Chapter 9 The puerperium

CONDUCT OF THE PUERPERIUM

Care of the puerperal woman

Regular checks are made of the temperature and pulse. The perineum is inspected each day to observe the degree of oedema (if any) and the sutures. Many women who have a damaged and repaired perineum experience considerable pain. The woman may need analgesics; perineal pain is discussed further on page 82.

Urinary tract problems

About 10% of puerperal women experience urinary incontinence (usually stress incontinence). In all but a few women this persists for a few weeks and then ceases. Pelvic floor exercises (see p. 311) may speed up the resolution of the problem.

CARE OF THE NEONATE

Checking for congenital abnormalities

A check for major abnormalities is made immediately after the birth and before the baby is given to the mother to celebrate the event. A full check is made during the baby’s first day of life. The procedure is described in Box 9.1.

Box 9.1 Examination of a newborn baby

LACTATION AND BREASTFEEDING

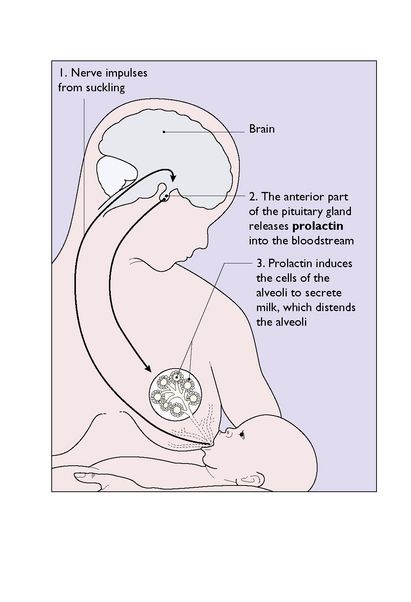

Lactation is encouraged by early and frequent suckling, as this reflexly causes the pituitary gland to secrete hPr (Fig. 9.1). On the other hand, negative emotions, including the fear of failing to breastfeed, may reduce the secretion of prolactin, by promoting the release of the prolactin-inhibiting factor (dopamine) from the hypothalamus. The onset of lactation may be delayed in women who were delivered by caesarean section or following a traumatic labour and birth.

Milk ejection reflex

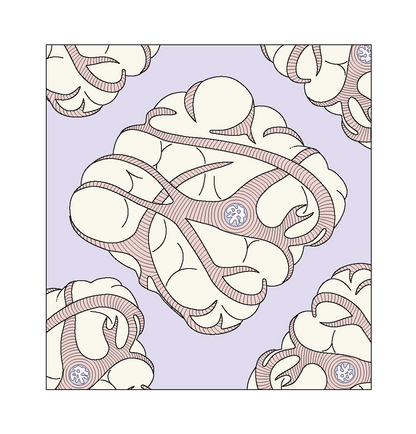

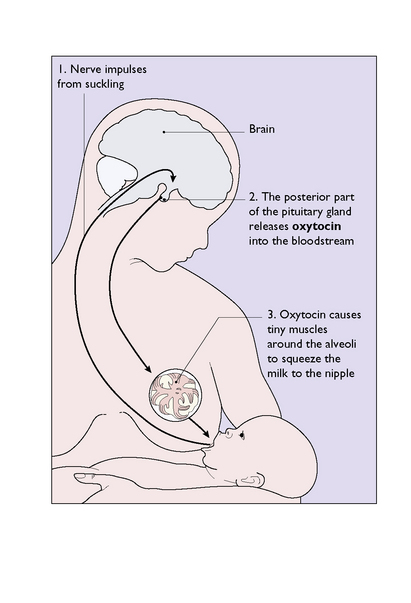

The milk filling and distending the alveoli is unavailable to the infant until myoepithelial cells (Fig. 9.2) that surround the alveoli and smaller ducts contract in response to the milk ejection (or ‘let-down’) reflex. The reflex is initiated by suckling and is mediated via the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, which release oxytocin into the bloodstream (Fig. 9.3).

A joint statement by WHO and UNICEF summarizes the support needed for successful lactation (Box 9.2).

Box 9.2 Ten steps to successful breastfeeding

Every facility providing maternity services and care for newborn infants should:

MAINTENANCE OF LACTATION

Establishment of breastfeeding

The establishment of successful breastfeeding requires:

As mentioned in Box 9.2, breastfeeding is more readily established if:

Technique of breastfeeding

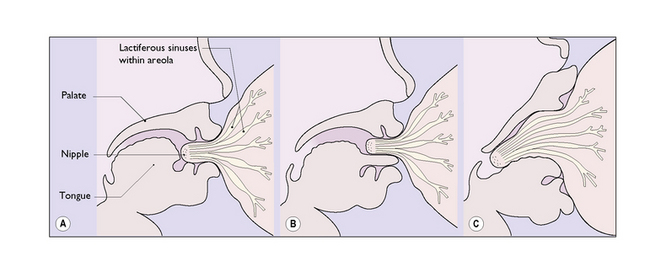

She then holds her breast with the nipple between her forefinger and middle finger, so that the nipple becomes more prominent and the infant is able to put its gums on the areola and not on the tender nipple itself (Fig. 9.4C). This technique enables the baby to breathe when suckling (Figs 9.5 and 9.6).

Breast problems during lactation

Cracked nipples

Aggressive suckling by the baby may lead to cracked nipples, particularly if the nipple is not well within the infant’s mouth (Fig. 9.4A and B). If the cracking is severe, the baby should not be fed from the affected breast, which should be emptied manually or by using a breast pump.

PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN THE PUERPERIUM

A large number of women – probably 50% – experience a heightened state of emotional reactiveness 3–5 days after the birth and about 10% become more severely depressed. Postnatal depression is mentioned here and discussed more fully on page 187.

Adjustment to parenthood and postnatal depression (puerperal depression)

The fatigue induced by the demands of the baby, the emotional readjustment in partner relations, the guilt experienced over failing to cope as well as she expected and lack of a helpful counsellor often induces depression. In mild cases reassurance and advice and providing support for the woman are sufficient. It is also important to tell parents of local community-based help organizations that provide 24-hour home counselling and home visiting when needed. Their activities in helping women adjust to parenthood can be of great value in reducing the incidence of puerperal depression. In 10–20% of women the depression may be more severe and require medication for recovery or to prevent recurrent future depression (see p. 187).

SEXUALITY AFTER CHILDBIRTH

After childbirth the demands of the new baby occupy a good deal of a mother’s time. Moreover, if the mother has had a perineal tear or an episiotomy repaired – in fact if she has needed any stitches – her perineum and vagina may be tender for several weeks or months (see p. 79). It is not unexpected that her desire for sexual intercourse is reduced. Some women who breastfeed may have a reduced libido and develop vaginal dryness, both of which are reversed when they cease breastfeeding. Intercourse is not the only way of obtaining sexual pleasure, and she may welcome touching, cuddling and stimulating her partner if he wishes. When she is ready the couple can resume intercourse. Women may consult a doctor about their lack of sexual feeling after the birth, and supportive advice is helpful.