Chapter 12 The psychiatric history and mental state examination

The psychiatric history generally follows the same format as the standard medical history, and the principles described in Chapters 1 and 2 apply just as much here as in any history taking.1 One should inquire about the history of the present illness, the past psychiatric and medical history, and the social and family history. However, the psychiatric history aims to elicit more detail about the patient’s illness from a broad perspective, focusing not only on symptoms but also on the patient’s social background, psychological functioning and life circumstances (a biopsychosocial approach). There is, therefore, more attention paid to the developmental, personal and social history than is normal for a standard medical history.

Obtaining the history

The clinician taking a psychiatric history wants the patient to tell his or her story in his or her own words. In this way the patient will be more likely to report the most important aspects of the illness. This is best achieved using a non-directive approach with open-ended questions. Open-ended questions are those to which the patient will respond with narrative (or a description about what has been happening) rather than a simple factual response. They give the patient an opportunity to talk about his or her problems. Closed questions are more likely to elicit ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. For example, in the assessment of a patient with depression, a closed question would be: ‘Have you been depressed?’ An open-ended question would be: ‘Tell me about how you have been feeling.’ At first glance it might appear that the open-ended question is less efficient, as it could take a longer time to find out about a range of symptoms. However, with a careful and judicious approach, open-ended questioning—by permitting the patient to tell the story—will enable the clinician to get a comprehensive history efficiently. This is not to say that targeted, more-closed questions must not be used—they are necessary to elicit certain symptoms.

History of the presenting illness

In assessing the history of the presenting illness, one needs to cover a number of areas.

1. The problem

A range of symptoms commonly found in psychiatric disorders needs to be reviewed in the course of assessing the history of the present illness. These include mood change, anxiety, worry, sleep pattern, appetite, hallucinations and delusions. A set of simple screening questions for each of the major diagnoses is listed within Table 12.1. It is especially useful to ask about symptoms of anxiety and depression (the most common psychiatric disorders). The definitions of other symptoms are given in Table 12.2. It is important to ask about drug usage (legal and illegal) as well as alcohol and caffeine (which may be associated with anxiety disorders).

TABLE 12.1 The common psychiatric disorders* and their screening questions

| MOOD (AFFECTIVE) DISORDERS | |

| Mood disorders have a pathological disturbance in mood (depression or mania) as the predominant feature. They are distinguished from ‘normal’ mood changes by their persistence, duration and severity, together with the presence of other symptoms and impairment of functioning. | |

| 1. Manic-depressive illness—bipolar disorder | |

| Bipolar disorder is a broad term to describe a recurrent illness characterised by episodes of either mania or depression, with a return to normal functioning between episodes of illness. | |

| a. Mania | |

* Based on the WHO International Classification of Disease 10th ed (ICD-10). ICD-II will be published in 2014.

† Alfons Jakob (1884–1931), professor of neurology in Hamburg from 1924, had over 200 cases of neurosyphilis on his ward at a time; he died of osteomyelitis. Jakob described this cerebral atrophy in 1920 and before Hans Creutzeld (1885–1933).

TABLE 12.2 Symptoms of psychiatric illness

| Affect | The observable behaviour by which a person’s internal emotional state is judged. |

| Agitation (psychomotor agitation) | Excessive motor activity associated with a feeling of inner tension. The activity is usually non-productive and repetitious and consists of such behaviour as pacing, fidgeting, wringing the hands, pulling the clothes and inability to sit still. |

| Anxiety | The apprehensive anticipation of future danger or misfortune. It is associated with feelings of tension and symptoms of autonomic arousal. |

| Conversion symptom (hysteria) | A loss of, or alteration in, motor or sensory function. |

| Psychological factors are judged to be associated with the development of the symptom, which is not fully explained by anatomical or pathological conditions. The symptom is the result of unconscious conflict and is not feigned. | |

| Delusion | A false unshakable idea or belief that is out of keeping with the patient’s educational, cultural and social background. |

| Depersonalisation | An alteration in the awareness of the self—the individual feels as if he or she is unreal. |

| Derealisation | An alteration in the perception or experience of the external world so that it seems unreal. |

| Disorientation | Confusion about the time of day, date or season (time), where one is (place) or who one is (person). |

| Flight of ideas | A nearly continuous flow of accelerated speech with abrupt changes from topic to topic that are usually based on understandable associations, distracting stimuli, or plays on words. When severe, speech may be disorganised or incoherent. |

| Grandiosity | An inflated appraisal of one’s worth, power, knowledge, importance or identity. When extreme, grandiosity may be of delusional proportions. |

| Hallucination | A sensory perception that seems real, but occurs without external stimulation of the relevant sensory organ. The term hallucination is not ordinarily applied to the false perceptions that occur during dreaming, while falling asleep (hypnagogic) or when awakening (hypnopompic). |

| Ideas of reference | The feeling that casual incidents and external events have a particular significance and unusual meaning that is specific to the person. |

| Illusion | A misperception or misinterpretation of a real external stimulus. |

| Mood | A pervasive and sustained emotion that colours the perception of the world. |

| Overvalued idea | An unreasonable belief that is held, but not as strongly as a delusion (i.e. the person is able to acknowledge the possibility that the belief may not be true). The belief is not one that is ordinarily accepted by other members of the person’s culture or subculture. |

| Personality | Enduring patterns of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself. |

| Phobia | A persistent irrational fear of a specific object, activity or situation (the phobic stimulus) that results in a compelling desire to avoid it. |

| Pressured speech | Speech that is increased in amount, accelerated, and difficult or impossible to interrupt. Usually it is also loud and emphatic. Frequently the person talks without any social stimulation and may continue to talk even though no one is listening. |

| Psychomotor retardation | Visible generalised slowing of movements and speech. |

| Psychotic | Psychotic can be used to mean a loss of contact with reality, but is generally used to imply the presence of delusions or hallucinations. |

Based on DSM-IV, APA 1994.2

2. Precipitating events

Psychiatric illness rarely occurs for no reason and there is generally an event that has precipitated the illness. Such events include a range of experiences which may have affected the patient, or a member of the patient’s social network. Events such as physical illness, drug treatment or treatment non-compliance may be implicated as precipitants. The last-mentioned is important, as patients with psychiatric illness are often non-compliant, a major contribution to relapse.

3. Risk

An assessment of the patient’s risk of harm, either to others or to him- or herself, is essential: this will indicate whether the patient needs to be treated involuntarily. Patients with psychotic illness may, in some circumstances, need to be treated involuntarily under the Mental Health Act. While the exact details for involuntary treatment are different under individual mental health acts, the essential features are generally that: (a) a person has a mental illness; and (b) the person is a danger to self or to others. Assessment of danger to others is difficult, with the best predictor being a history of past threat or harm to others. It is best to err on the side of caution in such cases. Assessment of suicide risk needs to be made with sensitivity and using a direct approach, as shown in Table 12.3.

| Suicide may be the unfortunate outcome of psychiatric illness but loss of job, family disruption, alcoholism and self-mutilation can also be the distressing result. Assessing the risk of suicide is an essential part of the psychiatric interview. Asking about this does not increase the risk or put the idea into the patient’s head. It may reduce the risk, as the patient may feel relief in talking about his or her fears. The risk of suicide is assessed by asking directly whether the person has ever contemplated it. |

| Have you thought that life was not worth living? |

| Or |

| Have you felt so bad that you have considered ending it all? |

| If ‘yes’… |

| Have you thought of killing yourself? |

| Have you thought how you might do this? |

| Have you made any plans for doing this? |

The past history and treatment history

Find out what drug treatment has been tried—the class (Table 12.4) of psychiatric medication, its effectiveness and any side-effects. The antipsychotic drugs in particular have common long term side-effects (Table 12.5).

TABLE 12.4 Classes of psychiatric drugs and their major indications

| 1 Anti-anxiety e.g. benzodiazepines, beta-blockers (control somatic symptoms) | For anxiety disorders, insomnia, alcohol withdrawal |

| 2 Antipsychotic e.g. phenothiazine, major tranquillisers | For schizophrenia, mania, delirium |

| 3 Antidepressants e.g. tricyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | For depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| 4 Mood-stabilising e.g. lithium, carbamazepine | For prevention of manic depression or treatment of mania |

TABLE 12.5 Common side effects of the antipsychotic drugs

| 1 Anti-cholinergic—dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, erectile dysfunction |

| 2 Hypersensitivity reactions—photosensitivity dermatitis, cholestatic jaundice, neutrophilia (clozapine) |

| 3 Effects due to dopamine blockade—Parkinsonianism, motor restlessness (akathisia), tardive dyskinesia, dystonia, gynaecomastia, malignant neuroleptic syndrome |

The family history

First, the patient should be asked tactfully if anyone in the family has had any psychiatric or mental illness or has committed suicide. He or she should also be asked if anyone in the family has had any treatment for psychological problems, such as anxiety, depression, agoraphobia,a eating disorders or drug and alcohol problems (these last few areas are often not considered by patients to be psychiatric or mental illnesses).

Childhood abuse (physical or sexual)3 may be an important predisposing event for many illnesses, and should be inquired about. This can be elicited by saying something like ‘Sometimes children can have had some unpleasant experiences—I wonder if you had any? Did anyone ever harm you? … or hit you? … How about interfering with you sexually? … Could you tell me more about that and what happened?’

The mental state examination

While assessing the patient, one should carefully make observations about appearance, behaviour, patterns of speech, attitude to the examiner and ways of interacting. These observations are brought together in a systematic fashion in the mental state examination. This is not something that is ‘done’ at the conclusion of taking a history; it is an essential part of the total process of assessing the patient.4

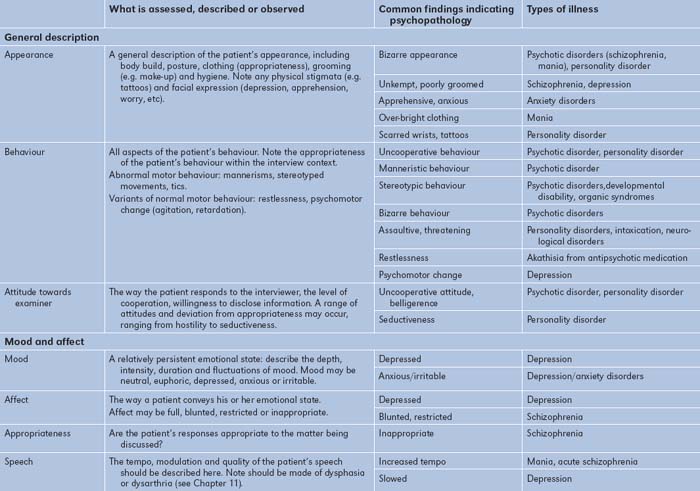

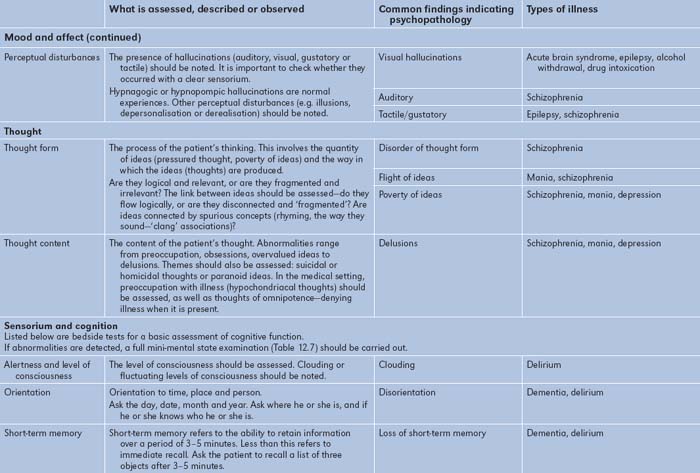

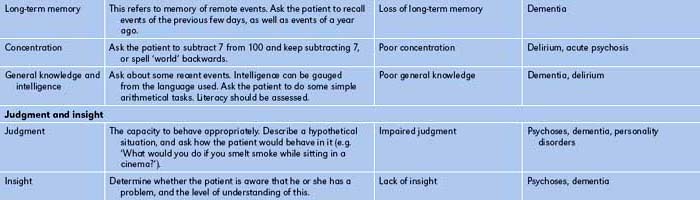

The headings under which the mental state is recorded are shown in Table 12.6, together with some simple bedside tests for assessing cognitive function. Also shown in Table 12.6 are some abnormal features of the mental state examination that are commonly found in psychiatric disorders.

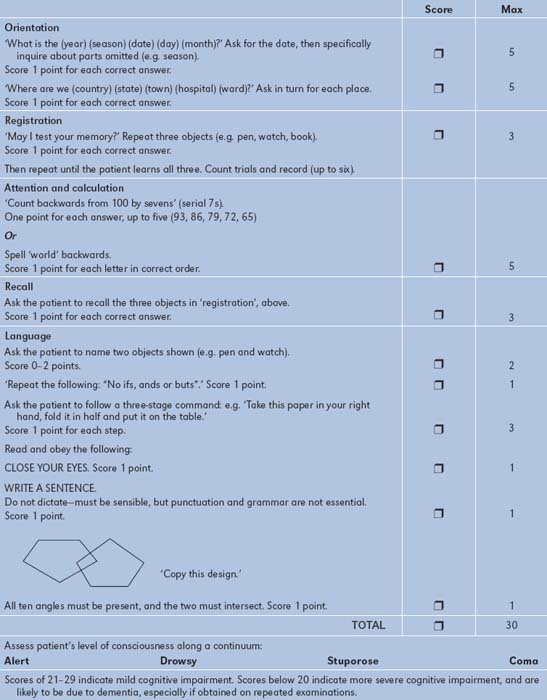

When cognitive dysfunction is suspected, as in patients with dementia,5 a more detailed examination of cognitive function should be carried out. A widely used tool for doing this is the mini-mental state examination,6 which assesses aspects of orientation, memory and concentration. Details of this examination are shown in Table 12.7. Some of the common causes of delirium and dementia are listed in Tables 12.8 and 12.9.

| Drug intoxication | Alcohol |

| Anxiolytics | |

| Digoxin | |

| L-dopa | |

| ‘Street drugs’ | |

| Withdrawal states | Alcohol (delirium tremens) |

| Anxiolytic sedatives | |

| Metabolic disturbance | Uraemia |

| Liver failure | |

| Anoxia | |

| Cardiac failure | |

| Electrolyte imbalance | |

| Postoperative states | |

| Endocrine disturbance | Diabetic ketosis |

| Hypoglycaemia | |

| Systemic infections | Pneumonia |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Septicaemia | |

| Viral infections | |

| Intracranial infection | Encephalitis |

| Meningitis | |

| Other intracranial causes | Space-occupying lesions |

| Raised intracranial pressure | |

| Head injury | Subdural haemorrhage |

| Cerebral contusion | |

| Concussion | |

| Nutritional and vitamin deficiency | Thiamine (Wernicke’ encephalopathy) |

| Vitamin B12 | |

| Nicotinic acid | |

| Epilepsy | Status epilepticus |

| Post-ictal states |

TABLE 12.9 Common causes of dementia

| Degenerative type | Senile dementia of Alzheimer’s |

| Front temporal dementia* | |

| Huntington’s chorea | |

| Parkinson’s disease | |

| Normal-pressure hydrocephalus | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Hereditable Alzheimer’ | Mutation of presenilin-1 |

| Intracranial space-occupying lesions | Tumour |

| Subdural haematomas | |

| Traumatic | Head injuries |

| Boxing encephalopathy | |

| Infections and related conditions | Encephalitis |

| Neurosyphilis | |

| HIV (AIDS dementia) | |

| Jacob-Creutzfeldt disease | |

| Vascular | Multi-infarct dementia |

| Carotid artery occlusion | |

| Metabolic | Uraemia |

| Hepatic failure | |

| Toxic | Alcoholic dementia |

| Heavy-metal poisoning | |

| Anoxia | Anaemia |

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | |

| Cardiac arrest | |

| Chronic respiratory failure | |

| Vitamin deficiency | Vitamin B12 |

| Folic acid | |

| Thiamine (Wernicke–Korsakoff’s syndrome) | |

| Endocrine | Myxoedema |

| Addison’s disease |

The diagnosis

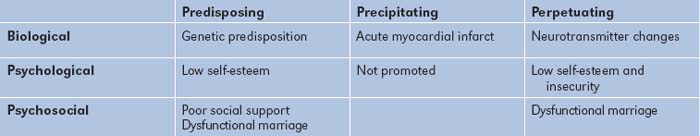

Psychiatric disorders generally arise through a combination of biological, psychological and psychosocial factors, and each of these needs to be considered when a patient’s problem is being assessed (a biopsychosocial approach). The patient’s problem needs to be understood longitudinally, by defining biophysical factors that may have predisposed to the illness and, more immediately, may have precipitated the illness, and factors that may be contributing to the person remaining ill (perpetuating factors). A simple grid can be used for assessing the patient in this manner (Table 12.10). Here biological, psychological or psychosocial factors that predispose to, precipitate or perpetuate the psychiatric illness are identified. Perpetuating factors are very important, particularly among medically ill patients, as it may be the medical or physical illness that maintains the patient’s psychiatric problem. By the same token, psychological factors may perpetuate a patient’s medical illness.

An example of such a formulation grid is shown in Table 12.11 for a 53-year-old man who becomes depressed after a myocardial infarction. He has a family history of depression (a genetic predisposing factor) and chronic low self-esteem (a psychological predisposing factor), which he coped with by succeeding in business. He has few friends and his marriage is unsatisfactory (a psychosocial factor). He had his infarct one week after he heard that he would not be promoted at work (a psychological factor) and his job was at risk (a psychosocial precipitant). His insecurity about work and his failing marriage, together with his low self-esteem, is maintaining his illness, as are the biological changes to the neurotransmitter system.

A good psychiatric history will provide a comprehensive understanding of the patient and will permit appropriate management to be planned. This is immensely rewarding for the clinician, and will also be of considerable benefit to the patient.

1. Kopelman MD. Structured psychiatric interview: psychiatric history and assessment of the mental state. Br J Hosp Med. 1994;52:93-98.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: APA; 1994.

3. Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Lesserman J et al. Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:782–794. A good clinical summary of the relevance of abuse to illness.

4. Davies T. The ABC of mental health. Mental health assessment. BMJ. 1997;314:1536-1539.

5. Johnson J, Sims R, Gottlieb G. Differential diagnosis of dementia, delirium and depression. Implications for drug therapy. Drugs and Aging 1994; 5:431–445. The differential diagnosis hinges on a careful clinical evaluation. Dementia is defined as a chronic loss of intellectual or cognitive function of sufficient severity to interfere with social or occupational function. Delirium is an acute disturbance of consciousness marked by an attention deficit and a change in cognitive ability.

6. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Millennium edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Gleason OC. Delirium. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:1027-1034.

Morgan H, Blashki G. Fits, faints and funny turns. Could it be a mental disorder? Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32:211-213. 216–219

Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, 5th edn. St Louis: Mosby Year Book; 2004.

Zun LS. Evidence-based evaluation of psychiatric patients. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:35-39.