Chapter 12

The Peripheral Vascular System

Veins which by the thickening of their tunicles in the old restrict the passage of blood, and by this lack of nourishment destroy their life without any fever, the old coming to fail little by little in slow death.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

General Considerations

Diseases of the peripheral vascular system are common and may involve the arteries, veins, or lymphatic vessels. The arterial conditions include cerebrovascular, aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, renal, aortic occlusive, and aneurysmal diseases. The two most important diseases of the peripheral arteries are atherosclerosis of the larger arteries and microvascular disease. Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) is a nearly pandemic condition that has the potential to cause loss of limb or even loss of life.

The most common cause of peripheral arterial occlusive disease is atherosclerosis affecting the medium-sized and large vessels of the extremities. Narrowing of the vessel causes a decreased blood supply, resulting in ischemia. PVD is a common disorder that usually affects men older than age 50. People are at higher risk if they have a history of:

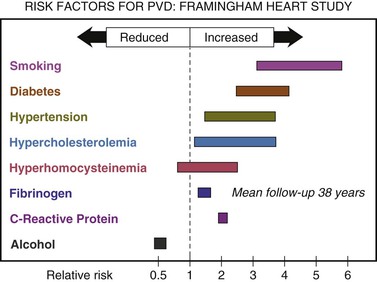

Figure 12-1 summarizes the risk factors for PVD according to the Framingham Heart Study.1

The classic symptoms of PVD are pain, heaviness, fatigue, burning, or discomfort in the muscles of your feet, calves, or thighs. These symptoms usually appear during walking or exercise and go away after several minutes of rest. At first, these symptoms may appear only when the patient walks uphill, walks faster, or walks for longer distances. Slowly, these symptoms come on more quickly and with less exercise. The legs or feet may feel numb while at rest. The legs also may feel cool to the touch, and the skin may look pale. When peripheral artery disease becomes severe, the patient may experience:

• Pain that is worse when raising the leg and improves when dangling the legs over the side of the bed

Atherosclerosis may become manifest by aneurysmal dilatation. The abdominal aorta is commonly affected. The aneurysm is commonly below the renal arteries and may extend as far as the external iliac arteries. Often, this aneurysm produces few, if any, symptoms. The examiner may discover a pulsatile mass as an incidental finding. Frequently, the first manifestation is the catastrophic rupture of the aneurysm. An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) larger than 5 cm in diameter carries a 20% risk of rupturing within the first year of discovery and a 50% risk of rupturing within 5 years.

Vesalius described the first AAA in the sixteenth century. Before the development of a surgical intervention for the process, attempts at medical management failed. The initial surgical attempts at control entailed ligation of the aorta with poor results. In 1923, Rudolph Matas performed the first successful aortic ligation on a patient. Attempts were made to induce thrombosis by inserting intraluminal wires. In 1948, C. E. Rea wrapped reactive cellophane around the aneurysm to induce fibrosis and limit expansion. This technique was used on Albert Einstein in 1949, and he survived 6 years before dying of rupture. However, not until 1951 was an abdominal aneurysm surgically treated by resection and grafting. In that year, C. Dubost performed the first AAA repair with a homograft. Since then, great strides have been made in understanding the natural history of vascular disease, as well as in developing new technology to help diagnose and treat it.

In autopsy studies, the frequency rate of AAA ranges from 0.5% to 3.2%. In a large U.S. Veterans Administration screening study, the prevalence rate was 1.4%. The frequency of rupture is 4.4 cases per 100,000 persons. AAA is 5 times more common in men than in women and is 3.5 times more common in white men than in African-American men. The likelihood of development varies from 3 to 117 cases per 100,000 person-years.

Microvascular arterial disease occurs in patients with diabetes. Changes develop in the small arterioles that impair circulation to the skin or nerves, especially of the lower extremities, producing symptoms of ischemia. Peripheral neuropathy is a common sequela of microvascular disease. This neuropathy may be manifested as a defect in the sensory, motor, or autonomic system. Microvascular disease affects more than 15 million individuals in the United States. In diabetic patients, there is the tragic “Rule of 15,” which states that:

• Fifteen percent of all diabetics will develop a foot ulcer sometime in life.

• Fifteen percent of those foot ulcers will lead to osteomyelitis.

Also, in diabetic patients, the “Rule of 50” states that:

• Fifty percent of amputations are at the transfemoral/transtibial level.

• Fifty percent of patients have a second amputation in 5 years or less.

Peripheral venous disease often progresses to venous stasis and thrombotic disorders. One of the dreaded complications of thrombotic disease is pulmonary embolism. In the United States, more than 175,000 deaths per year are attributed to acute pulmonary embolism.

Structure and Physiology

Diseases of the peripheral arterial system cause ischemia of the extremities. When the body is at rest, collateral blood vessels may be able to provide adequate circulation. During exercise, when oxygen demand increases, this circulation may not be sufficient for the actively contracting muscles, and ischemia may result.

The venous system consists of a series of low-pressure capacitance vessels. Nearly 70% of the blood volume is contained in this system. Although offering little resistance, the veins are controlled by a variety of neural and humoral stimuli that enhance venous return to the right side of the heart. In addition, valves aid in the return of blood.

When an individual is in the upright posture, the venous pressure in the lower extremity is the highest. Over many years, the veins dilate as a result of weakening of their walls. As the walls dilate, the veins are unable to close adequately, and reflux of blood occurs. In addition, the venous pump becomes less efficient in returning blood to the heart. Both of these factors are responsible for the venous stasis seen in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Complications from venous stasis include pigmentation, dermatitis, cellulitis, ulceration, and thrombus formation.

The lymphatic system is an extensive vascular network and is responsible for returning tissue fluid (lymph) back to the venous system. The extremities are richly supplied with lymphatic tissue. Lymph nodes, many of which are located between major proximal joints, aid in filtering the lymphatic fluid before it enters the blood. The most important clinical symptoms of lymphatic obstruction are lymphedema and lymphangitis.

Review of Specific Symptoms

Many patients with PVD are asymptomatic. When patients are symptomatic, vascular disease causes the following:

Pain

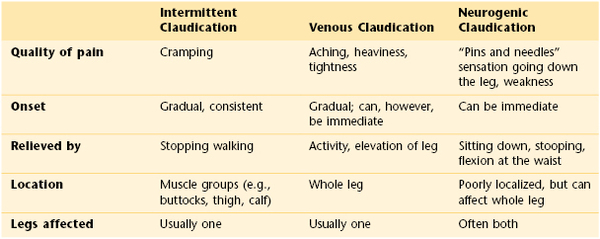

Pain is the principal symptom of atherosclerosis. Whenever a patient complains of pain in the calf, arch of the foot, thighs, hips, or buttocks while walking, PVD of the arteries must be considered. The symptom of pain in the lower extremity during exercise and relieved by rest is called intermittent claudication. The site of the pain is always distal to the occlusive disease. Supply does not equal demand. As the disease progresses, pain at rest occurs. This is often severe and is aggravated by cool temperatures and elevation, especially during sleep in bed. Pain may also occur with deep vein thrombosis, a condition known as venous claudication. It is the combination of venous valvular incompetence, outflow obstruction, and calf muscle pump function derangement that generates the hemodynamic setting most often associated with the development of venous claudication. A unique feature of venous claudication is that motionless standing is often more difficult than walking. This is because contraction of the muscles in our legs while walking pumps the blood through the veins and back to the heart. Neurogenic claudication is a common symptom of lumbar spinal stenosis, or inflammation of the nerves emanating from the spinal cord. The pain is often related to posture. The combination of the stenosis with certain back postures such as arching puts pressure on lumbosacral nerve roots and the cauda equina. Table 12-1 describes the differences between intermittent claudication, venous claudication, and neurogenic claudication.

If a male patient complains of pain in the buttocks, hips, or thighs while walking, the examiner should inquire about erectile dysfunction. The patient may also experience leg numbness or weakness. Leriche’s syndrome is chronic aortoiliac obstruction; the patient presents with intermittent claudication and erectile dysfunction. In this condition, the terminal aorta and iliac arteries are involved by severe atherosclerosis at the aortic bifurcation.

Patients occasionally complain of bilateral leg pain or numbness that occurs while walking, as well as while resting. This is called pseudoclaudication and is a symptom of musculoskeletal disease in the lumbar area.

Skin Changes

Skin color changes are common with vascular disease. In chronic arterial insufficiency, the affected extremity is cool and pale. In chronic venous insufficiency, the extremity is warmer than normal. The leg becomes erythematous, and erosions produced by excoriation result. With chronic insufficiency, stasis changes produce increased pigmentation, swelling, and an “aching” or “heaviness” in the legs. These changes characteristically occur in the lower third of the extremity and are more prominent medially. When venous insufficiency occurs, edema of dependent areas results.

Patients with acute deep vein thrombosis have secondary inflammation of the tissue surrounding the vein. This produces signs of inflammation: warmth, redness, and fever. Swelling is the most reliable symptom and sign associated with venous obstruction. This finding is indicative of severe deep vein obstruction because the superficial veins of the lower extremity carry only 20% of the total drainage and are not associated with swelling. The extremities should be compared, and a difference in circumference of 2 cm at the ankle or midcalf should be considered significant.

Edema

Lymphedema results from either a primary abnormality in the development of the lymphatic system or an acquired obstruction to flow. Whether the congenital or the acquired form is involved, the net result is stasis of lymph fluid in the tissues, producing a firm, nonpitting edema. Over several years, the skin takes on a rough consistency similar to that of pigskin. Because lymphedema is usually painless, the only symptom is “heaviness” of the extremity.

Ulceration

Persistent ischemia of a limb is associated with ischemic ulceration and gangrene. Ulceration is almost inevitable once skin has thickened and the circulation is compromised. Ulceration related to arterial insufficiency occurs as a result of trauma to the toes and heel. These ulcers are painful, have discrete edges that produce a “punched-out” appearance, and are often covered with crust. When infected, the tissue is erythematous.

In contrast to arterial insufficiency ulceration, venous insufficiency leads to stasis ulceration, which is painless and occurs in the ankle area or lower leg just above the medial malleolus. The classic manifestation is a diffusely reddened, thickened area over the medial malleolus. The skin has a cobblestone appearance resulting from fibrosis and venous stasis. Ulceration occurs with the slightest trauma. Rapidly developing ulcers are commonly caused by arterial insufficiency, whereas slowly developing ulceration is usually the result of venous insufficiency. Figures 12-2 and 12-3 show stasis dermatitis and ulcerations over the medial malleoli. Patients with leg ulcers should be asked the following:

Emboli

A history of emboli is important. Thrombus formation results from stasis and hypercoagulability. It appears, however, that venous stasis is the most important cause of thrombus formation. Bed rest, congestive heart failure, obesity, pregnancy, recent extended travel on airplanes, and oral contraceptives have been linked to thrombus formation and emboli.

Symptoms secondary to emboli can include shortness of breath from pulmonary emboli; abdominal pain from splenic, intestinal, or renal artery emboli; neurologic symptoms from carotid or vertebrobasilar artery emboli; and pain and paresthesias from peripheral artery emboli.

Neurologic Symptoms

Cerebrovascular occlusive disease causes many neurologic symptoms, including strokes,2 dizziness, and changes in consciousness. Occlusion of the internal carotid artery produces a syndrome of contralateral hemiplegia, contralateral sensory deficits, and dysphasia. Vertebrobasilar disease is associated with diplopia, cerebellar dysfunction, changes in consciousness, and facial paresis.

Effect of Vascular Disease on the Patient

A patient with chronic arterial insufficiency has worsening pain while walking. As the condition progresses, ulceration of the toes, feet, and areas susceptible to trauma, such as the shins, develops. Pain may become excruciating. Gangrene of a toe may develop, and amputation of the toe is frequently followed by amputation of the foot and leg. In addition, the patient becomes increasingly depressed as a result of ongoing mutilation of the body.

Physical Examination

The equipment necessary for the examination of the peripheral vascular system consists of a stethoscope, a tourniquet, and a tape measure.

The physical examination of the peripheral vascular system consists of inspection, palpation of the arterial pulses, and some additional tests if disease is thought to be present. All these techniques are usually integrated with the rest of the physical examination.

The patient lies supine, with the examiner standing to the right of the bed. The evaluation of the peripheral vascular system includes the following:

Inspection

Inspect for Symmetry of the Extremities

The extremities should be compared for asymmetries in size, color, temperature, and venous patterns. Figure 12-4 depicts massive lymphedema of the right upper extremity secondary to a right total mastectomy 18 years earlier.

Figure 12–4 Lymphedema.

Inspect the Lower Extremities

The lower extremities should be inspected for pigmentary abnormalities, ulcers, edema, and venous patterns. Is cyanosis present? Is edema present? If edema is present, does it pit? Bilateral color changes and swelling of the legs of the patient are pictured in Figure 12-5. The patient had chronic venous insufficiency. She died of a massive pulmonary embolus 1 day after this photograph was taken.

Figure 12–5 Chronic venous insufficiency.

Assess the Skin Temperature

Evaluate the temperature by using the back of your hand. Compare similar areas of each extremity. Coolness of an extremity is common with arterial insufficiency.

Inspect for Varicosities

Ask the patient to stand, and inspect the lower extremities for varicosities. Look at the area of the proximal femoral ring, as well as in the distal portion of the legs. Varicose veins in these locations may not have been visible when the patient was lying down.

The patient in Figure 12-6 was a 37-year-old woman with severe right-sided heart failure. Notice the marked dilated and tortuous veins in the popliteal fossa. Also notice the increased pigmentation of the skin over the lower legs. Figure 12-7 shows another patient, 65 years of age, with marked bilateral lower extremity varicosities extending from the groin down the entire legs. Despite their appearance, she suffered no other symptoms.

Figure 12–6 Marked varicosities of the popliteal fossa.

Examination of the Arterial Pulses

The most important finding when the peripheral arterial tree is examined is a decreased or absent pulse. The radial, brachial, femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses are routinely evaluated although examination of the arterial pulses may miss up to 50% of PVD.

Palpate the Radial Pulse

You should stand in front of the patient. The radial pulses are evaluated by grasping both of the patient’s wrists and palpating the pulses with your index, middle, and fourth fingers. Hold the patient’s right wrist with your left fingers and the patient’s left wrist with your right fingers, as demonstrated in Figure 11-22. The symmetry of the pulses is evaluated for timing and strength.

Palpate the Brachial Pulse

Because the brachial pulse is stronger than the digital pulses, the examiner may use his or her thumbs to palpate the patient’s brachial pulses. The brachial artery can be felt medially just under the belly or tendon of the biceps muscle. With the examiner still standing in front of the patient, both brachial arteries can be palpated simultaneously. The examiner’s left hand holds the patient’s right arm, and the examiner’s right hand holds the patient’s left arm. Once the examiner’s thumbs feel the brachial pulsation, the examiner should apply progressive pressure to it until the maximal systolic force is felt. Figure 12-8 shows an alternate method of evaluating the brachial artery pulse bilaterally at the same time. The examiner should now be able to assess its wave form.

Figure 12–8 Technique for brachial artery palpation.

Auscultate the Carotid Artery

Auscultation for carotid bruits3 is performed by placing the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the patient’s carotid artery while the patient is lying supine. This is demonstrated in Figure 12-9. The patient’s head should be slightly elevated on a pillow and turned slightly away from the carotid artery being evaluated. It is often helpful to ask the patient to hold his or her breath during the auscultation. Normally, either nothing or transmitted heart sounds are heard. After one carotid artery is evaluated, the other is examined. After auscultation of the carotid arteries, they are palpated (see Chapter 11, The Heart).

The presence of a murmur should be noted. This may be a bruit resulting from atherosclerotic disease of the carotid artery. On occasion, loud murmurs originating from the heart can be transmitted to the neck. With experience, the examiner is able to determine whether the disorder is local in the neck or distal in the heart.

Palpate the Abdominal Aorta

AAAs kill approximately 10,000 people in the United States each year. Many of these deaths could be prevented if the patients were aware of the presence of this defect. Once the defect is recognized, the rate of operative mortality for a nonruptured aneurysm is less than 5%, and after operation, the survival rate equals that of the general population. An AAA that ruptures carries a mortality rate of nearly 90%. Even among patients who reach the operating room alive, the surgical mortality rate is 50%.

The examination is performed by palpating deeply, but gently, into the midabdomen. The presence of a mass with laterally expansive pulsation suggests an AAA. The sensitivity of aortic palpation to find AAA is 60%, and the sensitivity of finding a pulsatile mass is only 50% of patients with diagnosed aortic ruptures. Some caution is urged in making this diagnosis in thin individuals, in whom the normal pulsatile aorta can be easily palpated. The high false-positive rate with this examination should not be a problem, however, because confirmation with abdominal ultrasonography is safe and inexpensive.

Other findings associated with an AAA include an abdominal bruit, a femoral bruit, and a femoral pulse deficit. In fewer than 10% of patients with AAAs, a bruit may be present. Acute rupture of an AAA is suggested when a bruit is associated with severe pain in the abdomen or back and when the distal pulse is absent or diminished and later returns.

Table 12-2 summarizes the operating characteristics of the physical signs useful for detecting an AAA.

Table 12–2

Characteristics of Physical Signs for Detecting an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

| Physical Sign | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Definite pulsatile mass | 28 | 97 |

| Definite or suggestive pulsatile mass | 50 | 91 |

| Abdominal bruit | 11 | 95 |

| Femoral bruit | 17 | 87 |

| Femoral pulse deficit | 22 | 91 |

Data from Lederle FA, Walker JM, Reinke DB: Selective screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms with physical examination and ultrasound, Arch Intern Med 148:1753, 1988.

Rule Out Abdominal Bruits

The patient should be supine. The examiner places the diaphragm of the stethoscope in the midline of the patient’s abdomen about 2 inches (5 cm) above the umbilicus and listens carefully for the presence of an aortic bruit. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 12-10.

Figure 12–10 Technique for auscultation of the abdominal aorta.

Abdominal bruits that are present only during systole are frequently of little clinical value because they are found in normal individuals and in patients with essential hypertension. The presence of a systolic-diastolic abdominal bruit, however, should raise the suspicion of renovascular hypertension. Nearly 60% of all patients with renovascular hypertension have such a bruit.

The presence of a combined systolic-diastolic abdominal bruit has a sensitivity of 39% and a specificity of 99% for detecting renovascular hypertension. The presence of this type of bruit has a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 39 and, if absent, a negative likelihood ratio (LR−) of 0.6. In a study that evaluated the presence of any epigastric or flank bruit and its association with renovascular hypertension, the sensitivity was 63%, but the specificity dropped to 90%. The presence of any abdominal bruit confers a much lower LR+ for renovascular hypertension (i.e., 6.4).

Palpate the Femoral Pulse and Rule Out Coarctation of the Aorta

The femoral pulse is evaluated with the patient lying on the back and the examiner at the patient’s right side. The lateral corners of the pubic hair triangle are observed and palpated. The femoral artery should run obliquely through the corner of the pubic hair triangle inferior to the inguinal ligament at a point midway between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine. Both femoral pulses may be compared simultaneously. The technique is demonstrated in Figure 12-11.

Figure 12–11 Technique for palpation of the femoral arteries.

If one of the femoral pulses is diminished or absent, auscultation for a bruit is necessary. The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed over the femoral artery. The presence of a bruit may indicate obstructive aortoiliofemoral disease.

The timing of the femoral and radial pulses is important. Normally, these pulses peak either at the same time or with the femoral pulse preceding the radial pulse. By placing one hand on the patient’s femoral artery and the other on the radial artery, the examiner can determine the peaking of these pulses. This technique need be performed on one side only. Any delay in the femoral pulse should raise suspicion of coarctation of the aorta, especially in a hypertensive individual. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 12-12.

Figure 12–12 Technique for timing the femoral and radial pulses.

Palpate the Popliteal Pulse

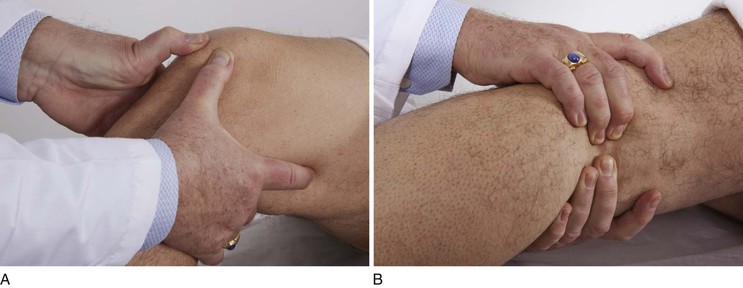

The popliteal artery is often difficult to assess. Each artery is evaluated separately. While the patient is lying on the back, the examiner’s thumbs are placed on the patella, and the remaining fingers of both hands are pressed in the popliteal fossa medial to the lateral biceps femoris tendon, as demonstrated in Figure 12-13. The examiner should hold the leg in a mild degree of flexion. The patient should not be asked to elevate the leg, because this tightens the muscles and makes it more difficult to feel the pulse. The examiner should squeeze both hands in the popliteal fossa. Firm pressure is usually necessary to feel the pulsation.

Palpate the Dorsalis Pedis Pulse

The dorsalis pedis pulse is best palpated when the foot is dorsiflexed. The dorsalis pedis artery passes along a line from the extensor retinaculum of the ankle to a point just lateral to the extensor tendon of the great toe. It is usually easily palpated in the groove between the extensor digitorum longus and hallucis longus tendon. The dorsalis pedis pulses may be felt simultaneously, as demonstrated in Figure 12-14.

Palpate the Posterior Tibial Pulse

The posterior tibial artery can be palpated just posterior to the medial malleoli between the tibialis posterior tendon and the flexor digitorum longus tendon. Both arteries can be evaluated simultaneously. Figure 12-15 demonstrates this procedure. Although posterior tibial pulses are absent in 15% of normal subjects, the most sensitive sign of occlusive peripheral arterial disease in patients older than 60 years of age is the absence of the posterior tibial pulse.

Grading of Pulses

The description of the amplitude of the pulse is most important. The following is the most widely accepted grading system:

It is important that the patient’s socks or stockings be removed when the examiner assesses the peripheral pulses of the lower extremities. If there is confusion about whether you are feeling the patient’s pulse or your own pulse, you can palpate the patient’s pulse with your right hand and use your left hand to palpate your own right radial pulse. If the pulses are different, you are feeling the patient’s pulse with your right hand.

Examination of the Lymphatic System

Physical signs of lymphatic system disease include the following:

Lymph nodes should be described as painless or tender and as single or matted. Generalized lymphadenopathy and localized lymphadenopathy are suggestive of different diagnoses. Generalized lymphadenopathy is the presence of palpable lymph nodes in three or more lymph node chains. Lymphoma, leukemia, collagen vascular disorders, and systemic bacterial, viral, and protozoal infections may be responsible. Localized lymphadenopathy is usually the result of localized infection or neoplasm.

Lymphangitis is defined as an inflammation of the lymphatic channels that occurs as a result of infection at a site distal to the lymphatic channel. When pathogens enter the lymphatic channels, invading directly through trauma to the skin, local inflammation and subsequent infection ensue, manifested as red streaks on the skin, the hallmark of lymphangiitis. The inflammation or infection then extends proximally toward regional lymph nodes. Bacteria can grow rapidly in the lymphatic system. Individuals with lymphangitis often have fever, chills, and malaise, and some may report a headache, loss of appetite, and muscle aches. Lymphangitis can progress rapidly to bacteremia and disseminated infection, particularly when caused by species of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, which are the most common causes of lymphangitis. Individuals with diabetes, immunodeficiency, varicella, chronic steroid use, or other systemic illnesses have an increased risk of developing serious or rapidly spreading lymphangitis.

Obstruction to lymphatic flow produces lymphedema, which is usually indistinguishable from other types of edema. In Figure 13-8, the patient has marked lymphedema of her left arm secondary to inflammatory breast carcinoma.

The examinations for lymphadenopathy of the head, neck, and supraclavicular areas are described in Chapter 6, The Head and Neck, and in Chapter 10, The Chest. Chapter 13, The Breast, describes the examination for palpating axillary adenopathy. Chapter 15, Male Genitalia and Hernias, describes the technique for palpating inguinal lymph nodes. The only other important lymph node chain is the epitrochlear nodes, discussed in the following section.

Palpate for Epitrochlear Nodes

To palpate epitrochlear nodes, have the patient flex the elbow approximately 90 degrees. Feel for the nodes in the fossa approximately 3 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus, in the groove between the biceps and the triceps muscles as shown in Figure 12-16. Epitrochlear nodes are rarely palpable, but if they are present, their size, consistency, and tenderness should be described. Acute infections of the ulnar aspect of the forearm and hand may be responsible for epitrochlear adenopathy. Epitrochlear nodes are also observed in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Figure 12–16 Technique for evaluating epitrochlear nodes.

Other Special Techniques

All the special tests described here are to be used in conjunction with other forms of testing. Each of these vascular techniques is associated with many false-positive and false-negative findings. The results, therefore, must be considered as part of the total evaluation.

Evaluate Arterial Supply in the Lower Extremity

The most important sign of arterial insufficiency is a decreased pulse. In patients in whom chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremity is suspected, another test may be useful. The amount of pallor that develops after elevation and dependency of the ischemic extremity provides an approximate guide to the extent of decreased circulation. The elevation test is performed by having the patient lie on the back, and the examiner elevates the patient’s legs at approximately 60 degrees above the bed. The patient is asked to move the ankles to help drain the blood from the venous system, making the color changes more obvious. After approximately 60 seconds, the feet are inspected for pallor. Normally, no pallor is present (grade 0). Definite pallor in 60 seconds is grade 1, pallor in 30 to 60 seconds is grade 2, pallor in less than 30 seconds is grade 3, and pallor without elevation is grade 4. The patient is then asked to sit dangling the feet off the side of the bed, and the examiner assesses the time for color return (dependency test). Normally it takes 10 to 15 seconds for color to return and 15 seconds for the superficial veins to fill. If it takes 15 to 30 seconds for color return, moderate occlusive disease is present and indicative of adequate collaterals; if it takes more than 40 seconds for color to return, severe ischemia is present. A dusky or cyanotic color may also develop. This test is useful only if the valves of the superficial veins are competent. These tests are summarized in Table 12-3.

Table 12–3

Dependency Test for Arterial Insufficiency of the Lower Extremity

| Color Returns (seconds) | |

| Normal | 10–15 |

| Moderate ischemia | 15–30 |

| Severe ischemia | > 40 |

The ankle brachial index (ABI), or ankle brachial pressure index, is a quick noninvasive test and is the cornerstone of lower extremity vascular evaluation. It is the ratio of the blood pressure in the lower legs to the blood pressure in the arms. Compared with the arm, lower blood pressure in the leg is an indication of PVD. The ABI is calculated by dividing the systolic blood pressure at the ankle by the systolic blood pressures in the arm. The ABI test is a popular tool for the noninvasive assessment of PVD. Studies have shown the sensitivity of the test to be 90% with a corresponding 98% specificity for detecting hemodynamically significant stenosis of more than 50% in major leg arteries as defined by angiography.

Table 12-4 summarizes the most likely location of occlusive PVD based on the location of the patient’s pain.

Evaluate Capillary Refill Time in the Lower Extremity

Pressure on the arteriolar capillaries under the nail blanches or whitens the nail bed so that when the skin is uncompressed, the blood can flow back into the vessels and the nail bed returns to a normal color. Capillary refill time is the amount of time it takes for the skin to return to normal, usually 3 to 5 seconds.

The capillary refill time can be determined by compressing the toe tufts until they blanch. Prolongation of the time it takes for normal coloration to return after release is synonymous with arterial vascular insufficiency. The capillary refill test is best performed in a room-temperature environment. A cool environment can cause peripheral vasoconstriction and alter the results of the test. Dehydration, hypothermia, and most types of shock cause a prolonged capillary refill time in the absence of arterial insufficiency.

Evaluate Arterial Supply in the Upper Extremity

Chronic arterial insufficiency of the upper extremity is much less common than that of the lower extremity. The Allen test, which determines the patency of the radial and ulnar arteries, can be used to assess whether arterial insufficiency exists in the upper extremity. (The ulnar artery is normally not palpable.) This test takes advantage of the radial-ulnar loop. The examiner first occludes the radial artery by applying firm pressure over it. The patient is asked to clench the fist tightly. The patient is then asked to open the fist, and the color of the palm is observed. The test is repeated with occlusion of the ulnar artery. Pallor of the palm during compression of one artery indicates occlusion of the other.

Test for Incompetent Saphenous Veins

It is easy to demonstrate incompetent saphenous vein valves on examination. The patient is asked to stand, and the dilated varicose vein becomes obvious. The examiner compresses the proximal end of the varicose vein with one hand while placing his or her other hand approximately 15 to 20 cm below it at the distal end of the vein. When saphenous valves in the portion of the vein examined are incompetent, an impulse is transmitted to the examiner’s distal fingers.

Test for Retrograde Filling

The Trendelenburg maneuver is used to assess venous valvular competency in the communicating veins, as well as in the saphenous system. A tourniquet is placed around the patient’s upper thigh after it has been elevated 90 degrees for 15 to 20 seconds. The tourniquet occludes the great saphenous vein and should not occlude the arterial pulse. The patient is then instructed to stand while the examiner watches for venous filling. The saphenous vein should fill slowly from below in approximately 30 seconds as the femoral artery pushes blood through the capillary bed into the venous system. Rapid filling of the superficial veins from above indicates retrograde flow through incompetent valves of the communicating veins. After 30 seconds, the tourniquet is released. Any sudden additional filling also indicates incompetent valves of the saphenous vein.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

The signs of an acute arterial occlusion are the five Ps: pain, pallor, paresthesia, paralysis, and pulselessness.

Chronic progressive small-vessel disease is characteristic of diabetes mellitus. It is commonly observed that arterial pulses are present despite gangrene in the extremity. Figure 12-17 depicts dry gangrene of the toes in a diabetic patient.

Figure 12–17 Diabetic gangrene.

Diabetes has been associated with many skin disorders. The cutaneous hallmark of diabetes is a waxy, yellow or reddish-brown, sharply demarcated, plaquelike lesion known as necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. These lesions are classically found on the anterior surface of the lower legs. They are shiny and atrophic, with marked telangiectasia over their surface. The lesions have a tendency to ulcerate, and the ulcers, once present, heal very slowly. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum often predates the development of frank diabetes. The severity of the cutaneous lesion is not related to the severity of the diabetes. Figure 12-18 shows necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum; Figure 12-19 is a close-up photograph of the lesion in another patient with diabetes.

Deep vein thrombosis of a lower extremity is diagnosed when there is unilateral marked swelling, venous distention, erythema, pain, increased warmth, and tenderness. There is often resistance to dorsiflexion of the ankle. Calf swelling is present in most patients with femoral or popliteal venous involvement, whereas thigh swelling occurs with iliofemoral thrombosis. Figure 12-20 shows deep femoral vein thrombosis secondary to cancer. Notice the marked swelling of the left leg.

Figure 12–20 Deep vein thrombosis, left leg.

Gentle squeezing of the affected calf or slow dorsiflexion of the ankle may produce calf pain in approximately 50% of patients with femoral vein thrombosis. Pain elicited by this technique is referred to as Homans’ sign. Unfortunately, owing to the low sensitivity of Homans’ sign, this finding should not be used as a single criterion for diagnosing deep vein thrombophlebitis. A variety of unrelated conditions also may elicit a false-positive response.

Secondary to venous thrombosis, inflammation around the vein may result. Erythema, warmth, and fever then occur, and thrombophlebitis is present. In many cases, the examiner can palpate this tender, indurated vein in the groin or medial thigh. This is commonly referred to as a cord.

Deep vein thrombophlebitis is associated with symptomatic pulmonary embolism in approximately 10% of patients. If the embolus is large, main pulmonary artery obstruction may occur, which can result in death. It is estimated that an additional 45% of patients with thrombophlebitis have asymptomatic pulmonary emboli.

Several factors important in precipitating thromboembolism are outlined in Table 12-5.

Table 12–5

Precipitating Factors in Thromboembolism

| Factor | Cause |

| Stasis | Arrhythmia Heart failure Immobilization Obesity Varicose veins Dehydration |

| Blood vessel injury | Trauma Fracture |

| Increased coagulability | Neoplasm Oral contraceptives Pregnancy Polycythemia Previous thromboembolism |

An important and common peripheral vascular condition is Raynaud’s disease or phenomenon. Classically, this condition is associated with three color changes of the distal fingers or toes: white (pallor), blue (cyanosis), and red (rubor). These color changes are related to arteriospasm and decreased blood supply (pallor), increased peripheral extraction of oxygen (cyanosis), and return of blood supply (rubor). The patient may experience pain or numbness of the involved area as a result of the causes of pallor and cyanosis. During the hyperemic or rubor stage, the patient may complain of burning paresthesias. Between episodes, there may be no symptoms or signs of the condition.

Raynaud’s disease, which is primary or idiopathic, must be differentiated from Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is secondary. Table 12-6 lists some of the different characteristics of these conditions.

Table 12–6

Differential Diagnosis of Raynaud’s Disease and Raynaud’s Phenomenon

| Feature | Raynaud’s Disease | Raynaud’s Phenomenon |

| Sex | Female | Female |

| Bilaterality | Present (often symmetric) | ± (asymmetric) |

| Precipitated by cold | Common | Increases symptoms |

| Ischemic changes | Rare | Common |

| Gangrene | Rare | More common |

| Disease association* | No | Yes |

* Such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, or rheumatoid arthritis.

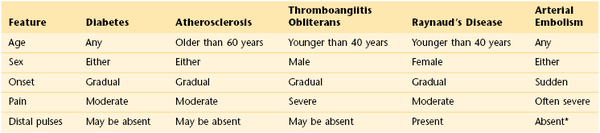

Gangrene is necrosis of the deep tissues resulting from a decreased blood supply. Features of the main vascular diseases causing gangrene of the lower extremities are summarized in Table 12-7.

Table 12–7

Differential Diagnosis of the Main Vascular Diseases Causing Gangrene

* Affected artery does not have pulsation.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Upchurch GR. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:584.

American Heart Association. Prevention and treatment of PAD. [Available at] http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/PeripheralArteryDisease/Prevention-and-Treatment-of-PAD_UCM_301308_Article.jsp [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Bloch MJ, Basile J. Clinical insights into the diagnosis and management of renovascular disease: an evidence-based review. Minerva Med. 2004;95:357.

Creager MA, Libby P. Peripheral arterial disease. Bonow RO, et al. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. ed 9. Saunders: Philadelphia; 2011.

Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW. Rutherford’s vascular surgery. ed 7. Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2010.

Decousus H, et al. Superficial venous thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism: a large, prospective epidemiologic study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:218.

Djurasovic M, et al. Contemporary management of symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(2):183.

Dworkin LD, Cooper CJ. Renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1972.

Goodacre S. In the clinic: deep vein thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:ITC3-1.

Hacklander T, et al. Evaluation of renovascular hypertension: comparison of functional MRI and contrast-enhanced MRA with a routinely performed renal scintigraphy and DSA. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:823.

Hirsch AT, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease); endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113(11):e463.

Khan NA, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295:536.

Lederle F. In the clinic: abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:ITC5-1.

Lederle FA, Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have abdominal aortic aneurysm? JAMA. 1999;281:77.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. What is peripheral artery disease? [Available at] http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/pad/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Rutherford RB, Krupski WC. Current status of open versus endovascular stent-graft repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:1129.

Suri P, et al. Does this older adult with lower extremity pain have the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis? JAMA. 2010;304:2628.

Tewari A, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152.

Turnbull JM. Is listening for abdominal bruits useful in the evaluation of hypertension? JAMA. 1995;274:1299.

Wilson J, Laine C, Goldman D. In the clinic: peripheral arterial disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:ITC3-1.

of calf—superficial femoral

of calf—superficial femoral of calf—popliteal

of calf—popliteal