The periodontal tissues and periodontal disease

Selection criteria

Several radiographic projections can be used to show the periodontal tissues. Those recommended by the Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK) in 2013 are summarized in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1

| Recommendation | Evidence-based Grading* |

| Horizontal bitewings if a patient has generalised pocketing <6 mm (BPE scores of Code 3) and little or no recession. | C |

| Vertical bitewings if a patient has pocketing 6 mm or more (BPE scores of Code 4), supplemented by paralleling technique periapicals at sites where the alveolar bone is not shown on the bitewings. | C |

| Bitewings (horizontal or vertical depending on pocket depth), supplemented by paralleling technique periapicals if necessary if a patient has localised pocketing | C |

| A paralleling technique periapical if a periodontal/endodontic lesion is suspected | C |

| CBCT is not indicated as a routine method of imaging prriodontal bone support | C |

| Small volume, high resolution CBCT may be indicated in selected cases of infra-bony defects and furcation lesions, where clinical and conventional radiographic examination do not provide the information needed for patient management | C |

*Evidence-based grading C = based on evidence from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experience of respected authorities and indicates an absence of directly applicable studies of good quality.

In addition, digital radiography and image manipulation including subtraction and densitometric image analysis (see Ch. 5), may assist in showing and measuring subtle changes in fine alveolar and crestal bone pattern. However, these techniques require the inclusion of a reference object of known density and a highly reproducible positioning technique to be helpful.

Important points to note

• In the interpretation of the periodontal tissues, images of excellent quality are essential – perhaps more so than in other dental specialties – because of the fine detail that is required.

• Exposure factors should be reduced when using film-based techniques to avoid burn-out of the interdental crestal bone.

Radiographic features of healthy periodontium

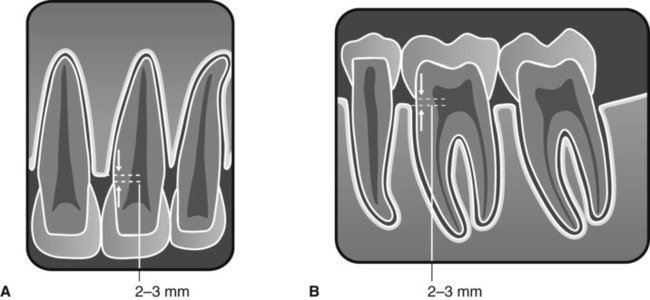

The usual radiographic features of healthy alveolar bone are shown in Figs 22.1 and 22.2 and include:

• Thin, smooth, evenly corticated margins to the interdental crestal bone in the posterior regions.

• Thin, even, pointed margins to the interdental crestal bone in the anterior regions.

• Cortication at the top of the crest is not always evident, owing mainly to the small amount of bone between the teeth anteriorly.

• The interdental crestal bone is continuous with the lamina dura of the adjacent teeth. The junction of the two forms a sharp angle.

• Thin even width to the mesial and distal periodontal ligament spaces.

Important points to note

• Although these are the usual features of a healthy periodontium, they are not always evident.

• Their absence from radiographs does not necessarily mean that periodontal disease is present.

• Failure to see these features may be due to:

• Following successful treatment, the periodontal tissues may appear healthy clinically, but radiographs may show evidence of earlier bone loss when the disease was active. Bone loss observed on radiographs is therefore not an indicator of the presence of inflammation.

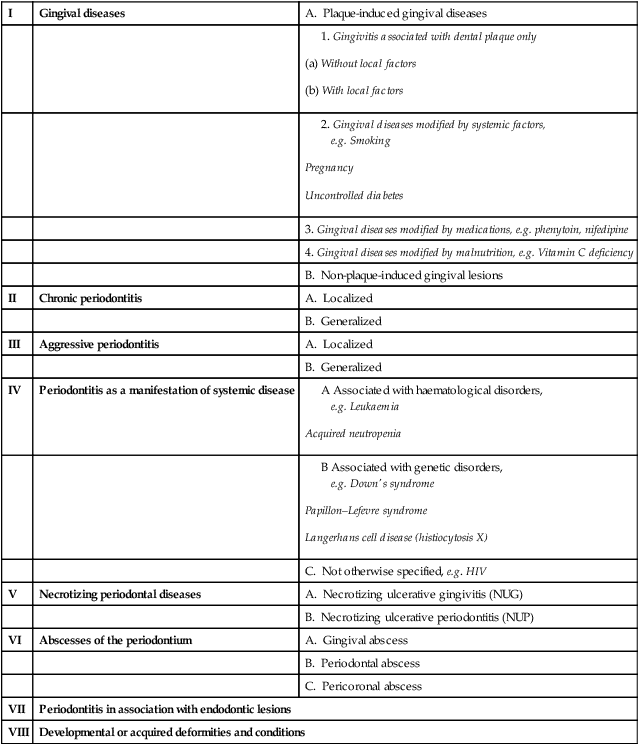

Classification of periodontal disease

Various classifications of periodontal disease have been put forward over the years. The most comprehensive, although not universally agreed, was produced by the International Workshop of the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology in 1999. A simplified version is shown in Table 22.2.

Table 22.2

| I | Gingival diseases | A. Plaque-induced gingival diseases |

Radiographic features of periodontal disease and the assessment of bone loss and furcation involvement

It is beyond the scope of this book to describe the features of all the periodontal diseases and conditions shown in the classification in Table 22.2. Discussion will be restricted to:

Periodontitis

Terminology

The terms used to describe the various appearances of bone destruction include:

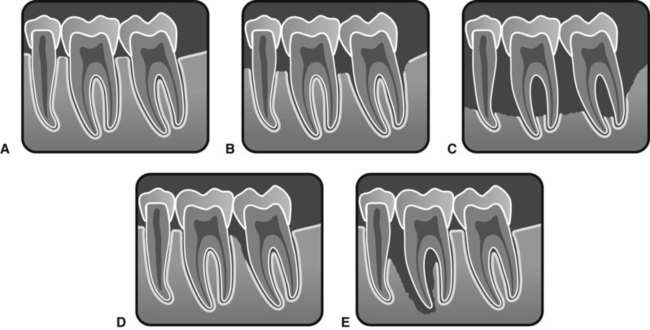

The terms horizontal and vertical have been used traditionally to describe the direction or pattern of bone loss using the line joining two adjacent teeth at their cemento–enamel junctions as a line of reference. The amount of bone loss is then assessed as mild, moderate or severe, as shown diagrammatically in Fig. 22.3.

Severe vertical bone loss, extending from the alveolar crest and involving the tooth apex, in which necrosis of pulp tissue is also believed to be a contributory factor, is classified as periodontitis associated with an endodontic lesion, often abbreviated to a perio-endo lesion (see Figs 22.3E and 22.14).

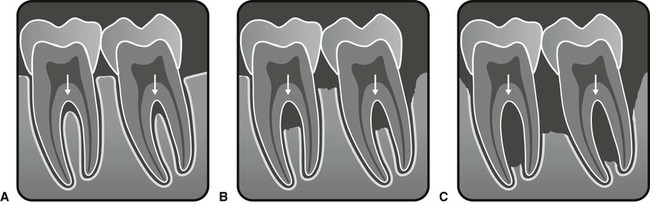

The term furcation involvement describes the radiographic appearance of bone loss in the furcation area of the roots which is evidence of advanced disease in this zone, as shown diagrammatically in Fig. 22.4. Although central furcation involvements are seen more readily in mandibular molars, they can also be seen in maxillary molars despite the superimposed shadow of the overlying palatal root. In addition, early maxillary molar furcation involvement between the mesiobuccal or distobuccal roots and the palatal root produces a characteristic triangular-shaped radiolucency at the edge of the tooth (see Figs 22.8C and 22.10A).

Chronic periodontitis (Figs 22.5–22.11)

• Inflammation (usually a progression from chronic gingivitis)

• Destruction of periodontal ligament fibers

• Resorption of the alveolar bone

• Loss of epithelial attachment

It is the resorption of the alveolar bone that provides the main radiographic features of chronic periodontitis. These include:

• Loss of the corticated interdental crestal margin, the bone edge becomes irregular or blunted

• Widening of the periodontal ligament space at the crestal margin

• Loss of the normally sharp angle between the crestal bone and the lamina dura – the bone angle becomes rounded and irregular

• Localized or generalized loss of the alveolar supporting bone

• Patterns of bone loss – horizontal and/or vertical – resulting in an even loss of bone or the formation of complex intra-bony defects

• Loss of bone in the furcation areas of multirooted teeth – this can vary from widening of the furcation periodontal ligament to large zones of bone destruction

• Widening of the interdental periodontal ligament spaces

• Associated complicating secondary local factors – although the primary cause of periodontal disease is bacterial plaque, many complicating secondary local factors may also be involved. Some of these factors can be detected on radiographs (see Fig. 22.11) and include:

Abscesses of the periodontium

As was shown in the classification in Table 22.1, abscesses of the periodontium are divided into three groups. These include:

Typically the patient presents with a localized acute exacerbation of underlying periodontal disease, usually originating in a deep soft tissue pocket that may have become occluded. The diagnosis of an abscess is made clinically where the signs of acute inflammation and infection are evident. Vitality testing helps to differentiate between the lateral periodontal abscess and the perio-endo lesion. The underlying radiographic bone changes may be indistinguishable from other forms of periodontal bone destruction, as shown in Fig. 22.14.

Evaluation of treatment measures

The success or otherwise of these treatment measures can be assessed by a combination of clinical examination, including probing and attachment loss measurements, and periodic radiographic investigation, as shown in Figs 22.15 and 22.16. Note: To provide useful information sequential radiographs ideally should be comparable in both technique and exposure factors.

Limitations of radiographic diagnosis

• Superimposition and a two-dimensional image bringing about the following problems:

– It is difficult to differentiate between the buccal and lingual crestal bone levels

– Only part of a complex bony defect is shown

– One wall of a bone defect may obscure the rest of the defect

– Dense tooth or restoration shadows may obscure buccal or lingual bone defects, and buccal or lingual calculus deposits

– Bone resorption in the furcation area may be obscured by an overlying root or bone shadow.

• Information is provided only on the hard tissues of the periodontium, since the soft tissue gingival defects are not normally detectable.

• Bone loss is detectable only when sufficient calcified tissue has been resorbed to alter the attenuation of the X-ray beam. As a result, the histological front of the disease process cannot be determined by the radiographic appearance.

• Technique variations in image receptor and X-ray beam positions can considerably affect the appearance of the periodontal tissues; hence the need for accurate, reproducible techniques as described in Chapter 10.

• Exposure factors can have a marked effect on the apparent crestal bone height – overexposure causing burn-out when using film-based imaging.

• Complete reliance cannot be placed on the inherently inferior images of panoramic radiographs although they do provide a reasonable overview of the periodontal status (see Fig. 22.17 and Ch. 15).

• Some of the limitations of two-dimensional conventional radiography, in visualizing three-dimensional periodontal bone defects, can be overcome by high resolution cone beam CT (see Ch. 16).

To access the self assessment questions for this chapter please go to www.whaitesessentialsdentalradiography.com

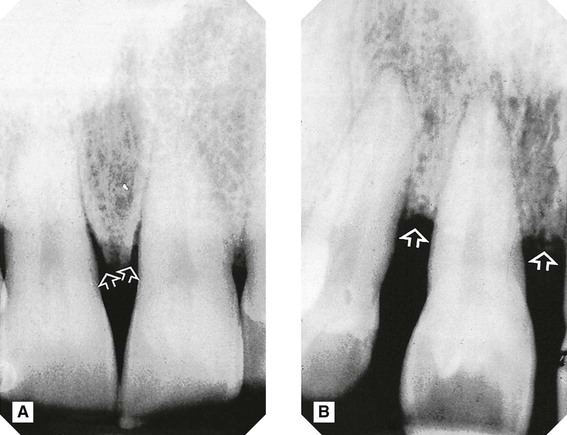

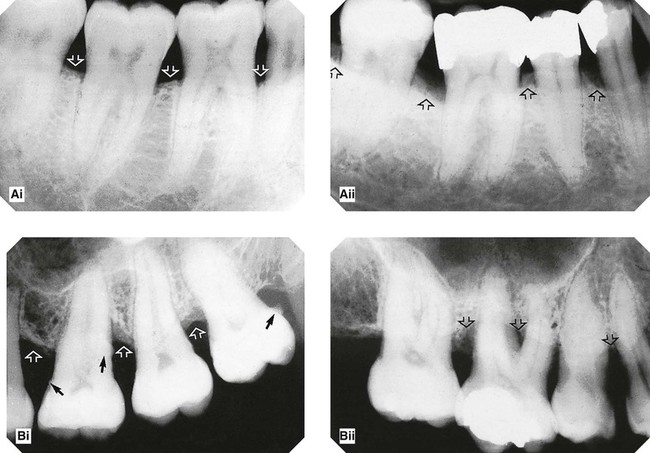

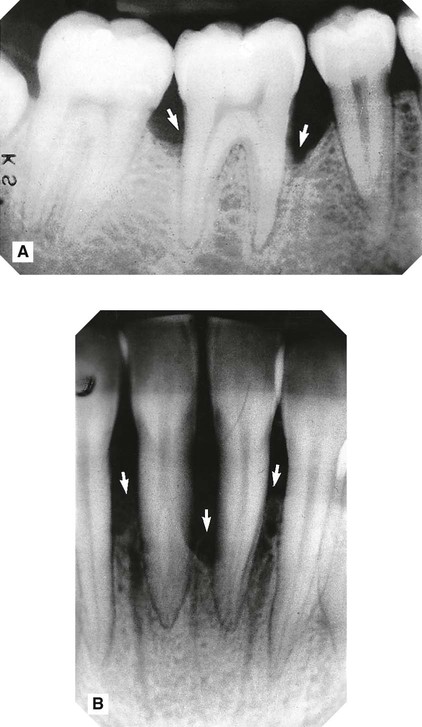

(slightly reduced exposure) showing the radiographic features of a healthy periodontium (arrowed).

(slightly reduced exposure) showing the radiographic features of a healthy periodontium (arrowed).

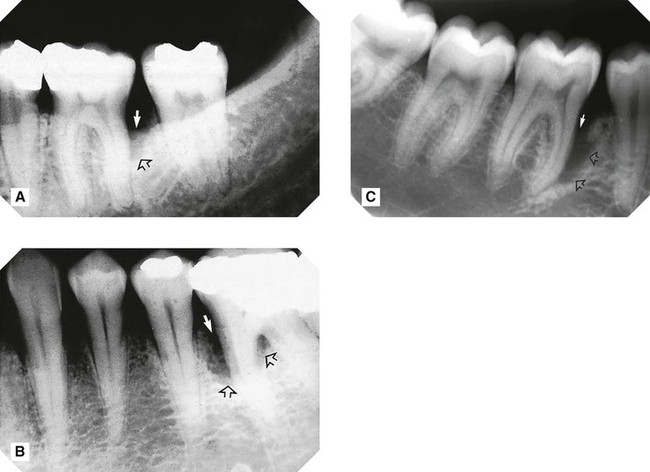

. E Extensive localized bone loss involving the apex of

. E Extensive localized bone loss involving the apex of  – the so-called perio-endo lesion.

– the so-called perio-endo lesion.

– a so-called perio-endo lesion. The patient had presented clinically with a periodontal abscess.

– a so-called perio-endo lesion. The patient had presented clinically with a periodontal abscess.

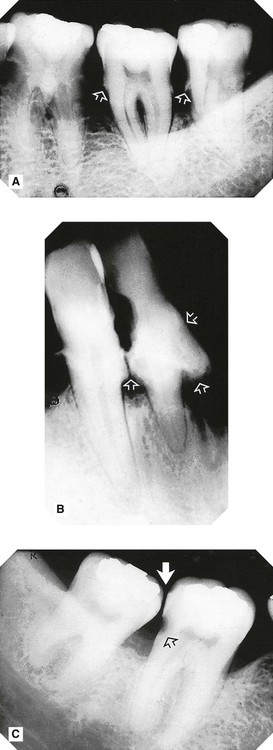

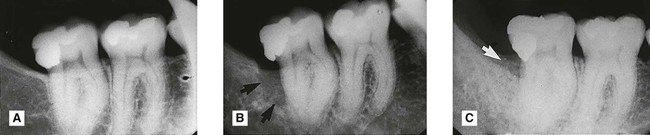

(arrowed). C Follow-up film 3 years later following guided tissue regeneration showing the reduced defect (arrowed) and the bone in-fill.

(arrowed). C Follow-up film 3 years later following guided tissue regeneration showing the reduced defect (arrowed) and the bone in-fill.

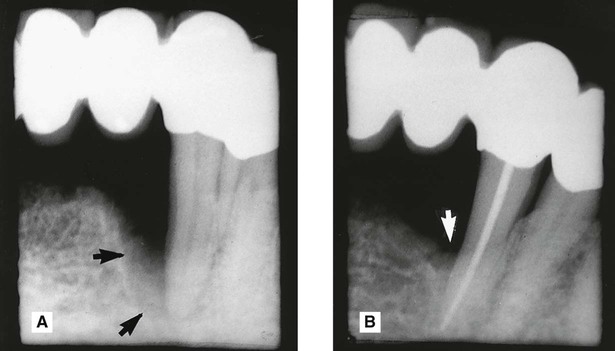

with severe bony defect on the mesial aspect of the root (arrowed). B Follow-up film 2 years later following successful endodontic therapy and guided tissue regeneration. Note the reduced bony defect (arrowed).

with severe bony defect on the mesial aspect of the root (arrowed). B Follow-up film 2 years later following successful endodontic therapy and guided tissue regeneration. Note the reduced bony defect (arrowed).

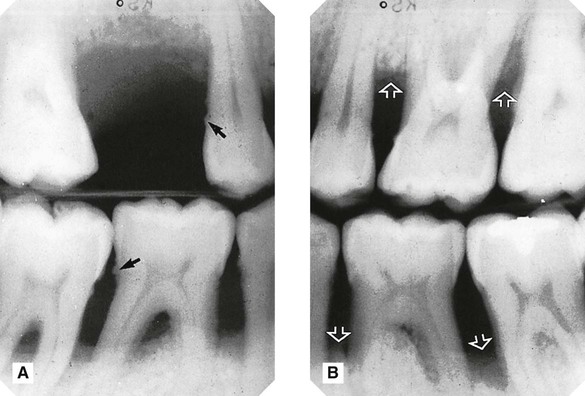

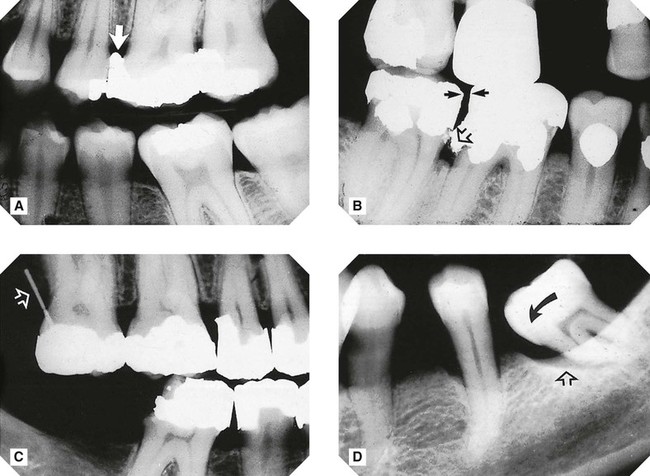

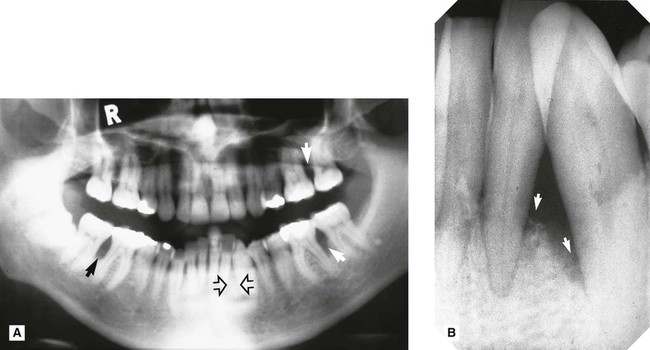

region (open arrows) owing to superimposition of the radiopaque artefactual shadow of the cervical vertebrae. B Periapical of

region (open arrows) owing to superimposition of the radiopaque artefactual shadow of the cervical vertebrae. B Periapical of  region taken at the same time showing the severe bony defect (arrowed) that was actually present.

region taken at the same time showing the severe bony defect (arrowed) that was actually present.