Chapter 20

The Pregnant Patient1

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times … .

Charles Dickens (1812–1870)

General Considerations

As of 2008, the average birth rate for the world was 20.2 live births per year per 1000 total population, which for a world population of 6.6 billion amounts to 134 million babies born per year. In 2010, in the United States, the birth rate was 13 per 1000 total population. The lower birth rate in the United States reflects primarily the current smaller proportion of women of childbearing age as baby boomers age and Americans live longer. The fertility rate was 64.1 births per 1000 women aged 15 to 44 years.

The lowest birth rates worldwide, less than 8.5 per 1000, were recorded in Japan, Germany, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macao. The highest birth rates, 49 or more per 1000, were recorded in Niger, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, and Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In 2010, 3,999,386 births were reported to United States residents, 3% less than in 2009 (4,130,665). The number of births declined for nearly all race and Hispanic origin groups. The general fertility rate was 64.1 births per 1000 U.S. women aged 15 to 44, down 3% from 2009 (66.2). The total fertility rate (estimated number of births in a woman’s lifetime) was 1931 births per 1000 women in 2010, a 4% decline from 2009 (2002).

Childbearing among teenagers has been on a long-term decline in the United States since the late 1950s, except for a brief, but steep, climb in the late 1980s through 1991. The birth rate for United States teenagers aged 15 to 19 fell 10% in 2010, to 34.2 per 1000, reaching the lowest level reported in the United States in seven decades. The number of live births to 15 to 19 year olds was 367,678. Rates declined for teen subgroups aged 10 to 14, 15 to 17, and 18 to 19 and for all race and Hispanic origin groups.

In 2010, the mean age of mother at first birth increased to 25.4 years from 25.2 in 2009. The mean age rose for nearly all race and Hispanic origin groups. The cesarean delivery rate decreased slightly to 32.8% of all births in 2010, the first decline in this rate since 1996. The cesarean rate rose nearly 60% from 1996 to 2009.

Slightly more than 1 per 10 women smoked during pregnancy in 2010, a decline of 44% since these data were first collected in 1989.

Any woman in the reproductive age group who is sexually active and misses her menstrual period should be considered pregnant until proven otherwise. Even if she presents with symptoms not directly related to the abdomen, she should be evaluated for pregnancy. A sexually active woman in the reproductive age group may have a history of amenorrhea (loss of menstrual periods) but can be pregnant nonetheless. Whatever the previous cause of amenorrhea, it may be different now. “Think pregnancy” should be your motto in the evaluation of such patients. This is extremely important because the diagnosis or treatment of a woman’s medical or surgical problem may affect the developing fetus if she is pregnant. As discussed later in this chapter, many of the symptoms of pregnancy are nonspecific and can be interpreted erroneously if the pregnancy is not recognized. For example, the urinary frequency that is common in early pregnancy might easily be mistaken for cystitis. The patient might then receive an antibacterial agent such as a sulfonamide or a quinolone, which is not the best choice for the developing fetus. When the urinary symptoms fail to respond to the medication, the patient might then be referred for intravenous pyelography, which adds the risk of radiation to an early pregnancy.

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

The anatomy and the physiologic changes related to the menstrual cycle that occur in the nonpregnant woman have already been discussed. This chapter reviews the physiologic alterations resulting from pregnancy and the functional pelvic anatomy.

Basic Physiologic Characteristics of Reproduction

When semen is deposited in the vagina, sperm travel through the cervix and uterus and into the fallopian tubes, where fertilization may occur if an ovum is present. The majority of sperm deposited in the vagina die within 1 to 2 hours because of the normal acidic environment. The sperm are aided in their travel into the fallopian tubes by uterine and tubal contractions and favorable mucous conditions.

The fertilized ovum, or zygote, remains in the fallopian tube for approximately 3 days. While in the tube, the fertilized ovum divides repeatedly to form a round mass of cells called the morula. If there is an obstruction in the fallopian tube, the fertilized ovum may become trapped in the tube and attach itself to the lining of the tube, giving rise to an ectopic, or tubal, pregnancy. In a normal pregnancy, approximately 6 to 8 days after fertilization, the morula becomes a blastocyst, which migrates through the tube into the uterus, where it attaches itself to the endometrium (implantation), with the inner cell mass adjacent to the endometrial surface. Substances that destroy the surface epithelial cells are released, allowing the blastocyst to burrow into the endometrium. The endometrium then grows over the invading blastocyst.

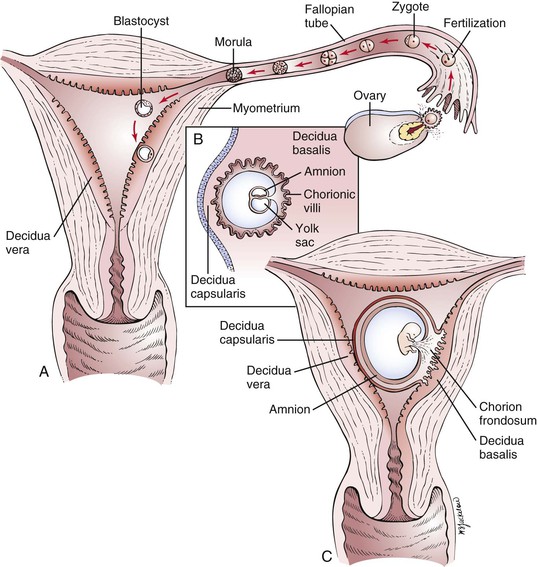

The primitive chorion, the combination of trophoblast and primitive mesoderm, secretes a luteinizing hormone known as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which controls the corpus luteum and inhibits pituitary gonadotropic activity. Quickly thereafter, as the invasion proceeds, maternal venous blood vessels are tapped to form lakes of blood, and chorionic villi develop. These can be identified as early as the twelfth day after fertilization. These villi develop a leafy appearance and are called the chorion frondosum. By the fifteenth day after fertilization, the maternal arterial vessels are tapped, and by the seventeenth to eighteenth day, a functioning placental circulation is established. At term, the uteroplacental blood flow is estimated to be approximately 550 to 705 mL/minute. Figure 20-1A illustrates the path of sperm, fertilization, and implantation.

Figure 20–1 A, Fertilization and implantation. B and C, Cross-sectional view through the uterus of a pregnant woman at approximately 8 days and 20 days, respectively.

Decidua is the name given to the endometrium of pregnancy. There are three types, distinguished by location with regard to the growing embryo. The decidua capsularis is the overlying endothelium that covers the conceptus, and the decidua basalis is the decidual tissue lying between the blastocyst and the myometrium. The decidua of the remainder of the endometrial cavity is the decidua vera. A cross section through the uterus of a pregnant woman and the different types of decidua in early pregnancy are illustrated in Figure 20-1B and C.

One of the first placental hormones produced by the developing trophoblastic tissue is hCG. This hormone is present as early as the eighth day after fertilization has taken place. The titers increase to a maximal level by about the sixtieth to seventieth days after fertilization and then decrease. The primary function of hCG is to maintain the corpus luteum during the first 2 months of pregnancy until the placenta can produce enough progesterone by itself. Other hormones, such as human placental lactogen, human chorionic thyrotropin, and adrenocorticotropic hormone, and estrogens are also produced by the placenta. It is beyond the scope of this book to discuss the actions of these hormones; the reader is referred to the online references for this chapter for further information.

Functional Anatomy of Birth

The pelvic cavity is bounded above by the plane of the brim (the inner sacral promontory to the upper and inner borders of the symphysis pubis), below by the plane of the outlet (the lower and inner borders of the symphysis pubis to the end of the sacrum or coccyx), posteriorly by the sacrum, laterally by the sacrosciatic ligaments and ischial bones, and anteriorly by the pubic rami.

The birth canal, through which the infant is delivered, may be thought of as a cylindric passage with walls composed partially of hard parts (the bony pelvis) and partially of soft parts (the muscles of the pelvic floor and the pelvic ligaments). The cross section of the cylinder is oval, rather than circular, to accommodate the oval cross section of the entering fetal part (e.g., the head) as it descends through the pelvis as a result of the expulsive effect of uterine contractions.

This mechanism for delivery and its corresponding anatomy would be easily understood were it not for the fact that the long axis of the schematic oval, which lies transversely at the entrance to the pelvis, comes to lie in the anteroposterior axis in the midpelvis. The entering fetal part must therefore descend in a spiral path as it progresses through the birth canal.

The process of birth varies greatly, depending on the relationships—lie, presentation, attitude, and position—of the fetus to the maternal anatomy. It is important to define these relationships accurately to understand the birth process.

The term lie refers to the relation of the long axis of the fetus to that of the mother. In more than 99% of full-term pregnancies, the lie is in the same plane as or parallel to the long axis of the mother; this is called a longitudinal lie. In rare instances, the long axis of the fetus is perpendicular to the maternal pelvis; this is called a transverse lie.

The term presentation refers to the part of the fetus in the lower pole of the uterus overlying the pelvic brim (e.g., cephalic, vertex, breech) that can be felt through the cervix. Usually the fetus’s head is flexed so that the chin is in contact with the chest. In this case, the occipital fontanelle is the presenting part, and the presentation is referred to as a vertex presentation. The fetus is in the occiput or vertex presentation in approximately 95% of all labors.

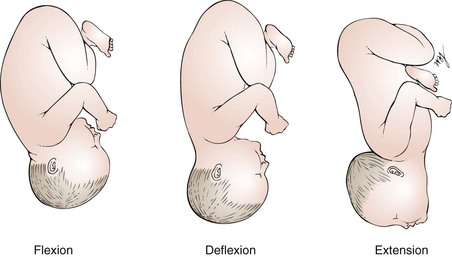

The attitude, or habitus, of the fetus is the posture of the fetus: flexion, deflexion, or extension. Figure 20-2 illustrates these postures. In most cases, the fetus becomes bent over so that the back is convex, the head is sharply flexed on the chest, the thighs are flexed over the abdomen, and the legs are bent at the knees. This is the description of the fetal attitude of flexion.

Figure 20–2 Types of fetal positions.

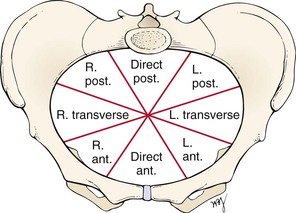

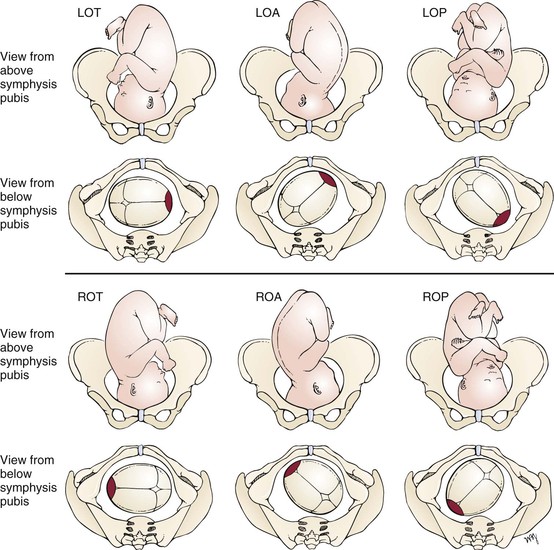

The position is the relationship of an arbitrarily chosen portion of the presenting part of the fetus to the maternal pelvis. For example, in a vertex presentation, the chosen portion is the fetal occiput; in a breech presentation, it is the sacrum; and in a face presentation, it is the chin, termed the mentum. The maternal pelvis is divided into eight parts for the purpose of further defining position. These divisions are shown in Figure 20-3.

Figure 20–3 Divisions of maternal pelvis as seen from above. ant., Anterior; L., left; post., posterior; R., right.

Because the arbitrarily chosen portion of the presenting part may be either left or right, the portion can be described as left occiput (LO), right occiput (RO), left sacral (LS), right sacral (RS), left mental (LM), or right mental (RM). This part is also directed anteriorly (A), posteriorly (P), or transversely (T). For each of the three presentations (vertex, breech, and face), there are therefore six varieties of position. For example, in a vertex presentation, if the occiput is in the left anterior segment of the maternal pelvis, the position is described as left occiput anterior (LOA), which is the most common of all vertex presentations. The common clinical vertex positions are illustrated in Figure 20-4. Left and right always denote the side of the mother. Likewise, anterior, posterior, and transverse refer to the mother’s pelvis.

Figure 20–4 Common clinical vertex positions. For each position shown, the top diagram is the view from above the symphysis pubis; the bottom is the view from below the symphysis pubis. Right and left refer to the mother’s side. Anterior, posterior, and transverse refer to the maternal pelvis. Red area is the fetal occiput. LOA, Left occiput anterior; LOP, left occiput posterior; LOT, left occiput transverse; ROA, right occiput anterior; ROP, right occiput posterior; ROT, right occiput transverse.

The term station characterizes the level of descent of the presenting part of the fetus; “0 station” signifies that the fetal occiput has reached the level of the maternal ischial spines and that the widest transverse part of the infant’s head (biparietal diameter) is at the level of the pelvic brim. This is also known as engagement. If the vertex is at “−1 station,” it means that the fetal occiput is at a plane 1 cm above the level of the maternal ischial spines (and that the biparietal diameter is therefore 1 cm above the pelvic brim), and the infant’s head is therefore not engaged.

The cardinal movements of labor are engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and expulsion.

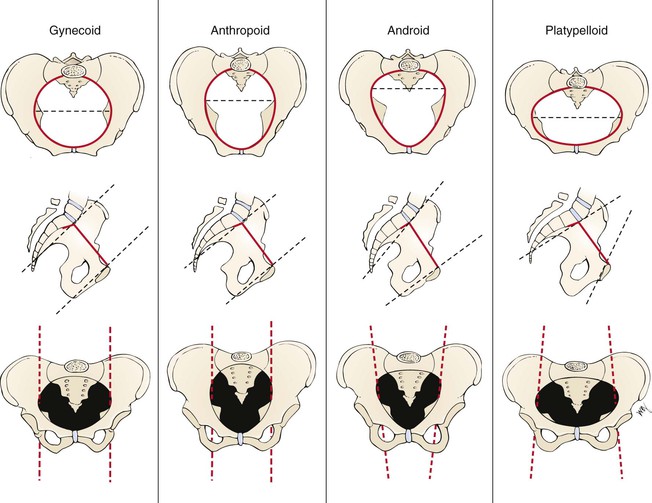

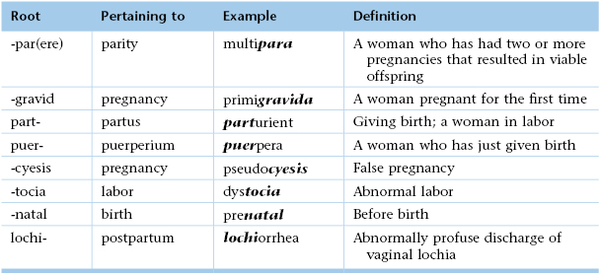

There are four basic pelvic configurations: gynecoid, anthropoid, android, and platypelloid. These are based on the shape of the brim, midpelvis, and outlet. Any pelvis is likely to combine features of more than one configuration. Figure 20-5 illustrates these basic types and summarizes the differences in pelvic anatomy.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most common symptoms of pregnancy are the following:

Amenorrhea

Amenorrhea results from the high levels of estrogen, progesterone, and hCG, which increase and alter (decidualize) the uterine endometrium and do not allow the endometrium to slough as in menstrual bleeding.

Nausea

Nausea, with or without vomiting, is the so-called morning sickness of pregnancy. As the name implies, the symptom is usually worse during the early part of the day and usually passes in a few hours, although it may last longer. More than 50% of all pregnant women in their first trimester have gastrointestinal symptoms. Although the cause is unknown, high levels of estrogen and hCG have been implicated in its development. Pregnant women are also hypersensitive to odors, and they may experience alterations in taste. Morning sickness usually improves after 12 to 16 weeks, when the hCG levels fall. Severe vomiting may occur, resulting in dehydration and ketosis, but this is uncommon, occurring in fewer than 2% of pregnancies.

Breast Changes

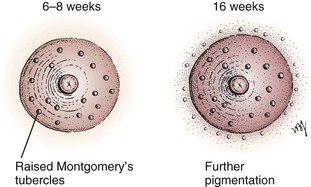

Several changes in the breast occur with pregnancy. One of the earliest symptoms is an increase in the vascularity of the breast, associated with a sensation of heaviness, almost pain. This occurs at approximately the sixth week. By the eighth week, the nipple and areola have become more pigmented, and the nipple becomes more erectile. The Montgomery tubercles become prominent as raised pinkish-red nodules on the areola. By the sixteenth week, a clear fluid called colostrum is secreted and may be expressed from the nipple. By the twentieth week, further pigmentation and mottling of the areola have developed. Figure 20-6 illustrates the changes in the nipple and areola.

Figure 20–6 Nipple and areola changes during pregnancy.

Heartburn

Heartburn in pregnancy occurs because progesterone causes relaxation of the gastroesophageal sphincter. Another cause of heartburn in the third trimester is the pushing upward of the enlarged uterus. This upward displacement exerts pressure on the stomach. There is a decrease in gastric motility, as well as a decrease in gastric acid secretion, which delays digestion.

Backache

As a result of secretion of estrogen and progesterone, the pelvic joints relax, and the increased uterine weight accentuates lordosis. The abdominal muscles stretch and lose tone.

Abdominal Enlargement

The uterus rises out of the pelvis and into the abdomen by the twelfth week of gestation, and an increase in abdominal girth is usually apparent by the fifteenth week. This enlargement is usually more apparent earlier in multiparous women, whose abdominal muscles have lost some of their tone during previous pregnancies.

Quickening

Quickening is the sensation of fetal movement. It is a faint sensation initially. Quickening usually begins at 20 weeks in the primigravida but is usually felt 2 to 3 weeks earlier in the multipara.

Skin Changes

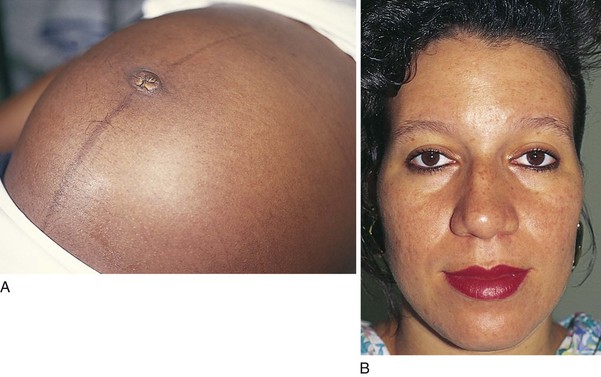

In addition to the skin changes of the breast already discussed, hyperpigmentation is common, especially in women with dark hair and a dark complexion. The linea alba darkens to become the linea nigra, as shown in Figure 20-7A. Areas prone to friction (e.g., medial thighs, axilla) also tend to darken. New pigmentation on the face, called chloasma, also commonly develops on the cheeks, forehead, nose, and chin. These skin changes are caused by the presence of high levels of ovarian, placental, and pituitary hormones. A woman with chloasma appears in Figure 20-7B.

Figure 20–7 Skin changes resulting from high levels of ovarian, placental, and pituitary hormones. A, Linea nigra. B, Chloasma.

“Stretch marks,” or striae gravidarum, are irregular, linear, pinkish-purple lesions that develop on the abdomen, breasts, upper arms, buttocks, and thighs. They are caused by tears in the connective tissue below the stratum corneum. Figures 20-8 and 20-9 show striae gravidarum of the abdomen and breasts, respectively. The linea nigra is also present on the patient in Figure 20-8. Figure 20-10 illustrates the common skin changes seen in pregnancy.

Figure 20–10 Common skin changes during pregnancy.

Transverse grooving, as well as increased brittleness or softening, of the nails may occur. Eccrine sweating progressively increases throughout pregnancy, whereas apocrine gland activity decreases. Hirsutism, caused by increased androgen secretion, may also occur on the face, arms, legs, and back.

Changes in Urination

Beginning at the sixth week, urinary bladder symptoms are common. Increased frequency of urination is thought to be caused by increased vascularity of the bladder, as well as by pressure of the enlarging uterus on the bladder. As the uterus rises above the pelvis, the symptoms tend to remit. Near term, however, urinary symptoms recur as the fetal head settles into the maternal pelvis and impinges on the volume capacity of the urinary bladder.

Vaginal Discharge

An asymptomatic, white, milky vaginal discharge is common as the elevated estrogen levels increase the production of cervical mucus and secretions from the vaginal walls.

Fatigue

Easy fatigability is common during early pregnancy. Some women feel that progesterone makes them feel drowsy and contributes to fatigue.

Other Symptoms

Several other symptoms are common in pregnant women. These include varicose veins, headache, leg cramps, swelling of the legs and hands, constipation, bleeding gums, nosebleeds, insomnia, and “dizziness.”

Obstetric Risk Assessment

Documentation of the medical history of the pregnant woman is similar to that of the nonpregnant woman. In addition, the interviewer must assess obstetric risk. The following major risk factors must be evaluated:

• Age

• Parity

• Height

• Diabetes, hypertension, and renal disease

• Hemoglobinopathy and isoimmunization

• History of previous pregnancies

Age

As maternal age increases, the risk of conceiving a fetus with a chromosomal abnormality increases. The chance of having a child with a chromosomal abnormality is approximately 1 per 200 at age 35 years and increases to approximately 1 per 20 at age 44 years. Women younger than 20 years are at increased risk of having a preterm birth or low-birth-weight baby, when compared with women aged 25 to 35 years.

Parity

Women who have had more than five children are at increased risk of placenta previa and placenta accreta, possibly because of scarring of the endometrium. Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) and uterine rupture are also more common in this group of women.

Height

Women who are less than 5 feet (152.5 cm) tall may have small pelves and may be prone to cephalopelvic disproportion,2 requiring cesarean section.

Pregnancy Weight

Perinatal mortality rate is increased among women whose initial prepregnancy weight is less than 120 pounds, especially if their weight gain during pregnancy is less than 11 pounds. Being overweight or obese also puts the mother and her fetus at increased risk of obstetric complications, including early miscarriage, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, fetal macrosomia, cesarean delivery, and operative complications such as increased operative time, increased blood loss, infection, and anesthetic complications. Therefore women who are significantly underweight or overweight should undergo medical and nutritional evaluation, as well as support and counseling to attain a healthy weight before becoming pregnant.

Diabetes, Hypertension, or Renal Disease

In women with diabetes, hypertension, or renal disease, there is an increased risk of fetal intrauterine growth restriction, preterm labor, preeclampsia, and abruptio placentae. Diabetes mellitus occurs in 2% to 3% of all pregnancies and is thus the most common medical complication of pregnancy. Screening for gestational diabetes is routine during pregnancy because the rate of gestational diabetes may be as high as 30% of births.

Hemoglobinopathy and Isoimmunization

Determine the presence of any hemoglobinopathy because pregnancy can precipitate an exacerbation of the anemia. Women who are Rh-negative must be monitored closely throughout pregnancy if they have Rh antibodies from isoimmunization because severe hemolytic anemia may develop in the fetus before delivery.

History of Previous Pregnancies

A history of traumatic or second trimester fetal loss increases the possibility of cervical injury and subsequent cervical incompetence. A history of preterm delivery (<37 weeks gestation) increases the probability of recurrent early delivery. These patients require particularly close surveillance. A history of unexplained pregnancy loss in the third trimester should alert the clinician to undiagnosed medical problems in the mother, such as gestational diabetes or systemic lupus erythematosus. For women who have undergone previous cesarean section, there must be exact information about the reason for the procedure and the type of uterine incision used, so that it can be determined whether the patient is a candidate for a vaginal birth.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Because medical therapy for a mother who is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive can reduce transmission of the infection to the fetus by more than two thirds, it is obvious that identification of HIV-positive mothers is essential. Although HIV testing cannot be required of the mother, it is mandatory that she be counseled about the value of testing. Screening for HIV is routinely offered and is usually (90%) accepted. A history of genital herpes simplex necessitates screening for recurrences near the time of delivery because cesarean delivery may be necessary to prevent transmission to the neonate. Screening for gonorrhea is performed in high-risk populations.

Other Infections

Assessment regarding exposure to rubella, chickenpox, and parvovirus (Fifth disease) is critical. It may be necessary to determine antibody titers. Screening for syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, hepatitis B surface antigen, and group B streptococcus in the third trimester is routine. Screening for tuberculosis is performed in high-risk populations.

Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drug Use

Determinations must be made regarding tobacco, alcohol, and drug use; exposure to toxic substances in the workplace or at home; and exposure to other teratogenic agents. Women who smoke cigarettes place their fetuses at a higher risk of complications and should be encouraged to stop smoking. The fetus is more likely to exhibit intrauterine growth restriction and to become hypoxic during labor as a result of a reduction in placental exchange. Special note must be made of any drugs taken during pregnancy. Ideally, this issue should be discussed before the woman conceives so that she can be taking the safest possible medication for pregnancy.

Eliminating these risk factors is recommended to improve perinatal outcomes.

Calculation of Due Date

A question that most women have after being told that they are pregnant is “When am I due?” To calculate the expected date of confinement (EDC), first determine the date of the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) and then calculate the EDC as follows:

| LMP | 3/29/2013 |

| Go back 3 months | 12/29/2012 |

| Add 1 year | 12/29/2013 |

| Add 7 days | 1/05/2014 = EDC |

EDC, Expected date of confinement; LMP, last menstrual period.

Alternatively, the EDC can be calculated by adding 9 months and 7 days to the first day of the LMP. This calculation is based on a gestation of 280 days and is known as Nägele‘s rule. By knowing the EDC, the examiner can predict the size of the uterus on physical examination, provided that the LMP is correct and that conception actually occurred at that time. If the size of the uterus differs significantly from that expected according to the EDC, the causes must be determined. Early ultrasonography can be helpful in dating a pregnancy.

Effect of Pregnancy on the Patient

Pregnancy can be one of the most exciting times in a woman’s life but it can also present some challenges. Even a woman who experiences joy from becoming pregnant may experience stress and anxiety during her pregnancy. “Will the baby be healthy?” “How will I tolerate labor?” “How will the baby change my life?” “I’ve put on so much weight. Will I ever be able to take it off?” These are just a few of the many questions commonly asked by pregnant women.

Pregnancy may worsen an existing psychiatric condition. It has been estimated that one per five pregnant women experiences some sort of mental health problem during pregnancy. In addition, a severe psychotic episode occurs in 1 to 2 women per 1000 live births.

Depression is common during pregnancy; almost 15% of all pregnant women experience some degree of depression during pregnancy, and 8% experience depression during the postpartum period. Postpartum blues may be related to the diminishing of excitement after delivery, the loss of sleep during labor, anxiety about the ability to care for the child, perineal pain, feeding difficulties, and concern about appearance. Fortunately, the blues are usually self-limited and remit within a few weeks. Women who experience persistent symptoms of depression in the postpartum period should seek medical evaluation because psychotherapy and medications are effective in treating postpartum depression.

Physical Examination

The equipment necessary for the examination of the pregnant woman is the same as for the nonpregnant woman. In addition, specialized instruments such as an ultrasonic Doppler scanner or fetoscope may be used to listen to the fetal heart. The ultrasonic scanner can detect the fetal heartbeat as early as gestational weeks 6 to 7; an ultrasonic Doppler scanner is used at about week 10; and a fetoscope or stethoscope can be used after the twentieth week to auscultate the fetal heartbeat.

Always try to make the patient as comfortable as possible. She should be examined in comfortable surroundings, with attention to privacy. Discuss with her all the procedures that you will perform. The patient’s gown should open in the front for ease of examination. The patient is draped in the same way as discussed in previous chapters and as shown in Figure 16-26. If the patient is in advanced pregnancy, avoid having her lie for a long period on her back, because the gravid uterus diminishes venous return and produces supine hypotension. It is useful for the woman to urinate before the pelvic examination. As always, wash your hands before beginning the examination. Make sure that your hands are warm and dry.

Because the examination of the pregnant woman is identical to the examinations described in the other chapters of this book, only special techniques and modifications for pregnancy are discussed here.

Initial Comprehensive Evaluation

There are three main goals to the initial evaluation:

The physical examination must include the following:

• Determination of height and weight

• Assessment of blood pressure

• Inspection of the teeth and gums

• Palpation of the thyroid gland

• Auscultation of the heart and lungs

• Examination of the breasts and nipples

• Examination of the legs for varicosities and edema

• Inspection of the vulva, vagina, and cervix

• Cytologic study (Pap smear) and testing for human papillomavirus (HPV)

Whenever possible, ultrasonography should be performed at the first prenatal visit to verify the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy with a fetal heartbeat, to confirm or adjust the gestational age, and to check for multiple fetuses. Another sonographic examination is usually performed at about 16 to 20 weeks to evaluate the fetal anatomy and identify any structural anomalies.

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat, and Neck

Inspect the face. Is chloasma present? What is the texture of the hair and skin? Inspect the mouth. What is the condition of the teeth and gums? Palpate the thyroid. Is it enlarged symmetrically?

Chest

Inspect, palpate, and auscultate the chest. Is there any evidence of labored breathing?

Heart

Palpate for the point of maximum impulse. Is it displaced laterally? During the later stages of pregnancy, the gravid uterus pushes up on the diaphragm, and the point of maximum impulse is displaced laterally. Auscultate the heart. Systolic ejection murmurs are common during pregnancy as a result of the hyperdynamic state. Diastolic murmurs are always indicative of a pathologic condition.

Breasts

Inspect the breasts. Are they symmetric? Notice the presence of vascular engorgement and pigmentary changes. Are the nipples everted? An inverted nipple may interfere with a woman’s plans to breast-feed. Palpate the breasts. The normal nodularity of breast tissue is accentuated during pregnancy, but any discrete mass should be considered indicative of a pathologic condition until proven otherwise and should be evaluated.

Abdomen

Inspect for the linea nigra and striae gravidarum. Notice the contour of the abdomen. Palpate the abdomen. Fetal movement may be felt by the examiner after 24 weeks. Are there uterine contractions? Hold your hand on the abdomen as the uterus relaxes.

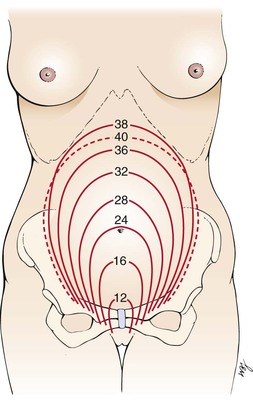

Use a tape measure to assess the fundal height. The measurement should be taken from the top of the symphysis pubis in a straight line to the top of the fundus, with the bladder empty. The technique is demonstrated in Figure 20-11. Between 20 and 32 weeks, the superior-inferior measurement in centimeters should equal the number of weeks of gestation. The uterus rises up and enters the abdomen at 12 weeks. It reaches the umbilicus at approximately 20 weeks and is just under the costal margin by 36 weeks. The reduction in fundal height that usually occurs between the thirty-eighth and fortieth weeks is called lightening and results from the descent of the fetus into the pelvis, or “dropping.” Figure 20-12 illustrates the approximate size of the uterus by weeks.

Figure 20–11 Technique for measuring fundal height.

Figure 20–12 Approximate uterine size by week.

Auscultate the fetal heart and determine the fetal heart rate (FHR), and note its location. Throughout pregnancy, the FHR is approximately 120 to 160 beats per minute. From weeks 12 to 18, the FHR is usually detected in the midline of the mother’s lower abdomen. After 30 weeks, the FHR is best heard over the fetal chest or back. Knowing the location of the fetal back is helpful in determining where to listen for the FHR.

Genitalia

Inspect the mother’s external genitalia. Are any lesions present? Inspect the anus. Are varicosities present?

With gloves on, perform a speculum examination as described in Chapter 16, Female Genitalia. Inspect the cervix. A dusky blue color is characteristic of pregnancy and occurs by weeks 6 to 8. Is the cervix dilated? If so, fetal membranes may be seen within. Note the character of the vaginal secretions. Obtain cytologic studies for a Pap test and HPV and a swab for Chlamydia organisms and gonorrhea. As the speculum is removed, inspect the vaginal walls. The vaginal walls are commonly violaceous in pregnancy. Withdraw the speculum carefully.

Perform a digital bimanual examination, paying special attention to the consistency, length, and dilation of the cervix; the fetal presenting part (in advanced pregnancy); the structure of the pelvis; and any abnormalities of the vagina and perineum. Is the cervix closed? A nulliparous cervix should be closed, whereas a multiparous cervix may allow the tip of a finger through the external os. Estimate the length of the cervix by palpating the lateral side of the cervix from the cervical tip to the lateral fornix. Only at term should the cervix shorten, or efface. The normal length of the palpable (vaginal) portion of the cervix is 1.5 to 2 cm.

Palpate the uterus for size, consistency, and position. An early sign of pregnancy, at approximately 6 to 12 weeks, is the softening of the entire isthmus of the cervix; this is known as Hegar‘s sign. During the bimanual examination of the uterus, the examiner will notice an extreme softening of the lower uterine segment. This produces a sensation of the close proximity of the fingers of the hand in the vagina (internal) and that in the abdomen (external). The technique for evaluating the presence of Hegar’s sign is illustrated in Figure 20-13. Bimanual palpation of the uterus is useful up to about 12 to 14 weeks’ pregnancy. After that, the uterus can be palpated abdominally. Fetal parts are usually palpated from about 26 to 28 weeks’ gestation by abdominal examination (described later).

Palpate the adnexa. Early in pregnancy, the corpus luteum may be palpable as a cystic mass on one ovary. As you withdraw your hand from the vagina, evaluate the pelvic muscles.

Extremities

Inspect for varicosities. Is edema present?

This completes the routine initial examination.

Subsequent Antenatal Examinations

Subsequent antenatal examinations are important for screening for impaired fetal growth, malpresentation, anemia, preeclampsia, and other problems. In the absence of specific complaints by the patient or of abnormal findings on the initial examination or initial laboratory and sonographic studies, only a few parts of the physical examination just outlined are routinely performed during each visit. These include weight, blood pressure, and examination of the abdomen. This section concerns the abdominal examination.

The physical examination should confirm that fetal growth is consistent with gestational age. Attention should then be given to assessing the lie and presentation of the fetus. From the twenty-eighth week of gestation to term, the following four maneuvers, known as Leopold‘s maneuvers, provide vital information for the examiner about these important questions. The patient lies supine for these maneuvers.

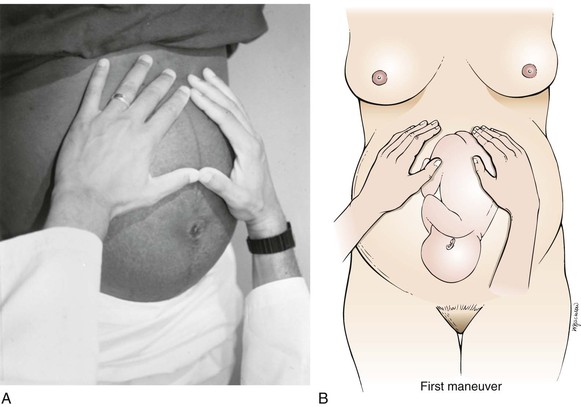

The first maneuver is used to evaluate the upper pole and defines the fetal part in the fundus of the uterus. Stand facing the patient at her side, and gently palpate the upper uterine fundus with your fingers to ascertain which fetal pole is present. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 20-14. Usually, the fetal buttocks are felt at the upper pole. They feel firm but irregular. In a breech presentation, the head is at the upper pole. The head feels hard and round and is usually movable.

Figure 20–14 Leopold’s first maneuver. A, Position of clinician’s hands on mother’s abdomen. B, Illustration of relationship of clinician’s hands and fetus.

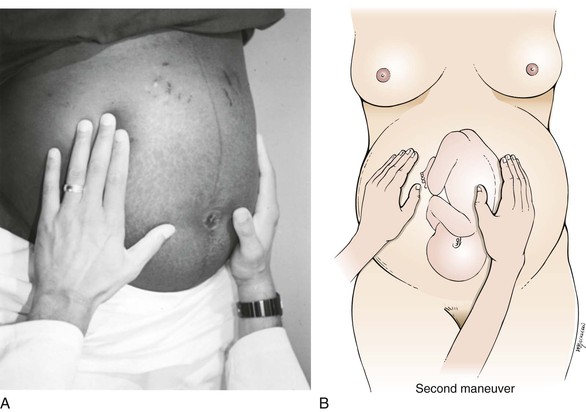

The second maneuver is used to locate the position of the fetal back. Standing in the same place as in the first maneuver, place the palms of your hands on either side of her abdomen, and apply gentle pressure to the uterus to identify the fetal back and limbs, as shown in Figure 20-15. On one side, the fetal back is felt: rounded, smooth, and hard. On the other side are the limbs, which are nodular or bumpy, and kicking may be felt.

Figure 20–15 Leopold’s second maneuver. A, Position of clinician’s hands on mother’s abdomen. B, Illustration of relationship of clinician’s hands and fetus.

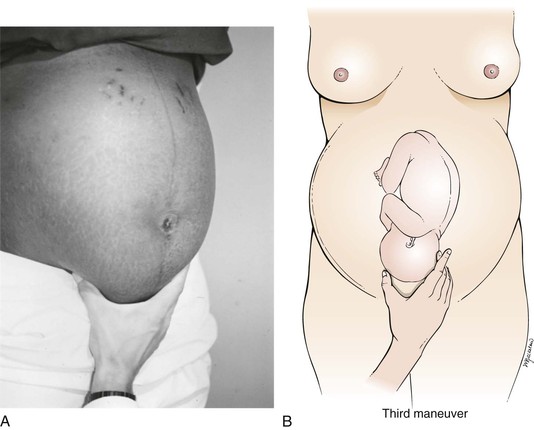

The third maneuver is to palpate the lower pole of the fetus. From the same position as in the first two maneuvers, use your thumb and fingers of one hand to grasp the lower portion of the maternal abdomen just above the symphysis pubis. This maneuver is illustrated in Figure 20-16. If the presenting portion is not engaged, a movable part, usually the head of the fetus, is felt. If the presenting portion is engaged, this maneuver indicates that the lower pole of the fetus is fixed in the pelvis.

Figure 20–16 Leopold’s third maneuver. Relationship of clinician’s hand and fetal presenting part. A, Position of clinician’s hand on mother’s abdomen. B, Illustration of relationship of clinician’s hand and fetus.

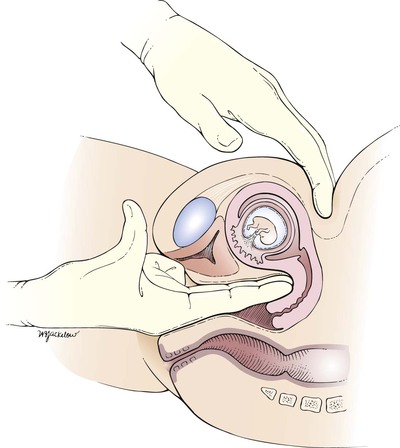

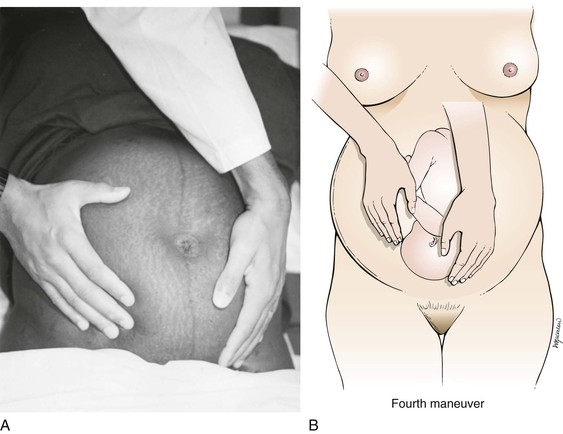

The fourth maneuver is performed to confirm the presenting portion and to locate the side of the fetus’s cephalic prominence. You should now stand beside the patient, facing her feet. Place your hands on either side of her lower abdomen. With the tips of your fingers, exert a deep pressure in the direction of the pelvic inlet, as indicated in Figure 20-17. If the presenting portion is the head and the head is flexed normally, one hand will be stopped by the cephalic prominence as the other hand descends farther down on the pelvis. In a vertex presentation, the cephalic prominence is on the same side as the fetal small parts. In a vertex presentation with the head extended, the prominence is on the side of the back.

Figure 20–17 Leopold’s fourth maneuver. Relationship of clinician’s hands and fetal presenting part. A, Position of clinician’s hands on mother’s abdomen. B, Illustration of relationship of clinician’s hands and fetus. Note that the examiner’s right hand is stopped higher by the fetus’s cephalic prominence.

Labor is the process of birth. The diagnosis and the mechanism of labor are complex topics and are beyond the scope of this book. The reader is referred to the online references for this chapter for discussions of these topics.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Bleeding during pregnancy is fairly common but is not considered to be normal. The causes may be benign or serious and vary according to the stage of pregnancy and the nature of the bleeding.

First trimester bleeding may be indicative of implantation of the ovum, or it may be indicative of cervicitis or vaginal varicosities. More seriously, it could be indicative of a threatened, inevitable, incomplete, or complete abortion.

A threatened abortion should always be considered when vaginal bleeding occurs in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy.

An inevitable abortion can be diagnosed if a patient presents during the first half of pregnancy with bleeding and crampy abdominal pain in association with a dilated cervix or a gush of fluid (rupture of membranes) without passing of the products of conception.

An incomplete or complete abortion occurs when part or all of the products of conception are extruded through the cervix and into the vagina and are passed out of the body.

Second or third trimester bleeding occurs in approximately 3% of all pregnancies. Approximately 60% of these bleeding episodes result from placenta previa or abruptio placentae. Both of these conditions may gravely endanger the mother and fetus.

The incidence of placenta previa is approximately 1 per 250 deliveries and is more common among multiparas than among primigravidas. Placenta previa is characterized by painless vaginal bleeding in association with a soft, nontender uterus. The hemorrhage usually does not occur until the end of the second trimester or later. Although there are several types of placenta previa, the symptoms arise from the abnormal location of the placenta over or near the internal os of the cervix. Ninety percent of all patients with placenta previa have at least one antepartum hemorrhage. There is also a 20% incidence of preterm delivery because of hemorrhage.

Abruptio placentae is the premature separation of a normally situated placenta. It also has an incidence of 1 per 75 to 225 deliveries. The symptoms include mild to severe pain with or without external bleeding in association with increasing uterine tone and tenderness. Fetal distress may or may not occur. The incidence of abruptio placentae is higher among women with high parity. It is also more common among African-American women than among white or Latino women. Hypertension is, by far, the most commonly associated condition. Cigarette smoking and cocaine abuse have also been linked to an increased risk of abruptio placentae. Women with a history of abruptio placentae are at significant risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies.

Vasa praevia is another serious but rare condition in which some of the fetal vessels in the membranes cross the region of the internal os. These vessels occupy a position in front of the presenting portion of the fetus. Rupture of the membranes may be accompanied by rupture of the fetal vessel, causing fetal blood loss and possible exsanguination.

PPH is the most common cause of serious bleeding in obstetric patients and one of the leading causes of maternal death. It is sometimes defined as blood loss in excess of 500 mL during the first 24 hours after delivery, although the estimation of blood loss is notoriously inaccurate, and the loss of 500 mL after vaginal delivery or 1000 mL after cesarean delivery is quite common. The most common causes of PPH are uterine atony and laceration of the vagina or cervix. There are many causes for uterine atony: complications of general anesthesia, overdistention of the uterus by a large fetus or multiple fetuses, prolonged labor, rapid labor, augmented labor, high parity, retained products of conception, coagulation defects, sepsis, ruptured uterus, chorioamnionitis, and drugs such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and magnesium sulfate. It has been estimated that PPH occurs in 1% to 5% of all deliveries, depending on the definition used.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. Number 60, March 2005. Pregestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:675.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. Number 78, January 2007 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 64, July 2005): Hemoglobinopathies in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:299.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Committee on Adolescent Health Care, ACOG Working Group on Immunization: Number 467, September 2010 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 344, September 2006): Human papillomavirus vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:800.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women & Committee on Obstetric Practice. Number 471, November 2010 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 316, October 2005). Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1241.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Committee on Genetics, Number 486, April 2011 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 325, December 2005). Update on carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:14.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Number 504, September 2011. Screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:751.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Committee on Genetics. Number 527, June 2012. Personalized Genomic Testing for Disease Risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1318.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Number 549, January 2013 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 315, September 2005). Obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:213.

Centers for Disease Control. National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Reports. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/nvsr.htm [Updated January 24, 2013. Accessed March 4, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Births and natality. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm [Updated January 18, 2013. Accessed March 4, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen births. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/teenbrth.htm [Updated January 18, 2013. Accessed March 4, 2013] .

Chang J, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance: United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(SS1-SS2):1.

Dawes MC, Ashurst H. Routine weighing in pregnancy. BMJ. 1992;304:487.

Floyd LR, et al. Recognition and prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1059.

Johnson K, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care—United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-06):1.

Santelli JS, et al. Can changes in sexual behaviors among high school students explain the decline in teen pregnancy rates in the 1990s? J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:80.

Santelli JS, et al. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: a review of US policies and programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:83.

Santelli JS, et al. Recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: More abstinence or better contraceptive use? Am J Pub Health. 2007;97(1):150.

1 The author thanks Siobhan M. Dolan, MD, MPH, Associate Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, who reviewed the chapter for this edition.

2 Disparity between the size of the maternal pelvis and the fetal head, which precludes vaginal delivery.