Chapter 1 The Physiatric History and Physical Examination

The physiatric history and physical examination (H&P) serves several purposes. It is the data platform from which a treatment plan is developed. It also serves as a written record that communicates to other rehabilitation and nonrehabilitation health care professionals. Finally, the H&P provides the basis for physician billing16 and serves as a medicolegal document. Physician documentation has become the critical component in inpatient rehabilitation reimbursement under prospective payment, as well as proof for continued coverage by private insurers. The scope of the physiatric H&P varies enormously depending on the setting, from the focused assessment of an isolated knee injury in an outpatient setting, to the comprehensive evaluation of a patient with traumatic brain or spinal cord injury admitted for inpatient rehabilitation. An initial evaluation is almost always more detailed and comprehensive than subsequent or follow-up evaluations. An exception would be when a patient is seen for a follow-up visit with substantial new signs or symptoms. Physicians in training tend to overassess, but with time the experienced physiatrist develops an intuition for how much detail is needed for each patient given a particular presentation and setting.

The physiatric H&P resembles the traditional format taught in medical school but with an additional emphasis on history, signs, and symptoms that affect function (performance). The physiatric H&P also identifies those systems not affected that might be used for compensation.22 Familiarity with the 1980 and 1997 World Health Organization classifications is invaluable in understanding the philosophic framework for viewing the evaluation of persons with physical and cognitive disabilities (Table 1-1).76,77 Identifying and treating the primary impairments to maximize performance becomes the primary thrust of physiatric evaluation and treatment.

Table 1-1 World Health Organization Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1980 | |

| Impairment | Any loss or abnormality of psychologic, physiologic, or anatomic structure or function |

| Disability | Any restriction or lack resulting from an impairment of the ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being |

| Handicap | A disadvantage for a given individual, resulting from an impairment or a disability, that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal for that individual |

| 1997 | |

| Impairment | Any loss or abnormality of body structure or of a physiologic or psychologic function (essentially unchanged from the 1980 definition) |

| Activity | The nature and extent of functioning at the level of the person |

| Participation | The nature and extent of a person’s involvement in life situations in relationship to impairments, activities, health conditions, and contextual factors |

From World Health Organization 198076 and 1997,77 with permission of the World Health Organization.

The exact structure of the physiatric assessment is determined in part by personal preference, training background, and institutional requirements (physician billing compliance expectations, forms committees, and regulatory oversight). The use of templates can be invaluable in maximizing the thoroughness of data collection and minimizing documentation time. Pertinent radiologic and laboratory findings should be clearly documented. The essential elements of the physiatric H&P are summarized in Table 1-2. Assessment of some or all of these elements is required for a complete understanding of the patient’s state of health and the illness for which he or she is being seen. These elements also form the basis for a treatment plan.

Table 1-2 Essential Elements of the Physiatric History and Physical Examination

| Component | Examples |

|---|---|

| Chief complaint | |

| History of present illness | Exploring location, onset, quality, context, severity, duration, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms |

| Functional history | Mobility: Bed mobility, transfers, wheelchair mobility, ambulation, driving, and devices required Activities of daily living: Bathing, toileting, dressing, eating, hygiene and grooming, etc. Instrumental activities of daily living: Meal preparation, laundry, telephone use, home maintenance, pet care, etc. Cognition Communication |

| Past medical and surgical history | Specific conditions: Cardiopulmonary, musculoskeletal, neurologic, and rheumatologic Medications |

| Social history | Home environment and living circumstances, family and friends support system, substance abuse, sexual history, vocational activities, finances, recreational activities, psychosocial history (mood disorders), spirituality, and litigation |

| Family history | |

| Review of systems | |

| General Medical Physical Examination | |

| Cardiac Pulmonary Abdominal Other |

|

| Neurologic Physical Examination | |

| Level of consciousness Attention Orientation Memory General fund of knowledge Abstract thinking Insight and judgment Mood and affect |

|

| Communication | |

| Cranial nerve examination | |

| Sensation | |

| Motor control | Strength Coordination Apraxia Involuntary movements Tone |

| Reflexes | Superficial Deep Primitive |

| Musculoskeletal Physical Examination | |

| Inspection | Behavior Physical symmetry, joint deformity, etc. |

| Palpation | Joint stability Range of motion (active and passive) Strength testing (see above) Painful joints and muscles |

| Joint-specific provocative maneuvers |

An emergence in the use of electronic medical records (EMR) has significantly altered the landscape for documentation of the physiatric H&P in both the inpatient and outpatients settings.23 Among the advantages of the EMR are increased legibility, time efficiency afforded by the use of templates and “smart phrases” that can be tailored to individual practitioners, and automated warnings regarding medication interactions or errors, as well as faster and more accurate billing. Disadvantages include overuse of the “copy and paste” function, leading to the appearance of redundancy among consecutive notes and the perpetuation of potentially inaccurate information, automated importation of data not necessarily reviewed by the practitioner at the time of service, and “alarm fatigue.” As regulation of hospital and physician practice and billing increases, the EMR will become more important in ensuring the proper, and sometimes convoluted, documentation required for safety initiatives40 and physician payment.15

The Physiatric History

The time spent in taking a history also allows the patient to become familiar with the physician, establishing rapport and trust. This initial rapport is critical for a constructive and productive doctor–patient–family relationship and can also help the physician learn about such sensitive areas as the sexual history and substance abuse. It can also have an impact on outcome, as a trusting patient tends to be a more compliant patient.62 Assessing the tone of the patient and/or family (such as anger, frustration, resolve, and determination), understanding of the illness, insight into disability, and coping skills are also gleaned during history taking. In most cases, the patient leads the physician to a diagnosis and conclusion. In other cases, such as when the patient is rambling and disorganized, frequent redirection and refocus are required.

History of the Present Illness

The history of the present illness (HPI) details the chief complaint(s) for which the patient is seeking medical attention, as well as any related or unrelated functional deficits. It should also explore other information relating to the chief complaint such as recent and past medical or surgical procedures, complications of treatment, and potential restrictions or precautions. The HPI should include some or all of eight components related to the chief complaint: location, time of onset, quality, context, severity, duration, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms (see Table 1-2).

Functional Status

Assessing the potential for functional gain or deterioration requires an understanding of the natural history, cause, and time of onset of the functional problems. For example, most spontaneous motor recovery after stroke occurs within 3 months of the event.68 For a recent stroke patient with considerable motor impairments, there is a greater expectation for significant functional gain than in a patient with minor deficits related to a stroke that occurred 2 years ago.

It is sometimes helpful to assess functional status using a standardized scale. No single scale is appropriate for all patients, but the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is the most commonly used in the inpatient rehabilitation setting (Table 1-3; see Chapter 8).3 Measuring only activity limitation (disability) or performance, each of 18 different activities is scored on a scale of 1 to 7, with a score of 7 indicating complete independence. Intermediate scores indicate varying levels of assistance from very little (from an assistive device, to supervision, to hands-on assistance) to a score of 1 indicating complete dependence on caregiver assistance. FIM scores also serve as a kind of rehabilitation shorthand among team members to quickly and accurately describe functional deficits.

Table 1-3 Levels of Function on the Functional Independence Measure

| Level of Function | Score | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Independent |

From Anonymous3 1997, with permission of the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Mobility

Mobility is the ability to move about in one’s environment and is taken for granted by most healthy people. Because it plays such a vital role in society, any impairment related to mobility can have major consequences for a patient’s quality of life. A clear understanding of the patient’s functional mobility is needed to determine independence and safety, including the use of, or need for, mobility assistive devices. There is a range of mobility assistive devices that patients can use, such as crutches, canes, walkers, orthoses, and manual and electric wheelchairs (Table 1-4; see Chapters 15 and 17).

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Crutches |

Driving is a crucial activity for many people, not only as a means of transportation but also as an indicator and facilitator of independence. For example, elders who stop driving have an increase in depressive symptoms.50 It is important to identify factors that might prevent driving, such as decreased cognitive function and safety awareness, and decreased vision or reaction time. Other factors affecting driving can include lower limb weakness, contracture, tone, or dyscoordination. Some of these conditions might require use of adaptive hand controls for driving. Cognitive impairment sufficient to affect the ability to drive can be due to medications or organic disease (dementia, brain injury, stroke, or severe mood disturbance). Ultimately, the risks of driving are weighed against the consequences of not being able to drive. If the patient is no longer able to drive, alternatives to driving should be explored, such as the use of public or assisted transportation. Laws differ widely from state to state on the return to driving after a neurologic impairment develops.

Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

ADL encompass activities required for personal care including feeding, dressing, grooming, bathing, and toileting. I-ADL encompass more complex tasks required for independent living in the immediate environment such as care of others in the household, telephone use, meal preparation, house cleaning, laundry, and in some cases use of public transportation. In the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, there are 11 activities for both ADL and I-ADL (Box 1-1).4

BOX 1-1 Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (I-ADL)

Modified from [Anonymous]: Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: domain and process. Am J Occup Ther 56:609-639, 2002 (Erratum in: Am J Occup Ther 2003; 57:115) with permission.

The clinician should identify and document ADL the patient can and cannot perform, and determine the causes of limitation. For example, a woman with a stroke might state that she cannot put on her pants. This could be due to a combination of factors such as a visual field cut, balance problems, weakness, pain, contracture, hypertonia, or deficits in motor planning. Some of these factors can be confirmed later in the physical examination. A more detailed follow-up to a positive response to the question is frequently needed. For example, a patient might say “yes” to the question “Can you eat by yourself?” On further questioning, it might be learned that she cannot prepare the food by herself or cut the food independently. The most accurate assessment of ADL and mobility deficits often comes from the hands-on assessment by therapists and nurses on the rehabilitation team.

Cognition

Cognition is the mental process of knowing (see Chapters 3 and 4). Although objective assessment of cognition comes under physical examination (memory, orientation, and the ability to assimilate and manipulate information), impairments in cognition can also become apparent during the course of the history taking. Because persons with cognitive deficits often cannot recognize their own impairments (anagnosia), it is important to gather information from family members and others familiar with the patient. Cognitive deficits and limited awareness of these deficits are likely to interfere with the patient’s rehabilitation program unless specifically addressed. These deficits can pose a safety risk as well. For example, a man with a previous stroke who falls, sustaining a hip fracture requiring replacement, might not be able to follow hip precautions, resulting in possible refracture or hip dislocation. Executive functioning is another aspect of cognition, which includes the mental functions required for planning, problem solving, and self-awareness. Executive functioning correlates with functional outcome because it is required in many real-world situations.45

Past Medical and Surgical History

Musculoskeletal

There can be a wide range of musculoskeletal disorders from acute traumatic injuries to gradual functional decline with chronic osteoarthritis. The patient should be asked about a history of trauma, arthritis, amputation, joint contractures, musculoskeletal pain, congenital or acquired muscular problems, weakness, or instability. It is important to understand the functional impact of such impairments or disabilities. Patients with chronic physical disability often develop overuse musculoskeletal syndromes, such as the development of shoulder pain secondary to chronically propelling a wheelchair.33

Rheumatologic

The history should assess the type of rheumatologic disorder, time of onset, number of joints affected, pain level, current disease activity, and past orthopedic procedures. Discussions with the patient’s rheumatologist might address whether medication changes could improve activity tolerance in a rehabilitation program (see Chapter 36).

Medications

All medications should be documented including prescription and over-the-counter drugs, as well as nutraceuticals, supplements, herbs, and vitamins. Medications should be documented from both the last institutional venues (acute care, nursing home) and from home before institutionalization. Decreasing medication errors via medication reconciliation is a major thrust of the National Patient Safety Goals initiative.40 Patients typically do not mention medications that they do not think are relevant to their current problem, unless asked about them in detail. Drug and food allergies should be noted. It is especially important to gather the complete list of medications being used in patients who are seeing multiple physicians. Particular attention should be paid to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents because these are commonly prescribed by physiatrists for musculoskeletal disorders, and care must be taken not to double-dose the patient.27,32 The indications, precautions, and side effects of all drugs prescribed should be explained to the patient.

Social History

Substance Abuse

Patients should be asked about their history of smoking, alcohol use or abuse, and drug abuse. Because patients often deny substance abuse, this topic should be discussed in a nonjudgmental manner. Patients frequently feel embarrassment or guilt in admitting substance abuse, and also fear the legal consequences of such an admission. Substance abuse can be a direct and an indirect cause of disability, and is often a contributing factor in traumatic brain injury.19 It can also have an impact on community reintegration, because patients with pain and/or depression are at risk for further abuse. Patients who are at risk should be referred to social work to explore options for further assistance, either during the acute rehabilitation or later in the community.

Sexual History

Patients and health care practitioners alike are often uncomfortable discussing the topic of sexuality, so developing a good rapport during history taking can be helpful. Discussion of this topic is made easier if the health care practitioner has a basic knowledge of how sexual function can be changed by illness or injury (see Chapter 31). Sexuality is particularly important to patients in their reproductive years (such as with many spinal cord– and brain-injured persons), but the physician should enquire about sexuality in adolescents and adults, as well as in the elderly. Sexual orientation and safer sex practices should be addressed when appropriate.

Spirituality and Belief

Spirituality is an important part of the lives of many patients, and some preliminary studies indicate that it can have positive effects on rehabilitation, life satisfaction, and quality of life.13 Health care providers should be sensitive to the patient’s spiritual needs, and appropriate referral or counseling should be provided.17

Pending Litigation

Patients should be asked in a nonjudgmental fashion whether they are involved in litigation related to their illness, injuries, or functional impairment. The answer should not change the treatment plan, but litigation can be a source of anxiety, depression, or guilt. In some cases the patient’s legal representative can play an important role in obtaining needed services and equipment.

Review of Systems

A detailed review of organ systems should be done discover any problems or diseases not previously identified during the course of the history taking. Table 1-5 lists some questions that can be asked about each system.24 Note that this list is not comprehensive, and more detailed questioning might be necessary.

| System | Questions |

|---|---|

| Systemic | Any general symptoms such as fever, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, and poor appetite? |

| Skin | Any skin problems? Sores? Rashes? Growths? Itching? Changes in the hair or nails? Dryness? |

| Eyes | Any changes in vision? Pain? Redness? Double vision? Watery eyes? Dizziness? |

| Ears | How are the ears and hearing? Running ears? Poor hearing? Ringing ears? Discharge? |

| Nose | How are your nose and sinuses? Stuffy nose? Discharge? Bleeding? Unusual odors? |

| Mouth | Any problems with your mouth? Sores? Bad taste? Sore tongue? Gum trouble? |

| Throat and neck | Any problems with your throat and neck? Sore throat? Hoarseness? Swelling? Swallowing? |

| Breasts | Any problems with your breasts? Lumps? Nipple discharge? Bleeding? Swelling? Tenderness? |

| Pulmonary | Any problems with your lungs or breathing? Cough? Sputum? Bloody sputum? Pain in the chest on taking a deep breath? Shortness of breath? |

| Cardiovascular | Do you have any problems with your heart? Chest pain? Shortness of breath? Palpitations? Cough? Swelling of your ankles? Trouble lying flat in bed at night? Fatigue? |

| Gastrointestinal | How is your digestion? Any changes in your appetite? Nausea? Vomiting? Diarrhea? Constipation? Changes in your bowel habits? Bleeding from the rectum? Hemorrhoids? |

| Genitourinary | Male: Any problems with your kidneys or urination? Painful urination? Frequency? Urgency? Nocturia? |

| Bloody or cloudy urine? Trouble starting or stopping? | |

| Female: Number of pregnancies? Abortions? Miscarriages? Any menstrual problems? Last menstrual period? Vaginal bleeding? Vaginal discharge? Cessation of periods? Hot flashes? Vaginal itching? Sexual dysfunction? | |

| Endocrine | Any problems with your endocrine glands? Feeling hot or cold? Fatigue? Changes in the skin or hair? Frequent urination? Fatigue? |

| Musculoskeletal | Do you have any problems with your bones or joints? Joint or muscle pain? Stiffness? Limitation of motion? |

| Nervous system | Numbness? Weakness? Pins and needles sensation? |

From Enelow AJ, Forde DL, Brummel-Smith K: Interviewing and patient care, ed 4, New York, 1996, Oxford University Press,24 with permission of Oxford University Press.

The Physiatric Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

Weakness is a primary sign in neurologic disorders and is seen in both upper (UMN) and lower motor neuron (LMN) disorders. UMN lesions involving the central nervous system (CNS) are typically characterized by hypertonia, weakness, and hyperreflexia without significant muscle atrophy, fasciculation, or fibrillation (on electromyography). They tend to occur in a hemiparetic, paraparetic, and tetraparetic pattern. UMN etiologies include stroke, multiple sclerosis, traumatic and nontraumatic brain and spinal cord injuries, and neurologic cancers, among others. LMN defects are characterized by hypotonia, weakness, hyporeflexia, significant muscle atrophy, fasciculations, and electromyographic changes. They occur in the distribution of the affected nerve root, peripheral nerve, or muscle. UMN and LMN lesions often coexist; however, the LMN system is the final common pathway of the nervous system. An example of this is an upper trunk brachial plexus injury on the same side as spastic hemiparesis in a person with traumatic brain injury.51

Similar to physical examination in other organ systems, testing of one neurologic system is often predicated by the normal functioning of other systems. For example, severe visual impairment can be confused with cerebellar dysfunction, as many cerebellar tests have a visual component. The integrated functions of all organ systems should be considered to provide an accurate clinical assessment, and potential limitations of the examination should be considered.

Mental Status Examination

The mental status examination (MSE) should be performed in a comfortable setting where the patient is not likely to be disturbed by external stimuli such as televisions, telephones, pagers, conversation, or medical alarms. The bedside MSE is often limited secondary to distractions from within the room. Having a familiar person such as a spouse or relative in the room can often help reassure the patient. The bedside MSE might need to be supplemented by far more detailed and standardized evaluations performed by neuropsychologists, especially in cases of vocational and educational reintegration (see Chapters 4 and 35). Language is the gateway to assessing cognition and is therefore limited in persons with significant aphasia.

Level of Consciousness

The examiner should understand the various levels of consciousness. Lethargy is the general slowing of motor processes (such as speech and movement) in which the patient can easily fall asleep if not stimulated, but is easily aroused. Obtundation is a dulled or blunted sensitivity in which the patient is difficult to arouse, and once aroused is still confused. Stupor is a state of semiconsciousness characterized by arousal only by intense stimuli such as sharp pressure over a bony prominence (e.g., sternal rub), and the patient has few or even no voluntary motor responses.56 The Aspen Neurobehavioral Conference proposed, and several leading medical organizations have endorsed, three terms to describe severe alterations in consciousness.29 In coma, the eyes are closed with absence of sleep-wake cycles and no evidence of a contingent relationship between the patient’s behavior and the environment.29 Vegetative state is characterized by the presence of sleep-wake cycles but still no contingent relationship. Minimally conscious state indicates a patient who remains severely disabled but demonstrates sleep-wake cycles and even inconsistent, nonreflexive, contingent behaviors in response to a specific environmental stimulation. In the acute settings, the Glasgow Coma Scale is the most often used objective measure to document level of consciousness, assessing eye opening, motor response, and verbal response (Table 1-6).39

| Function | Rating |

|---|---|

| Eye opening | E |

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To speech | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| Nil | 1 |

| Best motor response | M |

| Obeys | 6 |

| Localizes | 5 |

| Withdraws | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion | 3 |

| Extensor response | 2 |

| Nil | 1 |

| Verbal response | V |

| Oriented | 5 |

| Confused conversation | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| Nil | 1 |

| Coma score (E + M + V) | 3-15 |

From Jennett B, Teasdale G: Assessment of impaired consciousness, Contemp Neurosurg 20:78, 1981 with permission.

Attention

Attention is the ability to address a specific stimulus for a short period without being distracted by internal or external stimuli.65 Vigilance is the ability to hold attention over longer periods. For example, with inadequate vigilance a patient can begin a complex task but be unable to sustain performance to completion. Attention is tested by digit recall, where the examiner reads a list of random numbers and the patient is asked to repeat those numbers. The patient should repeat digits both forward and backward. A normal performance is repeating seven numbers in the forward direction, with fewer than five indicating significant attention deficits.52,65

Orientation

Orientation is necessary for basic cognition. Orientation is composed of four parts: person, place, time, and situation. After asking the patient’s name, place can be determined by asking the location the patient is currently in or her or his home address. Time is assessed by asking the patient the time of day, the date, the day of the week, or the year. Situation refers to why the patient is in the hospital or clinic. Time sense is usually the first component lost, and person is typically the last to be lost. Temporary stress can account for a minor loss of orientation; however, major disorientation usually suggests an organic brain syndrome.69

Memory

The components of memory include learning, retention, and recall. During the bedside examination, the patient is typically asked to remember three or four objects or words. The patient is then asked to repeat the items immediately to assess immediate acquisition (encoding) of the information. Retention is assessed by recall after a delayed interval, usually 5 to 10 minutes. If the patient is unable to recall the words or objects, the examiner can provide a prompt (e.g., “It is a type of flower” for the word “tulip”). If the patient still cannot recall the words or objects, the examiner can provide a list from which the patient can choose (e.g., “Was it a rose, a tulip, or a daisy?”). Although abnormal scores must be interpreted within the context of the remaining neurologic examination, normal individuals younger than 60 years should recall three of four items.65

Recent memory can also be tested by asking questions about the past 24 hours, such as “How did you travel here?” or “What did you eat for breakfast this morning?” Assuming the information can be confirmed, remote memory is tested by asking where the patient was born or the school or college attended.46 Visual memory can be tested by having the patient identify (after a few minutes) four or five objects hidden in clear view.

Abstract Thinking

Abstraction is a higher cortical function and can be tested by the interpretation of common proverbs such as “a stitch in time saves nine” or “when the cat’s away the mice will play,” or by asking similarities, such as “How are an apple and an orange alike?” A concrete explanation for the first proverb would be “You should sew a rip before it becomes bigger,” whereas an abstract explanation would be “Quick attention to a given problem would prevent bigger troubles later.” An abstract response to the similarity would be “They are both kinds of fruit,” and a concrete response would be “They are both round” or “You can eat them both.” Most normal individuals should be able to provide abstract responses. A patient also demonstrates abstraction when he or she understands a humorous phrase or situation. Concrete responses are given by persons with dementia, mental retardation, or limited education. Abstract thinking should always be considered in the context of intelligence and cultural differences.69

Insight and Judgment

Insight has been conceptualized into three components: awareness of impairment, need for treatment, and attribution of symptoms. Insight can be ascertained by asking what brought the patient into the hospital or clinic.10 Recognizing that one has an impairment is the initial step for recovery. A lack of insight can severely hamper a patient’s progress in rehabilitation and is a major consideration in developing a safe discharge plan. Insight can be difficult to distinguish from psychological denial.

Judgment is an estimate of a person’s ability to solve real-life problems. The best indicator is usually simply observing the patient’s behavior. Judgment can also be assessed by noting the patient’s responses to hypothetical situations in relation to family, employment, or personal life. Hypothetical examples of judgment that reflect societal norms include “What should you do if you find a stamped, addressed envelope?” or “How are you going to get around the house if you have trouble walking?” Judgment is a complex function that is part of the maturational process and is consequently unreliable in children and variable in the adolescent years.69 Assessment of judgment is important to assess the patient’s capacity for independent functioning.

Mood and Affect

Mood can be assessed by asking the “Yale question”: “Do you often feel sad or depressed?”72 Establishing accurate information pertaining to the length of a particular mood is important. The examiner should document if the mood has been reactive (e.g., sadness in response to a recent disabling event or loss of independence), and whether the mood has been stable or unstable. Mood can be described in terms of being, including happy, sad, euphoric, blue, depressed, angry, or anxious.

Affect describes how a patient feels at a given moment, which can be described by terms such as blunted, flat, inappropriate, labile, optimistic, or pessimistic. It can be difficult to accurately assess mood in the setting of moderate to severe acquired brain injury. A patient’s affect is determined by the observations made by the examiner during the interview.11

General Mental Status Assessment

The Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination is a brief and convenient tool to test general cognitive function. It is useful for screening patients for dementia and brain injuries. Of a maximum 30 points, a score 24 or above is considered within the normal range.25 Also available is the easily administered Montreal Cognitive Assessment.54 The clock-drawing test is another quick test sensitive to cognitive impairment. The patient is instructed to “Without looking at your watch, draw the face of a clock, and mark the hands to show 10 minutes to 11 o’clock.” This task uses memory, visual spatial skills, and executive functioning. The drawing is scored on the basis of whether the clock numbers are generally intact or not intact out of a maximum score of 10.66 The use of the three-word recall test in addition to the clock-drawing test, which is known collectively as the Mini-Cog Test, has recently gained popularity in screening for dementia. The Mini-Cog can usually be completed within 2 to 3 minutes.60 The reader is referred to other excellent descriptions of the MSE for further reading.65

Communication

Aphasia

Aphasia involves the loss of production or comprehension of language. The cortical center for language resides in the dominant hemisphere. Naming, repetition, comprehension, and fluency are the key components of the physician’s bedside language assessment. The examiner should listen to the content and fluency of speech. Testing of comprehension of spoken language should begin with single words, progress to sentences that require only yes–no responses, and then progress to complex commands. The examiner should also assess visual naming, repetition of single words and sentences, word-finding abilities, and reading and writing from dictation and then spontaneously. Circumlocutions are phrases or sentences substituted for a word the person cannot express, such as responding “What you tell time with on your wrist” when asked to name a watch. Alexia without agraphia is seen in dominant occipital lobe injury. Here the patient is able to write letters and words from a spoken command but is unable to read the information after dictation.12 Some commonly used standardized aphasia measures include the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination and the Western Aphasia Battery (see Chapter 3).67

Dysarthria

Dysarthria refers to defective articulation, but with the content of speech unaffected. The examiner should listen to spontaneous speech and then ask the patient to read aloud. Key sounds that can be tested include “ta ta ta,” which is made by the tongue (lingual consonants); “mm mm mm,” which is made by the lips (labial consonants); and “ga ga ga,” which is made by the larynx, pharynx, and palate.46 There are several subtypes of dysarthria including spastic, ataxic, hypokinetic, hyperkinetic, and flaccid.52

Dysphonia

Dysphonia is a deficit in sound production and can be secondary to respiratory disease, fatigue, or vocal cord paralysis. The best method to examine the vocal cords is by indirect laryngoscopy. Asking the patient to say “ah” while viewing the vocal cords is used to assess vocal cord abduction. When the patient says “e,” the vocal cords will adduct. Patients with weakness of both vocal cords will speak in whispers with the presence of inspiratory stridors.46

Verbal Apraxia

Apraxia of speech involves a deficit in motor planning (i.e., awkward and imprecise articulation in the absence of impaired strength or coordination of the motor system). It is characterized by inconsistent errors when speaking. A difficult word might be spoken correctly, but trouble is experienced when repeating it. People with verbal apraxia of speech often appear to be “groping” for the right sound or word, and might try to speak a word several times before saying it correctly. Apraxia is tested by asking the patient to repeat words with an increasing number of syllables. Oromotor apraxia is seen in patients with difficulty organizing nonspeech, oral motor activity. This can adversely impact swallowing. Tests for oromotor apraxia include asking patients to stick out their tongue, show their teeth, blow out their cheeks, or pretend to blow out a match.1

Cranial Nerve Examination

Cranial Nerve I: Olfactory Nerve

The examiner should test both perception and identification of smell using aromatic nonirritating materials that avoid stimulation of the trigeminal nerve fibers in the nasal mucosa. Irritant substances such as ammonia should be avoided. The patient is asked to close the eyes while the opposite nostril is compressed separately. The patient should identify the smell in a test tube containing a common substance with a characteristic odor, such as coffee, peppermint, or soap. The olfactory nerve is the most commonly injured cranial nerve (CN) in head trauma, resulting from shearing injuries that can be associated with fractures of the cribiform plate.5

Cranial Nerve II: Optic Nerve

The optic nerve is assessed by testing for visual acuity and visual fields and by performing an ophthalmologic examination. Visual acuity refers to central vision, while visual field testing assesses the integrity of the optic pathway as it travels from the retina to the primary visual cortex. Testing visual fields by confrontation is most commonly performed. The patient faces the examiner while covering one eye so the other eye fixates on the opposite eye of the examiner directly in front. The examiner wiggles a finger at the outer boundaries of the four quadrants of vision while the patient points to the quadrant where he or she senses movement. More accurately, a red 5-mm pin can be used to map out the visual field.5 For patients with visual field and extraocular movement deficits (see following discussion), further assessment by a neurooptometrist or visually trained occupational therapists can be helpful.

Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI: Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Abducens Nerves

The primary action of the medial rectus is adduction (looking in) and that of the lateral rectus is abduction (looking out). The superior rectus and inferior oblique primarily elevate the eye, whereas the inferior rectus and superior oblique depress the eye. The superior oblique muscle controls gaze looking down, especially in adduction.46

Examination of the extraocular muscles involves assessing the alignment of the patient’s eyes while at rest and when following an object or finger held at an arm’s length. The examiner should observe the full range of horizontal and vertical eye movements in the six cardinal directions.5 The optic (afferent) and oculomotor (efferent) nerves are involved with the pupillary light reflex. A normal pupillary light reflex (CNs II and III) should result in constriction of both pupils when a light stimulus is present to either eye separately. A characteristic head tilt when looking down is sometimes seen in CN IV lesions.75

Cranial Nerve V: Trigeminal Nerve

The trigeminal nerve provides sensation to the face and mucous membranes of the nose, mouth, and tongue. There are three sensory divisions of the trigeminal nerve: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular branches. These branches can be tested by pinprick sensation, light touch, or temperature along the forehead, cheeks, and jaw on each side of the face. The motor branch of the trigeminal nerve also innervates the muscles of mastication, which include the masseters, the pterygoids, and the temporalis. The patient is asked to clamp the jaws together, and then the examiner will try to open the patient’s jaw by pulling down on the lower mandible. Observe and palpate for contraction of both the temporalis and the masseter muscles. The pterygoids are tested by asking the patient to open the mouth. If one side is weak, the intact pterygoid muscles will push the weak muscles, resulting in a deviation toward the weak side. The corneal reflex tests the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (afferent) and the facial nerve (efferent).

Cranial Nerve VIII: Vestibulocochlear Nerve

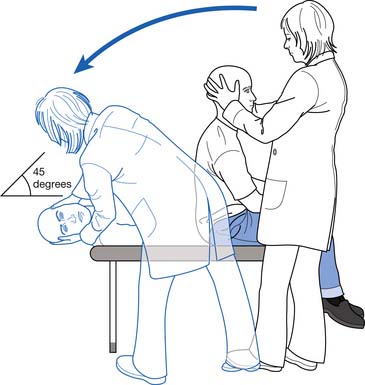

The vestibular division is seldom included in the routine neurologic examination. Patients with dizziness or vertigo associated with changes in head position or suspected of having benign paroxysmal positional vertigo should be assessed with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Figure 1-1). The absence of nystagmus indicates normal vestibular nerve function. With peripheral vestibular nerve dysfunction, however, the patient complains of vertigo, and rotary nystagmus appears after an approximately 2- to 5-second latency, toward the direction in which the eyes are deviated. With repetition of maneuvers, the nystagmus and sensation of vertigo fatigue and ultimately disappear. In central vestibular disease, such as from a stroke, the nystagmus has latency and is nonfatigable.26 Rehabilitation therapists with training in vestibular rehabilitation can also provide invaluable data for developing a differential diagnosis of balance deficits.

Cranial Nerves IX and X: Glossopharyngeal Nerve and Vagus Nerve

The glossopharyngeal nerve supplies taste to the posterior one third of the tongue, along with sensation to the pharynx and the middle ear. The glossopharyngeal nerve and vagus nerve are usually examined together. The patient’s voice quality should be noted, as hoarseness is usually associated with a lesion of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve. The patient is asked to open the mouth and say “ah.” The examiner should inspect the soft palate, which should elevate symmetrically with the uvula in midline. In an LMN vagus nerve lesion, the uvula will deviate to the side that is contralateral to the lesion. A UMN lesion presents with the uvula deviating toward the side of the lesion.31

The gag reflex can be tested by depressing the patient’s tongue with a tongue depressor and touching the pharyngeal wall with a cotton tip applicator until the patient gags. The examiner should compare the sensitivity of each side (afferent: glossopharyngeal nerve) and observe the symmetry of the palatal contraction (efferent: vagus nerve). The absence of a gag reflex indicates loss of sensation and/or loss of motor contraction. The presence of a gag reflex does not imply the ability to swallow without risk of aspiration (see Chapter 27).57

Cranial Nerve XI: Accessory Nerve

The accessory nerve innervates the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. While standing behind the patient, the examiner should look for atrophy or spasm in the trapezius and compare the symmetry of both sides. To test the strength of the trapezius, the patient is asked to shrug the shoulders and hold them in this position against resistance. To test the strength of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, ask the patient to rotate the head against resistance. The ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle turns the head to the contralateral side. The ipsilateral muscle brings the ear to the shoulder.

Cranial Nerve XII: Hypoglossal Nerve

The hypoglossal nerve is a pure motor nerve innervating the muscles of the tongue. It is tested by asking the patient to protrude the tongue, noting evidence of atrophy, fasciculation, or deviation. Fibrillations in the tongue are common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.30 The tongue typically points to the side of the lesion in peripheral hypoglossal nerve lesions, but toward the opposite side of the lesion in UMN lesions such as stroke.

Sensory Examination

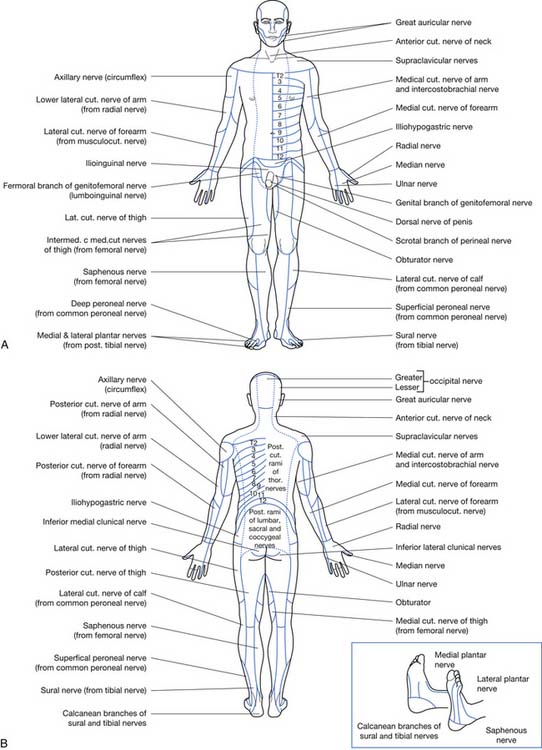

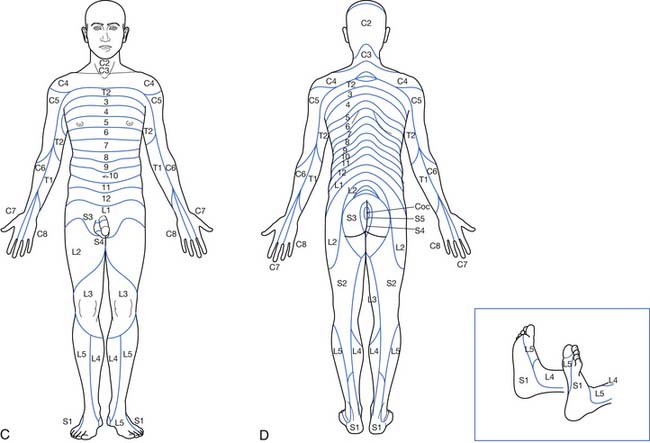

The examiner should be familiar with the normal dermatomal and peripheral nerve sensory distribution (Figure 1-2). Evaluation of the sensory system requires testing of both superficial sensation (light touch, pain, and temperature) and deep sensation (involves the perception of position and vibration from deep structures such as muscle, ligaments, and bone).

FIGURE 1-2 Distribution of peripheral nerves and dermatomes.

(Redrawn from Haymaker W, Woodhall B: Peripheral nerve injuries, Philadelphia, 1953, Saunders, with permission.)

Light touch can be assessed with a fine wisp of cotton or a cotton tip applicator. The examiner should touch the skin lightly, avoiding excessive pressure. The patient is asked to respond when a touch is felt, and to say whether there is a difference between the two sides. Pain and temperature both travel via the spinothalamic tracts and are assessed using a safety pin or other sharp sanitary object, while occasionally interspersing the examination with a blunt object. Patients with peripheral neuropathy might have a delayed pain appreciation and often change their minds a few seconds after the initial stimuli. Some examiners use the single or double pinprick of brief duration to test for pain, while others use a continuous sustained pinprick to better test for delayed pain.50 Temperature testing is not often used and rarely provides additional information, but it is sometimes easier for patients to delineate insensate areas. Thermal sensation can be checked by using two different test tubes, one filled with hot water (not hot enough to burn) and one filled with cold water and ice chips.

Two-point discrimination is most commonly tested using calipers with blunt ends. The patient is asked to close the eyes and indicate if one or two stimulation points are felt. The normal distance of separation that can be felt as two distinct points depends on the area of body being tested. For example, the lips are sensitive to a point separation of 2 to 3 mm, normally identified as two points. Commonly tested normal two-point discrimination areas include the fingertips (3 to 5 mm), the dorsum of the hand (20 to 30 mm), and the palms (8 to 15 mm).46

Motor Control

Coordination

The cerebellum is divided into three areas: the midline, the anterior lobe, and the lateral hemisphere. Lesions affecting the midline usually produce truncal ataxia in which the patient cannot sit or stand unsupported. This can be tested by asking the patient to sit at the edge of the bed with the arms folded so they cannot be used for support. Lesions that affect the anterior lobe usually result in gait ataxia. In this case, the patient is able to sit or stand unsupported but has noticeable balance deficits on walking. Lateral hemisphere lesions produce loss of ability to coordinate movement, which can be described as limb ataxia. The affected limb usually has diminished ability to correct and change direction rapidly. Tests that are typically used to test for limb coordination include the finger-to-nose test and the heel-to-shin test.51

The Romberg test can be used to differentiate a cerebellar deficit from a proprioceptive one. The patient is asked to stand with the heels together. The examiner notes any excessive postural swaying or loss of balance. If loss of balance is present when the eyes are open and closed, the examination is consistent with cerebellar ataxia. If the loss of balance occurs only when the eyes are closed, this is classically known as a positive Romberg sign indicating a proprioceptive (sensory) deficit.46

Apraxia

Apraxia is the loss of the ability to carry out programmed or planned movements despite adequate understanding of the tasks. This deficit is present even though the patient has no weakness or sensory loss. To accomplish a complex act, there first must be an idea or a formulation of a plan. The formulation of the plan then must be transferred into the motor system where it is executed. The examiner should watch the patient for motor-planning problems during the physical examination. For example, a patient might be unable to perform transfers and other mobility tasks but has adequate strength on formal manual muscle testing.

Ideomotor apraxia associated with a lesion of the dominant parietal lobe occurs when a patient cannot carry out motor commands but can perform the required movements under different circumstances. These patients usually can perform many complex acts automatically but cannot carry out the same acts on command. Ideational apraxia refers to the inability to carry out sequences of acts, although each component can be performed separately. Other forms of apraxia are constructional, dressing, oculomotor, oromotor, verbal, and gait apraxia. Dressing and constructional apraxia are often related to impairments of the nondominant parietal lobe, which typically are the result of neglect rather than actual deficit in motor planning.46

Involuntary Movements

Documenting involuntary movements is important in the overall neurologic examination. A careful survey of the patient usually shows the presence or absence of voluntary motor control. Tremor is the most common type of involuntary movement and is a rhythmic movement of a body part. Lesions in the basal ganglia produce characteristic movement disorders. Chorea describes movements that consist of brief, random, nonrepetitive movements in a fidgety patient unable to sit still. Athetosis consists of twisting and writhing movements and is commonly seen in cerebral palsy. Dystonia is a sustained posturing that can affect small or large muscle groups. An example is torticollis, in which dystonic neck muscles pull the head to one side. Hemiballismus occurs when there are repetitive violent flailing movements that are usually caused by deficits in the subthalamic nucleus.52

Tone

Tone is the resistance of muscle to stretch or passive elongation (see Chapter 30). Spasticity is a velocity-dependent increase in the stretch reflex, whereas rigidity is the resistance of the limb to passive movement in the relaxed state (non–velocity dependent). Variability in tone is common, as patients with spasticity can vary in their presentation throughout the day and with positional changes or mood. Some patients will demonstrate little tone at rest (static tone) but experience a surge of tone when they attempt to move the muscle during a functional activity (dynamic tone). Accurate assessment of tone might require repeated examinations.56

Initial observation of the patient usually shows abnormal posturing of the limbs or trunk. Palpation of the muscle also provides clues, because hypotonic muscles feel soft and flaccid on palpation, whereas hypertonic muscles feel firm and tight. Passive range of motion (ROM) provides information about the muscle in response to stretch. The examiner provides firm and constant contact while moving the limbs in all directions. The limb should move easily and without resistance when altering the direction and speed of movement. Hypertonic limbs feel stiff and resist movement, while flaccid limbs are unresponsive. The patient should be told to relax because these responses should be examined without any voluntary control. Clonus is a cyclic alternation of muscular contraction in response to a sustained stretch, and is assessed using a quick stretch stimulus that is then maintained. Myoclonus refers to sudden, involuntary jerking of a muscle or group of muscles. Myoclonic jerks can be normal because they occasionally happen in normal individuals and are typically part of the normal sleep cycle. Myoclonus can result from hypoxia, drug toxicity, and metabolic disturbances. Other causes include degenerative disorders affecting the basal ganglia and certain dementias.61

Tone can be quantified by the Modified Ashworth Scale, a six-point ordinal scale. A pendulum test can also be used to quantify spasticity. While in the supine position, the patient is asked to fully extend the knee and then allow the leg to drop and swing like a pendulum. A normal limb swings freely for several cycles, whereas a hypertonic limb quickly returns to the initial dependent starting position.67

The Tardieu Scale has been suggested to be a more appropriate clinical measure of spasticity than the Modified Ashworth Scale. It involves assessment of resistance to passive movement at both slow and fast speeds. Measurements are usually taken at 3 velocities (V1, V2, and V3). V1 is taken as slow as possible, slower than the natural drop of the limb segment under gravity. V2 is taken at the speed of the limb falling under gravity. V3 is taken with the limb moving as fast as possible, faster than the natural drop of the limb under gravity. Responses are recorded at each velocity and the degrees of angle at which the muscle reaction occurs.34

Reflexes

Superficial Reflexes

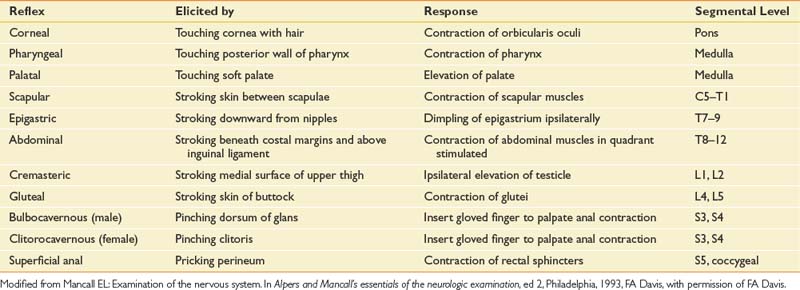

The plantar reflex is the most common superficial reflex examined. A stimulus (usually by the handle end of a reflex hammer) is applied on the sole of the foot from the lateral border up and across the ball of the foot. A normal reaction consists of flexion of the great toe or no response. An abnormal response consists of dorsiflexion of the great toe with an associated fanning of the other toes. This response is the Babinski sign and indicates dysfunction of the corticospinal tract but no further localization. Stroking from the lateral ankle to the lateral dorsal foot can also produce dorsiflexion of the great toe (Chaddock sign). Flipping the little toe outward can produce the upgoing great toe also, and is called the Stransky sign. Other superficial reflexes include the abdominal, cremasteric, bulbocavernous, and superficial anal reflexes (Table 1-7).52

Muscle Stretch Reflexes

Muscle stretch reflexes (which in the past were called deep tendon reflexes) are assessed by tapping over the muscle tendon with a reflex hammer (Table 1-8). In order to elicit a response, the patient is positioned into the midrange of the arc of joint motion and instructed to relax. Tapping of the tendon results in visible movement of the joint. The response is assessed as 0, no response; 1+, diminished but present and might require facilitation; 2+, usual response; 3+, more brisk than usual; and 4+, hyperactive with clonus. If muscle stretch reflexes are difficult to elicit, the response can be enhanced by reinforcement maneuvers such as hooking together the fingers of both hands while attempting to pull them apart (Jendrassik maneuver). While pressure is still maintained, the lower limb reflexes can be tested. Squeezing the knees together and clenching the teeth can reinforce responses to the upper limbs.46

| Muscle | Peripheral nerve | Root level |

|---|---|---|

| Biceps | Musculocutaneous nerve | C5, C6 |

| Brachioradialis | Radial nerve | C5, C6 |

| Triceps | Radial nerve | C7, C8 |

| Pronator teres | Median nerve | C6, C7 |

| Patella (quadriceps) | Femoral nerve | L2–L4 |

| Medial hamstrings | Sciatic (tibial portion) nerve | L5–S1 |

| Achilles | Tibial nerve | S1, S2 |

Primitive Reflexes

Primitive reflexes are abnormal adult reflexes that represent a regression to a more infantile level of reflex activity. Redevelopment of an infantile reflex in an adult suggests significant neurologic abnormalities. Examples of primitive reflexes include the sucking reflex, in which the patient sucks the area around which the mouth is stimulated. The rooting reflex is elicited by stroking the cheek, resulting in the patient turning toward that side and making sucking motions with the mouth. The grasp reflex occurs when the examiner places a finger on the patient’s open palm. Attempting to remove the finger causes the grip to tighten. The snout reflex occurs when a lip-pursing movement occurs when there is a tap just above or below the mouth. The palmomental response is elicited by quickly scratching the palm of the hand. A positive reflex is indicated by sudden contraction of the mentalis (chin) muscle. It arises from unilateral damage of the prefrontal area of the brain.53

Gait

Gait evaluation is an important and often neglected part of the neurologic evaluation. Gait is described as a series of rhythmic, alternating movements of the limbs and trunks that result in the forward progression of the center of gravity.9 Gait is dependent on input from several systems including the visual, vestibular, cerebellar, motor, and sensory systems. The cause of dysfunction can be determined by understanding the aspects of gait involved. One example is difficulty getting up, which is consistent with Parkinson’s disease, or a lack of balance and wide-based gait, which is suggestive of cerebellar dysfunction.

| Gait Type | Disease or Anatomic Location | Gait Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hemiplegic | Unilateral upper motor neuron lesions with spastic hemiplegia | The affected lower limb is difficult to move, and knee is held in extension. With ambulation, the leg swings away from the center of the body, and the hip hikes upward to prevent the toes and foot from striking the floor. This is known as “circumduction.” If the upper limb is involved, there may be decreased arm swing with ambulation.30 The upper limb has a flexor synergy pattern resulting in shoulder adduction, elbow and wrist flexion, and a clinched fist. |

| Scissoring | Bilateral corticospinal tract lesions often seen in patients with cerebral palsy, incomplete spinal cord injury, and multiple sclerosis | Hypertonia in the legs and hips results in flexion and the appearance of a crouched stance. The hip adductors are overactive causing the knees and thighs to touch or cross in a “scissor-like” movement. In cerebral palsy, there can be associated ankle plantar flexion forcing the patient to tiptoe walk. The step length is shortened by the severe adduction or scissoring of the hip muscles.30 |

| Ataxic | Cerebellar dysfunction or severe sensory loss (such as tabes dorsalis) | Ataxic gait is characterized by a broad-based stance and irregular step and stride length. In ataxic gait from proprioceptive dysfunction (tabes dorsalis), gait will markedly worsen with the eyes closed. There is a tendency to sway, while watching the floor usually helps guide the uncertain steps. Ataxic gait from cerebellar dysfunction will not worsen with eyes closed. Movement of the advancing limb starts slowly, and then there is an erratic movement forward or laterally. The patient will try to correct the error but usually overcompensates. Tandem gait exacerbates cerebellar ataxia.74 |

| Myopathic | Myopathies cause weakness of the proximal leg muscles. | Myopathies result in a broad-based gait and a “waddling-type” appearance as the patient tries to compensate for pelvic instability. Patients will have problems with climbing stairs or rising from a chair without using their arms. When going floor to standing, the patient will use their arms and hands to climb up their legs—known as Gower’s sign.13 |

| Trendelenberg | Caused by weakness of the abductor muscles (gluteus medius and gluteal minimus) as in superior gluteal nerve injury, poliomyelitis, or myopathy | During the stance phase, the abductor muscle allows the pelvis to tilt down on the opposite side. In order to compensate, the trunk lurches to the weakened side to maintain the pelvis level during the gait cycle. This results in a waddling-type gait with an exaggerated compensatory sway of the trunk toward the weight-bearing side. It is important to understand that the pelvis sags on the opposite side of the weakened abductor muscle.13 |

| Parkinsonian | Seen in Parkinson’s disease and other disorders of the basal ganglia | Patients have a stooped posture, narrow base of support, and a shuffling gait with small steps. As the patient starts to walk, the movements of the legs are usually slow with the appearance of the feet sticking to the floor. They might lean forward while walking so the steps become hurried, resulting in shuffling of the feet (festination). Starting, stopping, or changing directions quickly is difficult, and there is a tendency for retropulsion (falling backwards when standing). The whole body moves rigidly requiring many short steps and there is loss of normal arm swing. There can be a “pill-rolling” tremor while the patient walks.74 |

| Steppage | Diseases of the peripheral nervous system including L5 radiculopathy, lumbar plexopathies, and peroneal nerve palsy | The patient with foot drop has difficulty dorsiflexing the ankle. The patient compensates for the foot drop by lifting the affected extremity higher than normal to avoid dragging the foot. Weak dorsiflexion leads to poor heel strike with the foot slapping on the floor.30 An ankle-foot orthosis can be helpful. |

| Apraxic | Gait impairment when there is no evidence of sensory loss, weakness, vestibular dysfunction, or cerebellar deficit; seen in frontal lobe injuries such as a stroke and traumatic brain injury | Despite difficulty with ambulation, patients can perform complex coordinated activities with the lower limbs.70 |

Musculoskeletal Examination

Caveats

The musculoskeletal examination (MSK examination) confirms the diagnostic impression and lays the foundation for the physiatric treatment plan. It incorporates inspection, palpation, passive and active ROM, assessment of joint stability, manual muscle testing and joint-specific provocative maneuvers, or special tests (Table 1-10).28,35,48 The functional unit of the musculoskeletal system is the joint. The comprehensive examination of a joint includes related structures such as muscles, ligaments, and the synovial membrane and capsule.63 The physiatric MSK examination also indirectly tests coordination, sensation, and endurance.28,44 There is overlap between the examination (and clinical presentation) of the neurologic and musculoskeletal systems. The primary impairment in many cases in neurologic disease is the secondary musculoskeletal complications of immobility and suboptimal movement (in which the concept of the kinetic chain is important for evaluation). The MSK examination should be performed in a routine sequence for efficiency and consistency, and must be approached with a solid knowledge of the anatomy. The reader is referred to several excellent references that provide in-depth reviews of the MSK examination.∗

| Test | Description | Reliability (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical Spine Tests | ||

| Spurling’s/neck compression test | A positive test is reproduction of radicular symptoms distant from the neck with passive lateral flexion and compression of the head. | |

Modified from Malanga GA, Nadler SF, editors: Musculoskeletal physical examination: an evidence-based approach, Philadelphia, 2006, Mosby.

Inspection and Palpation

Inspection of the musculoskeletal system begins during the history. Attention to subtle cues and behaviors can guide the approach to the examination. Inspection includes observing mood, signs of pain or discomfort, functional impairments, or evidence of malingering. The spine should be specifically inspected for scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis. Limbs should be examined for symmetry, circumference, and contour. In persons with amputation, the level, length, and shape of the residual limb should be noted. Depending on the clinical situation, it can be important to assess for muscle atrophy, masses, edema, scars, and fasciculations.63 Joints should be inspected for abnormal positions, swelling, fullness, and redness.

Palpation is used to confirm initial impressions from inspection, helping to determine the structural origins of soft tissue or bony pain and localize trigger points, muscle guarding, or spasm and referred pain.63 Joints and muscles should be assessed for swelling, warmth, masses, tight muscle bands, tone, and crepitus.36 Tone is typically determined while assessing the ROM. It is important to palpate the limbs and cranium for evidence of fracture in patients with a change in mental status after a fall or trauma.52

Assessment of Joint Stability

The assessment of joint stability judges the capacity of structural elements to resist forces in nonanatomic directions.52,63 Stability is determined by several factors including bony congruity, capsular and cartilaginous integrity, and the strength of ligaments and muscles.52 Assessing the “normal” side establishes a patient’s unique biomechanics. The examiner first identifies pain and resistance in the affected joint, followed by an evaluation of joint play to assess “end feel,” capsular patterns, and hypomobility or hypermobility. Radiographic imaging can be helpful in cases of suspected instability—for example, flexion-extension spine films to assess vertebral column instability or magnetic resonance imaging to visualize the degree of anterior cruciate ligament rupture.

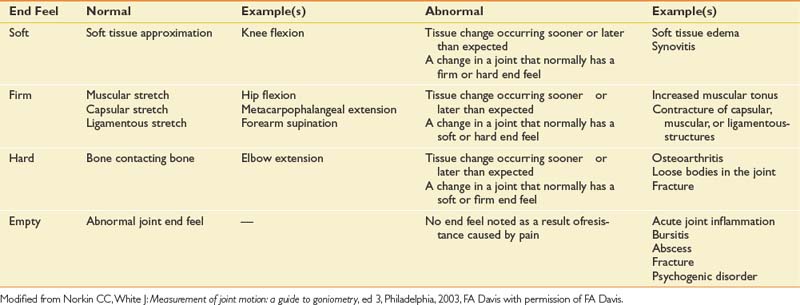

Joint play or capsular patterns assess the integrity of the capsule in an open-packed position. Open-packed refers to positions in which there is minimal bony contact with maximum capsular laxity.58 Voluntary movement of a joint (active ROM) does not generally exploit the fullest range of that joint. Extreme end ranges of joint movements not under voluntary control must be assessed by passive ROM. There are several types of end feels (Table 1-11). Soft tissue compression is normal in extreme elbow flexion, yet if felt sooner than expected can indicate inflammation or edema. Tissue stretch is usually firm yet slightly forgiving, such as in hip flexion. Firmness that occurs before the end point of range, however, can be a sign of increased tone and/or capsular tightening. A hard end feel is normally seen with elbow extension, but in an arthritic joint it can occur before full range is achieved. An “empty” feel suggests an absence of mechanical restriction due to muscle contraction caused by pain. With muscle involuntary guarding or spasm, one notes an abrupt stop associated with pain.

It is important to differentiate between hypomobile and hypermobile joints. The former increase the risk for muscle strains, tendonitis, and nerve entrapments, while the latter increase the risk for joint sprains and degenerative joint disease.58 An inflammatory synovitis, for example, can increase joint mobility and weaken the capsule. In the setting of decreased muscle strength, the risk of trauma and joint instability is increased.52 If joint instability is suspected, confirmatory diagnostic testing can be done (e.g., radiography).21,37,41,47 The temporal relationship between pain and resistance on examination actually changes from acute to chronic injury. An acute joint demonstrates pain before resistance to passive ROM. In a subacute joint, there is pain at the same time as resistance to passive ROM. In a chronic joint, pain occurs after resistance to ROM is noted.58

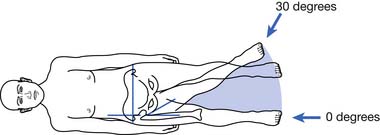

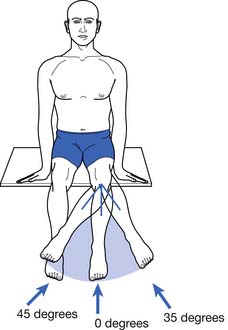

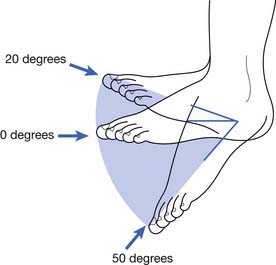

Assessment of Range of Motion

General Principles

ROM testing is used to document the integrity of a joint, to assess the efficacy of treatment regimens, and to determine the mechanical cause of an impairment.40 Limitations not only affect ambulation and mobility, but also ADL. Normal ROM varies based on age, gender, conditioning, obesity, and genetics.52 Males have a more limited range when compared with females, depending on age and specific joint action.8 Vocational and avocational patterns of activity also potentially alter ROM. For example, gymnasts generally have increased ROM at the hips and lower trunk.58 Passive ROM should be performed through all planes of motion by the examiner in a relaxed patient to thoroughly assess end feel.58 Active ROM performed by the patient through all planes of motion without assistance from the examiner simultaneously evaluates muscle strength, coordination of movement, and functional ability.

Assessment Techniques

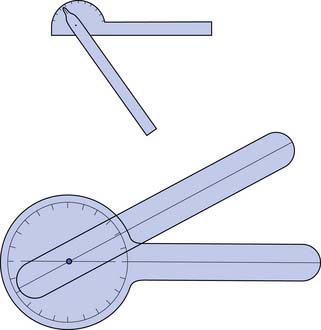

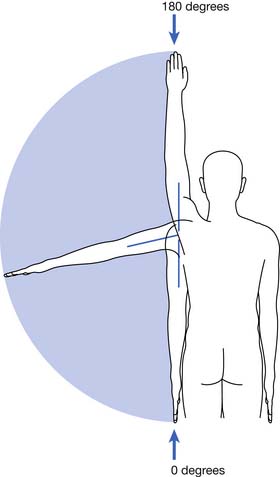

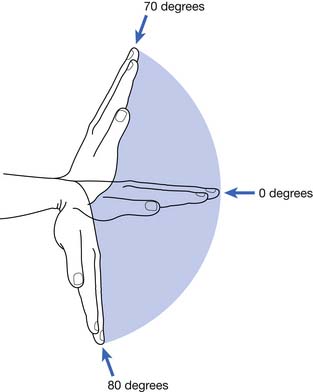

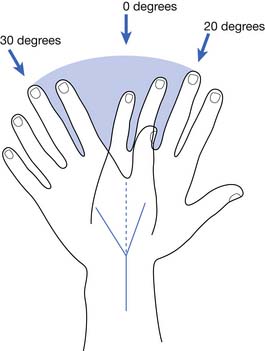

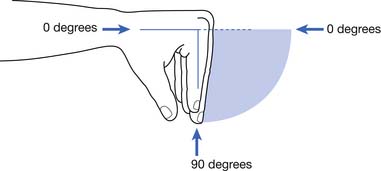

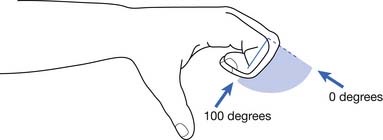

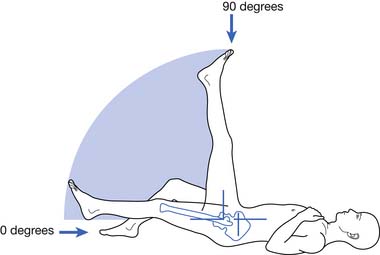

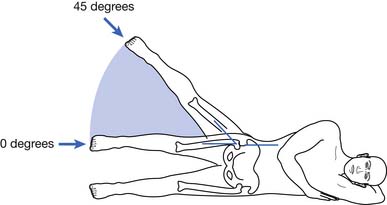

ROM should be performed before strength testing. ROM is a function of joint morphology, capsule and ligament integrity, and muscle and tendon strength.58,63 Range is measured with a universal goniometer, a device that has a pivoting arm attached to a stationary arm divided into 1-degree intervals (Figure 1-3). Regardless of the type of goniometer used, reliability is increased by knowing and using consistent surface landmarks and test positions.28 Joints are measured in their plane of movement with the stationary arm parallel to the long axis of the proximal body segment or bony landmark.58 The moving arm of the goniometer should also be aligned with a bony landmark or parallel to the moving body segment. The impaired joint should always be compared with the contralateral unimpaired joint, if possible.

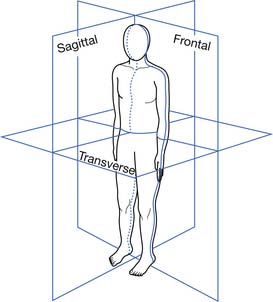

Sagittal, frontal, and coronal planes divide the body into three cardinal planes of motion (Figure 1-4). The sagittal plane divides the body into left and right halves, the frontal (coronal) plane, into anterior and posterior halves; and the transverse plane, into superior and inferior parts.28 For sagittal plane measurements, the goniometer is placed on the lateral side of the joint, except for a few joint motions such as forearm supination and pronation. Frontal planes are measured anteriorly or posteriorly, with the axis coinciding with the axis of the joint.

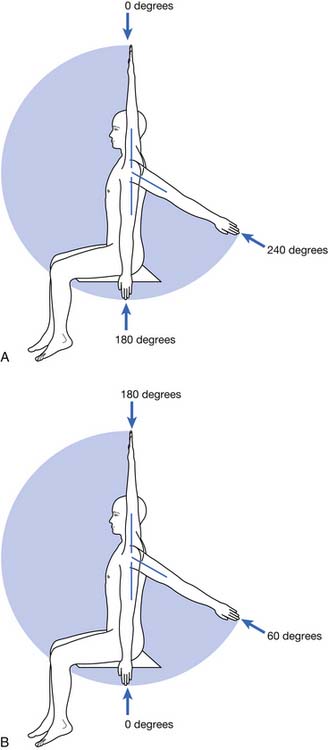

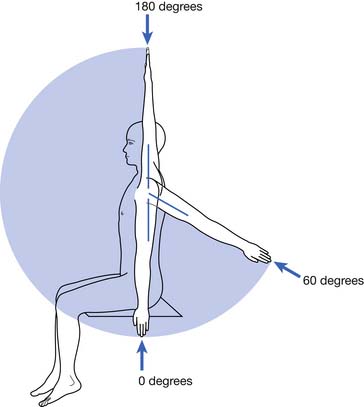

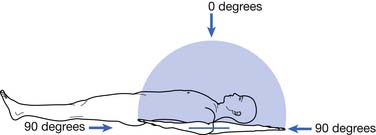

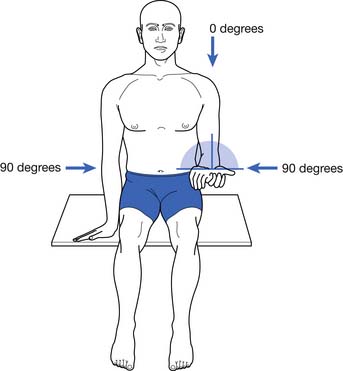

The 360-degree system was first proposed by Knapp and West42,43 and denotes 0 degrees directly overhead and 180 degrees at the feet. In the 360-degree system, shoulder forward flexion and extension ranges from 0 to 240 degrees (Figure 1-5, A). The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons uses a 180-degree system.55 The standard anatomic position14 is described as an upright position with the feet facing forward, the arms at the side with the palms facing anterior.28 A joint at 0 degrees is in the anatomic position, with movement occurring up to 180 degrees away from 0 degrees in either direction.28 With the use of shoulder forward flexion as an example, the normal range for flexion in the 180-degree system is 0 to 180 degrees, and for extension is 0 to 60 degrees (Figure 1-5, B). These standardized techniques have been well described.∗

Figures 1-6 through 1-21 outline the correct patient positioning and plane of motion for the joint and goniometer placement. To increase accuracy, many practitioners recommend taking several measurements and recording a mean value.58 Measurement inaccuracy can be as high as 10% to 30% in the limbs and can be without value in the spine if based on visual assessment alone.2,71 In joint deformity, the starting position is the actual starting position of joint motion. Spinal ROM is more difficult to measure, and its reliability has been debated.28,36 The most accurate method of measuring spinal motion is with radiographs. Because this is not practical in most clinical scenarios, the next most accurate system is based on inclinometers. These are fluid-filled instruments with a 180- or 360-degree scale. One or two devices are required.2,36 The American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment2 outlines the specific inclinometer techniques for measuring spinal ROM.

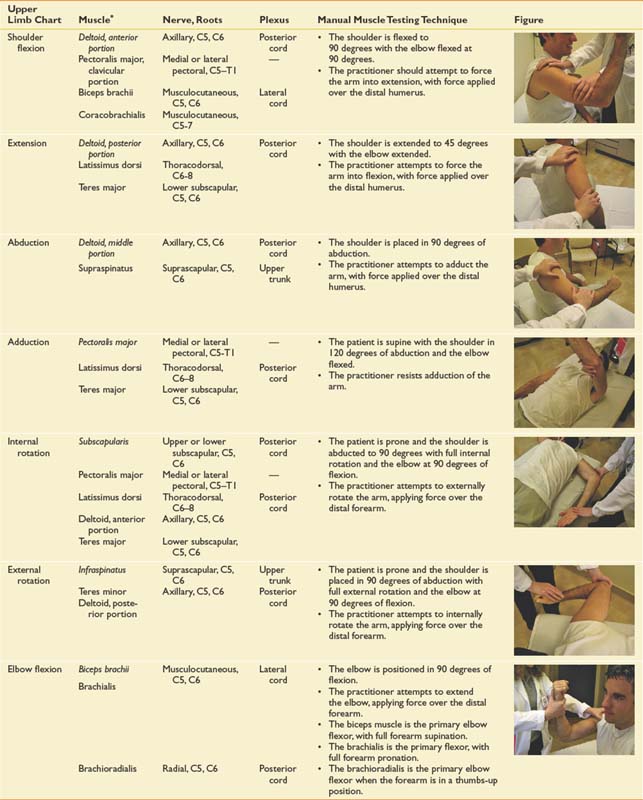

Assessment of Muscle Strength

General Principles

Manual muscle testing is used to establish baseline strength, to determine the functional abilities of or need for adaptive equipment, to confirm a diagnosis, and to suggest a prognosis.58 Strength is a rather generic term and can refer to a wide variety of assessments and testing situations.6 Manual muscle testing specifically measures the ability to voluntarily contract a muscle or muscle group at a specific joint. It is quantified using a system first described by Robert Lovett, M.D., an orthopedic surgeon, in the early twentieth century.20 Isolated muscles can be difficult to assess. For example, elbow flexion strength depends not only on the biceps muscle but also on the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles. Strength is affected by many factors including the number of motor units firing, functional excursion, cross-sectional area of the muscle, line of pull of the muscle fibers, number of joints crossed, sensory receptors, attachments to bone, age, sex, pain, fatigue, fear, motivational level, and misunderstanding.6,52,58 Pain can result in breakaway weakness caused by pain inhibition of function and should be documented as such. It is important to recognize the presence of substitution when muscles are weak or movement is uncoordinated. Females typically increase strength up to age 20 years, plateau through their 20s, and gradually decline in strength after age 30. Males increase strength up to age 20 and then plateau until somewhat older than 30 years before declining.58 Muscles that are predominantly type 1 or slow-twitch fibers (e.g., soleus muscle) tend to be fatigue resistant and can require extended stress on testing (such as several standing toe raises) to uncover weakness.58 Type 2 or fast-twitch fibers (e.g., sternocleidomastoid) fatigue quickly, and weakness can be more straightforward to uncover abnormalities. Patients who cannot actively control muscle tension (e.g., those with spasticity from CNS disease) are not appropriate for standard manual muscle testing methods.58

Assessment Techniques

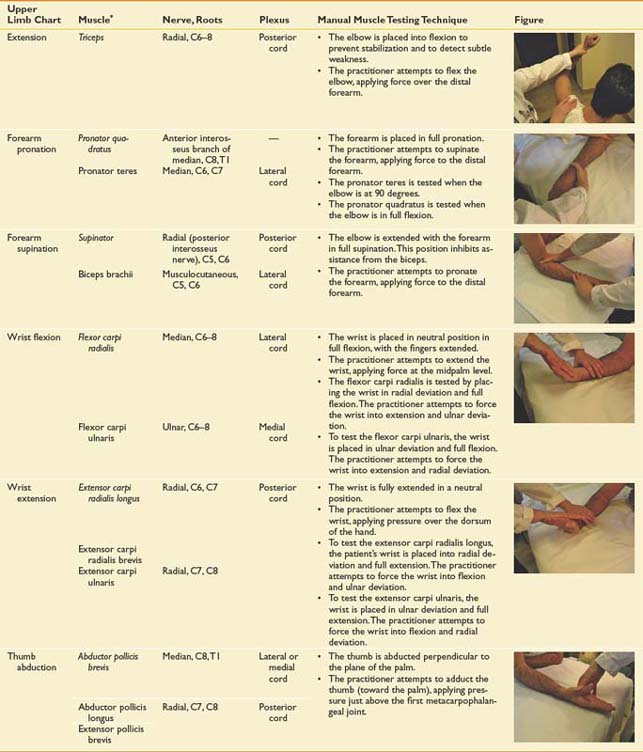

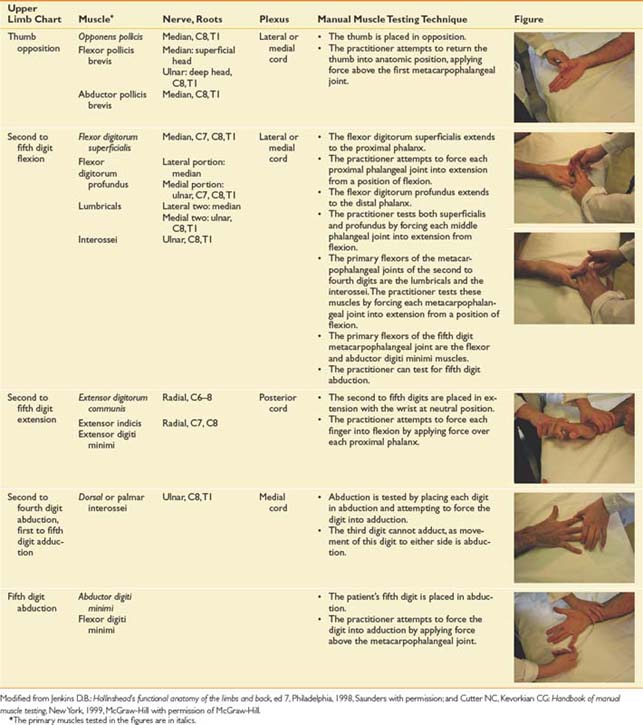

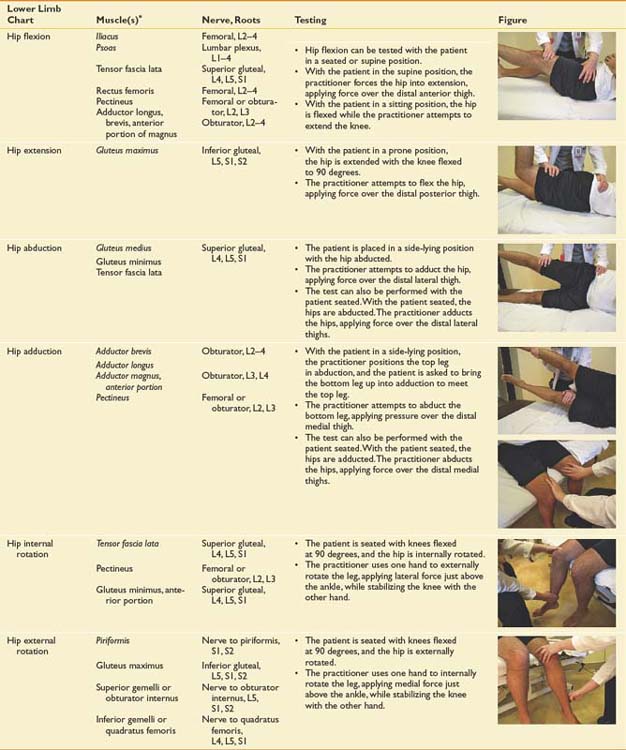

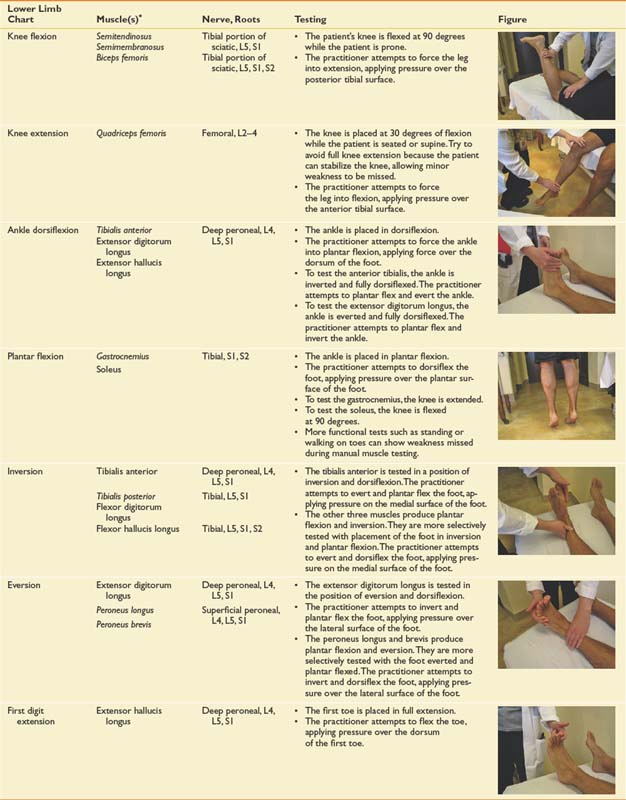

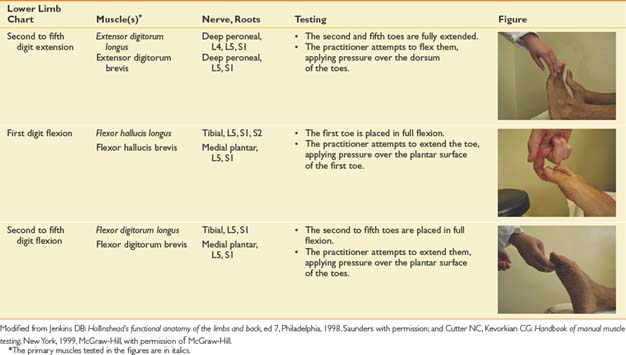

Manual muscle testing takes into account the weight of the limb without gravity, with gravity, and with gravity plus additional manual resistance.58 Most examiners use the Medical Research Council scale, where grades of 0 to 2 indicate gravity-minimized positions, and grades 3 to 5 indicate increasing degrees of resistance applied as an isometric hold at the end of the test range (Table 1-12).58 A muscle grade of 3 is functionally important because antigravity strength implies that a limb can be used for activity, whereas a grade of less than 3 implies that the limb will require external support and is prone to contracture.63 A 1- or 2-grade intertester difference is acceptable,58 but poor intertester reliability can be a problem with grades below 3.6 Other pitfalls encountered in testing strength are outlined in Table 1-13. To reduce measurement errors, one hand should be placed above and one below the joint being tested. As detailed in extended Tables 1-14 and 1-15, the examiner’s hands should not cross two joints, if possible. Placing a muscle at a mechanical disadvantage, such as flexing the elbow beyond 90 degrees to assess triceps strength, can help demonstrate mild weakness.36 Extended Tables 1-14 and 1-15 summarize the joint movement, innervation, and manual strength testing techniques for all major upper and lower extremity muscle groups, respectively. The use of a dynamometer can add a degree of objectivity to measurements for pinch and grip.

| Grade | Term | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Normal | Full available ROM is achieved against gravity and is able to demonstrate maximal resistance. |

| 4 | Good | Full available ROM is achieved against gravity and is able to demonstrate moderate resistance. |

| 3 | Fair | Full available ROM is achieved against gravity but is not able to demonstrate resistance. |

| 2 | Poor | Full available ROM is achieved only with gravity eliminated. |

| 1 | Trace | A visible or palpable contraction is noted, with no joint movement. |

| 0 | Zero | No contraction is identified. |

ROM, Range of motion.

Modified from Cutter NC, Kevorkian CG: Handbook of manual muscle testing, New York, 1999, McGraw-Hill with permission of McGraw-Hill.

Table 1-13 Caveats in Manual Muscle Resting

| Caveat | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Isolation | It is important to isolate individual muscles with similar functions instead of testing the entire muscle group. |

| Substitution patterns | It is important to be aware of basic substitution patterns (e.g., elbow flexion). |

| Suboptimal testing conditions | These occur when determining patients’ muscle strength when they are under the influence of, for example, sedation, significant pain, positioning, language or cultural barriers, spasticity, and hypertonicity. |

| Overgrading | This occurs when the practitioner applies increased force when the patient is unable to achieve the full available ROM yet is able to demonstrate a muscle grade of 3 or more in a lengthened position. |

| Undergrading | This occurs when the examiner is not aware of the effects of muscle contracture on ROM, and the muscle appears to lack full ROM when it has achieved its full available ROM. |

ROM, Range of motion.

Modified from Cutter NC, Kevorkian CG: Handbook of manual muscle testing, New York, 1999, McGraw-Hill with permission of McGraw-Hill.

Dynamic screening tests of strength can also be done. A quick screen for upper extremity strength is to have the patient grasp two of the examiner’s fingers while the examiner attempts to free the fingers by pulling in all directions. For a proximal lower limb screen, the patient can demonstrate a deep knee bend (squat and rise), and for the distal lower extremity can walk on heels and toes. To make gait abnormalities more evident, patients can be asked to increase the speed of their cadence, and walk sideways and backward. Abdominal strength can be screened by observing the patient’s ability to go from supine to sitting with the hips and knees bent. If the hips and knees are extended, the iliopsoas is tested as well.36

Assessment, Summary, and Plan

With a medical and functional problem list in hand, the management plan can be developed. Considering six broad interventional categories as originally outlined by Stolov et al.64 is very helpful, particularly with complex patients in an inpatient rehabilitation setting. These six categories include prevention or correction of additional disability, enhancement of affected systems, enhancement of unaffected systems, use of adaptive equipment, use of environmental modification, and use of psychologic techniques to enhance patient performance and education. The physician should clearly delineate the therapeutic precautions for the other team members. Both short- and longer-term goals should be outlined, as well as estimated time frames for achieving those goals. Boxes 1-2 and 1-3 show examples of rehabilitation plans for an inpatient after subarachnoid hemorrhage and an outpatient with back pain, respectively.

Box 1-2 Inpatient Rehabilitation Plan

Rehabilitation Problem List and Management Plan

Medical Problem List and Management Plan

Box 1-3 Outpatient Rehabilitation Plan

Rehabilitation Problem List and Management Plan

Medical Problem List and Management Plan

Summary

Physiatrists should pride themselves in their ability to complete a comprehensive rehabilitation H&P. The physiatric H&P begins with the standard medical format but goes beyond that to assess impairment, activity limitation (disability), and participation (handicap). Physiatrists’ understanding of the musculoskeletal examination and musculoskeletal principles is a primary distinction from neurologists and neurosurgeons. Similarly, physiatrist’s understanding of neurology and the neurologic examination is a primary distinction from orthopaedists and rheumatologists. The H&P is critical in gathering the information needed to formulate a treatment plan that can help the patient achieve the appropriate goals in the most efficient, least dangerous, and most cost-effective way possible.

1. Adams R.D., Victor M. Principles of neurology, ed 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. American Medical Association. Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, ed 4. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1993.

3. [Anonymous]. Guide for the uniform data set for medical rehabilitation, version 5.1. Buffalo: State University of New York at Buffalo; 1997.