CHAPTER 17 The Postpartum

POSTPARTUM CARE OF THE MOTHER

On Crete, right after a baby is born, it is given chamomile tea. The mother’s breasts and nipples are washed with chamomile tea before she nurses. When visitors come to the hospital to see the new baby, the first question they asked is “has she/he drunk the chamomile yet?” The tea is considered the perfect thing for both mother and child after the excitement of labor. Once the baby had had its first chamomile, it is a huge relief to everyone because it is a sign that they are healthy and now part of the clan. In the hospital near the village I live in part of the year, there is a special room for brewing chamomile for the new mothers and babies.1

REDEFINING POSTPARTUM IN A WOMAN-CENTERED WAY

Societal expectations also revolve around this arbitrarily allotted 6-week period. Many employers expect women to be back to work after 6 weeks; obstetricians’ and midwives care packages end at 6 weeks; and even husbands, other relatives, and friends expect mom to be able to cope on her own by then. Yet most women, when given the opportunity to express their feelings about their postpartum experience say that they needed more help, support, care, guidance, and understanding than they received, and for much longer than 6 weeks after birth (Box 17-1). Most mothers say that they don’t really begin to feel like their old selves for at least 6 to 8 months after birth, and many never feel quite like their old selves again. Most admit that they had feelings of profound joy as well as stress, anxiety, and confusion during those early days, weeks, and months of becoming a mother.

Postpartum women experience a significant rate of physical health problems; however, little attention has been given to research in this area beyond recent research into postpartum depression.1,2 Substantial postpartum morbidity is known to exist and this is not routinely assessed as the postnatal assessment.3 In a study of 11,701 postpartum women, nearly half had health problems within 3 months after the birth that continued for more than 6 weeks, and that they had never experienced before. The symptoms of ill health that they confronted sometimes lasted for months or years afterward, and many of them never told their doctors about their problems.2 In general, the cursory nature of postnatal care does not facilitate the intimacy required for women to express the nature of their physical complaints, and thus most obstetricians have not recognized the extent to which postpartum women experience health complaints. Interestingly, recent studies have questioned the effectiveness of postpartum medical visits in meeting the postpartum health needs of mothers, and have concluded that “the present six week postnatal examination does not appear to meet the health needs of women after childbirth: its content and timing should be reviewed.”3

Postpartum visits should focus on the challenges women face during this time, and should provide women with the opportunity to express their concerns and expectations, both physically and emotionally. In Reactions to Motherhood: The Role of Post-Natal Care, midwife Jean A. Ball states:

The main focus of postnatal care has traditionally been that of ensuring the physical recovery of the mother from the effects of pregnancy and labor and establishing infant feeding patterns.… The emotional and psychological needs of mothers have not received much attention until recently and there has been an assumption that these needs will automatically be met if the first two aspects of care are satisfied. The organization of postnatal care has accordingly been based upon this premise.4

According to a study by Buchart et al., “Listening to women is an essential element in the provision of flexible and responsive postnatal care that meets the felt needs of women and their families.”5 By developing an open dialogue with women during pregnancy, care providers can help women to realistically prepare for the postpartum prior to birth, and overcome difficulties that might be inhibiting their recovery as well as their experience of motherhood. This chapter highlights the need for extensive family and social support for the mother after birth in the prevention of this potentially devastating problem. It must be recognized, however, that the need for such support is not limited to the prevention of PPD, but for the promotion of the overall wellness of the new mother, and by extension, her child and family. Indeed, many postpartum difficulties can be averted with adequate postpartum support of the mother, both from her immediate personal community (family, friends, coworkers, etc.) and from her health care providers.

THE USE OF HERBS FOR POSTPARTUM CARE

The use of medicinal herbs has been an intrinsic part of postpartum care in cultures throughout the world. Herbal teas and other preparations are given for a variety of reasons, including preventing infection, treating colic, and nourishing the mother and child. Herbs have been used both internally and topically to reduce bleeding, ease pain from cramping, increase breast milk production, heal and soothe the perineal area, and relax the mother. 6 7 8 9 10 References to traditional herb use after birth abound in historical and sociological references, although the ethnobotany is often not specific. For example, women in Thailand have been known to drink a mixture of tamarind, salt, and water to “strengthen the womb,” whereas women of the Seri Indian tribe of Mexico drank “seep willow tea” to “stop bleeding after birth.”11 The Jicarillo women chewed the root of wild geranium to assist in “expelling uterine blood.”11 Herb use was common in Colombia and Jamaica, as it was in Southeast Asia.12 In Burma, a paste of tumeric is rubbed onto the body to prevent blood stasis and encourage good circulation while expelling the afterbirth blood.12 In Micronesia, women are given baths of tumeric paste after birth.1 In both Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine, herbs are a routine aspect of postpartum care, and have been for thousands of years.

There is little evidence on the number of women in the United States using herbs for postpartum complaints; however, it is likely consistent with the volume of herb use during pregnancy, or slightly higher, as the use of herbal teas for increasing lactation is very popular, and women and care providers are often less hesitant to use herbs outside of pregnancy. Numerous articles appearing in nursing, medical, and midwifery journals describe the use of herbs for postpartum care. 6 7 8 9 10 Chapters 12 and 18 discuss the safety of herb use during lactation. The remainder of this chapter presents information on treatments for common postpartum problems.

COMMON POSTPARTUM COMPLAINTS

After birth women experience a number of common physiologic changes that can lead to discomfort (e.g., sweating, engorged breasts, after birth pains), problems resulting from pregnancy or birth (e.g., hemorrhoids), and discomforts associated with breastfeeding (e.g., engorgement, sore nipples). Hemorrhoids are discussed in Chapter 5, and problems associated with lactation in Chapter 18.

After Pains

After pains are associated with the normal process of uterine involution—the return of the uterus to its pre-pregnant size. Involution involves the clamping down of the uterine myometrium, a process that is accompanied by menstrual cramp–like pain that varies from mild to very severe. Many women turn to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen to relieve the discomfort, whereas others, preferring not to use pharmaceuticals while breastfeeding, turn to herbs. Herbs such as cramp bark (Viburnum opulus), black haw (Viburnum prunifolium), and motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) are excellent choices as they are both antispasmodic and uterotonic.13,14 This is important as uterine laxity might actually exacerbate the contractions as the uterus tries to involute. The herbs facilitate the physiologic process while providing relief of cramping and possibly, with the viburnums, mild analgesia. Simple teas such as catnip (Nepeta cataria) and chamomile (Matricaria recutita) have empirically been shown to be effective as teas, when combined with the preceding tinctures, providing and apparently synergistic effect when used together.15 for mild cramping with tinctures of cramp bark, black haw, and/or motherwort added for severe discomfort.

A popular treatment among independent midwives for the relief of after pains, and for supporting recovery of the pelvic organs and “qi” of the body after childbirth is the use of the traditional Chinese medicine practice of moxibustion (Box 17-2). This technique, previously discussed for turning a breech baby when applied to acupuncture points on the small toe, is applied to the lower back and abdominal area over the uterus to warm the mother, reduced pain, and support involution. It is repeated once or twice daily, for 30 minutes, for the first week after birth, usually starting on day 2 or 3 postpartum.

BOX 17-2 Moxibustion for Essential Postpartum Care

To Give a Moxibustion Treatment

POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION

Postpartum depression is a crippling mood disorder, historically neglected in health care, leaving mothers to suffer in fear, confusion, and silence. Undiagnosed it can adversely affect the mother–infant relationship and lead to long-term emotional problems for the child. I have described it as ‘a thief that steals motherhood.’16

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a potentially devastating mood disorder thought to affect approximately 15% but as many as 28% of new mothers, with an estimated 400,000 women suffering from this condition annually. Twenty-five percent of these women are likely to develop PPD in the first 3 months postpartum and 25% of these women are at increased risk of developing severe, chronic depression. PPD generally has a slow and insidious onset, beginning at 2 to 3 weeks postpartum; however, it can occur anytime in the first year postpartum, and may last up to a year or longer. Symptoms of PPD include irritability, depression, guilt, hopelessness, chronic exhaustion, despair, feelings of inadequacy, insomnia, agitation, loss of normal interests, joylessness, difficulty relaxing or concentrating, memory loss, confusion, inability to function, emotional numbness, inability to cope, irrational concern with baby’s well-being, and thoughts of hurting oneself or baby (Box 17-3). Women with postpartum depression may become obsessed by the terrifying feeling that their depression and anxiety are interminable. They may feel extremely detached from their family, including husband, baby, and other children. They may be plagued by fear of hurting the baby, causing them panic and anxiety, leading them to distance themselves from the baby, and exacerbating feelings of inadequacy as a mother; thus, it has been described as “a thief that steals motherhood.”16,17

Despite multiple visits to care providers in the postpartum period, postpartum depression often goes unrecognized by the obstetrician or midwife, with symptoms of depression commonly dismissed as “just the baby blues” leaving women in need of treatment and care with none, and prolonging the terrible desperation they feel without an explanation.16, 18 19 20 Undiagnosed PPD can adversely affect the mother–infant relationship and lead to long-term emotional consequences for both.16 For most women, a diagnosis of postpartum depression comes as a welcome relief—putting their experience into the context of an explainable illness for which there is treatment. It can provide a framework that helps them, as well as their family, begin to make sense of what is happening. It is essential that care providers learn to recognize the many symptoms and manifestations of PPD to ensure that it is recognized and that women receive adequate support and treatment.21

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS FOR PPD

Despite its prevalence, the etiology of PPD remains unknown.22 Smokers are at increased risk for PPD.23 In a survey of 574 women in Ontario, of whom 9.9% were diagnosed with PPD, there was a higher rate of PPD among women with a prior history of depression, among women whose pregnancy was unplanned, among those who described the course of pregnancy as “difficult,” and among women who described their general health as “not good.”24 Women with a history of premenstrual dysphonic disorder (PMDD) may also be at increased risk.25 Breastfeeding mothers may be significantly less likely to develop postpartum depression than non-breastfeeding mothers, and breastfeeding may have unknown protective biological factors against PPD.23,26,27 A recent revision of the predictive factors for PPD lists prenatal depression, child care stress, life stress, lack of social/marital support, prenatal anxiety, low marital satisfaction/poor relationship, history of depression, a difficult infant temperament, maternity blues, low self-esteem, low socioeconomic status, single motherhood, and unplanned/unwanted pregnancy as the most important risk factors for PPD. 28 29 30 31 32 33

Many hormones have been investigated for their possible causative roles, and PPD is commonly attributed to the rapid change in hormones in the postpartum period; however, the role of hormones in PPD remains inconclusive.22,34 PPD has also been attributed to thyroid insufficiency (hypothyroidism), which is commonly found in the 2 to 5 months after birth. Recent research suggests that the abrupt physiologic drop in insulin levels that occurs during the postpartum period after the slow rise throughout pregnancy may induce mood disorders by affecting serotonin secretion in the brain. Low blood sugar can also have a dramatic effect on mood; therefore, postpartum women must ensure adequate caloric intake through a well-balanced diet to minimize the risk of depression resulting from hypoglycemia. It has been suggested that a carbohydrate-rich diet in the postpartum period may be a preventative or adjunctive treatment of postpartum mood disorders.22 Inadequate intake of essential fatty acids, protein, B vitamins, zinc, and iron also have been associated with PPD. Women who have experienced significant blood loss at birth may be predisposed to depression caused by anemia and its accompanying increased fatigue, tendency to infection. Fatigue also appears to be highly correlated with PPD, especially persistent fatigue occurring by day 14 postpartum.35

Lack of social and emotional support during pregnancy, the labor and birth, and in the postpartum period have all been associated with an increased risk of developing PPD. One PPD study found that poor support with newborn care showed a positive correlation with PPD, whereas affiliation with a secular group was a positive preventative factor.36 A study looking at the impact of a supportive partner in the treatment of PPD found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms in the group where the partner provided the mother with significant support, whereas another discovered that women with postpartum depression “reported less practical and emotional support from their partners and saw themselves as having less social support overall.”37 Clearly, adequate social support is an important variable in preventing postpartum depression. Even a therapist can lead to significant improvement in PPD. In one study, interpersonal psychotherapy was demonstrated to reduce depressive symptoms, improve adjustment, and was shown to be an alternative to drug therapy, especially for breastfeeding mothers.38 It is important for women who are experiencing extreme or prolonged symptoms to seek help.

A study conducted in Switzerland found that among the most significant risk factors for postpartum depression are social or professional difficulties, deleterious life events, early mother–child separation, and negative birth experience.39 Birth experience may have a dramatic impact on a woman’s self-perception as she enters motherhood, yet is generally overlooked. Assisted delivery (cesarean, forceps, and vacuum extraction) may be associated with higher rates of postnatal depression, as are bottle-feeding, dissatisfaction with prenatal care, having unwanted people present at the birth, and lacking confidence to care for the baby themselves after they leave the hospital.40,41 A study by Edwards et al. indicated that there is an increase in rates of postpartum depression among women who have had cesarean sections, a finding that women themselves report.42,43 Although this finding has been debated, clinical experience suggests that disappointment in the birth experience effect a new mother’s self-confidence. Considering that 25% to 40% of American women now deliver by cesarean section, this certainly illuminates the need to both reduce cesarean rates and provide counseling and support for those women who have birthed operatively. Furthermore, one study indicates that women who were cared for by midwives had lower rates of depression in the postnatal period, whereas another study revealed a significantly lower rate of depression among the women who had given birth at home compared with hospital vaginal delivery.44 Women reported that a sense of control and being informed about choices in their health care greatly improved their psychological state.

Few women experience all of the symptoms of PPD; some may exhibit only a few, some many. It is the duration, severity, and complexity of the symptoms that distinguishes postpartum depression from the common and normally occurring “baby blues,” which occurs in 50% to 70% of new mothers. Baby blues is thought to be a result of normal postnatal hormonal and other physiologic adjustments, and is self-limiting, usually beginning at about day 3 or 4 postpartum and lasting only up to about 14 days.45 Symptoms include crying, irritability, fatigue, anxiety, and emotional lability.16 Further, the baby blues tends to be punctuated by periods of elation, whereas postpartum depression lacks the elation and the periods of depression are more intense and prolonged. Women with baby blues require support and reassurance but no treatment is necessary, although attention to nutrition, sleep, and support are essential. If symptoms persist past 2 weeks, depression should be ruled out.

Postpartum psychosis is an extreme postpartum mood disorder, occurring in 1% to 2% per 1000 new mothers, usually having its onset a few weeks but up to 3 months after birth, occurring most often in primiparas, and being more likely to require hospitalization for treatment. Other mood disorders than can occur in the postpartum period include panic attacks, postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder, postpartum traumatic stress disorder, and postpartum bipolar disorder.16

PREVENTION OF PPD

Many care providers are afraid to talk to women prenatally about postpartum depression, thinking it might frighten them. In fact, a woman will be better prepared to recognize the need for help and get it if she is informed that this could happen ahead of time. According to Jane Honikman, founder of Postpartum Support International, “Ignorance and denial are the two greatest barriers to this problem.”1 Many women enter pregnancy and become mothers with an unrealistic and romanticized picture of motherhood. There are also tremendous social pressures on women to conform to the image of being happy and grateful. Yet, new motherhood can also bring fatigue, feelings of being overwhelmed and inadequate, a sense of social isolation for women who have abandoned previous social or work activities to be home with the baby, and body image issues as a result of changes that occurred during pregnancy and accompanying lactation. Social pressures on mothers strongly contribute to many mothers’ sense of inadequacy—leaving them feeling that “everyone else does it better than I do, and is happy, why can’t I?” Single mothers face additional burdens, concerns, and fears unique to the task of raising a baby alone.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

The biggest problem with treatment for postpartum depression is the uncertainty about causative factors. There is no consensus on the use of hormonal therapy in the treatment of PPD.34 The safety of maternal use of psychotropic medications while breastfeeding is controversial. In 2001, expert consensus guidelines for the treatment of depression in women were published. The expert panel concluded that few studies published evaluate pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatments for PPD. Antidepressant medications and psychosocial interventions were recommended as first-line treatments regardless of the mother’s breastfeeding status, with the exception of treatment of minor depression, for which the use of antidepressants was considered warranted only if the woman was not breastfeeding. A 2001 comprehensive review by Burt and colleagues that looked at the use of psychotropic medication in breastfeeding women since 1955 found no controlled studies evaluating safety.46 In contrast, Hale suggests that many of these drugs are well-studied and safe, although demonstrates that most do enter breast milk in varying quantities and may cause side effects in the infant, including sedation, somnolence, respiratory arrest, colic, jitteriness, and withdrawal.47

There is emerging data suggesting risk of antidepressants to the infants of nursing mothers using SSRIs; therefore, it is essential that a careful plan of treatment be considered for mothers committed to breastfeeding. Chambers et al. identified an association between maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) use in late pregnancy and persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPH) in the newborn. The authors stated, “Although our study cannot establish causality, several possible mechanisms suggest a casual association is possible.”48 Another physician writes:

Any drug that affects infant growth, in or ex utero, should be regarded with suspicion and should not be written up as a recommendable solution for postpartum depression, comparable with innocuous and effective methods such as psychotherapy, nurse home visits, and group therapy. The available evidence indicates that even when infant serum levels are low or undetectable, side effects may occur. There is an ample body of evidence that SSRIs taken during pregnancy cause neonates to suffer withdrawal symptoms, which all by itself is a matter for concern. Postpartum depression is an issue that should not be taken lightly, but, as history shows, the short-term benefits of drugs that have not been sufficiently studied do not weigh up against the tragic long-term disasters they might provoke.49

Nonpharmacologic treatments for PPD can be effective primary treatments depending upon the severity of symptoms and the woman’s ability to comply, and can be used in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Nonpharmacologic treatments include psychosocial supports, psychotherapy (individual and/or couple), group therapy, and/or medications. Attention to nutrition, fluid, sleep, and social support status, are essential.34 Many women turn to alternative therapies for PPD, concerned about the risk of pharmacotherapy while nursing. Alternative therapies can constitute part of effective adjunct treatment for PPD.50 Therapies to consider include nutritional and herbal supplements, aromatherapy, acupuncture, and both maternal and infant massage. These are discussed under Nutritional Considerations and Additional Therapies.

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

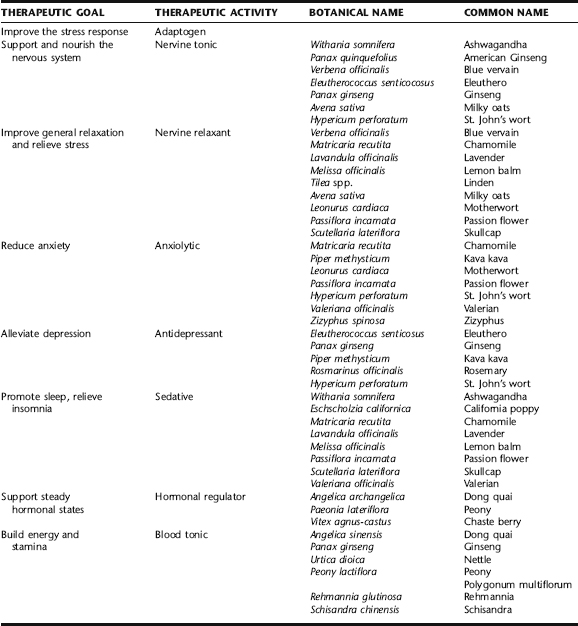

Herbal remedies are the primary pharmacologic therapy for the treatment of depression in many European countries, and are increasingly being recognized in the United States as safe and effective alternatives to many psychotherapeutic medications for mild to moderate depression and anxiety (Table 17-1). Herbs such as St. John’s wort, kava kava, lavender, lemon balm, passion flower, and valerian have been used in the treatment of a number of mood disorders including depression, anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, and irritability.51,52 Herbs, such as many adaptogens, can also be used to treat fatigue, nervous exhaustion, hormonal dysregulation, and blood sugar dysregulation. Unfortunately, almost no studies have been conducted on the safety and efficacy of herbs for the treatment of postpartum depression, or the safe use of herbs during lactation.

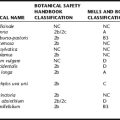

The application of herbs for the treatment of postpartum depression is largely extrapolated from traditional herbal treatments for general depression. The use of adaptogens in this context is predicated on their marked ability to improve the stress response, and via the HPA axis, to regulate cortisol and blood sugar levels, an important adaptation during times of increased and prolonged stress, as new motherhood is for many, and especially so for those at risk of PPD. Safety is an important concern when herbs are to be applied prophylactically during pregnancy for women with a history of PPD, and during lactation, especially for a prolonged period as is often necessary with PPD. Table 17-2 ranks these herbs according to the scale developed by Hale (Table 17-3) for the evaluation of drugs for the treatment of PPD during lactation and modified by this author for relevance to herbal medicine. When there is a history of previous PPD, it is best to focus on preventive nutritional strategies during pregnancy, as well as ensuring that proper social supports are in place, and reserving the use of herbs to the postpartum period for optimal safety to the fetus. Nutritional and social/psychological strategies can be continued postnatally, and herbal interventions begun immediately after birth with a history of PPD, or even prophylactically for a woman with significant risk factors for developing PPD. In women with no history or risk factors, or who present at their first appointment with symptoms, herbs can be started as needed.

TABLE 17-2 Safety of Herbs for PPD during Pregnancy and Lactation

| HERB | RISK CATEGORY DURING LACTATION* | RISK DURING PREGNANCY† |

|---|---|---|

| American ginseng | See ginseng | |

| Ashwagandha | L1 | B1 |

| Blue vervain | No data | Unknown |

| California poppy | L2/L3 | B2 |

| Chamomile | L1/L2 | A |

| Chaste berry | L2 | B1 |

| Dong quai | L2/L3 | C |

| Eleuthero | See ginseng | |

| Ginseng | L1/L2 | A |

| Kava kava | L3–L5 | B1 |

| Lavender | L1/L1 | B2 |

| Lemon balm | L1/L2 | B2 |

| Milky oats | L1/L2 | B1 |

| Motherwort | L1/L2 | B3 |

| Nettle | L1/L2 | B2 |

| Passion flower | L1/L2 | B1 |

| Peony | L2/L3 | B1 |

| Rosemary | L2 | B1 |

| Schisandra | No data | B1 |

| Skullcap | L1/L2 | B2 |

| St. John’s wort | L2/L3 | B1 |

* See Table 17-3 for ranking scheme.

† See Chapter 13 for Mills and Bone/TGA classification scheme for herb safety during pregnancy.

Data from Blumenthal M: The complete German Commission E monographs: therapeutic guide to herbal medicines, Austin, American Botanical Council, 1998; Mills E, Duguoa J, Perri D, et al.: Herbal Medicines in Pregnancy and Lactation: An Evidence-Based Approach, Boca Raton, Taylor and Francis, 2006; Mills S, Bone K: The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety, St. Louis, Churchill Livingstone, 2005; Basch E, Ulbricht C: Natural Standard Herb and Supplement Reference: Evidence-Based Clinical Reviews, St. Louis, Mosby, 2005.

TABLE 17-3 Lactation Risk Categories

| RISK CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION | |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | Safest | |

Adapted from Hale T: Medications and Mother’s Milk: A Manual of Lactation Pharmacology, 10 ed. Amarillo, Pharmasoft Publishing, 2002.

Adaptogens

The role of adaptogens in improving stress resistance and response is extensively discussed in Chapter 6. No studies have been conducted on the use of these herbs for PPD; however, they are widely used by herbalists for the treatment of general depression and no adverse effects are expected from their use during lactation. Use during pregnancy is generally not recommended. Women at high risk for developing PPD can begin the use of adaptogens in the days or weeks after birth to improve the ability to handle stress, withstand sleep deprivation, and also to improve nonspecific resistance. Ashwagandha may have anxiolytic activity.53 Schisandra is used to calm the spirit, for insomnia, palpitations, and poor memory. Contradictory information exists on its safety in pregnancy. It is generally contraindicated in pregnancy owing to its potential for increasing uterine contractions. However, no adverse effects on the fetus have been observed with maternal use, and in fact, some studies have demonstrated increased fetal weight and improved birth outcome with use of adaptogens. Although these herbs are considered compatible with lactation, it is best to avoid their use during pregnancy owing to inconclusive evidence of safety.54

Nervine Relaxants, Sedatives, Tonics, and Anxiolytics

St. John’s wort is the most thoroughly studied herb for the treatment of depression. It is the primary medication used for depression in several European countries and it has become a popular alternative to pharmaceutical antidepressant medications in the United States. As of 2002, 34 controlled clinical trials of over 3000 patients have demonstrated the efficacy of this herb for treating mild to moderate depression (see Plant Profiles).57 No studies have evaluated the herbs for either efficacy or safety in the treatment of PPD.50 The herb is not contraindicated for use during pregnancy; however, safety studies are lacking. There is one published case report in which low levels of hyperforin were detected in the breast milk of a woman consuming 300 mg/day; however, no constituents of the herb were detectable in the baby’s plasma and no adverse effects were observed in either.58 Lactation and medication expert Hale states that recent data suggest transfer to milk is minimal and that St. John’s wort appears to be safe for use during lactation.47 Because of its potent ability to induce cytochrome P450 3A4, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme in the liver, St. John’s wort is contraindicated with the use of other drugs, including MAOIs and SSRIs.59

Kava kava is traditionally used to promote a calm, relaxed mood and as a ceremonial and social drink by Pacific Islanders.60 It used extensively in Europe and the United States as a treatment for anxiety and insomnia, both of which are associated with PPD.61 Kava has been shown to improve general relaxation response time.62 Studies have demonstrated kava to be a highly effective treatment for anxiety.63 Kava has been shown to be significantly more effective than placebo in clinical trial participants with moderately severe, nonpsychotic anxiety disorder, perhaps even more effective than benzodiazepines.64 It has been generally well tolerated at recommended doses, although individuals taking higher doses of kava may experience fatigue, unsteadiness, appearance of intoxication, and skin changes.64 As of 2000, however, approximately 60 adverse case reports suggesting a link between kava use and liver failure have led to the governments of at least eight countries removing kava from the general market. The German Commission E contraindicates the use of kava during pregnancy and lactation; however, no specific data on pregnancy and lactation exists. Ethnobotanical information suggests that the herb is avoided to maintain fertility and during pregnancy, but information on use during lactation is not reported.60 Insufficient information on the use of kava during lactation makes it difficult to predict safety. The risk of hepatotoxicity from the herb vs. risks of conventional drugs for anxiety treatment, including addiction and infant sedation or toxicity must be investigated and evaluated.60 However, until then and in light of recent concerns raised about kava and hepatotoxicity, it is prudent to avoid this herb during lactation. The herb is definitely contraindicated during pregnancy because of possible risk.

Motherwort is perhaps the classic historical herb for postpartum depression, anxiety with palpitations, and stress. The name of the herb itself mother wort—a healing herb for mothers—and its botanical name Leonurus cardiaca—heart of a lion—are evocative of its traditional healing uses. Today, the herb finds its way into many gynecologic formulae. It is used as a uterine tonic and antispasmodic, as a bitter to stimulate the liver, as a nervine and sedative, and in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and palpitations, including the latter in the treatment of hyperthyroidism. It is very popular for its perceived ability to modulate irritability and emotional lability. It may possess some hormonal activity, although this has not been thoroughly evaluated. Most of the evidence for this herb remains largely anecdotal.65 It is approved by the German Commission E for nervous cardiac conditions and as an adjuvant for thyroid hyperfunction.52 Motherwort is contraindicated in pregnancy but is safe during lactation.

Blue vervain has been used historically as a galactagogue and to treat nervous exhaustion; however, no studies have been done to confirm its efficacy.52 Limited studies have demonstrated some effects on the endocrine system where it appears to stimulate FSH and LH. It may also have antithyrotropic effects and synergistic effects with prostaglandin E2, although the significance of these effects is unknown beyond possibly contributing to the herb’s traditional use as an emmenagogue.65 The herb is used by herbalists similarly to motherwort for its perceived ability to modulate irritability and emotional lability. It is contraindicated in pregnancy but is safe during lactation.

California poppy is used by herbalists as a mild sedative to promote sleep and reduce nervousness and anxiety in calming but not heavily sedating. It has demonstrated anxiolytic, mild sedative, and hypnotic effects. It should be considered when there is disturbed sleep (see Insomnia) or anxiety (see Anxiety). It was a popular drug in the late 1800s, when it was sold as a pharmaceutical product by Parke-Davis as a soporific (sleep-inducing) and analgesic agent. Extracts of California poppy inhibit catecholamine degradation and epinephrine synthesis. The former activity may be especially responsible for the herb’s sedative and antidepressant activities. Sedative, anxiolytic, and muscle relaxant effects have been observed experimentally in animals injected with California poppy extracts. Two controlled clinical trials demonstrated normalization of sleep without carryover effects when combined with corydalis (Corydalis cava).66

Passion flower is approved by the German Commission for the treatment of nervous restlessness, and recommended by ESCOP for the treatment of tenseness, restlessness, irritability, and difficulty with falling asleep, indications for which herbalists generally prescribe this herb.52,67 Pharmacodynamic studies and a limited number of clinical trials that have been conducted appear to support its empirical uses as an anxiolytic and sedative herb (see Plant Profiles).67 Safety during pregnancy is not established; the herb is compatible with lactation.

Skullcap has been used traditionally as a relaxing nervine to support and calm the nervous system, for nervous exhaustion, excitability, irritability, overwork, sleep disorders, depression, and exhaustion from mental strain.66 There is little pharmacologic or clinical research on this widely used herb, and there has been some controversy in the literature regarding its efficacy. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of healthy subjects by Wolfson and Hoffmann demonstrated noteworthy anxiolytic effects.68 Because of potential of adulteration with the hepatotoxic herb germander (Teucrium chamaedrys) it is best to avoid this herb during pregnancy; notwithstanding this concern, its use is safe during lactation. Obtaining the herb from a reliable source should largely mitigate the concern of adulteration.

FORMULAS FOR POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION

The following examples of formulas for the treatment of various PPD symptoms and can be used both by nursing and non-nursing mothers. Formula can be modified for the individual needs of specific patients as required. Additionally, drinking herbal tea is a relaxing ritual for new mothers—a few minutes to sip a cup of hot tea can not only be medicinal but a needed moment for quiet and calm. A cup of hot tea can be taken while nursing or holding the baby, even if mom can’t get a moment to herself. Mother’s milk tea is a relaxing and delicious favorite of many women.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

| 1 oz dried chamomile flowers | (Matricaria recutita) |

| 1 oz dried catnip | (Nepeta cataria) |

| ¼ oz fennel seeds | (Foeniculum vulgare) |

| ⅛ dried lavender blossoms | (Lavandula officinalis) |

| Blue vervain | (Verbena officinalis) | 25 mL |

| Motherwort | (Leonurus cardiaca) | 25 mL |

| Skullcap | (Scutellaria lateriflora) | 25 mL |

| Nettles | (Urtica dioica) | 25 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

| Ginseng | (Panax ginseng) | 10 mL |

| St. John’s wort | (Hypericum perforatum) | 25 mL |

| Licorice | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | 15 mL |

| Ashwagandha | (Withania somnifera) | 30 mL |

| Blue vervain | (Verbena officinalis) | 20 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

help erratic shifts in blood sugar, energy levels, and thus emotions.

Essential Fatty Acids

Essential fatty acids are critically important to a healthy functioning nervous system.69,70 Evidence indicates an association between omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and depression.71,72 The relationship between omega-3 PUFAs and depression is biologically plausible and is consistent across study designs, study groups, and diverse populations, which increases suggesting a causal relationship.73 Four of six double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in depression, have reported therapeutic benefit from omega-3 fatty acids in either the primary or secondary statistical analysis, particularly when EPA is added on to existing psychotropic medication. The evidence to date supports the adjunctive use of omega-3 fatty acids in the management of treatment unresponsive depression.74 Several studies suggest that docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) fatty acid supplements given to nursing mothers may reduce the incidence of postpartum depression and also improve early infant development. High EFA intake and high fish consumption have been inversely correlated with incidence of depression.75,76 In fact, higher the intake of DHA by nursing mothers is related to a lower reported incidence of postpartum depression, with women in Singapore consuming 81 lb per year per woman and reporting 0.5% incidence of PPD compared to women in South Africa

When anxiety is the predominant symptom accompanying depression.

| Kava kava | (Piper methysticum) | 20 mL |

| Ashwagandha | (Withania somnifera) | 20 mL |

| St. John’s wort | (Hypericum perforatum) | 20 mL |

| Motherwort | (Leonurus cardiaca) | 15 mL |

| Schisandra | (Schisandra chinensis) | 15 mL |

| Licorice | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

For Depression with Mild Sleep Difficulty

| Skullcap | (Scutellaria lateriflora) | 20 mL |

| Passionflower | (Passiflora incarnata) | 30 mL |

| Chamomile | (Matricaria recutita) | 20 mL |

| Linden | (Tilea spp.) | 20 mL |

| Lavender | (Lavandula officinalis) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

who consume on average 8.6 lb of fish per year per woman, and reporting an incidence of 24.5% PPD per year. Women in the use fall about halfway between these extremes in both fish consumption and PPD incidence.72 The DHA content of mother’s milk in the United States is among the lowest in the world—about 40 to 50 mg in US women, 200 mg in European women, and about 600 mg in Japanese women. Women who want to increase their DHA levels can take dietary supplements or eat more tuna, salmon, and other foods rich in DHA. To avoid mercury contamination, however, current guidelines suggest limiting fish to 12 oz of cooked fish per week during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and avoiding shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish. The dose of omega-3 PUFAs required for supplementation to prevent or treat postpartum depression is still not entirely clear. The recommended daily dose of 200 mg DHA has not been consistently sufficient in trials, whereas 1 g/day of EPA has shown more consistent benefit, and has been demonstrated to be superior in reliving symptoms such as delusion, hallucinations, and bizarre behavior in major depression. It is recommended that women supplement with 1 to 3 g/day of a fish oil supplement containing both DHA and EPA.57 Twenty fish oil supplements tested for mercury levels by an independent lab were found to be free of detectable levels of mercury.57 Many reputable fish oil companies will offer product information that address this concern for professionals and consumers.

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Massage for Mom and Baby

Therapeutic massage for the mother can provide an important opportunity for stress release and time to self-nourish on a regular basis, and can impart of feeling of being care for.50 A study by Field et al. found that depressed teenage mothers receiving massage (10 sessions reported) experienced decreased depression and anxiety, had statistically significant behavior changes, and decreased salivary cortisol levels after a session.77 Infant massage, which mothers can easily be trained to do, may also have benefits not only for the infant of the depressed mother via insuring contact and bonding that may become neglected with PPD, but also for the mother. Infants who receive massage regularly may sleep better and be less fussy, reducing potential stress, anxiety, and depression triggers for the mother, but also the act of giving infant massage can improve the mother’s sense of connection and attachment to her baby while helping her to feel confident handling the baby and validated as a “good mother” for the effort she is making. A study by Onozawa et al. found that depression scores were reduced for both mothers with PPD and their infants as a result of regularly attending infant massage classes, and mother–infant interactions were improved.78

Aromatherapy

Scent can uplift the spirit, and its connection to memory and emotion has been well-documented. Several scents have been traditionally used to relieve depression; most notable among these is lavender oil. Although there is not data on the use of herbs to treat PPD, some evidence suggests the positive effects of lavender oil for the treatment of general depression.50 The dilute oil may be used in a massage oil, or may be diffused in the room with an oil diffuser, sprinkled onto a pillow, or added to a bath. Care should be taken when oils are applied to the skin that they be dilute enough not to cause irritation. Usually several drops of essential oil to several tablespoons of carrier oil (e.g., almond oil) and 3 to 7 drops of undiluted essential oil added to a full bath are adequate.

CASE HISTORY: POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION

Treatment Summary for Postpartum Depression

| Motherwort | (Leonurus cardiaca) | 25 mL |

| Eleuthero | (Eleutherococcus senticosus) | 25 mL |

| Blue vervain | (Verbena officinalis) | 20 mL |

| Passion flower | (Passiflora incarnata) | 20 mL |

| Lavender | (Lavandula officinalis) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

POSTPARTUM PERINEAL HEALING

Episiotomy is one of the most commonly performed procedures in obstetrics. In 2000, approximately 33% of women giving birth vaginally had an episiotomy. Historically, the purpose of this procedure was to facilitate completion of the second stage of labor to improve both maternal and neonatal outcomes. Maternal benefits were thought to include a reduced risk of perineal trauma, subsequent pelvic floor dysfunction and prolapse, urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and sexual dysfunction. Potential benefits to the fetus were thought to include a shortened second stage of labor resulting from more rapid spontaneous delivery or from instrumented vaginal delivery. Despite limited data, this procedure became virtually routine resulting in an underestimation of the potential adverse consequences of episiotomy, including extension to a third- or fourth-degree tear, anal sphincter dysfunction, and dyspareunia.79

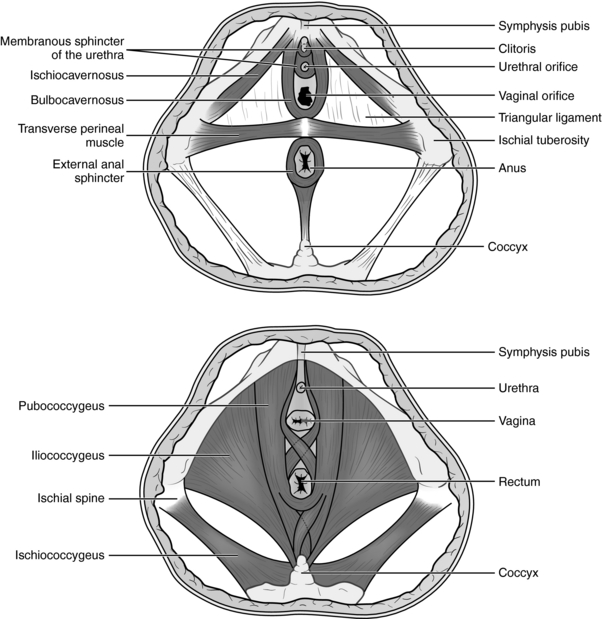

The perineum is a muscular body at the inferior boundary of the pelvis, bordered superiorly by the muscles of the levator ani, and inferiorly by fascia. It is bordered by the vaginal introitus anteriorly and the rectal sphincter muscles and rectum posteriorly (Fig. 17-1). Because of the mechanical stresses of the baby’s presenting part, particularly the head, on the perineum during birth, the perineum is subject to tearing during the second stage of labor (pushing). In the 1920s, episiotomy, the surgical cutting of the perineum, became a routine procedure for second state labor, predicated on the belief that the normal mechanical stresses of birth posed the risk of considerable overstretching of the pelvic floor muscles, predisposing women to long-term or permanent damage and risk of pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence. The final stitch placed in a repair job has often been referred to as the “husband’s knot,” and it was not uncommon for an obstetrician to inform the new mother or her partner that she would be “better than new” after the repair! Medically, it is considered easier to repair a smooth surgical incision than a possibly jagged laceration that occurs naturally.

Figure 17-1 The female perineum and pelvic floor muscles.

Stillerman E: Prenatal Massage: A Textbook of Pregnancy, Labor, and Postpartum Bodywork, St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.

By the 1980s, episiotomy was being performed in rates in excess of 60% of all vaginal births.80 More recently, emerging evidence of the lack of benefit of episiotomy, and associated risks, along with increased demand from maternal consumers that this procedure be avoided, has led to a significant decline in episiotomy rates to as low as 30% to 35% of all vaginal deliveries (against a backdrop of 27.5% of hospital deliveries now occurring by cesarean section).81 As stated in the introductory quote, limited data supported the efficacy or safety of this procedure in preventing maternal damage as a result of normal vaginal childbirth, and the procedure itself has resulted in deleterious consequences for innumerable women, with soreness, itching, thickening, and scarring of the perineal tissue leading to lack of pliability and dyspareunia as common complaints.

Ironically, not only does routine episiotomy not reduce perineal trauma in most instances, episiotomy incisions frequently extend from first degree lacerations to third and fours degree lacerations, involving the pelvic floor musculature and rectum, and anal sphincter, with the emergence of the baby over the perineum. In fact, episiotomy is the overriding factor in the length of perineal tearing.82 Bleeding is a common complication, and infection and permanent sphincter dysfunction not rare. Infection has led to anovaginal fistula, and rarely, infection has resulted in maternal mortality.79

It has a common obstetric myth that episiotomy is necessary in cases where expediting delivery in the second stage of labor is warranted for the safety of the fetus, or where the likelihood of spontaneous laceration to the mother seems high. Examples of these indications include ominous fetal heart rate, operative vaginal delivery such as forceps, shoulder dystocia, or a “short” perineal body. However, several trials suggest evidence supporting these claims is lacking. Two recent trials also failed to show evidence that episiotomy improved neonatal outcome, provided better protection of the perineum, or facilitated operative vaginal delivery.83,84 Current evidence-based medicine does not support liberal or routine use of episiotomy. Although there is a role for episiotomy for a limited number maternal or fetal indications, such as avoiding severe maternal lacerations or facilitating or expediting emergency deliveries, a recent systematic evidence review found that prophylactic use of episiotomy does not appear to result in maternal or fetal benefit.81 In fact, it appears to confer more harm than benefit.80 Nonetheless, of those women who prefer elective caesarean section rather than vaginal delivery, 80% do so because of the fear of perineal damages.85

PREVENTION OF PERINEAL TEARS

Perineal tearing, even in the absence of episiotomy, is a common occurrence accompanying vaginal childbirth. Tears are generally first- or second-degree tears, with third- or fourth-degree tears involving the musculature and rectum more likely to occur as a result of a tear that extends an episiotomy. Repair of natural tearing, as well as episiotomy, can lead to noticeable and prolonged discomfort and mild to moderate dysfunction for many women, depending upon the extent of the damage and the quality of the repair. A systematic review of the English language literature was conducted in 1998 to describe the current state of knowledge on reduction of genital tract trauma. A total of 77 papers and chapters were identified and placed into four categories after critical review: 25 randomized trials, four meta-analyses, four prospective studies, 36 retrospective studies, and eight descriptions of practice from textbooks.86 The case for restricting episiotomy is conclusive—what remains uncertain is which techniques for preventing tears are effective. Midwives have consistently demonstrated reduced rates of perineal damage, with lower episiotomy rates, lower tear rates, and less damage to the perineum when either of the above occurs.87,88 Techniques commonly employed include prenatal perineal massage, intranatal perineal massage, and application of hot compresses to the perineum during second state, as well as use of alternative positions to the lithotomy position, including standing, squatting, semirecumbent, and lateral positions. The contribution of maternal characteristics and attitudes to intact perineum has not been investigated to date.86 Achieving an intact perineum, whether through avoidance of tearing or use of episiotomy can have significant effects on a woman’s long-term health after birth. For example, a study by Signorello et al. reported that at 6 months postpartum about one-fourth of all primiparous women reported lessened sexual sensation, worsened sexual satisfaction, and less ability to achieve orgasm, as compared with these parameters before they gave birth. At 3 and 6 months postpartum, 41% and 22%, respectively, reported dyspareunia. Relative to women with an intact perineum, women with second-degree perineal trauma were 80% more likely and those with third- or fourth-degree perineal trauma were 270% more likely to report dyspareunia at 3 months postpartum.89

Prenatal Perineal Massage

Three trials (2434 women) comparing digital perineal massage with control were included in a review of antenatal massage and birth outcome by the Cochrane Collaboration. Antenatal perineal massage was associated with an overall reduction in the incidence of trauma requiring suturing. This reduction was statistically significant for women without previous vaginal birth only. Women who practiced perineal massage were less likely to have an episiotomy. Again, this reduction was statistically significant for women without previous vaginal birth only. No differences were seen in the incidence of first or second degree perineal tears or third- or fourth-degree perineal trauma. Only women who have previously birthed vaginally reported a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of pain at 3 months postpartum. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of instrumental deliveries, sexual satisfaction, or incontinence of urine, feces, or flatus for any women who practiced perineal massage compared with those who did not massage. The authors concluded that antenatal perineal massage reduces the likelihood of perineal trauma (mainly episiotomies) and the reporting of ongoing perineal pain and is generally well accepted by women. As such, women should be made aware of the likely benefit of perineal massage and provided with information on how to massage.90 Another study evaluating the associations between perineal lacerations and 13 variables associated with the incidence of perineal lacerations concluded that perineal massage was beneficial not only to primiparous women but also to multipara who had episiotomies with their previous births.91 Additional studies have demonstrated that women find prenatal perineal massage and acceptable practice.92

Birth Position, Practitioner Type, and Prevention of Perineal Trauma

In a study evaluating birth position and midwife versus obstetric outcomes in relation to intact perineum at birth, retrospective data from 2891 normal vaginal births were analyzed using multiple regression. A statistically significant association was found between birth position and perineal outcome, with a lateral position associated with the highest rate of intact perineum (intact rate 66.6%) and squatting for primiparas associated with the least favorable perineal outcome (intact rate 42%). Semirecumbent, standing, and “all-fours” positions led to outcomes of 36.3%, 42.7%, and 44.4%, respectively. The obstetrician group had an episiotomy rate greater than five times that of midwives, and generated tears requiring suturing 42.1% of the time, an average of 5 to 7 percentage points higher than midwives. In midwife supported births, an intact perineum was achieved 56% to 61% of the time, compared with 31.9% for obstetricians.87 Additional studies have demonstrated improved perineal outcomes with birth in an upright position.93 Midwives use a variety of techniques to support the perineum during birth. This study was an attempt to begin to understand which of these factors contribute to improved outcomes, and to what extent. However, it should be remembered that it may be the gestalt of factors together that is ultimately responsible for improved perineal outcome at birth.

Intranatal Perineal Massage and/or Hot Compresses during Birth

In one clinical trial done to evaluate these methods, neither intranatal perineal massage nor hot compresses during second stage of labor reduced the incidence of spontaneous perineal tearing as independent techniques. However, as these measures are not harmful and they provide comfort to many women, their use should not be excluded but should be based on whether they provide maternal comfort.80

“Easing the Baby Out” and “No Touching” until Crowning of the Head

Techniques not used by the medical community, but widely reported by midwives include easing the baby out gently rather than bearing down to push, and not touching the perineum until the baby’s head is crowning.94 The former practice encourages the mother to breathe with urges to push rather than using a Valsalva method, and, based on observation, appears to minimize pressure against the perineum as the head begins to emerge, and allows a slow emergence of the head, which may optimize perineal stretching over a fast delivery with the added force of maternal pushing behind it. Many midwives practice “no touching” rather than aggressive second-stage intranatal perineal massage or the practice of “ironing” the perineum, to thin and stretch it, as is commonly practiced in obstetrics. These techniques have not been studied systematically but may contribute to the improved perineal outcomes associated with midwifery care.

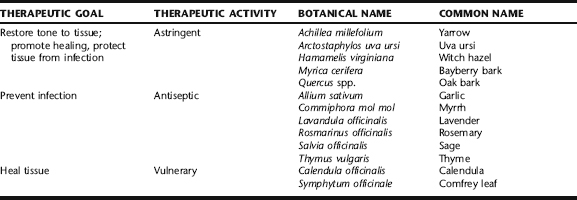

BOTANICAL TREATMENT FOR PERINEAL HEALING

For women who have experienced perineal trauma with birth, perineal healing is a concern (Table 17-4). Whether as a result of nonsurgical laceration or routine or medically necessitated episiotomy, if a surgical repair was done (stitches), postpartum perineal discomfort can be significant, with itching, soreness, tenderness, and even pain. Discomfort can sometimes persist for months after childbirth, interfering with normal activities, exercise, and sex. For some women, this has serious implications in their work life and marriage/sexual relationships. Severe perineal trauma at birth, even in the absence of episiotomy, can also lead to delayed return of sexual activity and perineal discomfort.

Astringent herbs such as yarrow, witch hazel, and white oak bark, vulnerary herbs such as calendula and comfrey, antiseptic herbs such as sage and myrrh, and a mild topical analgesic such as lavender can be made into strong decoctions, which can be applied to the perineum via a peri-wash or sitz bath. Alternatively, tinctures of these herbs can be diluted in water and similarly applied. These herbs can accelerate healing from perineal tears and episiotomy, reduce swelling and bruising, and alleviate pain and soreness. Peri-rinses can be used after each use of the toilet, and sitz baths can be taken one to two times daily as needed. These techniques are repeated up to 5 days postnatally. Sample recipes that are popular for use among midwives are described below. See Chapter 3 for instructions on preparing herbal baths, sitz baths, and peri-rinses. Studies on the activities of many of these herbs are found in specific Plant Profiles. With the exception of lavender, which has been studied minimally for this purpose, few studies have been conducted on the use of herbs specifically for postnatal perineal

A blend of beautiful and fragrant blossoms that is soothing, healing, and antiseptic.

| Comfrey leaves | (Symphytum officinalis) | 2 oz |

| Calendula flowers | (Calendula officinalis) | 1 oz |

| Lavender flowers | (Lavandula officinalis) | 1 oz |

| Sage leaf | (Salvia officinalis) | ½ oz |

| Myrrh powder | (Commiphora mol mol) | ½ oz |

| Total: 5 oz | ||

| Comfrey leaf | (Symphytum officinalis) | 1 oz |

| Yarrow blossoms | (Achillea millefolium) | 1 oz |

| Sage leaf | (Salvia officinalis) | 1 oz |

| Rosemary leaf | (Rosmarinus officinalis) | 1 oz |

| Total: 4 oz | ||

healing. Anecdotally, women report these to be soothing, and look forward to repeating the baths and rinses. These applications are also effective in reducing hemorrhoids postnatally, and for this purpose, may additionally be used directly on the hemorrhoids in the form of

Astringent and Antiseptic Tincture

Mix all tinctures and add ½ fl oz of the mix to 4 oz of warm water in a peri-bottle.

| Witch hazel bark | (Hamamelis virginiana) | ½ fl oz |

| Calendula | (Calendula officinalis) | ½ fl oz |

| Lavender | (Lavandula officinalis) | ½ fl oz |

| Myrrh tincture | (Myrica cerifera) | ½ fl oz |

| Total: 2 fl oz | ||

compresses of the teas. When using compresses, omit the garlic, which is too irritating to be applied directly, and omit the sea salt, which is unnecessary.

Lavender

Lavender herb and oil are traditionally used by herbalists for their antiseptic and mild analgesic properties when applied topically. It is commonly recommended by midwives and herbalists as an ingredient in postpartum sitz baths. Researchers at the Hinchingbrooke Hospital, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, undertook a blind randomized clinical trial using a total of 635 postnatal women to test these claims. The women were divided into three groups; the first group was given pure lavender oil, the second group being given synthetic lavender oil, and the third group were given an inert substance as bath additives to be used daily for 10 days following normal childbirth. Analysis of the total daily discomfort scores revealed no statistically significant difference between the three groups. However, on closer inspection, the outcomes showed that those women using lavender oil recorded lower mean discomfort scores on the third and fifth days than the two control groups, which is a time when the mother usually finds herself discharged home and perineal discomfort is high.95