8 The rationale for selecting cancer treatment

Introduction

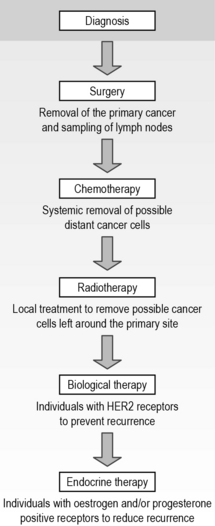

There are a number of treatments used to remove, reduce, halt the growth of a cancer or reduce the symptoms that may result from a cancer. The main treatments explored in the following chapters are identified in Figure 8.1.

Ethical-related factors

All patients have the right to access cancer treatments fairly. However, in the UK, the availability of cancer treatments has not been equal for all patients. Prior to the Calman Hine report (DH 1995) and The NHS Cancer Plan (DH 2000), there was a great deal of regional variation regarding access to cancer treatments, quality of care and healthcare expertise. Each local health authority decided which cancer treatments would be available based on financial budget, immaterial of the effectiveness of drugs or the needs of patients. This resulted in spending variations, known as the ‘postcode lottery’, which may have contributed to higher death rates in some areas (although this was never proven). As a consequence of The NHS Cancer Plan (DH 2000), NICE was set up to review the clinical research trial evidence for each type of cancer and decide which treatments were effective and financially affordable. These two concepts are often in conflict and create ethical debate. Although there has been a reduction in regional inconsistencies and improved national access to research-based and cost-effective treatments, not all treatments are approved by NICE, and those that are approved are still sometimes unavailable and inaccessible by some patients.

Patient-related factors

Patients’ values and beliefs about cancer and treatment may also influence their decisions. These may be based on previous experiences and beliefs. For example, a patient who is a Jehovah’s Witness may refuse a haematological transplant, as this will involve the transfusion of blood products (Holland & Hogg 2001).

Although a patient’s age will not necessarily directly influence the treatment they receive, the older the patient is, the more likely it is that they may have other medical conditions (co-morbidity) such arthritis, diabetes, etc., which may affect the body’s ability to cope with cancer treatment. To measure a patient’s general wellbeing objectively, assessment tools are used such as the Karnofsky scoring system and the World Health Organisation (WHO)/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score (Table 8.1, p.82). This is used to determine whether a patient is fit enough to tolerate treatment.

| Grade | ECOG |

|---|---|

| 0 | Fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction |

| 1 | Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature, e.g. light house work, office work |

| 2 | Ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities Up and about more than 50% of waking hours |

| 3 | Capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours |

| 4 | Completely disabled Cannot carry on any self-care Totally confined to bed or chair |

| 5 | Dead |

http://www.healthtalkonline.org/Cancer/Colorectal_Cancer/Topic/1070/ (accessed November 2011).

Treatment-related factors

As well as financial resources restricting access to cancer treatment, treatment may be restricted by the experience and knowledge of the treatment team, the available clinical research trial results and the complications and potential mortality rates from treatment. A patient’s previous cancer treatment may affect future treatment options. For instance, if an area of the body has already received radiotherapy then it may not be safe to give more. Similarly, some cytotoxic drugs have a maximum lifetime dose limit (Table 8.2).

Table 8.2 Advantages and disadvantages of cancer treatment options

| Treatment | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Gives good indication of the size and extent of cancer No carcinogenic effects May remove all cancer cells if localised |

Patient may not be suitable for a general anaesthetic Possibly life-threatening (bleeding, infection, etc.) May result in change in cosmetic appearance and functioning Does not treat any metastatic spread Long period of recovery |

| Cytotoxics | Systemic – gets rid of metastatic spread Particularly good at destroying rapidly dividing (cancer) cells |

Possible long-term side effects: in fertility, organ function Some cancers are not sensitive to chemotherapy Less effective with bulky, large cancers May cause cancer in later life Time-consuming for patients – repeated appointments May require repeated intravenous access or need for patient to self-medicate oral cytotoxics |

| Radiotherapy | Localised, therefore side effects only occur within the field of treatment Good for palliation of symptoms such as pain, breathlessness |

Possible long-term side effects May not get rid of all cancer cells Some cancers are not radiosensitive May cause cancer in later life Planning is time-consuming Treatment is time-consuming If gonads irradiated, may reduce fertility |

| Biological therapy | Enhances the immune system Narrower range of side effects |

Not suitable for treating all types of cancers Many are still experimental Possible severe allergic reactions May not get rid of all cancer cells |

In order to achieve the best possible outcome, patients often undergo several treatments (multimodality), highlighted in Figure 8.2. In most cases, the idea of this is to remove the primary cancer and treat any potential secondary metastatic spread.

Department of Health. A policy framework for commissioning cancer services: a report by the Expert Advisory Group on Cancer to the Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales. Online. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4071083, 1995. (accessed November 2011)

Department of Health. The NHS cancer plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. Online. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4009609, 2000. (accessed November 2011)

Holland K., Hogg C. Cultural awareness in nursing and health care – an introductory text. London: Arnold; 2001.

Oken M.M., Creech R.H., Tormey D.C., et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American Journal of Clinical Oncology.. 1982;5:649–655.

Corner J., Bailey C. Cancer nursing: care in context, 2nd ed, Oxford: Blackwell, 2008.

Kearney N., Richardson A. Nursing patients with cancer: principles and practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

Munro A. Decision making in cancer care. In: Kearney N., Richardson A. Nursing patients with cancer: principles and practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Souhami R., Tobias J. Cancer and its management, 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2005.

Yarbro C.H., Hansen Frogge M., Godman M. Cancer nursing: principles and practice, 6th ed. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2005.