Chapter 5 The respiratory system

Development of the respiratory system

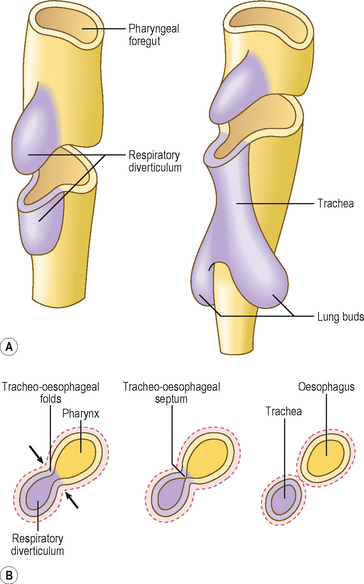

The epithelial component of the respiratory system (including that of the larynx, trachea, bronchi and lungs) develops from the ventral wall of the endodermal lining of the foregut as an outpouching, which grows into the surrounding splanchnopleuric mesoderm as primitive connective tissue surrounding the endodermal respiratory diverticulum (Fig. 5.1A). The same splanchnopleuric mesoderm also gives rise to the visceral pleura, cartilage, smooth muscle and blood vessels of the lower respiratory tract. The respiratory diverticulum develops at the junction between the cranial and caudal foregut. This diverticulum soon separates from the foregut by the development of bilateral longitudinal ridges, the tracheo-oesophageal folds, that fuse together to form the tracheo-oesophageal septum. This septum separates the ventral trachea from the dorsal oesophagus (Fig. 5.1B). Thus, the pharynx communicates with the larynx via the future laryngeal inlet.

The larynx is lined by epithelium derived from the endoderm, whereas the cartilages and muscles of the larynx arise from the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches (see Chapter 11).

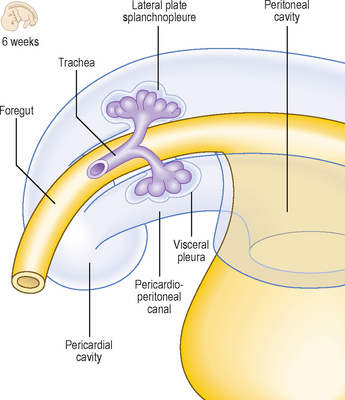

The lung buds are the paired structures that develop from a single midline outpouching, the respiratory diverticulum (Fig. 5.1A). Each lung bud divides many times to form the bronchial tree. The process by which the division of the airways is accomplished is known as branching morphogenesis and it is regulated by a variety of molecular signals. There are differences on the two sides: the right lung bud divides into three secondary bronchial buds, forerunners of the three lobes, whereas the left lung bud gives rise to two secondary bronchial buds, to become the two lobes on the left. Thus, a series of rapid further divisions of the airways takes place, penetrating the surrounding splanchnopleuric mesoderm and bulging into the coelomic cavity at the pericardioperitoneal canals (Chapter 3). These two canals are destined to become the right and left pleural cavities, and they lie on either side of the foregut (Fig. 5.2). The pericardial cavity (see Chapter 6) is separated from the primitive pleural cavities by the pleuropericardial folds on each side. The peritoneal cavity is separated from the pleural cavities by the pleuroperitoneal membranes (see Chapter 3). Whilst the splanchnopleuric mesoderm forms the visceral layer of the pleura, the somatopleuric mesoderm lines the thoracic walls and thus forms the somatic layers of the pleura.

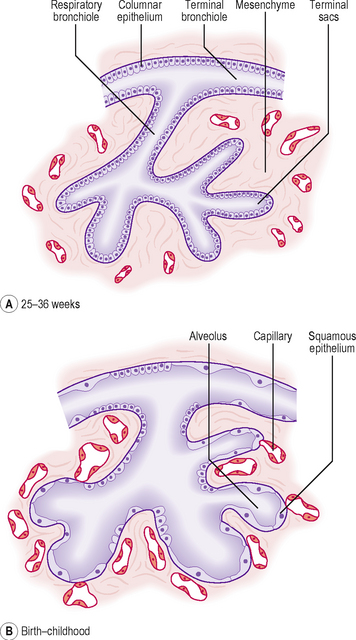

The maturation of the lungs occurs in phases. These different phases are not important other than to appreciate the changes which the lungs undergo. Initially, the lungs are glandular structures histologically, but over time the epithelium thins and tubes or canals form. This is followed by the development of primitive alveoli (Fig. 5.3).

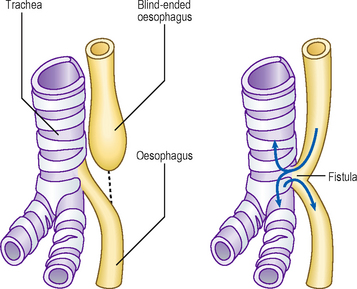

A number of malformations can arise because of incomplete separation of the oesophagus and the trachea (Fig. 5.4). The danger of such malformations in an infant is that swallowed fluids could enter the respiratory tract. The oesophagus can end blindly and not continue with the distal gut tube, leaving a connection with the respiratory tract and the distal gut tube. This is known as a tracheo-oesophageal fistula and is usually associated with oesophageal atresia. This leads to abnormal circulation of the amniotic fluid because the fetus normally swallows the fluid and it expels the same volume into its urine. In the presence of a tracheo-oesophageal fistula, the volume of amniotic fluid increases within the amniotic sac, polyhydramnios, and an enlarged uterus results. The affected oesophagus may be surgically re-attached to the distal gut tube. These abnormalities arise because of the failure of the tracheo-oesophageal septum to form properly. If the division of the lung buds fails to occur properly the lungs will be smaller than normal, a condition known as pulmonary hypoplasia. Unilateral agenesis is also possible so that the lung fails to form on one side.

Respiration is not possible until the cuboidal epithelium of the canals has thinned sufficiently. During this period capillaries come into contact with the thinning epithelial wall and establish the possibility of respiratory gaseous exchange. This begins from about the seventh month. The cells lining the sacs become the alveolar type I cells. Type II surfactant-producing cells appear from about 6 months of age. Surfactant, a phospholipid, reduces the surface tension at the air–fluid interface in the alveoli and this helps the air spaces to inflate.

The respiratory system develops from two germ layers. The epithelial lining arises from the endoderm, which forms the lining of the foregut tube.

The respiratory system develops from two germ layers. The epithelial lining arises from the endoderm, which forms the lining of the foregut tube. A small diverticulum buds off the ventral surface of the foregut to form the lung bud. This grows into the splanchnopleuric mesoderm, enlarging and bulging into the future pericardioperitoneal canals. These two components of the intra-embryonic coelom become the pleural cavities.

A small diverticulum buds off the ventral surface of the foregut to form the lung bud. This grows into the splanchnopleuric mesoderm, enlarging and bulging into the future pericardioperitoneal canals. These two components of the intra-embryonic coelom become the pleural cavities. The lung buds divide rapidly by a process known as branching morphogenesis regulated by a variety of molecular signals. There is, however, an asymmetry in this division such that the left lung has two lobes and the right lung has three.

The lung buds divide rapidly by a process known as branching morphogenesis regulated by a variety of molecular signals. There is, however, an asymmetry in this division such that the left lung has two lobes and the right lung has three. The cartilage and smooth muscle of the airways and visceral pleura develop from the surrounding splanchnopleuric mesoderm. The somatopleuric mesoderm lines the future thoracic wall, as parietal pleura.

The cartilage and smooth muscle of the airways and visceral pleura develop from the surrounding splanchnopleuric mesoderm. The somatopleuric mesoderm lines the future thoracic wall, as parietal pleura. Mature alveoli continue to develop until 6 or 7 years of age. Lung development passes though a number of phases: from an initial glandular stage to a tubular phase, resulting in formation of the airway tubes.

Mature alveoli continue to develop until 6 or 7 years of age. Lung development passes though a number of phases: from an initial glandular stage to a tubular phase, resulting in formation of the airway tubes. After 26 weeks of fetal life the lining of the alveoli thins from a cuboidal to a simple squamous epithelium, thereby facilitating gaseous exchange.

After 26 weeks of fetal life the lining of the alveoli thins from a cuboidal to a simple squamous epithelium, thereby facilitating gaseous exchange. It is not until after this time that air-breathing is possible, and is a reason why premature infants younger than 26 weeks are often non-viable.

It is not until after this time that air-breathing is possible, and is a reason why premature infants younger than 26 weeks are often non-viable. Type I alveolar cells line the walls of the alveoli; type II alveolar cells produce surfactant, a phospholipid material which reduces the surface tension of the fluid in the lungs. This helps prevent collapse of the alveolar spaces. Infants in whom type II alveolar cells do not produce surfactant may suffer from respiratory distress syndrome.

Type I alveolar cells line the walls of the alveoli; type II alveolar cells produce surfactant, a phospholipid material which reduces the surface tension of the fluid in the lungs. This helps prevent collapse of the alveolar spaces. Infants in whom type II alveolar cells do not produce surfactant may suffer from respiratory distress syndrome.

Clinical box

Clinical box