1 The Practice of Pediatric Anesthesia

Preoperative Evaluation and Management

Parents and Child

Anesthesiologists must assume an active role in the preoperative assessment of children. Ideally, the anesthesiologist performing the preoperative evaluation will also anesthetize the child. A complete medical and surgical history; family history; medical record review; evaluation and review of laboratory, radiologic, and other investigations; and physical examination are performed on every child who is to be anesthetized (see Chapter 4). When appropriate, the child should receive preoperative medical therapy to optimize his or her medical condition or conditions (e.g., children with seizure disorders or reactive airway disease) before receiving anesthesia. In addition, the emotional state of the child and family must be considered and appropriate psychological and, if necessary, pharmacologic support provided. The anesthesia team, working in concert with surgical colleagues, nursing, and child-life specialists, should find appropriate and creative techniques (e.g., use of videotapes, booklets, hospital tours, and trained paramedical personnel) to prepare the child and family. The marked increase in the number of outpatient surgical procedures has reduced the time available for interaction among the anesthesiologist, the family, and the child. Despite this reduced contact time, these support techniques should not be neglected.

Familiarity with a child’s clinical and psychological status as well as the parental concerns is essential to delivering quality anesthesia care. To achieve the very best outcome for each child, it is essential to meet with the child and the parents (or caregiver or legal guardian) together and establish rapport preoperatively. There are many developmental issues that surround the hospital experience: for example, teenagers fear loss of control, awareness, and pain; younger children fear mutilation from their surgery; and toddlers fear separation from their parents (see Chapter 3). However, for children who are old enough to understand (usually age 5 years and older), it is reasonable to explain in simple terms what anesthesia involves and what will transpire on entering the operating room. It is vital to speak directly to the child because he or she is the person having the surgery. Children at the age of reason have the same fears as adults, but have greater difficulty articulating them. It is important to explain the differences between “sleep” from anesthesia medicine and the sleep they get at home. Even if they undergo anesthesia for hours, they will feel as if they were unconscious for only the time it takes to blink the eyelids once. Many children are also fearful of awakening during the surgery and others are fearful of not awakening at the end of surgery. Children require reassurance that they will not feel anything during surgery, that they will not wake up during the procedure, and that they will awaken at the conclusion of the surgery.

1. As your child is anesthetized, the eyes may roll up: “You might see your child’s eyes roll up and this is completely normal and happens to all of us when we fall asleep; it is just that we are not looking for it.”

2. “As people fall asleep they often make snoring noises and other noises from their throat; if your child does this it is completely normal.”

3. “As the anesthetic reaches the brain, the brain sometimes gets excited and causes movement of the arms and legs that are without purpose, or it may cause them to turn their head from side to side. This means the anesthetic is having its effect and even though your child appears to be partly awake, he (or she) has received enough anesthesia to ensure that he (or she) does not remember this.”

4. “If your child becomes frightened, we will increase the amount of the anesthesia medicine rapidly and calm your child as quickly as possible.”

5. If the child is to have an IV induction, then informing the parents that the child might suddenly look pale and that the start of anesthesia will be very rapid is also helpful so as to avoid confusion about what the parents will observe.

These preemptive explanations are important to undermine the parents’ anxiety at a time when you need to focus on the child. It is common for parents to decline to be present during induction once they hear these explanations. Finally, it is prudent to reassure the parents that for surgeries that are emetogenic and in children who have been or are prone to emesis, that appropriate prophylactic therapy will be administered before the child recovers. Similarly, explain to them that if pain is anticipated, it will be managed aggressively in the operating room and in the recovery room. Anesthesiologists can provide valuable assistance in this respect because of their knowledge of the pharmacology of sedative and opioid medications (see Chapter 6), as well as their ability to perform neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks (see Chapters 41 to 43). The possible need for postoperative intensive care, including assisted ventilation, should be anticipated and fully discussed with the parents and child (if the child is of an appropriate age). If special monitoring is required in the operating room or postoperatively, this should be explained and the child assured that the IV catheters, airway devices, and all invasive monitoring devices will be placed after induction of anesthesia to avoid causing discomfort and will be removed as soon as the child’s postoperative condition permits.

The Anesthesiologist

Anesthesiologists must fully understand the proposed surgical or investigative procedure to facilitate the planning of an appropriate level of monitoring and selection of anesthetic drugs and technique. The anesthesiologist must anticipate the needs of the surgeon or proceduralist in terms of positioning the child, the need for or avoidance of muscle relaxants, considerations regarding specific procedures (e.g., the surgeon’s need for motor and sensory evoked potentials may influence choices of anesthetic technique), IV fluid and blood product management (see Chapters 8 and 10), as well as the need for strategies to alleviate perioperative pain and anxiety. For complex cases, the anesthesiologist and surgeon should formulate a plan preoperatively and explain the plan to the parents and child. All important medical issues that require clarification should be investigated during the preoperative evaluation and planning process. It is useful to discuss your concerns with the appropriate medical consultants (e.g., the neurologist for the management of seizure medications in the perioperative period, the hematologist for the child with hemophilia, and others as indicated). To maximize the benefit from these consultations, it is important to focus on the specific anesthetic or medical issue of concern. Consultant recommendations must be carefully reviewed and should reflect the consultant’s understanding of the anesthesia process and what it is that you require regarding the child’s medical condition that will assist you in the delivery of anesthesia (see Chapters 11, 14, 22, 25, 26, and 28).

All children should be fasted preoperatively. Infants must receive special consideration; prolonged abstinence may lead to dehydration or hypoglycemia (see Chapters 4 and 8). Children may surreptitiously circumvent the preoperative fasting orders, especially if the period of fasting is prolonged or other children in the vicinity are in possession of food. One must always be prepared for the possibility of a full stomach and its sequelae. For example, the risk of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents is increased in some children (e.g., who are obese and who had previous esophageal surgery, difficult intubation, or hiatal hernia). In these children, the anesthetic management should be modified to minimize the risk of regurgitation and aspiration. Preoperative consideration must be given to proper psychological support, appropriate premedication, and the timing of the premedication (see Chapters 3 and 4). Psychological support of the child and parents must never be neglected, no matter how calm they might appear. Premedication may be administered on the ward or in the waiting area; however, once any medication is administered, the child must be observed for compromise in cardiopulmonary function. If the child is premedicated on the ward, transport to the operating room must be undertaken with caution and with appropriate monitoring. A critically ill child must be accompanied by skilled staff who will ensure continued infusion of vasoactive medications and who are skilled in the management of any emergencies that could arise during transport (see Chapter 38). In some, premedication may be omitted because of the critical nature of a child’s illness or because a child is especially cooperative.

Informed Consent

“The risks of anesthesia are generally proportional to the health of the child. For example, if a child has a heart, lung, or kidney disorder, etc., then the risk from anesthesia is increased. In your child’s case these are our concerns” (and then elaborate the particular patient’s issues, such as reactive airway disease, apnea of prematurity, etc.). “Knowing these problems ahead of time may reduce the anesthetic risk for your child because we can modify our anesthetic prescription according to your child’s specific needs. However, there is always the possibility of allergic or unusual responses to anesthetic medications that we cannot predict, and that is why I shall carefully observe and monitor your child as I have described.”

“The risks of anesthesia are generally proportional to the health of the child. For example, if a child has a heart, lung, or kidney disorder, etc., then the risk from anesthesia is increased. In your child’s case these are our concerns” (and then elaborate the particular patient’s issues, such as reactive airway disease, apnea of prematurity, etc.). “Knowing these problems ahead of time may reduce the anesthetic risk for your child because we can modify our anesthetic prescription according to your child’s specific needs. However, there is always the possibility of allergic or unusual responses to anesthetic medications that we cannot predict, and that is why I shall carefully observe and monitor your child as I have described.”

If a child is critically ill or has a disease process that is an immediate threat to his or her life, then this must be explained to the family. If a parent asks about the mortality risk, then all one can say is that the mortality related to anesthesia in most advanced countries is very small, less risky than crossing a busy thoroughfare on foot. Statistically, the incidence varies from one in several hundred thousand for healthy children undergoing routine procedures to a much greater rate for those who are critically ill. Nonetheless, the mortality for any specific child cannot be predicted with certainty. Recent concerns regarding possible anesthetic agent–induced neurotoxicity (see Chapter 23) has become a common question from parents of neonates or toddlers. Again, reassurance regarding the lack of substantive human data, the importance of our monitors, and our experience will help allay their concerns.

Operating Room and Monitoring

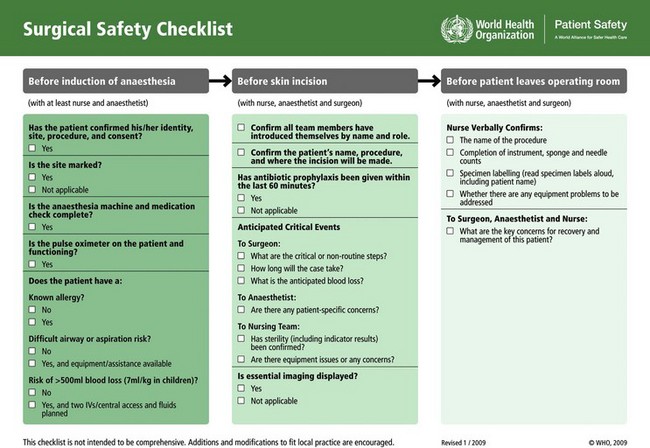

For the anesthesiologist to successfully carry out a proposed anesthetic plan, the child’s medical record must be examined for pertinent information before induction of anesthesia. For children who have already been assessed preoperatively, the record should be reviewed again for new information that may have been added since the initial evaluation. It is most important that the child’s identification bracelet is checked, especially if the anesthetizing team is different from the preoperative evaluation team. A “time-out” and checklist for nurses, surgeon, and anesthesiologist to confirm the child’s name, the planned surgical procedure, and the site of the surgical procedure (right or left side or bilateral); airway concerns; the need for prophylactic antibiotics; allergies and anaphylaxis; and availability of special equipment and large IV access are also reviewed. This review constitutes a vital safety net that we provide in the operating room (Fig. 1-1). All equipment for induction and maintenance of anesthesia, including suction and all necessary monitoring devices, must be functioning and reliable (see Chapter 51). Equipment must be checked by the anesthesia team before induction of anesthesia.

FIGURE 1-1 WHO Surgical Safety Checklist.

(From World Health Organization, Geneva, 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/en/)

The monitoring should be appropriate for the child’s clinical condition and surgical procedure. In every situation, basic monitoring is essential; to this are added special monitoring devices as they become necessary. The basic monitors are the anesthesiologist’s eyes, ears, and hands, which confer the ability to observe a child’s color and chest movements, to listen for heart tones and breath sounds, and to palpate the arterial pulse and temperature of the skin. A precordial or esophageal stethoscope is a very useful and simple device that allows constant assessment of heart tones and the quality of breath sounds even when our attention is focused away from physiologic monitors. All children, except those undergoing the briefest noninvasive procedures, should have IV access to allow for fluid administration and to provide a route for rapid and predictable drug administration. If IV access is already in place, it is essential to ensure its functionality and size before anesthesia is induced. Fluid replacement with balanced salt solution is particularly important in children who have undergone prolonged fasting or who have ongoing third-space losses, although glucose-containing solutions may be preferable under specific circumstances (see Chapter 8). Continuous monitoring of the electrocardiogram, temperature, inspired oxygen concentration, oxygen saturation, expired carbon dioxide, and intermittent blood pressure determination are considered routine. Expired carbon dioxide monitors (especially those that display the waveform) and pulse oximetry are extremely important in the early detection of potential anesthetic-related events that, if undetected, could result in serious morbidity or mortality. Identifying the anesthetic agent and monitoring its concentration breath by breath is also helpful but not mandatory. The role of wakefulness-monitoring devices in children remains unestablished, especially in children who are younger than 2 years of age (see Chapters 6 and 51). Near infrared spectroscopy is being used increasingly during cardiac surgery; it provides a useful monitor of cerebral (i.e., organ) oxygenation.

Invasive monitoring procedures are sometimes forsaken in a child because inexperience with pediatric techniques causes the anesthesiologist to dismiss these procedures as being “excessive.” These monitors, however, allow the accurate measurement of blood pressure, cardiac output, filling pressures, and cardiac and pulmonary function. In turn, they provide a safe mechanism for assessing the response to pharmacologic interventions, as well as the responses to administration of blood products, fluids, and vasoactive medications (see Chapter 48).

Induction and Maintenance of Anesthesia

Significant differences in the physiology and behavior of a child, especially a neonate, in comparison with an adult, mandate that the anesthesiologist not consider a child merely a small adult. In an infant, the rate of uptake of inhalation anesthetic agents is more rapid than in an adult. An infant’s response to most oral and IV medications is also different; therefore, if changes need to be made, the inspired concentration of an inhalation agent should be adjusted more gradually and the doses of medication diluted and titrated more carefully than in older children and adults (see Chapter 6).

Airway and Ventilation

The most important consideration in the safe practice of pediatric anesthesia is attention to the adequacy of the airway. Airway obstruction occurs readily because of the unique characteristics of the infant and child airway (see Chapter 12). Thus the anesthesiologist must maintain constant vigilance of the airway to ensure that it remains clear at all times. Airway obstruction may lead to hypoventilation, although the causes of hypoventilation may be central (opioids or inhalation agents) or peripheral (muscle relaxants) in origin. Thus anesthesiologists must always place emphasis and attention on constantly monitoring the adequacy of ventilation, particularly when administering anesthesia via a facemask. This is necessary because the expired carbon dioxide tension may underestimate the true carbon dioxide tension as a result of a poor mask fit with air leaks, in combination with an obstructed airway. The capnogram is usually very accurate during mask anesthesia with a circle breathing circuit. Failure to detect an appropriate end-tidal carbon dioxide tension suggests inadequate ventilation, a mask leak, or reduced pulmonary blood flow, with the result that the child’s condition may deteriorate from lack of an adequate airway or dilution of the anesthetic gas concentrations.

Fluids and Perfusion

Appropriate intraoperative fluid management is especially important in infants and children. Because of the relatively small blood volumes of infants and children, hypovolemia may develop rapidly after what may appear to be a trivial amount of blood loss. Fluid shifts may occur in infants because they were fasted for a prolonged period preoperatively. Replacement of lost blood and basic fluid administration must be carefully titrated (using rate-limiting devices), because overhydration readily occurs. The anesthesiologist should have a clear plan for the type and volume of fluid for perioperative administration. Preoperative calculation of maintenance, deficit, and potential third-space losses helps in formulating this fluid management plan, although for children beyond 1 year of age, the fluid replacement strategy has been greatly simplified. A well-planned outline results in a rational and safe approach both to fluid maintenance and to correction of fluid deficit and losses (see Chapters 8 and 10). The anesthesiologist should have immediate access to indwelling IV cannulae; obstructions in the line, loose connections, disconnections, or interstitial cannulae result in children not receiving intended fluid therapy or medications, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

The Postanesthesia Care Unit

On arrival in the PACU, a clear summary of the medical and surgical problems of the child; important intraoperative events; timing of antibiotics, analgesics, local anesthetics, or nerve blocks; and details of the anesthetic procedure are given to the PACU personnel. The PACU must be equipped with age- and size-appropriate resuscitation equipment. Vital signs (oxygen saturation, heart rate, blood pressure, respirations, temperature, and pain score) should be recorded on admission to the PACU and at appropriate intervals during the child’s stay (see Chapter 46). If appropriate, specific instructions should be given relating to fluid management; the administration of oxygen, analgesics, antiemetics, and other medications; blood tests (e.g., hematocrit, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation profile); and radiographs. Once the anesthesiologist is certain that the child is stable from a cardiopulmonary standpoint and that all vital information has been provided to the PACU staff, the anesthesiologist should inform the parents that the child has arrived safely in the PACU, provide them with a summary of the anesthetic procedure, and then proceed to the next case. If the child requires special attention (airway issues, hypotension, possible ongoing blood loss, etc.) in the PACU, then the anesthesiologist should reassess the child personally before the child is discharged.