits in the inner retina often just adjacent to the fovea in patients with a history of sun-gazing, as in this LSD user. They probably result from uptake of blue light by the macular yellow xanthophil pigment. Visual acuity is often quite good (from 20/30 to 20/40). Findings on fluorescein angiography are normal. Similar lesions are occasionally seen in patients with no obvious history of solar exposure.

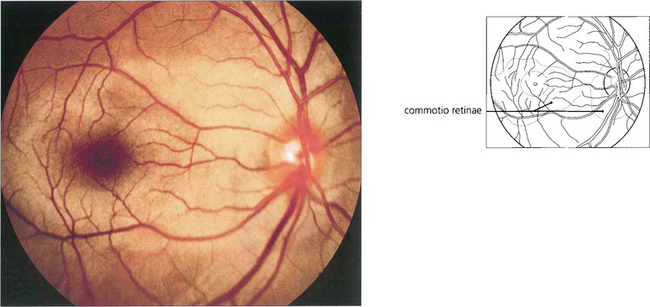

Fig. 14.60 Retinal oedema is a common finding following a blunt injury to the eye (sometimes called commotio retinae, Berlin’s oedema). Any part of the fundus can be affected. The area appears pale with a silvery sheen due to intraretinal oedema of the outer retina. This usually resolves over a few days without sequelae, although a careful examination of the retinal periphery for a dialysis or break must be made (see Ch. 12). The possibility of traumatic anterior chamber angle recession and future cataract must not be overlooked.

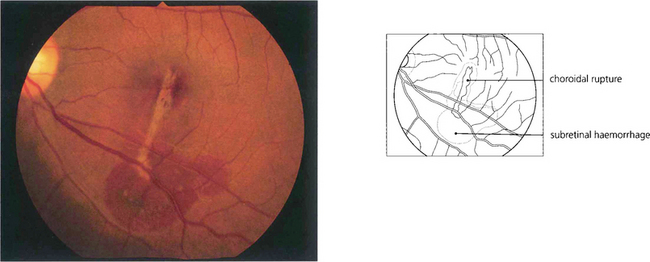

Fig. 14.61 More severe blunt trauma may produce a ‘choroidal’ rupture affecting the choroid, Bruch’s membrane and retinal pigment epithelium but not the relatively elastic retina (these patients are susceptible to later development of subretinal neovascularization if the injury affects the macular area; see Ch. 16).

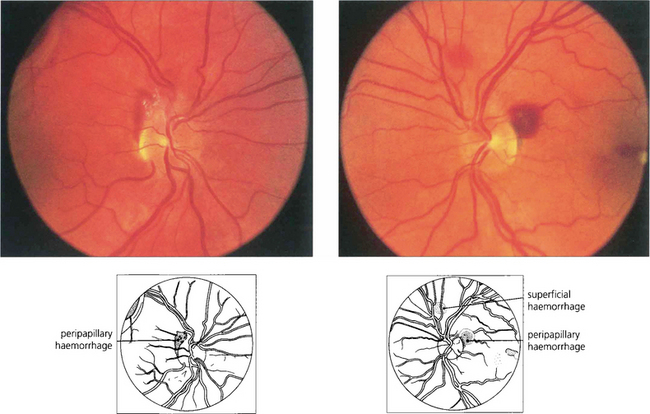

Fig. 14.62 Terson’s syndrome. Preretinal haemorrhages from an acute rise in venous pressure can be seen as a result of subarachnoid haemorrhage, strangling or a sudden Valsalva manoeuvre. Severe cases can produce intragel vitreous haemorrhage. This patient was a 37-year-old woman who developed the retinopathy following a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

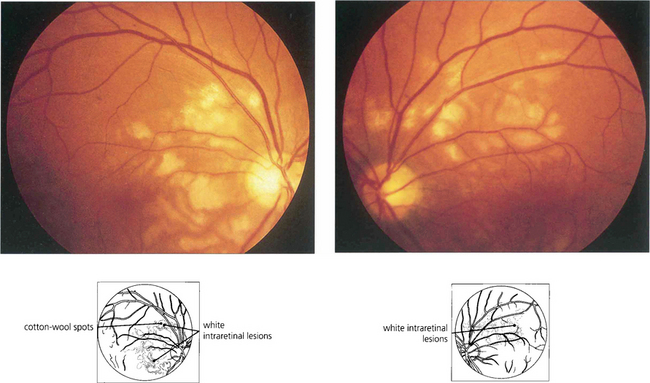

PURTSCHER’S RETINOPATHY

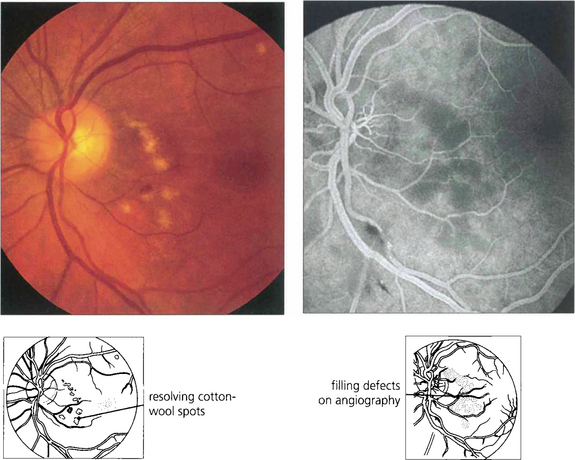

Fig. 14.63 These photographs were taken 3 weeks after a severe road traffic accident in which the patient suffered fractures to the left femur and humerus and a crush injury to the chest from the seat belt. The patient complained of dimness of vision in this eye and patchy visual loss that made reading difficult although he could still read J3. Some months later there was disc pallor, arterial attenuation and extensive nerve fibre loss. The symptoms remained unchanged and the fellow eye was normal.

RADIATION RETINOPATHY

Fig. 14.65 This patient received radiotherapy for an ethmoidal sinus tumour and presented 18 months later with an acuity of counting fingers. Colour images show a localized area of ischaemia in the posterior pole that was inadvertently covered in the radiation field. Fluorescein angiography demonstrates the area of ischaemia and leakage which does not correspond to an anatomical vascular distribution. The eye eventually developed rubeotic glaucoma and became totally bind.