CHAPTER 1 The psychiatric interview and mental state examination

The key to psychiatric assessment is a comprehensive history and mental state examination. The history needs to cover the history of the presenting complaint, past psychiatric history and a longitudinal perspective of the patient, with important ‘milestones’ and events highlighted. A family history is also important.

Any relevant physical examination and laboratory tests need to be performed to cover treatable ‘organic’ causes and contributors to the psychiatric presentation. This is covered in Chapter 2 of this book.

The framework presented here is taken largely from the so-called ‘Maudsley’ approach, named after the famous London psychiatric hospital. For a more detailed expostulation of the Maudsley approach, see the ‘References and further reading’ at the end of this chapter. This schema is for use in adults: adaptations for children and adolescents, and the elderly, are provided in Chapters 16 and 17, respectively. Special considerations pertinent to people with an intellectual disability are given in Chapter 19.

The history

The main areas covered in the history are shown in Box 1.1. Of course, there is some flexibility about the sequence of questions, but ensure you cover the major areas. Generally, starting with non-directive, ‘open’ questions is recommended, later honing in on specific issues with more focused questioning. Certain issues such as suicidality must always be assessed thoroughly (see Ch 15 for a suggested approach).

Past psychiatric history

Full details are needed of past psychiatric illnesses, including first manifestation of psychiatric symptoms, first contact with a health professional for a mental health problem, and longitudinal course of psychiatric problems, including any hospitalisations; self-harm and suicide attempts should be asked about specifically. An overview is required of treatments received (psychological, medication and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)); engagement with and adherence to such treatments; and treatment response and any adverse effects experienced. A list of current medications should be obtained.

Personal history

The personal history is best mapped in a longitudinal manner.

Pregnancy and birth

Was the pregnancy planned/wanted? Were there any complications during the pregnancy or the birth?

Drug and alcohol history

E Have you found you need an Eye-opener in the mornings after heavy drinking/had to use a drug to settle you down?

E Have you found you need an Eye-opener in the mornings after heavy drinking/had to use a drug to settle you down?Any two positives should prompt a full alcohol/drug history. This should include assessment of the longitudinal course, including first exposure, first regular usage, first problematic usage, periods of abstinence, and periods of heavy use. Treatments, successful and unsuccessful, should be recorded. A typical drinking/drug use day should be mapped, with a view to eliciting elements of the dependence syndrome, such as narrowing of the drinking repertoire, and salience (see also Ch 20). Current use, including quantity and type of substance and route of administration (e.g. intravenous), should be recorded.

The impact of alcohol/drug use on the person’s life should be explored (e.g. impact on relationships, work and studies, physical health and finances). An assessment of the person’s ‘stage of change’ can also be helpful in planning treatment (see Ch 20).

Forensic history

Ask about the person’s forensic history, but in an unthreatening way. For example, ‘Have you ever been in trouble with the law?’ Detail patterns of misdemeanours and consequences, especially convictions and imprisonments.

Premorbid personality

The assessment of personality is difficult, and cross-sectional interviews are suboptimal for this task, especially in the setting of an Axis I disorder (see Ch 12). However, one can get a sense of the person’s inner world, and their way of reacting to others and to the world around them, from the personal history elicited above. At the end of the interview it is instructive to ask: ‘So, what sort of words would you use to describe the “real you”?’ Another approach is: ‘How do you think people who know you well would describe the person you really are?’ A few adjectives can provide a flavour of the person’s view of self.

The mental state examination

The mental state examination aims to provide a comprehensive cross-sectional appraisal of the patient’s current mental state. Current symptoms, and salient symptoms which have been asked about but which are not present, should be reported. The structure shown in Box 1.2 is preferred.

Appearance and behaviour

The idea here is to describe the patient in sufficient detail that a colleague could pick the patient out of a waiting room full of people. Gender, apparent age and ethnicity are all relevant. Clothing should be described, especially if it provides a clinical clue to the working diagnosis, such as flamboyant colours in hypomania, or ill-kempt smelly clothing with numerous layers, in chronic schizophrenia. Florid gaudy make-up can also signal a manic or hypomanic mood state.

Speech

Route taken. The route may be direct from A to B, such as in clear goal-directed speech, or meandering and taking a long and convoluted path but eventually getting to B (circumstantiality, or being circumlocutory). This is seen in anxious people, in obsessionality and in mild schizophrenic thought disorder. In more severely disordered thought, the river runs off at a tangent (tangentiality), or unexpectedly jumps its banks and starts on a completely unconnected route (derailment or knight’s move). In extreme forms, the river gets nowhere at all, meanders around disconnectedly and ends up in a series of eddies (sometimes referred to as word salad).

Route taken. The route may be direct from A to B, such as in clear goal-directed speech, or meandering and taking a long and convoluted path but eventually getting to B (circumstantiality, or being circumlocutory). This is seen in anxious people, in obsessionality and in mild schizophrenic thought disorder. In more severely disordered thought, the river runs off at a tangent (tangentiality), or unexpectedly jumps its banks and starts on a completely unconnected route (derailment or knight’s move). In extreme forms, the river gets nowhere at all, meanders around disconnectedly and ends up in a series of eddies (sometimes referred to as word salad). Amount and speed of flow. The amount of water in the river can be miniscule (paucity of content—seen in both negative symptom schizophrenia and severe depression) and a slow trickle (e.g. short unembellished answers to questions); or a torrent delivered at high speed (pressure of speech—classically, in mania).

Amount and speed of flow. The amount of water in the river can be miniscule (paucity of content—seen in both negative symptom schizophrenia and severe depression) and a slow trickle (e.g. short unembellished answers to questions); or a torrent delivered at high speed (pressure of speech—classically, in mania). Amount of surface variation on the river (prosody) and volume. The water can be still and languid, with no waves (little variation in prosody—monotonous and dull, with a soft voice, as in depression); show the usual lilt of spontaneous speech; or have excessive variation and be too loud, as in mania.

Amount of surface variation on the river (prosody) and volume. The water can be still and languid, with no waves (little variation in prosody—monotonous and dull, with a soft voice, as in depression); show the usual lilt of spontaneous speech; or have excessive variation and be too loud, as in mania.Cognition

It is always required that a brief cognitive screen is performed in patients presenting with psychiatric symptoms, as delirium and dementia can often be missed in their milder forms, and may help explain the rest of the mental state. The use of the full mini-mental state examination (MMSE) (see ‘References and further reading’) has virtue in its being a well-established instrument and a useful screen for dementia, but in some ways individual item scores are more instructive than the total score; nor are all items required in all patients. It is suggested that the items shown in Box 1.3 are a useful brief screen in patients who are not suspected of having a predominant cognitive element to their illness.

BOX 1.3 Brief cognitive screen

A specific area to cover in patients with suspected schizophrenia is that of concreteness of thinking. Ask about similarities and differences (e.g. a wall and a fence) and interpretation of sayings or proverbs (e.g. ‘a rolling stone gathers no moss’); a very literal response suggests concrete thinking (e.g. ‘if a stone rolls down a hill it won’t have any moss growing on it’).

The formulation

Predisposing factors. For example, is there a family history of a mental illness, child sexual abuse, or a difficult relationship with a violent alcoholic father while growing up?

Predisposing factors. For example, is there a family history of a mental illness, child sexual abuse, or a difficult relationship with a violent alcoholic father while growing up? Precipitating factors. For example, has the person experienced death of a loved one, loss of employment, intercession of a physical illness, a traumatic event or an anniversary?

Precipitating factors. For example, has the person experienced death of a loved one, loss of employment, intercession of a physical illness, a traumatic event or an anniversary? Perpetuating factors. For example, is there ongoing alcohol or drug abuse, social isolation, unemployment or financial worries?

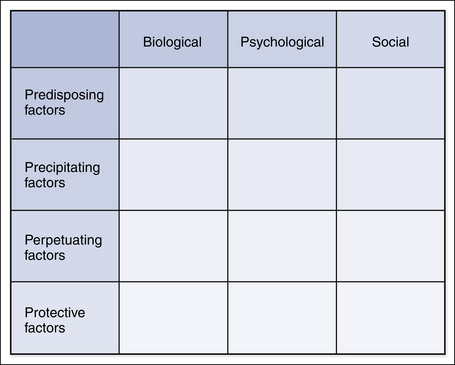

Perpetuating factors. For example, is there ongoing alcohol or drug abuse, social isolation, unemployment or financial worries?It can be helpful to follow the matrix shown in Figure 1.1 to ensure coverage of all aspects of the formulation.

The formulation ends with a working diagnosis and a list of differential diagnoses. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) multiaxial approach can be helpful (see Box 1.4).

BOX 1.4 The DSM multiaxial structure

References and further reading

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. revised

Fish F. Clinical psychopathology. Bristol: Wrights; 1967.

Folstein M., Folstein S., McHugh P. The mini mental state: a practical method for grading of cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189-198.

Goldberg D., Murray R.M. Maudsley handbook of practical psychiatry, 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Mullen P.E. The mental state and states of mind. In: Murray R.M., Kendler K.S., McGuffin P., Wessely S., Castle D.J., editors. Essential psychiatry. 4th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008:1-38.

Sims A. Symptoms in the mind. London: Balliere Tyndall; 1988.