Chapter 57 The postoperative management of OSA patients after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Inpatient or outpatient?

1 INTRODUCTION

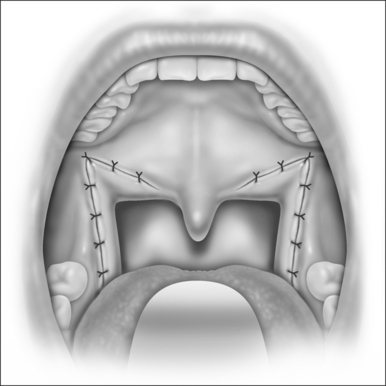

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition that is estimated to affect up to 4% of the adult population.1 The OSA syndrome can be defined as the periodic cessation of airflow during sleep. The most common symptoms of this syndrome include loud snoring, daytime sleepiness and cognitive impairment. A variety of surgical procedures, which include tracheotomy, nasal surgery, and uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty (UPPP) with or without tonsillectomy, may be performed to alleviate symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life.

Out of the available procedures, UPPP is the most common surgery performed for adult patients with OSA. It was originally introduced by Fujita in 1981.2 Despite the frequency of this procedure, the appropriate level of postoperative monitoring for complications has become a controversial issue. Initially all UPPP patients were monitored postoperatively in the intensive care unit. It is the opinion of the authors of this chapter that there is no unique danger to uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea that would require such intensive postoperative observation. Nonetheless, otolaryngology textbooks typically recommend close observation in the recovery area and subsequent transfer to the intensive care unit for the first 24 hours post UPPP.3 Currently, some surgeons still advocate a 24-hour observation period as a routine part of postoperative management.

On the other hand, others may prefer close monitoring but do not recommend it as a routine practice. Instead they base the need for extended observation on the severity of a patient’s OSA, the extent of the operation and the presence of pre-existing medical conditions. In fact, many recent reports have concluded that routine postoperative ICU monitoring is not necessary, stating that intensive care or step-down unit monitoring should not be required for most patients after upper airway surgery for OSA since most complications occur within a few hours of the procedure.4–6

While it is clear that a variety of factors may influence a surgeon’s decision to prolong postoperative care, studies have shown that most overnight admissions for UPPP are uneventful and in most cases, same-day discharge is advisable.7 Based on this fact, this chapter seeks to clarify and outline appropriate postoperative management strategies of OSA patients undergoing UPPP.

2 POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Inherently, there is no greater risk of postoperative complications with UPPP surgery than with tonsillectomy, which is commonly conducted on an outpatient basis. While complications do occur after UPPP, researchers have shown that they are most common in the immediate, postoperative care period and overnight stay may not be a necessary part of postoperative management of OSA patients undergoing UPPP.8

Although the overall incidence of serious postoperative complications after UPPP is low,9 it is important to review which complications may occur in order to understand how they affect a surgeon’s approach to managing patients. In the case of UPPP, complications may be categorized as either early or late events. Early complications can be defined as those that occur either intraoperatively, immediately postoperatively or in the recovery room. Late complications may be observed over the course of the inpatient stay. The most commonly reported early postoperative complications are either respiratory in origin or involve bleeding from the surgical site.8 Other early complications include arrhythmia, hypertension, pain, dehydration and poor oral intake. All of these possibilities should be addressed before determining the most appropriate postoperative management plan for UPPP patients.

2.1 AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Although airway obstruction may be considered a common postoperative complication after UPPP, the actual incidence of such an event is quite low. Additionally, there has been a change in the number of serious respiratory complications reported over time, with more recent studies reporting lower rates. For example, in 1989 Esclamado et al.10conducted a retrospective chart review of 135 patients surgically treated for OSA and found the incidence of respiratory complications to be 10.3%. Half of these complications were airway obstructions that occurred at extubation, and half were due to failed intubation. It is important in a discussion of postoperative management to note that the onset of all respiratory events occurred in the early phase. That is, all respiratory complications occurred during or immediately after intubation. A review in 1994 by Haavisto and Suonpaa11 of 101 patients undergoing UPPP for OSA showed an incidence of airway complications of 11%. Again all cases occurred in the early phase.

In a 1998 review of 109 patients undergoing UPPP for OSA, Terris et al. reported a 5.5% incidence or early respiratory complications.6 This rate included one case of airway compromise, and the patient required naloxone, oxygen and suctioning of his airway. This single episode of airway obstruction occurred only 15 minutes after the patient was transferred out of the operating room.

An additional 1998 study by Mickelson and Hakim of 347 patients undergoing UPPP for OSA reported only five patients who had experienced airway-related complications, or 1.4% of all patients.5 Three of the five suffered shortness of breath either at extubation or immediately after in the recovery room. Two of the five patients experienced complications in the surgical ward. These included one case of pulmonary edema and one case of shortness of breath of unclear origin. No actual cases of airway obstructions were reported.

Spiegel and Raval reviewed 117 patients in 2005 for complications associated with UPPP.8 Ten patients were discharged the same day as the surgery. The remainder of the patients experienced a 4.3% incidence rate of respiratory complications. While most cases were due to oxygen desaturation, two patients developed airway obstruction from presumed laryngospasm at the time of extubation. Both of these patients developed postobstructive pulmonary edema within minutes of the obstruction.

2.2 OXYGEN DESATURATION

Oxygen desaturation is also often cited as a common complication in OSA patients undergoing UPPP. A value of less than 85–93% is typically considered significant desaturation. In the past, some surgeons have advocated postoperative ICU monitoring for fear of serious desaturation events. However, such monitoring may not be reasonable since most desaturations occur in the early phase of recovery. Additionally, more mild nocturnal desaturations may continue for weeks, since UPPP does not correct OSA immediately.12

The fact that most occurrences of desaturations happen relatively early in the recovery process further supports same-day patient discharge for the majority of patients. For example, in a 2006 study by Hathaway and Johnson of 110 patients undergoing UPPP, desaturations in three patients all occurred in the recovery room.7 In the review by Spiegel and Raval, three desaturations below 90% were reported.8 The first desaturation occurred in the recovery room, the second on the first postoperative night and the third on the first postoperative day. The third patient likely desaturated on the first postoperative day because he was given narcotic patient-controlled analgesia (morphine) for pain, and narcotic analgesia tends to impede respiratory function.

Advocates of extended postoperative stays after UPPP also claim the need for post-surgical oxygen supplementation on the floor as an important argument for hospitalization. However, there is some evidence that there may not be a direct relationship between oxygen supplementation and lower desaturation rates. For example, Riley et al.13 found no significant difference in the postoperative low oxyhemoglobin saturation (LSAT) between patients receiving continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and the non-CPAP group.

A patient’s preoperative Respiratory Distress Index (RDI) may also be a poor predictor of whether or not they may desaturate, as was the case in the review by Hathaway and Johnson.7 While two of the admitted patients had RDIs over 50 (indicating severe OSA) one patient had an RDI of 22 and still desaturated. Desaturations occurred in the recovery room, and all patients were admitted into the hospital, but none required the ICU. The authors concluded that preoperative polysomnography data such as the RDI may not predict which patients will experience desaturation in the early postoperative period.

Overall, research shows that desaturation, particularly nocturnal desaturation, is a very common complication of UPPP surgery for OSA. In fact, it should be considered more of an expectation than a complication. Giving oxygen postoperatively may or may not make a difference, so admitting all UPPP patients in order to give them oxygen would not be reasonable. Also, preoperative sleep indices may not be an accurate indicator for identifying patients who may desaturate, so it would not be practical to hospitalize all patients due to fear of this complication. The most likely scenario is that if a serious desaturation occurs, it would be in the early phase of recovery, at which point the patient should be admitted to the hospital. Otherwise, minor nocturnal desaturations are to be expected since it may take a few weeks to note improvement in a patient’s OSA.

2.3 BLEEDING

Bleeding, particularly from the surgical site, is another frequently noted complication of UPPP. The onset of bleeding tends to be biphasic with cases either occurring immediately after surgery or more than 24 hours post operation.8

For example, a Haavisto and Suonpaa review of 101 in 1994 had an incidence rate of hemorrhage of 14% or 14 totalcases.11 Out of the 14 cases, nine required surgical management such as electrocautery and ligation while five were managed with conservative treatment or suctioning. All butone of the hemorrhages that required electrocautery occurredwithin 5 hours of the initial surgery during the early phase of recovery. Three cases occurred much later, at 24 hours or more post procedure. One patient reportedly experienced asystole and died.

In a paper by Esclamado et al., hemorrhage that required return to the OR occurred in 2.2% of patients immediately post operation.10 Mickelson and Hakim reported a 1.4% incidence of bleeding, or a total of five cases.6 This included two episodes of epistaxis, one of tracheostomy bleeding, and a third of bleeding from the patient’s tonsils. These four cases occurred in the early phase of recovery. However, one patient began to bleed from his tonsillectomy site while out on the surgical ward and required a return to the ICU.

Spiegel’s study also illustrated the biphasic nature of bleeding events and reported seven cases of hemorrhage with time of onset ranging between 5 and 14 days postoperatively.8 No cases of bleeding were reported during the hospital stay.

2.4 CARDIAC COMPLICATIONS

Hypertension, arrhythmia, angina and miscellaneous other cardiac complications are also observed after UPPP, but tend to be relatively rare. Significant hypertension frequently occurs intraoperatively or immediately after surgery. In the Terris et al. study, seven of 125 patients were described as having mild hypertension (systolic pressure greater than 190 mm Hg and diastolic over 100 mm Hg) and did not require intravenous anti-hypertensive drugs or ICU monitoring.6 Six additional patients experienced severe hypertension and required intravenous treatment, but in all of the cases hypertension manifested in the first 2 postoperative hours.

Hypertension requiring intravenous narcotics was also noted in three cases by Spiegel and Raval.8 All three cases occurred in the recovery area, and two of the three patients had a medical history of hypertension. Riley et al.13 reported the highest rate of postoperative hypertension that required intravenous medication at 70.5%. Such elevated rates may be due to the fact that OSA patients tend to experience a higher incidence of postoperative hypertension because they have a greater prevalence of hypertension prior to surgery. Comorbid factors such as elevated Body Mass Index (BMI) and age may account for some of the association, but OSA itself probably presents an independent risk factor as well.6 Since most cases of postoperative hypertension occur in the early phase of recovery and can be controlled with intravenous narcotics, hypertension alone should not constitute a reason for prolonged inpatient visits of ICU monitoring.

While hypertension is the most common cardiac complication after UPPP, cases of arrhythmia and angina have also been reported. In the review by Riley et al., four out of 182 patients (1.9%) had a postoperative arrhythmia that required treatment despite a negative medical history and work-up.13 All reported arrhythmias were new-onset atrial fibrillations. One patient had unstable angina.

Terris et al. also noted one arrhythmia, but the patient had a prior history of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs).6 Haavisto and Suonpaa also reported one case of arrhythmia.12 A review of 1004 patients by Spiegel and Raval,8 which included the studies mentioned above, found an average rate of arrhythmia of 0.8%, and 0.2% for angina. Clearly, these complications are very rare and monitoring during the early phase of recovery should be sufficient in detecting the vast majority of such adverse cardiac events.

2.5 PULMONARY EDEMA

Postobstructive pulmonary edema (POPE) is a much feared complication for OSA patients undergoing UPPP and is often cited as a justification for admission. One theory is that POPE, also known as negative pressure pulmonary edema, is a non-cardiogenic pathologic process in which the generation of markedly negative intrathoracic pressures that are created by forced inspiration againsta closed glottis cause a transudation of fluid into the pulmonary interstitium.14 Typically, POPE has a benign and rapidly resolving clinical course, assuming it is recognized and treated in a prompt manner.

However, studies reveal that POPE can also result in significant morbidity, with mortality rates ranging from 11% to 40%, so clearly it is of concern to physicians.14 Why POPE appears in some individuals and not others is unclear. Literature has shown that POPE is usually triggered by laryngospasm during extubation. Again, this serious complication is identified in the immediate postoperative period (early) and a prolonged period of postoperative monitoring would not seem indicated for all patients. In a study by Goldenberg et al.,14 all six reviewed cases of POPE occurred within 60 minutes after the onset or relief of obstruction.

Also, it is important to note that the incidence of POPE is quite low. In a review of 1004 OSA patients undergoing UPPP, only three cases of POPE were reported.8 The risk of POPE can be reduced even further by using a bite lock to prevent accidental compression of the endotracheal tube. When POPE does occur, it usually manifests in the immediate part of recovery, typically at the time of extubation, so overnight monitoring would not decrease its incidence. The use of perioperative corticosteroids may help decrease airway edema,6 but the most important preventive measure possible is immediate recognition and treatment of the problem in the rare circumstances that it does occur.

2.6 PAIN AND DEHYDRATION

Hathaway and Johnson reported on 90 out of 110 UPPP procedures on an outpatient basis.7 Of the 20 patients admitted for overnight stay, eight patients were admitted due to limited oral intake and three for nausea. Five patients had a prolonged stay despite having no specific complications. The same was noted by Spiegel and Raval8 – several patients had a prolonged stay due to inadequate pain control and poor oral intake.

3 CONCLUSION

Polysomnogram measurements such as the RDI do not appear to be a valid way to determine who will need to be admitted for overnight stay. Thus, routine admission based on such indices is not recommended. Because multiple surgeries may be associated with a greater number of complications, particularly the combination of nasal surgery and UPPP,5,7 it is advisable to monitor patients who are undergoing multiple procedures more closely. For example, procedures to reduce the tongue base are particularly worrisome with regard to possible postoperative complications.

With proper monitoring, a 2–3 hour observation period after UPPP should be sufficient for detecting serious postoperative complications. As reviewed in this chapter, most serious complications, such as airway obstruction, desaturation and POPE, occur immediately after surgery during the early phase of recovery. Other complications, such as bleeding, occur in a biphasic pattern, and take place either early on in, or much later than the typical postoperative monitoring period. With careful monitoring in the early phase of recovery, outpatient surgery for OSA patients undergoing UPPP should become routine.

1. Bresnitz EA, Goldberg R, Kosinski RM. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16:210-227.

2. Fujita S, Conway WA, Zorick, et al. Surgical corrections of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-924.

3. Walker RP. Snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. In: Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH, Healy GB, et al, editors. Head and Neck Surgery: Otolaryngology. 3rd edn. Philadelphia:: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001:539.

4. Gessler EM, Bondy PC. Respiratory complications following tonsillectomy/UPPP: is step-down monitoring necessary? Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82:628-632.

5. Mickelson SA, Hakim I. Is postoperative intensive care monitoring necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:352-356.

6. Terris DJ, Fincher EF, Hanasono MM, et al. Conservation of resources: indications for intensive care monitoring after upper airway surgery on patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:184-788.

7. Hathaway B, Johnson JT. Safety of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty as outpatient surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:542-544.

8. Spiegel JH, Raval TH. Overnight stay is not always necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:167-171.

9. Kezirian EJ, Weaver EM, Yueh B, et al. Incidence of serious complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:450-453.

10. Esclamado RM, Glenn MG, McCulloch TM, et al. Perioperative complications and risk factors in the surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1125-1129.

11. Haavisto L, Suonpaa J. Complications of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Clin Otolaryngol. 1994;19:243-247.

12. Burgess LP, Derderian SS, Morin GV, et al. Postoperative risk following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:81-86.

13. Riley RW, Pewell NB, Guilleminault C, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea surgery: risk management and complications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:648-652.

14. Goldenberg JD, Portugal LG, Wenig BL, et al. Negative pressure pulmonary edema in the otolaryngology patient. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:62-66.